Online exhibit from the Ruth T. Watanabe Special Collections; curated by Gail E. Lowther.

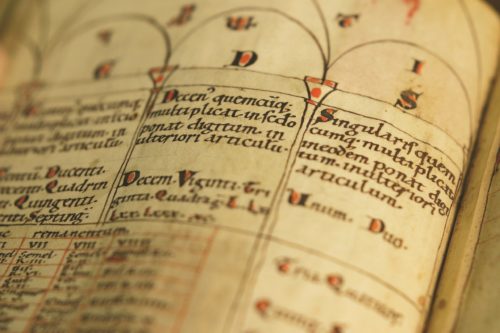

The Rochester Codex is the oldest item at Sibley Music Library. This unique manuscript dates from the late 11th century (ca. 1017–1103) and is a compilation of treatises on the medieval arts of arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy, commonly known as the medieval quadrivium. Among its contents are significant treatises on music by four 11th-century German scholars—namely Bern of Reichenau (d. 1048), Hermann of Reichenau (1013–1054), Wilhelm of Hirsau (d. 1091), and Frutolf of Michelsberg (d. 1103)—making the codex an important source for 11th-century German speculative music theory.

The Rochester Codex is the oldest item at Sibley Music Library. This unique manuscript dates from the late 11th century (ca. 1017–1103) and is a compilation of treatises on the medieval arts of arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy, commonly known as the medieval quadrivium. Among its contents are significant treatises on music by four 11th-century German scholars—namely Bern of Reichenau (d. 1048), Hermann of Reichenau (1013–1054), Wilhelm of Hirsau (d. 1091), and Frutolf of Michelsberg (d. 1103)—making the codex an important source for 11th-century German speculative music theory.

In 2020, the Codex was digitized at the University of Rochester’s Digitization Lab by Lisa Wright, Digitization Specialist, and Clara Auclair, Graduate Student Digitization Specialist and PhD candidate in Visual and Cultural Studies at the University of Rochester, using state-of-the-art reprographic equipment and software. Thanks to their efforts, the Rochester Codex is now available online via high quality images in full color, making this rare treasure accessible to scholars and researchers worldwide.

On Display

1

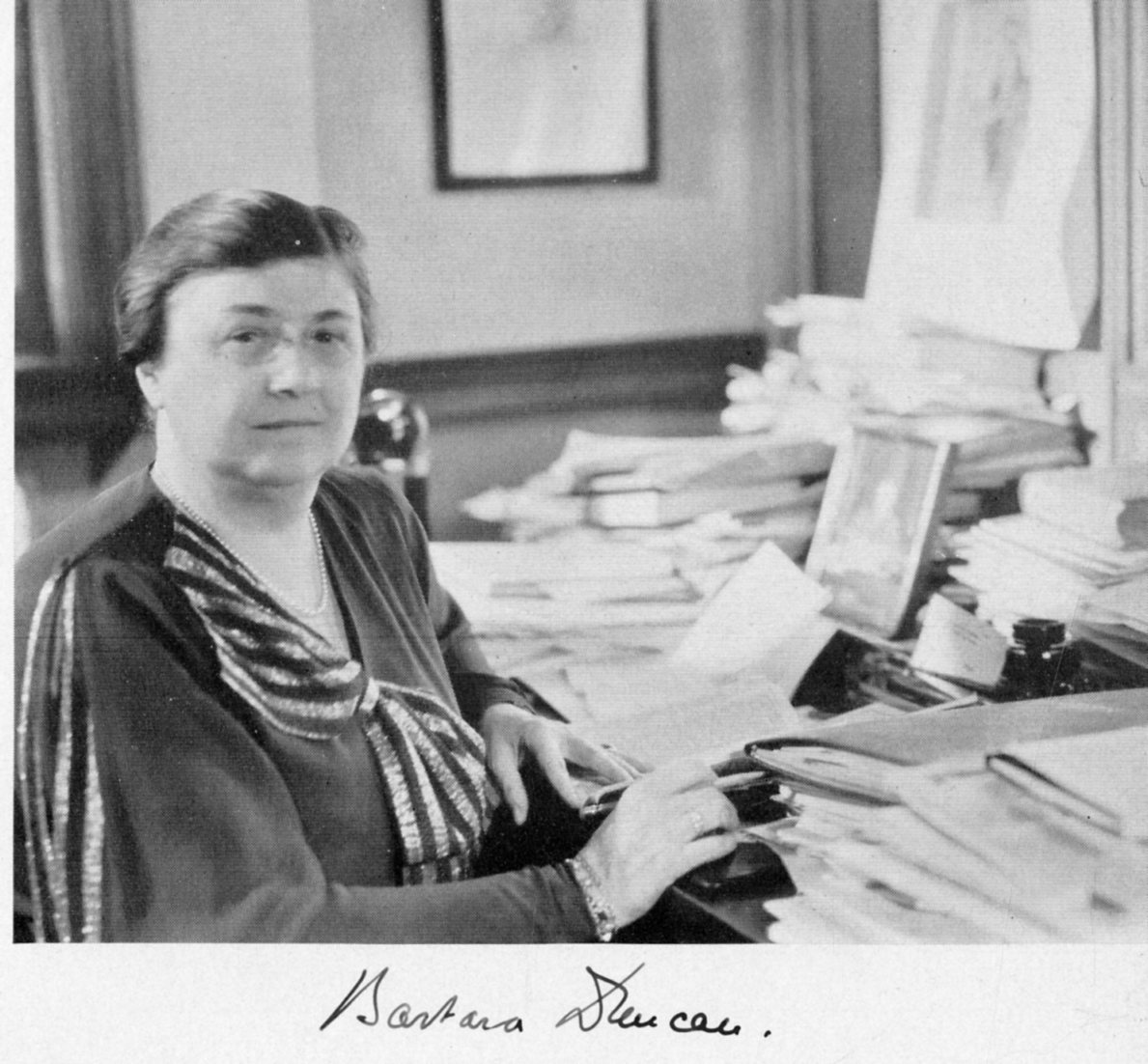

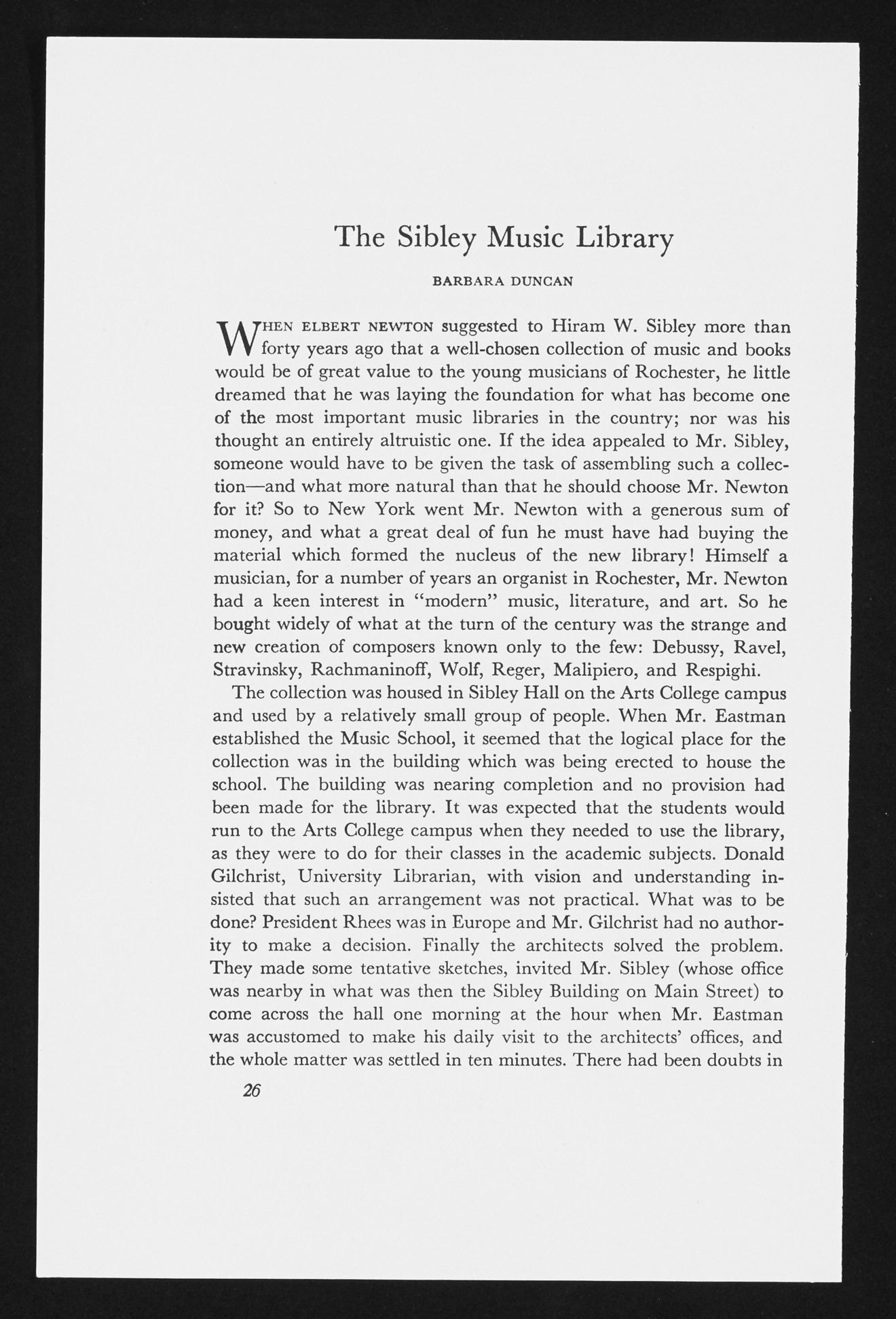

The codex has resided at Sibley Music Library (SML) since 1929, when it was purchased by Barbara Duncan, SML’s first director, as part of her work to build the library’s research and rare books collections. In 1928 and 1929, the vast personal library of Dr. Werner Wolffheim (1877–1930), a German music critic and collector, was sold at a two-part auction in Berlin. Miss Duncan attended the June 1929 sale at the behest of SML founder Hiram Watson Sibley, who reportedly told her to “buy something we can talk about.” And that she did. Her 1929 trip to Berlin was, arguably, the single most profitable buying spree in SML’s history. In addition to the 11th-century codex, now popularly known as the Rochester Codex, Miss Duncan or her agent purchased some six dozen titles from Dr. Wolffheim’s library, including autograph manuscripts of short compositions, sketches, or score fragments by Purcell, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Rubenstein, and Schubert. SML also acquired several dozen individual leaves from medieval and renaissance manuscripts that had been collected by the German musicologist Oskar Fleischer (1856–1933) in the course of his research on the development of western European music notation systems (now the Oskar Fleischer Collection). Additionally, during the same trip, Miss Duncan took the opportunity to purchase valuable items from other vendors—most notably, the short-score manuscript of Debussy’s La Mer that the Parisian dealer Robert Legouix was offering.

Miss Duncan later recounted the Wolffheim auction in an article in the University of Rochester Library Bulletin:

In June, 1929, I attended the sale of the second portion of the library of Dr. Werner Wolffheim in Berlin. As I started out on my trip, Mr. Sibley said, “Buy something that we can talk about!” So as Item No. 1 in the catalogue seemed to answer that description, we bought it. “It” was a codex written in the eleventh century in southern Germany, probably at the convent of Reichenau, consisting of treatises on the arts of the Middle Ages, which, of course, included music. Johannes Wolf was bidding for the Prussian State Library and I shall never forget the expression on his face as the precious volume was knocked down to us and he leaned out and looked down the table at me reproachfully. I felt a little ashamed to think that just because we had more money than he had at his disposal the codex was going to leave its native land.

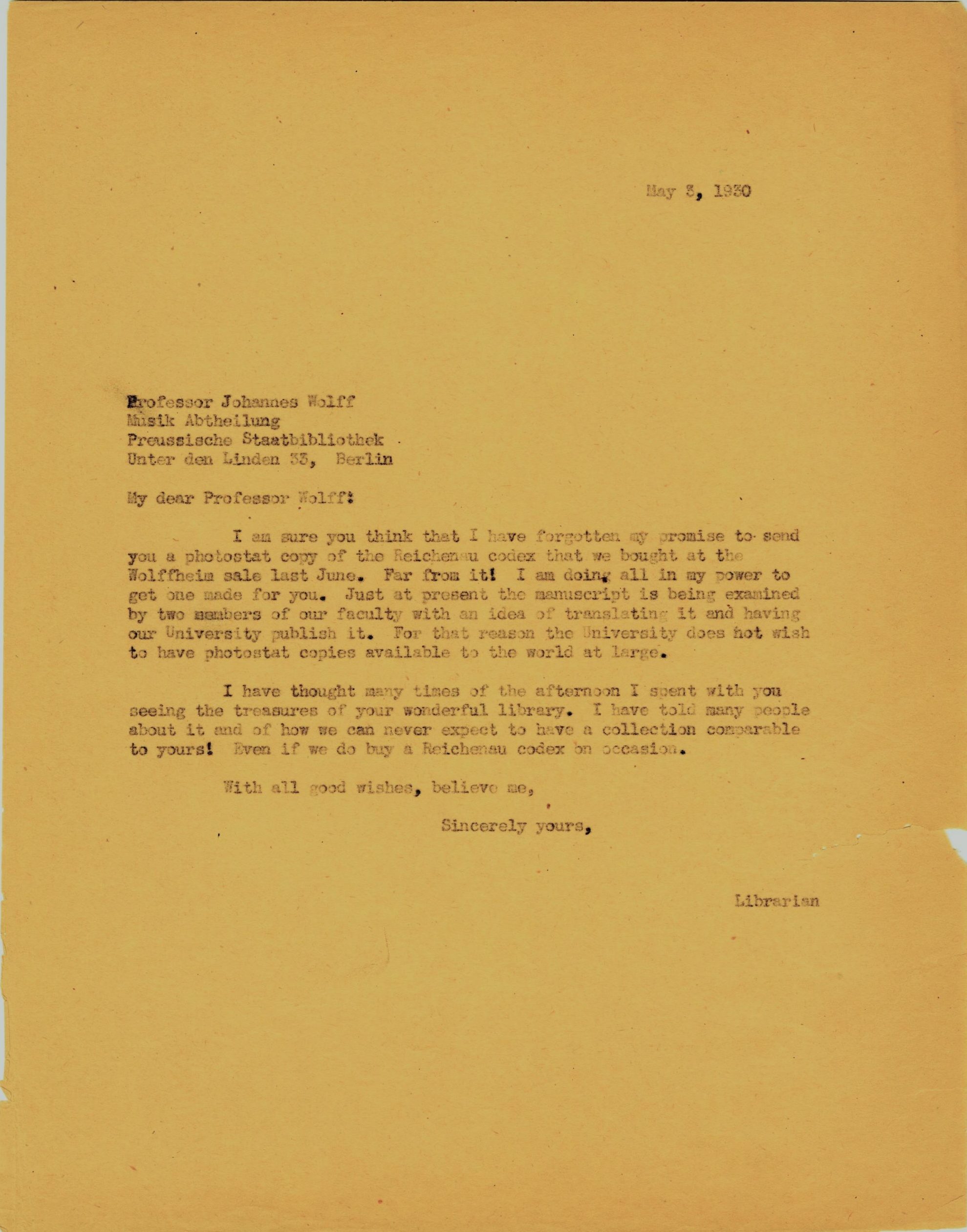

Several months after the auction, Miss Duncan sent a courtesy letter to Dr. Johannes Wolf, Director of the Prussian State Library, whom she had outbid to purchase the 11th-century codex. The letter ends with a typically wry Duncan comment—which was perhaps injudicious in this instance, considering that she had bested Wolf in the auction, thereby causing a German treasure to be removed from its homeland:

I have thought many times of the afternoon I spent with you seeing the treasures of your wonderful library. I have told many people about it and of how we can never expect to have a collection comparable to yours! Even if we do buy a Reichenau codex on occasion.

2

The two-volume catalogue for the Wolffheim auction included an extensive description of the codex—totaling 7 pages in all—with a detailed summary of each treatise in the volume. The copy of the catalogue preserved in SML’s rare books collection—excerpts from which are shown above—is presumed to have been Miss Duncan’s own copy from the auction, with her penciled notes in the margins; the call numbers for items now held in SML’s collections (e.g., Vault ML92 .1100 for the Rochester Codex) were added later by a staff librarian, following standard practice for published bibliographies in SML’s reference collections. The level of detail in the description of the codex is characteristic of that in the remainder of the catalogue—which later led collector and dealer Albi Rosenthal (1914-2004) to note its lasting value as “a standard work of bibliographical reference.”[1]

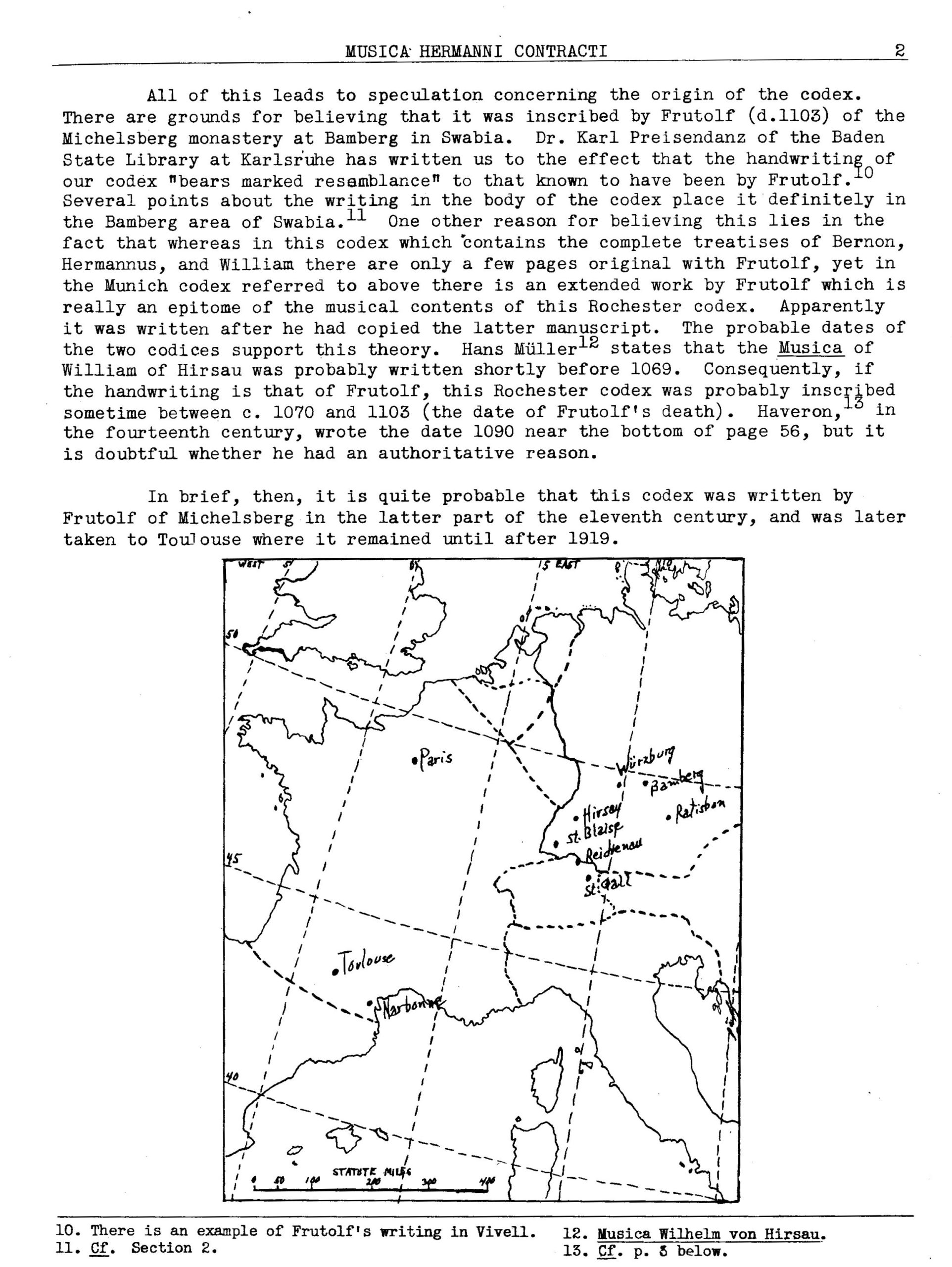

The first focused study of the codex was completed by ESM alum Dr. Leonard W. Ellinwood (1905–1995) in 1934 for his master’s thesis (“Musica Hermanni Contracti,” MM thesis, Eastman School of Music, 1934). Ellinwood’s thesis included a more comprehensive examination of the volume’s provenance and history as well as a new transcription and English translation of its most noteworthy treatise: Musica by Hermann of Reichenau (commonly referred to as Hermannus Contractus; 1013–1054). The Rochester Codex contains one of only two extant copies of Hermann’s complete treatise on music. Ellinwood’s translation was later published in expanded form as Eastman School of Music Studies No. 2 (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester, 1936).

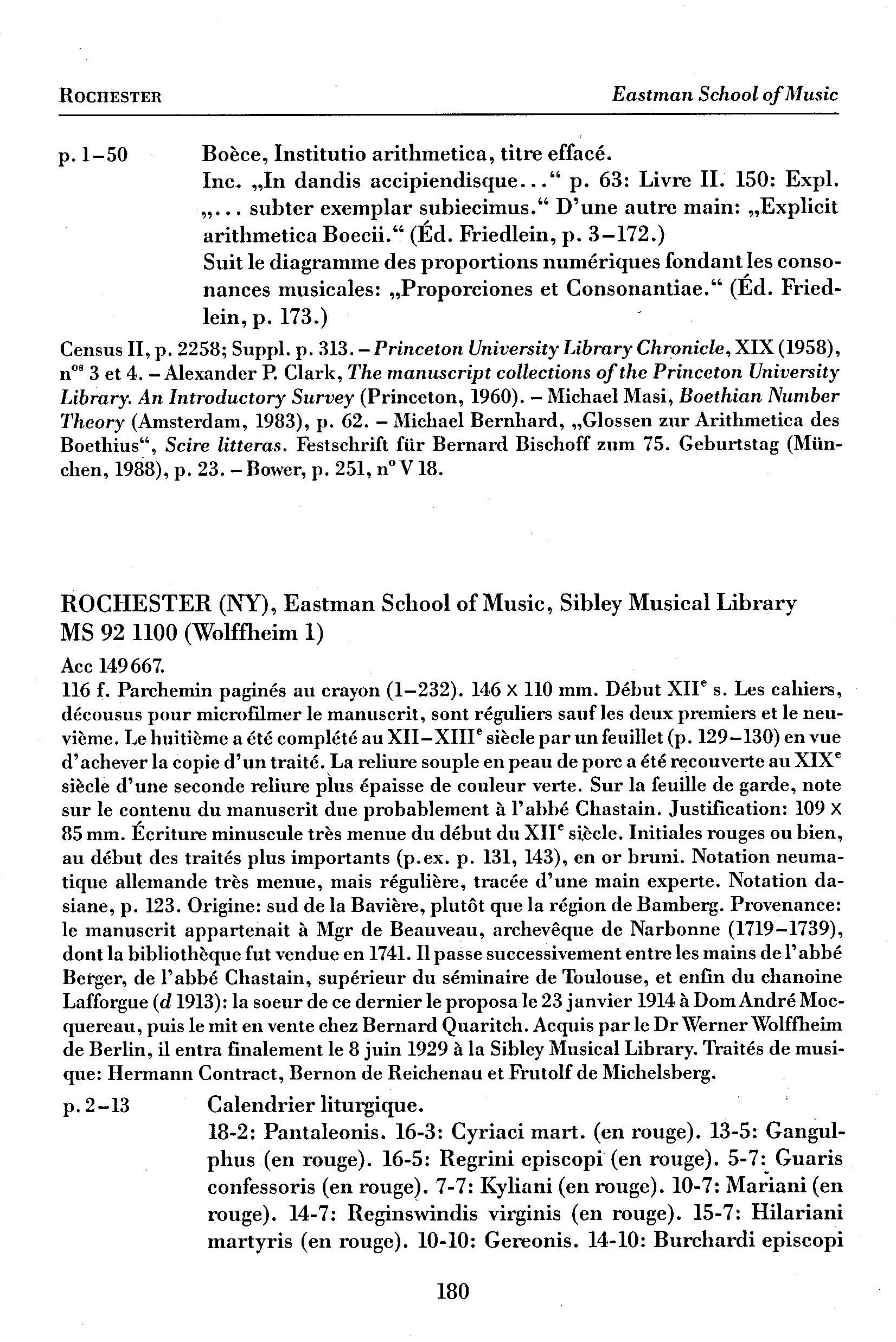

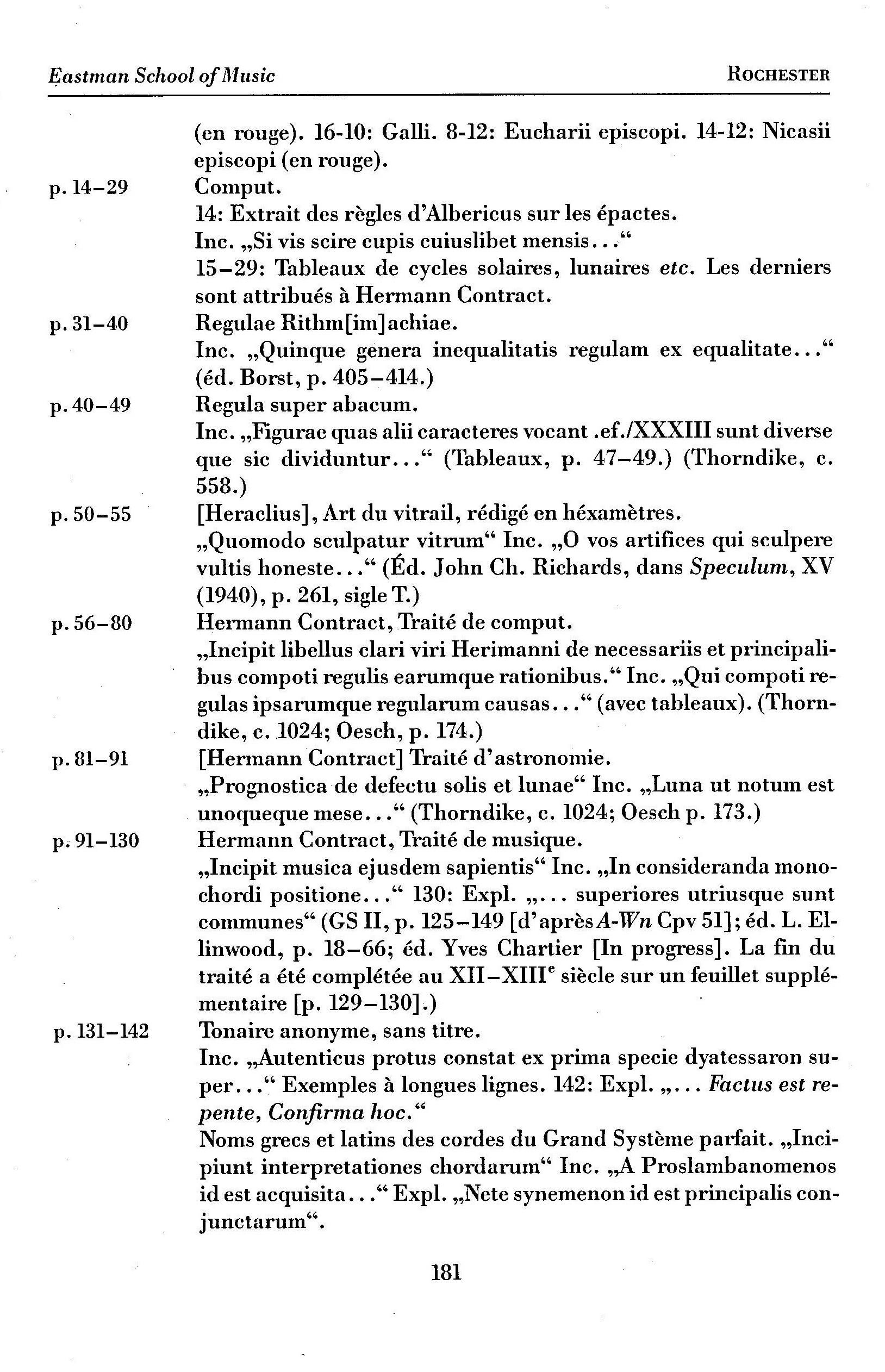

Additional descriptions of the Rochester Codex—both of which reflect more recent scholarship on its contents and the constituent writers and scribes—are contained in the RISM Catalog, Series B/III/4 (The Theory of Music. Manuscripts from the Carolingian Era up to c. 1500 in Great Britain and in the United States of America: Descriptive Catalogue, part 2), as well as in John L. Snyder’s revised edition of Ellinwood’s translation of Hermann’s Musica (The Musica of Hermannus Contractus, Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2015).

3

The Rochester Codex originated in southern Germany and dates to the late 11th or 12th century. It contains treatises on music by four 11th-century German scholars, namely Bern of Reichenau (d. 1048), Hermann of Reichenau (1013–1054), Wilhelm of Hirsau (d. 1091), and Frutolf of Michelsberg (d. 1103). The codex also contains a technical treatise on stained glass (an excerpt from De coloribus et artibus Romanorum, ca. 10th century) and multiple treatises, in whole or in part, on astronomy and arithmetic, including further content attributed to Hermann of Reichenau.

For much of the medieval era, Reichenau was a prominent center of intellectual, artistic, and spiritual life in Europe. The Reichenau monastery (pictured above) had been founded in 724 on an eponymous island in Lake Constance (known in German as Bodensee), which is situated at the border of the modern states of Germany, Austria, and Switzerland (see map above). The Reichenau monastery school was established in the late 8th century under Abbot Waldo (786–806). By the early 9th century, Reichenau had built one of the largest libraries in Europe and solidified its reputation and influence as a leading center of education. Two of the scholars represented in the Rochester Codex—Abbot Bern of Reichenau (d. 1048) and his pupil Hermann of Reichenau (1013–1054)—would have written their treatises at the monastery.

4

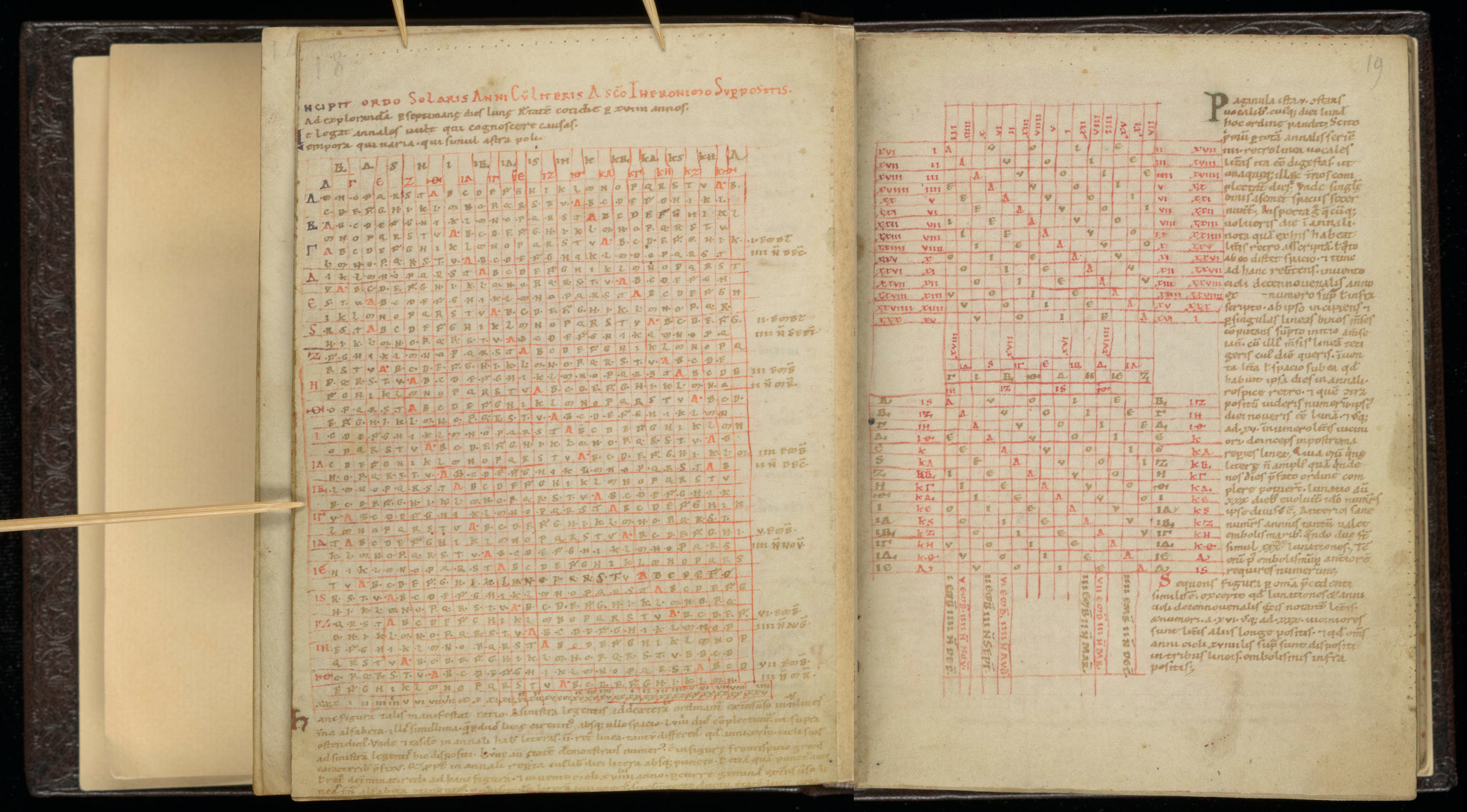

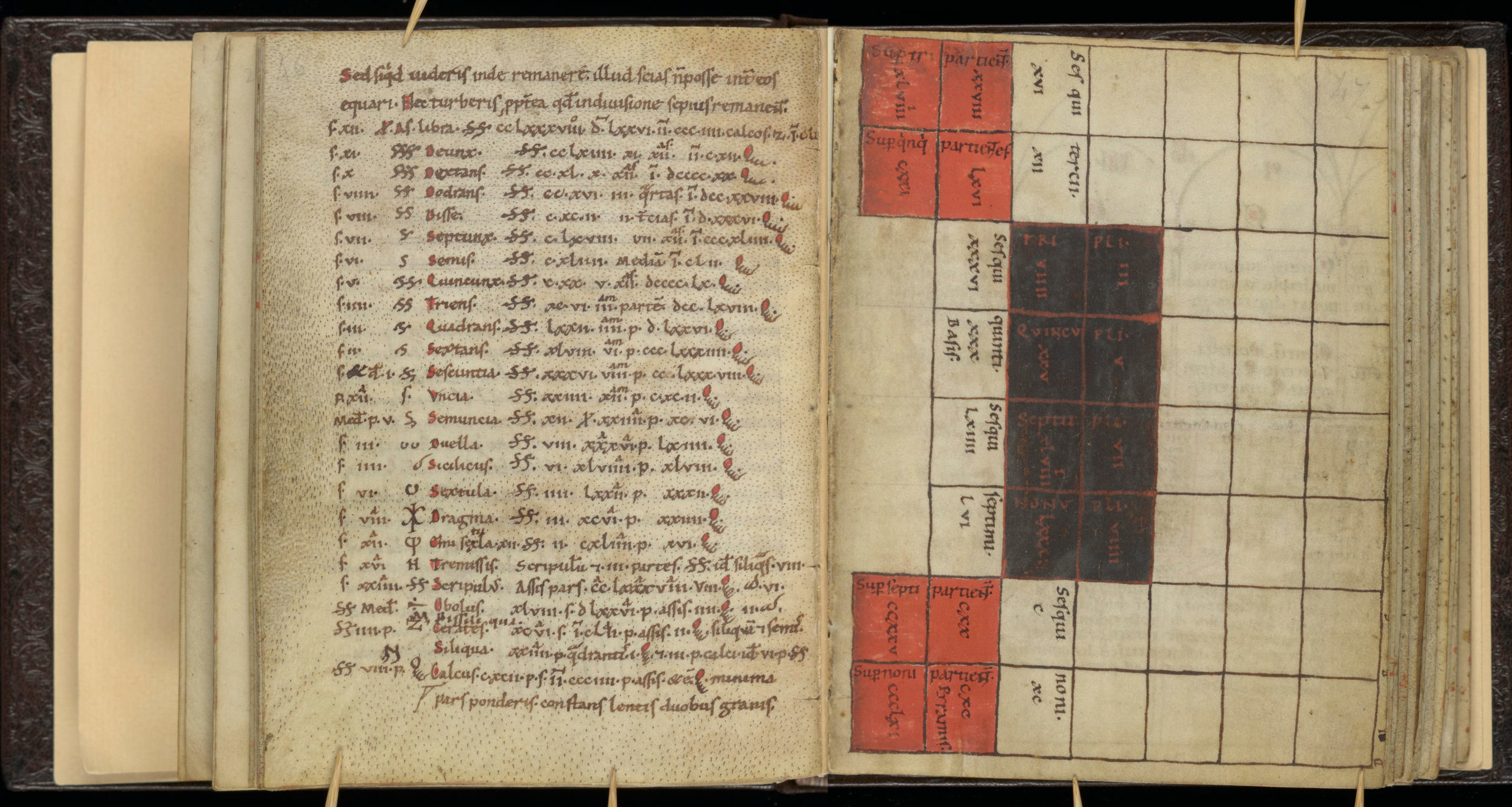

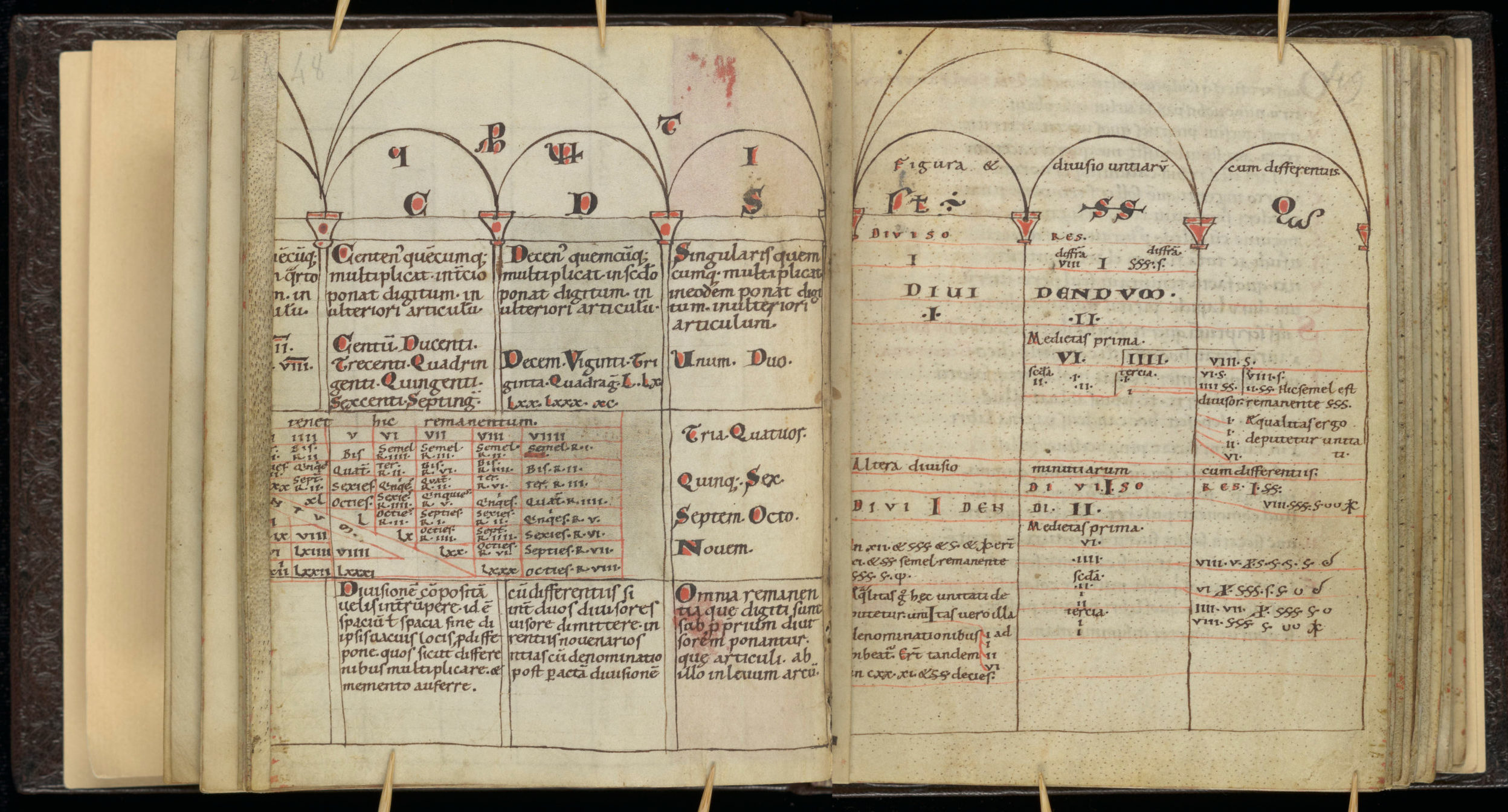

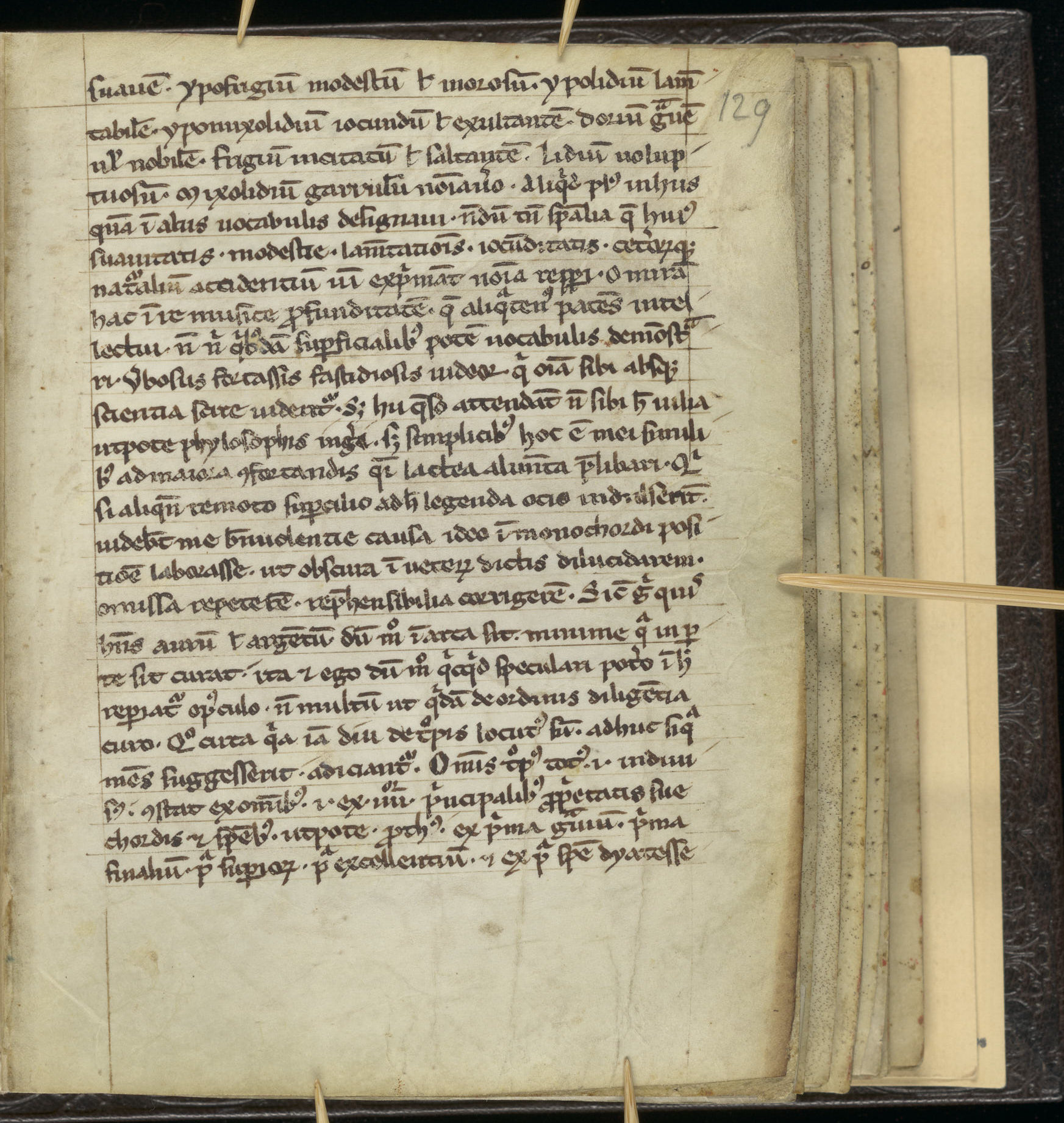

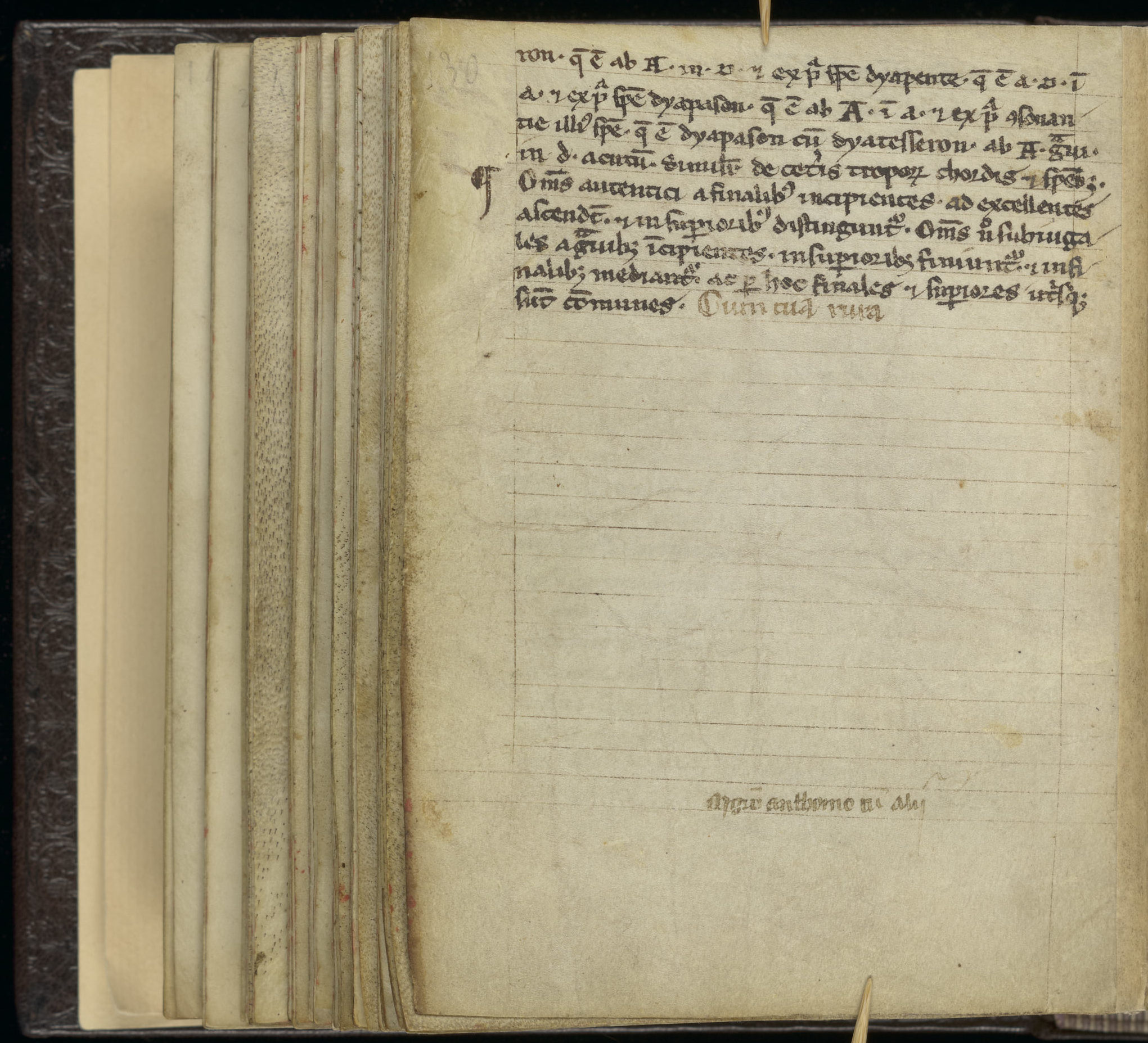

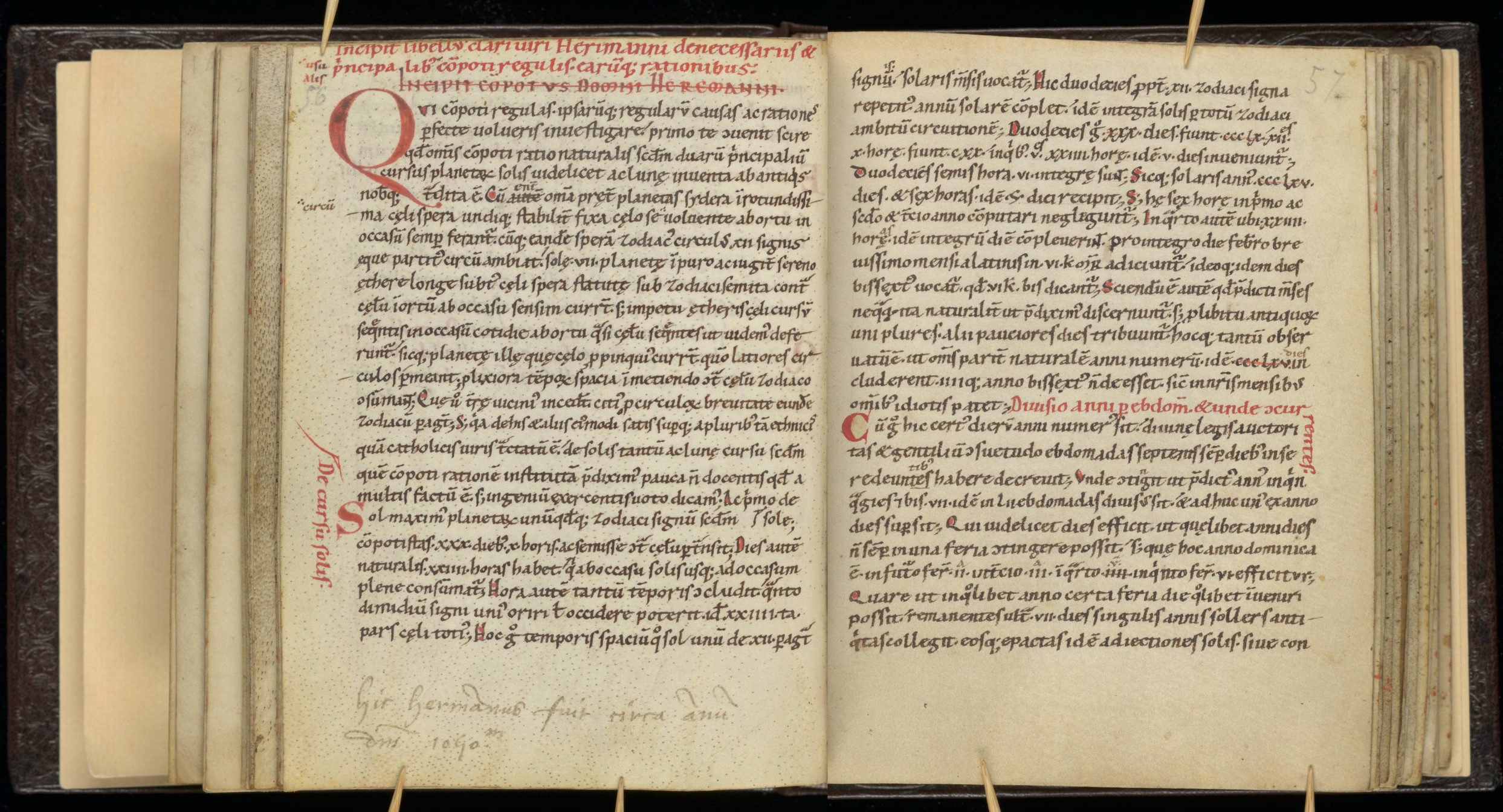

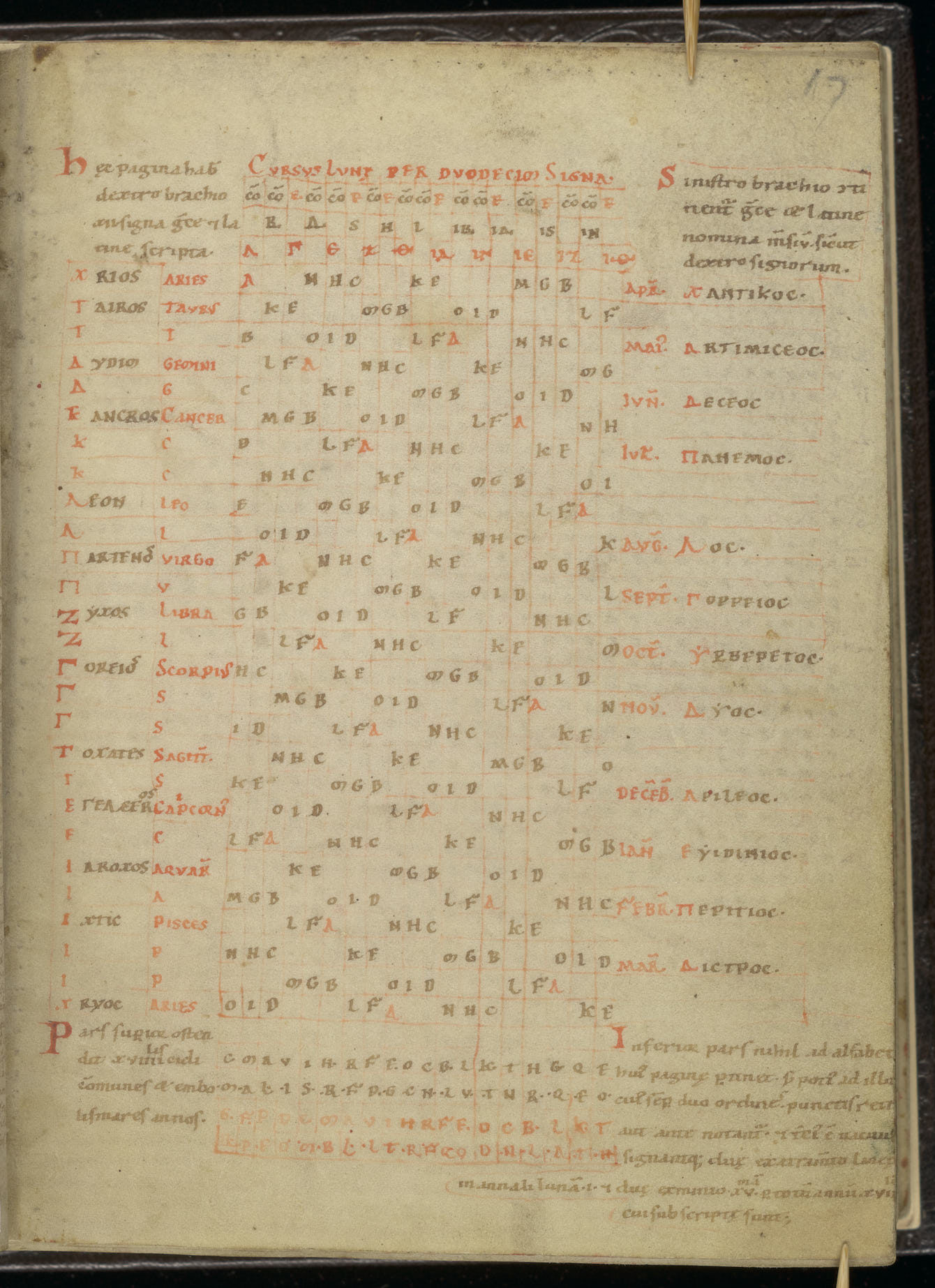

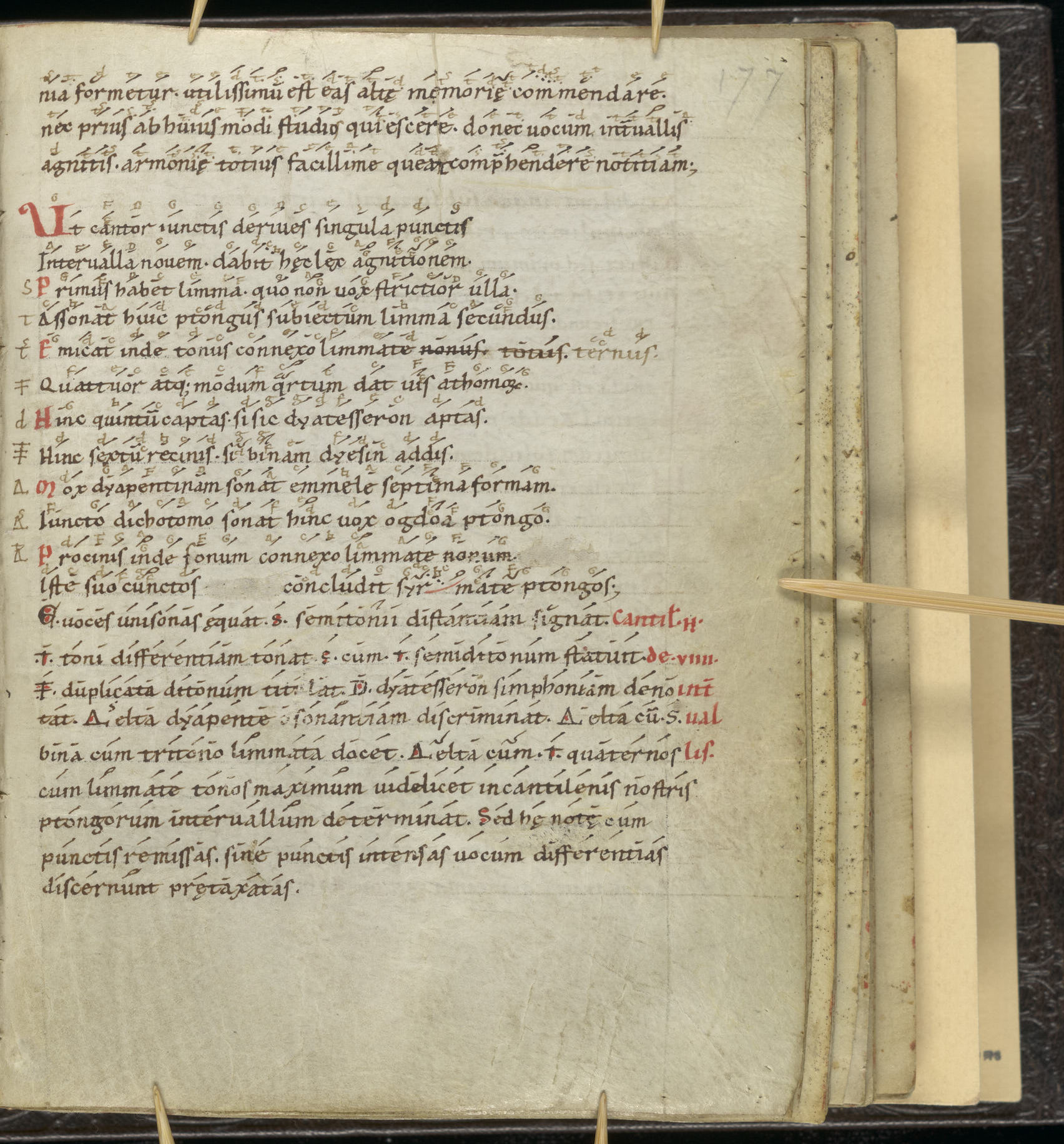

According to Ellinwood, paleographic analysis of the handwriting indicates there were three principal scribes: Scribe A, writing in Carolingian miniscule, which Ellinwood dates to the 10th century (pages 2–29, comprising a calendar of saint’s days and four tables of the solar year); Scribe B, writing in a similar hand to Scribe A but on poorer quality vellum (pages 31–46, comprising two treatises on arithmetic); and Scribe C, who copied the remainder of the codex, writing in a late German Carolingian (or transitional or protogothic) miniscule (pages 47–232). One page of the codex (pages 129–130) was evidently lost and has been replaced with a leaf written in what appears to be a late 12th- or early 13th-century French book hand that is almost a pure Gothic script. The same hand also appears to have added many corrections to Hermann’s Compotus (a treatise on calculating astronomical events and moveable feasts; pages 56–91) and also annotated some of the songs in the codex with Hermann’s style of interval notation, which used Greek and Latin letters to indicate intervals (pages 176–180).

Ellinwood, based on his analysis and in consultation with Dr. Karl Preisendanz (then a leading German paleographer), suggested that Scribe C may have been Frutolf of Michelsberg (d. 1103), given a “marked resemblance” of the writing in the Rochester Codex to writing known to have been by Frutolf[2]—a conclusion that more recent scholarship has avoided in favor of a more conservative analysis.[3] However, modern scholars have endorsed Ellinwood’s determination that the codex originated in southern Germany in the Bavaria region. (N.B. Ellinwood attempted to locate the codex’s origins even more precisely to the vicinity of Würzburg—a conclusion taken from the contents of the saint’s calendar at the beginning of the codex [excerpt shown above]—and nearby Bamberg, where Frutolf would have copied the final section, if the latter pages are in his hand.)

5

Although the codex was almost certainly copied in southern Germany, the French hand on the replaced leaf (pages 129–130) suggests that the volume may have been moved to France, likely Toulouse, in the first part of the 13th century, if not earlier. Further evidence to support this conclusion is the name “Magister Anthonio di Ulý,” which is written on the replacement leaf at the foot of page 130. Ellinwood suggested this may refer to Saint Anthony of Lisbon (in Latin Antonii Ulyssiponensis), more commonly known as Saint Anthony of Padua (1195–1231), who served as a magister (or teacher) at Toulouse and Montpellier during the years 1224–1226.[4]The ownership of the codex from the 18th century on is comparatively well known thanks to scholars who used or described the codex in their writings. By the mid-1700s, it was part of the library of René François de Beauvau du Rivau (1664–1739), Archbishop of Toulouse (1713–1739) and Narbonne (1719–1739). In fact, the first page of the codex bears the name “Msgr. de Veauveau, Archevêque de Narbonne” in boldscript. By 1867, it was in the possession of Abbé Berger of Toulouse, and in 1919, the codex was owned by Abbé G. Lafforgue, curé of Croix-Daurade in Toulouse. Thus, Dr. Wolffheim would have acquired it in the 1920s, not long before his collection was put up for auction and the codex purchased by SML.

6

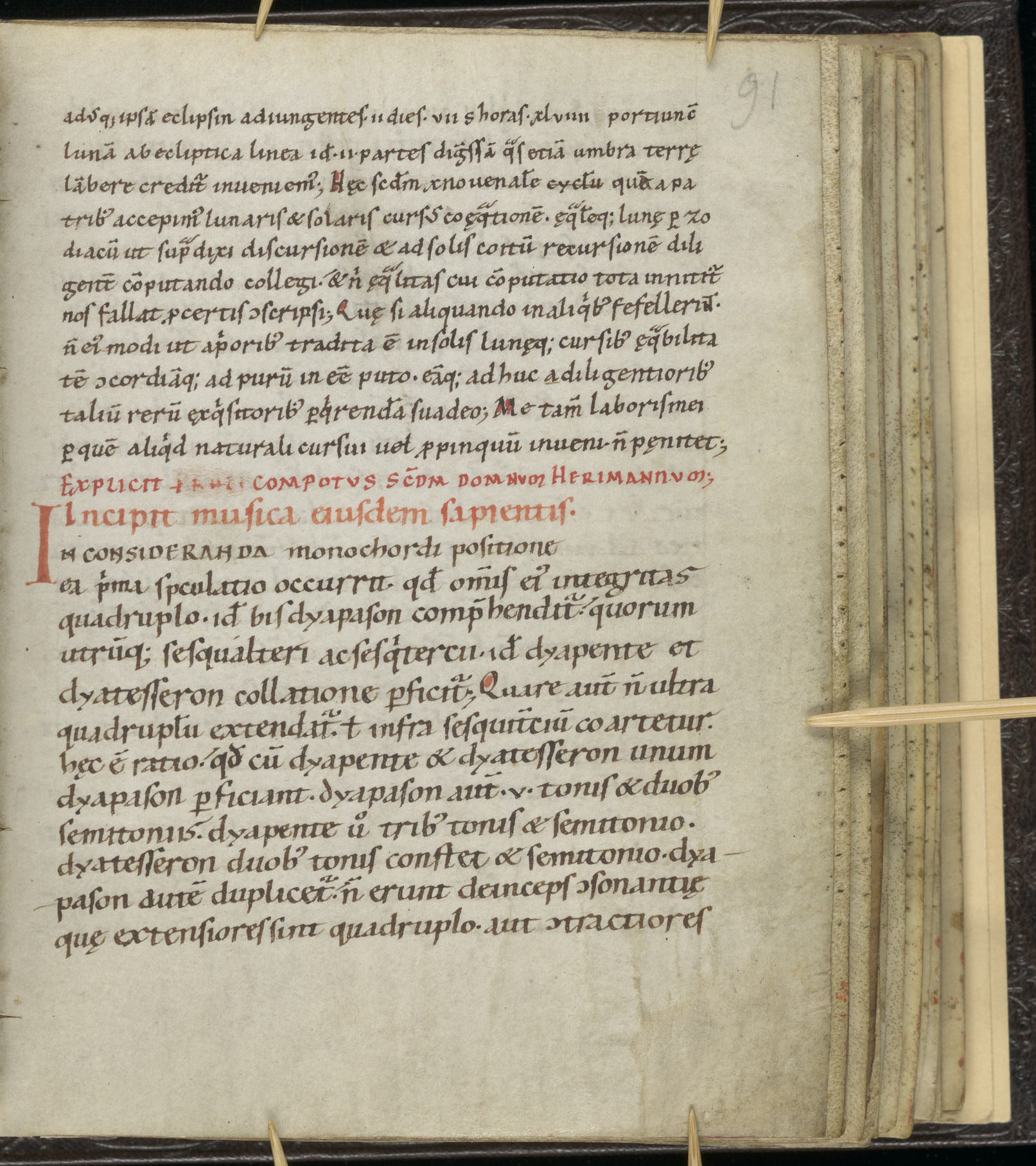

Most of the scholarly attention on the Rochester Codex has focused on the treatise on music by Hermann of Reichenau (pages 91–130), as it is one of only two complete sources for the treatise. However, the codex also contains Hermann’s Compotus, a treatise on methods for calculating astronomical events and moveable feasts (in two books, pages 56–91; the beginning of the Compotus is shown above), and his treatise on astronomy (Prognostica de defectu solis et lunae, pages 81–91). Additionally, one of the Codex’s tables of lunar cycles (page 17, shown above) is attributed to him, as are multiple verses included within the excerpts from Frutolf’s Breviarium de musica et tonarius (Hermann’s verses are on pages 177 and 180).

Hermann (in Latin Hermannus Augiensis) (b. July 18, 1013, Swabia; d. September 24, 1054, Reichenau), was an 11th-century monk, chronicler, scholar, and composer. Details of his life and accomplishments were preserved by his pupil, Berthod of Reichenau (ca. 1030–prob. 1088), in a detailed biography or vita, Hermann was traditionally distinguished in Latin as Hermannus Contractus or “Herman the Lame” in reference to a significant physical disability, likely from a congenital or childhood infirmity or injury, that seriously limited his mobility and also affected his speech. He was sent to school at the age of seven and spent his adult life as a chronicler and scholar in the monastery at Reichenau. His chief work is a detailed chronicle of world events (Chronicon ab urbe condita ad annum 1054), which is a valuable source of historical information, particularly for the late 10th and early 11th centuries.

Hermann also had a reputation for great learning. Besides German (likely Old High German) and Latin, he is reported to have also known Greek and possibly Arabic and Hebrew. Hermann completed treatises on all subjects of the medieval quadrivium—astronomy, arithmetic, geometry, and music. As noted above, three of his treatises (on arithmetic, astronomy, and music, respectively) are included in the Rochester Codex, and a further eight treatises by Hermann on arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy are preserved in other codices.

7

Hermann’s treatise on music, i.e., Musica, has long been considered a principal source for 11th-century German speculative music theory. The other complete copy of Hermann’s Musica is contained in a 12th-century codex now held by the Austrian National Library in Vienna (MS Vienna, Nationalbibliothek, Cod. 51, folios 82r–90r). In 1784, the first known modern edition of Hermann’s Musica was produced by the German theologian and historian Martin Gerbert (1720–1793) as part of his 3-volume Scriptores ecclesiastici de musica sacra (1784), which was a collection of the principal writers on church music from the 3rd century until the invention of printing. A second, stand-alone edition of Musica was produced 100 years later by Wilhelm Brambach (1841–1932), a German classical scholar and music historian, which aimed to correct various errors in Gerbert’s edition (Hermanni contracti musica, Leipzig, G. Teubner, 1884). Yet, as Ellinwood noted in his 1934 edition (and master’s thesis), the copy of Hermann’s Musica in the Rochester Codex (pages 91–130) contains some substantive differences from the Vienna Codex—principally wording differences or omissions. In almost all such instances, the Rochester Codex has the superior reading. Thus, Ellinwood’s edition, as the first to incorporate both complete sources of Hermann’s Musica, was quickly preferred over the earlier versions. The recent edition by John Snyder (2015) takes into account a third, albeit incomplete, source—from a codex held by the Kassel University Library (Ms. 4° Mss. Math. 1, Kassel, Landesbibliothek und Murhardsche Bibliothek der Stadt Kassel). While Snyder’s edition remains quite faithful to that of Ellinwood, Snyder did make extensive revisions to the transcription and English translation of the treatise to follow current practice in the field, while also adding new appendices, greatly expanded indexes, and more detailed critical notes.

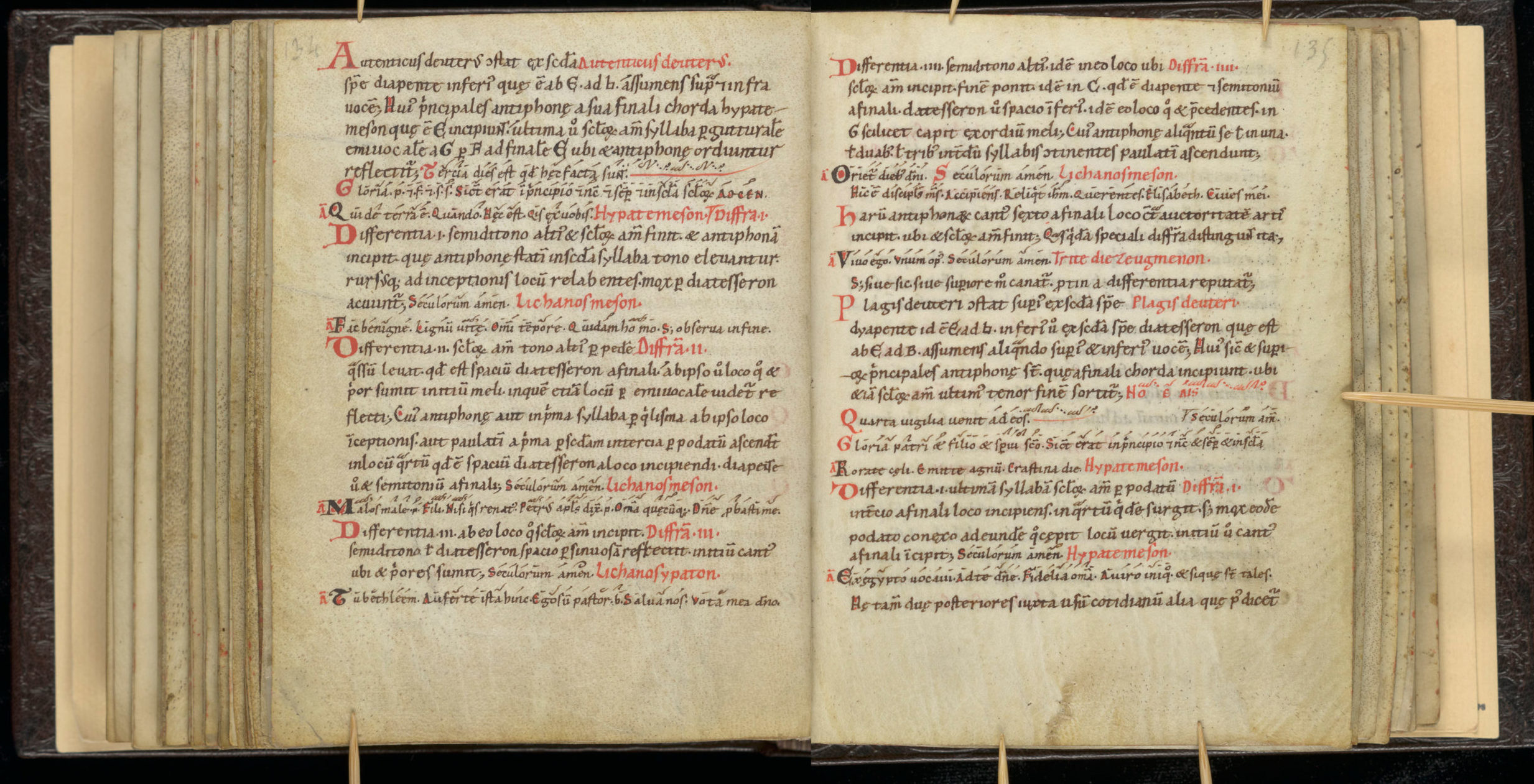

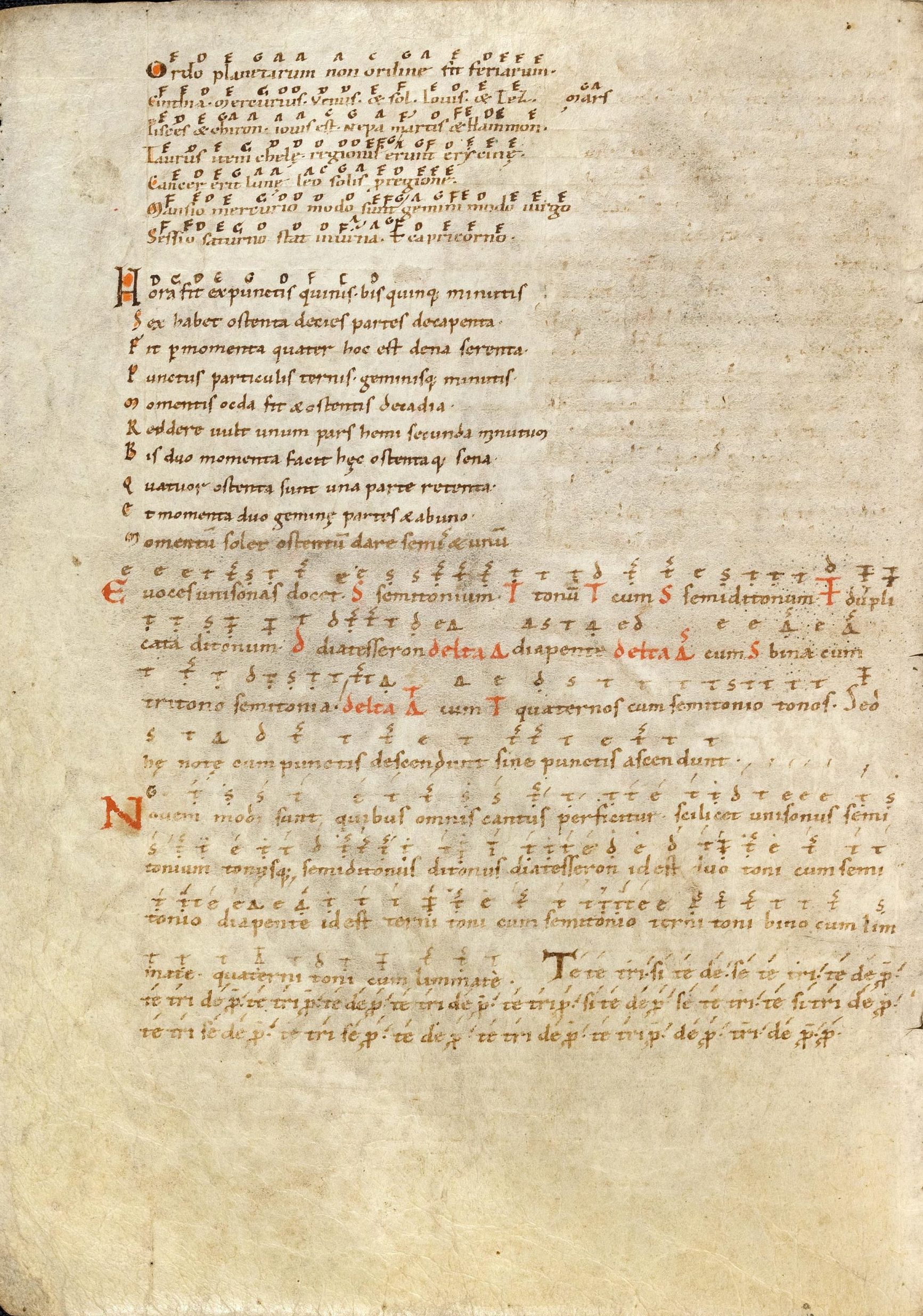

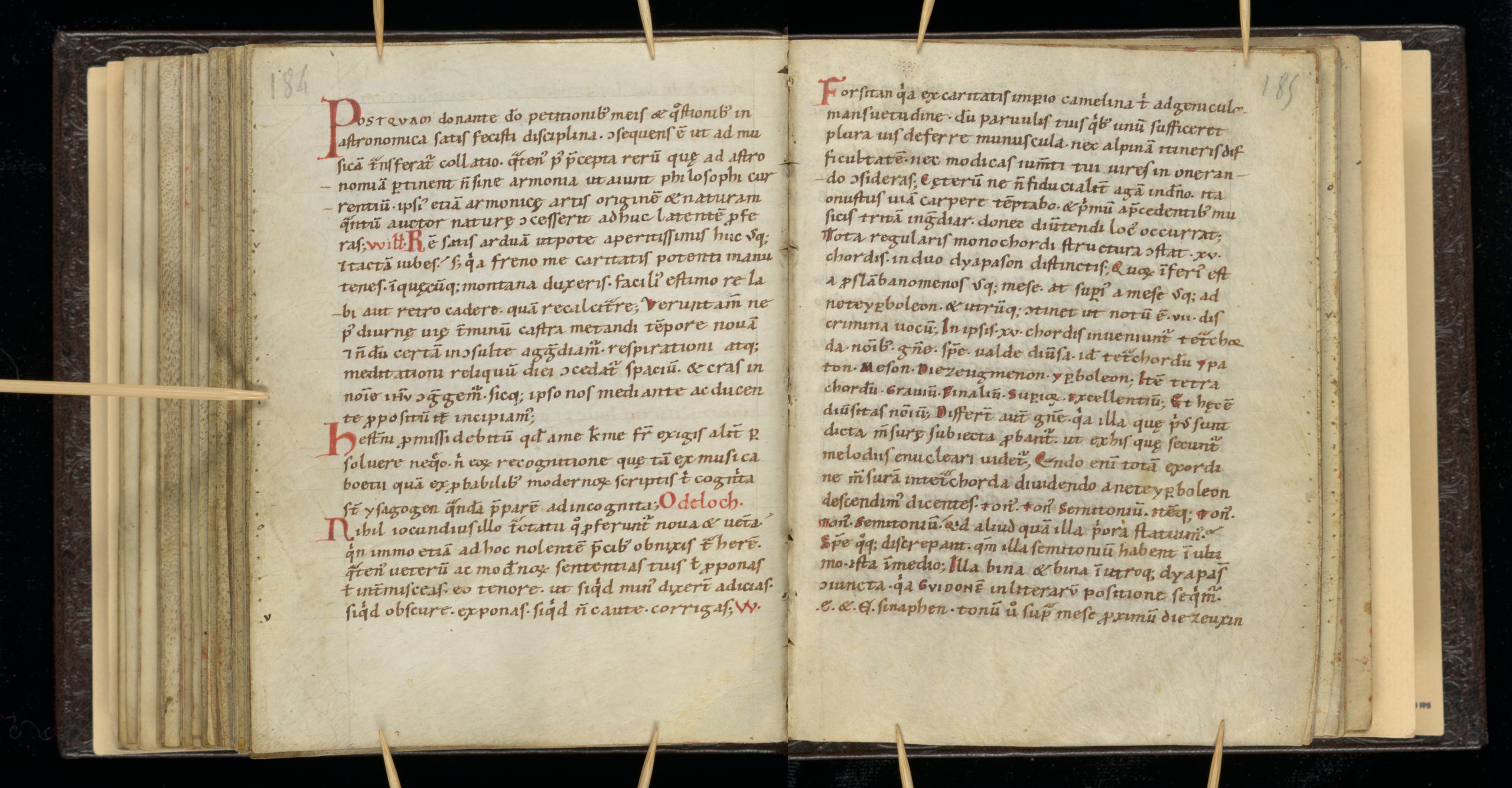

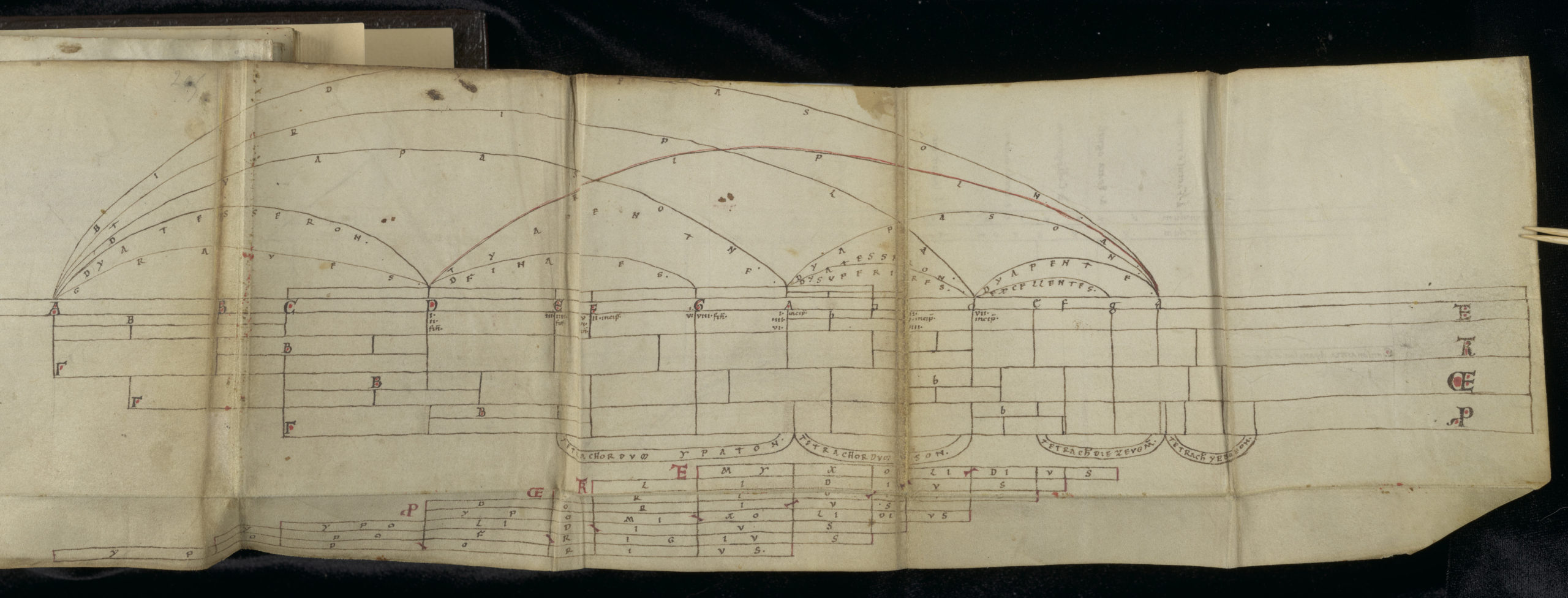

Hermann’s principal topic in Musica is the modes, but the treatise also includes noteworthy discussions of the monochord, the tetrachords, and the system of consonances (i.e., diatessarons, diapentes, and diapasons, with their species). (See Snyder’s introduction for a more comprehensive summary of the treatise’s content.) Notably, the Rochester Codex also contains at least two of his verses, both didactic interval songs, namely E voces unisonas (page 177) and Ter tria iunctorum sunt (page 180).[5] Hermann created these two verses to train musicians on applying a unique system of interval notation he had created that used both Greek and Roman letters. In the Rochester Codex, the text of Hermann’s verse E voces unisonas, labeled in red ink as “Cantil. H de VIIII intervallis” [Cantilena Hermanni de IX intervallis], has been annotated with neumes by a later hand.

8

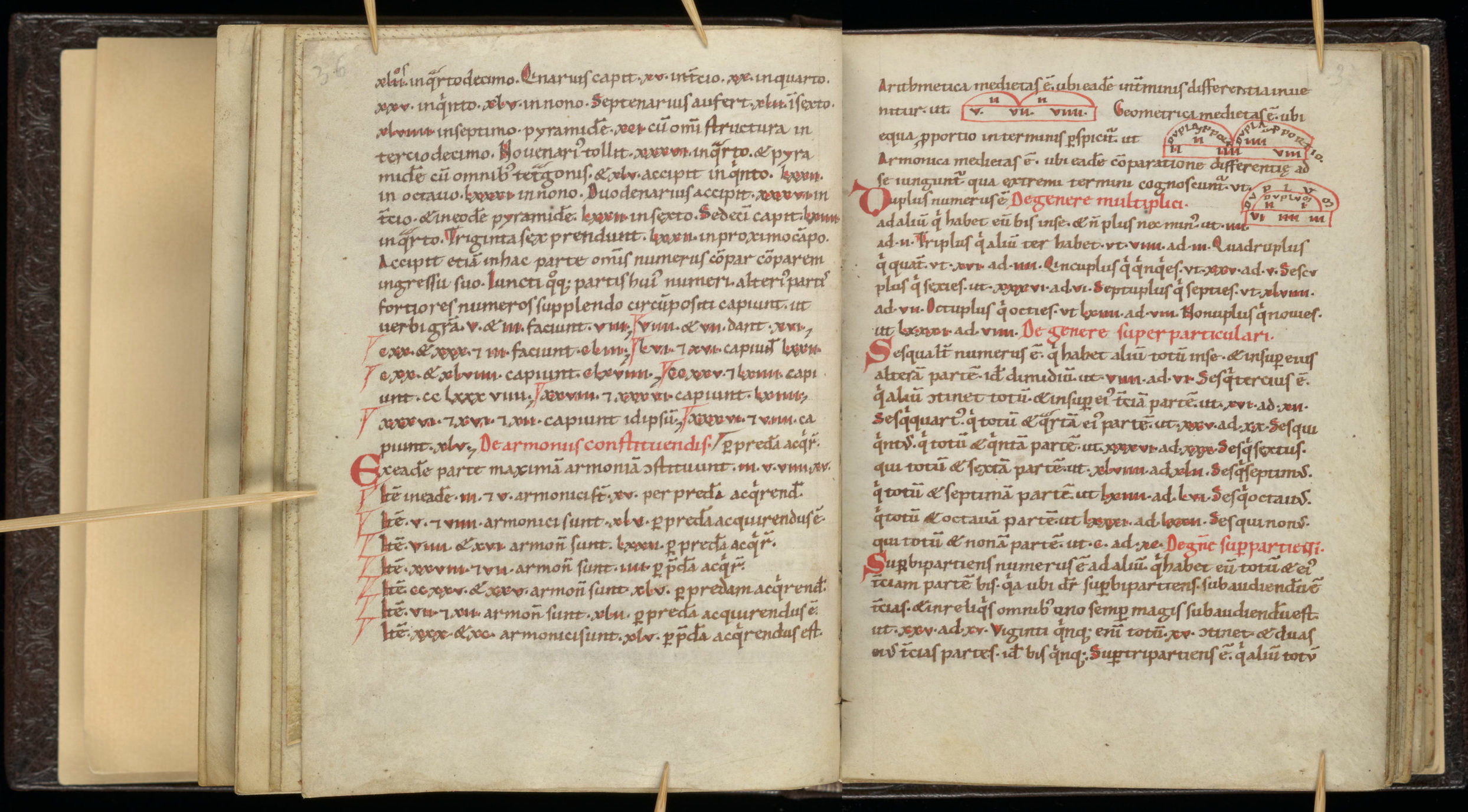

As previously mentioned, in the Rochester Codex, Hermann’s Musica is complemented by additional treatises on music by three other 11th-century German scholars, namely Wilhelm of Hirsau (d. 1091), Frutolf of Michelsberg (d. 1103), and Bern of Reichenau (d. 1048).

Wilhelm of Hirsau (in Latin Willihelmus Hirsaugiensis) (b. ca. 1026, Bavaria; d. July 2, 1091, Würtemberg, Swabia) was a German cleric, abbot, and monastic reformer. He is specifically remembered as the principal German advocate of the clerical reforms initiated by Pope Gregory VII (i.e., the Gregorian Reforms, ca. 1051–1080), and the monastic reforms he outlined in his Hirsau Constitution (in Latin Constitutiones Hirsaugienses) (1079) spread to Benedictine monasteries across the entire German-speaking region.

Wilhelm was born into the monastic life, having been promised by his parents to Saint Emmeram’s Abbey in Regensburg, Bavaria (modern-day southeastern Germany), following the medieval practice of child oblation. At St. Emmeram’s monastic school, Wilhelm received a comprehensive education, including extensive study of the medieval quadrivium: arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy. He wrote two influential treatises—one on astronomy, De astronomia, and a second on music, titled Dialogi de musica—both in dialogue form.

The Rochester Codex contains Wilhelm’s Dialogi de musica (pages 184–230), which is structured as a dialogue with his teacher, Otloh of St. Emmeram (ca. 1010–ca. 1072). Wilhelm’s principal topics in the treatise include the species of intervals and the tetrachords, the relation of both to octave scales, and the eight church modes. In his discussion of several of these and related topics, Wilhelm references or quotes passages from Hermann’s Musica directly.

9

Like Hermann, Frutolf of Michelsberg (in Latin Frutolfus Michelsbergensis or Frutolfus Bambergensis) (b. mid-11th century, Bavaria; d. January 17, 1103, Michelsberg), was a chronicler and scholar. His universal or world chronicle, which he compiled from more than 70 different sources primarily from the library at Bamberg Cathedral, is considered to be among the most complete and best-organized histories of the early Middle Ages. (After Frutolf’s death, his Chronica was edited and extended by other monks at the Michelsberg Abbey.)

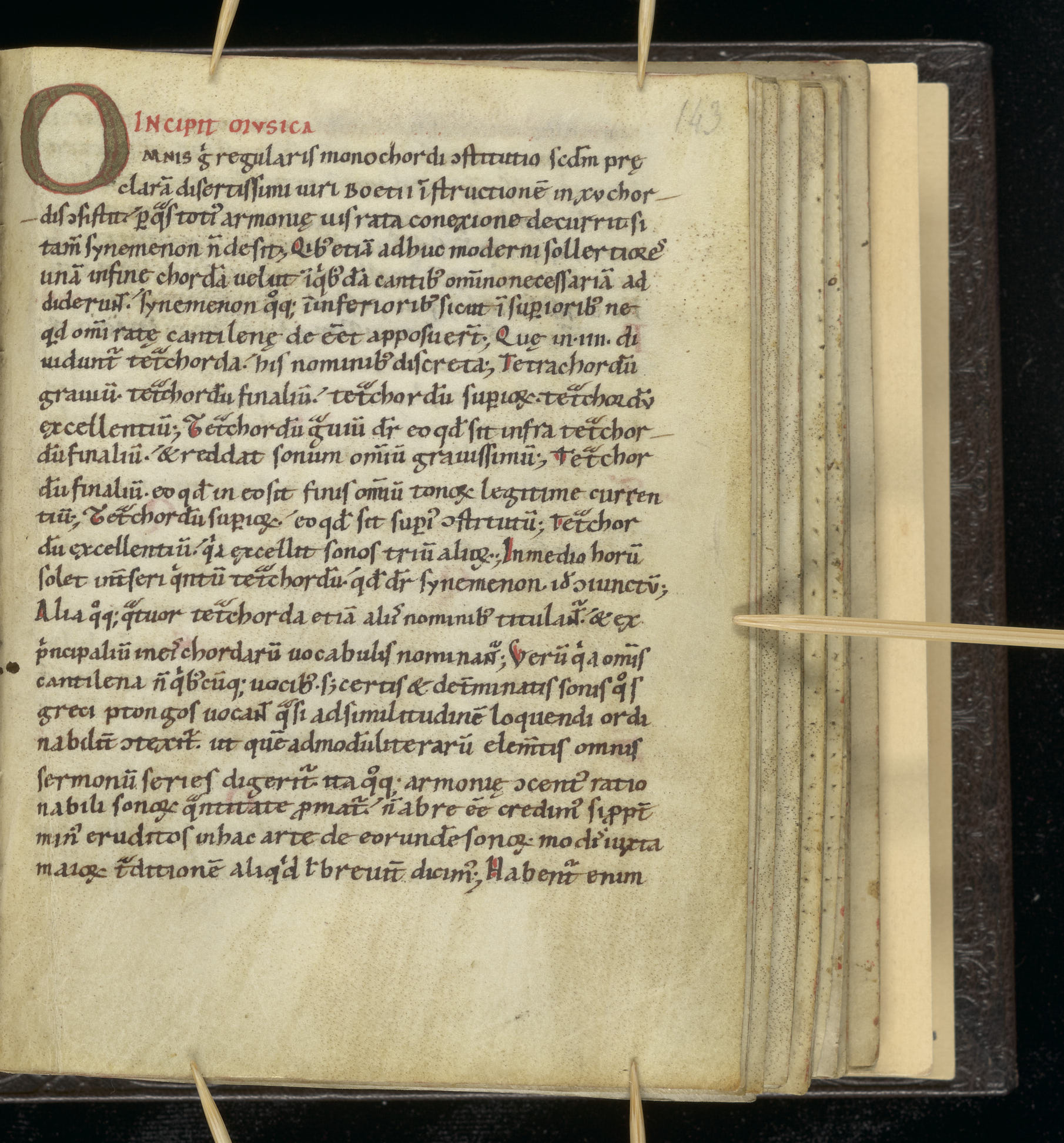

Frutolf is represented in the Rochester Codex in excerpts from his Breviarium de musica et tonarius (pages 173–183). His Breviarium is a treatise on music in the south German theoretical tradition and, like his Chronica, is largely a compilation of material from other treatises on music. The principal topics covered are the origins and names of the pitches (after Boethius), the monochord, the proportions that govern consonances, the tetrachords, and the ecclesiastical modes and their intervals. In his Tonarius (or Tonary), Frutolf provides a list of pieces from the chant repertoire, including sequences from the Mass, which he classifies according to the eight psalm tones. Frufolf’s tonary is deeply indebted to that of Bern of Reichenau (d. 1048), such that it has been described as an emended version of Bern’s work.

10

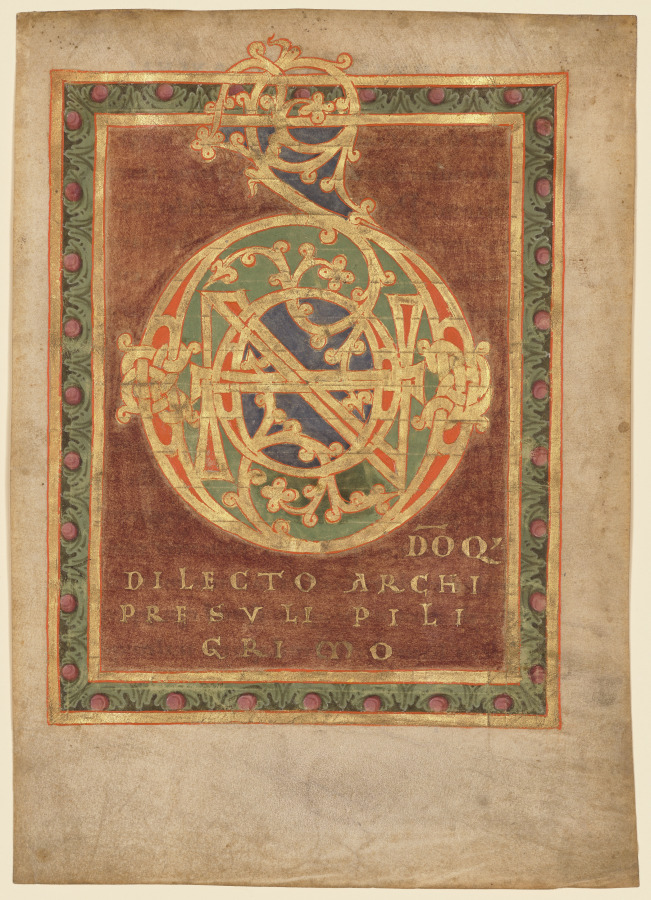

Bern of Reichenau (in Latin Berno Augiensis or Bernardus) (b. ca. 978; d. June 7, 1048, Reichenau) served as abbot of Reichenau monastery from 1008 until his death in 1048. He was also a music scholar, composer, and poet, with his chief work on music being a tonary that contains an extensive prologue (Prologus in tonarium, ca. 1021–1036). Like Frutolf’s tonary, Bern’s is likely also a compilation from earlier sources.

The Rochester Codex contains Bern’s Prologus (pages 143–173). Despite being presented as an introduction to his tonary, the prologue is comparable to other music treatises of the time in its content, including the scope of topics covered, and length. The primary subjects Bern covers overlap with those of the other treatises in the Rochester Codex, being the principal topics of discussion in 11th-century German speculative music theory: the tetrachords; the intervals, the species of the perfect consonances, and the eight ecclesiastical modes and their ranges. The Rochester Codex also contains an anonymous tonary (pages 131–142) that Ellinwood ascribed to Bern as its organization appears to be similar to that of Bern’s tonary. However, modern evaluation disagrees with Ellinwood’s attribution as the content of the tonary in the codex differs significantly from complete versions.[6]

11

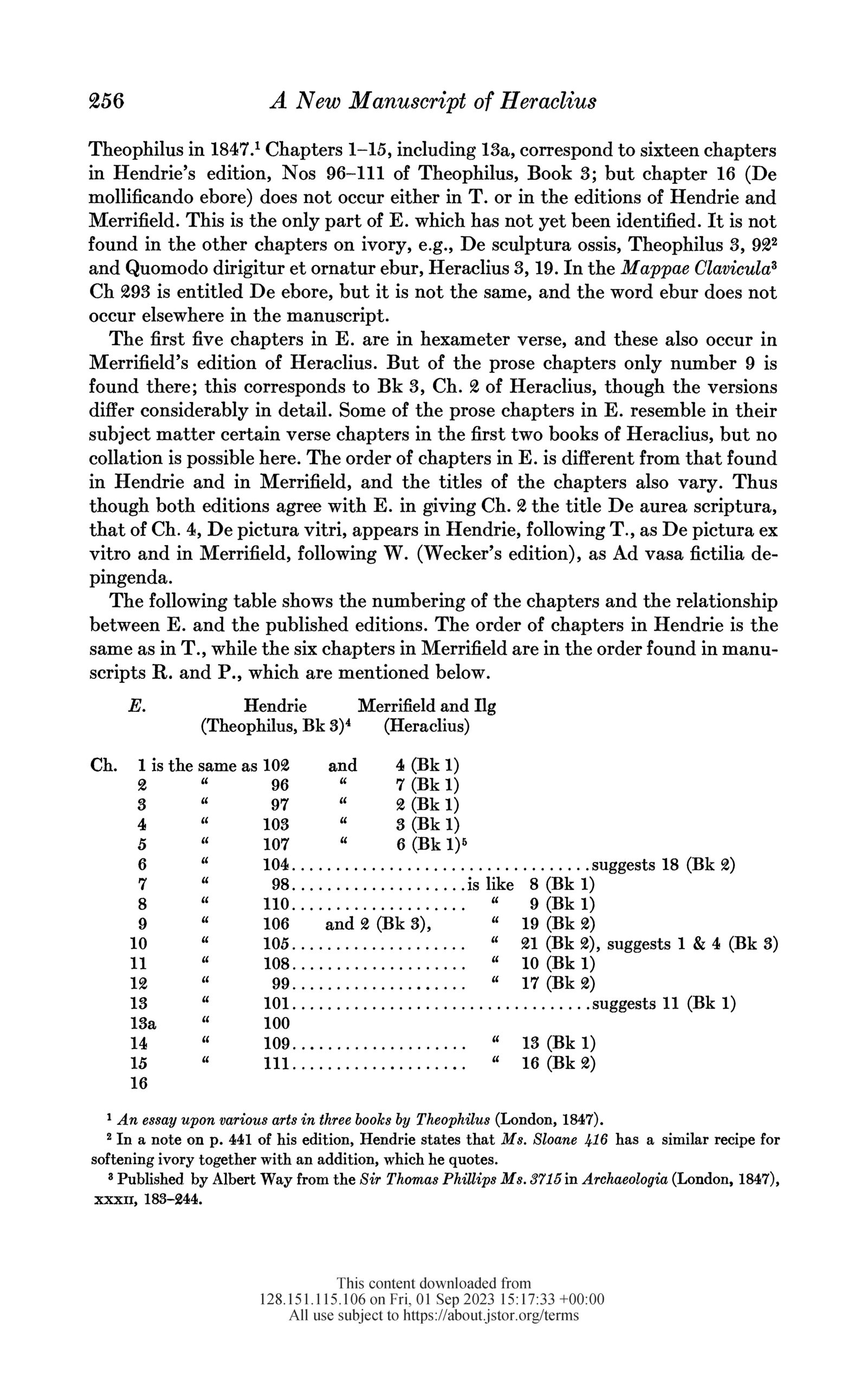

Within the Rochester Codex, the four aforementioned music treatises are interspersed with additional content on the other subjects of the quadrivium—particularly anonymous treatises and charts on astronomy and arithmetic. One of the most substantive of these other works—and a noteworthy treatise in its own right—is a series of six pages of medieval recipes for stained glass and iron work written in hexameter verse (pages 50–55). Given their unique verse form, the pages are easily identified an excerpt from Books I and II of the treatise De coloribus et artibus romanorum (On the colors and arts of the Romans), one of the few surviving treatises on art technology from the early medieval period. Modern scholarship has dated Books I and II, which comprise its original text, to sometime between the 7th and 12th centuries, with most dating it to the 10th century; Book III, which unlike the earlier portion is written in prose, was a later addition, likely added during the 12th and 13th centuries. Little is known about the author of the earlier books, who is cited as Heraclius (or Eraclius; possibly a pseudonym), but it is assumed that they were likely a native of Italy or a northerner who had gained substantial knowledge about Roman artistic customs.

Most of the surviving manuscripts that contain De coloribus date from the 13th century or later, with the two most complete copies being preserved in a 13th-century German manuscript now housed at the British Library in London (Egerton MS. 840 A) and in a French manuscript written in 1431 (Paris, Bibliothéque National, MS. Lat. 6741). Accordingly, the inclusion of several verses from De coloribus in the Rochester Codex was significant as, at the time of its purchase by SML, it was the earliest manuscript known to contain some part of the treatise—predating other copies by at least 100 years. The first modern edition of the treatise was produced in the 1840s by Mary Merrifield, who had been commissioned by the British government to collect and translate Italian manuscripts relating to the early history of medieval and renaissance painting (Original Treatises on the Arts of Painting, 2 vols.). In 1940, John Chatterton Richards produced an edition of the verses contained in the Rochester Codex as part of an article for the journal Speculum.[7]

12

From the Rochester Codex’s arrival at SML in 1929, providing access to the codex and promoting scholarship on its contents have been priorities—with Dr. Ellinwood’s edition of Hermann’s Musica (1934/1936) and John Chatterton Richards’s article and transcription of the excerpts from De coloribus et artibus Romanorum (1940) as early examples. Barbara Duncan, in her May 3, 1930, letter to Dr. Johannes Wolf (reproduced at the beginning of this digital exhibit), noted SML’s plans to publish a translation of the codex. She also promised to send a “photostat copy” of the volume to Dr. Wolf, indicating that SML issued a reproduction of the codex, at least privately to Dr. Wolf, as early as the 1930s. In the 1960s, the codex was microfilmed and distributed widely to other libraries and scholars as part of SML’s Microform Service. In 2003, a preservation quality microfilm was produced of the codex, which provided higher-quality images of the volume’s pages than had been previously available, albeit only in black and white. A PDF of that microfilm was made freely available online in 2013 through UR Research, the University of Rochester’s institutional repository.

With the 2020 imaging of the codex at the University of Rochester’s Digitization Lab, high quality color images of the Rochester Codex are now available, providing even greater accessibility to the invaluable 11th-century manuscript. The photos above show Digitization Specialists Lisa Wright (pictured above in a black facemask) and Clara Auclair (pictured above in a yellow facemask), carefully preparing the codex on the Lab’s copy stand before imaging each page with the reprographic camera. The Lab’s equipment is ideal for imaging cultural heritage objects like the Rochester Codex, and its staff works regularly with River Campus Libraries and University of Rochester faculty and students on diverse projects that require different types of imaging needs (see, for example, the online resource for the ReEnvisioning Japan Collection and the Isabella Beecher Hooker Digital Collection). Sibley Music Library is grateful for their technical support in digitizing not only this codex but also a growing number of other rare treasures from SML’s rare books holdings and special collections.

Endnotes

[1] Albi Rosenthal, “Wolffheim, Werner,” Grove Music Online, 2001.

[2] Karl Preisendanz, quoted in Leonard Ellinwood, Musica Hermanni Contracti, Eastman School of Music Studies No. 2 (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester, 1936), 2. Call number: ML172 .E46H

[3] See John L. Snyder, “Introduction,” The Musica of Hermannus Contractus, edited and translated by Leonard Ellinwood (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2015), 47. Call number: MT5.5.H552 M987 2015

[4] Leonard Ellinwood, Musica Hermanni Contracti, Eastman School of Music Studies No. 2 (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester, 1936), 1. Call number: ML172 .E46H

[5] A third verse, Ter terni sunt modi (Rochester Codex, pages 176–177), was attributed to Hermann in earlier scholarship, but more recent work has suggested Wilhelm of Hirsau as the author.

[6] See John L. Snyder, “Introduction,” The Musica of Hermannus Contractus, edited and translated by Leonard Ellinwood (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2015), 44, n140. Call number: MT5.5.H552 M987 2015

[7] John Chatterton Richards, “A New Manuscript of Heraclius,” Speculum, vol. 15, no. 3 (July 1940): 255–271. Available via JSTOR.

Image Credits

Monastery and cloisters at Reichenau, photograph © Hilarmont (Kempten), CC BY-SA 3.0 DE, via Wikimedia Commons.

Map of Lake Constance (Bodensee), German Wikipedia, uploaded by user Tschubby, GNU-Lizenz für freie Dokumentation.

North façade of the Cathedral of Saint Stephen, Toulouse, photograph by Didier Descouens, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Detail from map of Europe and the Mediterranean Lands about 1190, from William R. Shepherd, The Historical Atlas (1926), in the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, University of Texas at Austin.

Drawing of Hermannus (i.e., Hermann of Reichenau) (at right, holding an astrolabe) with Euclid, from Oxford, Bodleian Libraries, MS GB-Ob Digby 46, folio 8v, CC-BY-NC 4.0.

Hermann of Reichenau, E voces unisonas with neumes. from Badische Landesbibliothek Karlsruhe, Cod. Karlsruhe 504, CC-BY-License (4.0).

Drawing of Wilhelm of Hirsau, from Reichenbacher Schenkungsbuch, Württembergische Landesbibliothek Stuttgart, Cod. hist. 4° 147, page 4.

Dedication page from Bern of Reichenau’s tonary, Cleveland Museum of Art, Creative Commons Zero.

Transcription of E voces unisonas in modern staff notation, from Leonard Ellinwood, Musica Hermanni Contracti, Eastman School of Music Studies No. 2 (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester, 1936), 11. Call number ML172 .E46H

Audio Excerpts

The Miracle of the Century (the ensemble Ordo Virtutum performs music by Hermann of Reichenau). Call number: CD 30,262

Insula Felix: Music from Reichenau, the Island Monatery (Ordo Virtutum with Stefan Morent, conductor). Streaming audio available via NAXOS.

More from Sibley

Codex saeculi XI [Rochester Codex]. Call number: ML92 1100

Musica [Facsimiles of the 12th-century Vienna Codex #51, fol. 82r–90r]. Call number: M171.H552

Musica Hermanni Contracti, by Leonard Ellinwood. Call number: ML172 .E46H

The Musica of Hermannus Contractus, edited and revised by John L. Snyder. Call number: MT5.5.H552 M987 2015

External Links

The Codex and Crafts in Late Antiquity, exhibition held at the Bard Graduate Center (February–July 2018).

Book Illuminations from the Reichenau Monatery, Münchener DigitalisierungsZentrum Digitale Bibliothek [digital collection].

1300 Jahre Reichenau [website, in German, celebrating the 1300th anniversary of the founding of the Reichenau monastery, 2024].

For further information, please inquire at the Ruth T. Watanabe Special Collections department.