Published on Nov 4th, 2024

1988: Benjamin Britten’s Albert Herring in a modern setting

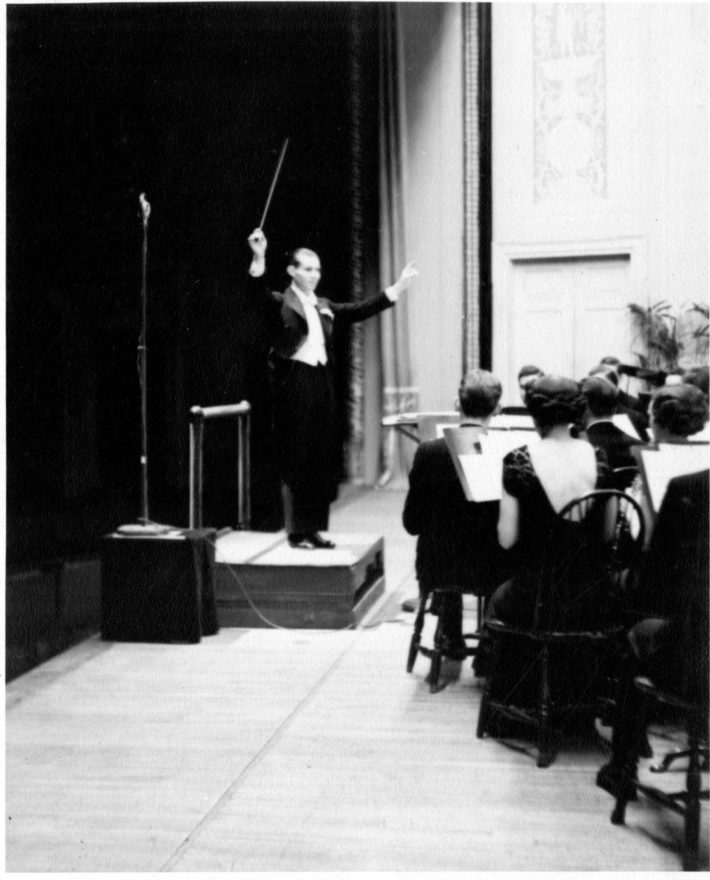

Thirty-six years ago this week, on November 4-6, 1988, Eastman Opera Theater staged Benjamin Britten’s Albert Herring in Kilbourn Hall, marking the fourth Eastman production of that opera.[1] Directed by Richard Pearlman and conducted by David Effron, the production was double-cast for four performances. A chamber opera in three acts with libretto by Eric Crozier (1914-1994), Albert Herring was the fourth of Britten’s seventeen operas. Britten (1913-1976) wrote Albert Herring, his only truly comic opera, for the newly formed English Opera Group, which gave the premiere at Glyndebourne on June 20th, 1947 with the composer conducting. The opera was dedicated to novelist E. M. Forster (1879-1970), with whom Britten would maintain a growing association over the ensuing years. With its vast comic appeal and its numerically finite forces (13 singing roles and a 13-piece orchestra), Albert Herring quickly became a staple in the repertory; in particular, it forms a convenient and accessible vehicle for university and collegiate forces. Librettist Crozier based the libretto on the short story Le Rosier de Madame Husson (1888) by French novelist and poet Guy de Maupassant (1850-1893), transferring the story’s setting from provincial France to an East Anglian village around 1900. The printed program (displayed here) contains both the synopsis written by Mr. Crozier for the premiere and Mr. Pearlman’s Director’s Notes.

For purposes of this account, Albert Herring is set in the fictional town of Loxford, where the action evolves around young Albert, who works in his mother’s greengrocer’s shop. So thoroughly the widowed Mrs. Herring rule young Albert’s life that he essentially has no life. When the village’s autocratic noblewoman, Lady Billows, casts about for an eligible young woman to be crowned Queen of the May (or the May Queen), every potential candidate is deemed morally wanting. By way of a pragmatic solution, a May King will be crowned, and the well-behaved (if mousy and beleaguered) Albert Herring is selected for the honor. Come May Day, Albert receives the honor with little manifest enthusiasm, and following his coronation, he disappears for a night of debauchery, stimulated by the spiked lemonade he has drunk (thanks, Sid!). On returning the following morning, Albert faces a chorus of disapproval—none of which matters to him, for he is now richer in experience and has learned the value of his independence. Writing in his Director’s Notes, Mr. Pearlman commented on the opera’s “wry view of human nature and the hypocrisy and claustrophobia of small town life” that in Albert Herring are “so well observed as to be universal and timeless.” Several paradigms can apply here: a conflict of the young vs. the aged, the new vs. the time-honored (but potentially outmoded), and the tensions that arise when the interests of the individual clash with those of the surrounding collective. Indeed, the latter was a central concern in several of Britten’s operas.

The 1988 production was unusual for EOT in that it was set contemporaneously. Director Pearlman never hesitated to re-imagine operas according to his well-founded artistic convictions, but the contemporaneous setting represented something unique in EOT’s experience. Mr. Pearlman saw in Albert Herring “humor and darker implications” that rendered it ideal for updating—in this instance, transferred from 1900 to 1988, or as Mr. Pearlman noted, “the land of Monty Python, Margaret Thatcher, Sid and Nancy, and other manifestations of late century ‘Angloangst’.”[2] These references are now becoming dated, but they were all highly relevant in 1988. Monty Python, an icon of raw, edgy British humor that was known to the American audience through syndication of the television program Monty Python’s Flying Cirus. Mrs. Thatcher, Prime Minister from 1979 until 1990, a thoroughly polarizing and divisive figure whom one either loved or hated, and under whom the divide between rich and poor was growing ever wider, much as it was doing under President Reagan.[3] Sid and Nancy—conveniently the names of two supporting characters in Albert Herring—was a recently released motion picture depicting the relationship of punk performer Sid Vicious and his girlfriend Nancy Spungen.[4] Moreover, notwithstanding the wealth newly enjoyed by the corporate class at the top of the social ladder, Britain in 1988 was not entirely a glorious realm, what with tensions over the nation’s relationship with Europe (Mrs. Thatcher herself was, quite famously, a Eurosceptic, and it would ultimately bring down her government), a population not entirely at peace with the nation’s diminished post-Imperial status in the post-War world (post-World War II, that is), social tensions amidst the fitful adjustment to a multi-racial society, and the grit and grime of life during the economic crisis of the 1970s still a recent memory. An “untidy National Attic,” as Mr. Pearlman summed up in his Director’s Notes.

To set the stage (literally) for the EOT production, Mr. Pearlman engaged the services of Jeffrey McDonald, a set designer based in New York City, who brought to bear a lively concept. Documents in the Richard Pearlman Collection at the Sibley Music Library confirm the depth of research and the trenchant creativity that informed the production. In particular, the plans for costume design and set design all bear out the concept and execution. Designer McDonald was aiming, with insistent deliberation, for a clearing of “the untidy National Attic” such as Mr. Pearlman would later allude to in his Director’s Notes. In a memo to Mr. Pearlman, Mr. McDonald described the stage as being “. . . packed with assorted English imperialistic paraphernalia & junk (the patrimony, so to speak) . . . the scrim is painted with a great British allegorical painting representing the Empire . . . . Throughout the entire piece the hoard will be gradually removed & carted offstage by workmen until by the end of the opera, nothing is left but a terrazzo floor and the clutter left behind when the orchestra leaves.” Regrettably, no video footage of this production is known to be extant today, and the production photographs are focused so closely on the singers as to reveal not much of the surrounding sets and scrim painting. Nevertheless, that the production proceeded from this way of thinking is itself informing. The printed program hinted at the contemporary setting with its drawings of both Mrs. Thatcher and Nancy in her party guise. The photographs displayed here, which capture members of the second cast in a handful of the opera’s main events, confirm the concept’s execution. I should add that an online survey of the careers of these EOT performers confirms how far these performers have travelled professionally. Bravi to them all!

The EOT production was covered in the Rochester press, for better or for worse; one feature article and two reviews are displayed here. For reasons entirely their own, the local writers chose to play up what they perceived as the production’s “punk” aspect, and to an unreasonable and frankly ridiculous degree. Perhaps the Rochester Democrat & Chronicle feature article, with its photo of Designer McDonald on the front page, brought in larger audience numbers from the off-campus community. In any event, what happened next followed directly from the local hype. Eastman ran afoul of the licensing body (Boosey & Hawkes, who were Britten’s publisher) when an unnamed source sent at least one of the local reviews to Boosey’s offices in New York City. The reaction at Boosey prompted a letter to Eastman School Director Dr. Robert Freeman, succinctly forbidding any further performances of the EOT production:

“We are surprised and disappointed that we were not advised in advance of the time frame changes planned for your production. While the reviewer seems most impressed it is doubtful that Mr. Britten would have approved. Certainly the Executors of his Estate do not, nor do we.

“We write therefore to advise there should be no further performances of this production.”

Boosey gave no indication of having investigated the matter other than having read the provided review. In other words, the company’s decision was based on hearsay—on a hyped-up review written by a local writer who had unreasonably emphasized “punk”—and without seeing fit to give the Eastman School of Music the benefit of the doubt.. Eastman’s reply was substantive. In a letter (December 19, 1988) to Boosey, Dr. Freeman set the record straight with respect to the intentions behind the EOT production. Having both seen and admired the EOT production “both as Eastman director and as an operatic historian,” he faulted Boosey for apparently having jumped to a conclusion (“. . .without further investigation, you appear to have accepted as gospel the headline of a local review”). He elaborated:

“Of the thirteen characters in the piece, only two are in fact presented in a manner which anyone could possibly describe as ‘punk.’ In Richard Pearlman’s interpretation of the opera in contemporary England, what he did with the work was infinitely less radical than what Mr. Crozier, the librettist, did in adapting the original Maupassant story.

“The real issue here is the same as with the performance of any work: was the intent and execution a frivolous exploitation of the material or was it a serious attempt to serve the composer at the work’s deepest level? You apparently assume the former to be true. The production was, to the contrary, a tribute to Benjamin Britten’s life-long commitment to the issues of individual freedom and social justice, and how they are inextricably linked. The point is that the ideals Mr Britten spent his life extolling are alive and well in contemporary England, though they still need defending against the same dragons. Indeed, it seems to me that your letter is in itself an embodiment of the neophobia made sport of in the work itself.

“How well Mr. Britten’s intentions were carried out is not, of course, for us to say. However, it is relevant in this content that Richard Pearlman has directed the works of such contemporary composers as Samuel Barber, Lee Hoiby, Iain Hamilton, and George Rochberg to their great satisfaction. A year ago, Leopold Godowsky III, as the representative of the Gershwin estate, was thrilled with what Richard Pearlman accomplished with the Gershwin material that lay at the basis of our production of Reaching for the Moon.”[5]

Dr. Freeman enclosed three items in support of his letter: a copy of Mr. Pearlman’s Director’s Notes for the EOT production; a copy of a New York Times review of a production of Britten’s Turn of the Screw that Mr. Pearlman had directed;[6] and a copy of an article by Pulitzer Prize-winning music critic Martin Bernheimer that praised Mr. Pearlman’s work. He closed his letter cordially with his hope that the communication would continue. Happily, Eastman’s working relationship with Boosey was not irreparably ruptured by this matter, for since that time, Eastman Opera Theater has been granted license to produce Albert Herring twice more (in 1998 and 2014).

Both casts of the 1988 production were recorded on tape and can be enjoyed via the Eastman Audio Archive. The Richard Pearlman Collection offers substantive documentation of this production, including numerous photographs; indeed, this is the most substantively documented of any of the six Eastman productions of Albert Herring. This marked one more noteworthy production in the Eastman School’s rich operatic history of Eastman Opera Theater, which under directors Leonard Treash and Richard Pearlman had firmly established itself as a vehicle for high-level performance and artistry.

[1] To date, there have been six Eastman productions altogether: March, 1966 (Leonard Treash, director; László Halász, conductor); February-March, 1975 (Leonard Treash, director; Robert Spillman, conductor); March, 1979 (Edward Berkeley, director; Robert Spillman, conductor); November, 1988 (Richard Pearlman, director; David Effron, conductor); November, 1998 (Steven Daigle, director; John Greer, conductor); and, November, 2014 (Stephen Carr, director; Benton Hess, conductor). All six productions have been in Kilbourn Hall.

[2] This word was not coined by Mr. Pearlman. I haven’t gone back into 1980s literature to discern its usage, but I’d note here that it has been used in recent years in Eastern Canada to describe the viewpoint felt by some among the Anglophone population of Québec.

[3] Indeed, Mrs. Thatcher and Mr. Reagan had become fast friends after Mr. Reagan took office, and their friendship lent an added wrinkle to the UK/USA “special relationship” in those years. The special relationship has waxed and waned depending on who’s in office at any given time, but it was alive and well in the ‘80s.

[4] Left out of this late 1980s mix was the specter of AIDS, which for Mr. Pearlman as a gay man would no doubt have been a huge concern, but the case could be made that HIV might not yet have touched any lives in a small, rural backwater like Loxford.

[5] The 1987 production of Reaching for the Moon was promoted as the world premiere of a “new Gershwin musical” in that it presented for the first time in a staged production original material that George and Ira Gershwin had shelved.

[6] Significantly, Dr. Freeman commented that Mr. Pearlman himself had judged that production as “considerably more unorthodox than Eastman’s production of Albert Herring, and was judged by many to be one of the most successful presentations of this work ever done in the United States.”