Published on Oct 7th, 2024

2003: National Coming Out Day at Eastman

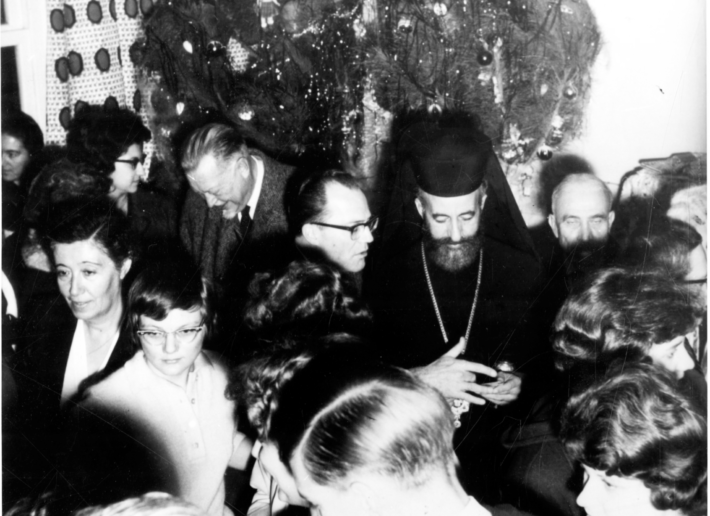

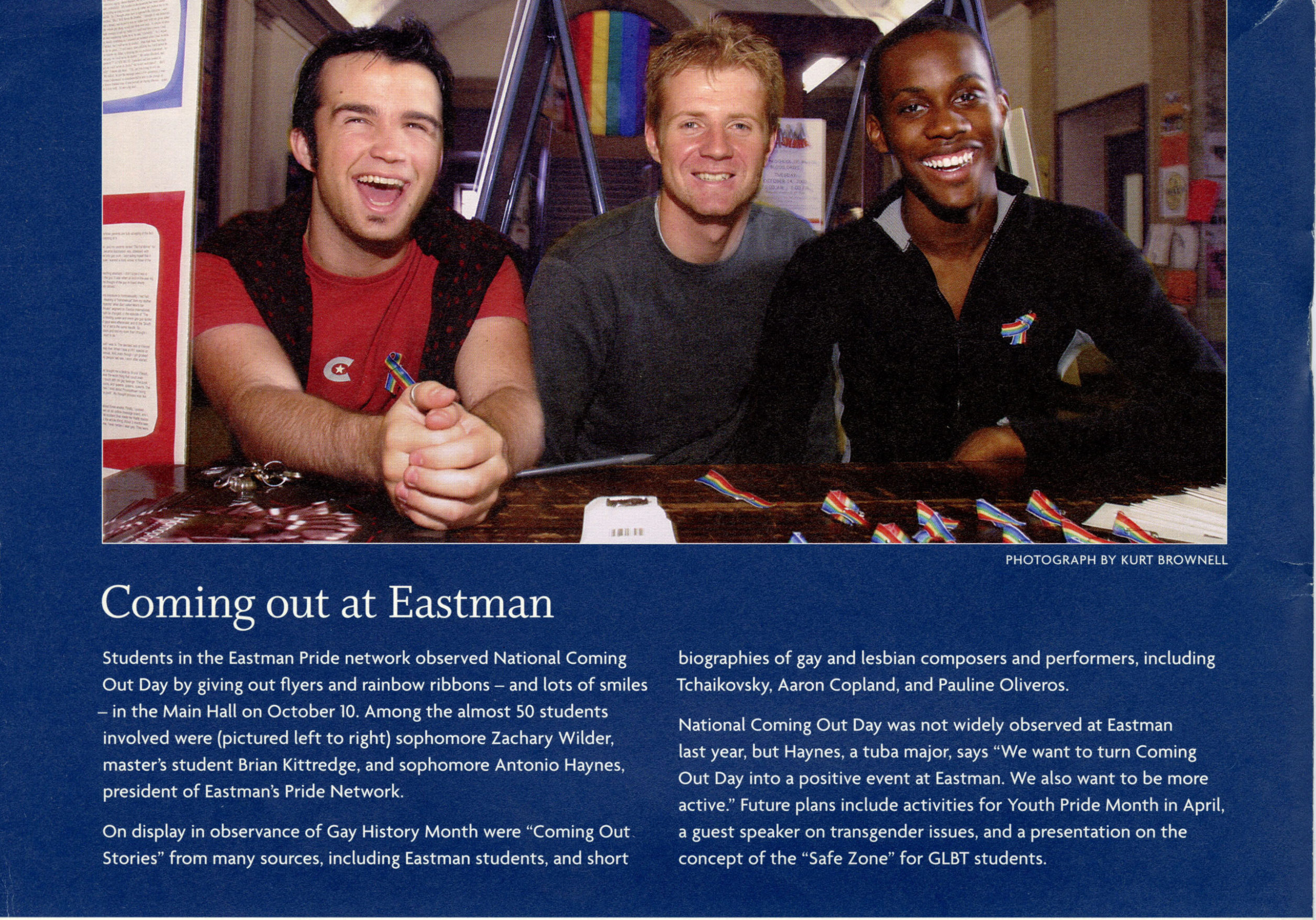

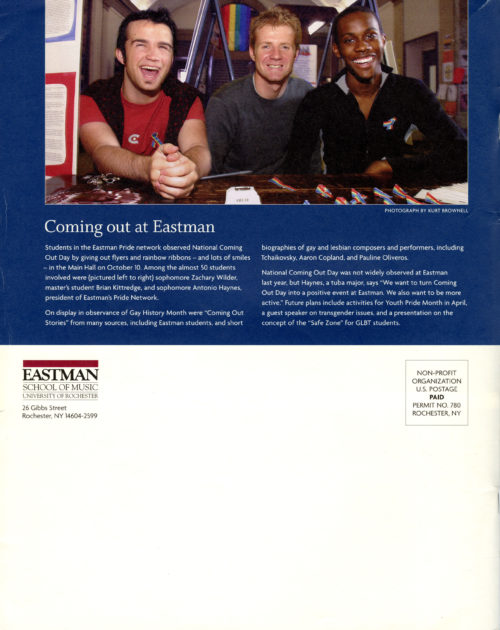

Twenty-one years ago this week, on Friday, October 10th, 2003, National Coming Out Day was observed at the Eastman School OF Music, planned and coordinated by the Eastman Pride Network, a student affinity group of LGB students.[1] Approximately 50 students were involved in the organization and execution, which included the distribution of flyers and rainbow ribbons at a station in the main hall (today Lowry Hall). In addition, a display of Coming Out Stories had been created, featuring the stories of Eastman students alongside those of well-known individuals. While this may or may not have been the first-ever National Coming Out Day observance at Eastman, suffice it to say that October 10th, 2003 remains singularly noteworthy in that it received prominent attention in the pages of Eastman Notes, promoted with no less than a color photograph on one of the covers. In that photo, three students beamed into the camera with manifest joy on their faces; they were Zachary Wilder (later BM ‘06E), Brian Kittredge (later MM ‘04E), and Antonio Haynes (later BA ‘07), who was then serving as the President of the Eastman Pride Network. This feature and photograph marked the first-ever LGBTQ-concerned news to have been published in Eastman Notes.[2] With this publicity the Eastman School was unmistakably serving notice that a safe, supportive, and friendly environment was a priority at the downtown campus.

► Eastman Notes, vol. 22, no. 1, December, 2003. Front and back covers.

Arriving at the year 2003, the history of National Coming Out Day had not been long. At the behest of two professionals—psychologist Robert Eichberg[3], and activist-political leader Jean O’Leary[4]—National Coming Out Day was inaugurated to serve as a vehicle for openness and positivity. The 1988 observance was timed with the first anniversary of the Second National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. The first National March had taken place in 1979, ten years after the Stonewall uprising that had marked the birth of gay liberation in the United States; by 1979 the gay and lesbian community had won only a slight string of political and legislative victories nationally. The Second National March (1987) numbered no fewer than 750,000 participants, and was informed by the urgency, desolation, heartbreak, and outrage that had reached a boiling point after the deaths of thousands from AIDS in the face of a de facto refusal by the Federal Government to involve itself in any substantive way to combat HIV.[5] National Coming Out Day was thus launched in a spirit of urgency and fervor to rally the LGB community and to heighten visibility. An annual event since 1988, National Coming Out Day is observed by individuals and organizations alike; it is widely covered in the broadcast and print media and on social media. Its fundamental premise is that individuals will openly acknowledge themselves as LGBTQ people in a spirit of positivity. The advantages of coming out, both for the individuals concerned and for society at large, have been well documented.

Today, LGBTQ students at the Eastman School are represented by the Eastman Queer Alliance (EQ), established in the fall of 2022. EQ was profiled by Anna Reguero (Office of Communications) on the ESM website on the occasion of Pride earlier this year. EQ’s current President is Freddie Kartoz; the faculty advisors are Alison d’Amato and Jean Pedersen. As Freddie Kartoz shared with me, Eastman’s first openly trans student enrolled here two years before Freddie’s own enrollment; since then, trans students have increased in number and visibility at Eastman. Thus, what had been in an earlier time a solely LGB focus has broadened to affirm an all-inclusive LGBTQ vision, embracing trans students and supporting them in living their lives openly. Moreover, one core aspect of EQ’s mission is to ensure that Pride will remain active and relevant on a year-round basis. EQ succeeds the group Spectrum which was discontinued in 2020 during the pandemic. Spectrum had, in turn, been preceded by the Eastman Pride Network, whose details I don’t happen to know at this time. The history of LGBTQ student involvement at Eastman has yet to be written, and in the service of the Eastman School of Music Archives, I would very much like to hear from Eastman alumni, students, and faculty members who might have information to share.

In the context of Eastman students observing National Coming Out Day in 2003, and with the milestone that was inherent in Eastman’s promotion of same, it is fitting to acknowledge that the year 2003 had already seen one other gesture that we might now regard as a step in the Eastman School’s journey towards full diversity, equity, and inclusion. Five months earlier, at Commencement on Sunday, May 18th, 2003, the invited Commencement speaker had publicly spoken of the expulsion of an Eastman student for being gay—the first acknowledgement on record of a gay student’s expulsion from Eastman. Since my own arrival at Eastman in 1999, I had heard, on several occasions, oral transmission of rumors and suppositions regarding the ill treatment of gay students in earlier decades, suggesting a dark chapter in the school’s past that had gone undocumented. Now, in 2003, Charles Strouse, BM ‘47E, having personal knowledge on the subject, invoked the expulsion of his friend and classmate William Flanagan. Speaking at Commencement, Mr. Strouse (b. 1928), composer of several Broadway musicals, shared some details of his Eastman years and warmly recounted his friendships with two classmates, the first of whom was Jim Brown, about whom Mr. Strouse told a charming anecdote.[6] He continued:

And then there was another friend, and why shouldn’t I take this time to mention his name? He was my closest friend at Eastman, a fine creative mind, and the first person who said to me I was a good composer. How could I ever forget that? His name was William Flanagan, and he was expelled from Eastman for being gay. It’s a mark of how far we’ve come that I can say that.[7]

I was in the audience that day, and in the moment, I was riveted to my seat by Mr. Strouse’s words. Someone with personal knowledge on the subject was finally speaking out. Moreover, given the morés of U.S. society in pre-Stonewall years and also the arch-conservatism of ESM Director Howard Hanson, it is not difficult to surmise the expulsions of other gay students besides the late Mr. Flanagan. Mr. Strouse’s Commencement address was later published in its entirety in Eastman Notes, but it is worthwhile to listen to the recording, which captures his measured tone, laden with respect at the mention of his friend. Mr. Strouse did not happen to elaborate on Mr. Flanagan that day, and I care to do so here.

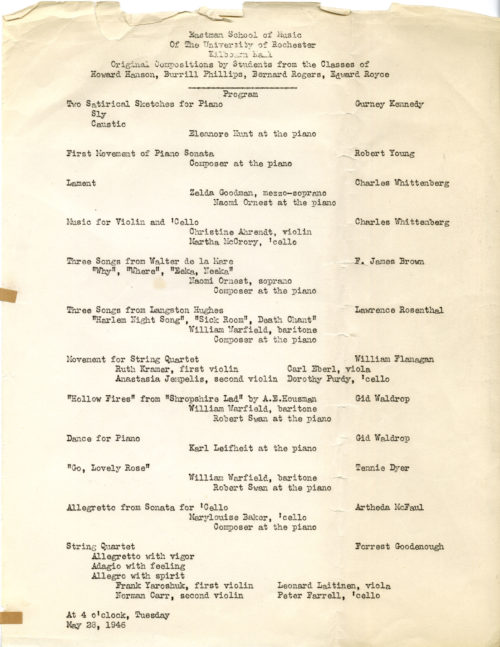

William Flanagan, born in Detroit in 1923, entered the annals of 20th-century American music as both composer and writer. As with many an Eastman student in the school’s early decades, his footprint at the Eastman School is restricted to a handful of documents. His transcript confirms that he was enrolled for three years—from September, 1943 until June, 1946, as confirmed by the Office of the Registrar—and it ends with a succinct comment indicating “recommended to discontinue” by the administrative committee in June, 1946.[8] We see Mr. Flanagan in the yearbooks of 1944, 1945, and 1946 (displayed here); in an earlier time, the Eastman School published yearbook photographic representation of all students, not restricting the class photos to the senior class. Further, the printed programs of recitals of original compositions by composition majors in 1945 and 1946 (displayed here) cite works by him, both of which instrumental works. He would soon embrace vocal music, which would prove to be his natural medium. From the late 1940s onwards, his career trajectory was reasonably straightforward, if not in fact happy on a personal level. Mr. Flanagan spent two summers at Tanglewood, studying first with Arthur Honegger and then with Aaron Copland, who was a huge influence on him. Afterwards, he studied for two years with David Diamond[9] in New York City, where he took up residence and would remain permanently. Turning to writing as a professional source of income, Mr. Flanagan became a respected reviewer, essayist, and critic, writing for such journals as Musical America, New York Herald Tribune, and ultimately Stereo Review, where he was employed at the time of his death.[10] In addition, he wrote highly literary jacket notes for many LP sound recordings. He is profiled in several reference sources, including a biographical article by his friend Ned Rorem in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, now appearing digitally in Oxford Music Online[11]. Sadly, his discography today is not extensive; several analog-era CRI (Composer Recordings, Inc.) recordings of his music are now out of print. (Note that the Sibley Music Library holds copies of same in its recordings stacks.) Nevertheless, today on YouTube one can access the commercial recording of his orchestral work A Concert Ode by the Detroit Symphony Orchestra (which premiered the work); live performances of his gorgeously lyrical Chaconne for violin and piano, and the song “Valentine for Sherwood Anderson” with text by Gertrude Stein; and the CRI recording of his vocal chamber work “Another August”. In addition, for those readers who are in the UR network, the Naxos Music Library offers access to recordings of the songs “Valentine for Sherwood Anderson” and “Horror Show”. (The latter might well have been influenced by Mr. Flanagan’s boyhood experience of music in films, an aspect of his musical upbringing noted by his sometime romantic partner and occasional artistic collaborator Edward Albee.[12]) In the realm of vocal music, Mr. Flanagan also composed two operas with librettos by Mr. Albee (the second opera was not completed).

Following his invited appearance at Eastman’s Commencement, Charles Strouse later recounted his friendship with Mr. Flanagan in his autobiography (2008). Admitted to Eastman at the tender age of 15, the young Strouse was beset by tremendous insecurity and social isolation as a new freshman. Although he was straight, he took up socially “. . . with a new circle of male friends who seemed to understand my feelings. They were all homosexual in a 1940s world that considered their lifestyle to be illicit, immoral, and unpatriotic.” (Illicit, immoral, unpatriotic: today, in 2024, we continue to hear those same words, relentlessly pushed by some on the political and religious right.) Mr. Strouse recalled Mr. Flanagan as one of the leaders of that circle, describing him as “tall, cynical, sallow (he always drank), Irish Catholic, brilliant . . . .” (The emphasis is Mr. Strouse’s own.) As time passed, Mr. Flanagan did, indeed, become Mr. Strouse’s closest friend at Eastman, just as Strouse had shared at Commencement. “I used to trail him around, copying his moves, his attitudes. We all did.” Strouse frequently took refuge in Flanagan’s dorm room for company and looked to him for encouragement in his composing. In general, he “idolized” older student. Interestingly, Strouse doesn’t mention Flanagan’s expulsion in the book,[13] but instead, segues from the Eastman years to having social and professional contact with Flanagan in New York City in the later 1940s. Strouse later describes Flanagan’s decline after the break-up of his relationship with playwright Edward Albee (1928-2016), a period when Flanagan was “drinking more and more . . . . I wanted to be there for him, and often invited Bill over for dinner, but I was now married with children , and it was hard to be that support he needed.” Strouse’s grief after Flanagan’s untimely death in 1969 is especially acute, asking himself , “. . . was I truly a friend to him? Could I have helped save him? The guilt eats at me even now.”[14] Poignant words.

Another composer who counted William Flanagan as a close friend was Ned Rorem (1923-2022), who maintained daily contact with Mr. Flanagan over the course of several years. The two men shared several commonalities: both were dedicated composers of song; both adored the music of Ravel and both nursed an affinity for the French (as opposed to the German) aesthetic; and as composers, both were proponents of a basic tonality in their respective compositions. Mr. Rorem amply recounted their professional, social, and personal rapport in his diaries and essays. In particular, these lines from a 1987 diary entry, written with Mr. Rorem’s characteristic candor and occasional irreverence, capture much of Mr. Rorem’s regard for Mr. Flanagan and for his art:

Bill Flanagan was my best friend among composers. From our first encounter in the autumn of 1946 until his death twenty-two [sic] years later, Bill and I had an intense (though always platonic) relationship, mostly happy though often rivalrous. Bill envied my slicker musical know-how and the footing I already had in the professional world. I envied his Jesuit education (my own non-musical training had been catch-as-catch-can) as well as an intellect that was quicker than mine. Decent looking if not handsome, he was vain of his person, and certainly his blue, blue eyes, as violent as they were kind, remain unforgettable, offset as they often were by his pale lavender T-shirts and tinted blond crew cut. Once he joined the American Composers Alliance in 1959 and became an “official” published composer, Bill lopped three years off his age, as Tennessee Williams had done, on the grounds that those years had vanished into the bottle, as well as into the thin air of vain aspiration. Actually he was two months older than I. When I returned for good from France in 1957, we grew closer. Between 1959 and 1961, acting on the premise that the simple Art Song might still prove vital in a period (this is apparent in retrospect) of highest instrumental complexity, we launched a successful series in Carnegie Recital Hall called “Music for the Voice by Americans”. The common current practice of composers presenting themselves as stars was then unprecedented. We had guest stars, too, notably Copland and Thomson, accompanying their own songs, and our vocalists included Patricia Neway, David Lloyd, Phyllis Curtin, Regina Sarfaty, Reri Grist, Veronica Tyler, all in full bloom, and representative of a now-vanished breed—the recital singer. If we were partners in art as well as in crime, criticizing each other by day, cruising Eighth Street bars together by night, there were no emotional entanglements. Bill lived much of his adult life with Edward Albee, whose phenomenal success as a playwright became an obsession with him. When Edward rose, Bill, on a seesaw, sank. This is clear as I reread his old letters.[15]

The closeness of the two men’s relationship—a platonic one, as Mr. Rorem more than once asserted—cannot be overstated. Significantly, it was Mr. Rorem whom the authorities contacted upon finding Mr. Flanagan dead in his apartment in 1969.[16] Several months later, Mr. Rorem and Mr. Albee organized a memorial concert in Mr. Flanagan’s honor, held on April 14, 1970 at the Whitney Museum of American Art, where Aaron Copland and Mr. Rorem both eulogized Mr. Flanagan. Mr. Albee eventually founded the William Flanagan Memorial Creative Persons Center at Montauk on Long Island, New York. Maintained by the Edward F. Albee Foundation, the Center’s announced mission is to serve writers and visual artists from all walks of life by providing time and space in which to work without disturbance.

I have cited Eastman students observing National Coming Out Day 2003, and also the moment when a renowned and esteemed Eastman alumnus broke the silence on what had been a dark chapter in the Eastman School’s history. These were two noteworthy occasions in the year 2003 that demonstrated forward motion towards a more just school environment. The students who organized to observe National Coming Out Day that October did so openly in a supportive environment, and without fear of reprisal; William Flanagan, expelled in 1946, could hardly have dreamed of such. Whether a completed Eastman degree would have appreciably altered or enhanced William Flanagan’s professional trajectory remains an open question. The unalterable fact is that a talented and promising creative individual was expelled in punishment for his sexual orientation. The best that we might hope for now would be for accountability in the form of information brought to light to serve the historical record. This week at Eastman, in October, 2024, let us join in solidarity with our students who are observing National Coming Out Day. Let us all renew our dedication to living out our MELIORA values and to realizing full diversity, equity, and inclusion within our school community.

[1] While National Coming Out Day is officially observed on October 11th each year, the Eastman observance on October 10th was presumably timed to maximize visibility at school on a weekday.

[2] Eastman Notes began its run as Notes from Eastman in 1966. The complete run of issues is archived at Ruth T. Watanabe Special Collections in the Sibley Music Library.

[3] Dr. Eichberg’s book Coming Out: An Act of Love (Plume, 1991) was immediately influential upon its publication. He died of AIDS-related complications in 1995 at the age of 50.

[4] Ms. O’Leary (1948-2005), a former nun who came out as a lesbian, shared her personal journey in the book Lesbian Nuns: Breaking Silence (Naiad Press, 1985). In 1972 she had been one of the founders of the Lesbian Feminist Liberation.

[5] The published literature on the history of the AIDS crisis/epidemic/holocaust (each of those three words was in the AIDS lexicon of the day), on its social and moral aspects, on the record of action/inaction by the U.S. Government, and the responses by the worldwide medical community, is voluminous. For just one title from the U.S. literature, I earnestly recommend Reports from the holocaust: the making of an AIDS activist (St. Martin’s Press, 1989) by playwright and activist Larry Kramer (1935-2020), who gained notoriety and influence as one of the founders of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis and also of ACT UP (the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power).

[6] Francis James (Jim) Brown (1925-2008), composer, a native of Rochester, New York and alumnus of the Eastman School of Music. Mr. Brown spent most of his professional life in the UK and in Greece. Today his manuscripts and professional papers are archived at the Sibley Music Library; a finding aid is accessible on the SML website.

[7] 78th Commencement, Eastman School of Music, Sunday, May 18, 2003. Recorded by the office of Technology and Media Production and preserved in the Eastman Audio Archive, call no. MO 1258. I am grateful to recording engineer Mike Farrington for his assistance in transferring the audio content from its original capture.

[8] Confidentiality policies precluded the sharing of any further information with me. I am grateful to my colleagues in the Registrar’s Office for their consideration in confirming the dates of the late William Flanagan’s enrollment.

[9] Composer David Diamond (1915-2005), a native of Rochester, New York and alumnus of the Eastman School of Music, maintained his own distance from the Eastman School to the end of his life as a result of his own personal tensions. Dr. Nadine Hubbs cited Mr. Diamond in her excellent book The Queer Composition of America’s Sound: Gay Modernists, American Music, and National Identity (University of California Press, 2004).

[10] A truly respectful appreciation of Mr. Flanagan and his work, written by Lester Trimble, was published in Stereo Review shortly after Mr. Flanagan’s death.

[11] Further, in the journal literature one finds a fulsome appreciation of Mr. Flanagan’s career by Edward Albee, published together with a catalogue of Mr. Flanagan’s works, compiled by Mr. Rorem. “William Flanagan” in the American Composers Alliance Bulletin, IX/4 (1961), 12-19.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Notwithstanding this omission, Mr. Strouse on record elsewhere stating that Mr. Flanagan was expelled from Eastman following “a gay incident”. “Charles Strouse struts his stuff” in Gay City News, August 7, 2008. Accessed on October 7, 2024.

[14] Put on a Happy Face: A Broadway Memoir (Union Square Press, 2008). The quotations in this paragraph comes from pages 19 and 180.

[15] From the diary entry for September 12, 1987 in Lies: A Diary, 1986-1999 (Counterpoint, 2000), pages 101-102.

[16] The Later Diaries of Ned Rorem, 1961-1972 (North Point Press, 1983), page 270.