Online exhibit from the Ruth T. Watanabe Special Collections; curated by Gail E. Lowther.

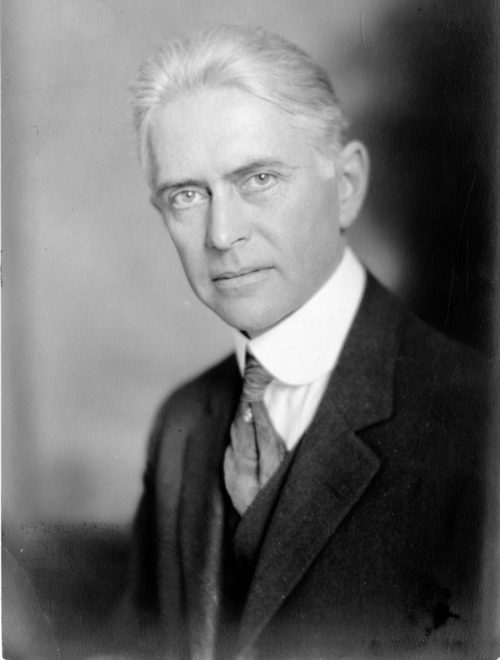

Today, the composer Arthur Farwell (1872–1952) is best remembered as a leading figure in the “Indianist” movement in American classical music (ca. 1890–1920). Certainly, Farwell held an important role as an advocate for Amerindian music in the early 20th century, given his ethnographic interest in Indigenous music and culture, his use of Amerindian music as source material in several of his own compositions, and his promotion of the genre via a series of cross-country lecture-recitals in the 1900s and his music publishing firm, the Wa-Wan Press. Yet, as several scholars have noted, Farwell’s “Indianist” works comprise only a small fraction of his oeuvre, and the remainder of his compositions and musical activities span an extraordinary and quite eclectic range of interests and influences, including turn-of-the-century Symbolism, American nationalism, community music-making, civic pageantry, harmonic experimentation, and Western Esoteric religious philosophies like Spiritualism, Theosophy, and New Thought. Traces of these diverse movements are evident throughout Farwell’s compositions and professional activities, with multiple influences often overlapping within specific works or projects.

This curated exhibit takes a look through the scores, photographs, and papers in the Arthur Farwell Collection at Sibley Music Library—the principal repository for Farwell’s manuscripts and papers[1]—with the aim of revealing these diverse influences and positioning them in the context of larger cultural movements to offer a kaleidoscopic view of turn-of-the-century American music making.

On Display

1

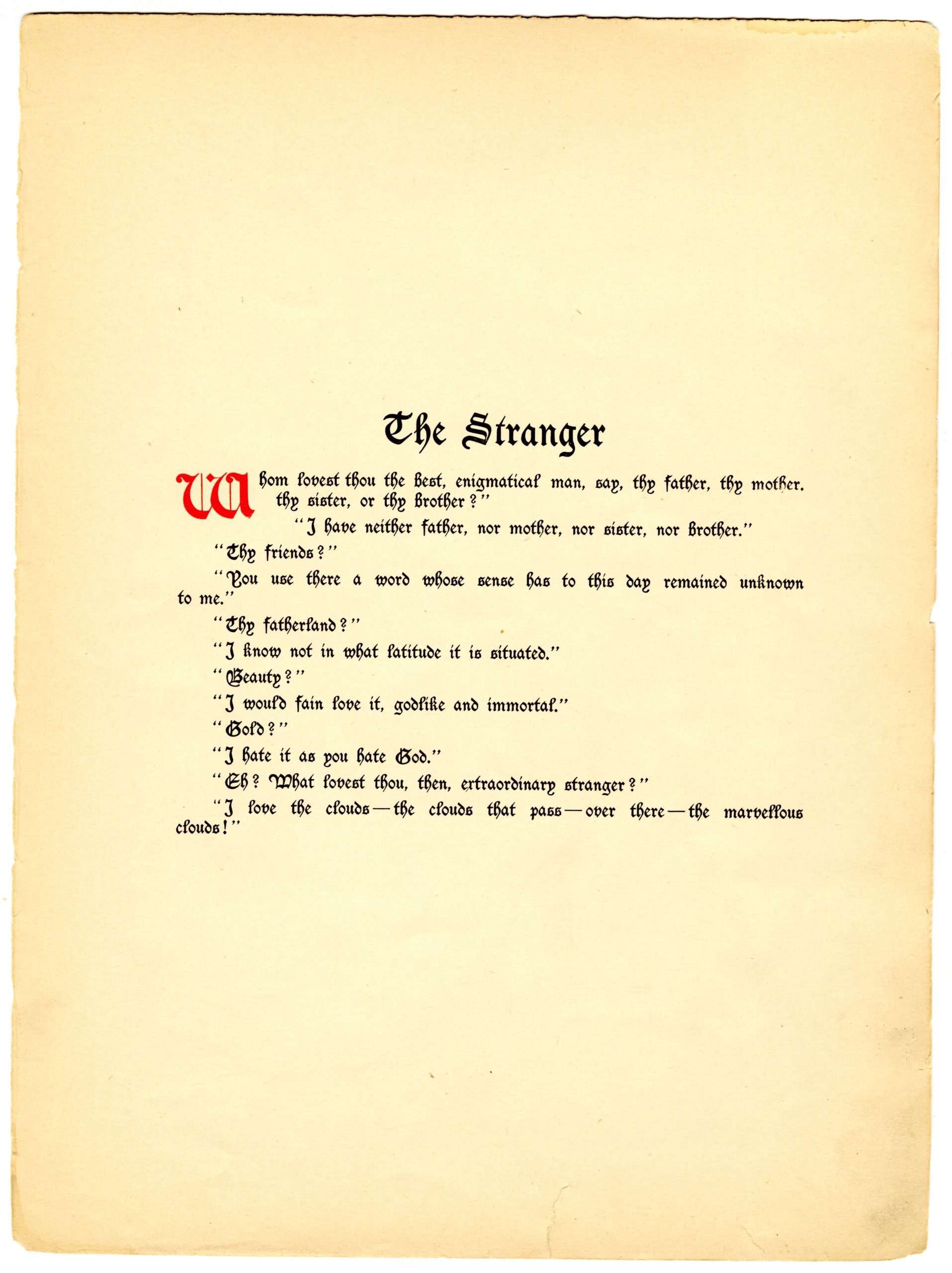

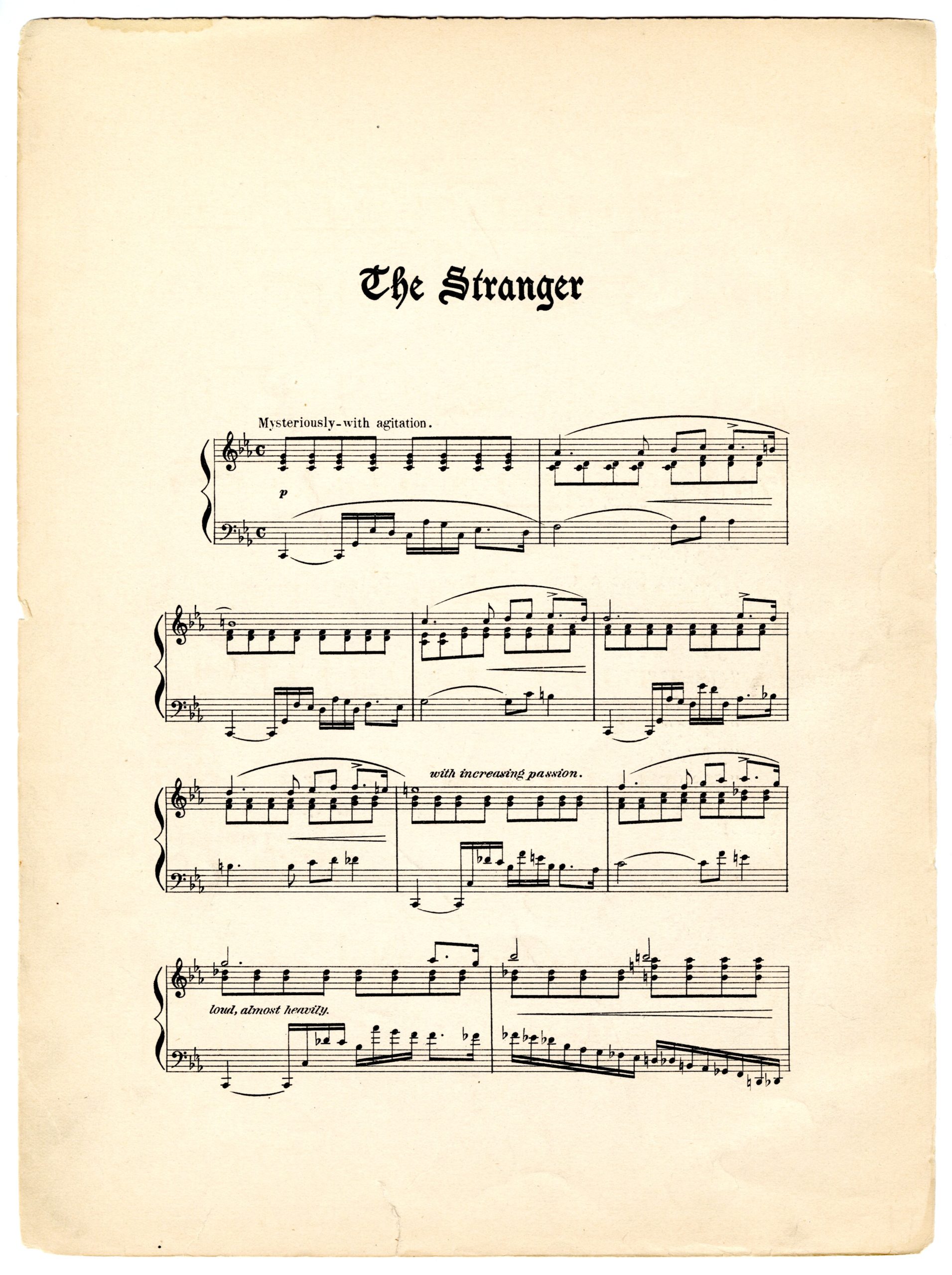

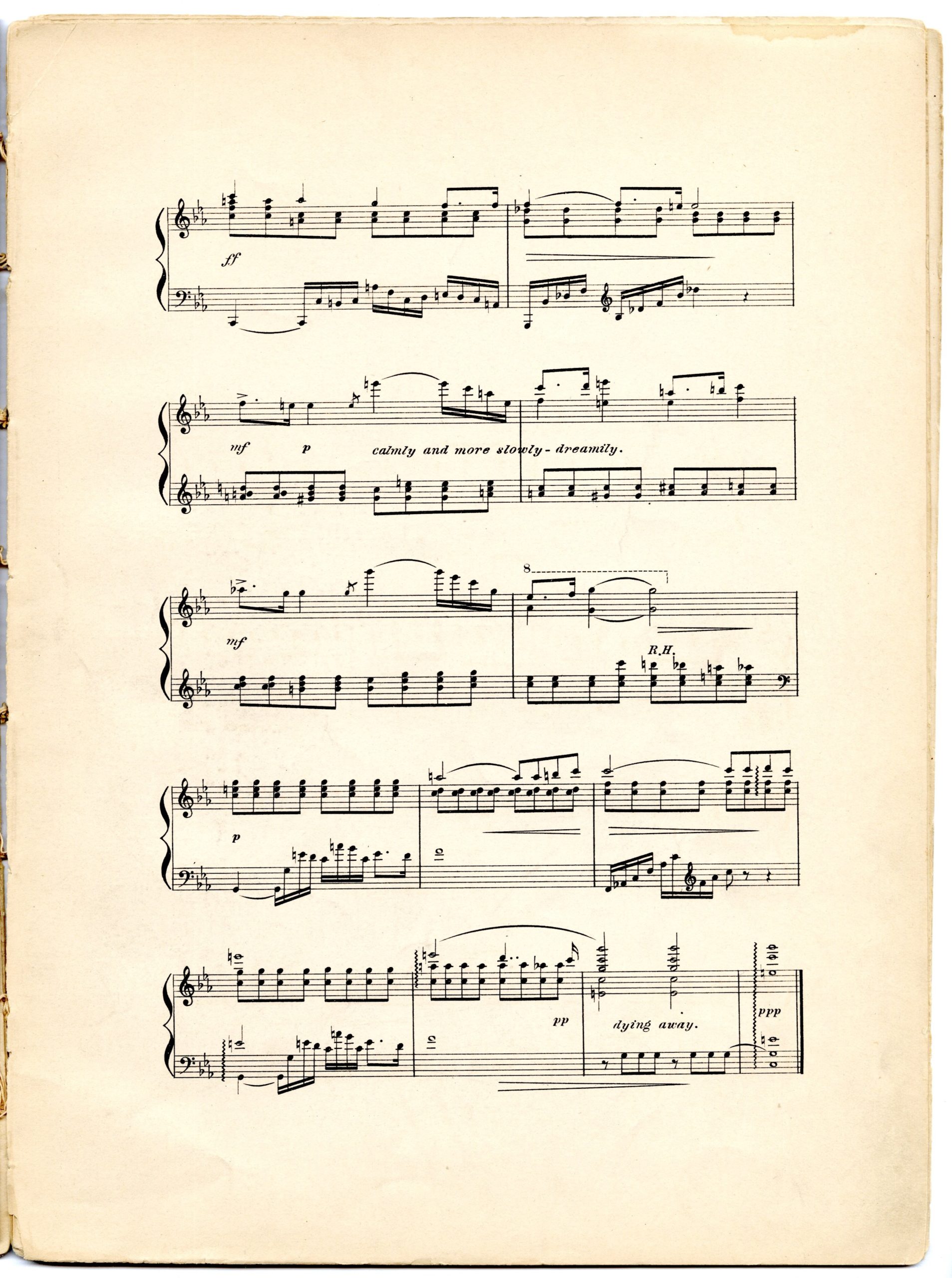

Arthur Farwell launched his professional career in music in 1899 after several years of serious study in Boston (1893–1897, with George Whitefield Chadwick and Homer Norris) and Europe (1897–1899, with Engelbert Humperdinck, Hans Pfitzner, and Alexandre Guilmant). His first published composition, Tone Pictures After Pastels in Prose, op. 7 (1895)—which he completed while studying composition with Chadwick—was a series of nine short pieces for solo piano, each inspired by and prefaced with a prose poem. After returning from his European training, Farwell continued exploring his interest in literature in a series of piano and orchestral compositions that he titled “Symbolistic Studies” in reference to the late 19th-century Symbolist movement. This aesthetic movement was initially conceived of and developed by a group of French poets as a reaction against a contemporary focus on artistic naturalism and realism. Instead of representing reality in their art, Symbolist poets like Charles Baudelaire, Stéphane Mallarmé, and Paul Verlaine sought to convey abstract truths, spiritual meaning, and inner emotions through symbolism, metaphor, and imagery. By the 1890s, the Symbolist aesthetic had spread beyond poetry and literature to influence painters, dramatists, and composers as well.

Given Farwell’s upbringing and penchant for the metaphysical, it is unsurprising that he was drawn to the Symbolist aesthetic. His mother, Sara Wyer Farwell, had studied astrology, Hinduism, Theosophy, and New Thought philosophies. As a child, Farwell learned to value visions, dreams, and other spiritual experiences; as an adult, Farwell regularly used techniques of meditation and visualization to access his inner, intuitive thoughts and creativity. The Symbolist aesthetic, in seeking to evoke the artist’s inner world, likely resonated with Farwell in his ongoing efforts to explore his own spiritual and artistic intuition.

2

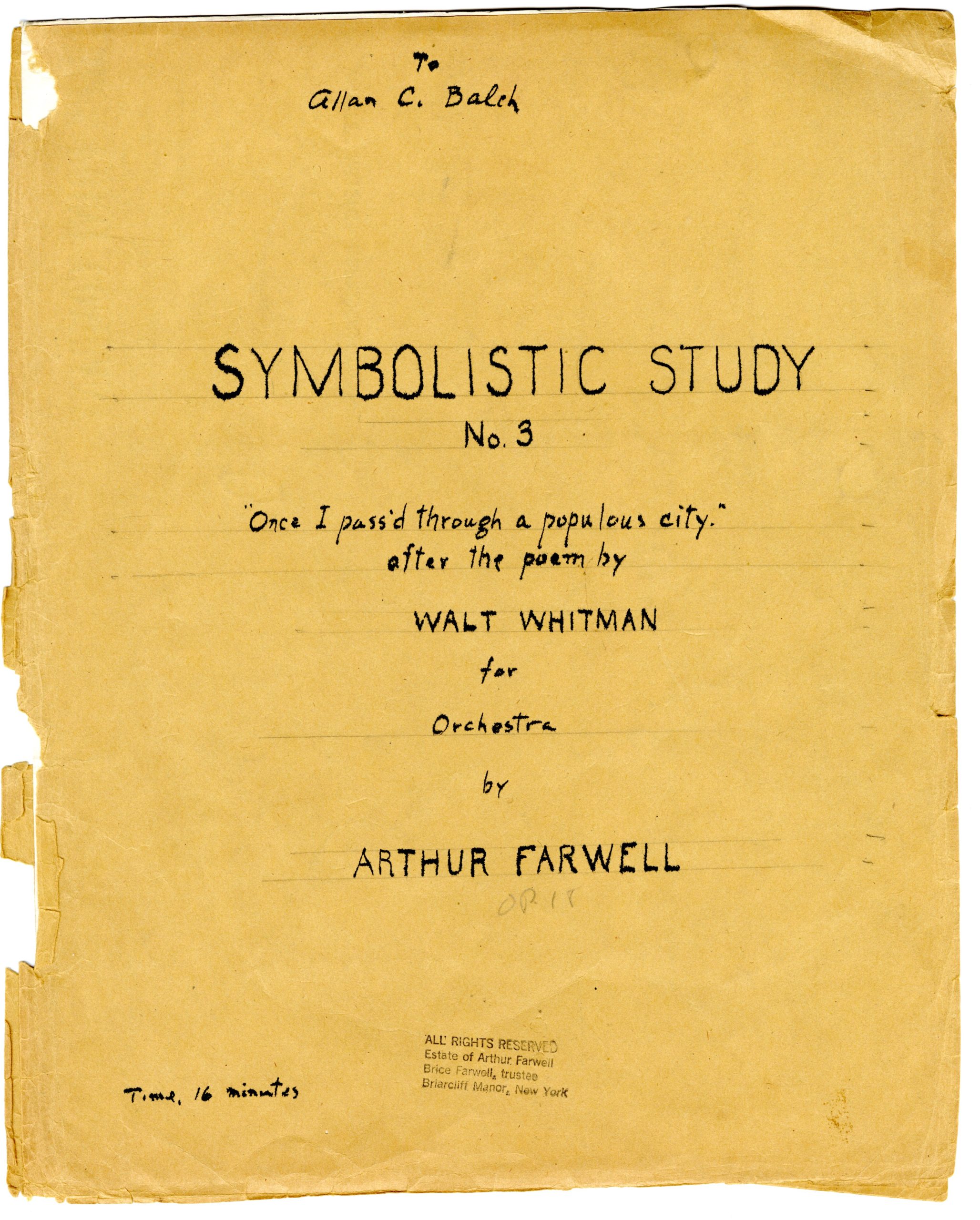

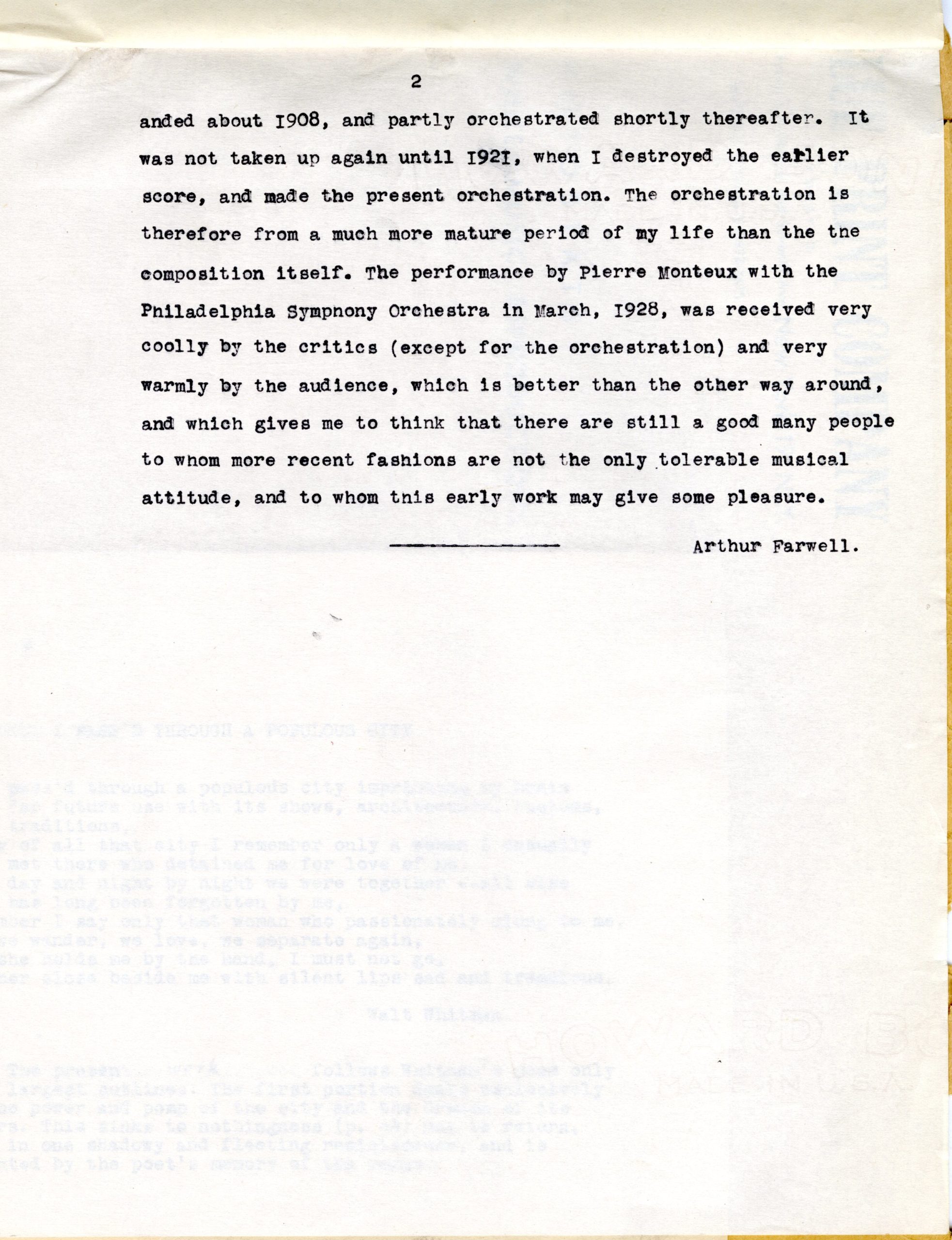

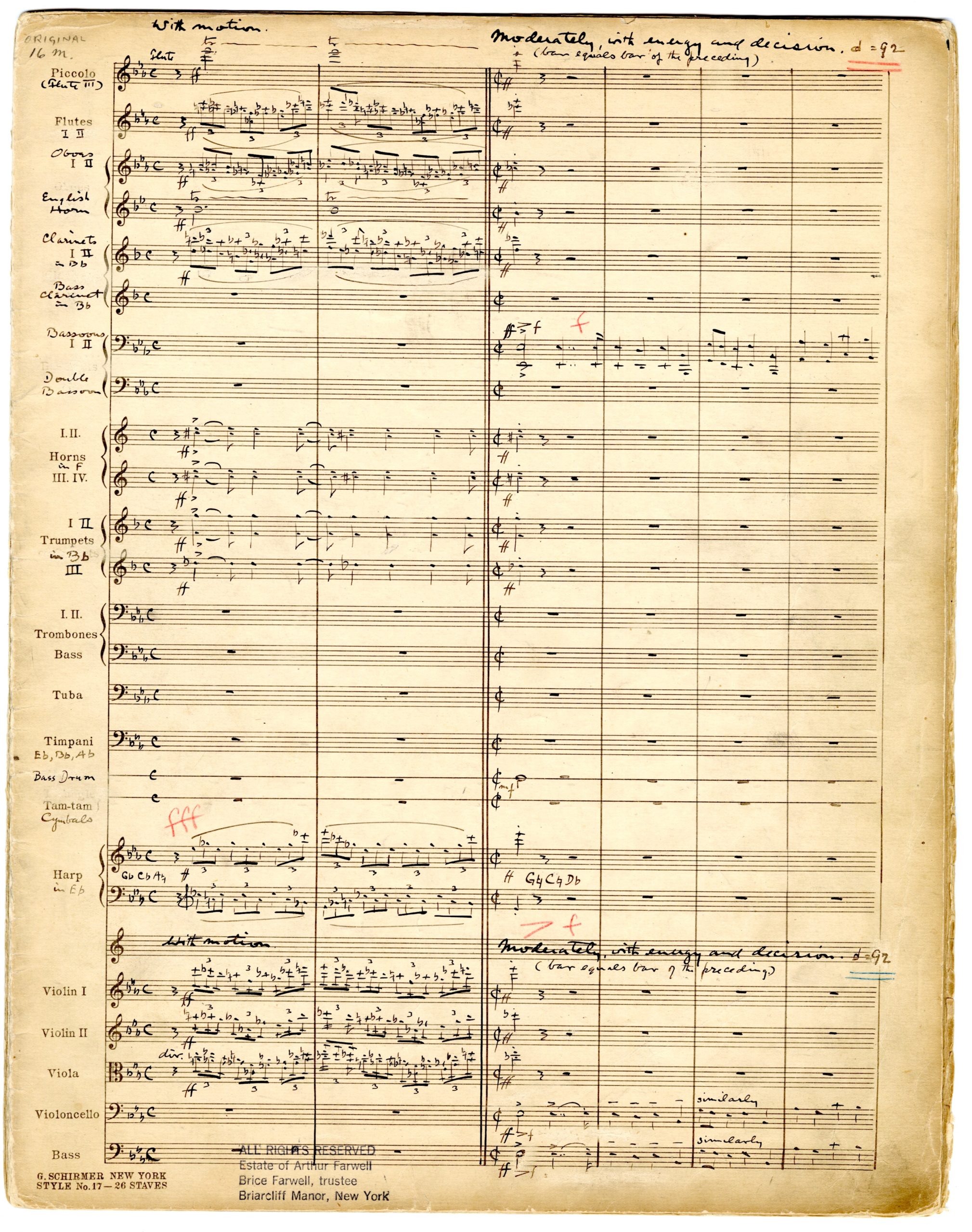

Between 1901 and 1912, Farwell began six “Symbolistic Studies,” but he completed only four. The first two—Symbolistic Study No. 1, Toward the Dream, op. 16 (1901), and Symbolistic Study No. 2, “Perhelion,” op. 17 (1904)—were for solo piano, though unfinished sketches indicate that he began reworking the second solo for orchestra. The third study, subtitled “Once I Passed Through a Populous City” after Walt Whitman’s eponymous poem, is for orchestra (1908, re-orchestrated 1921). As Farwell explained, in his series of symbolistic studies, he aimed to “use the obvious symbolic power of music” to express the ideas and themes of his source material without an explicit musical program.[2] He further elaborated on his approach in the composer’s notes for Symbolistic Study No. 3:

The term “Symbolistic Study” was employed by me for a series of works begun in 1901, when the symbolistic movement in literature was at its height. In these works I was using music frankly as a symbol of specific ideas, but avoiding all close following of a program and letting the music rest on thematic presentation and development. The Whitman poem presents two sharply contrasted pictures, one on the material plane—the imposing city—and one on the psychic—the memory of an emotional experience. To this extent, being in fact two compositions, separated in time by a mere instant’s pause, but in level by the distance between the material and the psychic. The second part however contains a momentary and shadowy memory of the city, as something remote and unreal from the standpoint of the emotional experience.

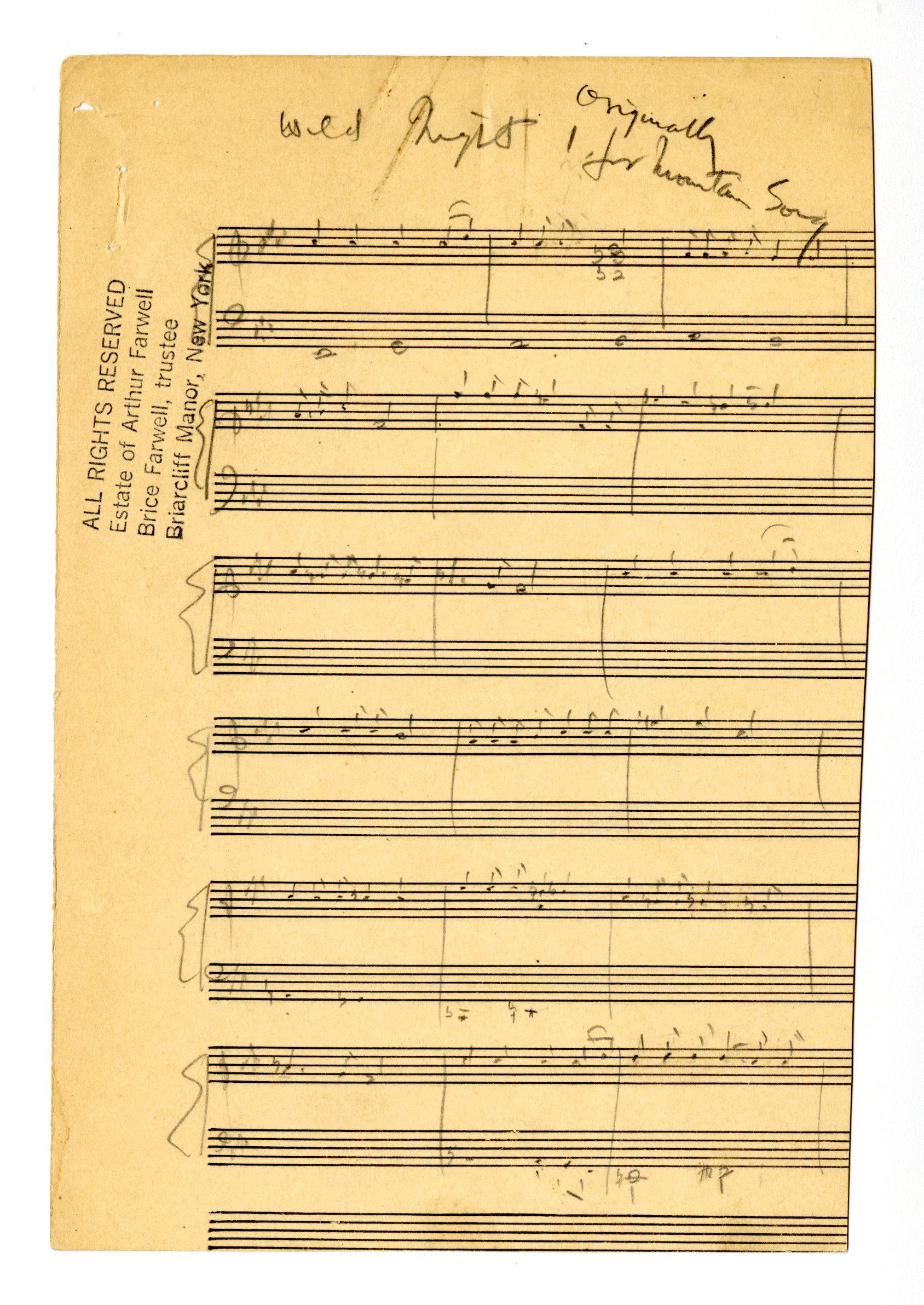

Farwell began sketches for a fourth and fifth study, for solo piano and orchestra, respectively, but those works were not completed. His last effort in this project was Symbolistic Study No. 6, Mountain Vision, op. 37, which was written initially for solo piano (1912) and then reworked for two pianos and string orchestra (1931). Unlike Farwell’s earlier symbolistic studies, this piece was not based on a pre-existing literary work; rather, Farwell applied a similar symbolic approach to evoke a psychological program of struggle inspired by mountain scenery. In several later works, such as his piano suite In the Tetons (1930) and the five-movement “symphonic song ceremony” Mountain Song (1931), Farwell also turned to nature for inspiration, attempting to capture its beauty and grandeur through musical “nature-painting.”[3]

3

It was during this same period—the 1900s and 1910s—that Farwell produced the bulk of his “Indianist” music, that is, pieces of Western art music that were based on Amerindian melodies. In this effort, Farwell was joined by several other American composers, including Charles Wakefield Cadman (1881–1946), John Comfort Fillmore (1843–1898), Henry F. Gilbert (1868–1928), and Amy Beach (1867–1944), who similarly looked to Amerindian music as source material for a new nationalistic style of American art music. From about 1890 to the 1920s, these composers incorporated “Indian” elements—from narratives and myths to isolated rhythmic features to whole melodies—into new compositions that otherwise relied on the structure and form of traditional Western art music. This impulse to look to ethnic folk music as source material mirrored nationalistic movements that emerged across Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. However, as Tara Browner has observed, compared to European nationalist composers, who predominately used music from their own cultural heritage, the Indianists were unique in coopting Indigenous music as “nationalist by geography”; none of the participating composers claimed Amerindian heritage but rather saw Native musics as a representative and ethnically unique stand-in for “American” culture and its citizens’ mixed ethnic origins.[4] Moreover, most of these composers encountered the source material second-hand through published, Westernized transcriptions by ethnologists like Alice Fletcher and Francis LaFlesche.

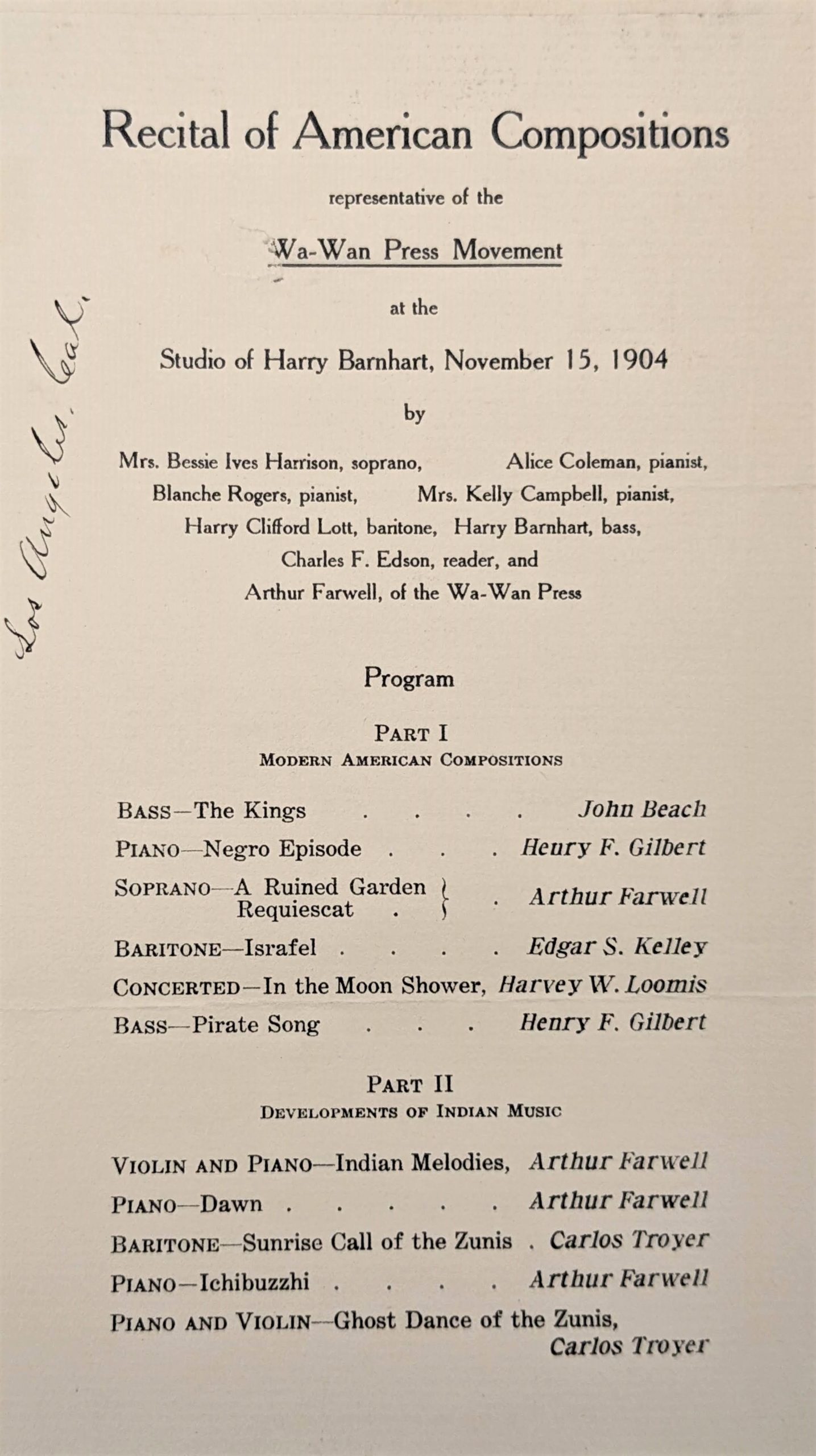

Farwell was among the most ardent advocates for Amerindian music and its incorporation into American art music. He believed it could revitalize the American musical aesthetic and establish a distinct musical style that would stand out from the music of European composers. In 1901, he founded a music publishing firm—the Wa-Wan Press—which was specifically devoted to publishing serious compositions by American composers, including “worthwhile work done with American folk material as a basis.”[5] Farwell articulated this vision in over a dozen essays for professional journals, popular magazines, and his newsletter The Wa-Wan Press Monthly. He further complemented his writings with a series of transcontinental lecture-recitals on “Music and Myth of the American Indians, and Its Relation to American Composers” (1903–1904) and “A National American Music” (1906–1907). In a 1904 article for Out West Magazine, Farwell explained his aims thus:

The Indian music is now promising to be one of the most important factors [in American music]. This is due to its intrinsic force and beauty, and to the intimacy of the Indian’s relation to the history of all parts of these states, as well as to the powerful and suggestive mythology supporting it. In the still largely unrevealed subjective life of the Indian the ethnologist has found another world, rich in poetry, mystery, elemental philosophy, mythic lore, close to our own, yet generally unperceived by us in its true fullness and significance. Science has discovered this world: but the opportunity—the privilege—the need—of its ideal representation in terms comprehensible to all, falls to art. And since the Indian has entrusted so large a share of his own expression of his life and thought to music, the unearthing of this music and bringing it into the open of our musical life is one of the greatest and most obvious musical tasks before America at the present moment.[6]

4

In the early 1900s, Farwell took up his own call to incorporate Amerindian music, beginning with a set of American Indian Melodies, op. 11 (1900), for solo piano. For this collection, he selected ten melodies from Alice C. Fletcher’s Indian Story and Song from North America (with songs harmonized by John Comfort Fillmore) and presented the tunes with little deviation from Fletcher’s transcriptions.

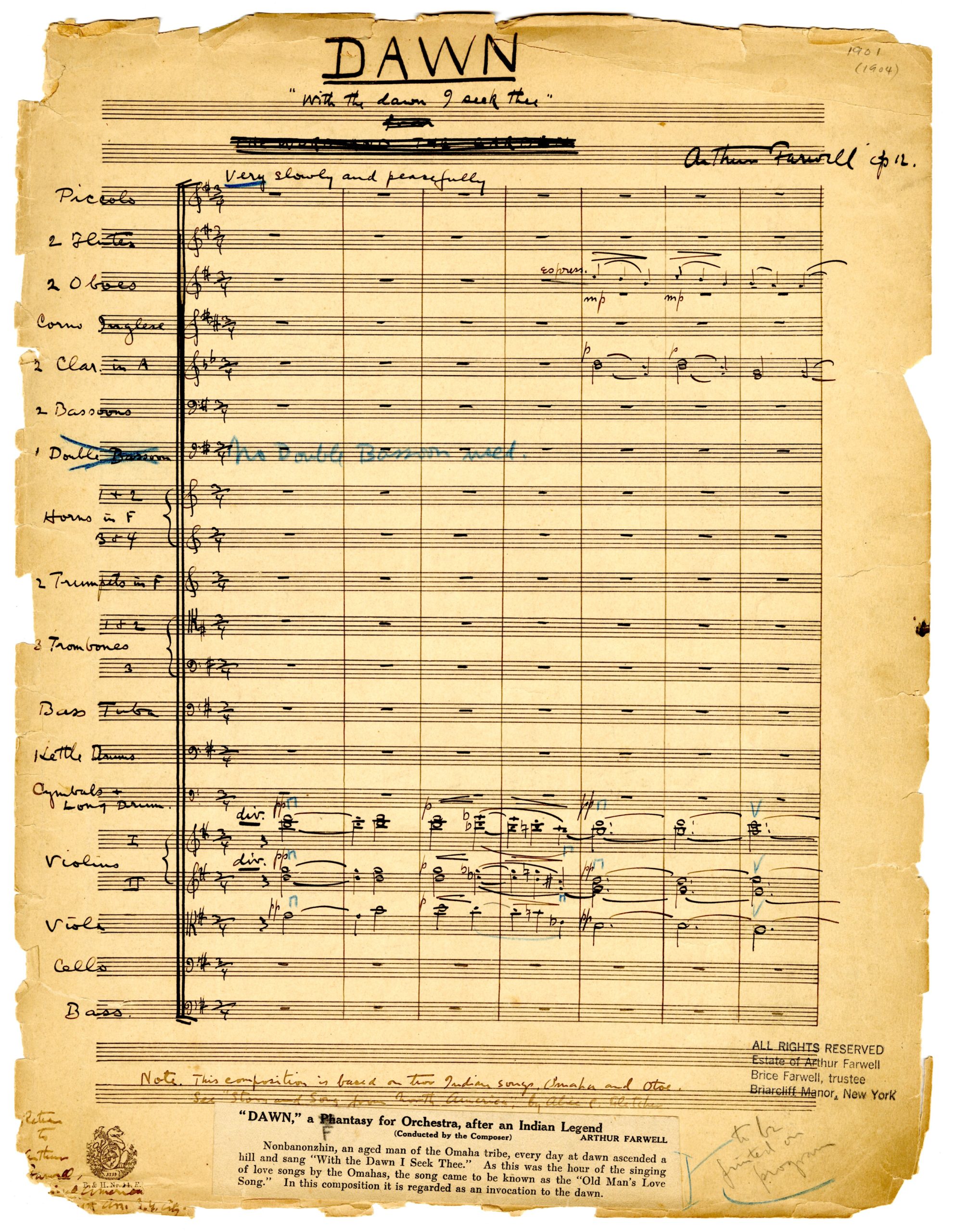

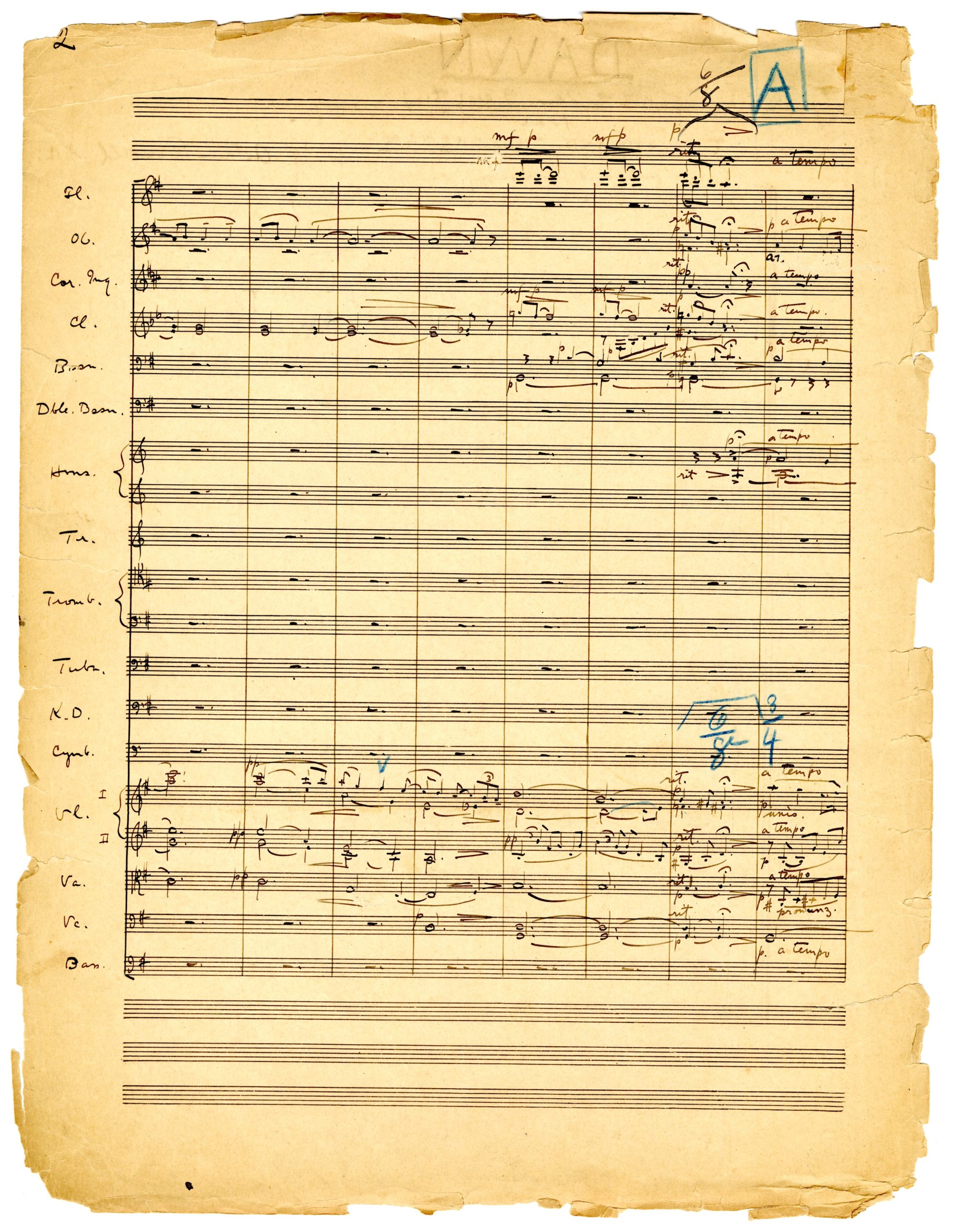

Farwell appears to have been particularly taken with the melody he used in the second piece in the series: an Omaha song, published in Fletcher’s anthology as “The Old Man’s Love Song.” Farwell returned to this song again and again in his Indianist compositions. Beth Levy has noted how Farwell consistently preserved the melody in his settings—from the original version for solo piano (1900) to later works for solo voice (1908) and a cappella chorus (1901, 1937)—suggesting a “reverence for the source text.”[7] However, in all of his arrangements, Farwell rejected Fillmore’s simplistic, functional harmonization in favor of chromatic, Wagnerian-inspired harmonies. The tune also appears in an extended version in the piano solo Dawn, op. 12 (and the companion orchestral version), in which the Farwell alternates the Omaha melody with a simple Otoe song in a loose ABA’B’ structure.

By 1912, Farwell had largely moved on from Indianist music in favor of other projects. In the 1920s and 1930s, he produced only a few Indianist-inspired compositions, and most of those were revisions of earlier compositions. (The most notable exception to this is the Hako String Quartet, op. 65, a musical interpretation of the Pawnee Hako ceremony in sonata form, which Farwell completed in 1922.) Instead, Farwell’s interests turned increasingly to other forms of American folk music for inspiration, including cowboy songs, spirituals, and—after Farwell moved West in 1918—“Spanish Californian” songs. Although his source for this folk material had changed, he remained faithful to the same impetus that had originally spurred his interest in Amerindian music, that is, to create a national style of music that would reflect American life and character.

5

During his “Indianist” period (ca. 1900–1912), Farwell also wrote and lectured extensively about his concerns for contemporary American music and his hope for establishing a uniquely American style of art music. Further, his interest in the future of American music drove him to seek out ways to support American composers by publishing and performing their music. The Wa-Wan Press, in publishing music by American composers, fulfilled one of those aims. To promote the study and performance of these new American compositions, Farwell turned to music clubs. In April 1905, he founded the American Music Society in Boston, a local music club with monthly meetings at which members would discuss, study, and perform music by American composers. In 1907, building on his previous work in Boston and with the Wa-Wan Press, Farwell founded the National Wa-Wan Society, which he described as “a national organization for the advancement of the work of American composers, and the interests of the musical life of the American people.”[8] Six “Centers” for the Society were established in cities across the United States, from Rochester, NY, to San Diego, CA. The next year, in 1908, Farwell combined the two groups as a national American Music Society, with centers in at least 12 cities, including New York City. Although Farwell’s American Music Society appears to have been short-lived—his biographer, Evelyn Davis Culbertson, only traces activity through 1911[9]—the organizational structure Farwell established in the Society’s centers served as a model for new music clubs and organizations in the 1920s and beyond.

6

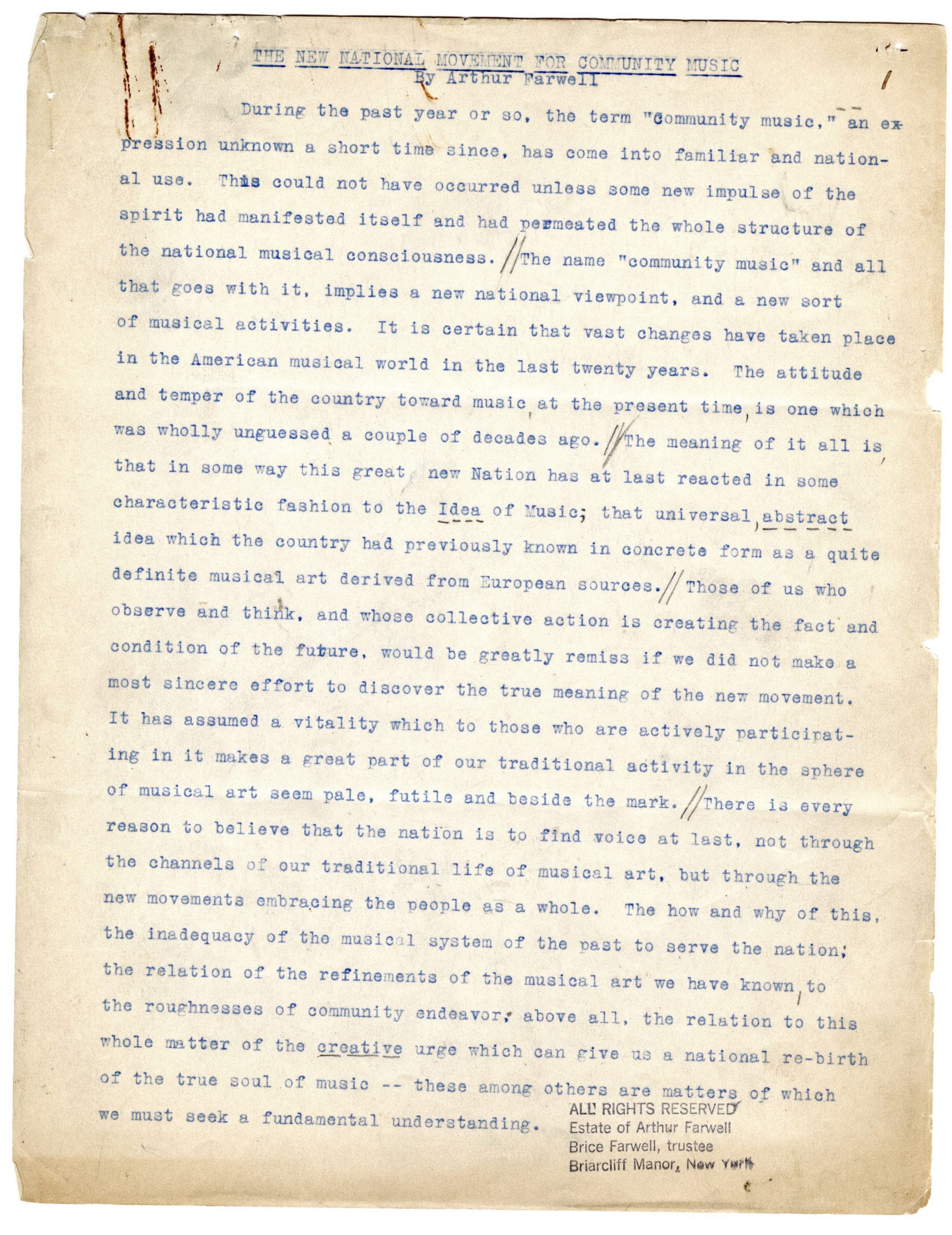

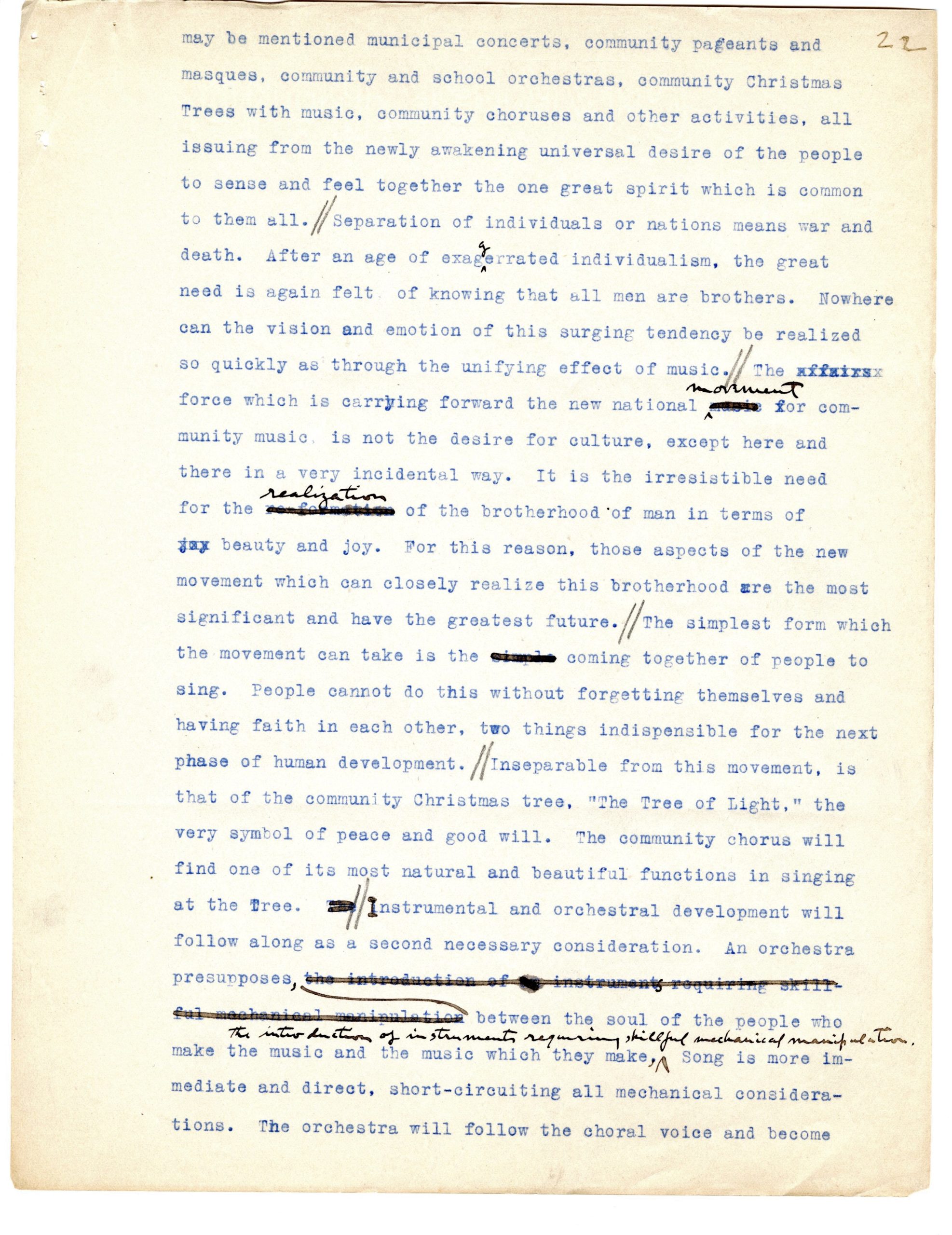

Over the next two decades—from about 1908 to the 1930s—Farwell’s concern for American musical life and social reform drove him into a new realm: that of community music making. In this, he joined a group of other music educators, composer/musicians, and community activists who promoted a philosophy of “social improvement through art” via public concerts, amateur music-making, and community music education. These community music activists were motivated in part by a larger aim to rebuild the sense of community and social cohesion that they felt had been lost in modern life due to urbanization and the Industrial Revolution. In many ways, the movement’s ideals mirrored and built off those of the contemporaneous Arts and Crafts movement and the Settlement House Movement, which similarly sought to achieve Progressive social reform through art. Across the United States, community music activists like Peter Dykema (1873–1951) and Edgar B. Gordon (1875–1961), both early presidents of the Music Supervisors’ National Conference (now National Association for Music Education, or NAfME), promoted group music making by founding amateur singing groups, publishing song books and instruction manuals, organizing community “sings,” and expounding the social benefits of community music making in articles and lectures.

Beginning around 1908, Farwell, still a prolific writer, gradually turned his focus away from Amerindian music and musical nationalism to promote and develop his views on community music. After becoming chief music critic for Musical America in 1909, Farwell used his weekly essays and reviews in the newspaper to bring national attention to community music projects in New York City and elsewhere, including many of his own. From 1910–1913, Farwell served as Supervisor of Municipal Concerts in New York City, where he organized summer concerts in the city’s parks and recreational piers, and from 1915–1918, he served as director of the Third Street Music School Settlement (founded 1894). These roles gave Farwell ample opportunities to experiment with community music projects and refine his philosophy, which he termed the “New Gospel of Music.” In a two-part article for Musical America, Farwell summarized this “Gospel” thus:

“That the message of music at its greatest and highest is not for the few, but for all; not sometime, but now; that it is to be given to all, and can be received by all.”[10]

7

During this same period, the country was experiencing what has since been described as a “pageantry craze”[11]—another community-focused artistic movement that was fueled by several of the same Progressive impulses and ideals that inspired the Community Music Movement. Between 1905 and 1935, hundreds of towns across the United States mounted large historical pageants as part of local civic celebrations and community entertainments. These presentations were an outgrowth of 19th-century dramatic forms like the tableaux vivant, combined with a Progressive Era focus on civic regeneration. In pageants, performers reenacted a series of important episodes from local history in static tableaux or dramatic scenes with dialogue, which they embellished with oratory, patriotic songs and choruses, musical interludes, and dances. As the genre evolved through the 1910s, pageants increasingly incorporated social and political agendas through spectacle and allegory, from women’s suffrage to labor reform and wartime mobilization during World War I. By 1913, an official American Pageant Association (APA) had been formed with an eye toward codifying a unifying philosophy for pageant organizers and formulating concrete guidelines for the emerging genre.

Farwell joined the pageant movement almost on the ground floor. He was known by several leading pageant organizers, including the APA’s first president William Chauncy Langdon (1831–1895), through his lectures to the Twentieth Century Club of Boston, and he collaborated with others involved in the movement in his role as Supervisor of Municipal Concerts for New York City (1910–1913). Thanks to these associations, his extensive musical network, and his well-publicized interest in community music, Farwell was invited to become a charter member of the APA’s Board of Directors, and he joined the organization’s initial advisory committee of specialists as a musical advisor. Farwell also composed and conducted music for several pageants, including Langdon’s historical pageants for the towns of Meriden, New Hampshire (June 1913), and Darien, Connecticut (August 1913), as well as Percy MacKay’s masque Caliban by the Yellow Sands in St. Louis, which celebrated the Tercentenary of Shakespeare’s death (May 1916).

Farwell also promoted pageantry in articles and lectures to professional associations in which he articulated the movement’s aims and offered advice to pageant composers and organizers. In an article for the APA’s Bulletin, Farwell summarized his idealistic vision, which was grounded in his artistic philosophy of social reform:

We are to look at pageant music not as an off-shoot from the world of music in general, but as something more vital and creative than most of that which arises otherwise. For it marks a departure from the artificialities and decadent importations which constitute much the greater part of the affairs of our musical world, and fills a distinct need of the people for something which is appropriate and belongs to them.[12]

8

A key component of Farwell’s community music philosophy was a theory of communal aesthetic experience that he termed “mass appreciation.” In his 1914 article on “The New Gospel of Music,” Farwell defined this as “the spontaneous response of the human mass to the substantive reality in all music, however great, without previous education in musical appreciation.” In other words, Farwell proposed that music—and community music making in particular—could inspire a deep aesthetic response in even untrained audiences: one did not need to understand the music intellectually or analytically to gain the “full measure of spiritual nourishment” from the aesthetic experience. According to Farwell, audiences so affected by “mass appreciation” would be overcome with a “spontaneous and glowing sense of joy, universally felt” as “a reaction to sheer beauty.”[13]

In his pageants, Farwell sought to inspire “mass appreciation” through musical drama and spectacle. In New York in 1915–1918, he approached it through another, radical experiment: a public festival that would link community song with elaborate ornamental lighting for maximum effect.

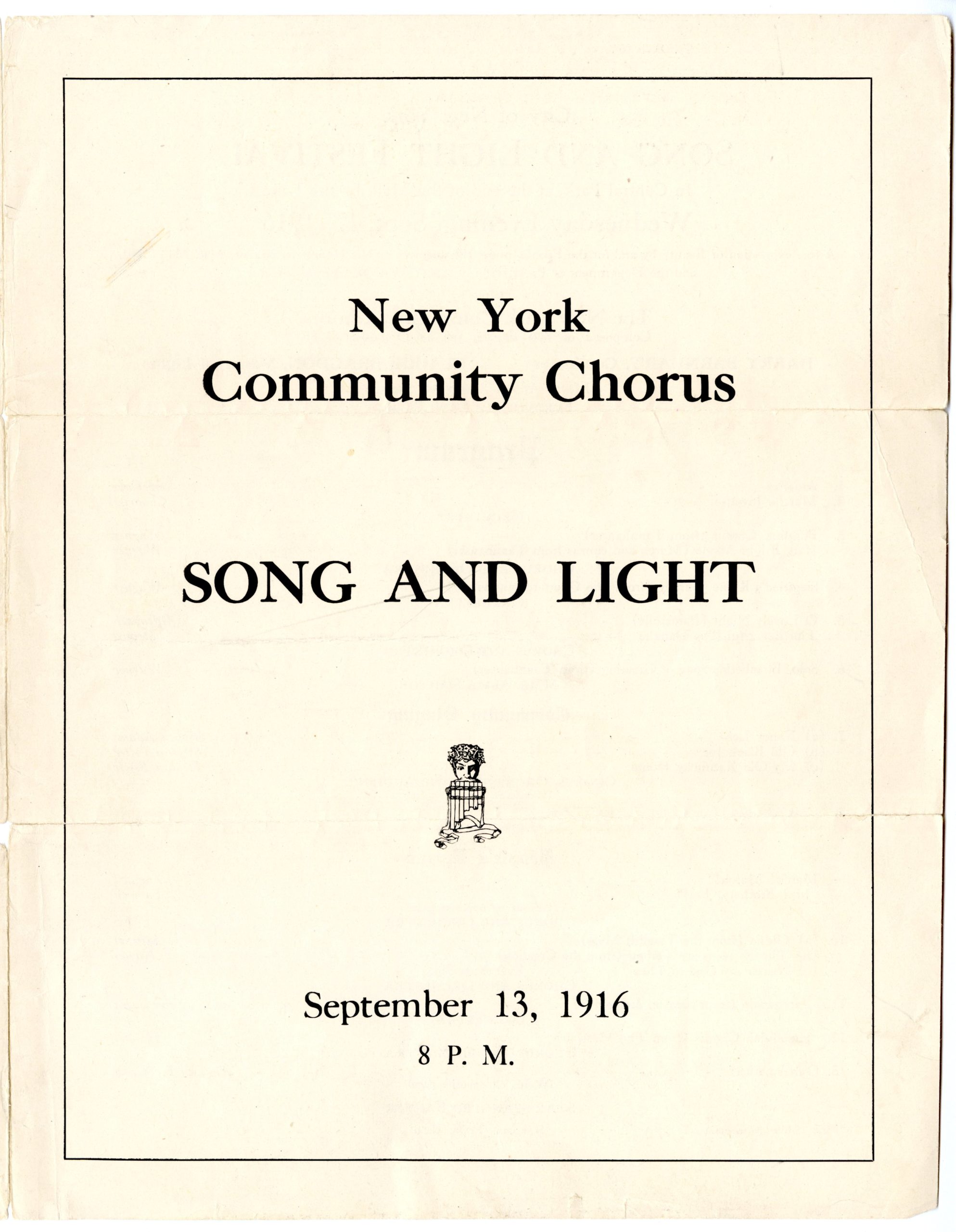

The resulting Song and Light Festival was the brainchild of three visionaries: Arthur Farwell, the community music organizer Harry H. Barnhart (1874–1948), and the modernist architect and designer Claude Bragdon (1866–1946). Farwell had met Harry Barnhart—a classically trained baritone and choral director—in Los Angeles in 1904 during a stop on one of the composer’s lecture-recital circuits. By 1909, Barnhart had relocated to New York, where, beginning in 1914, he founded a series of Community Choruses in Rochester, Buffalo, Syracuse, New York City, and New Jersey that were based on his and Farwell’s principles for community music making.[14] In September 1915, to close the Rochester Community Chorus’s first season, Barnhart organized an ambitious song festival in Rochester’s Highland Park, with intricate lighting designs provided by his friend, Claude Bragdon. The effect was electrifying.

The team mounted several subsequent Song and Light events between 1915 and 1918, including a massive festival in Central Park with the New York Community Chorus, a 65-member orchestra, and two newly composed patriotic songs by Farwell that incorporated audience participation (“March! March!” and “Joy! Brothers, Joy!”).

Bragdon’s ornamental lighting for these events was spectacular. He designed an elaborate set of light screens, decorative lanterns, and proscenium lights based on a complex synthesis of formal, mathematic, and symbolic principles. In his designs, Bragdon combined the theory of Pure Design with Western and Eastern architectural principles, natural harmonics, Theosophical doctrines (including four-dimensional geometry), and a symbolic color scheme that linked each individual color to a specific musical pitch for a synesthesia-like effect.[15] Bragdon’s aim was to create a “cathedral without walls” that would have a deep psychological effect on the festival-goers that would be reminiscent of a religious or mystical trance, effectively heightening the experience of “mass appreciation.”

With the United States’ entry into World War I in 1917, the Song and Light Festivals took on more a patriotic and somewhat militaristic tone. Between August 1917 and September 1918, Farwell, Barnhart, and Bragdon staged three final Festivals—one at the New York State Fairgrounds in Syracuse and the last two in the City with the New York Community Chorus—in collaboration with US Army administrators. Military bands performed alongside the community choruses, and the procession of soldiers and sailors gave the public opportunity to celebrate and bid farewell to local recruits leaving for training or deployment. Soon after, the Community Music Movement was coopted by military leaders to forge community among the armed forces, and Barnhart and Farwell, along with dozens of other community music organizers, were recruited to organize group singing in Army and Navy training camps.

9

In the summer of 1918, Farwell and his family moved to California after the composer accepted a position at the University of California, initially to serve as a lecturer at UCLA’s summer session (1918) and then as Associate Professor of Music and acting head of the music department at UC Berkley (1918–1919). After his contract at UC Berkeley ended, the Farwells moved to Santa Barbara, where the composer busied himself with community music projects: he organized community choruses in Santa Barbara and Pasadena, composed and arranged music for the ensembles, prepared the original pageants La Primavera (1920) and The Pilgrimage Play (1921), and lectured on community music-drama and music-making. In these efforts, Farwell returned again and again to folk music, though now he favored cowboy tunes and Hispanic folk songs rather than Amerindian melodies. His arrangements of “Spanish California” songs for the Santa Barbara Community Chorus were audience favorites, and in 1923, he prepared fourteen of these arrangements for publication in the collection Spanish Songs of Old California.

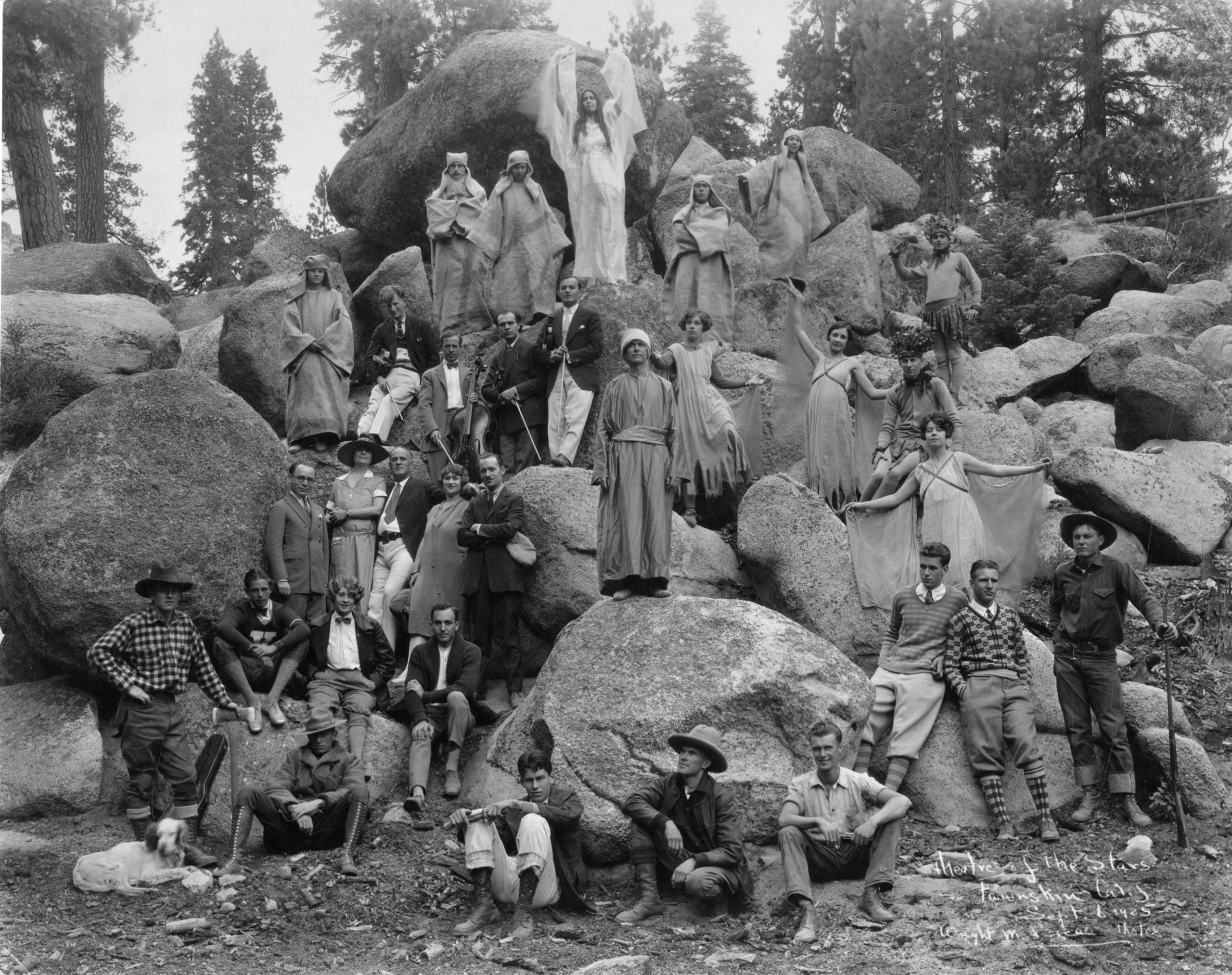

In 1924–1925, Farwell’s interest in community music reached a peak, both literally and figuratively, as artistic director for the short-lived “Theater of the Stars,” an outdoor theater at Fawnskin, CA, a resort community in the San Bernardino Mountains. In building the theater, Farwell and the other developers took advantage of the large canyon’s natural amphitheater and picturesque forest background. The main stage was set on the floor of the canyon, and additional performance areas were scattered across the surrounding forest, extending up nearly 450 feet to the canyon rim. The stirring effect of the theater’s natural setting was further enhanced with dramatic, multicolored theatrical lighting. As one reviewer described: “The theatre is set among boulders and lofty evergreens in a canyon upon the heights of a mountain range. It is lighted below by camp fires and above not only by the stars but by lights of various hues, the colors changing in keeping with the moods of the music.”[16]

Though Farwell was involved only for one season—his plans for the 1926 were cancelled when the theater’s funding was pulled—he mounted an ambitious schedule of performances for 1925 that closed with Farwell’s own The March of Man (1925), an allegorical masque that decried violence against nature and the destruction of the environment. Although little music from the production survives, the libretto and production material (including 12 photographs of the performance) are preserved in the Arthur Farwell Collection.

As the composer’s biographer, Evelyn Culbertson Davis, summarized, Farwell’s community music projects—and particularly his work in pageantry—were in many ways a “culmination of all Farwell had striven for in his crusade for American music. This was a vehicle for the people, of the people, and by the people. It was Democracy in action!”[17]

10

In 1927, Farwell was recruited to help establish a new Institute of Music and Allied Arts at Michigan State College of Agriculture and Applied Science (now Michigan State University) as the head of the music theory and composition division. After spending decades of cobbling together a livelihood from various freelance and short-lived projects, often with tenuous financial outlooks, he was attracted by the financial stability a faculty position offered. Yet Farwell soon found that the professorship, with what he described as a burdensome teaching load, was a poor fit for him.[18] He even attempted to resign in 1932, but the administration would not accept his resignation. Ultimately, he stayed at Michigan State until 1939, when a new policy at the college forced his retirement at the age of 67.

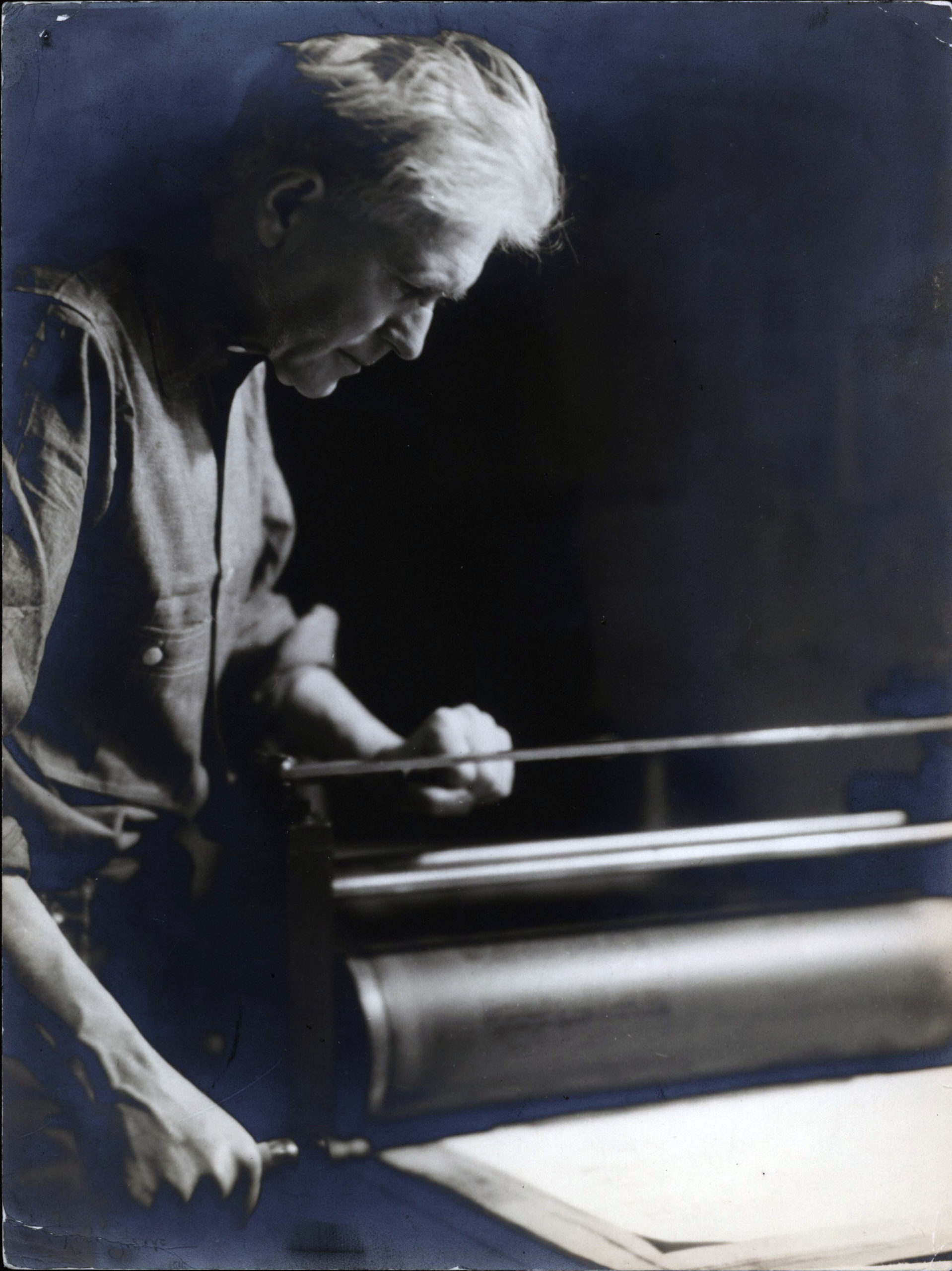

Farwell spent his last years in New York City, where he divided his time between his family—his second wife gave birth to his last (seventh) child in 1941—and ongoing professional activities: composing, self-publishing his music (on his own lithograph press), some ASCAP committee work, and writing a monograph on his artistic process and philosophy.

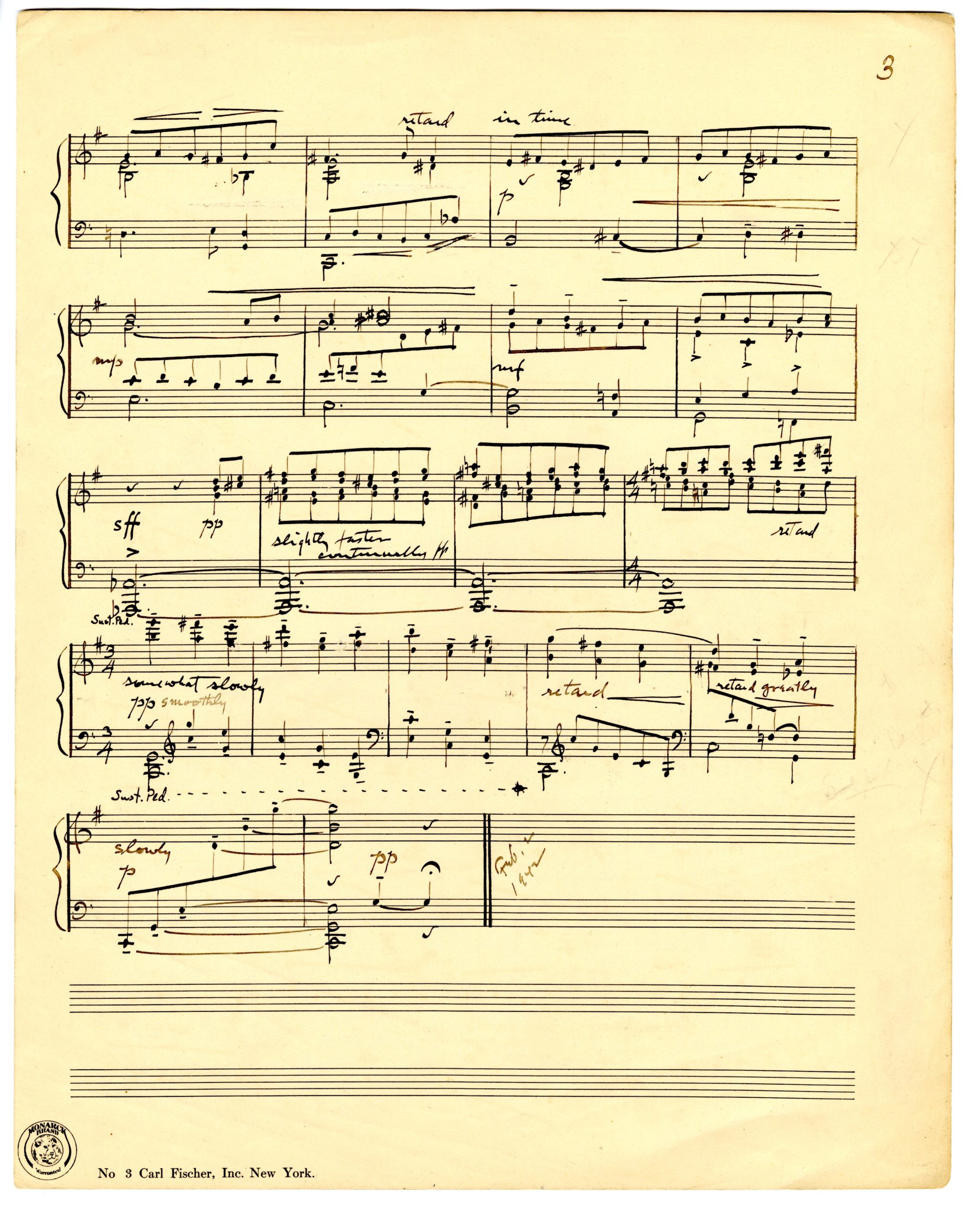

Although Farwell described himself as a Romantic composer, several of his late works feature harmonic experimentation that pushes against the boundaries of 19th-century functional tonality. Around 1940, he began planning a series of polytonal piano studies, for which he constructed a series of meticulous charts outlining their intended harmonic structures. Of the 46 studies he originally planned, Farwell completed only 23 before his death in 1952. Each study juxtaposes two keys—one in the treble clef, another in the bass clef—and at the top of each score, he indicates the relationship between the two keys using Roman numerals. For example, Polytonal Study, No. 1, labeled “I7 – V7, C – G,” juxtaposes C major seventh-chord harmonies in the bass against harmonies built on a G major seventh-chord in the treble. Theorists and pianists have responded to these studies with mixed criticism: Edgar Kirk observed that the studies are “often questionable” and the “polytonal” effect is generally lost in hearing the music [19], while Bruce Neely has praised the most effective of these studies as being “among his [Farwell’s] most original and beautiful works”[20]. Regardless, Farwell’s harmonic experimentation in the Polytonal Studies appears to have informed his one-movement Piano Sonata, op. 113 (1949), which features complicated chromaticism and intense technical challenges that, according to Neely, seem to push the instrument to its limits.[21]

11

The extended harmonic language featured in Farwell’s late piano works also makes an appearance in some of the composer’s vocal music from the same period, most notably in his settings of Emily Dickinson poems in Op. 108 (Ten Emily Dickinson Songs, 1944) and Op. 112 (Three Emily Dickinson Songs, 1949).

Throughout his life, Farwell turned frequently to Emily Dickinson’s poems and ultimately set 39 of her texts for solo voice and piano, composed individually or in various groups. His preference for her poetry was significant: the only other authors he returned to—William Blake and Percy Bysshe Shelley, for example—inspired at most five songs each. Moreover, Farwell was among the earliest composers to use her poetry, completing his The Sea of Sunset, op. 26 (1907), just 17 years after the Boston publishing firm Roberts Brothers issued the first collection of Dickinson’s work, albeit in highly edited form (Emily Dickinson, Poems, 1890). Farwell’s other early Dickinson settings in the 1920s—Op. 66 (Two Poems by Emily Dickinson, 1923) and Op. 73 (Two Emily Dickinson Poems, 1926)—formed what Gerald Holmes called a “‘trickle’ of early, obscure, unrecorded settings” of her poems that quickly “reached flood level after settings by Elliott Carter, Ned Rorem, and Aaron Copland entered the canon” in the 1950s and 1960s.[22]

Although Farwell’s early Dickinson songs were published by G. Schirmer in the 1920s, the firm declined to issue his later settings and, in the late 1940s, even destroyed the remaining copies of Farwell’s other songs in their catalog when sales dwindled.[23] Years after Farwell’s death, his Dickinson songs were rediscovered by tenor Paul Sperry, who championed them in recitals, recordings, and (finally) a 2-volume edition with 33 of Farwell’s previously unpublished Dickinson songs (Boosey & Hawkes, 1983).

Recent analyses and critiques of Farwell’s late Dickinson songs count them among the best of the composer’s works, with critics highlighting in particular the expressive conviction and harmonic originality in his settings. He employs colorful chromaticism, opulent harmonies, chains of extended and secondary chords, even moments of (what Neely Bruce has called) “non-simultaneous polytonality” to evoke the tension, movement, and emotional depth of Dickinson’s texts.[24] The first song of Op. 112, “Wild Nights! Wild Nights!,” is a prime example of Farwell’s approach: the ascending chromaticism of the opening bass line, combined with the rhythmic juxtaposition of triple and duple figures, evokes the underlying agitation of Dickinson’s evocative text. As the speaker’s desire grows, the vocal line continues to rise against an increasingly frantic accompaniment that builds to a dramatic, fortissimo climax at the poem’s passionate denouement—“might I but moor tonight in thee!”

Certainly, Farwell’s experimentation in these works—and across his oeuvre—pales in comparison with that of avant-garde modernists like Arnold Schoenberg (1974–1951), Edgard Varèse (1883–1965), and Henry Cowell (1897–1965). Farwell himself often remarked that he felt disconnected from his contemporaries, which is unsurprising given his anti-establishment views, preference for Romantic-style harmonies, and general gravitation toward musical populism.[25] Nevertheless, recent assessments of Farwell’s music and impact have highlighted the ways in which he prefigured various trends and developments in American composition and musical life at large.[26]

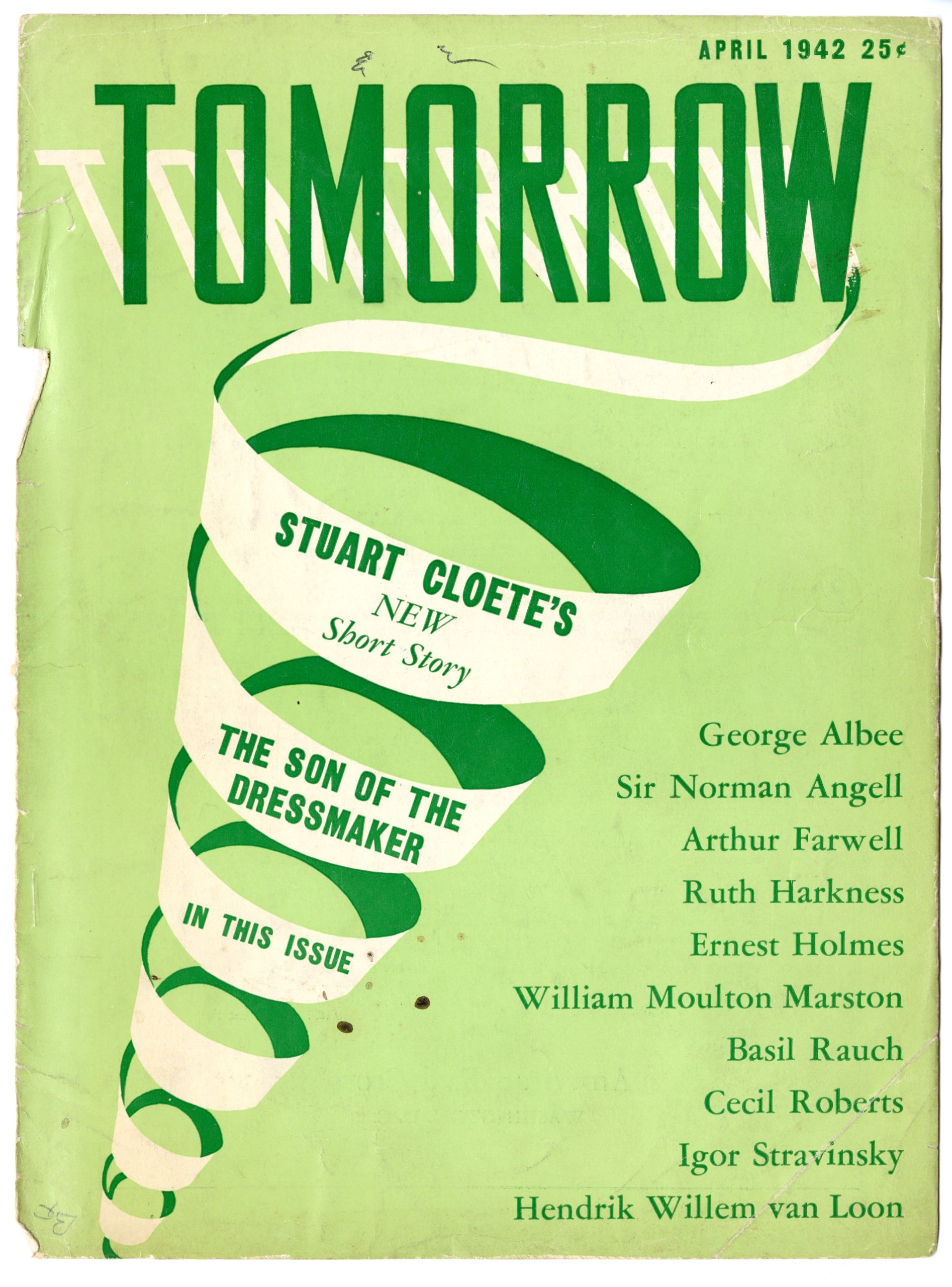

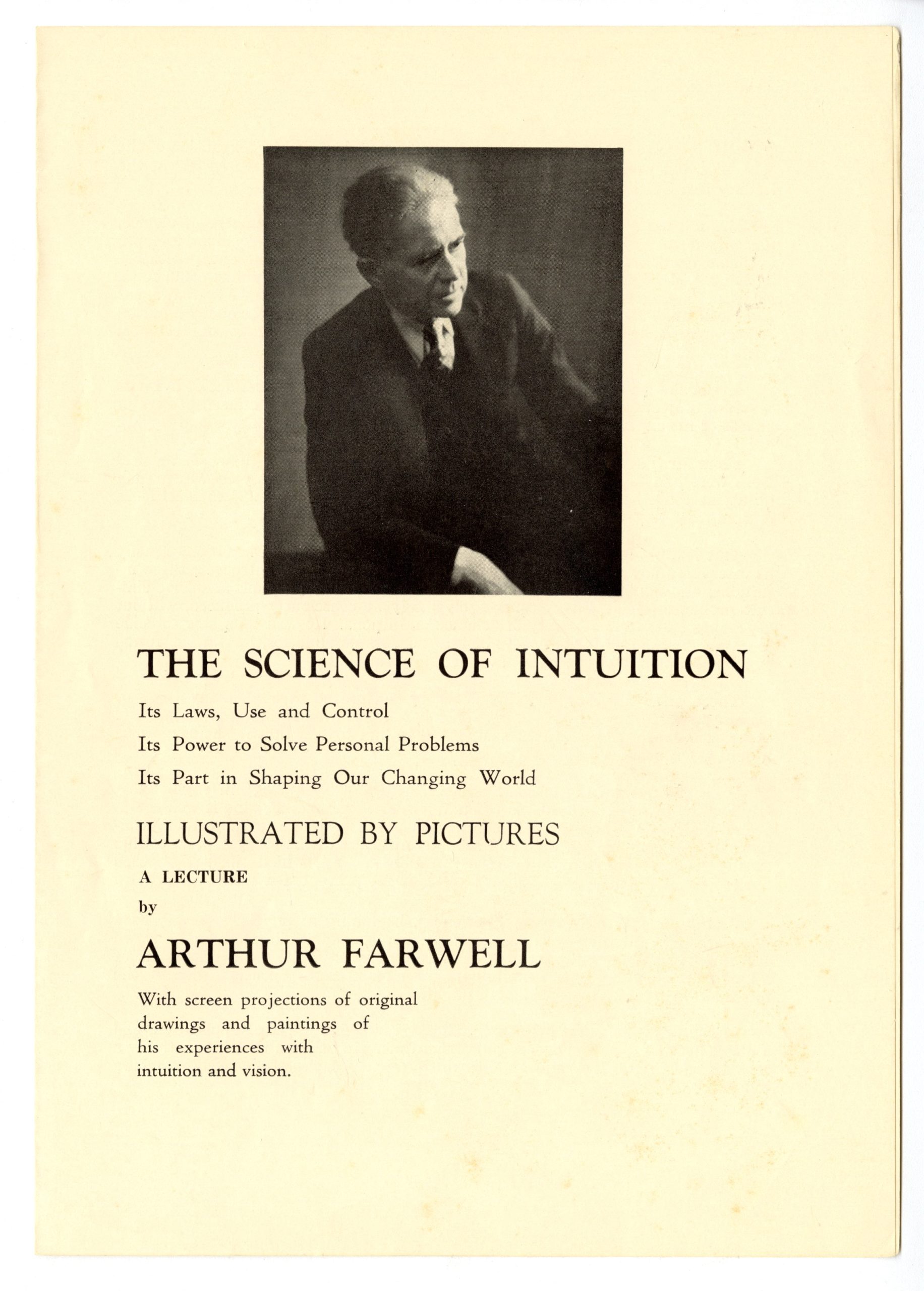

12

Farwell’s other major retirement project was a book on “intuition,” a philosophical concept that was central to the composer’s creative process. In an article for Tomorrow magazine[27], Farwell explained that intuition, or the “immediate insight into truth,” comes in many different forms—“the ‘hunch,’ the sudden flash of insight, the ‘inspiration’ of one kind or another, the symbolic dream, and other related phenomena.” As a subjective feeling, impulse, or perception, intuition occurred “without an immediate process of reason, revealing the inward nature and sometimes the solution of life-problems.” The knowledge derived from intuition was “entirely beyond the reach of the ordinary waking mind,” but an individual could train themselves to perceive their intuitive consciousness and access these otherwise hidden thoughts and inspirations.[28] One could even inspire intuitive visions and dreams through focused meditation. In this, Farwell was influenced by Transcendentalism, which similarly emphasized subjective intuition over logical reasoning, as well as principles from Theosophy and the New Thought movement, which also elevated intuition as a means of accessing otherwise unknowable, inner truths.[29]

In the Tomorrow article, Farwell describes firsthand how he was able to channel intuition in his compositional process:

I conceived, in a half-fanciful way, that the universe must contain somewhere or somehow all the musical ideas which had never yet been thought of and written down. I believed that if I could find the right means of access to this universal store, I could put my hand at once on any musical themes I needed. To attempt this I thought of a ‘place of music,’ where the universe concentrated all these ideas, and where they could be had on application. I imagined a great assemblage of all possible means of producing music, a universal orchestra, including all instruments, and a chorus. … As definitely as possible, I then thought of the particular kind of theme I needed … I watched the musical equipment of the universal store I created … keeping out of my mind every thought except the one on which I had concentrated. It required only a moment before the appropriate theme spoke out from the appropriate instrument or instruments, apparently wholly by its own volition, and absolutely without any effort of composition on my part. …

I have continued to use this direct procedure for twenty years in the solution of difficult problems of life beyond the power of my reasoning faculty to answer, with highly successful and often astonishing results.[30]

13

Farwell developed his theories about creative intuition over a lifetime. Through his mother, he was exposed to Theosophy and other esoteric philosophies as a child and young man, and as an adult, he was attracted to the teachings of New Thought authors like Thomas Troward (1847–1916). As early as 1913–1914, Farwell recommended Troward’s writings in articles for Musical America and acknowledged their influence on his own artistic philosophy.[31] In Farwell’s later years, he began gathering a collection of newspaper articles and book reviews related to intuition and psychology from both mainstream newspapers and some more esoteric sources (e.g., The American Theosophist). [32] He was especially interested in the experiences and writing of other writers, artists, and composers who adopted esoteric spiritual practices or had been influenced by dreams or visions as part of their creative process, such as William Blake (1757–1827) and Alexander Scriabin (1872–1915). Around 1930, while still teaching at Michigan State, Farwell began compiling his thoughts into a comprehensive treatise on intuition, which he titled “Intuition in the World-Making.” After his retirement, he prepared a new lecture on “The Science of Intuition,” which was based on material from his book. The presentation also featured screen projections of original drawings and watercolors that depicted scenes from his own intuitive dreams and visions.[33]

As Judith Tick has noted, Farwell’s interest in Western esoteric philosophies and Troward’s “mental science” was hardly unique among early 20th-century composers and artists. Beyond Farwell, Ruth Crawford Seeger (1901–1953), Charles T. Griffes (1884–1920), and Henry Cowell (1897–1965), among others, embraced and were influenced by Theosophy, Eastern religion, and other esoteric philosophies.[34] More broadly, the late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed an increasing interest in occultism, mysticism, and the supernatural, which, as several cultural historians have noted, influenced the emergence and evolution of modernism across the arts in both the United States and Europe.[35] A growing body of scholarship has analyzed traces of this “occult modernism” in the works of visual artists and writers like Wassily Kandinsky, Hilma af Klint, and Ezra Pound.[36] Given Farwell’s extensive writing on his philosophy of intuition and his statements on the central role it played in his artistic process, his oeuvre presents another rich field site for examining this cultural trend in early 20th-century American music.

14

Farwell remained active as a composer and teacher until his death on January 20, 1952, a few months before his 80th birthday. He left behind an eclectic legacy represented not only in his own compositions and writings but also through his wide-ranging involvement in diverse artistic and cultural movements, organization of innovative public performances and performance spaces, and leadership in various music and performing arts organizations. For much of his life, Farwell was constantly on the move, working tirelessly on one project or another. Yet, as Beth Levy remarked, “Farwell was better at beginning projects than continuing them,” noting that most of his numerous endeavors—from music publishing to community choruses and pageants—were short-lived, in part due to ever-present financial constraints and Farwell’s ongoing family obligations.[37] Nevertheless, he persisted in his vision for a robust, modern American musical landscape that would stand apart from European, and specifically Germanic, musical trends and styles. Tracing Farwell’s career, including his compositions, writings, and professional projects, highlights how the composer reacted to and embraced the whirlpool of artistic, socio-cultural, political, and religious influences that cut across American society in the early 20th century.

[1] A small collection of manuscript scores by Arthur Farwell (totaling 19 scores) is kept at the New York Public Library.

[2] Farwell, quoted in Evelyn Davis Culbertson, He Heard America Singing: Arthur Farwell, Composer and Crusading Music Educator (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1992), 657. Call number: ML410.F247 C96 1992.

[3] For more on Farwell’s musical evocations of the American landscape, and particularly the American West, see Beth Levy, “The Wa-Wan and the West,” chap. 1 in Frontier Figures: American Music and the Mythology of the American West (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012). Call number: ML200.5.L6682 F93 2012.

[4] Tara Browner, “‘Breathing the Indian Spirit’: Thoughts on Musical Borrowing and the ‘Indianist’ Movement in American Music,” American Music, vol. 15, no. 3 (Autumn 1997): 266. Available via JSTOR.

[5] Farwell, quoted in Edward N. Waters, “The Wa-Wan Press: An Adventure in Musical Idealism,” in A Birthday Offering to [Carl Engel], ed. Gustave Reese (New York: G. Schirmer, 1943), 219. Call number: ML55.E5 R329.

[6] Arthur Farwell, “Toward American Music,” Out West, vol. 20, no. 5 (May 1905): 457; reprinted in “Wanderjahre of a Revolutionist” and Other Essays on American Music, ed. Thomas Stoner (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 1995), 188–189. Call number: ML410.F247 A3 1995.

[7] Levy, Frontier Figures, 31.

[8] From the organization’s mission statement, as printed in The Wa-Wan Press Monthly, vol. 6, no. 43 (March 1907): 1; reprinted in The Wa-Wan Press, 1901–1911, ed. Vera Brodsky Lawrence, vol. 4 (New York: Arno Press, 1970), 29–30. Call number: M2 .L423W.

[9] The history of the individual centers, and the life span of the Society, is difficult to track after the dissolution of the short-lived Bulletin of the American Music Society, which replaced the Wa-Wan Press Monthly in 1908; the Bulletin only produced four issues, the last printed in March 1909. However, Evelyn Davis Culbertson notes that the American Music Society grew to about 20 centers by 1909 (according to Farwell). Culbertson, He Heard America Singing, 139–146, 791n16.

[10] Arthur Farwell, “The New Gospel of Music – I,” Musical America, no. 19 (April 4, 1914), 32; reprinted in “Wanderjahre of a Revolutionist” and Other Essays on American Music, 222–226.

[11] David Glassberg, American Historical Pageantry: The Uses of Tradition in the Early Twentieth Century (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990), 1. Call number: PS338.H56 G5 1990.

[12] Arthur Farwell, “Pageant Music,” Bulletin [of the American Pageant Association], no. 43 (December 1, 1916): 1. Available via HathiTrust.

[13] Arthur Farwell, “The New Gospel of Music,” Musical America, vol. 19 (April 4, 1914): 32; reprinted in “Wanderjahre of a Revolutionist” and Other Essays on American Music, 222–226.

[14] Notably, Barnhart and Farwell collaborated closely in the organization and direction of the New York Community Chorus, with Barnhart serving as its director and Farwell as its first president.

[15] Claude Bragdon, “ ‘Song and Light’; A Description of an Outdoor Festival Given at Highland Park, Rochester, NY, September 30, 1915,” Architectural Review, vol. 4, no. 9 (September 1916): 169–171. Available via HathiTrust. See also Jonathan Massey, “Organic Architecture and Direct Democracy: Claude Bragdon’s Festivals of Song and Light,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 65, no. 4 (December 2006): 578–613. Available via JSTOR.

[16] “Where the Arts Combine,” The Playground, vol. 19, no. 12 (March 1926): 675. Available via HathiTrust.

[17] Culbertson, He Heard America Singing, 625.

[18] Culbertson quotes from multiple letters from Farwell in which he complains about his course load at Michigan State. See Culbertson, He Heard America Singing, 232–235.

[19] Edgar Lee Kirk, “Toward American Music: A Study of the Life and Music of Arthur George Farwell” (PhD diss., University of Rochester, 1958), 143. Call number: ML95.3.K59.

[20] Gilbert Chase, revised by Neely Bruce, “Farwell, Arthur,” Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, January 20, 2001,.

[21] Quoted in Culbertson, He Heard America Singing, 521.

[22] Gerald Holmes, “‘Invisible, as Music–’: What the Earliest Musical Settings of Emily Dickinson’s Poems, Including Two Previously Unknown, Tell Us about Dickinson’s Musicality,” Emily Dickinson Journal, vol. 28, no. 2 (2019): 101. Available via Project MUSE

[23] In a May 26, 1948, letter to Noble Kreider, Farwell lamented, “None of the current generation of artists ever heard of me, especially as the leading orchestra conductors will no longer play anything of my generation. And now Schirmer is going to destroy the bulk of the plates of my songs which they publish, unless I will buy them from them, (which I can’t do), and the few remaining copies. … Yet I feel that they represent a lot of my finest work, and in the long run would prove a real contribution to American song literature.” Quoted in Culbertson, page 445–446. Original in the Arthur Farwell Collection, Box 37/27.

[24] Neely Bruce, review of Thirty-Four Songs on Poems of Emily Dickinson, Notes, vol. 42, no. 2 (December 1985): 409. Available via JSTOR .

[25] Farwell wrote at length about his dissatisfaction with the contemporary trends in American composition and the music industry at large in articles, lectures, and private writings; he even composed a satirical opera, Cartoon or Once upon a Time Recently (1948), that explicitly critiques European modernism through musical satirizations of Schoenberg and Stravinsky. See, for example, a lengthy letter Farwell wrote to his student, Roy Harris, which Culbertson printed in her biography. Culbertson, He Heard America Singing, 262–269. Original in Farwell Collection, Box 34, Folder 4.

[26] See, for example, Chase, rev. Bruce, “Farwell, Arthur,” ; Culbertson, He Heard America Singing, 350–355 ; Thomas Stoner, “‘The New Gospel of Music’: Arthur Farwell’s Vision of Democratic Music in America,” American Music, vol. 9, no. 2 (Summer 1991): 184. Available via JSTOR.

[27] Tomorrow magazine was an American literary journal that specialized in articles on parapsychology and the paranormal. It was founded by parapsychologist and medium Eileen J. Garrett and published through Garrett’s Creative Age Press and the Parapsychology Foundation during the 1940s–1960s.

[28] Arthur Farwell, “Science and Intuition,” Tomorrow, vol. 1, no. 8 (April 1942): 20–21. Arthur Farwell Collection, Box 24, Folder 16.

[29] Specifically, Farwell was deeply inspired by the writings of New Thought pioneer Thomas Troward, particularly those on “mental science” and the creative process. According to Thomas Stoner, Farwell likely came across Troward’s writings in 1911, and Farwell referenced Troward’s writings in several articles for Musical America in 1913 and 1914. Stoner, “‘The New Gospel of Music’”: 189–190.

[30] Arthur Farwell, “Science and Intuition,” Tomorrow, vol. 1, no. 8 (April 1942): 23–24. Arthur Farwell Collection, Box 24, Folder 16.

[31] Stoner, “‘The New Gospel of Music’”: 205.

[32] Farwell’s collection of newspaper clippings related to intuition is preserved in the Arthur Farwell Collection, Box 24, Folder 10.

[33] Between 1943 and 1949, Farwell produced multiple complete and partial drafts of his book on intuition, several of which are preserved in the Arthur Farwell Collection, Boxes 25–28. Farwell’s efforts during his life to find a publisher for the treatise proved unfruitful, as did those of his wife, Betty Richardson Farwell, in the years immediately following her husband’s death. However, Farwell’s treatise may yet be published: an edition of Farwell’s Intuition in the World-Making is currently being prepared by Dr. Matt Marble under commission by the composer’s son, Jonathan Farwell.

[34] Judith Tick, “Ruth Crawford: Modernist Pioneer,” in Ruth Crawford, Music for Small Orchestra (1926) [and] Suite No. 2 for Four Strings and Piano (1929), vol. 1 of Music of the United States of America (Madison, WI: A-R Editions, 1993), xvii. Call number: M 2 .R2947A v.19. See also Judith Tick, “Ruth Crawford’s ‘Spiritual Concept’: The Sound-Ideals of an Early American Modernist, 1924–1930,” Journal of the American Musicological Society, vol. 44, no. 2 (Summer 1991): 221–261. Available via JSTOR.

[35] For more on the intersections between occultism, esoteric practices, and modernism, see Tessel M. Bauduin and Henrik Johnsson, eds., The Occult in Modernist Art, Literature, and Cinema (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018) Call number:; Roger Lipsey, An Art of Our Own: The Spiritual in Twentieth-Century Art (Boston: Shambhala, 1988) Call number: N8248.S77 L56 1988 ; Maurice Tuchman, Judi Freeman, and Carel Blotkamp, eds., The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890–1985, exhibition catalogue, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (New York: Abbeville Press, 1986) Call number: ND192.A25 S6 1986.

[36] Tessel M. Bauduin, “The Occult and the Visual Arts,” in The Occult World, ed. Christopher Partridge (New York: Routledge, 2014): 429–445. Ebook available. ; Leon Surette, The Birth of Modernism: Pound, Yeats, Eliot and Occult Modernism (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993). Call number: PN56.M54 S77 1993.

Audio Excerpts

“A Celebration of Arthur Farwell,” concert by various ESM student and faculty performers (1997). Streaming audio available to UR/ESM community.

Farwell, A.: Piano Music, Vols. 1–3, Lisa Cheryl Thomas, piano (Toccata Classics, 2012–2018). Streaming audio available via NAXOS.

Farwell, A.: Songs, Choral and Piano Works (America’s Neglected Composer), Dakota String Quartet; William Sharp, baritone; University of Texas Chamber Singers; Emanuele Arciuli, piano (Naxos, 2021). Streaming audio available via NAXOS

The Gods of the Mountains Suite, Op. 52, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Karl Krueger (Bridge Records, 2003). Available via YouTube.

More from Sibley

He Heard America Singing: Arthur Farwell, Composer and Crusading Music Educator by Evelyn Davis Culbertson. Call number: ML410.F247 C96 1992

The Wa-Wan Press, 1901–1911, modern edition of the music published by the Wa-Wan Press in 5 volumes, prepared by Vera Brodsky Lawrence. Call number: M2 .L423W

Wanderjahre of a Revolutionist and Other Essays on American Music by Arthur Farwell, edited by Thomas Stoner. Call number: ML410.F247 A3 1995

Scores by Arthur Farwell in DiscoverUR.

For further information, please inquire at the Ruth T. Watanabe Special Collections department.

A full finding aid for the Arthur Farwell Collection is available online.