Online exhibit from the Ruth T. Watanabe Special Collections; curated by Gail E. Lowther.

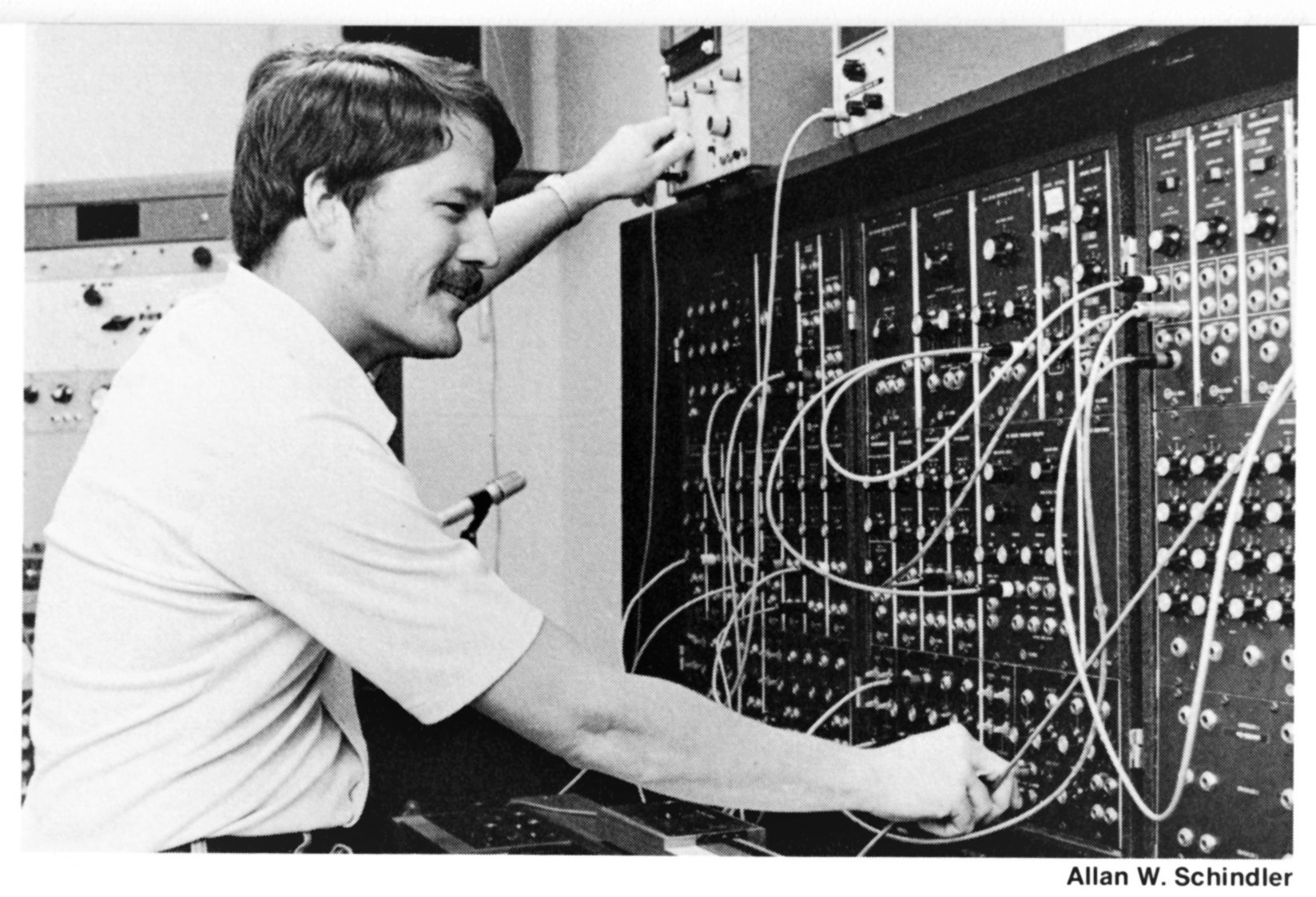

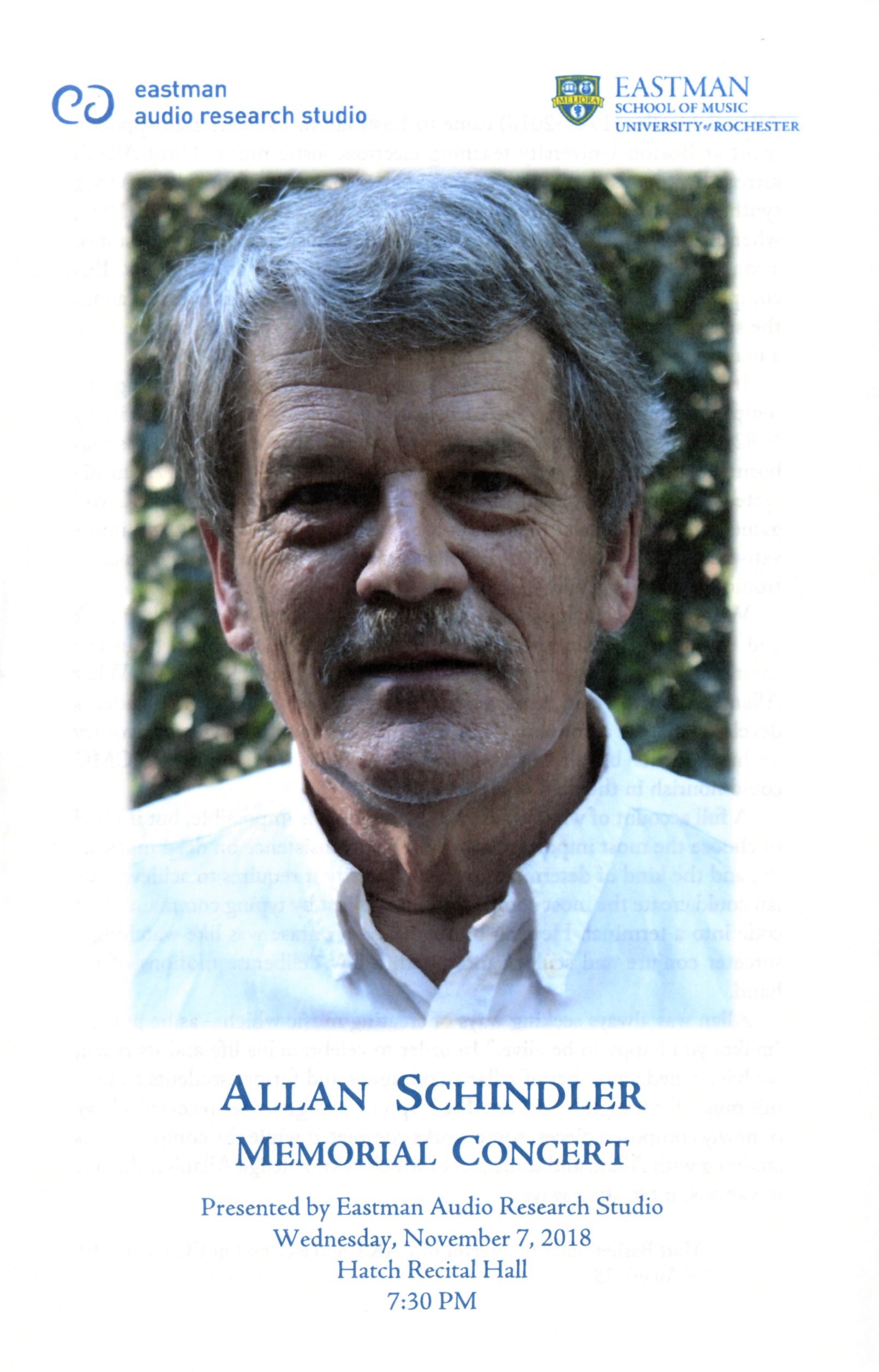

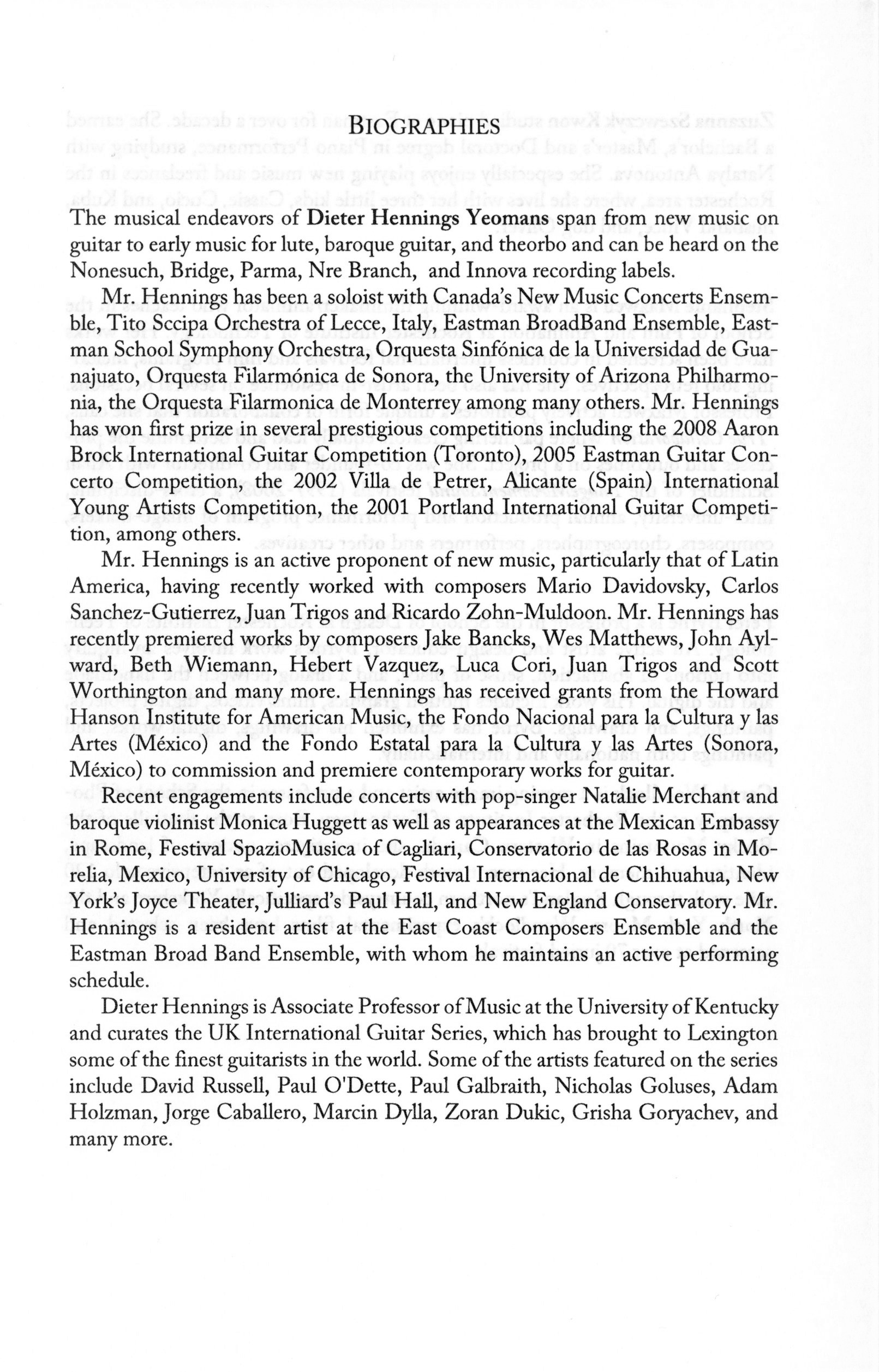

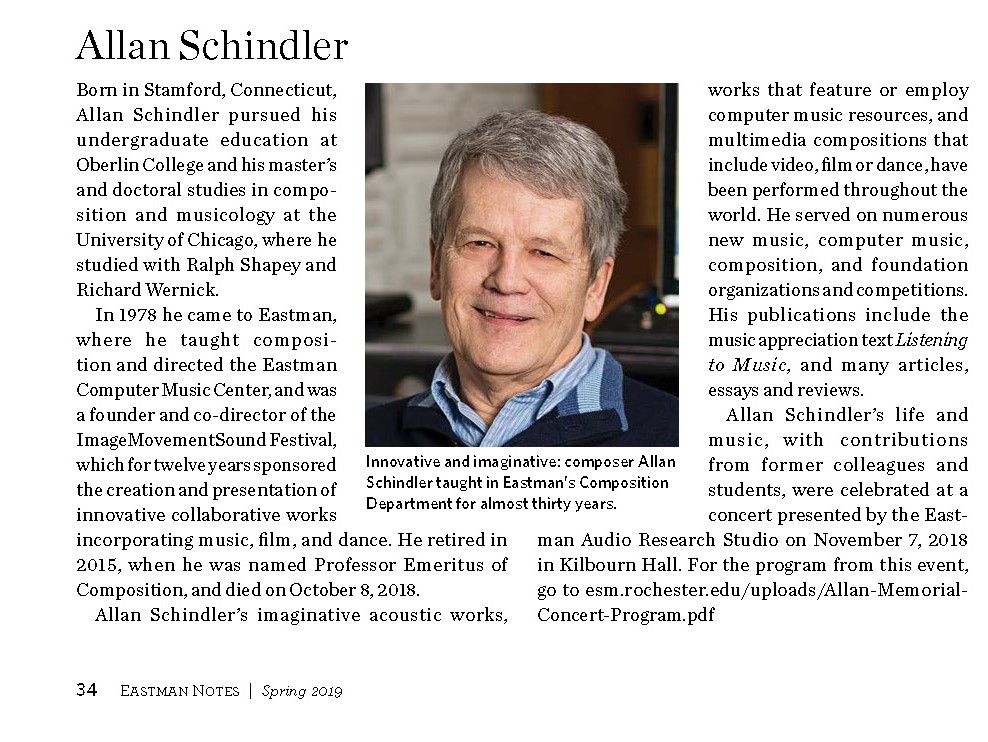

When Dr. Allan Schindler retired from the Eastman School of Music’s Composition Department in 2015, he left an indelible legacy. His students and colleagues knew him as a determined and thoughtful teacher, mentor, and composer who valued ingenuity, individual creativity, and—perhaps above all else—deep and sincere musicality. During his 38 years at Eastman, Schindler developed the Eastman Computer Music Center (ECMC), which he had founded shortly after joining Eastman’s faculty, into a versatile and creative center for computer music and multimedia collaborations with an international reputation for producing high quality and innovative projects. The foundation Schindler established at ECMC—with its emphasis on musical expression, creativity, and experimentation—has endured in its current successor, the Electroacoustic Music Studios @ Eastman (EMuSE), under the direction of Dr. Mikel Kuehn.

When Dr. Allan Schindler retired from the Eastman School of Music’s Composition Department in 2015, he left an indelible legacy. His students and colleagues knew him as a determined and thoughtful teacher, mentor, and composer who valued ingenuity, individual creativity, and—perhaps above all else—deep and sincere musicality. During his 38 years at Eastman, Schindler developed the Eastman Computer Music Center (ECMC), which he had founded shortly after joining Eastman’s faculty, into a versatile and creative center for computer music and multimedia collaborations with an international reputation for producing high quality and innovative projects. The foundation Schindler established at ECMC—with its emphasis on musical expression, creativity, and experimentation—has endured in its current successor, the Electroacoustic Music Studios @ Eastman (EMuSE), under the direction of Dr. Mikel Kuehn.

In 2019, shortly after Schindler’s death, the Sibley Music Library received the composer’s personal and professional papers and manuscripts. Newly processed as the Allan Schindler Collection, this archive of Schindler’s creative output and professional endeavors joins dozens of other archival collections of Eastman School of Music graduates and faculty members from the school’s Composition Department.

On the occasion of what would have been Dr. Schindler’s 80th birthday, we look back on his career and compositions in this digital exhibit, with documents and images taken from the Allan Schindler Collection and the Eastman School of Music Archive, to present a celebration of his life and lasting contributions as a composer, teacher, and musician.

On Display

1

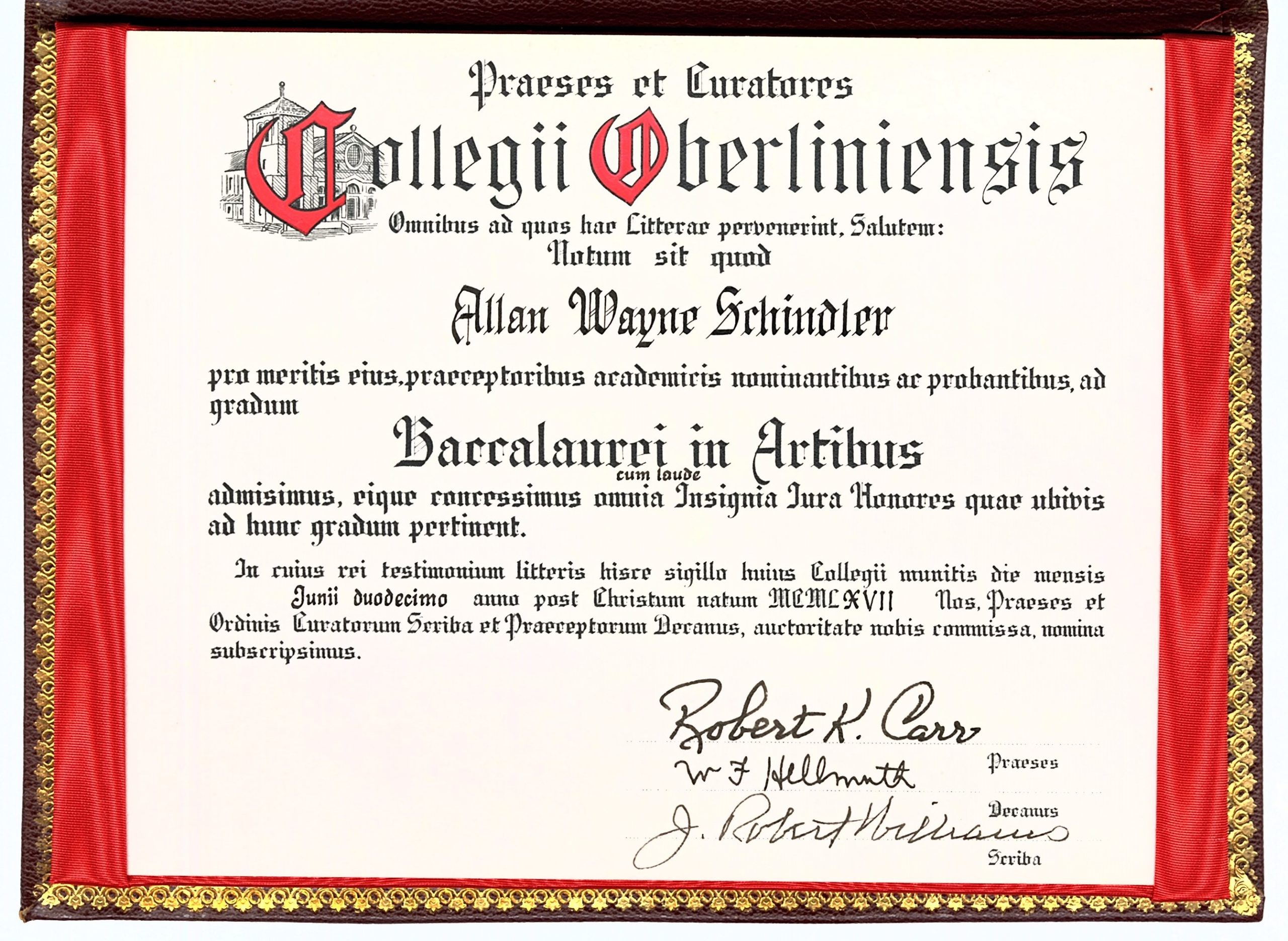

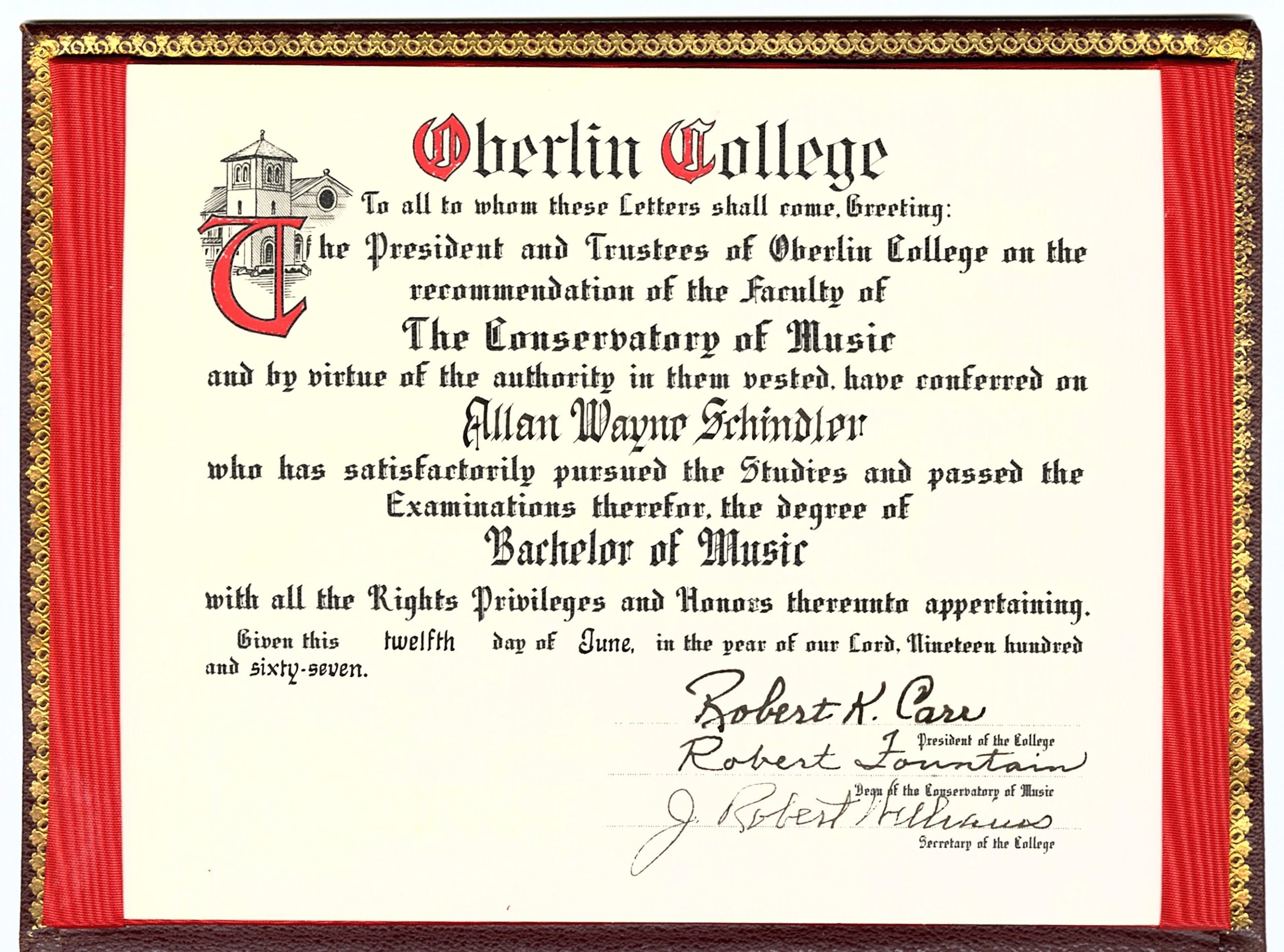

Schindler began his musical training at a young age, learning to play several instruments and studying woodwinds, piano, and theory at the Cleveland Institute of Music. Similarly, his interest in music composition was sparked early, and he wrote his first compositions at the age of 10. His early training in composition included studies in the Schillinger System of Composition with Bert Henry, a composer and applied mathematician who had studied with Joseph Schillinger personally and, for a time, operated the Schillinger Center of Cleveland as an authorized teacher of the Schillinger System. Additionally, while in high school and, later, as an undergraduate student at Oberlin College, Schindler worked as a freelance musician and arranger, playing with classical chamber ensembles as well as jazz and rock bands.

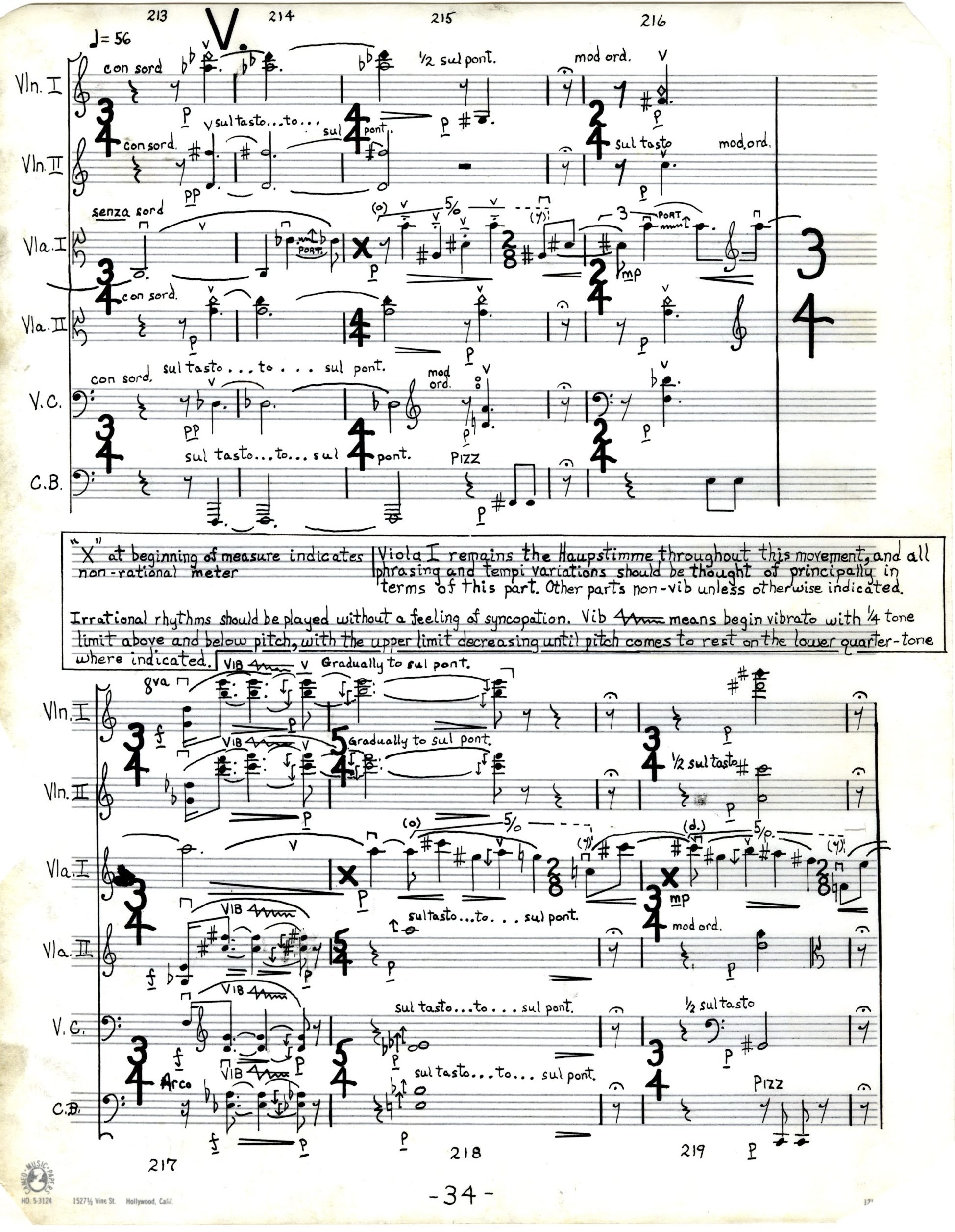

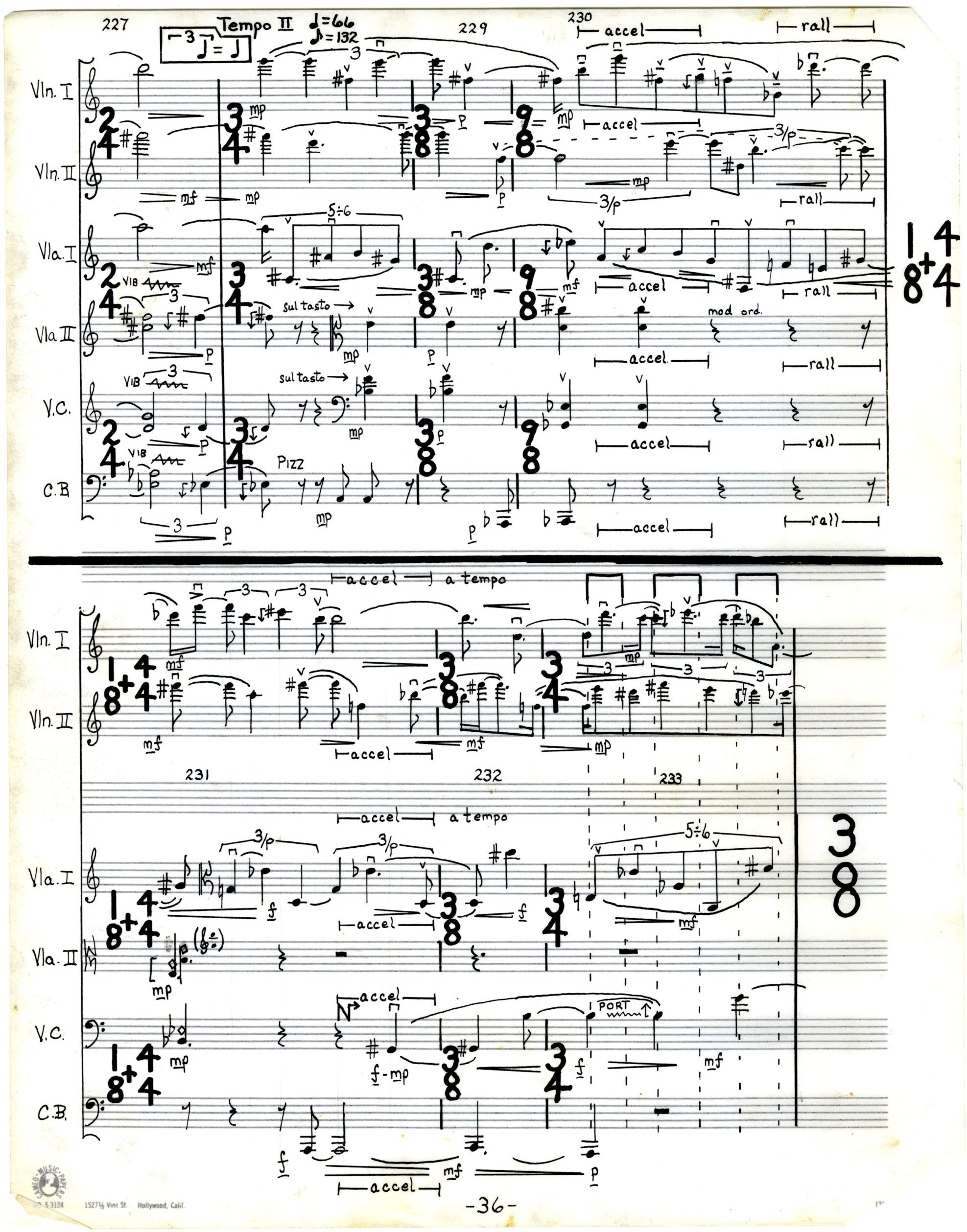

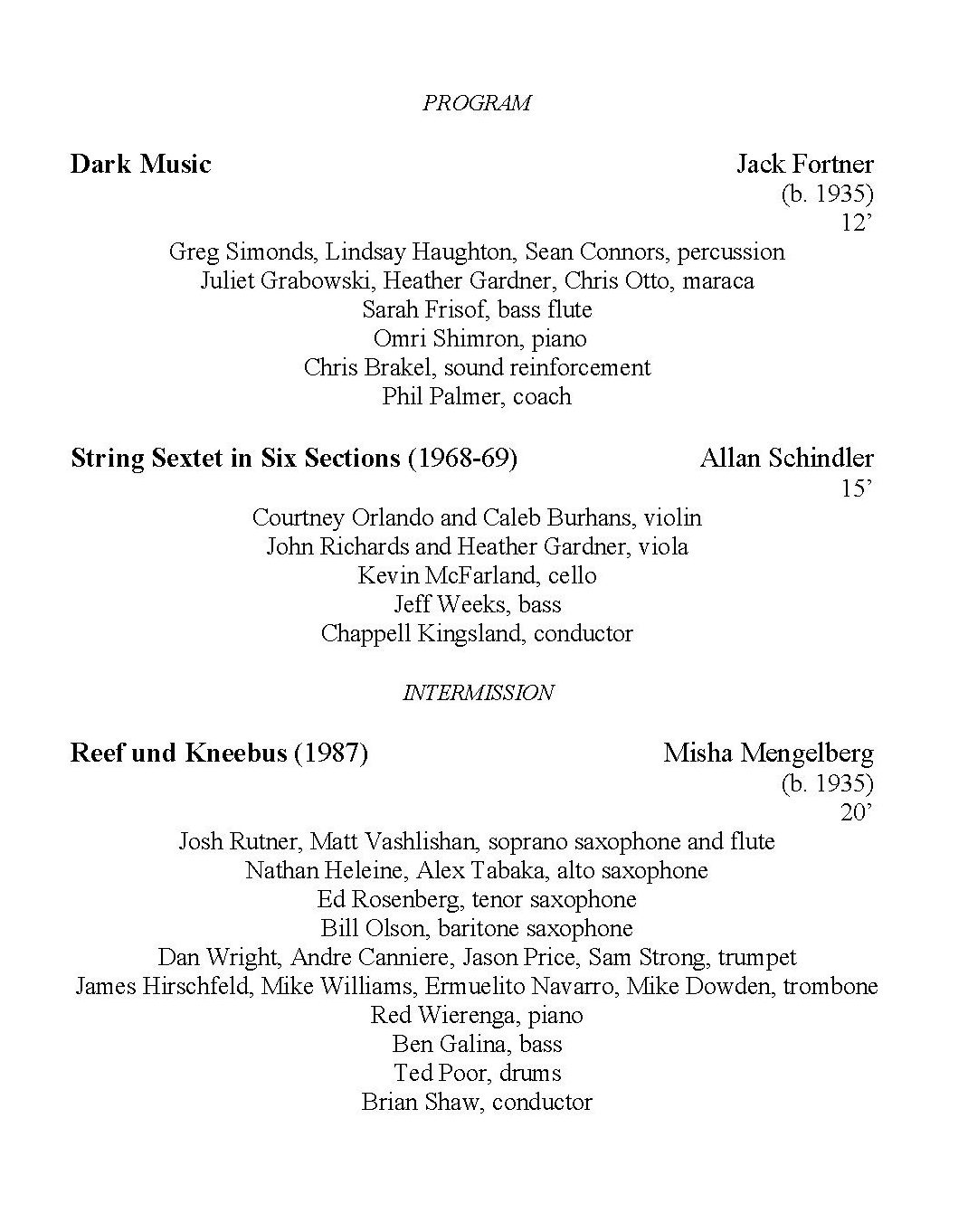

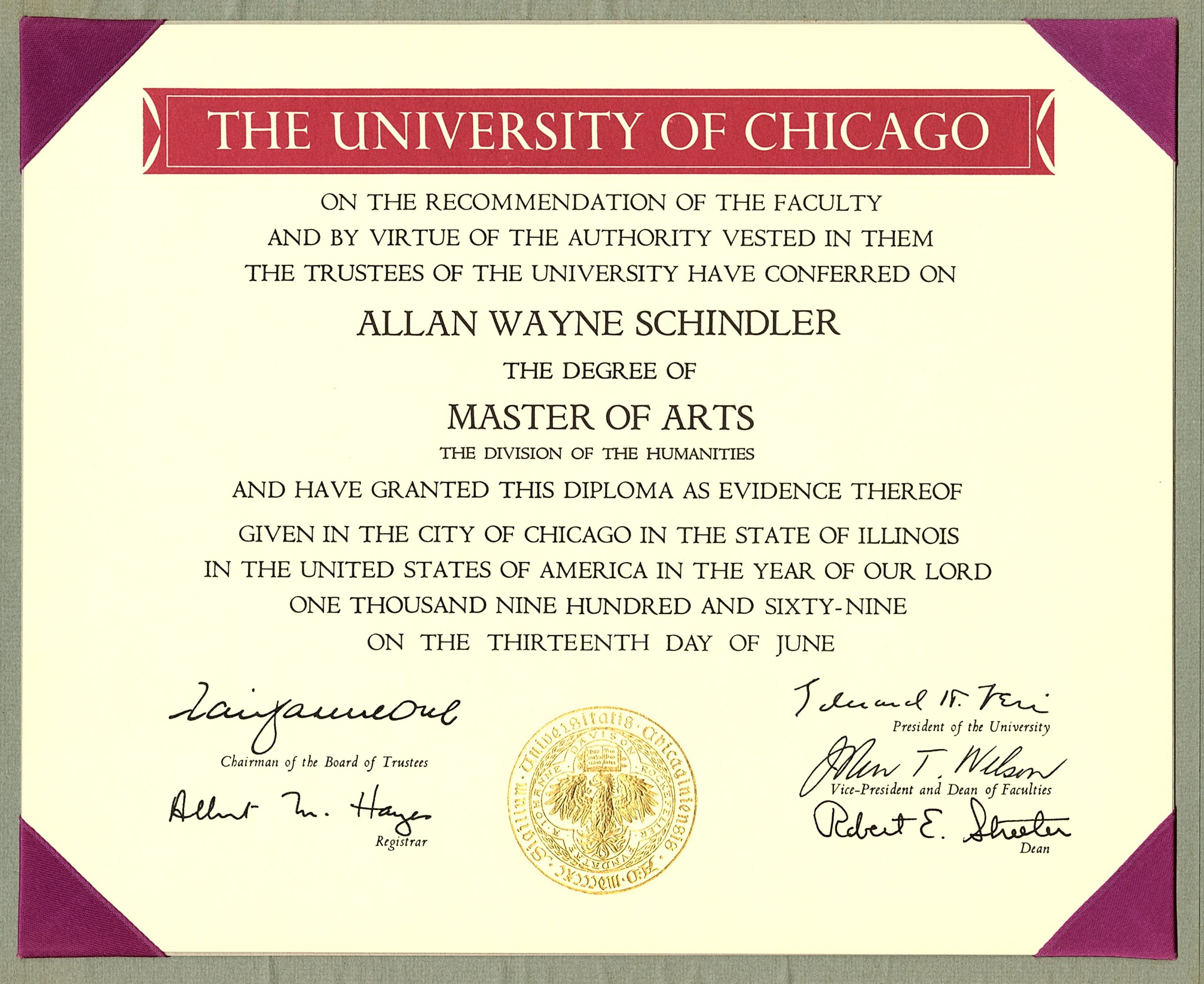

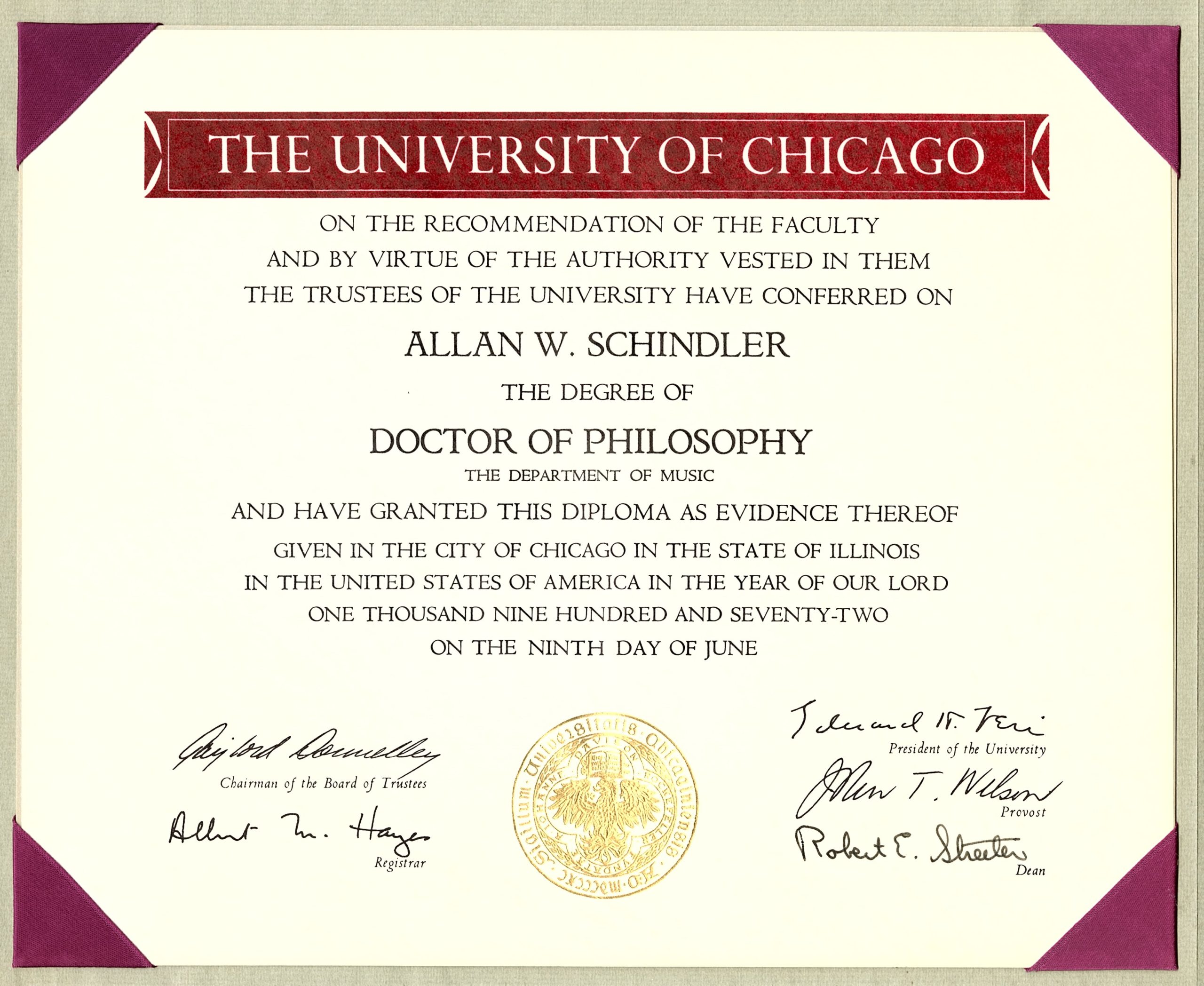

After earning dual bachelor’s degrees from Oberlin College—namely, a Bachelor of Music in Music Composition and a Bachelor of Arts in English Literature (1967)—Schindler pursued graduate studies at the University of Chicago, completing a Master of Arts (1969) and Doctorate of Philosophy in Music Composition (1971) with additional studies in musicology. For his master’s thesis, Schindler composed a technically demanding String Sextet (1969), which he dedicated to his teacher and mentor Ralph Shapey. (Schindler later described Shapey as “the finest, most uncompromising [if also the most difficult] teacher I have ever known.”[1])

The String Sextet was one of the few early works Schindler continued to promote as a mature composer.[2] In his program notes for a 2003 performance by the Eastman School of Music’s new music ensemble Ossia, the composer noted the work’s significance in his oeuvre as an early representation of his interest in rhythmic and textural layering and superimposition—features that can be heard across his more mature compositions, including his late, non-acoustic works. In the more detailed composer’s notes he wrote for the Sextet on his personal website, Schindler summarized several of the compositional techniques he employed in the piece:

The sextet is a technically demanding piece — a high-water mark in the exploration of simultaneous, asynchronous and “irrational” metrical structures that fascinated me during my early- and mid-twenties. Conceived primarily in terms of rhythmic and textural patterns, the work employed no compositional system other than my ear, and was written in a comparatively brief period of time, despite frequent interruptions. It also was composed during a tumultuous period in my life when I was living at the edge as an anti-war draft resister at the height of the Vietnam War.

Each of the six sections is based upon self-contained thematic ideas. However, the sections do not function independently, in the manner of classical movements (they would sound fragmentary or inconclusive if performed out of context), but rather contribute to a broader pattern of inexorable movement and pacing that runs throughout the piece. Formally, the piece reflects an attempt to structure a large unit of time through a simple (and fairly traditional) pattern of alternating accumulation and release of tension. Extreme rhythmic/metrical tension generated in the opening section is gradually dissipated in a cello cadence and a static interlude, then regenerated texturally in sections four and five, and finally resolved in the concluding section.[3]

2

After completing a master’s degree, Schindler accepted a position at Ball State University teaching composition and theory as well as conducting the university’s new music ensemble (1969–1970). In 1970, Schindler returned to the University of Chicago to complete the PhD in Composition, again studying with Ralph Shapey and Richard Wernick.

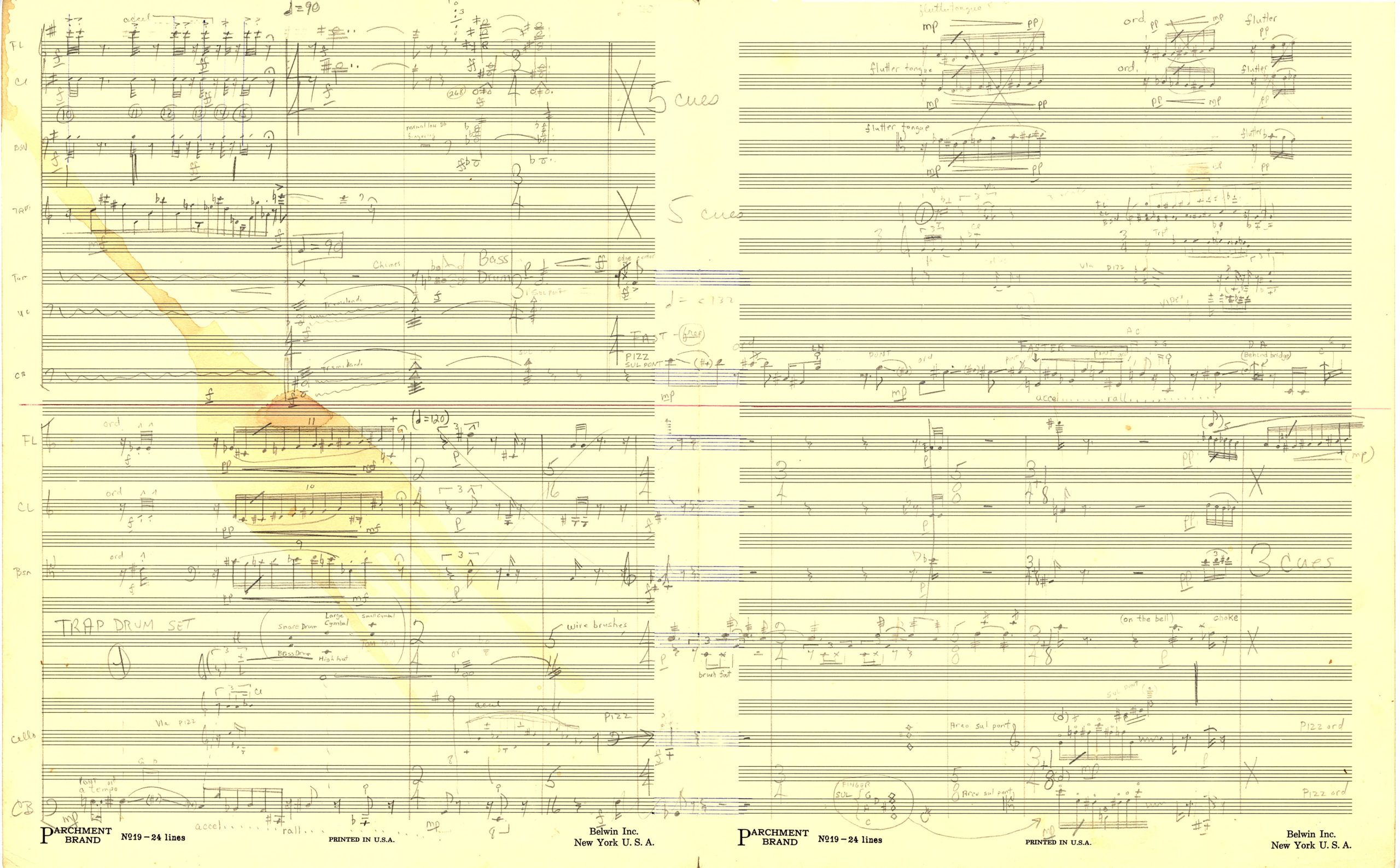

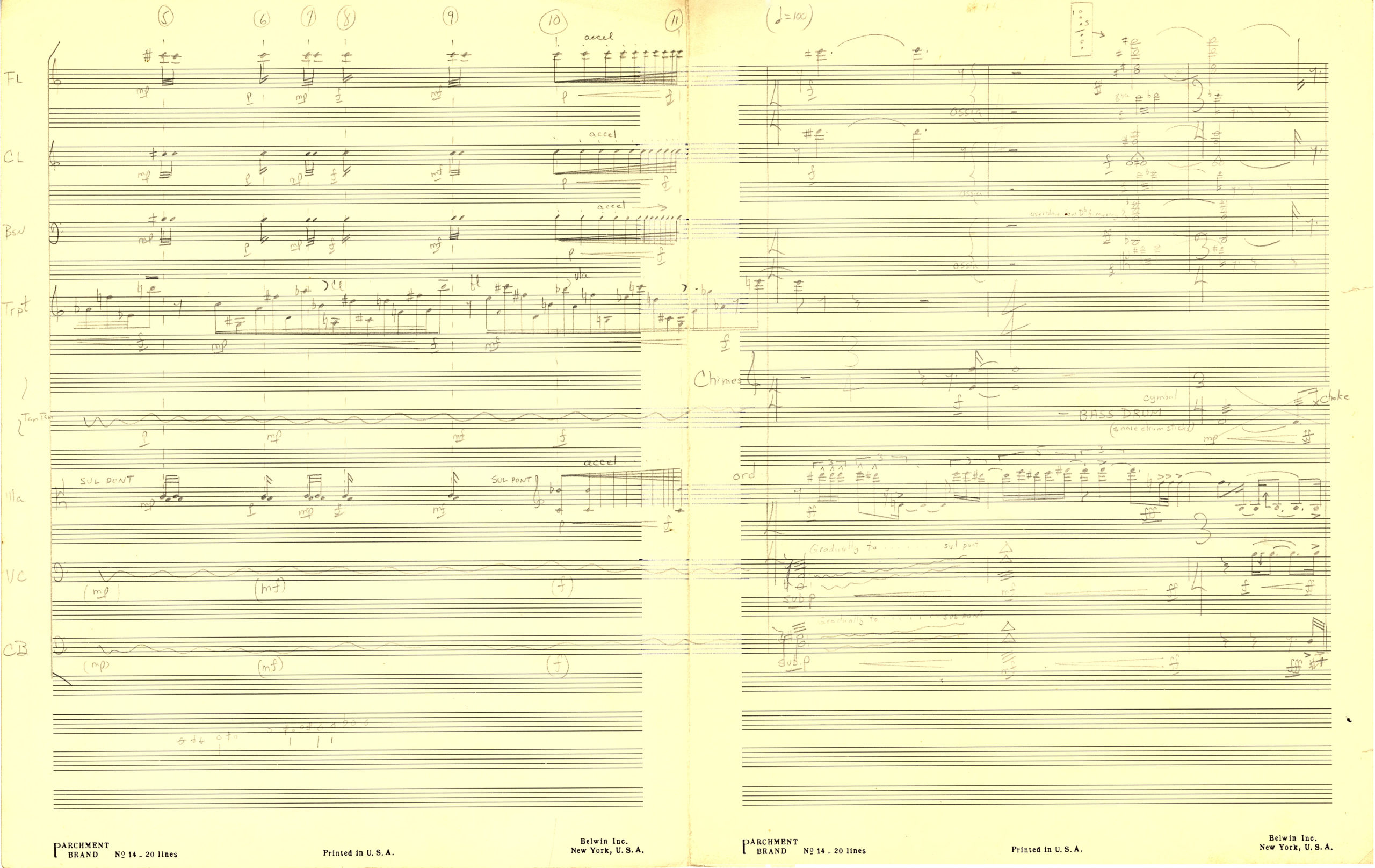

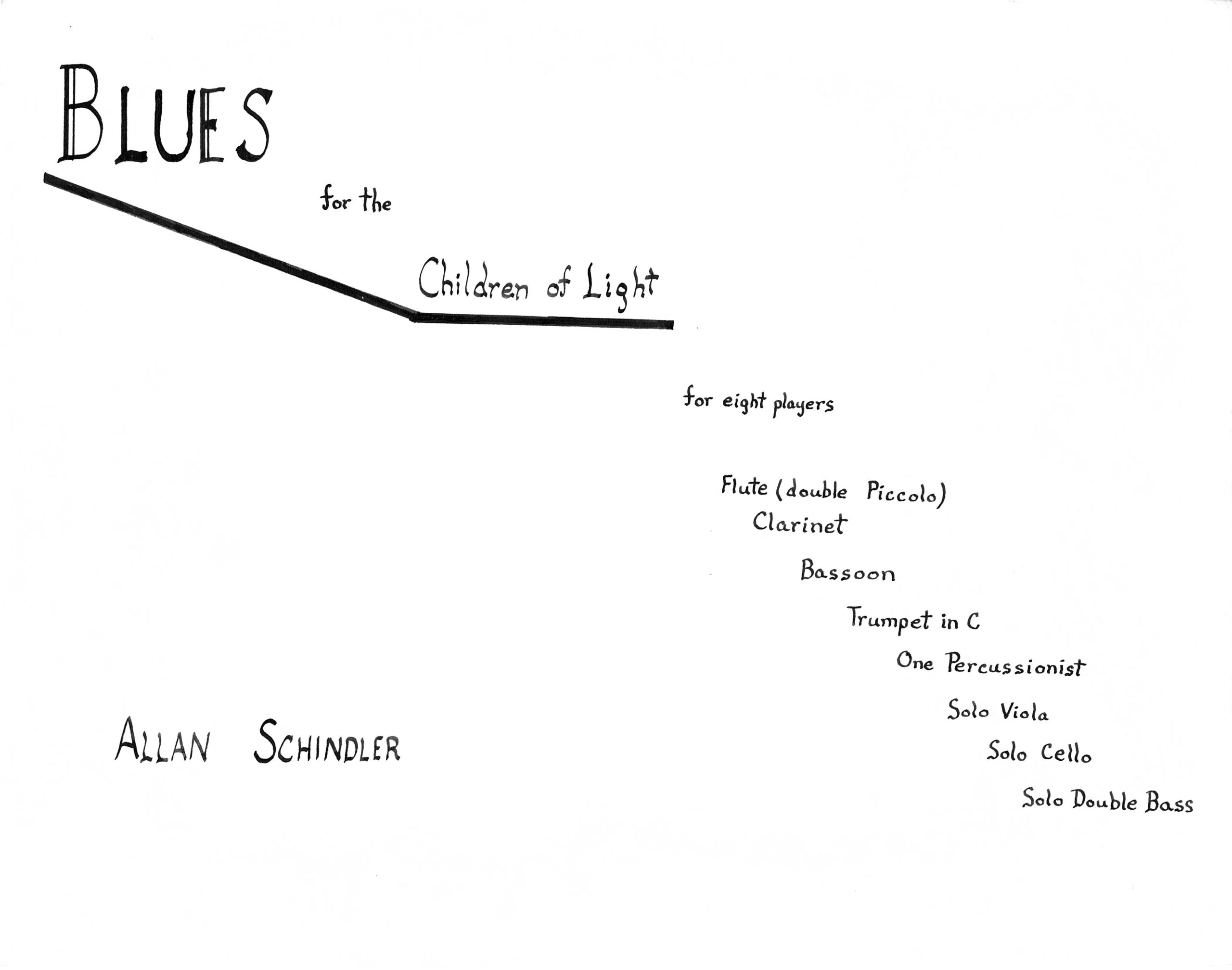

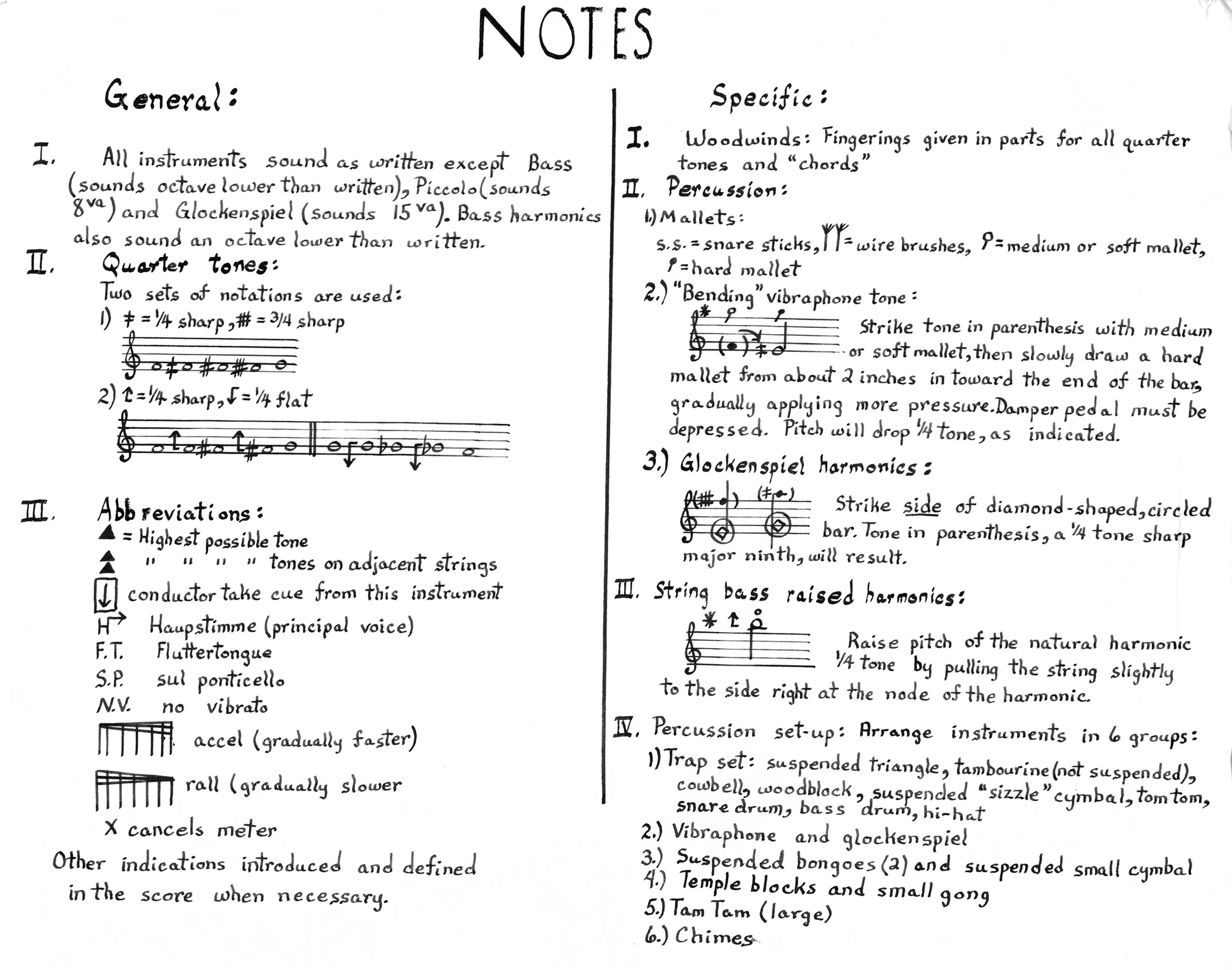

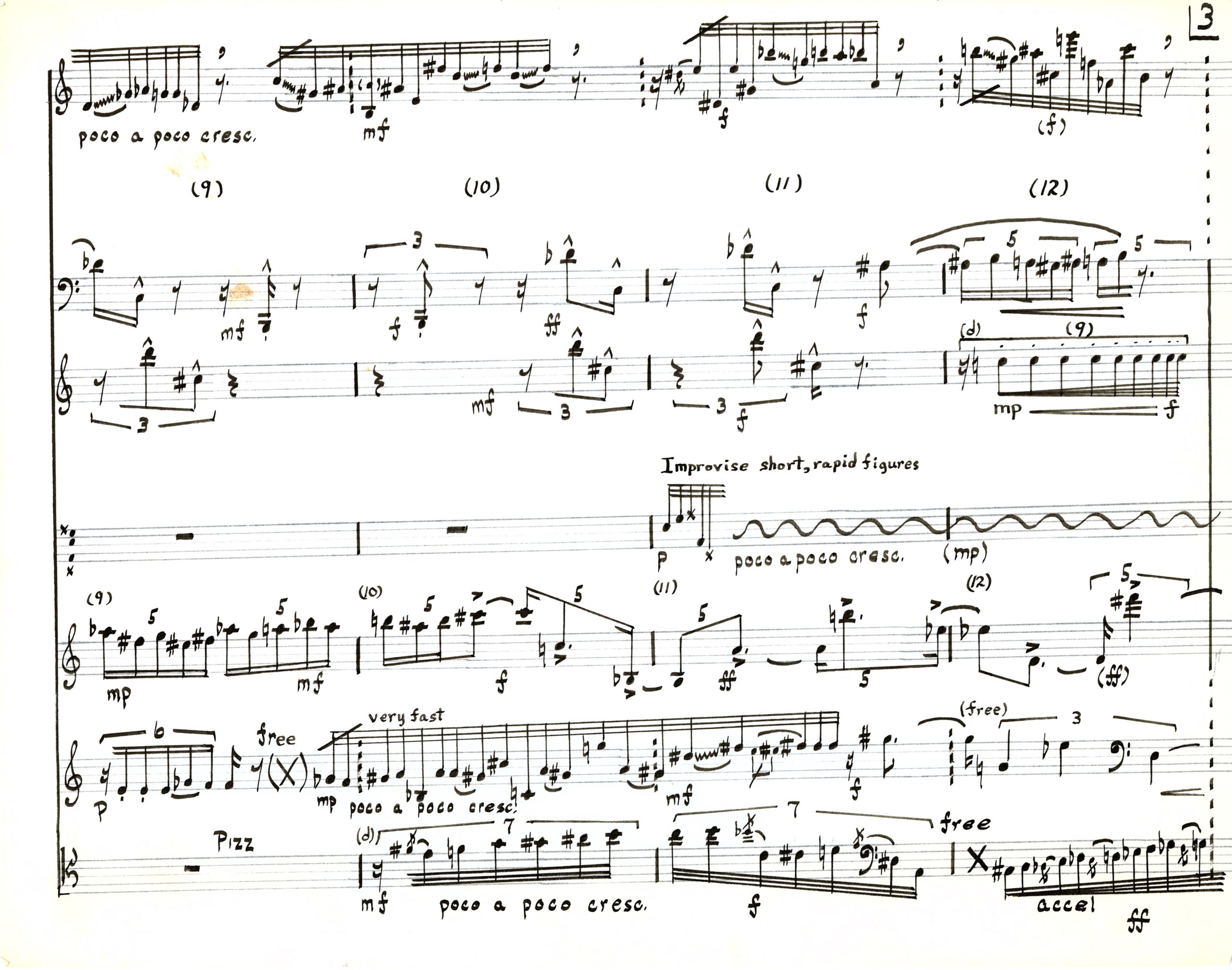

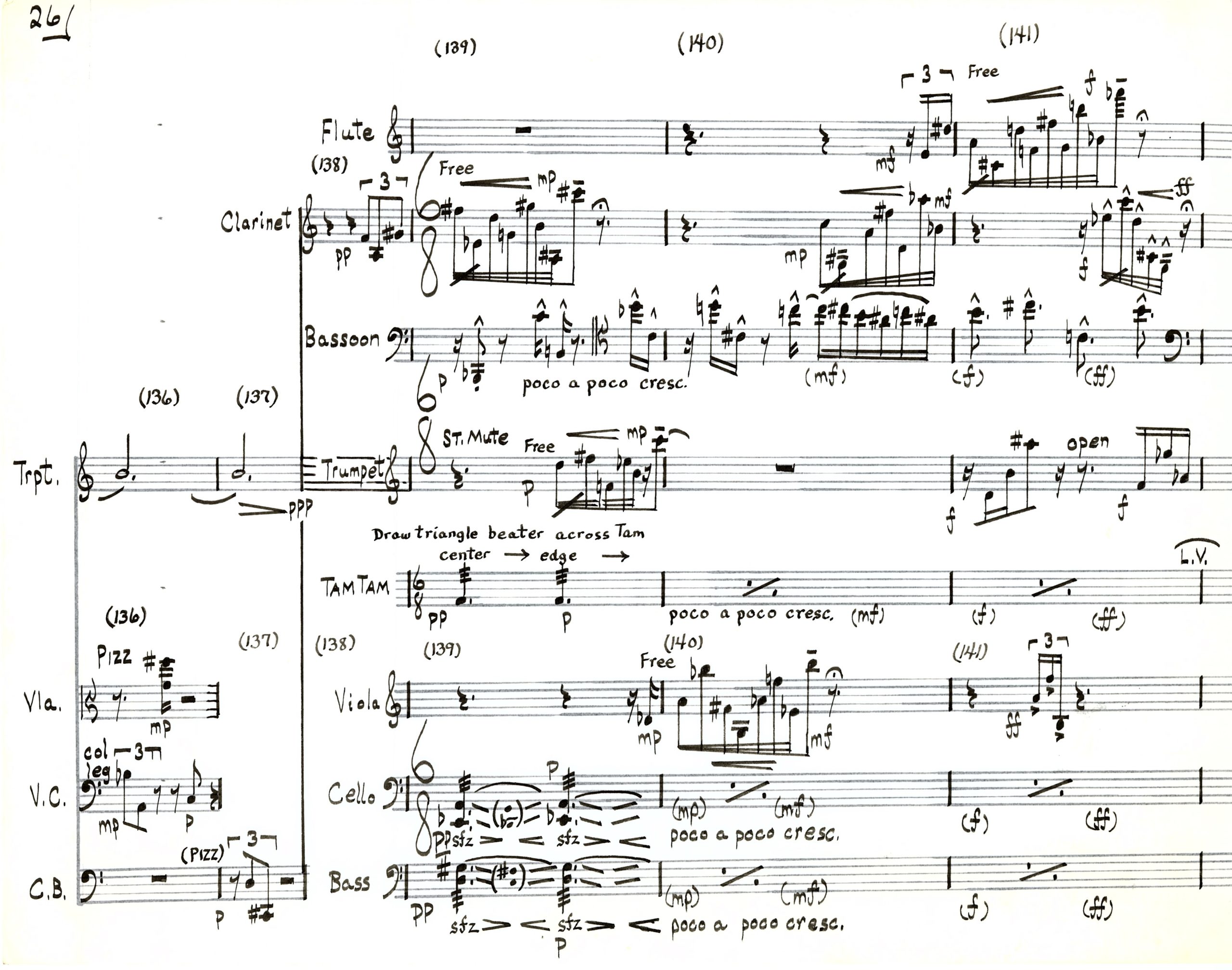

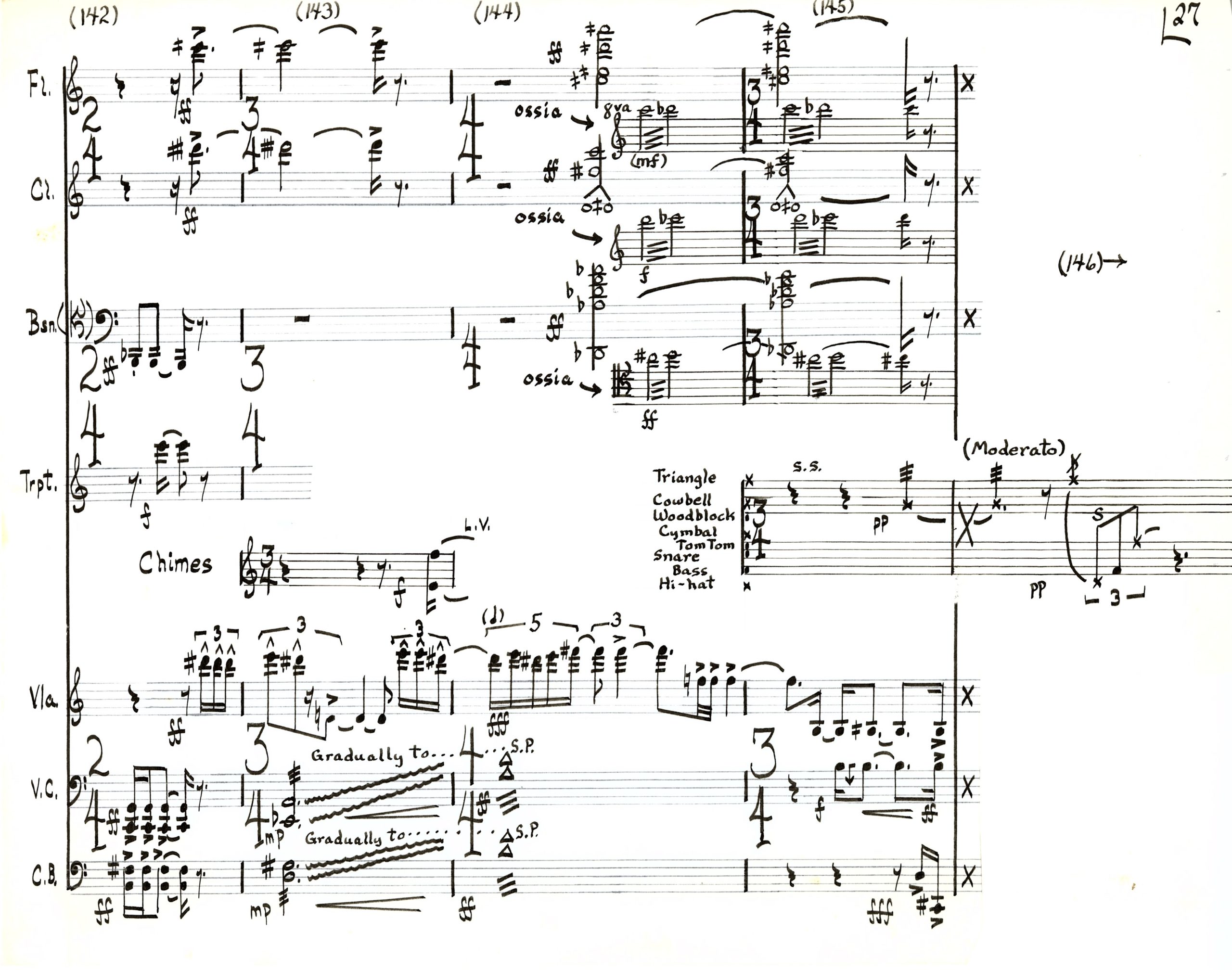

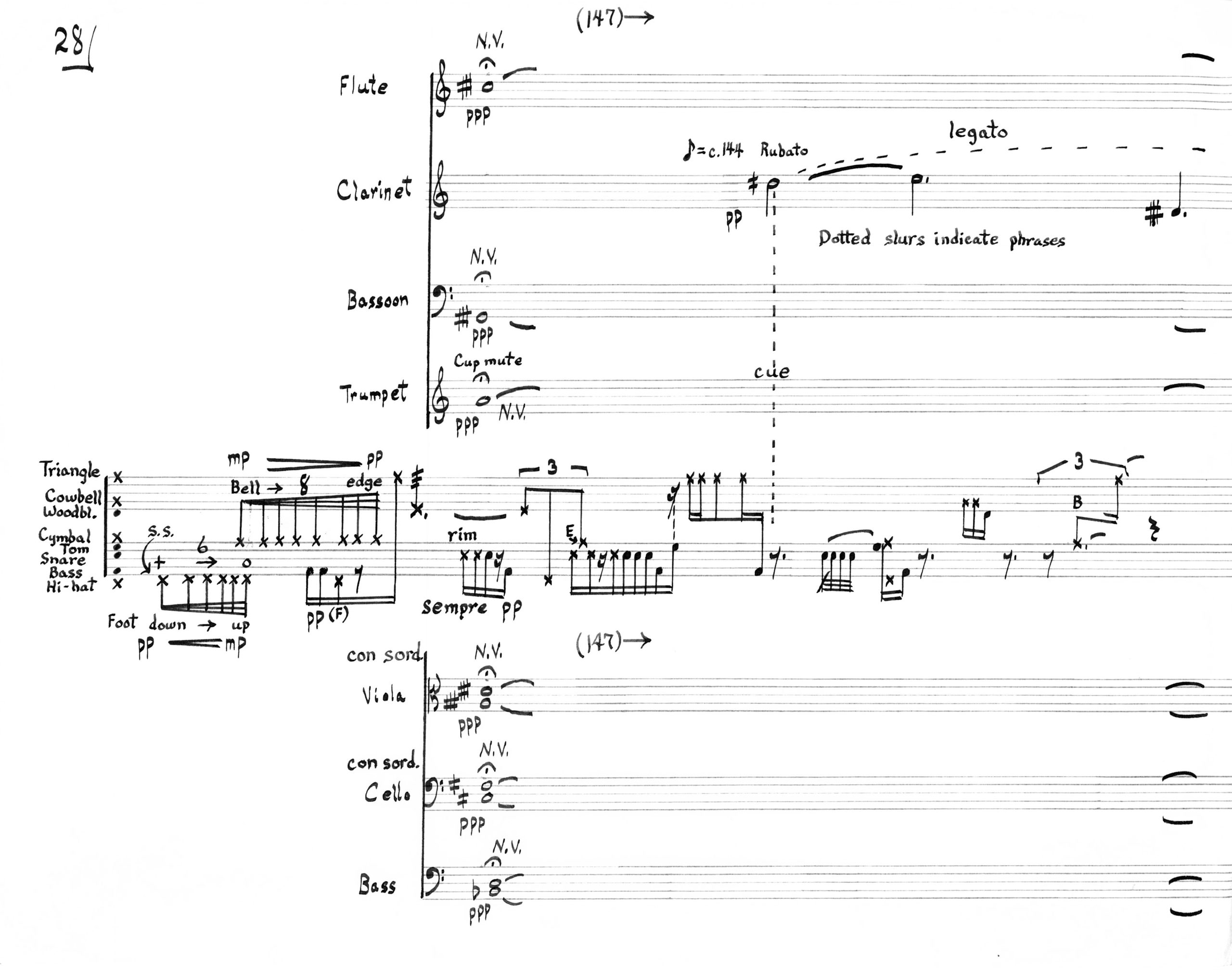

Schindler’s PhD dissertation was a chamber work for mixed ensemble titled Blues for the Children of Light (1972). Following then au courante compositional trends, the piece employs a range of extended techniques—most prominently quarter tones, glissandi and pitch bending, multiphonics, harmonics, and extramusical sounds (e.g., key clicks). It also includes figures notated in free rhythm and sections of improvisatory material.

Through his graduate studies at the University of Chicago, Schindler also built a strong foundation in analytical research and scholarship. The Allan Schindler Collection preserves his March 1972 paper “Clarity and Ambiguity in Beethoven’s Grosse Fugue: A Study of Melodic and Rhythmic Design,” which Schindler submitted to the Department of Music as part of in candidacy for his PhD. The paper is a model of his clear writing, eloquent phrasing, and astute analysis, qualities Schindler would apply throughout his career in composer’s and program notes for his compositions, scholarly articles and reviews, textbooks and reference materials, and other publications as well as in his work as a consulting editor for several publishers.

3

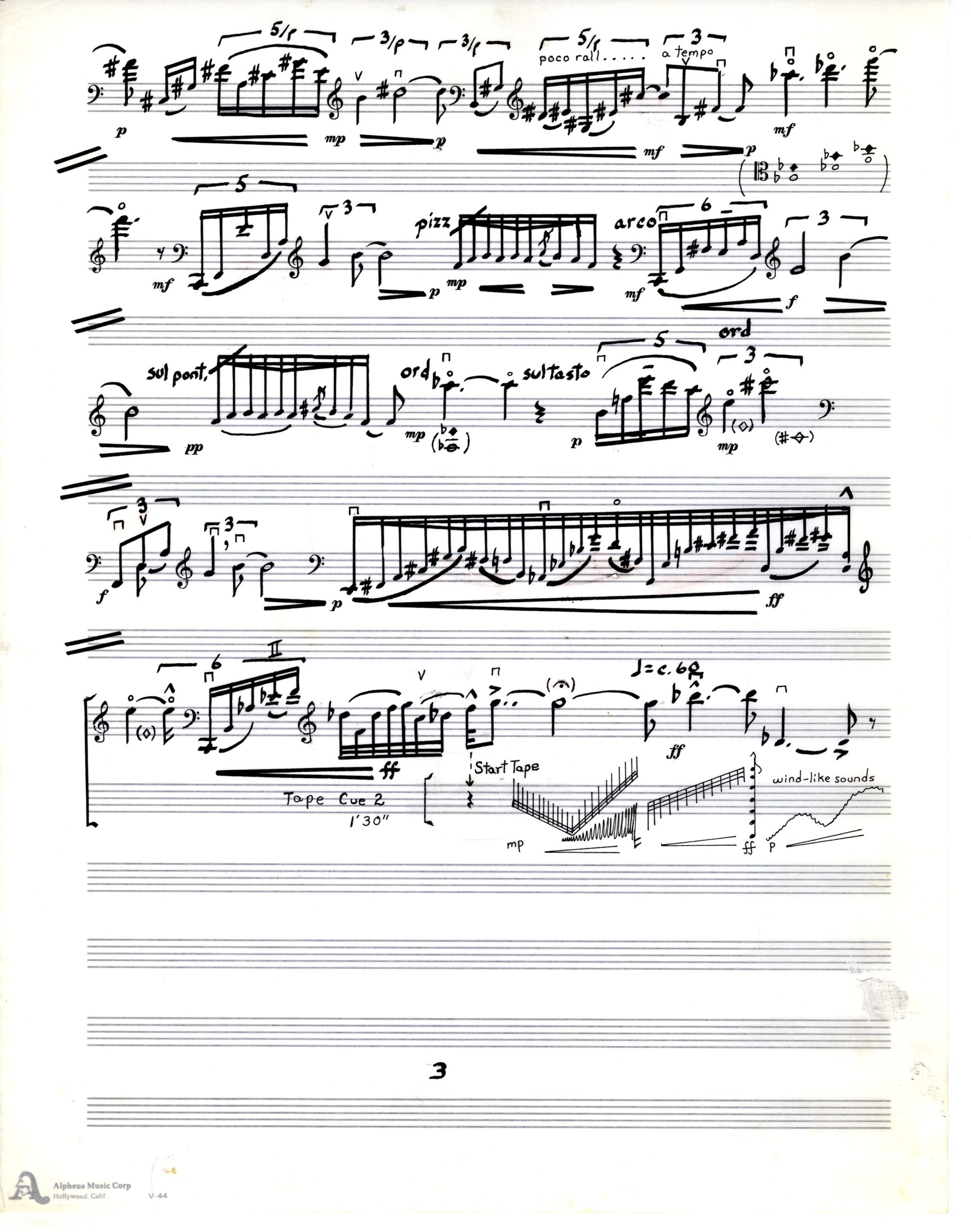

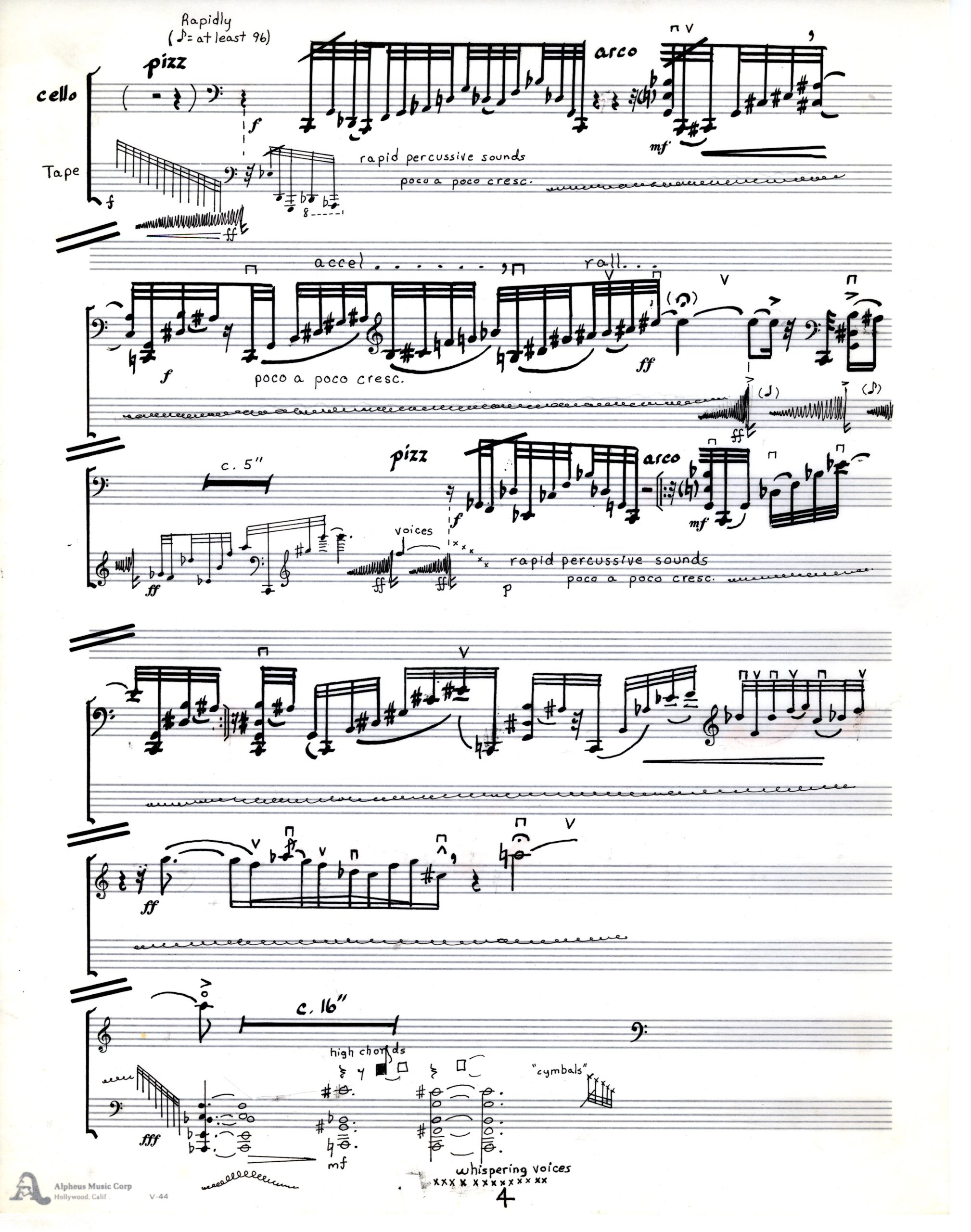

In 1972, Schindler joined the faculty of Boston University as Assistant Professor of Composition and Director of Electronic Music. During his seven years at the university (1972–1978), Schindler taught graduate seminars in contemporary and tonal theory, directed the school’s electroacoustic music program, and participated in the production of new music concerts throughout the Boston area. Scores and recordings of two of his early explorations into electronic music, both completed during his time in Boston, are preserved among his papers. The first of these, Cirrus, and Beyond (1975), is a chamber piece for flute, violoncello, percussion, and synthesizer sounds on tape, which the composer dedicated to his son Garrick, and the second, Visionary (1977), for flute, clarinet, bassoon, violin, harp, and tape, was dedicated to his daughter Danielle.

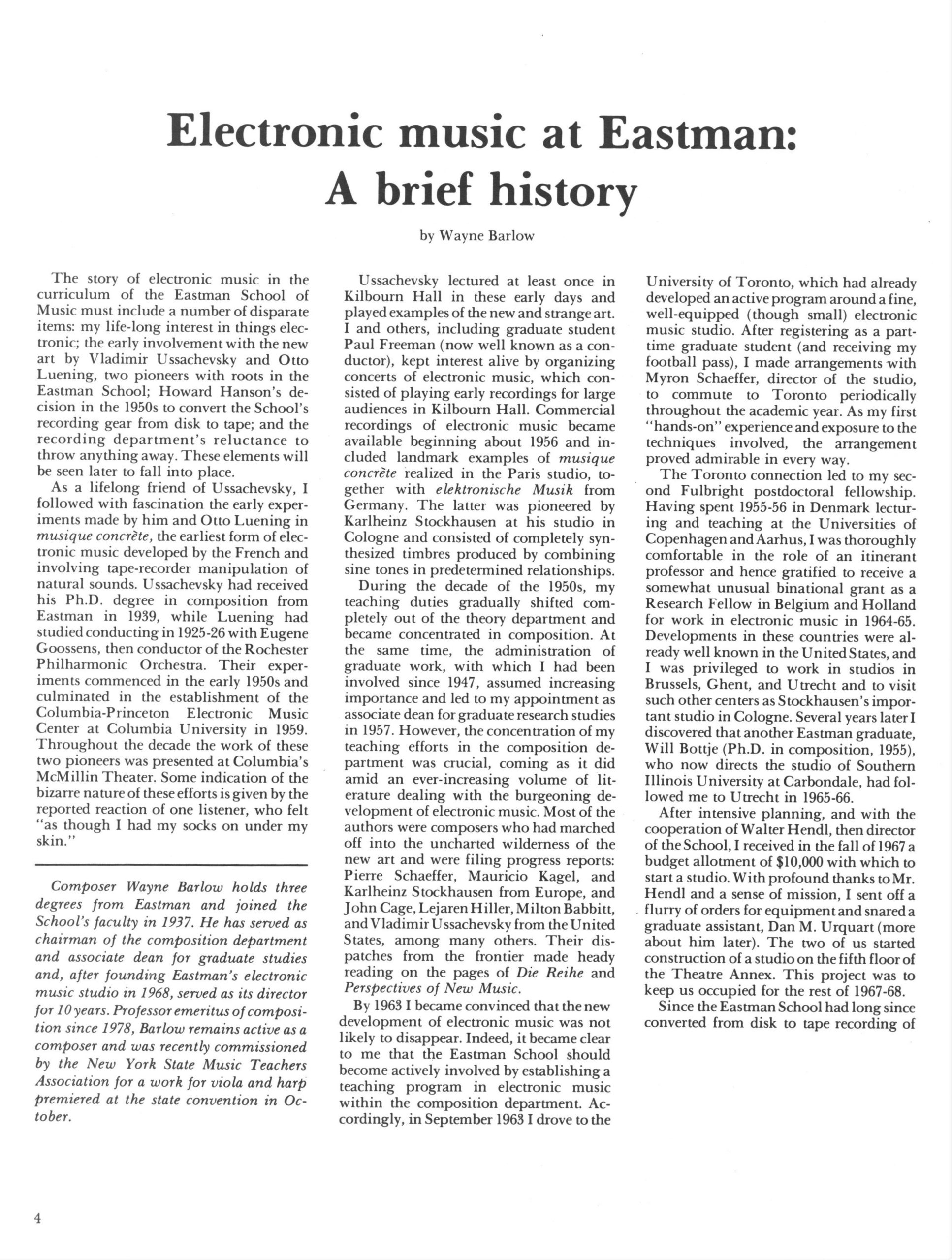

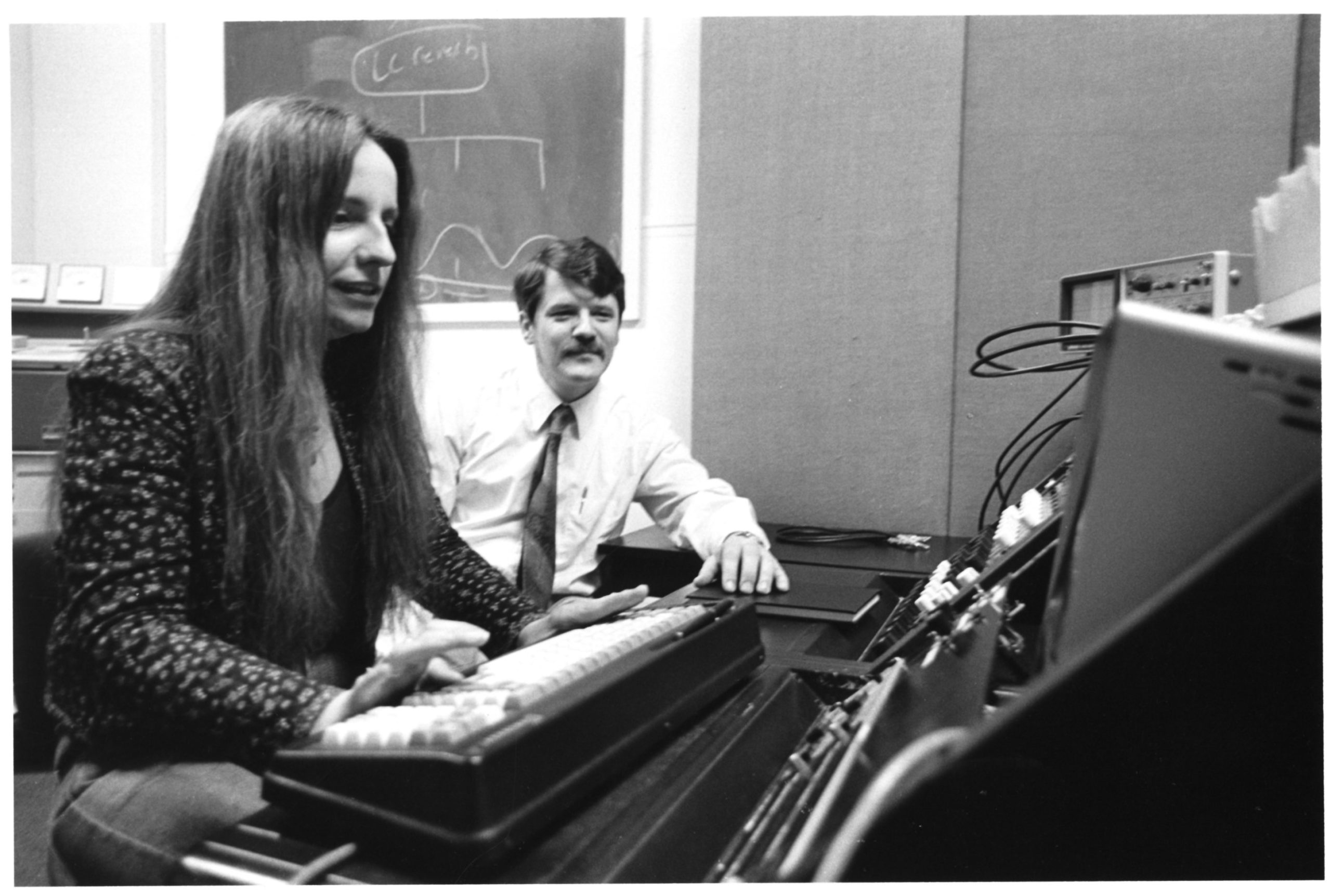

In 1978, Schindler accepted a position at the Eastman School of Music as a Professor of Composition with the special directive to update and expand the school’s Electronic Music Studio. The studio had been founded in 1967 by Wayne Barlow, an Eastman alum (BM 1934, MM 1935, PhD 1937) and longtime Professor of Composition (1937–1978), after intensive research into successful electronic music programs at prominent universities in Europe and Canada. (Barlow’s article “Electronic music at Eastman: A brief history” from Eastman Notes, shown above, provides a detailed history of the studio’s founding and development.) By the time Prof. Barlow retired in 1978, given the emergence of digital audio, Eastman’s Electronic Music Studio was already falling out of date. An increasing number of composers and musicians had begun utilizing computer programming techniques to manipulate digital sound and exert increased creative control over their music. Schindler led the initiative to redesign the studio with a PDP-11/34 “mini-computer” (which, as Schindler notes, was “the size and weight of a good sized refrigerator”) and other necessary hardware for working with digital audio. By December 1980, the new studio—later renamed the Eastman Computer Music Studio (ECMS)—had been installed in a basement suite in Eastman’s newly renovated East Wing. A cover story on the installation of the new studio in Eastman Notes featured photographs of Schindler and Robert Gross, a graduate student in Eastman’s Composition Department and member of the ECMC staff, working in the new studio.

The transition was not without its issues, as Schindler later recounted in his 2006 essay “A (not so brief) History of the Eastman Computer Music Center” reflecting on ECMC’s 25th anniversary. The PDP-11 mini-computer was often unstable, sometimes crashing several times a day. It took nearly a year for the computer system to become sufficiently functional that it could support classroom instruction and two years before Eastman students and faculty began producing substantial compositions using the equipment.

4

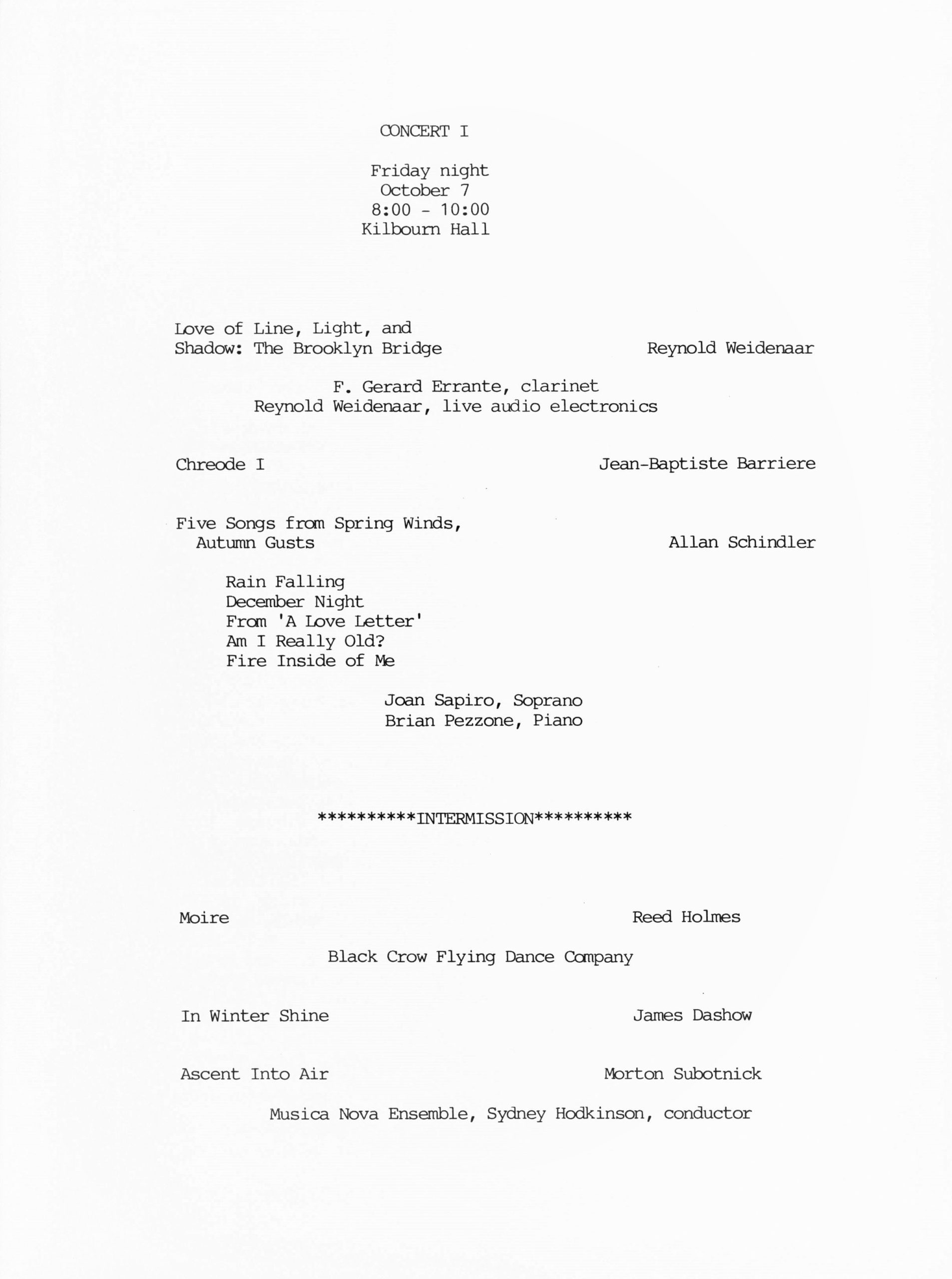

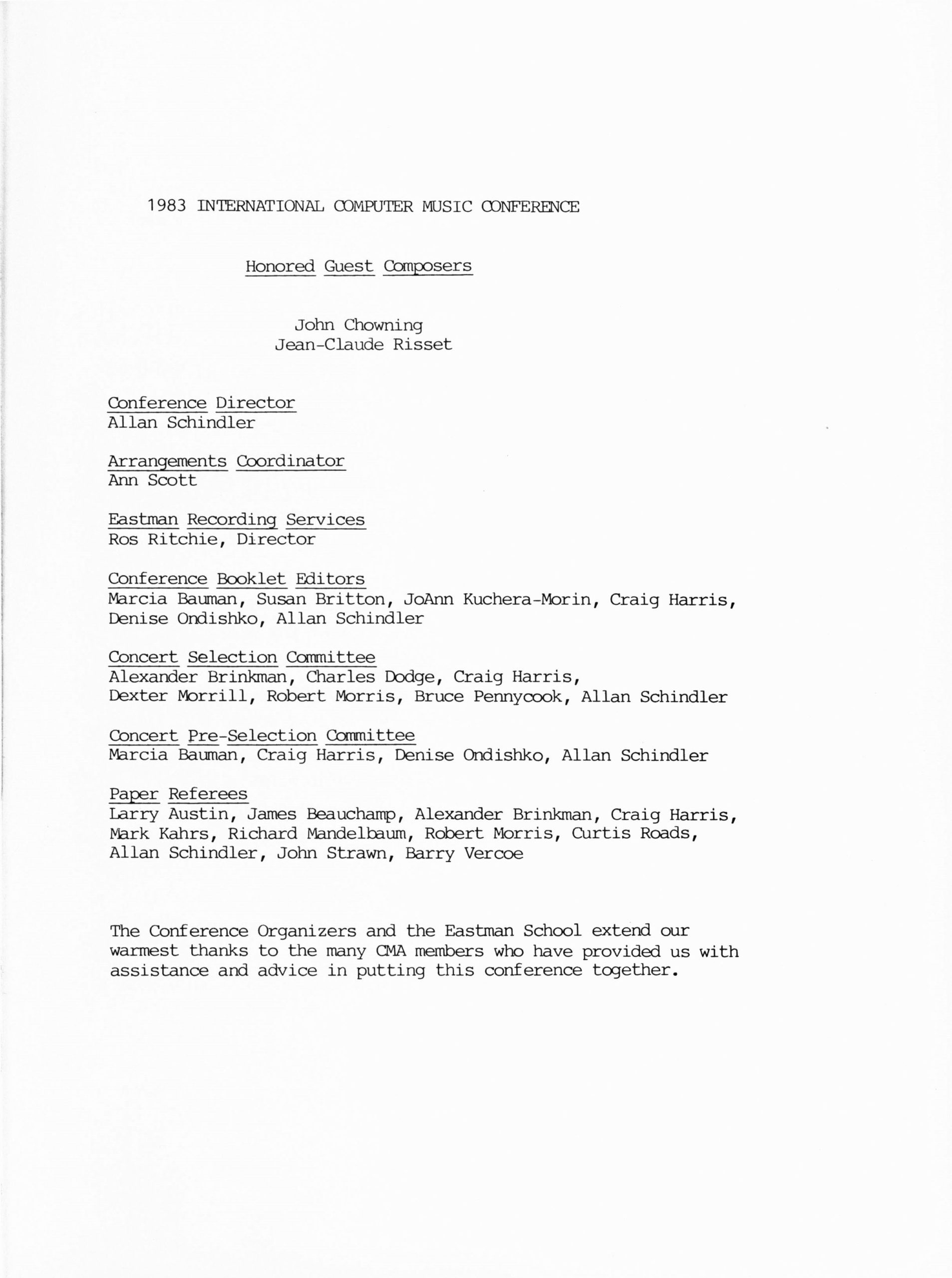

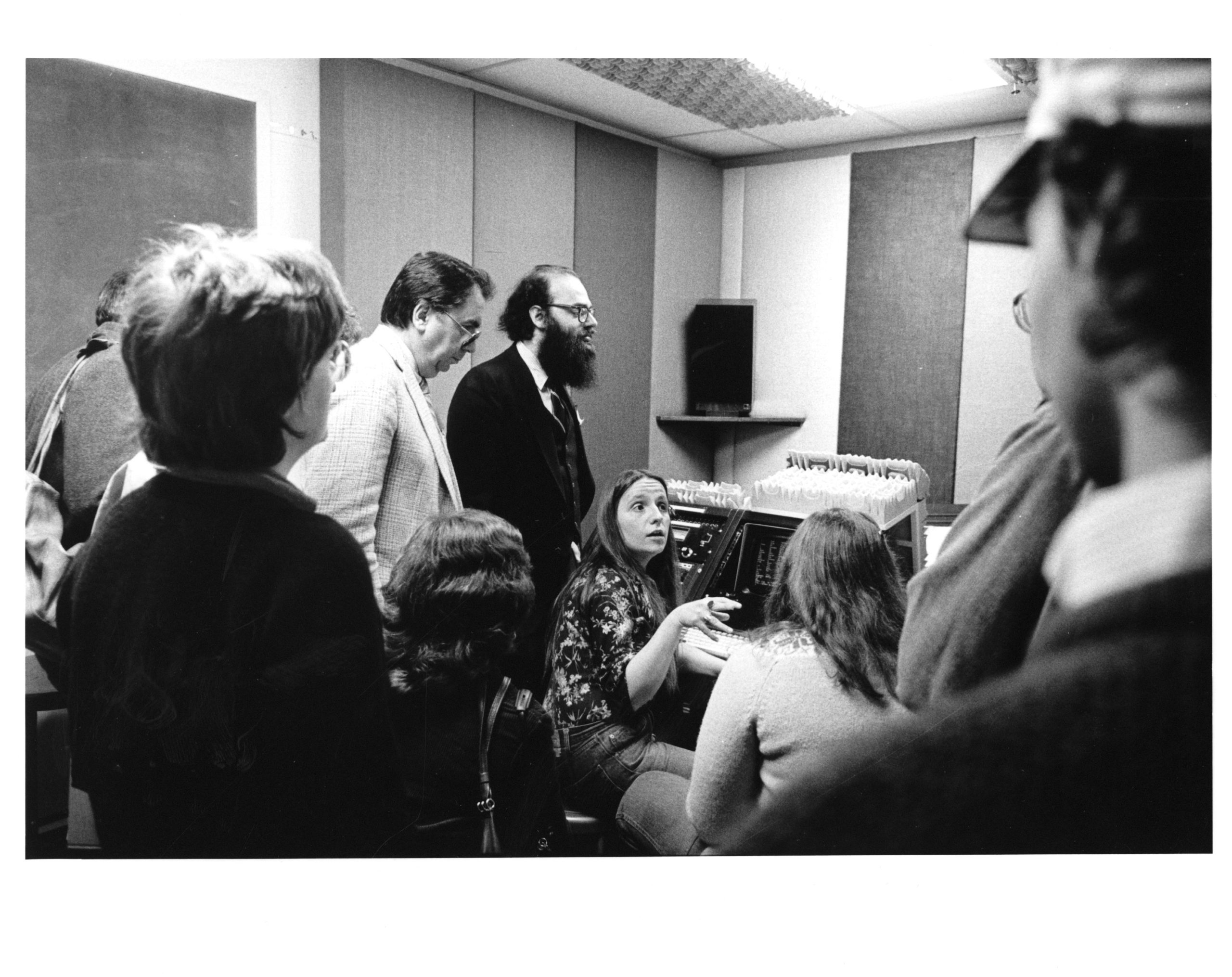

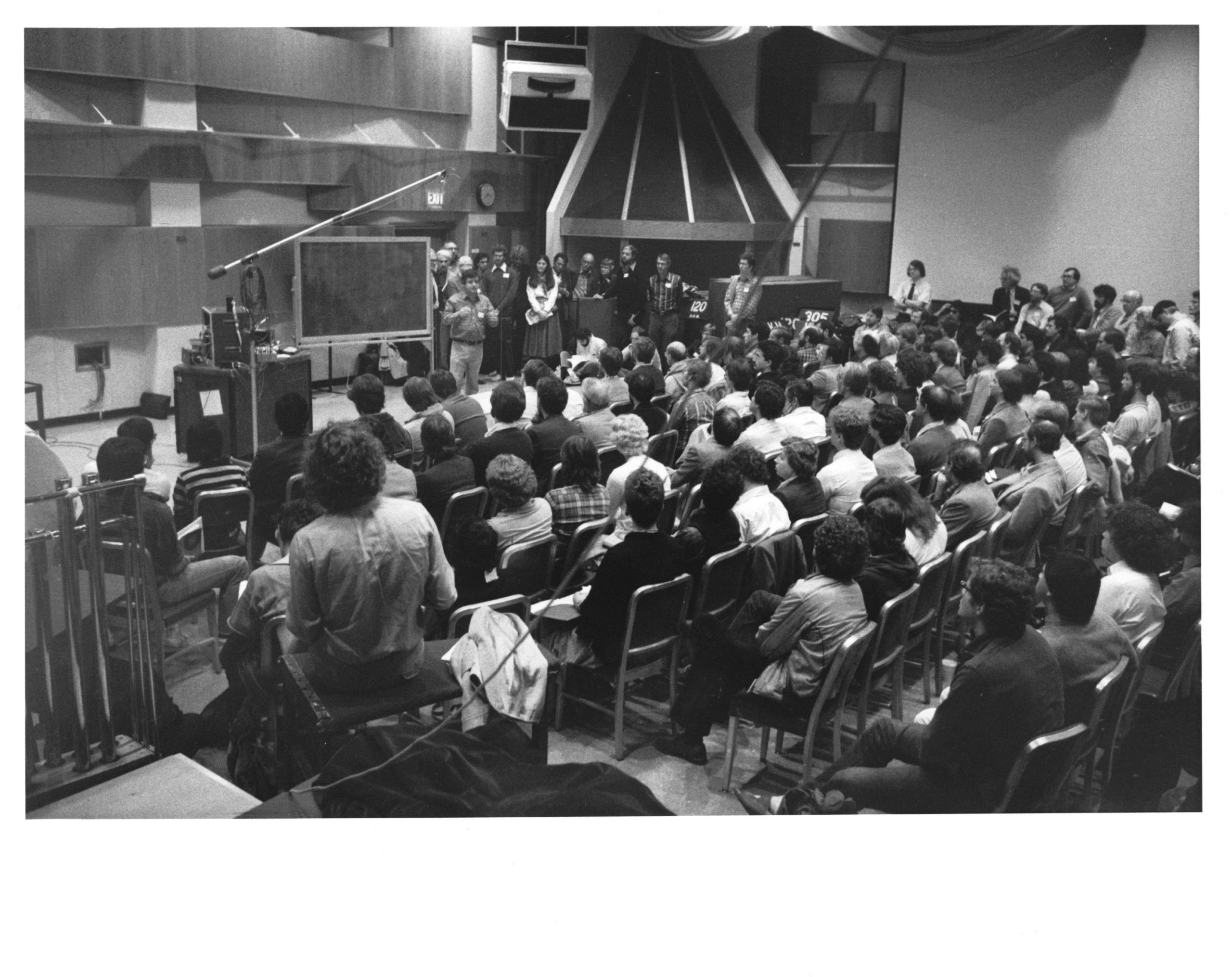

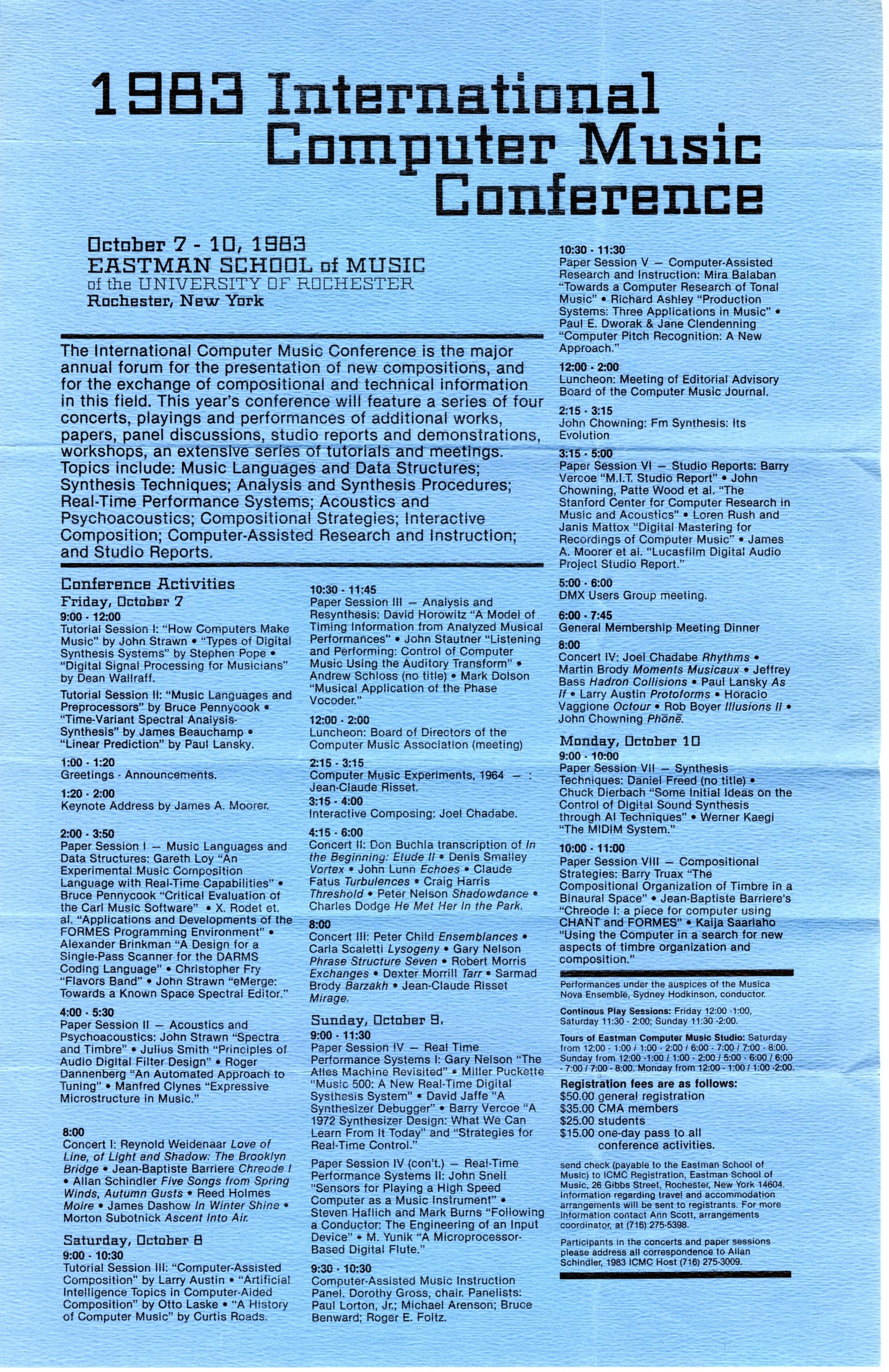

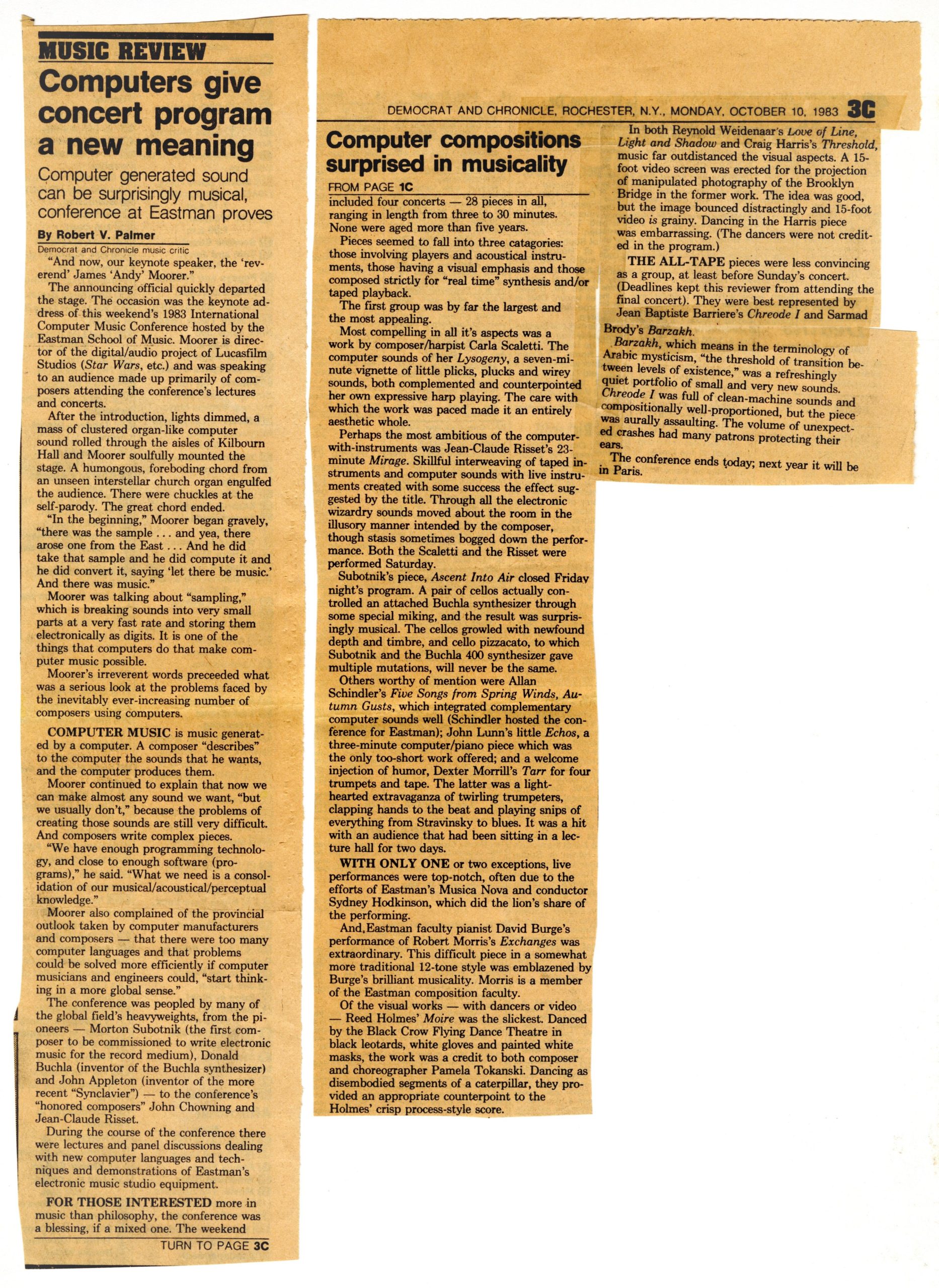

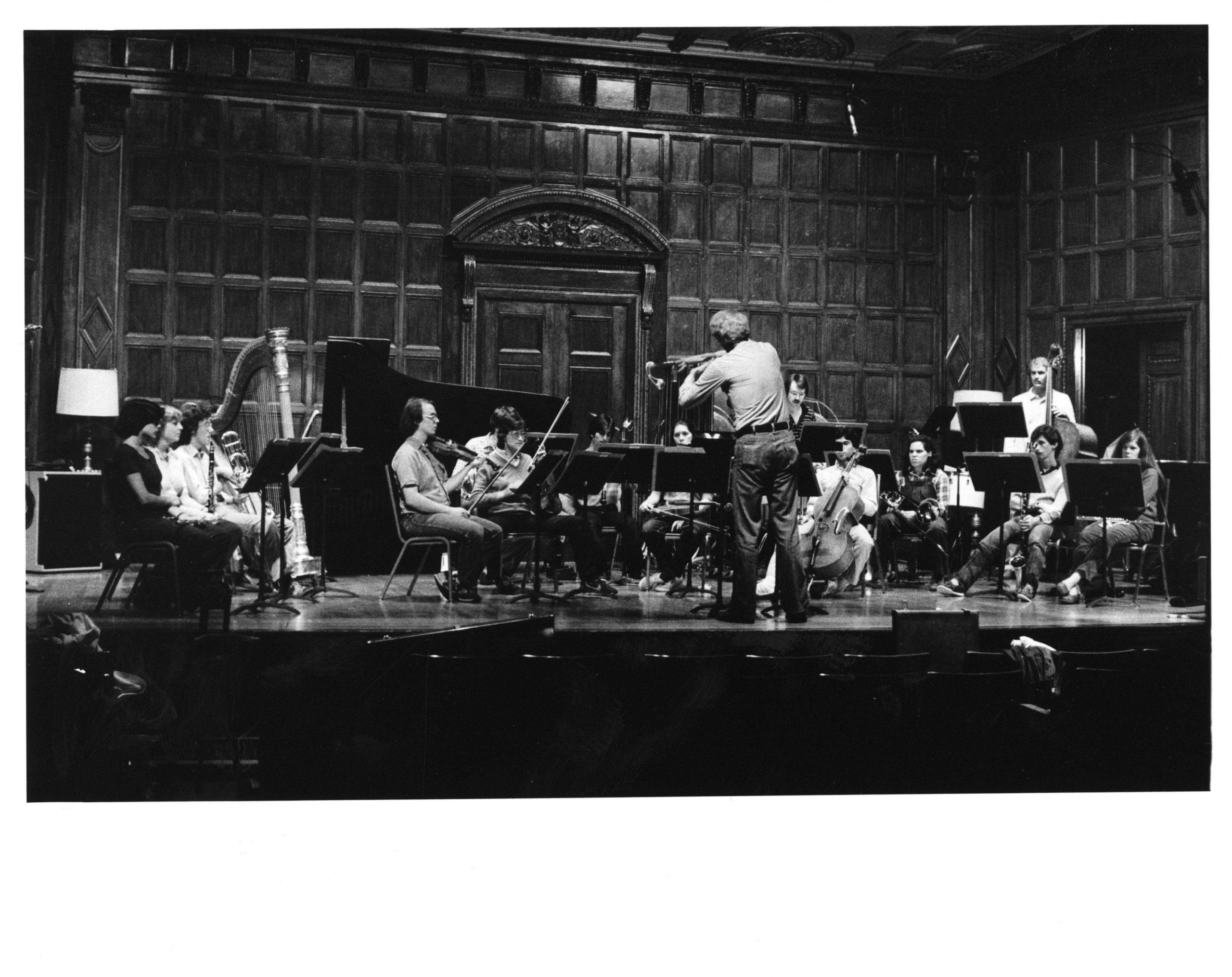

By 1983, the Eastman Computer Music Center had become internationally known as an important center for electroacoustic music, and that fall, ECMC and the Eastman School of Music hosted the 1983 annual conference of the International Computer Music Association (ICMC), with Schindler serving as the Conference Director. Over the weekend of October 7–10, 1983, more than 400 musicians, composers, researchers, and developers attended paper sessions, lectures, panel discussions, tutorial sessions, and concerts. The conference also featured music and invited lectures by the acclaimed composers Jean-Claude Risset and John Chowning, both pioneers in electroacoustic and computer music and special guests for the 1983 conference, as well as a keynote address by digital audio and computer music engineer James A. Moorer, then the newly appointed head of Lucasfilm Studio’s digital audio group.

5

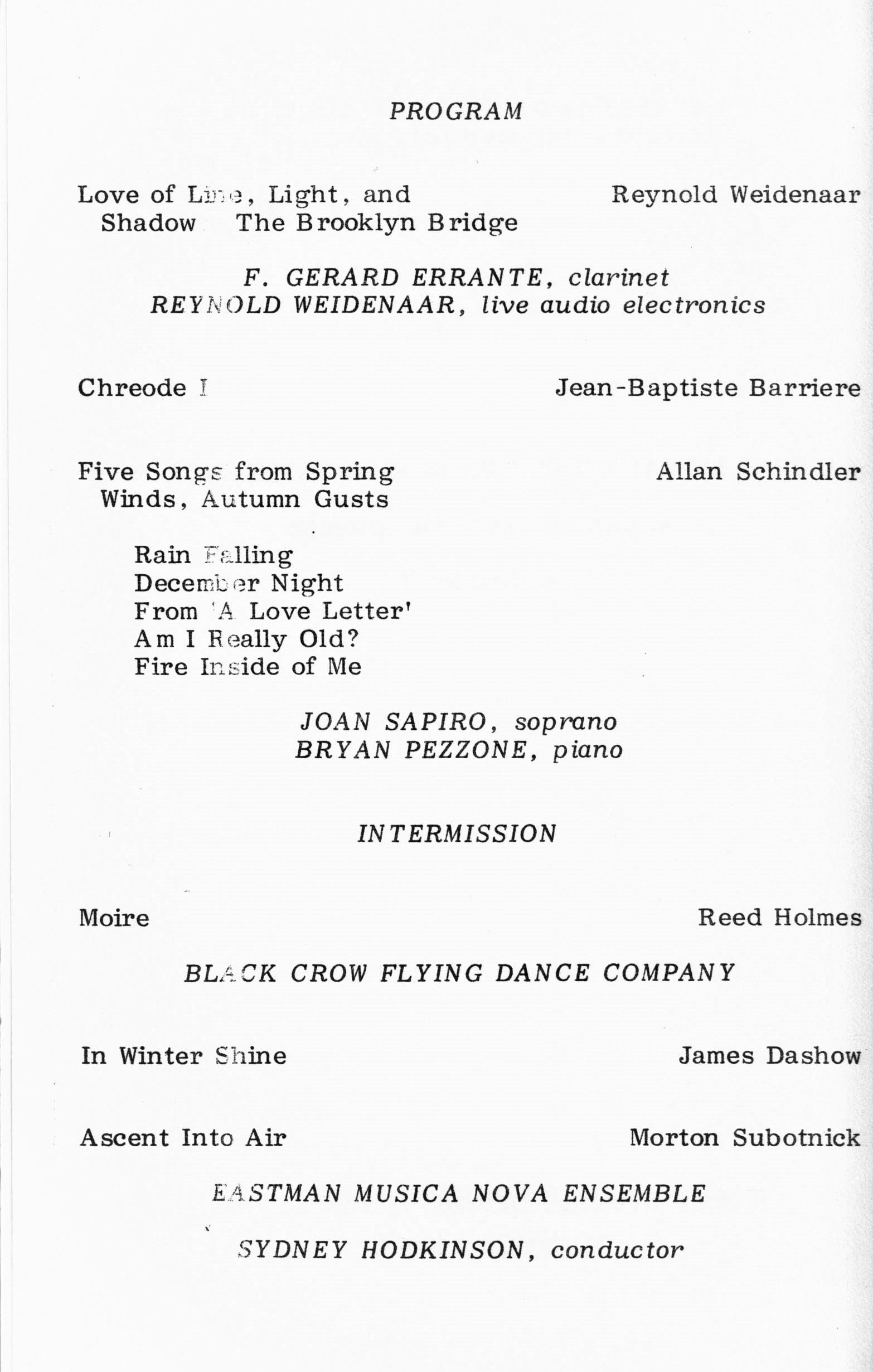

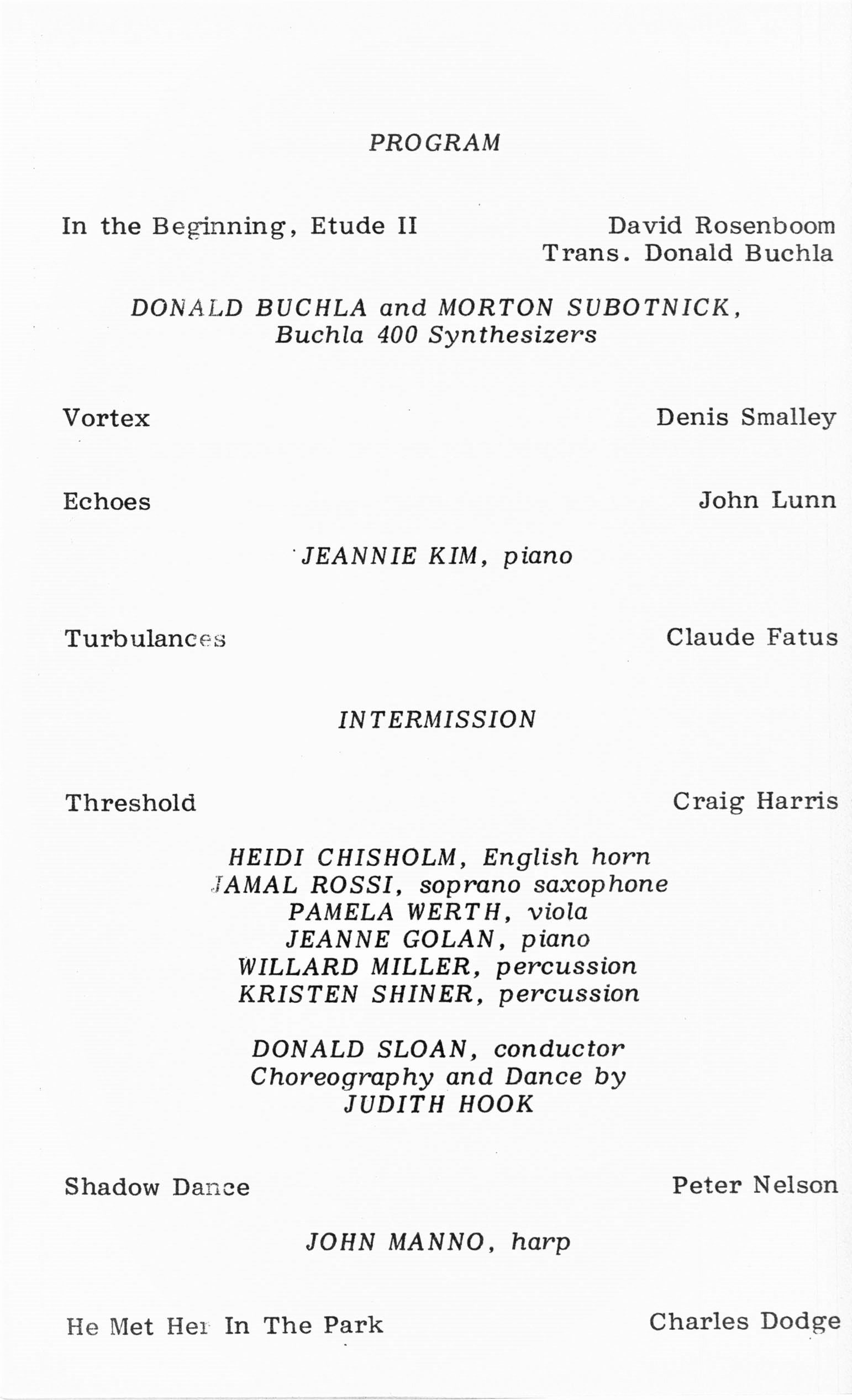

For the four concerts held during the 1983 ICMC, Schindler, with the other members of the conference selection committee, programmed 28 diverse works representing the most exciting developments in electronic and computer music composition. As quoted in an article on the conference for the New York Times, Schindler noted that among the music selected for the conference, the committee emphasized in particular works that incorporate live performers alongside taped computer sounds: “We worked very hard to make the concerts as varied and appealing as possible. We’re not just interested in far-out noises; we want the computer to make music.” Robert V. Palmer, music critic for Rochester’s Democrat and Chronicle, lauded the choice, remarking that several such works were particularly compelling—among them Carla Scaletti’s Lysogeny, Jean-Claude Risset’s Mirage, and Morton Subotnik’s Ascent Into Air. The concerts also included pieces for tape alone and works with live choreography or other visual elements, such as Moire by Reed Holmes, with choreography by Pamela Tokanski that was performed by the Black Crow Flying Dance Theatre.

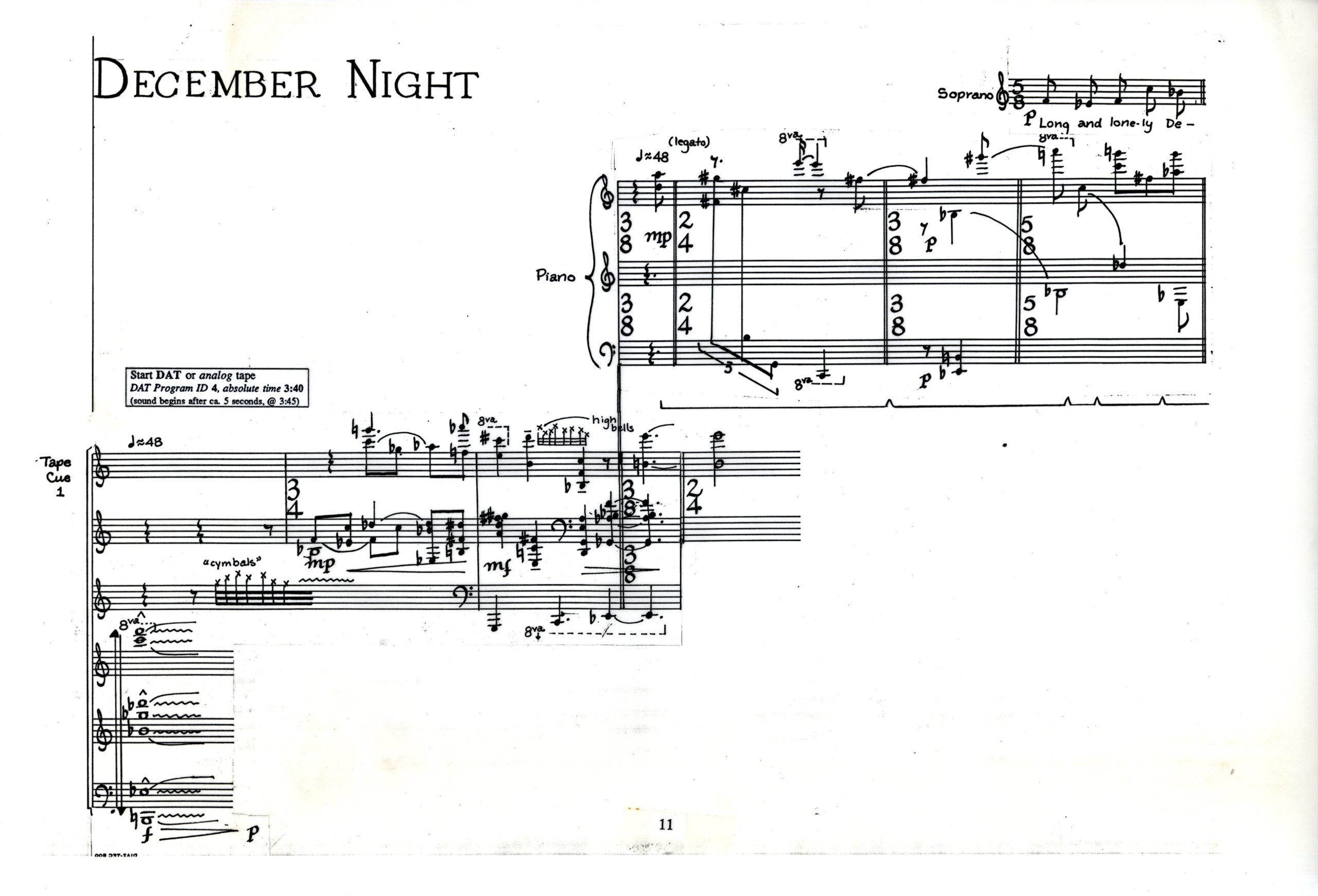

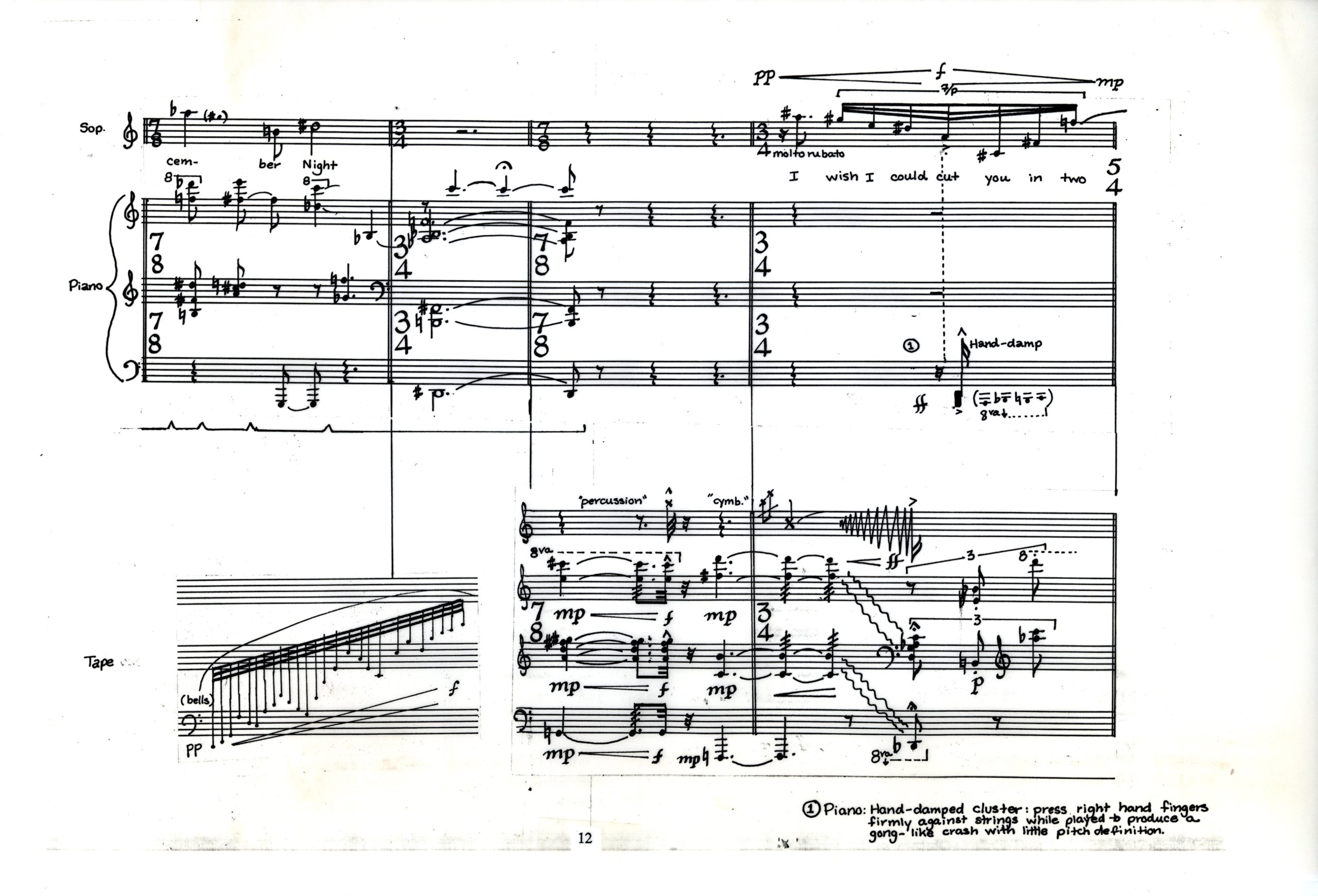

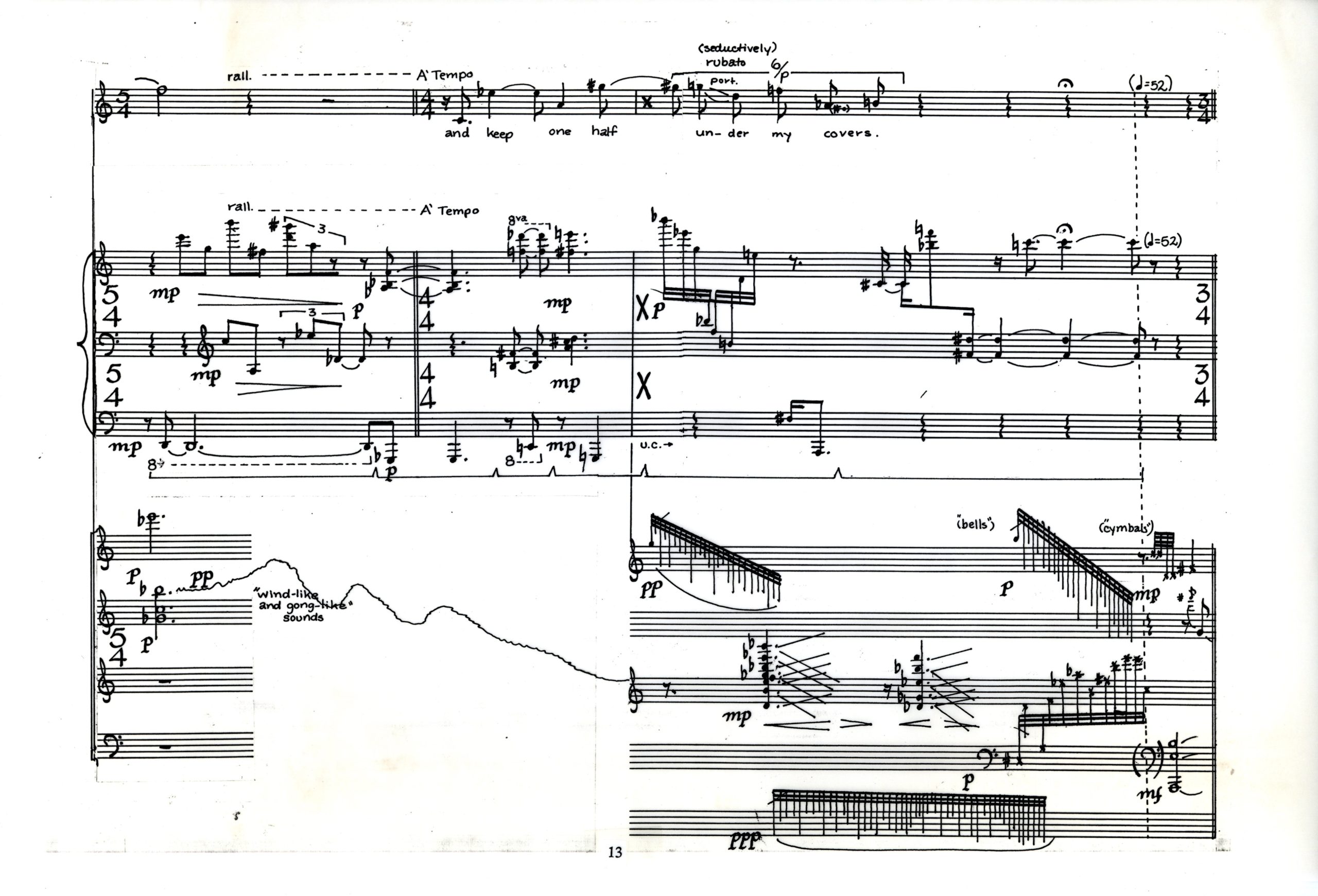

Palmer also praised Schindler’s own contribution—a set of five songs for lyric soprano, piano, and computer-generated sounds titled Spring Winds, Autumn Gusts (1983). In his program notes for the piece, Schindler explained his vision for the song cycle and described its primary musical features:

This song cycle deals with a woman’s growing self-awareness and inner strength, and with her realization that she has come to like the person that she is. The texts for four of the songs, translated and adapted by Virginia Olsen Baron, are taken from fifteenth and sixteenth century Korean sijo poems, a genre similar in some respects to Japanese haiku poetry. These “simple” (though at times ironic, cryptic or multi-layered) and eloquent poems are pervaded by nature imagery, which in this cycle also serves to mirror the woman’s personal thoughts and feelings. Anna Wickham’s A Love Letter reflects a similar quality of being “beyond time,” in the sense that one can feel simultaneously young and old, alone but fulfilled.

The soprano melodies are technically demanding, incorporating wide melodic leaps and an extended pitch compass, but at the same time often requiring an “effortless” lyricism. The piano part and the computer generated and processed sounds comprise a double, or mirror-like, accompaniment. Prominent melodic, harmonic and rhythmic ideas from the vocal and piano parts are frequently developed in more abstract fashion within the computer textures.[4]

6

Over the next decade, Schindler refined the technology and processes used in the ECMC studio and his courses on electronic music as well as those he applied in his own composition projects. He sought to produce music that was challenging, unexpected, and alive: he continually strove after and emphasized excellence (“in composing, in performing, in scholarship, and pedagogy”) and deep musicality to ensure that the technology would not get in the way of artistic creativity nor “suck the fun out of making music.”[5] Matt Barber, an Eastman alum (MA 2008, PhD 2015) who studied with Schindler and worked with him in the ECMC, aptly summarized Schindler’s compositional philosophy in a memorial tribute to his teacher and mentor: “Allan was always seeking ways of creating music which—as he put it—‘makes you happy to be alive.’”[6]

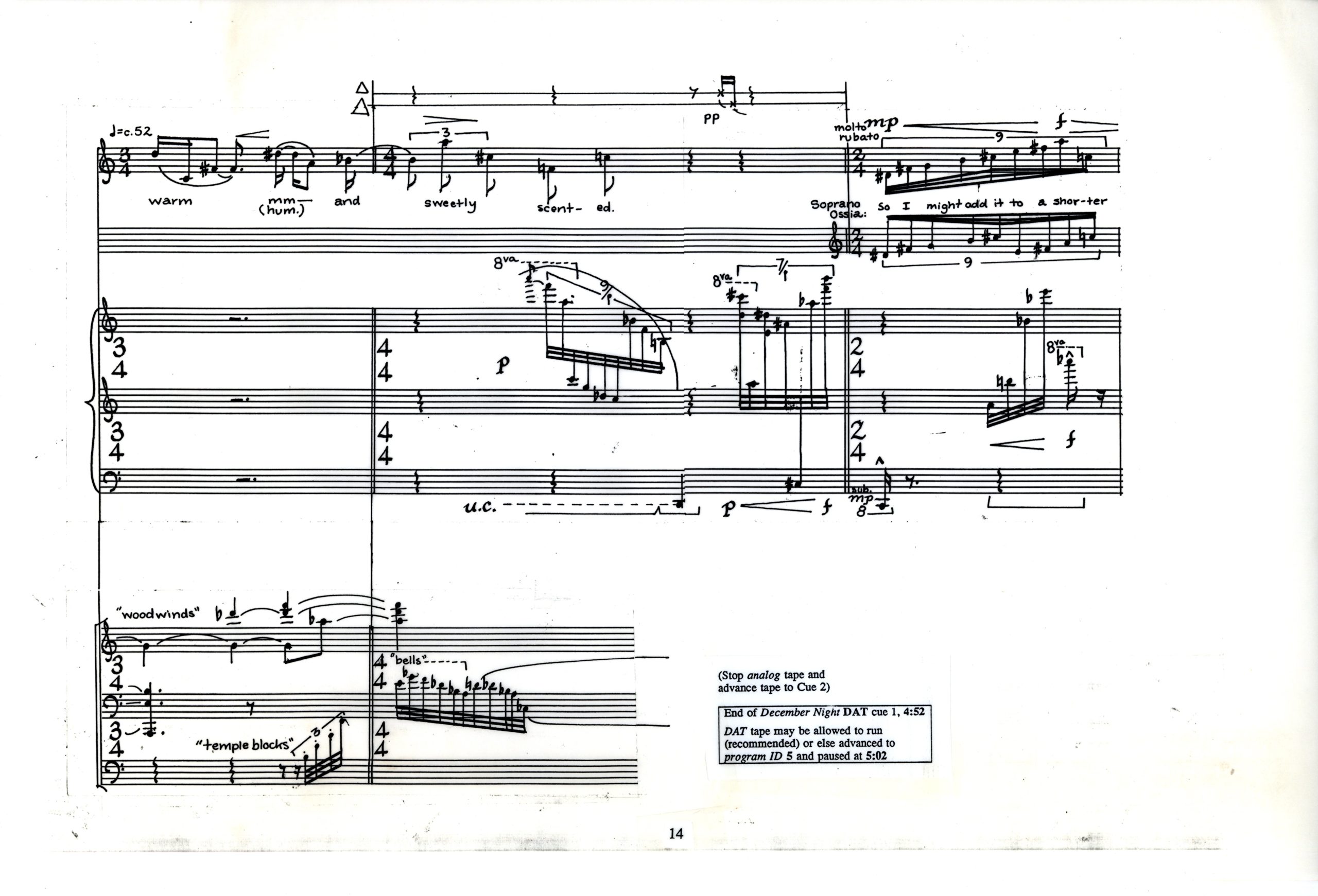

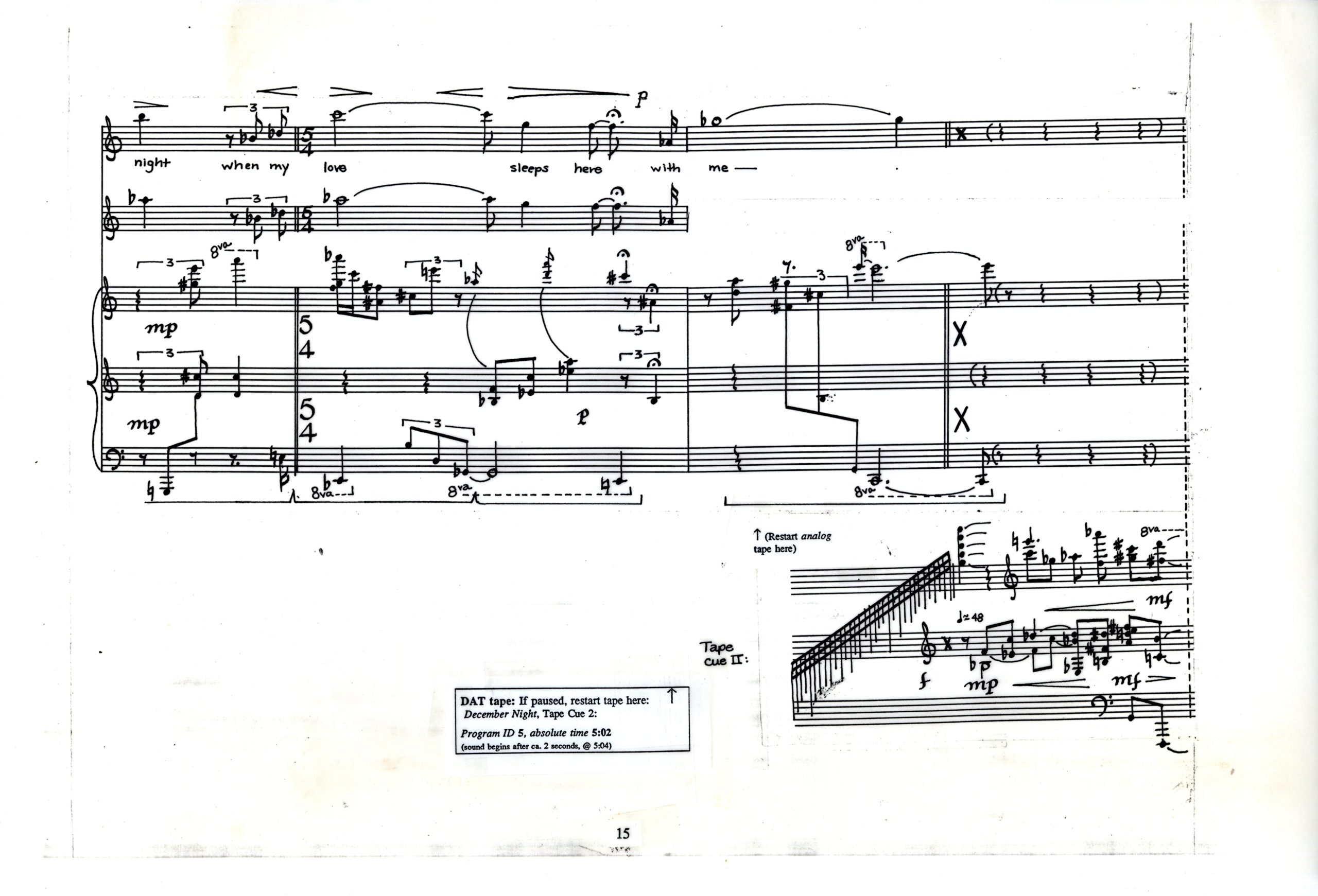

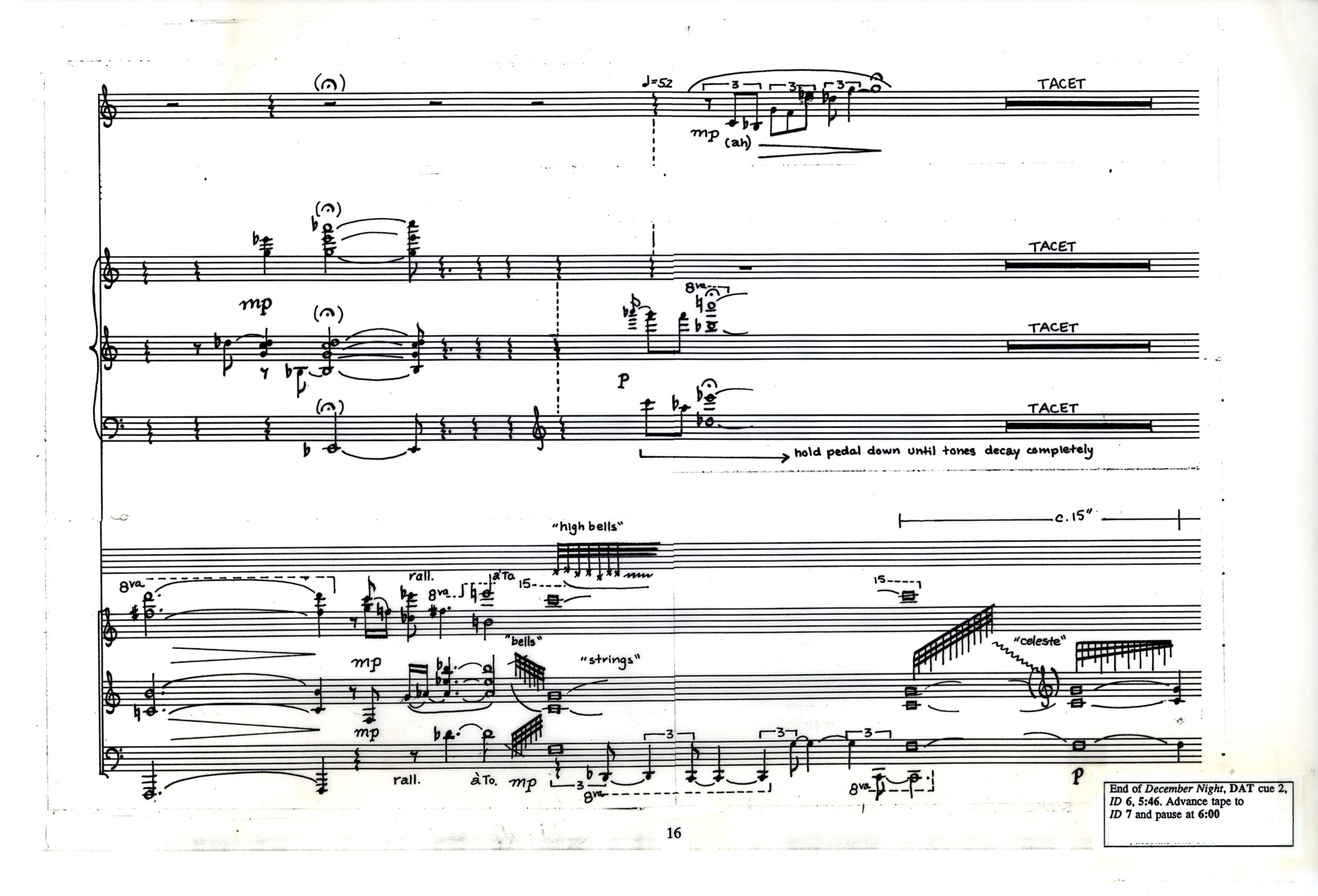

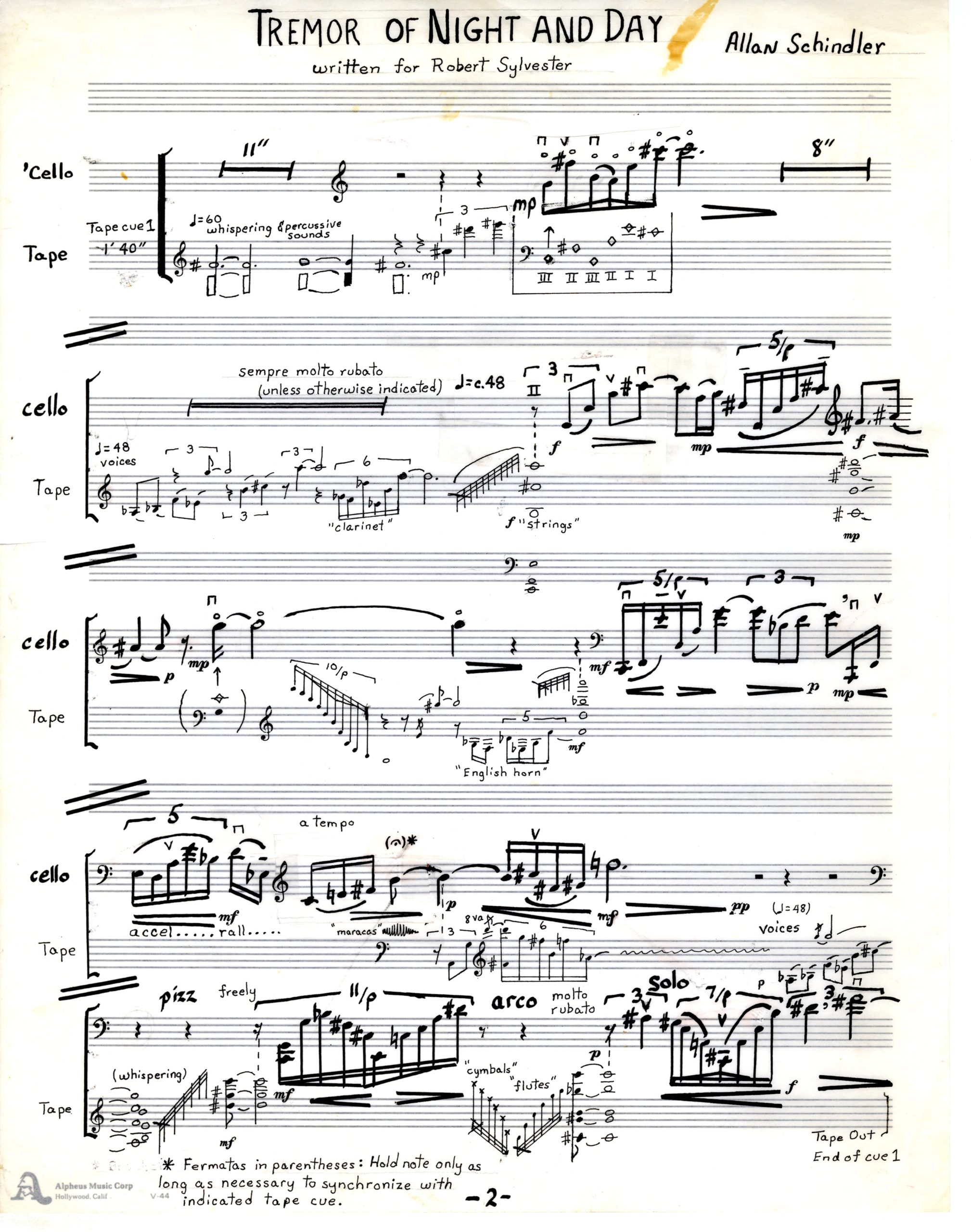

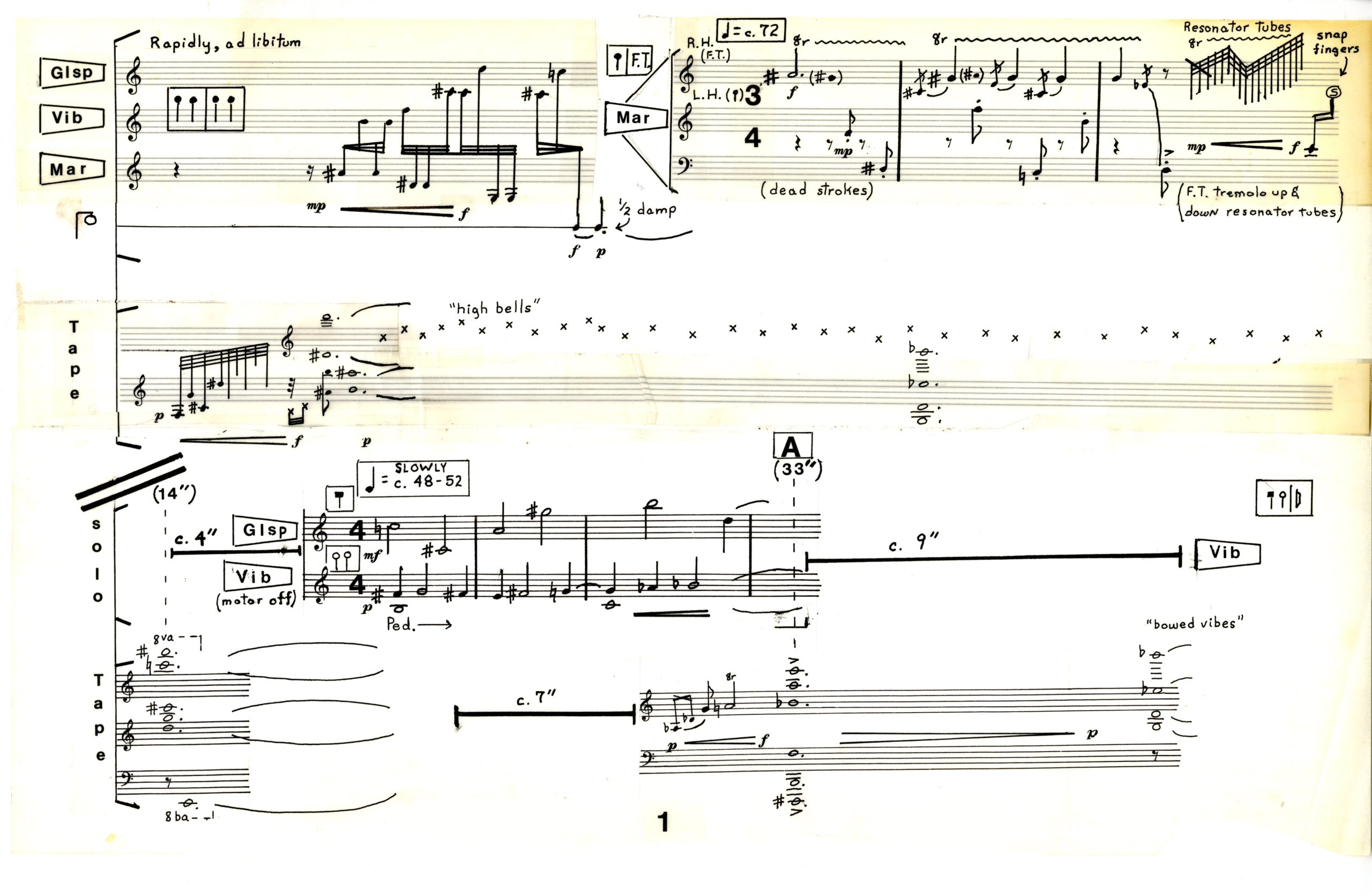

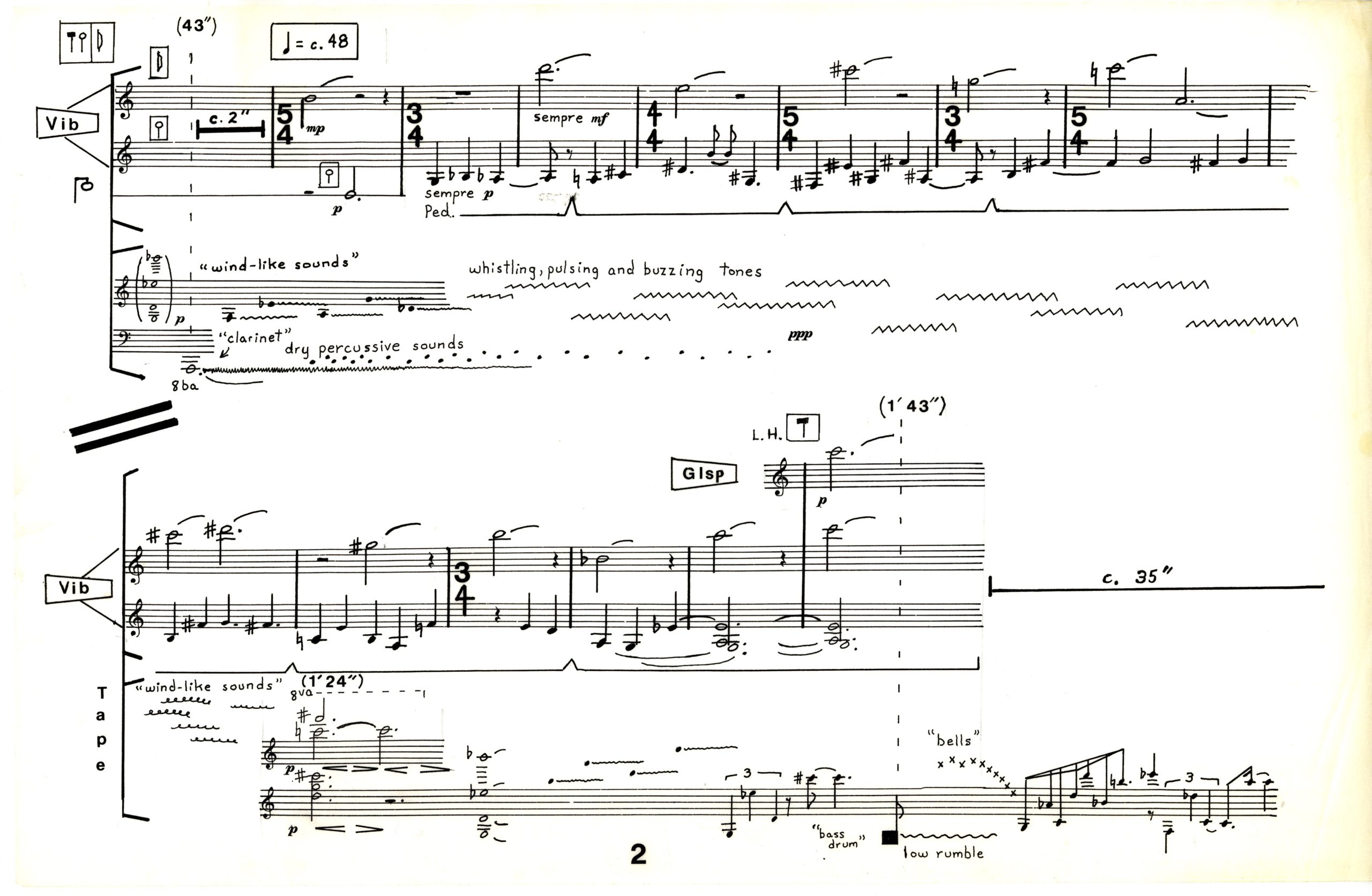

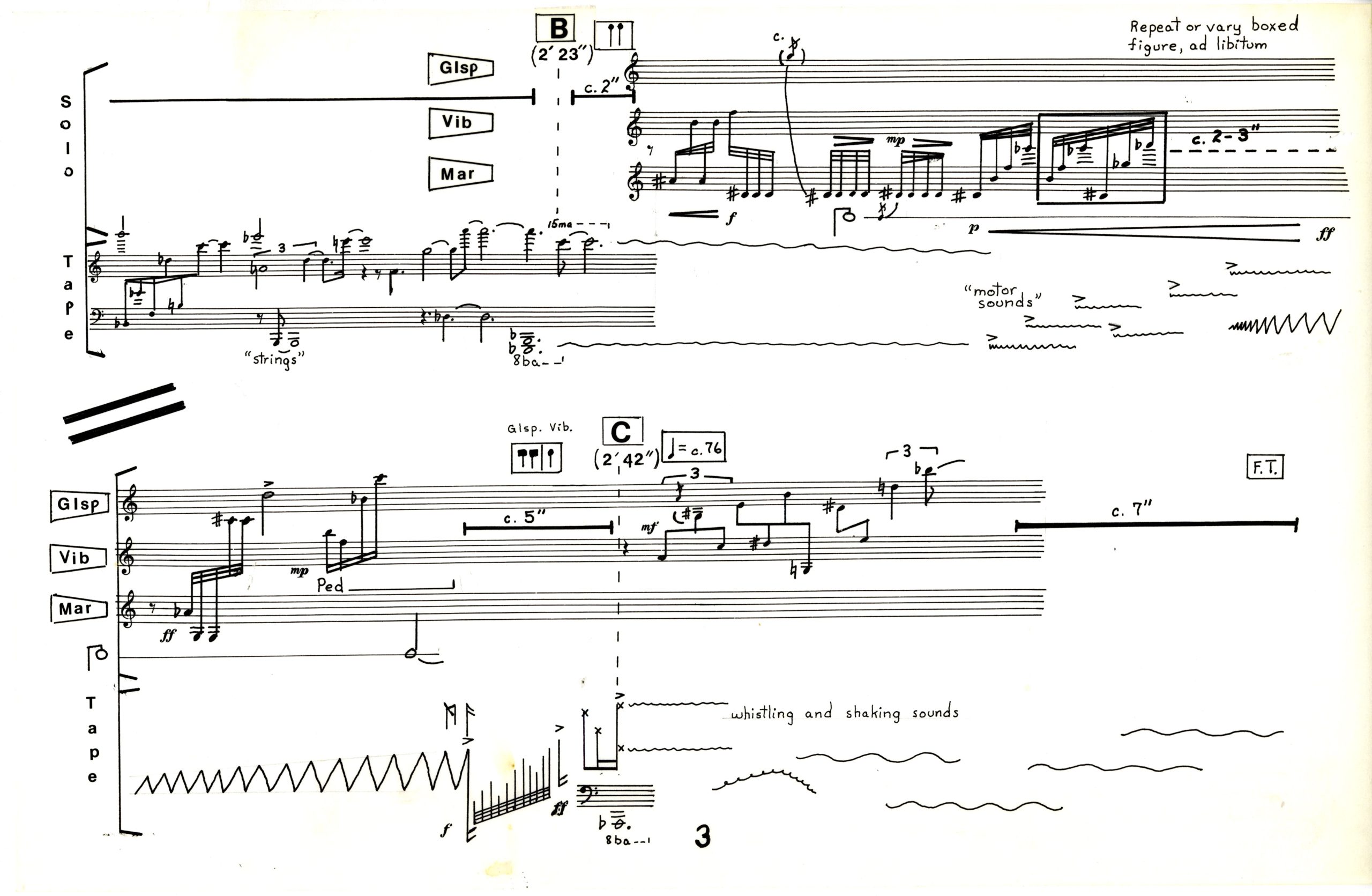

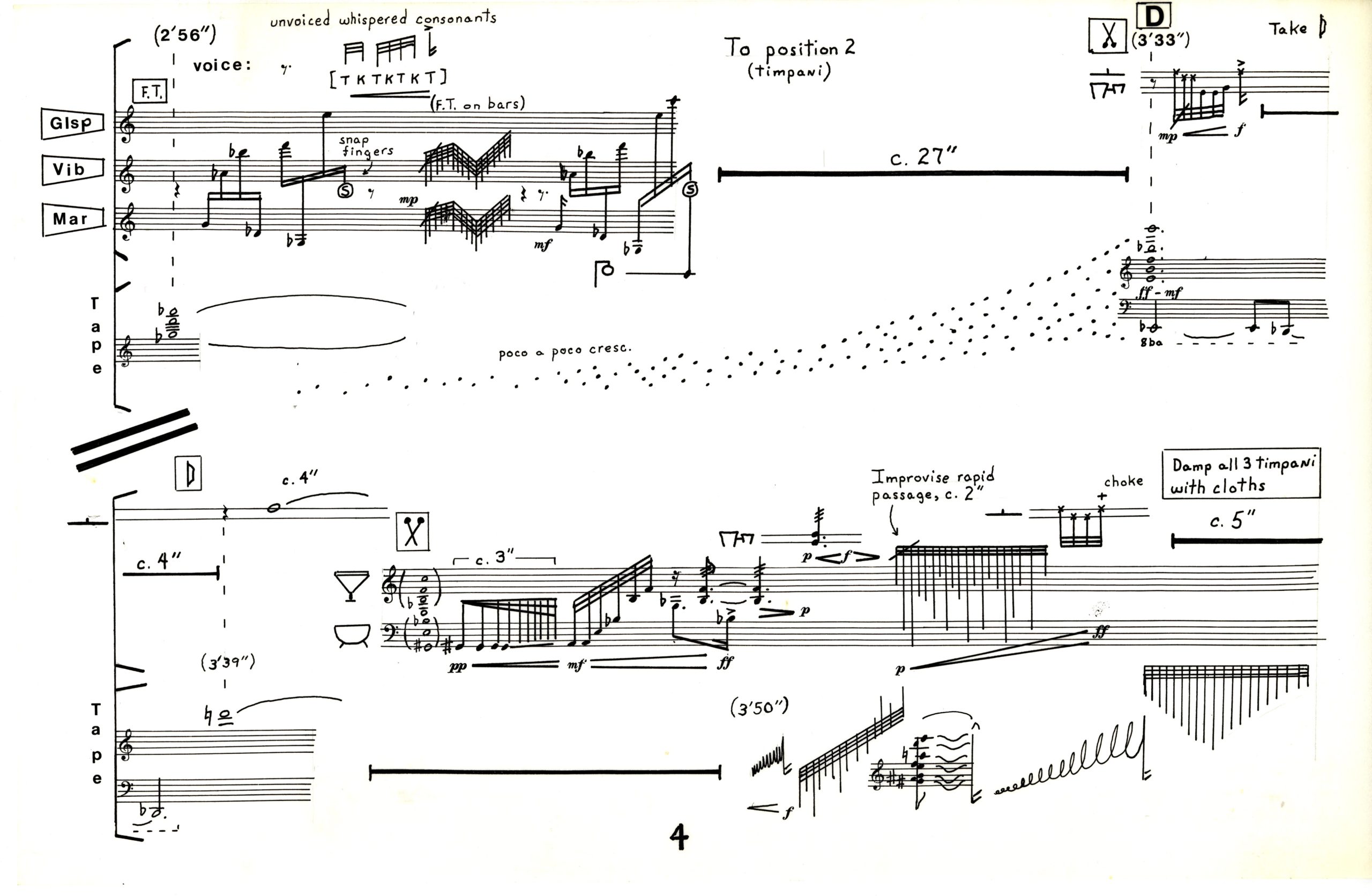

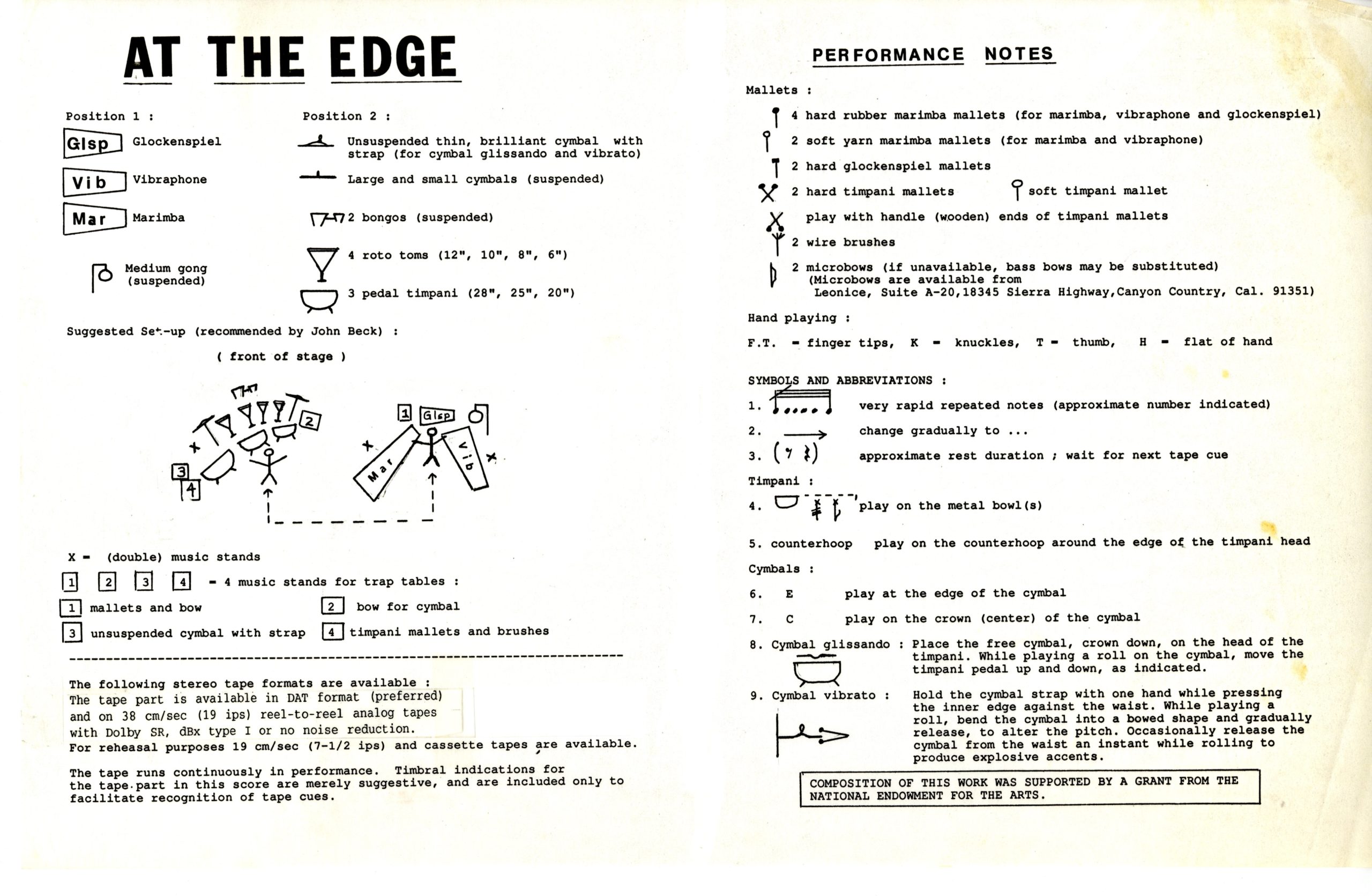

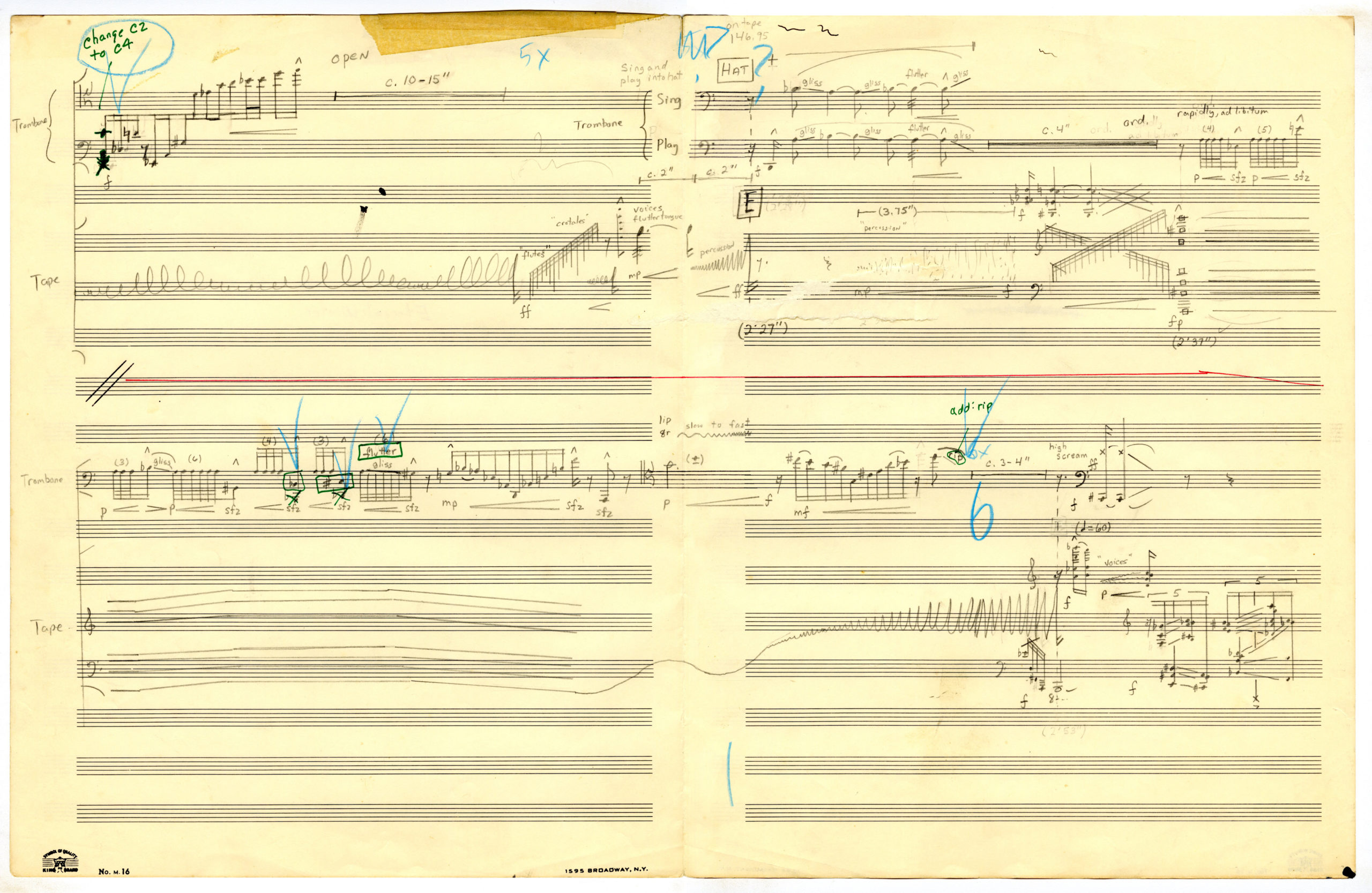

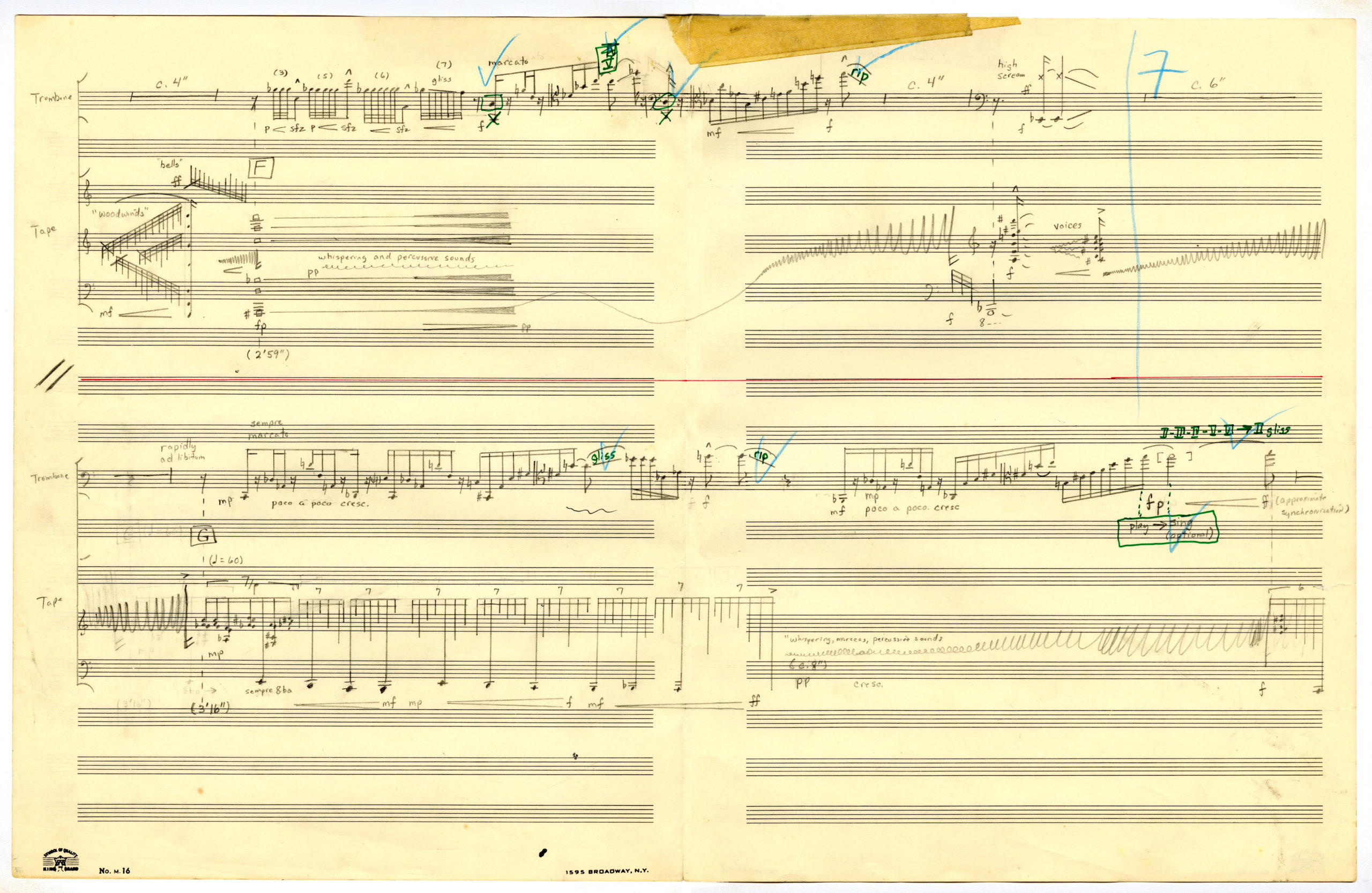

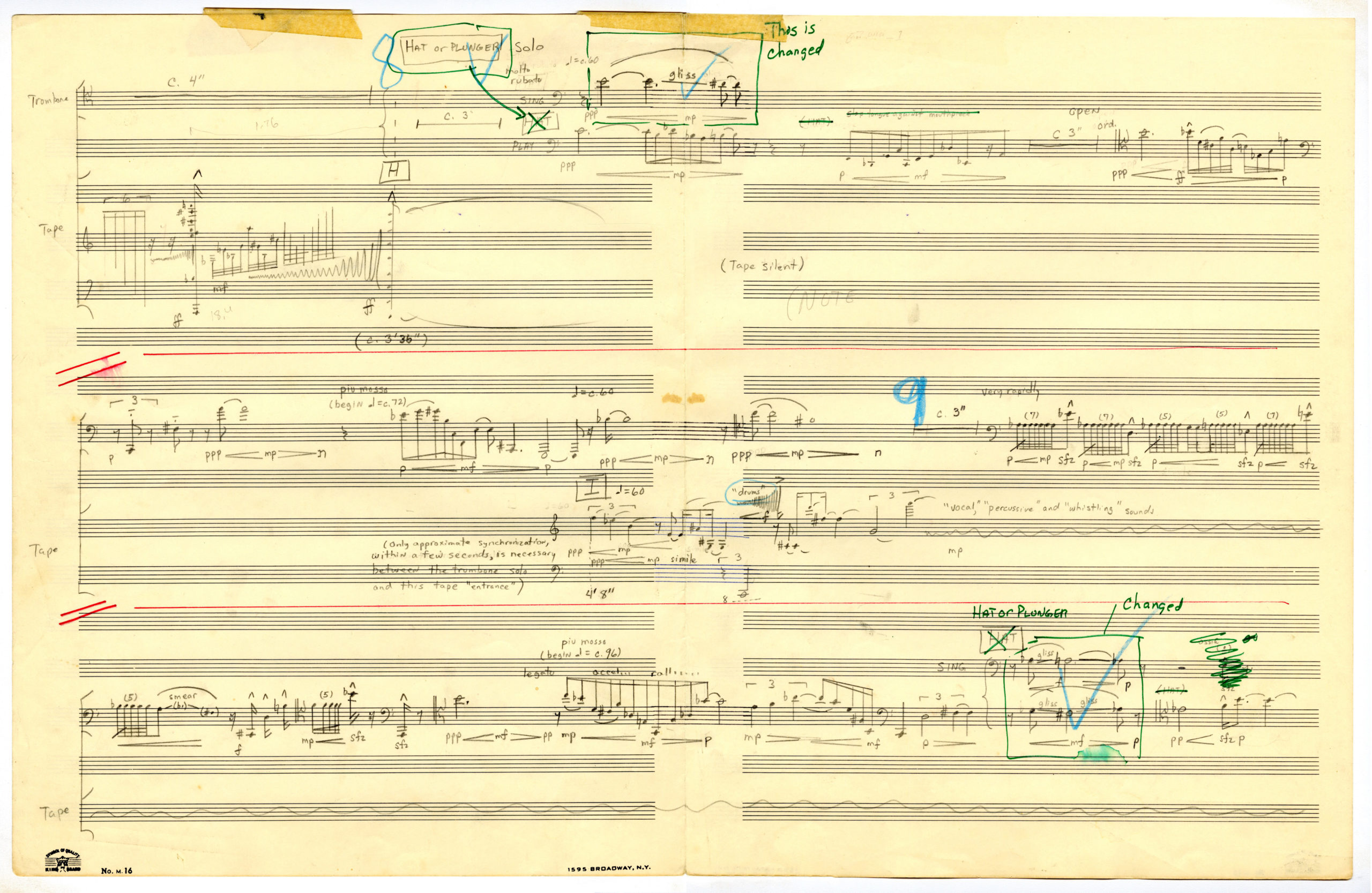

One especially successful approach—which Schindler applied in many of his own composition projects as did many other ECMC composers—was collaboration between composers and performers. This included numerous works that were commissioned by or written expressly for Eastman faculty performers. In the 1980s, Schindler produced three such pieces: Tremor of Night and Day (1984), which was commissioned and premiered by Robert Sylvester (Professor of Cello at ESM from 1975–1986); Eternal Winter (1986), written for and premiered by John Marcellus (Professor of Trombone at ESM from 1978–2014); and At the Edge (1989), commissioned by John Beck (Professor of Percussion at Eastman from 1959–2008).

7

A key tenant of Schindler’s compositional aesthetic, especially in his later electroacoustic works, was what he called “defining sounds”—that is, “pitch or rhythmic motives, sonorities, or chords that are associated with a unique or particular timbre and that recur prominently in varied form and different contexts during a work.” His solo for percussionist John Beck, At the Edge (1989), for example, grew out of two such musical ideas, the first being a rhythmically explosive figure inspired by Professor Beck’s highly charged and meticulous performance style, which the composer juxtaposed against a more distant, chorale like phrase.

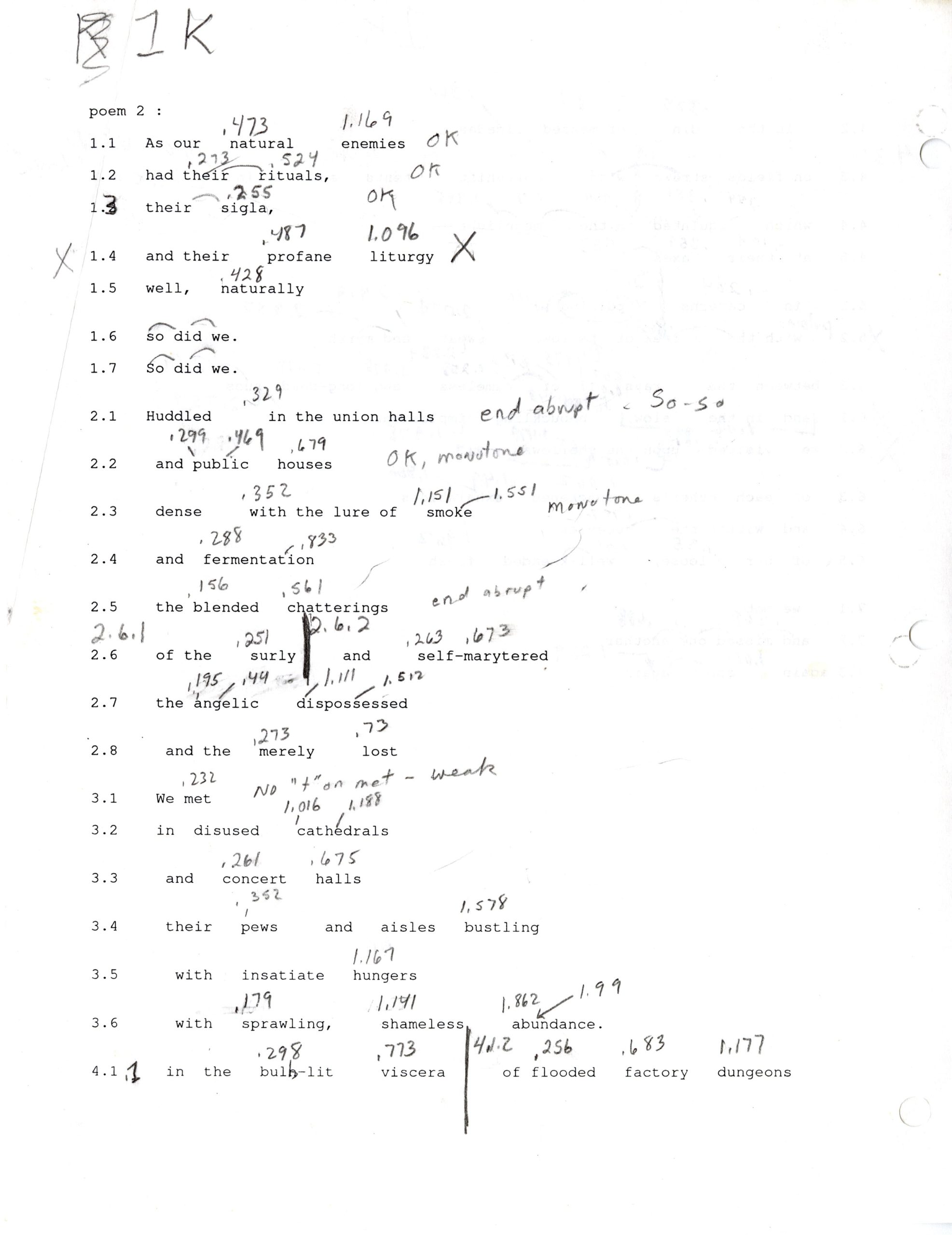

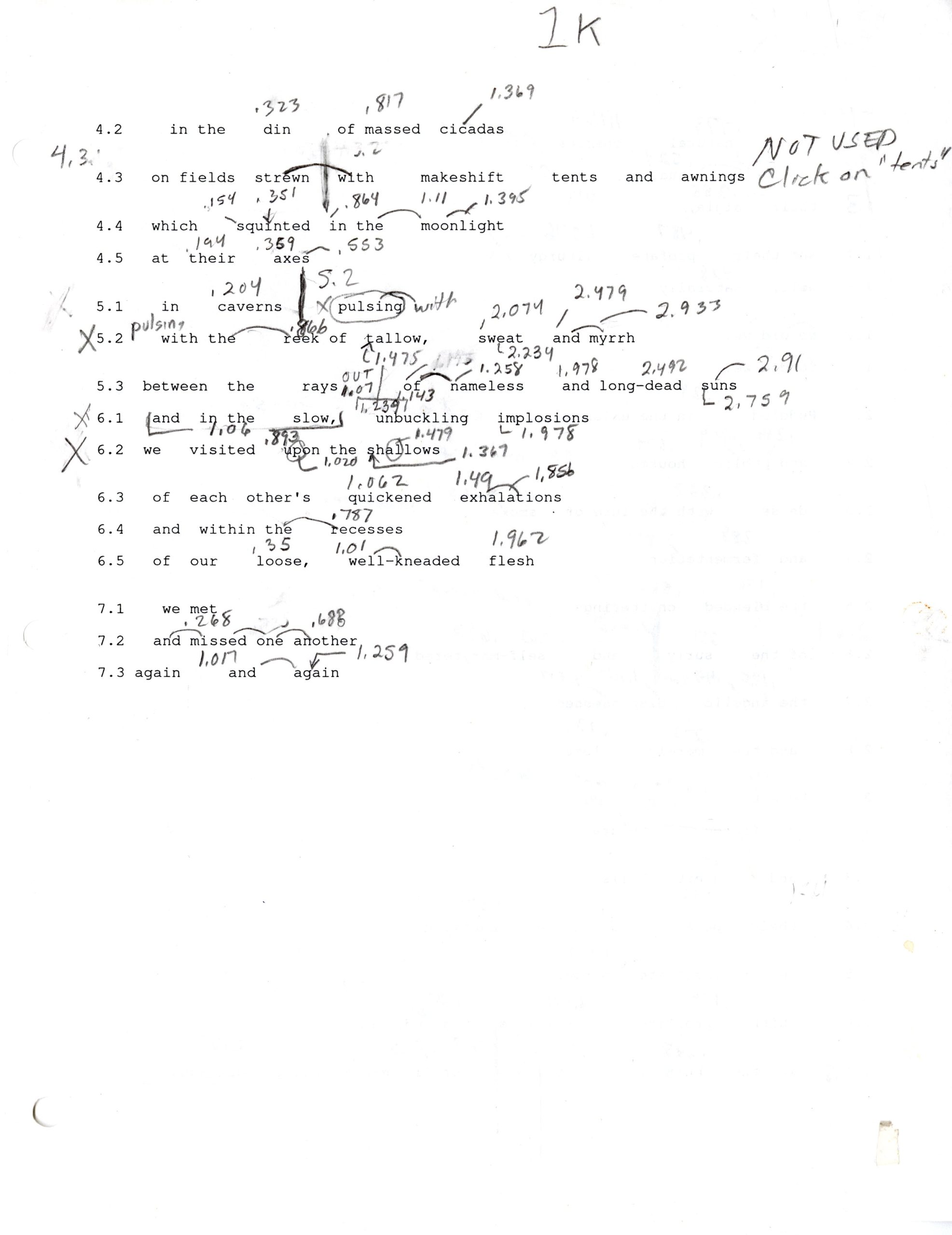

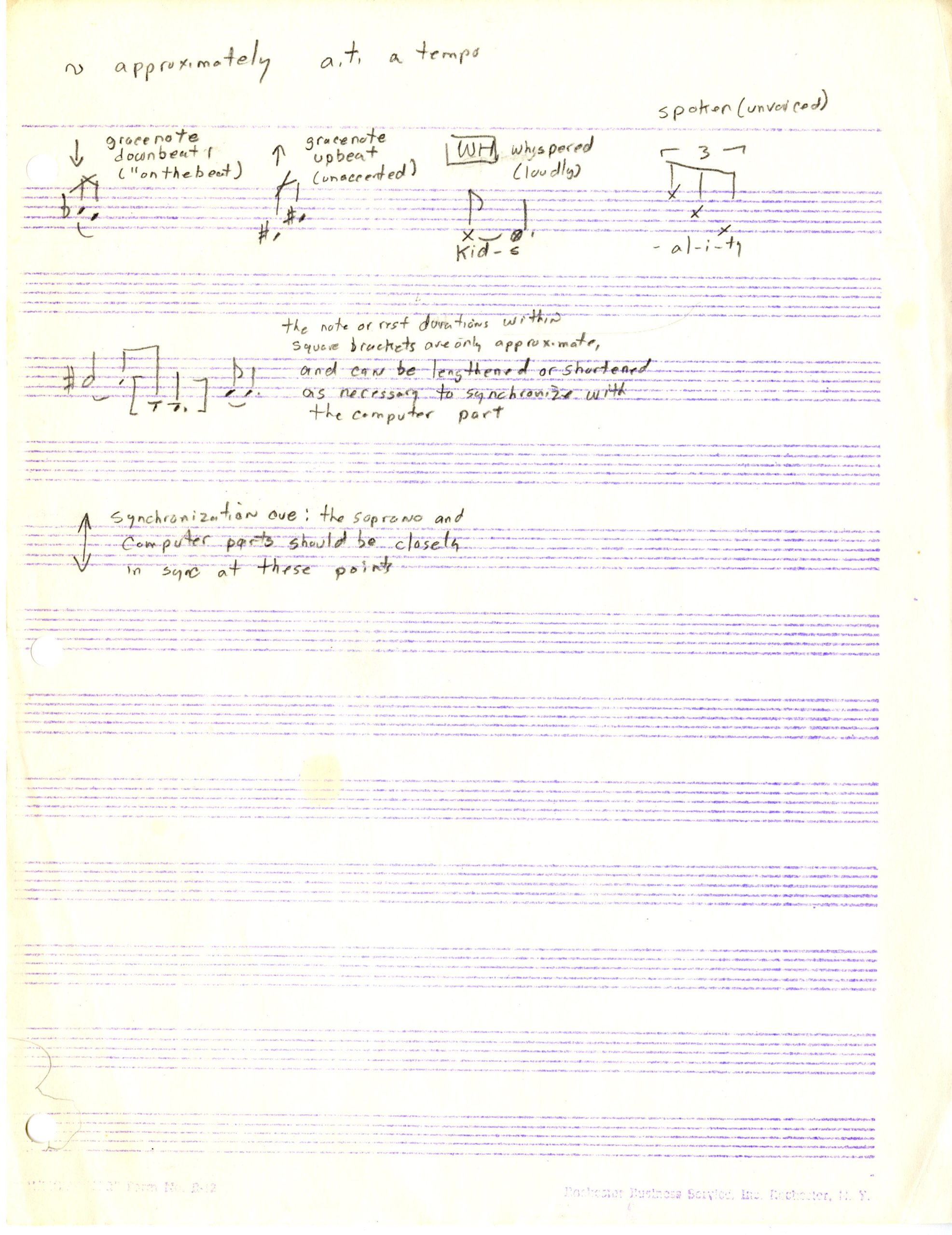

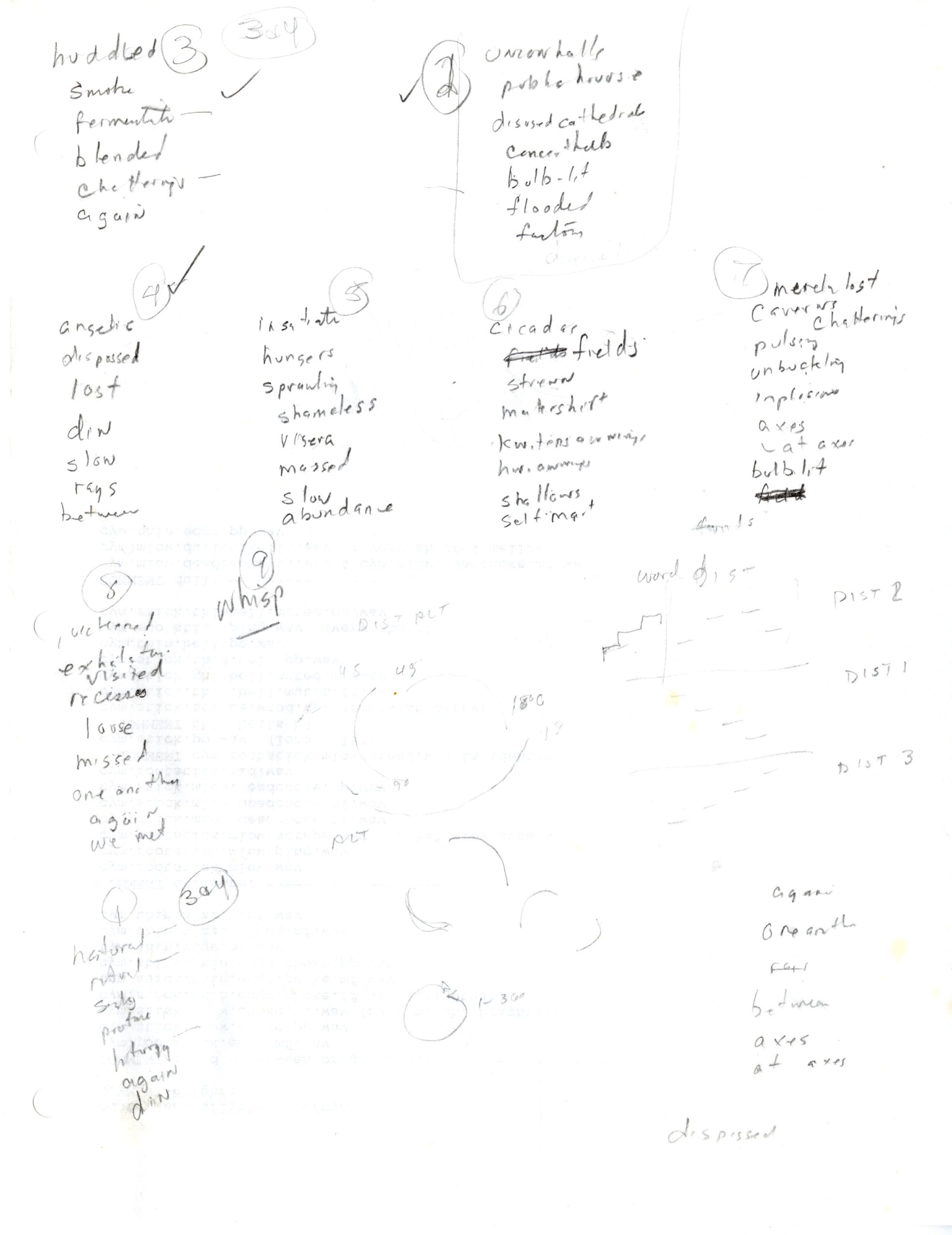

In a short essay published on his personal website, Schindler extrapolated on the techniques he would employ to create and combine these “defining sounds” using specific examples extracted from his 2005 composition Diaspora for soprano and computer-generated sounds, which he wrote for soprano Heather Gardner, an ardent performer of contemporary music who had recently graduated from Eastman.[7] The two poems used in the piece (both by Kenneth Staples) are, in Schindler’s words “dark, lyrical and richly textured in metaphorical associations, often considering such issues as lost opportunity, unfulfilled promise and disregard, societal as well as individual.” In setting the texts, Schindler constructed the computer-generated sounds largely from generic voice samples, which he transformed from bland phonemes and tones into more expressive timbral or pitched thematic material. The most prominent defining sound in Diaspora was created from a bass choir tone, which Schindler manipulated by deleting or shifting several of the original, acoustic tone’s frequencies or harmonics to create a timbre that sounded “somewhat like a ‘shadow’ of the source sound”: the resulting sound retained some of the recognizable qualities of the original tone but the digital manipulation bestowed it with “a new musical definition or ‘feel.’” Schindler then treated these defining sounds like chords, combining them to create “progressions” that would accompany, support, interact with, and punctuate the vocal solo. In the completed composition, each of the defining sounds is carefully introduced, varied, and developed throughout the piece in new combinations or “associations” to great expressive effect.

8

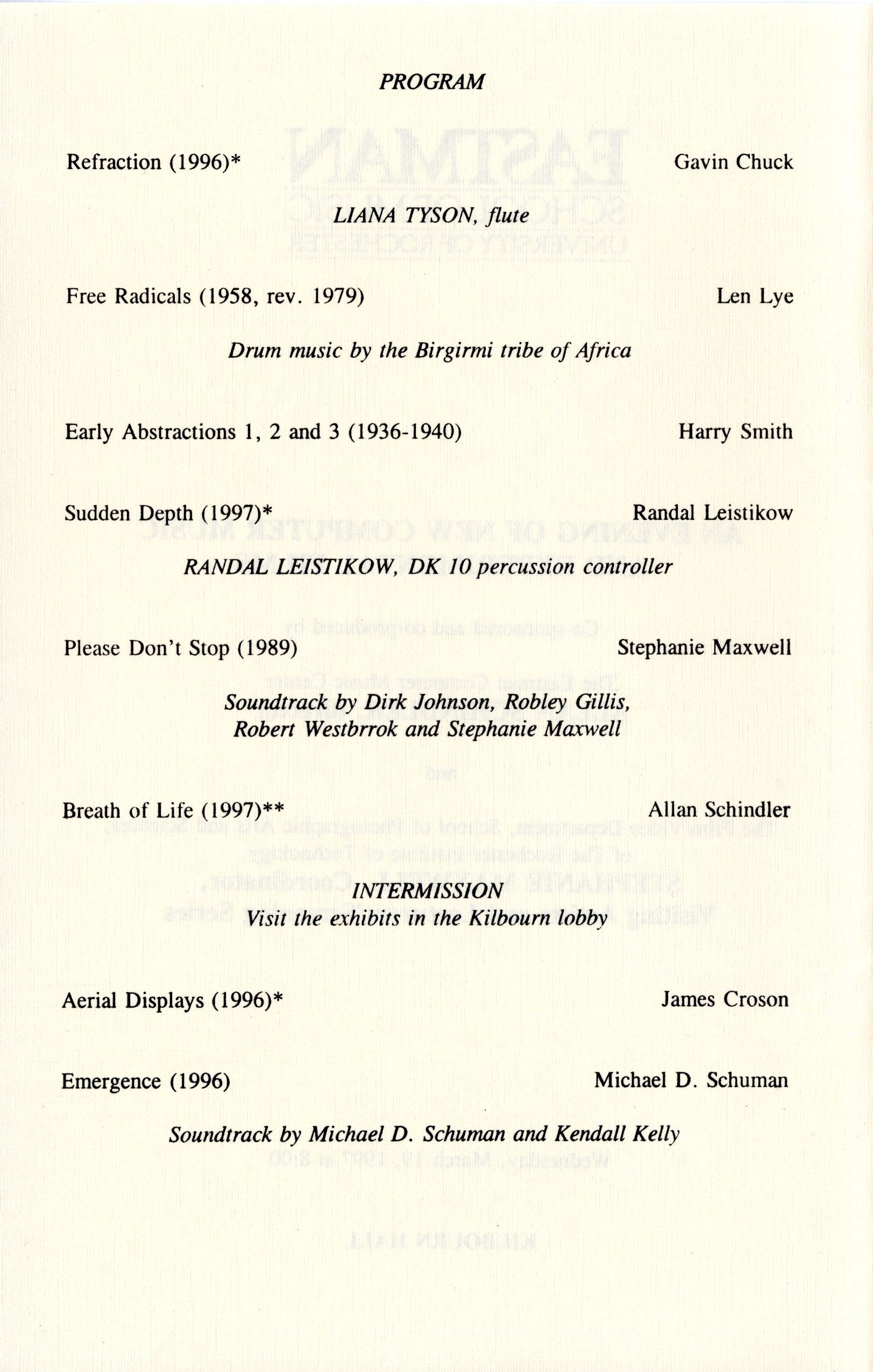

In March 1997, Schindler and the ECMC, working with Stephanie Maxwell, an independent filmmaker and Associate Professor in the Rochester Institute of Technology’s Film/Video Department, organized “An Evening of New Computer Music and Experimental Films” as a showcase for new and innovative works by students and faculty from both institutions. The collaboration proved to be an incredible success. The next year, with SUNY Brockport joining as a third institutional co-sponsor, the event was relaunched as ImageMovementSound, an annual festival of multimedia collaborative works by students and faculty from the participating institutions. Over the festival’s twelve years (1997–2008), teams of filmmakers, graphic and media artists, musicians, composers, choreographers, dancers, and artists from other disciplines conceived and realized more than 100 innovative creations that integrated multiple art forms, many of which went on to win awards at international festivals and competitions. The works often integrated experimental performance and production techniques from each discipline as the teams of creators explored the technical and aesthetic possibilities of their individual and combined artistic media.

9

Further, Schindler’s work with ImageMovementSound—and, particularly, his professional collaborations with filmmaker Stephanie Maxwell—expanded his compositional oeuvre into a new multimedia genre that the composer termed “collaborative image/music composition” or (more simply) “film/music composition.” In these experimental, multimedia works, Schindler explained, “structural design, textural patterns, and expressive gestures and nuances unfold simultaneously, but not always synchronously, in aural and visual form,” the music and images contributing “equally to an aggregate, multi-threaded structural and expressive design.”[8]

Between 1998 and 2010, Schindler produced ten film/musical compositions in collaboration with Stephanie Maxwell, Peter Byrne, Carole Woodlock, and Tom Gasek. The structural designs of these compositions were typically non-narrative, non-linear, abstract, and continuous, in a process that enabled all collaborators “to exercise full creative freedom in devising patterns of sound and visual imagery and color, but also to play off each other’s ideas, to extend, comment upon, reinterpret, and enrich these ideas, and ultimately to develop and shape them into a richly textured fabric.” For example, Second Sight (2005)—a collaboration between Schindler, Stephanie Maxwell, and painter/graphic artist Peter Byrne—explored and interrogated the sensory experience of passing through a mist in which perception is ultimately clarified and sharpened rather than obscured. The aural and visual elements of the composition were constructed around a similar foundation of short repeated segments that invited the audience to reassess and interrogate their perceptive experience. In his notes on the composition, Schindler explained:

A prominent and recurring component of the visual imagery in Second Sight consists of short looped segments, in which abstract images twirl, spin or tumble, sometimes in rapid succession. The music, too, includes loop-like segments, but these passages sometimes do not coincide with the visual loops, and they have little in common with the hypnotic iterative procedures heard in much loop-based pop and commercial music. Rather, the loop-based musical passages in Second Sight employ modified repetitions of interlocking motivic ideas, incorporate gradual transformations in pitch and intervallic sets and also incorporate the continuous introduction of new but related timbres as well as irregular cross-accents.[9]

A short excerpt from the film is available for online viewing courtesy of Light Cone, a nonprofit organization whose aim is the distribution, promotion and preservation of experimental cinema in France and around the world.

10

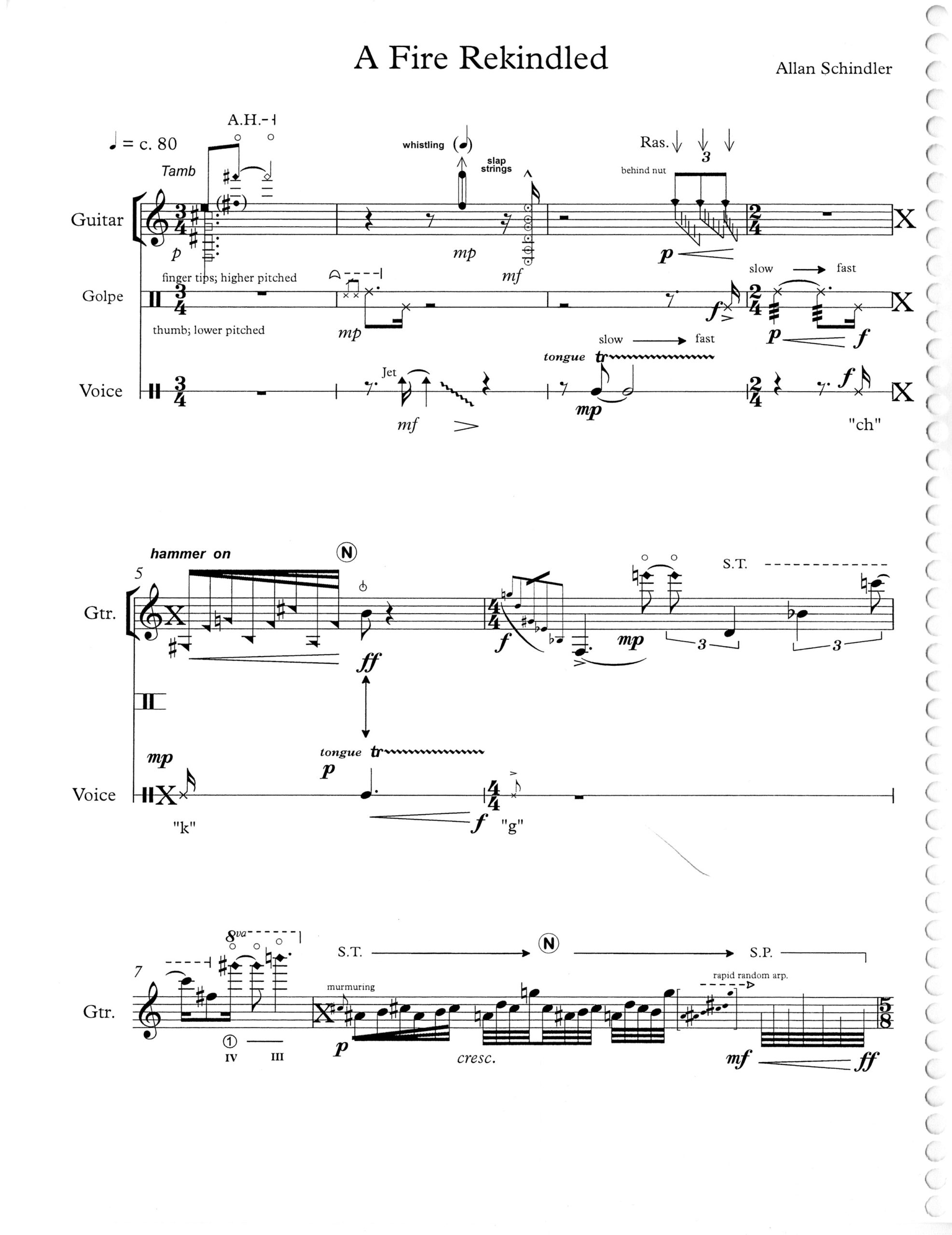

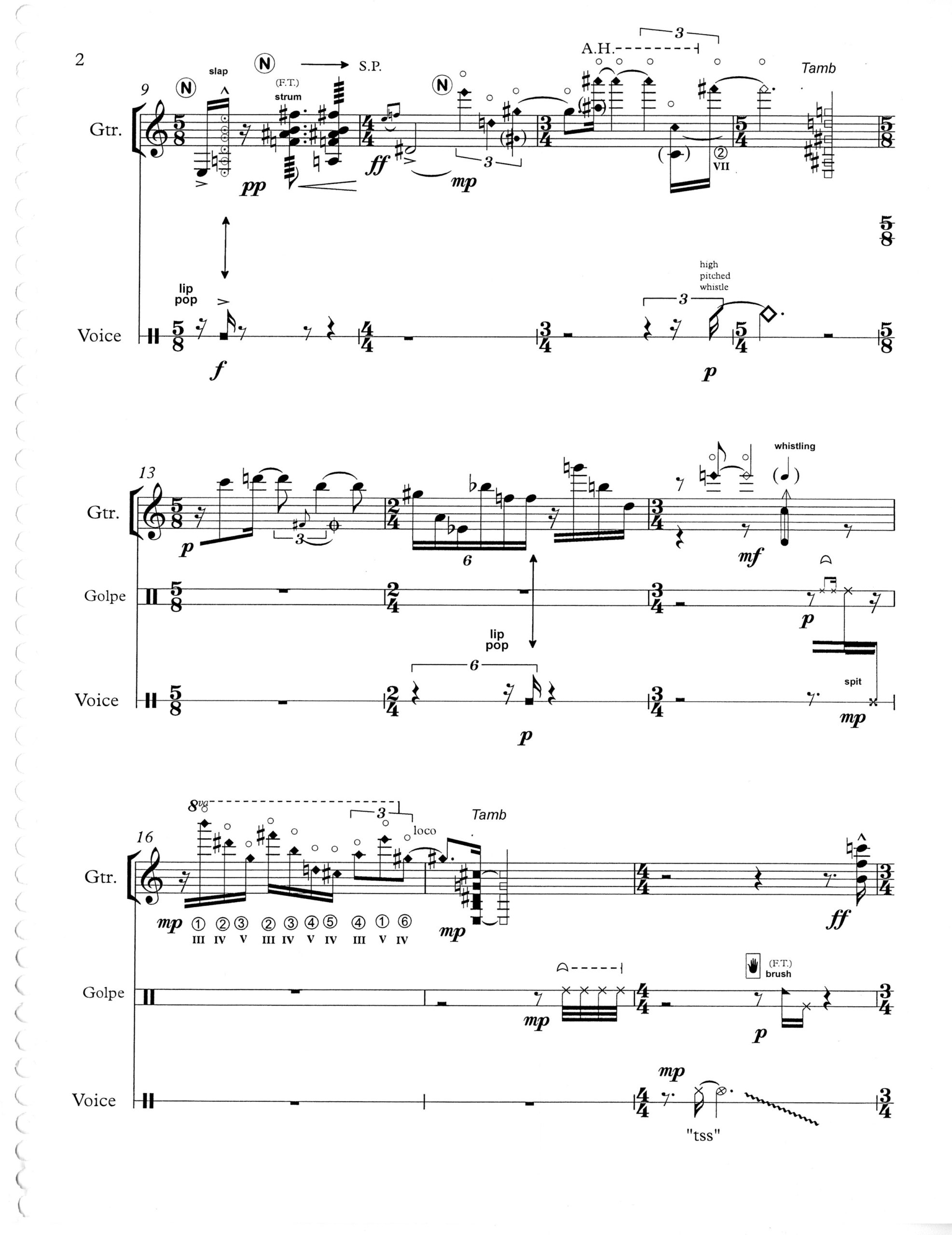

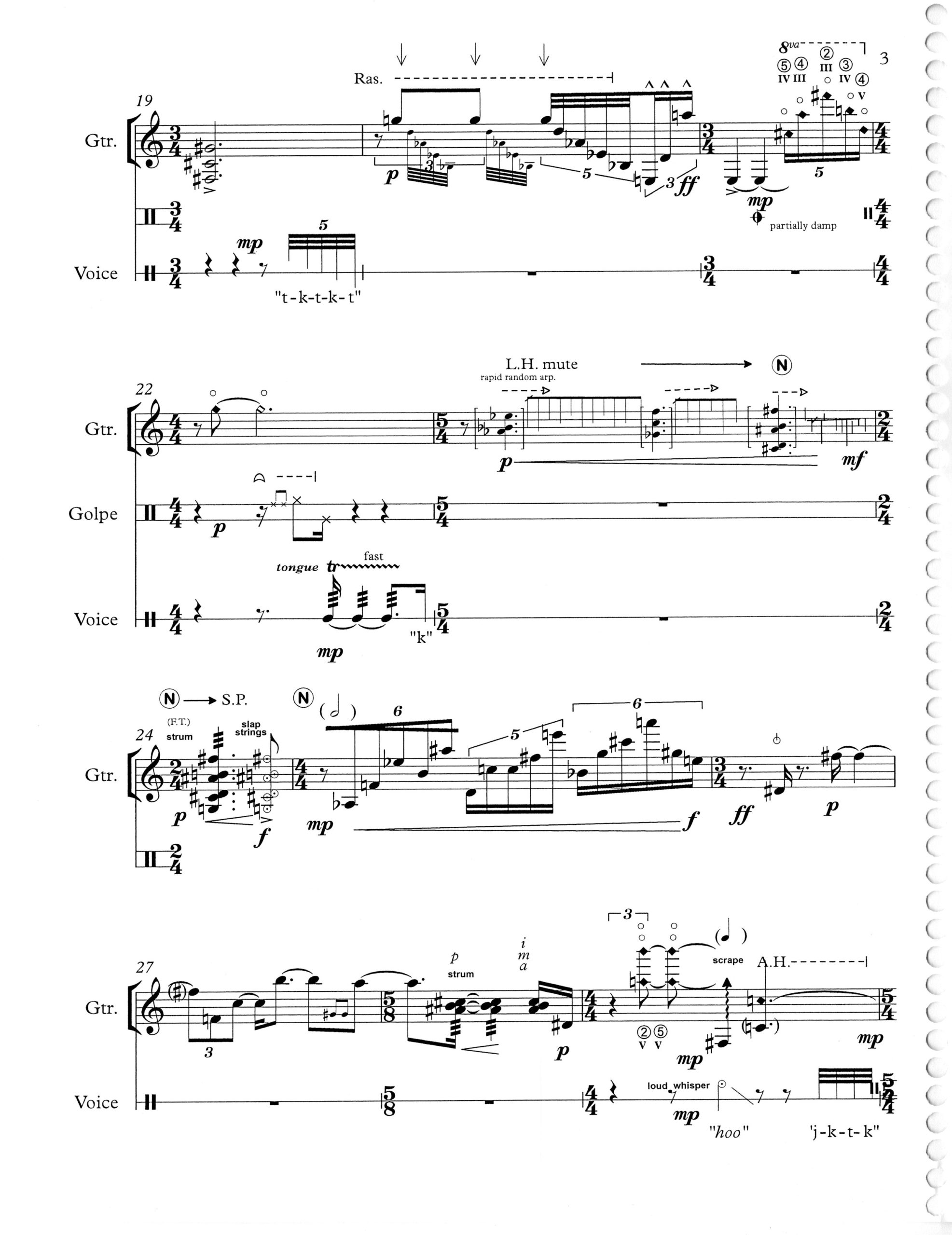

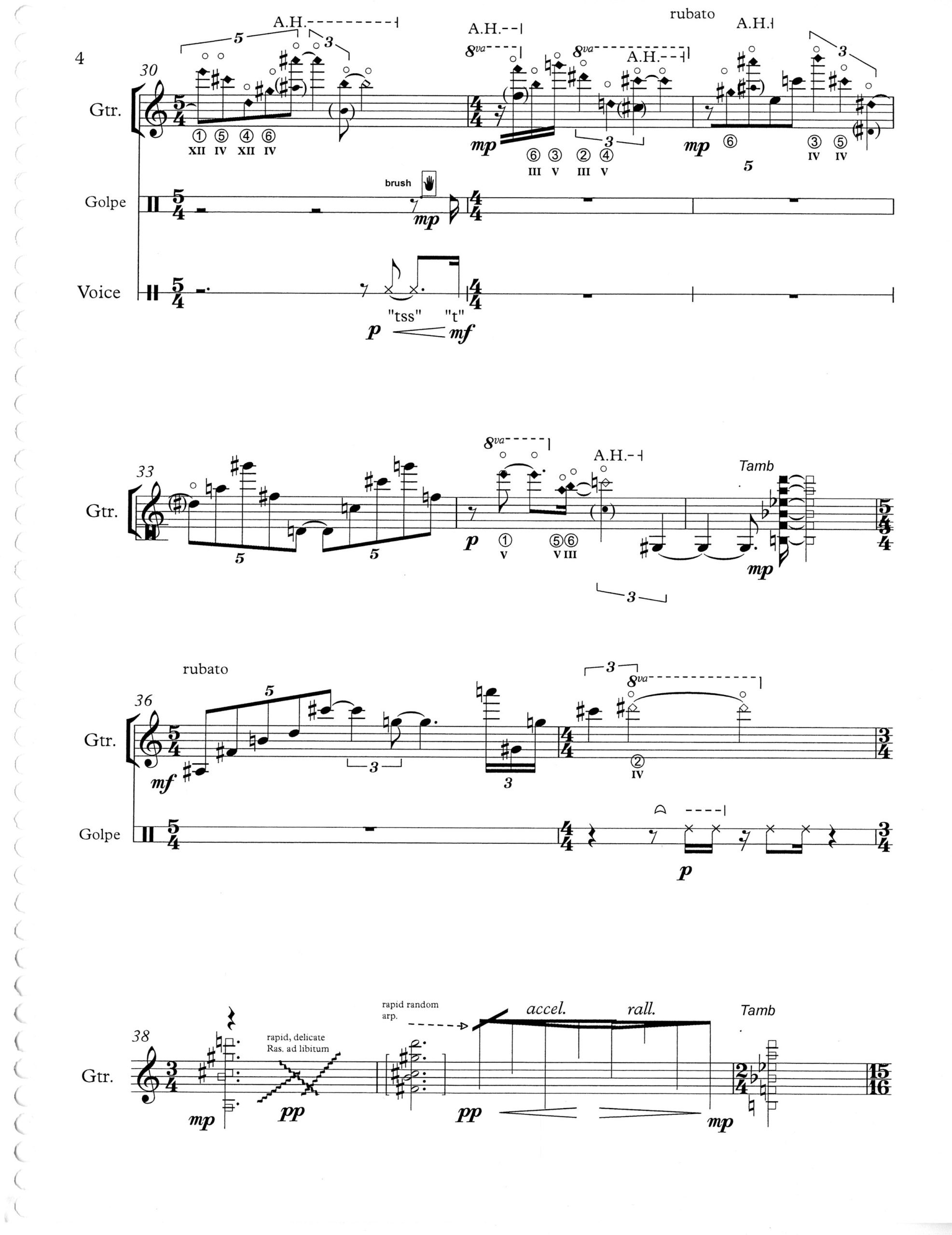

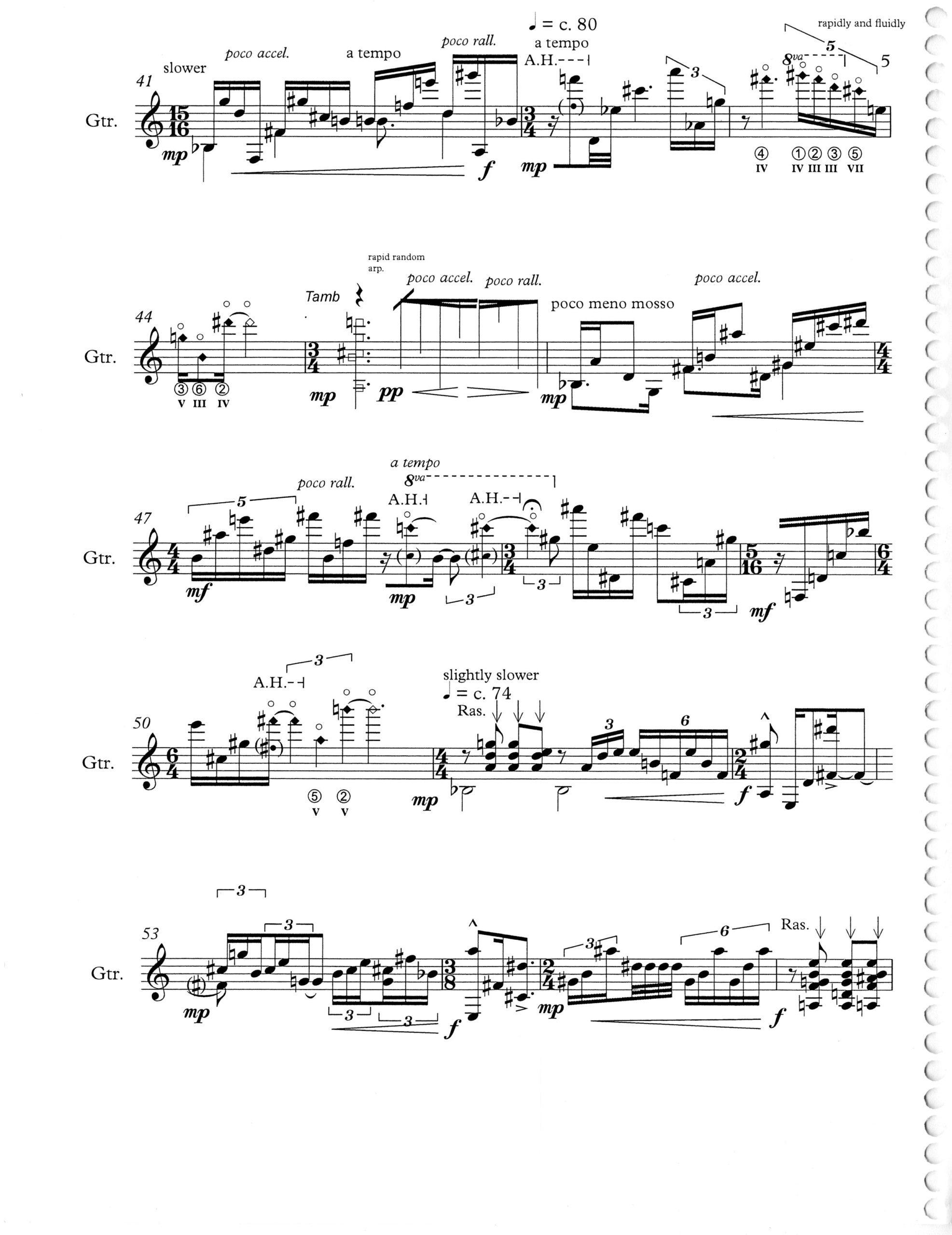

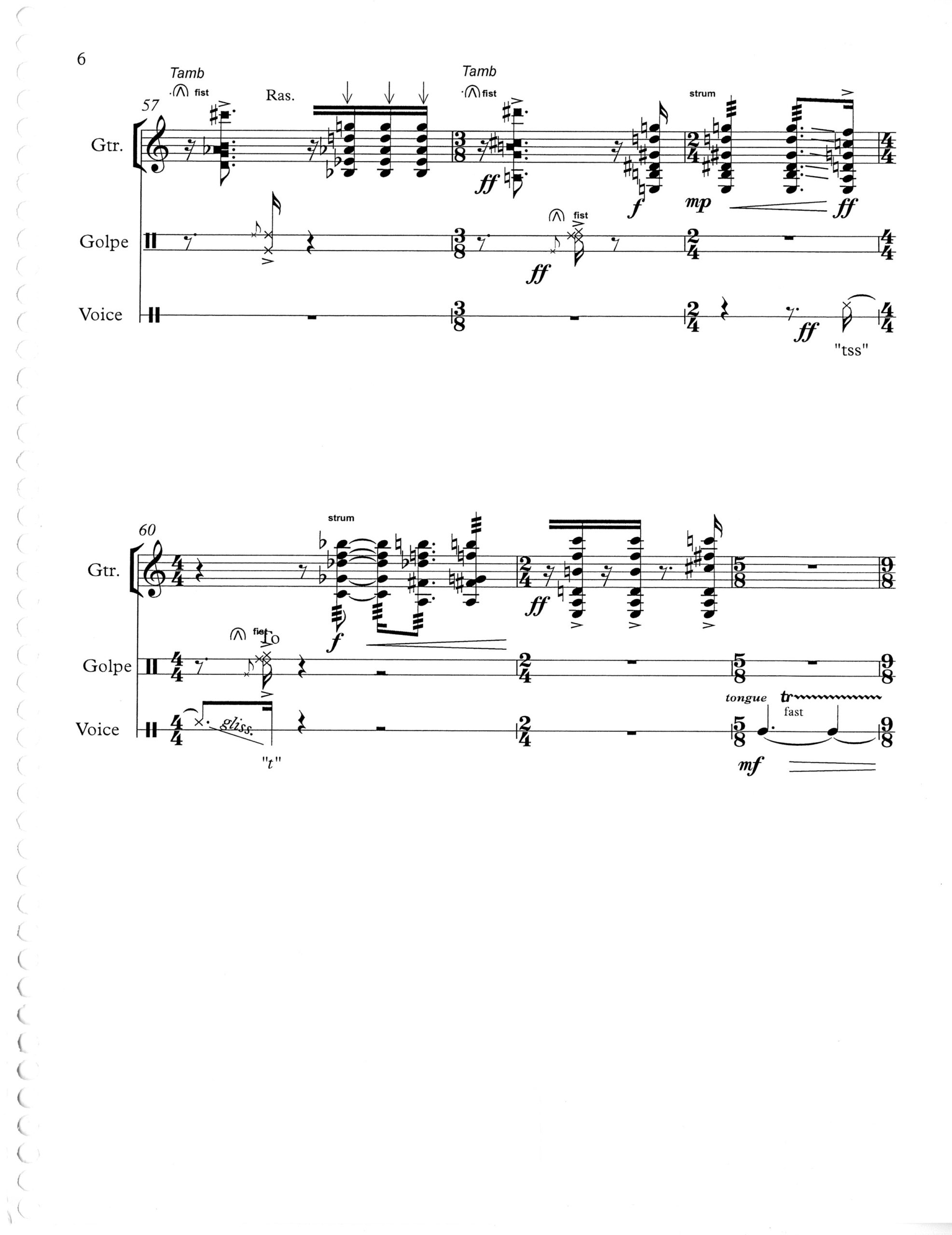

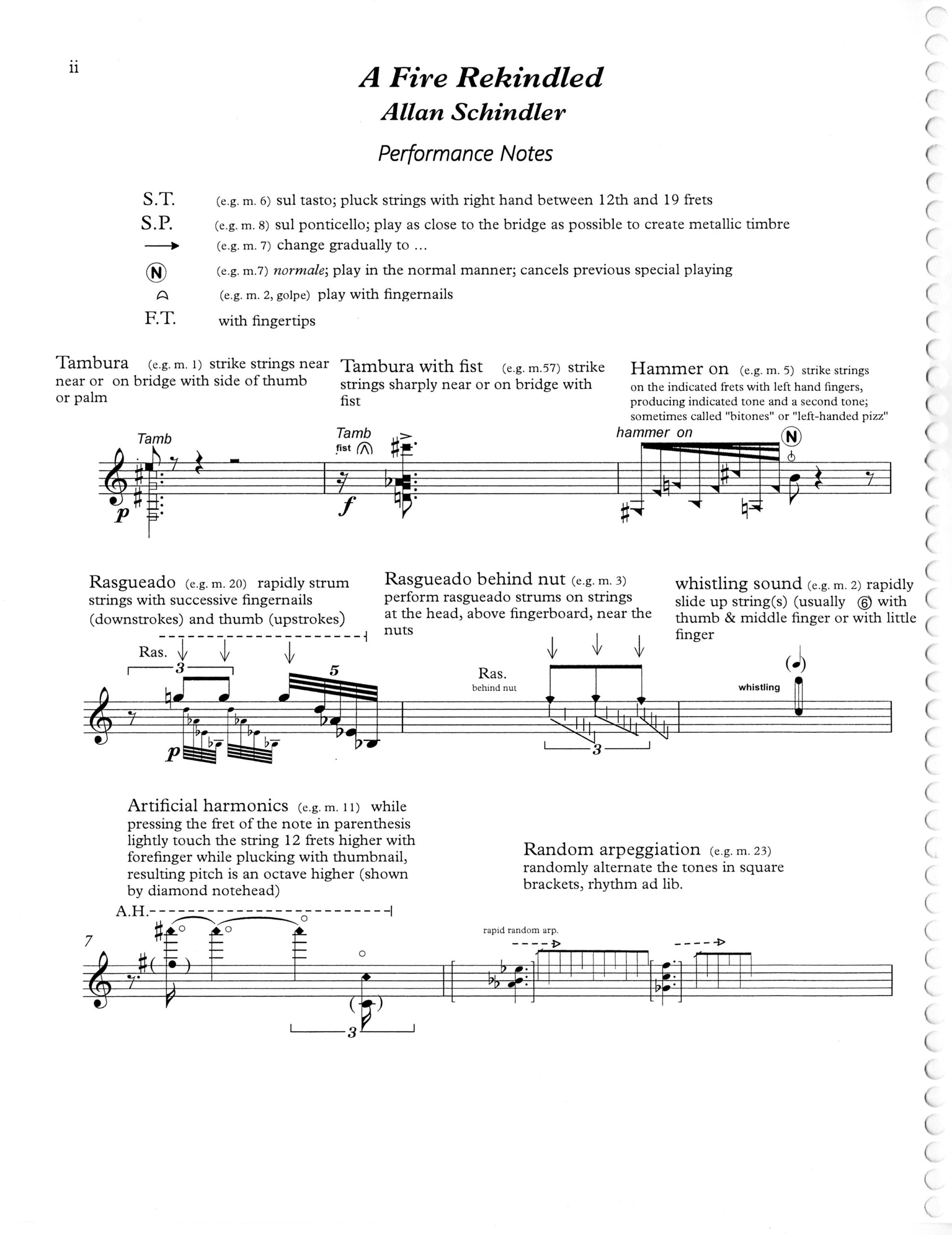

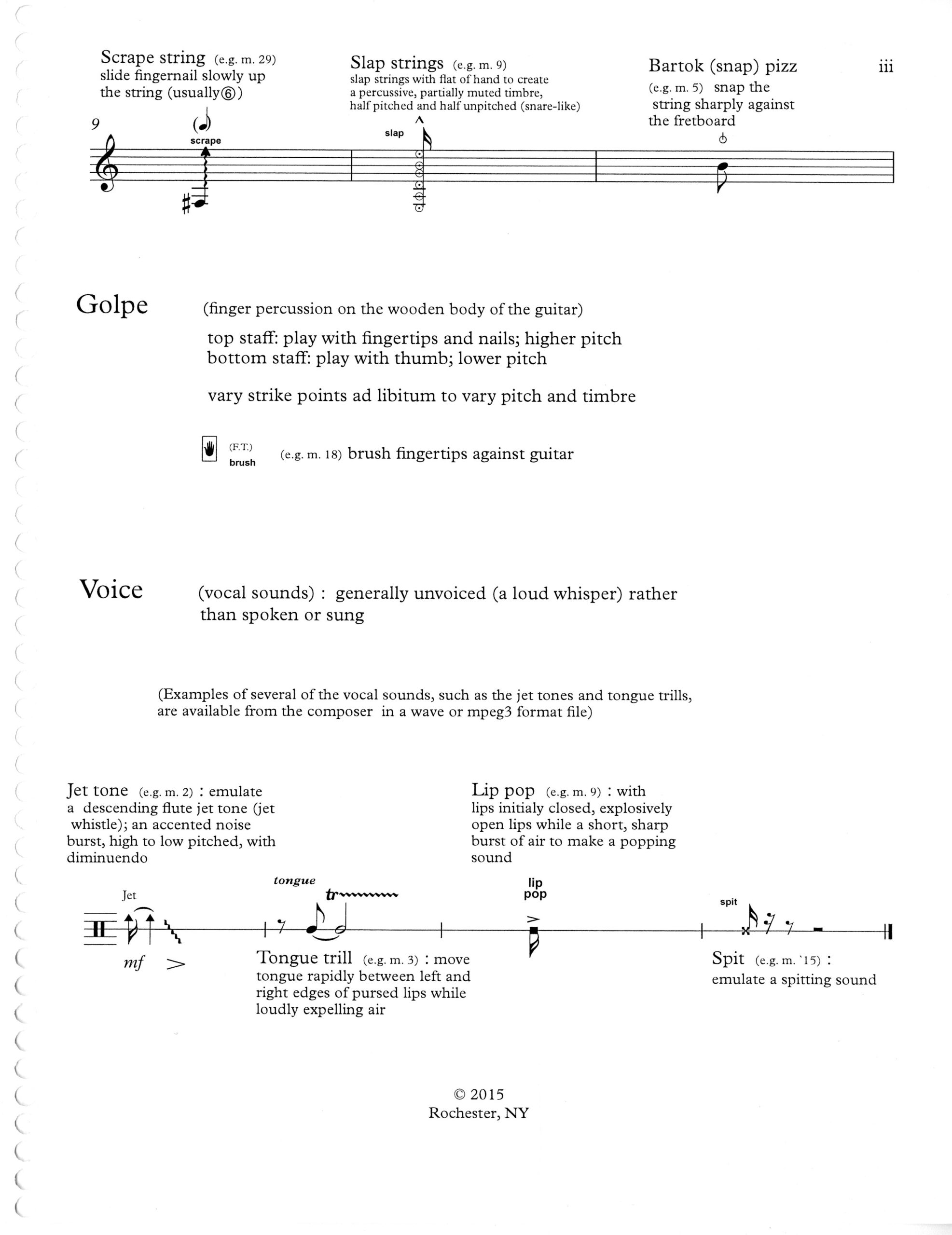

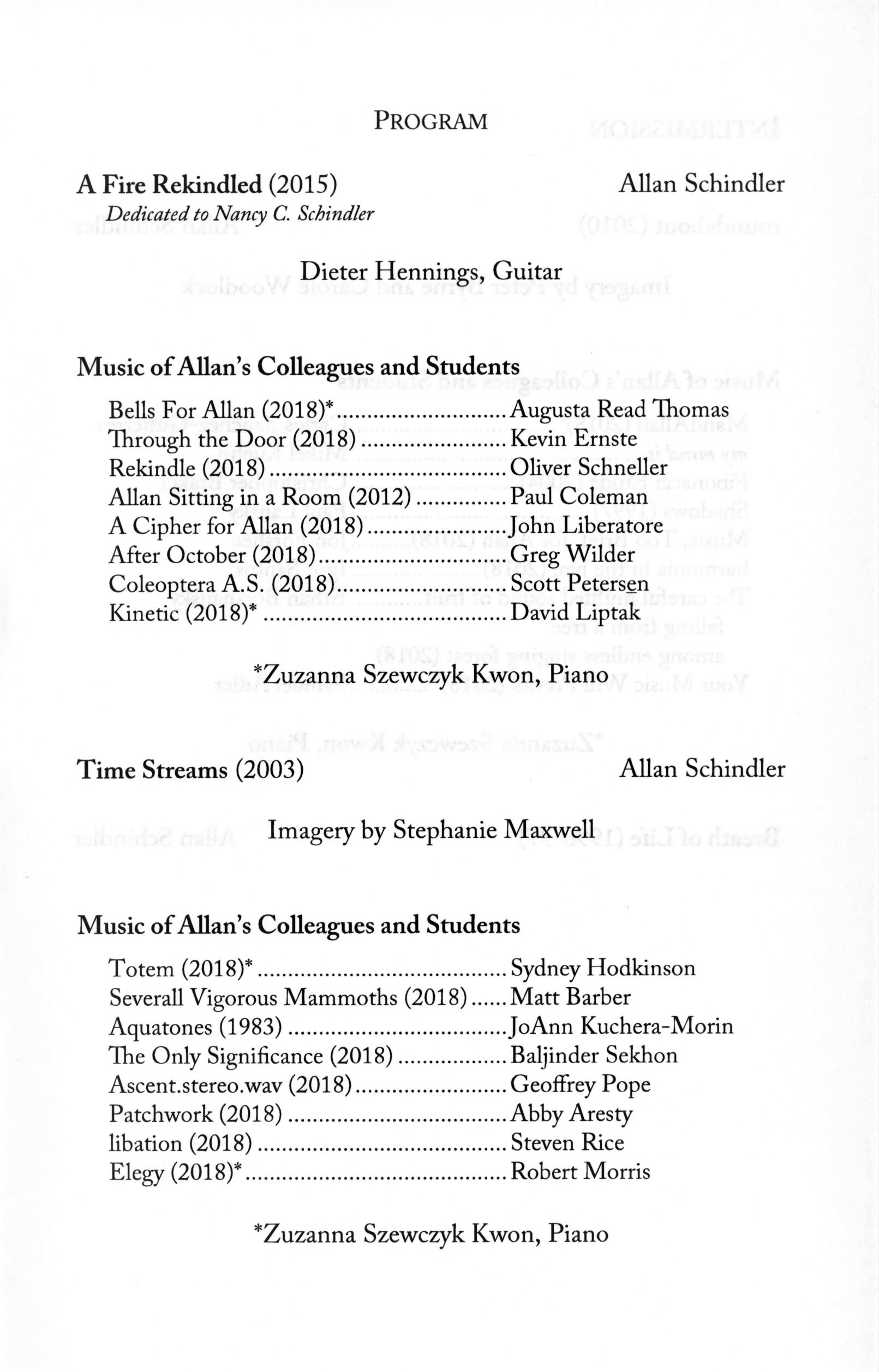

Schindler remained active as a composer after his 2015 retirement from Eastman, with his last completed work, a solo for classical guitar commissioned and premiered by Dieter Hennings at a pair of concerts by the Eastman BroadBand ensemble at Eastman’s Hatch Recital Hall and Ithaca College’s Ford Hall. Titled A Fire Rekindled (2015), the piece has, in the composer’s words, “a spontaneous, improvisatory, direct, and game-like quality” that makes the work “exhilarating” for performers and listeners, both. Like Schindler’s other works, A Fire Rekindled is constructed from “a collection of interlocking, mostly fragmentary and open-ended melodic, harmonic, rhythmic, and textural ideas” that, following his typical compositional approach to such “defining sounds,” Schindler combined thoughtfully in various orderings and juxtapositions with his typical deep musicality.[10]

After Schindler’s death in 2018, A Fire Rekindled was selected as the first piece in the memorial concert presented in the composer’s honor at Eastman’s Hatch Recital Hall, along with several other significant works from his oeuvre. Complementing these performances—and in tribute to Schindler’s immeasurable impact on the hundreds of composers and musicians who trained and studied with him and at the ECMC during his tenure as the center’s director—were two dozen works by Schindler’s colleagues and students. The program included works that had been completed while the composer was studying with Schindler, newly composed memorial tributes, and compositions that bore his influence in various, interesting ways. Given Schindler’s fierce advocacy for his students, his guidance toward developing a creative and mature autonomy, and his perpetual insistence on deep musicality, the musical homage was a beautiful testimony of Schindler’s lasting impact on Eastman, electroacoustic composition, and, more broadly, innovative art in all its diverse forms.

Endnotes

[1] Allan Schindler, “String Sextet,” Allan Schindler, composer [personal website], November 21, 2015.

[2] On his personal website, Schindler presented a curated works list of 21 compositions from his oeuvre. As explanation for the shortened list, he noted, “Over the years I have composed many other works, not listed here, several of which have had many more performances than some of the compositions listed below. The works included here, however, are those that I care about today.” Allan Schindler, “Currently Available Compositions,”Allan Schindler, composer [personal website], November 21, 2015.

[3] Allan Schindler, “String Sextet,” The page also includes a link to an audio excerpt of the Sextet’s conclusion from the OSSIA ensemble’s March 21, 2003, performance in Eastman’s Kilbourn Hall

[4] Allan Schindler, “Spring Winds, Autumn Gusts,” Allan Schindler, composer [personal website], November 21, 2015.

[5] Allan Schindler, “A (not so brief) History of the Eastman Computer Music Center,” in Eastman Computer Music Center: 25th Anniversary Concert Series (Rochester, NY: Eastman School of Music, 2007).

[6] Matt Barber, in “Allan Schindler Memorial Concert” program, November 7, 2018.

[7] A printout of the essay is also available in the Allan Schindler Collection, Box 19/14.

[8] Schindler and Maxwell wrote at length on this creative process in their co-authored chapter “Animated Image/Animated Music,” in The Sharpest Point: Animation at the End of Cinema, edited by Chris Gehman and Steve Reineke (Toronto: XYZ Books/Ottawa International Animation Festival/Images Festival, 2005): 198–205.

[9] Allan Schindler, “Second Sight,” Allan Schindler, composer [personal website], November 21, 2015.

[10] Allan Schindler, “A Fire Rekindled,” Allan Schindler, composer [personal website], November 21, 2015.

Audio Excerpts

Audio excerpts from 30 of Allan Schindler’s compositions are available on his personal website.

Recordings of Eternal Winter (1986), Take Me Places (1979), and Precipice (2004) are available via NAXOS.

External Links

Greg Wilder, “Allan Schindler Memorial” [memorial tribute with photographs from the Memorial Concert in Schindler’s honor and personal reflections from Wilder’s studied with Schindler], Greg Wilder [personal website], November 7, 2018.

For further information, please inquire at the Ruth T. Watanabe Special Collections department.