Published on May 16th, 2022

1955: Howard Hanson’s Merry Mount at the Festival of American Music

Sixty-seven years ago this week, on Monday and Tuesday, May 16th and 17th, 1955, Howard Hanson’s opera Merry Mount was produced at the Eastman School’s annual Festival of American Music. Howard Hanson had composed his only opera on a commission from the Metropolitan Opera Company, and apart from a one-night stand by the Met in the Eastman Theater in 1934, there had been no previous production of Merry Mount in Rochester. In fact, the 1955 Eastman production marked the first staged production of Merry Mount since the opera’s premiere at the Met. The performances of Merry Mount concluded the 1955 Festival of American Music, which was in itself a noteworthy occasion in that the 1955 Festival marked the 25th anniversary of the founding of the Festivals. Further, the performances of Merry Mount marked the re-opening of the Eastman Theater following a closure of several months due to a structural failure. (Several ceiling panels had collapsed, requiring a major servicing.) That Merry Mount did not make it into the active repertory is a striking omission in the career of a composer who was accustomed to his works being frequently performed during his professionally active years. Nevertheless,

The drama

The story of Merry Mount is set in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1625. The story runs concurrently on two separate but inter-twined levels: in the background, the conflict between an established settlement of Puritans and a band of Cavaliers newly arrived from England; in the foreground, the personal drama involving one man and his own internal conflicts. The action depicts at once the psychological-erotic drama of Wrestling Bradford, the Puritans’ preacher, is a man at war with himself, wrestling with longings that find no outlet, and that manifest themselves in dreams in which he perceives himself to be tempted by diabolical forces; and also the attempt by a band of Cavaliers newly arrived from England to found a colony of their own. They arrive bearing a warrant from King Charles giving them a grant to that particular strip of land, but it seems that the King had overlooked the fact that there was already a settlement of Puritans occupying the site. The Cavaliers, with their music, their jollity, and their unabashed acknowledgement of human emotions, observe a decidedly different way of life from the cheerless Puritans. The latter are horrified by the Cavaliers; one of their elders, Praise-God Tewke, goes so far as to invoke Divine wrath upon them—“Thou Lord of Heaven, Unseal the fountains of Thy wrath upon this generation of hellish vipers!”—and then tells the Cavaliers “in a voice of thunder,” “Enough, ye Sons of Darkness! Hark to my word: Cast off your ship, and get you home to England!” Nevertheless, it is the day of the Sabbath, and the two sides agree to a truce, deferring their differences until the next day. Act I ends with the Puritans resolving to “be lions of Jehovah And tear the flesh of unbelievers” while off-stage, the Cavaliers are proceeding with their worldly intentions and erecting a Maypole.

As Act II begins, the Cavaliers are engaged in their May Day festivities. The extensive stage directions outlining the festivities are a wonder to read: they conjure up a scene of riotous bacchanalia, an atmosphere wine and revelry abound, where up is down and down is up, and where opposing sides join together in harmony (the proverbial St. George and the Dragon walk about the stage arm in arm, for example). We might liken the scene to the song “The Lusty Month of May” in the musical Camelot by Lerner and Loewe. The Maypole scene is an extended episode featuring dancers on the stage. The Puritans, in their antagonism, break the truce and savagely attack the Cavaliers, taking them captive and toppling the Maypole. Wrestling Bradford, meanwhile, forms an attraction to one of the Cavalier women, Lady Marigold Sandys, who happens already to be engaged to Sir Gower Lackland (the May King in the Maypole scene). In the wake of the Puritans’ attack upon the Cavaliers, Marigold is taken captive and Sir Gower is killed. Bradford has a dream in which he swears his allegiance to the devil and places a destructive curse upon New England. When Bradford has awoken from his dream, he finds that the neighboring Native Americans (referred to as “Indians” in the published score), who had suffered the indignation of their land being misappropriated by the Puritans when the latter had arrived from England, have attacked the Puritans’ settlement and have set fire to it. At the opera’s conclusion, Bradford is under the influence of his dream-induced delusion and has fallen from grace in the eyes of his Puritan flock. He seizes Marigold and carries her into the raging flames—a murder-suicide—while the Puritans, surrounded by the flaming ruins of their village, kneel in desolate prayer as the curtain falls.

The antecedents, the commission, and the premiere

The story as depicted in the opera has antecedents in historical fact and in literature. First, it is established that in the 1620s, a group of Cavaliers landed from England and established a settlement that became known as Mount Wollaston (on the site of what is today the town of Quincy, Massachusetts). Their leader, Thomas Morton, proclaimed the place “Merry Mount” by name and commanded that a Maypole be set up as the site for dancing and acting out May Day jollity, thereby earning the wrath of the local Puritans. The governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, John Endecott, intervened and ordered that the maypole be cut down. John Morton, as the accused ringleader, was severely punished and was banished to England. (In the opera, Thomas Morton appears as the uncle of the leading soprano, Lady Marigold Sandys.)

The contract between the Metropolitan Opera Company and Howard Hanson for a new opera, enacted on May 3rd. 1933. Note that the document was created by no more illustrious means than being typed on two pages of paper from a standard legal pad.

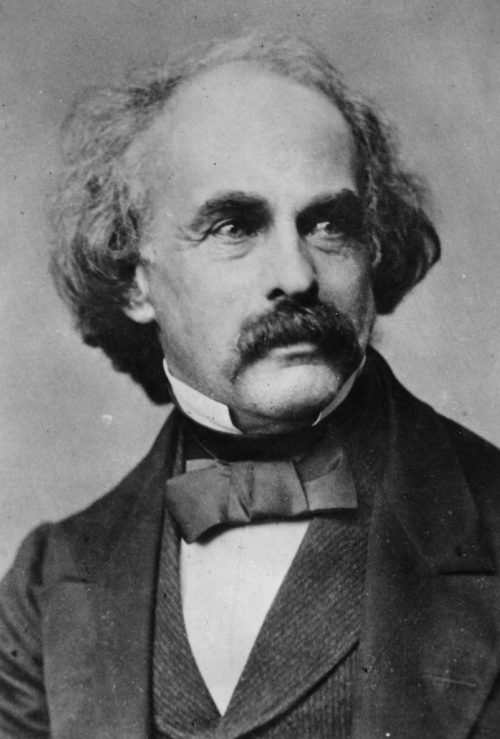

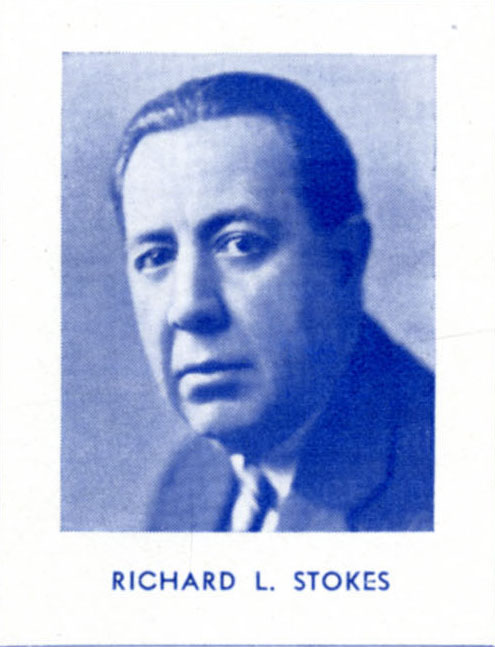

That particular Maypole event was used by Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864) in his short story “The May-Pole of Merry Mount” which was published in Hawthorne’s Twice-Told Tales (first volume, 1837). Hawthorne added his own layer of detail to the story, no doubt for literary and dramatic purposes. Then, nearly a full century later, writer and critic Richard L. Stokes (1882-1957) used Hawthorne’s tale as his point of departure for a book-length poem that the Metropolitan Opera Company had commissioned, the poem to serve as the libretto of a new opera. Having accepted the Met’s commission, Stokes undertook extensive research on the history of Puritanism in the U.S., gaining insights that would greatly inform his completed poem. Stokes completed the poem in 1931, and in 1932 it was published by Farrar and Rinehart as “a dramatic poem for music in three acts of six scenes”. Stokes exercised a considerable degree of poetic license which he himself took care to justify, both in his preface to the publication and in statements published after the opera’s premiere performance.[1]

At this juncture, enter Howard Hanson. As Hanson would later recount, he was nominated by no fewer than three music critics to receive the Met’s commission to compose the music to Stokes’ poem.[2] Up to this time Hanson had composed mainly orchestral music and choral music, but he was favorably challenged by the musical and dramatic possibilities posed by Stokes’ poem, and he readily accepted the commission. Hanson worked on his opera throughout 1931-32, somehow finding the time to compose while holding down his administrative day job. He would later recount this time management challenge in his Autobiography, writing “. . . I became more than ever a midnight composer . . .” on grounds that he had mostly worked on the opera between the hours of eleven P.M. and two A.M..[3] However daunting the challenge may have been, Howard Hanson was never one to agonize over anything. He was fired to his task, and he was, as always, supremely confident of his own abilities.

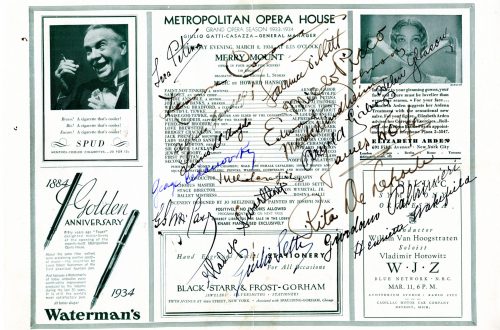

Further to the unfolding production work, only a small number of communications are extant today that indicate any of the specifics; these all come from the Howard Hanson Collection, manifest in Hanson’s correspondence with librettist Stokes and with baritone Lawrence Tibbett, who would play Wrestling Bradford in the premiere at the Met. Along the way to the premiere, the Metropolitan Opera Company granted permission for a concert performance that would precede the Met’s staged production; the concert performance took place at the University of Michigan’s annual May Festival in Ann Arbor, Michigan on May 20th, 1933. The opera’s premiere at the Met was a matinee performance on February 10th, 1934, which was broadcast live via the NBC national radio network; the broadcast was picked up in Rochester, New York by radio station WHAM. There were six more performances at the Met, followed by three run-out performances in Brooklyn, Philadelphia, and Rochester. A scheduled performance in Boston was cancelled after some local protest, the Bostonians having incorrectly perceived a slight of their esteemed local ancestor William Bradford, first governor of the Plymouth Colony.

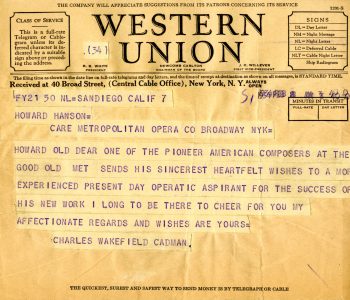

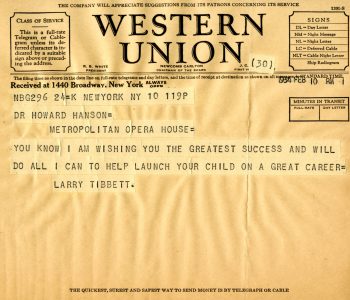

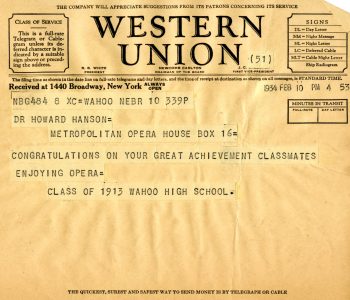

While the matinee performance of Merry Mount was in progress on February 10th, 1934, listeners in numerous places across the nation were registering their approval by means of telegrams sent to Howard Hanson. To cite three examples, these telegrams were sent by composers Charles Wakefield Cadman (1881-1946), himself a composer of operas; baritone Lawrence Tibbett (1896-1960), who sang the role of Wrestling Bradford in the premiere); and Hanson’s classmates from Wahoo High School, Class of 1913.

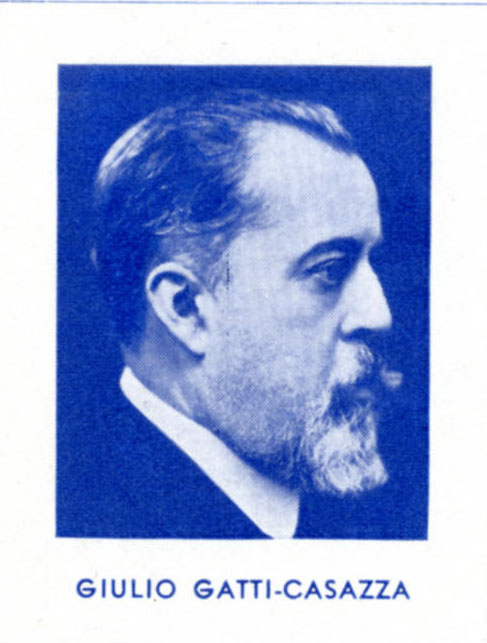

As is amply indicated from the New York press reviews preserved in Howard Hanson’s pressbooks, the premiere performance of Merry Mount was greeted with rapturous applause and with numerous curtain calls. Nevertheless, the Met did not retain Merry Mount in its active repertory. Hanson would later recount in his Autobiography that the Metropolitan Opera Company’s impetus for producing American operas was lost in the wake of two unexpected occurrences. First, General Manager Gatti-Cazassa suddenly and unexpectedly resigned and returned to Italy; his successor, American basso Herbert Witherspoon, was an enthusiast for American opera but died of a heart attack shortly after his appointment. He was succeeded in turn by Canadian-born tenor Edward Johnson,[4] whose mandate was simply to keep the Met afloat and solvent in a time of continuing economic depression. Thus, there could be no possibility of producing any more new works at the Met for the foreseeable future; in the ensuing thirty years, fewer new American operas were produced at the Met than had been produced in the latter half-dozen years of Gatti-Cazassa’s administration.[5]

Faced with the prospect of his opera falling into obscurity, Hanson set about re-distributing its music in various guises. He fashioned a suite of instrumental music from some of the opera’s episodes and called it Merry Mount Suite (published for orchestra by Harms, 1938; and for concert band [without the May-pole Dances] by Carl Fischer). The Merry Mount Suite has enjoyed a modest life of its own, having been commercially recorded and having occasionally been performed in concert halls.[6] However, the Suite is not musically representative of the opera at large, retaining as it does only the opera’s more animated passages, and omitting the generally cheerless episodes. Further, the “Maypole Dances”—the opera’s only explicitly joyous movement—were withheld from the band version. Hanson also made a “radio version” which has had one known performance (at the 17th Annual Festival of American Music, Eastman School of Music on May 3rd, 1947). The performing forces were the Eastman-Rochester Symphony Orchestra, the Eastman School Chorus, and selected vocal soloists, all under Hanson’s baton. The radio version performance was broadcast under the auspices of NBC’s “Orchestras of the Nation” series. The radio version represented an extensively abridged version; the one and only performance lasted just over one hour. Finally, it remains that certain vocal numbers from the opera have been performed in isolation on recital programs here and there; the Howard Hanson Collection contains printed programs from several such. Specifically, these have been the arias “Oh, ‘tis an earth defiled” (Bradford) and “No witch am I” (Marigold), the love duet between Bradford and Astoreth, and the chorus “It is the house of gay carouse”.

Altogether, Merry Mount has been staged no more than a half-dozen times: The Met, 1934; Rochester, 1955; San Antonio, 1964; Chautauqua, 1974; and Rochester, 1976. The 1974 Chautauqua production was based on a revision undertaken by Hanson and his Director, Leonard Treash, so as to render the work tighter and more intimate. The opera has also been presented in concert version on several occasions, including Ann Arbor, 1933; Southern Methodist University, 1952; Seattle, 2007; and Rochester, 2014. (The Rochester performance was immediately followed up by a run-out performance by the same performing forces at Carnegie Hall in New York City.) When writing his Autobiography in the 1960s, Hanson praised the San Antonio production in generous terms, naming each of the principals and several members of the production team, and going so far as to write, “And so I felt that in San Antonio, Texas, about thirty years after its premiere, Merry Mount was finally properly presented and heard.”[7] Curiously, Hanson did not happen to mention the 1955 Eastman production in his Autobiography, which is a disappointment. Eastman Opera was flourishing under the artistic direction of Leonard Treash, and it is doubtful that the artistic values of the production—the singing, the acting, the dancing, and the orchestral playing—could have been in any way lacking. Hanson could have afforded to be gracious towards the many who had participated in bringing his opera back to the stage.

The 1955 Eastman School of Music production

No documentation is extant indicating exactly when the decision was taken to produce Merry Mount at Eastman in 1955, but it seems certain that Hanson would have desired a showpiece for the 1955 Festival of American Music, marking as it did the 25th anniversary of the founding of the Festivals. Moreover, the opportunity to showcase the newly repaired Eastman Theater would have invited a gala performance of some kind. Hanson had perennially used the Festivals to feature Eastman School-affiliated composers, and he had not been modest about programming his own works in the Festivals and also in the American Composers Concerts. It remains true that performance of the opera under the auspices of the annual Festival of American Music would imbue the production with an innate institutional connection. Further, Hanson would be guaranteed a supportive audience, given that his reputation with the Rochester public had always been assured.

Formally, the 1955 performance was a production of the Eastman Opera Workshop, which, administratively and practically, was the forerunner of today’s Eastman Opera Theater. The production was under the direction of Leonard Treash; Howard Hanson conducted the Eastman School Symphony Orchestra. There were two performances, each having its own cast. For the May 16th performance, the role of Wrestling Bradford was sung by Eastman School alumnus Bernhardt Tiede; for the May 17th performance, that role was divided between two voice students, Max Shoaf and Richard Vogt. The printed program for the 1955 production contains many names well remembered today, both in the vocal corps and in the orchestra, as well as on the production team. (To name just two, John Beck, later a longtime Eastman School faculty member and Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra principal percussionist, was in the orchestra, and George Walker, pianist and later a Pulitzer Prize-winning composer, was one of the accompanists and vocal coaches.) Some notes that are among Hanson’s papers indicate the cuts that Hanson had approved in the score, all of which are borne out when listening to the recording of the production. So as to reduce the opera’s length to a manageable 90 minutes, many pages assigned to the chorus were eliminated, a move that would greatly anticipate the RPO concert version of 2014.

The printed program for the 1955 production contains many names well remembered today, both in the vocal corps and in the orchestra.

Both performances of the 1955 production were recorded, and they may be heard on CD service copies in the Sibley Music Library. When listening to the May 16th performance, one can hear Hanson’s reading aloud to the audience a congratulatory telegram that he had just received from “America’s most famous music-lover,” none other than President Dwight Eisenhower.[8] By the way, I have recently noted that one enthusiast out there has uploaded to YouTube.com a capture of the Met’s 1934 premiere of Merry Mount, complete with the announcer’s interjections and comments.

Numerous photographs from the 1955 Eastman production are extant, capturing representative moments in the drama. Many of the photos are attributed to Loulen Studio of Rochester, in which one of the two partners was the renowned Louis Ouzer (1912-2002), whose work needs no introduction here. Here follows a selection of these photos, with notes as to the accompanying action.

PHOTOS, ACT I

PHOTOS, ACT II, scene i

PHOTOS, ACT II, scene ii

PHOTOS, ACT II, scene iii

PHOTOS, ACT III

PHOTOS ACCOMPANYING THE PRODUCTION

[1] Mr. Stokes was obliged to write letters to several newspapers and other publications, including Musical America, responding to various criticisms, including the erroneous perception that Wrestling Bradford had been based on the real-time character of William Bradford, Governor of Plymouth Colony.

[2] The Autobiography of Howard Hanson / compiled and edited from manuscript sources by Vincent A. Lenti. Unpublished manuscript, p. 204. Eastman School of Music Archives.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Mr. Johnson had sung the role of Sir Gower Lackland in the Met’s premiere of Merry Mount.

[5] Ibid., pp. 213-214.

[6] Without citing each of them here, I notice that several renditions can be heard at www.youtube.com.

[7] Ibid., pp. 214-215. Note that Beverly Sills sang the role of Lady Marigold Sandys in the San Antonio production.

[8] Hanson’s pleasure at receiving the telegram would have been incalculable, given that he was a staunch admirer of Eisenhower. In 1969, after the former President’s death, Hanson wrote about his two meetings with Eisenhower for the Rochester press.

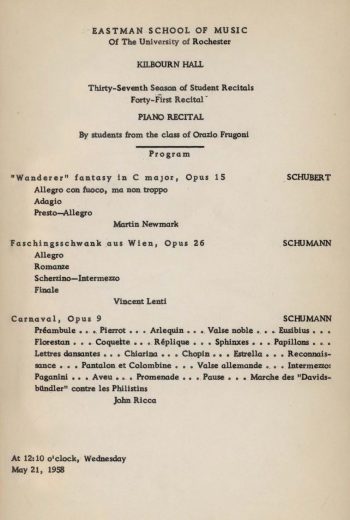

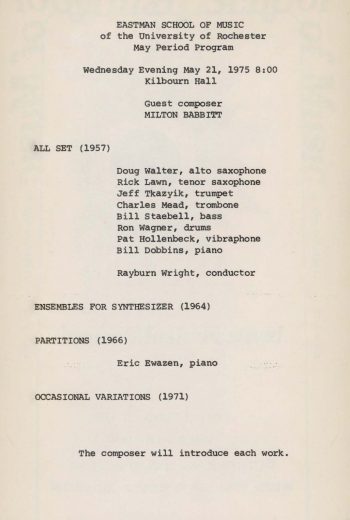

The Weekly Dozen

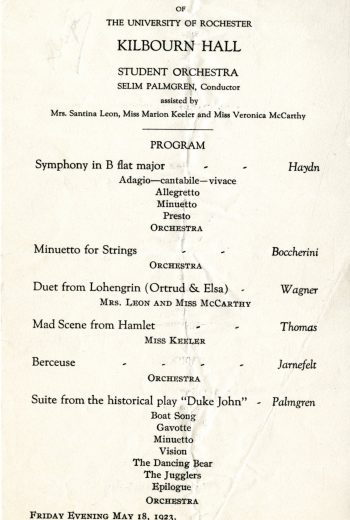

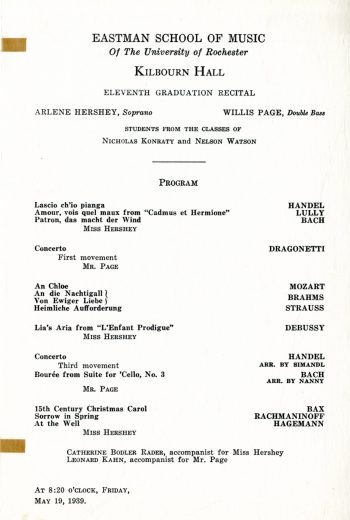

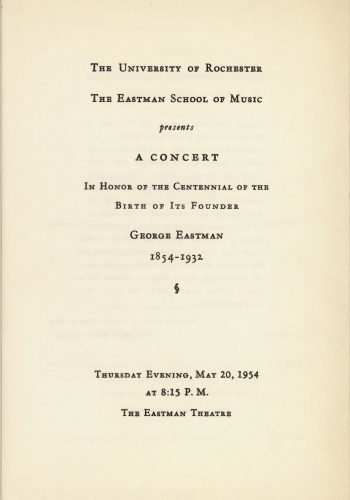

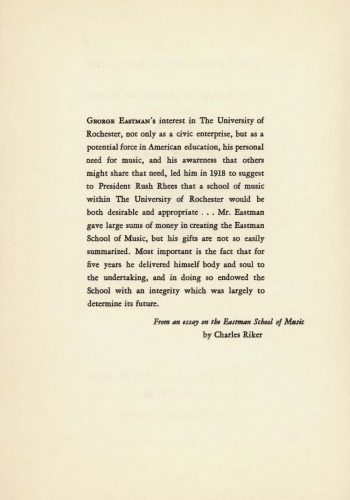

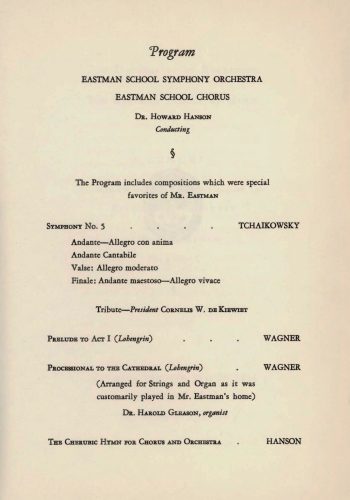

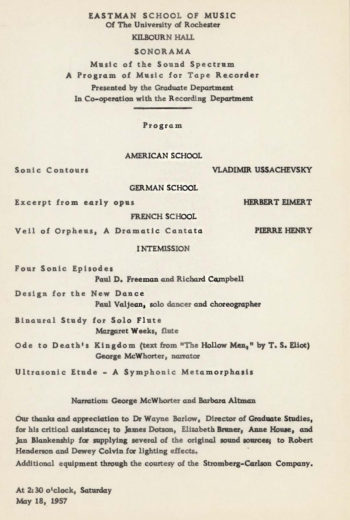

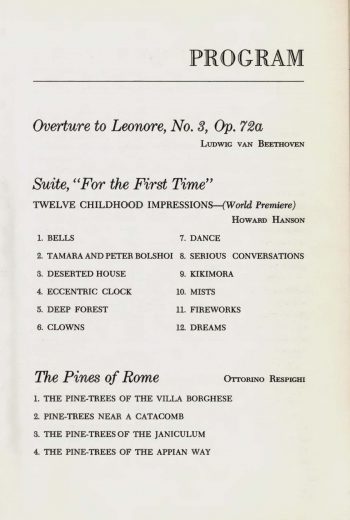

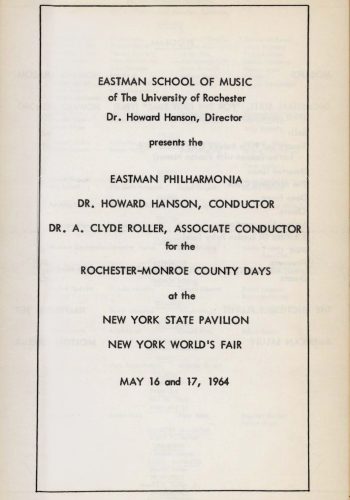

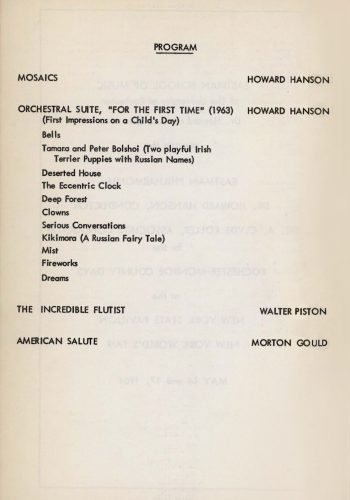

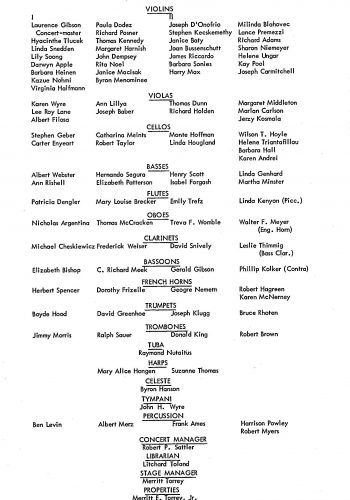

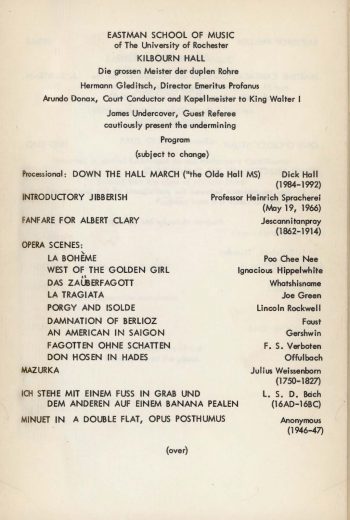

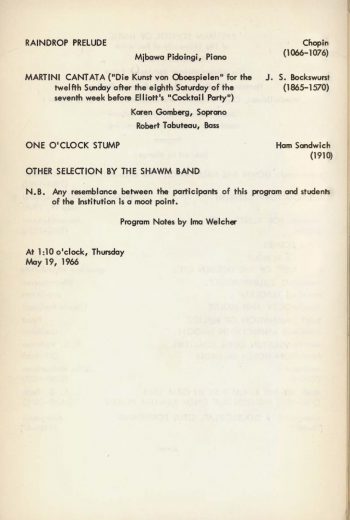

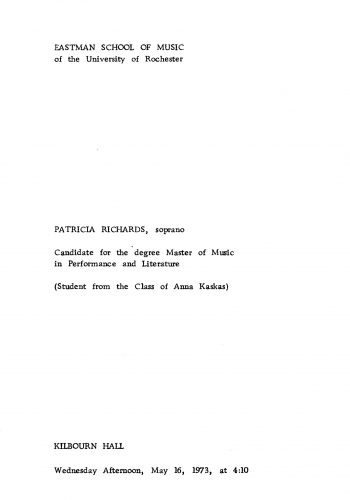

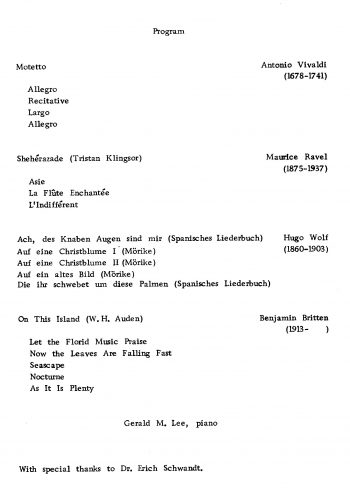

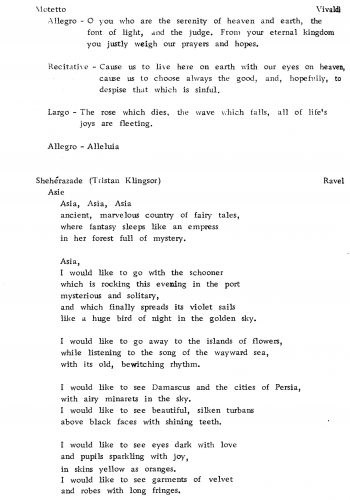

In this week’s “Weekly Dozen” we recognize one of the earliest concerts (1923) by the Student Orchestra (so called); a concert in honor of the centennial of the birth (1934) of the founder of the Eastman School of Music; the inauguration of a President of the University of Rochester (1963) whose administration would have far-reaching consequences for the Eastman School of Music; a concert given by the Eastman Philharmonia (1964) at the New York World’s Fair, which provided a fitting conclusion to the forty years’ service of Howard Hanson, who had founded the Eastman Philharmonia; a concert of some delightful jibberish (1966); a visit by Milton Babbitt (1975); and some superlative student performances such as grace the Eastman concert calendar each week of the semester.