Published on Feb 7th, 2023

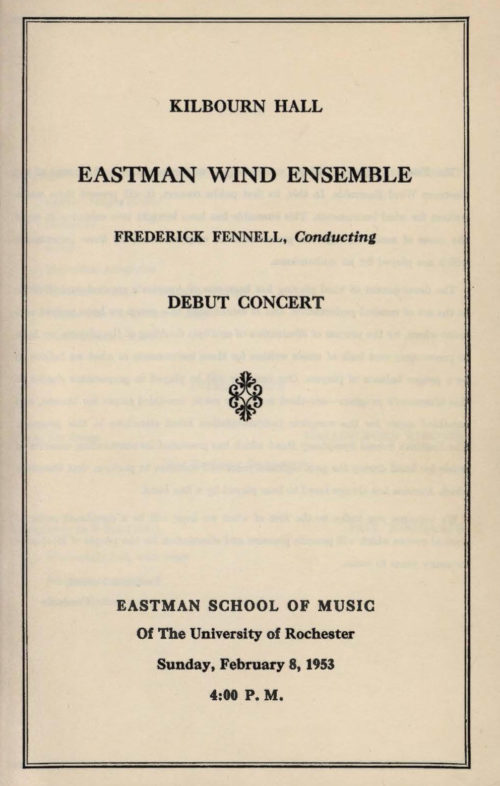

Seventy years ago this week, on the afternoon of Sunday, February 8th, 1953, the Eastman Wind Ensemble made its public debut with a concert in Kilbourn Hall, opening with these bars of music from the Serenade no. 10 in B-flat by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

It is surely no exaggeration to say that the concert marked not only a milestone for the Eastman School of Music, but also the start of a new era in winds and brass performance. Besides giving exposure to a newly founded ensemble, the concert explicitly promoted the wind ensemble concept which would be enthusiastically embraced in the ensuing years, both at home and abroad. The date of February 8th, 1953 might therefore to be taken to draw a clear line of demarcation in the chronological sweep of Eastman School history.

Accounts of the Eastman Wind Ensemble’s founding have been published, in greater and in lesser detail; [1] in addition, Frederick Fennell set out his vision for the wind ensemble concept in his book Time and the Winds (Leblanc, 1954). For the purposes of this entry, I will share that Frederick Fennell’s interest in bands had been a lifelong concern, dating back to his boyhood summers at the National Music Camp (Interlochen, Michigan) and his activities as drum major in the marching band at John Adams High School in his native Cleveland. From the Eastman School he wrote to one of his mentors, renowned band director Albert Austin Harding (1880-1958), “I am all for bands and you know that is where I intend to do my work.”[2] An industrious undergraduate, the young Fennell founded the University of Rochester’s first-ever marching band—while still a freshman—and then, when the football season had ended, brought the band indoors to become the University of Rochester Symphony Band.[3] After receiving his masters degree in 1939, Fennell was appointed to the Eastman School faculty, where throughout the 1940s (apart from three years’ national service during World War II) and into the ‘50s, he would be concerned with both teaching and conducting. In 1950 Fennell won administrative support to organize what he called the Kilbourn Hall Wind/Brass Program, whereby he regularly rehearsed the school’s reed, brass, and percussion performers in repertory tracing the development of wind literature. This activity, together with his work with the Symphony Band, proved to be pivotal in his motivation to eventually found a new ensemble for winds. As he would later write,

A few decades of industry on the part of some composers and a few bandmasters had stimulated genuine interest in the creation of contemporary music for the wind band, but the mere existence of this music did not guarantee its performance, proper or otherwise. It was my concern that, for want of proper performance, this hard-won interest by composers of our time would be lost, thus robbing the wind-band medium of its greatest chance for artistic acceptance and survival. These observations seemed to call for a new kind of ensemble. There was the unique American gift for artistry of the highest caliber on the wind and percussion instruments and our incredibly well-organized systems for attracting the youth of the land to the teaching of these instruments. The unprecedented participation of millions of school children in band activity was both system and result. This vast and churning activity, consuming the daily musical thoughts of millions of people, seemed in need of a fresh, imaginative, and responsible approach. It was our further conviction that matters of instrumentation have always been the province of composers rather than committees; the music to be played would be the only factor to govern the choice of instruments that would be assembled.[4]

—Thus, already in Fennell’s work at Eastman there were signs pointing to the future. Both the Symphony Band and the Kilbourn Hall Winds/Brass program were vehicles by which Fennell introduced to the Eastman School audience works that would eventually be performed and recorded by the Eastman Wind Ensemble in its first decade.[5] In particular, a concert of music for wind instruments on February 5th, 1951 featured performances of works that would later be prominent vehicles in the Eastman Wind Ensemble’s repertory.[6] The success of that concert was one more inflection point in the long progression of Fennell’s deliberations towards founding a new ensemble for winds.[7]

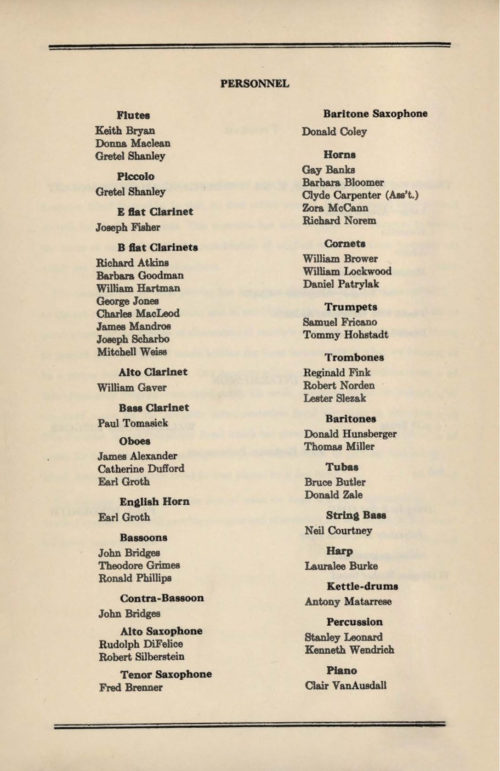

Fennell would articulate his vision for the one-to-a-part wind ensemble just a few years later in his book Time and the Winds, in which he commented at length on the wind band’s instrumentation, its role in music education, and its position in professional and community life. Far from replacing the college or university concert band, Fennell insisted that the wind ensemble could actually supplement it through offering students additional training and experience, as well as the important sense of “individual responsibility which is, perhaps, the greatest advantage of a small and intimate ensemble.” The time had come, Fennell reasoned, “. . . for the wind instruments to own a home of their own, unmortgaged by the limitations and traditions of other properties in which they have resided for so long.”[8] Fennell’s intention in founding the EWE was to meet what he perceived as the need for an ensemble of virtuoso caliber possessing the forces necessary to perform every type of music written for winds. His intention was to keep the instrumental forces as simple as possible; to that end, the ensemble would utilize no more than 45 players at its maximum. The resulting wind-brass-percussion corps would permit an almost limitless number of combinations of the three constituent groups in both large and small instrumentations. As Fennell pointed out in Time and the Winds, the Eastman Wind Ensemble’s instrumentation would constitute the same orchestra for which Wagner scored Der Ring des Nibelungen, and which Wagner assembled at Bayreuth in 1876, together with a saxophone section and one alto clarinet, and minus one bass trumpet — the same wind section which Stravinsky used in 1911 for Le Sacre du Printemps. Such an instrumentation would enable the performance of all music written for wind instruments from the 16th century through the 20th century.

All in all, Frederick Fennell was busy at Eastman in the early 1950s. He was teaching orchestral conducting; he was responsible for leading the Eastman School Symphony Band, the Eastman School Junior Symphony Orchestra, and the Eastman School Little Symphony[9]. In addition, he was directing the Kilbourn Hall Winds/Brass program already mentioned, and in the summer of 1952, he directed the Eastman School Summer Orchestra.[10]Amidst all of this professional activity came the new ensemble, the development of which had been building for some time in Fennell’s reflections. An event in Fennell’s personal life, namely a bout with hepatitis, proved to be another pivotal inflection point, for during his extended convalescence in hospital and then at home, Fennell wrote down his thoughts regarding a new ensemble for winds at Eastman, and then sharing those thoughts with Dr. Howard Hanson, who came to visit Fennell one day. In Fennell’s recollection, Hanson consented to the idea that same day.[11] Returning to active duty at Eastman in April, 1952, Fennell set about executing his plans for a new ensemble, which included writing to composers around the world to solicit their interest in composing for the wind ensemble. He also had a formative meeting with David Hall, director of classical music at Mercury Records, resulting in a plan to eventually record the as-yet unfounded Eastman Wind Ensemble.[12]

In September, 1952 Fennell called the first Eastman School Ensemble rehearsal, and from the outset, the new ensemble rehearsed four days a week. As Fennell would later recount:

It (i.e. the EWE’s rehearsal schedule) was always the same. It was never five days a week, always four days a week—Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday. Wednesday was the Symphony Band one hour rehearsal. Rehearsals were always 50 minutes long — 10 past one until 2 o’clock. We couldn’t have rehearsed any time longer than that. It was so intense. For those 50 minutes, those players in those groups gave, and thought and listened and concentrated. That was the hottest 50 minutes that you can imagine. We were into style, all the time style — and not only style. I tried, even then, to say to the players, look — I don’t think we should think about rehearsing for performances. I think we should rehearse to learn to play together. That’s a difficult thing for a lot of people to understand. Normally you are rehearsing for the concert. But the concert is only the result of how the group plays together. How they think about each other. …We don’t really rehearse a concert. we rehearse sound and playing together. We rehearse to become, every time, an ensemble. And the Eastman kids, they jumped into that concept right away.[13]

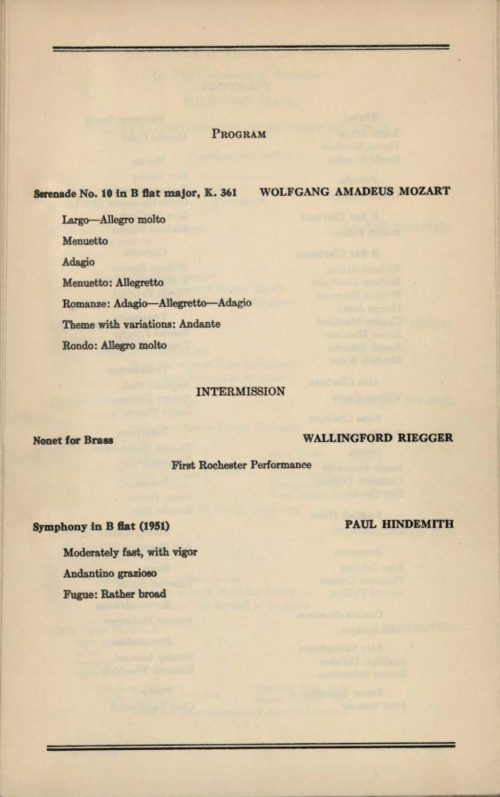

The programming of the 1953 debut concert reflected what would remain Fennell’s routine practice in EWE programming: one-third of the program scored for winds (in this instance, the Mozart), one-third for brass (the Riegger), and one-third for the combination of winds, brass, and percussion (the Hindemith). Two of those works would prove to be particularly significant for the EWE in the years ahead; the Mozart and the Hindemith would quickly become staples in the EWE’s active repertory, and were later recorded by the EWE for release on the Mercury Records label.[14] In addition, Fennell later made his own performing edition of the Mozart Serenade no. 10 (published by Ludwig Music Publishing, 1993). The debut concert’s programming was further representative of EWE programming to come in that old and new shared billing on one and the same concert program, that is, acknowledging tradition and legacy alongside promoting new repertory.

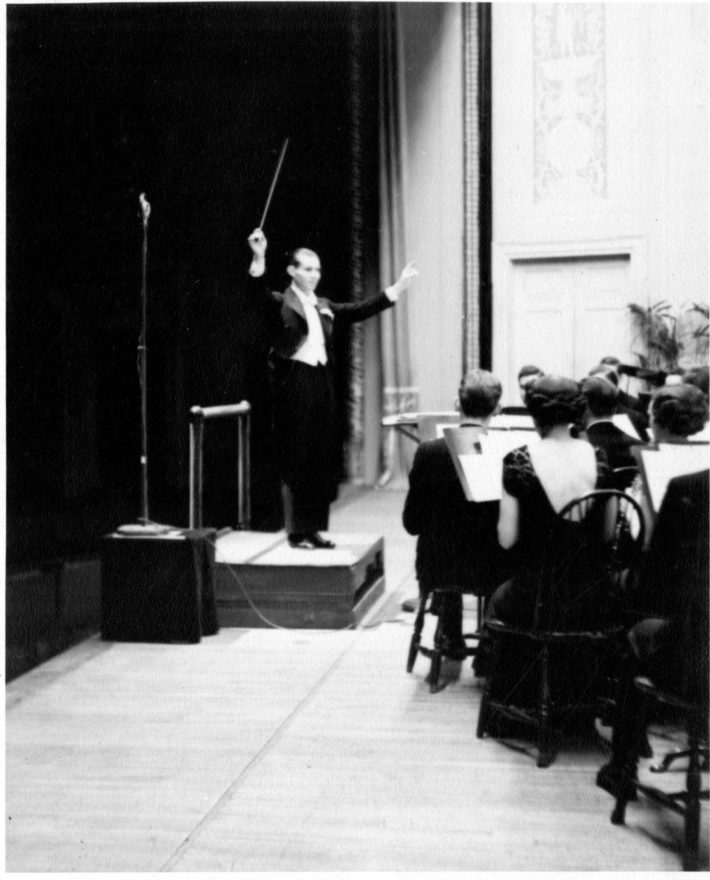

No photographs from the February 8th, 1953 debut concert are known to be extant; the archival coverage preserved at the Eastman School consists of little more than the printed program (displayed here), the master audio tapes, and copies of two local press reviews. The concert was recorded on binaural tape, and the masters have been been digitally re-formatted more than once, thereby ensuring the content’s continuing viability as audio technology passes from one generation to the next.[15] The news coverage of the debut concert was purely local, for no reviewers from out of town were present. Unlike the Eastman School’s annual Festivals of American Music, when such well-known critics as Olin Downes, chief music of The New York Times, and other writers visited Rochester to review performances, the Eastman School’s regular concert programming was covered only by the local music writers from both of Rochester’s daily newspapers.[16] Nevertheless, the fact that this concert marked a debut was underscored by the announcement of same on the front of the printed program, and by Fennell’s welcome message printed inside the program. His closing paragraph, expressing his hope that the new Eastman Wind Ensemble would provide “pleasure and stimulation for the people of Rochester for many years to come,” might now be perceived as modest, given the success that the EWE would quickly come to enjoy.

In advance of the debut concert, the EWE had already been heard on the airwaves, for that fall semester the EWE had begun to record a series of seven educational programs for the New York State School Music Association (NYSSMA) which were broadcast over the Rural Radio Network (list of those broadcasts displayed here). Besides the radio broadcasts for NYSSMA, the EWE was also heard in two coast-to-coast NBC radio broadcasts, aired on February 23rd and on March 23rd. Altogether, the debut concert was one of three concert hall performances that the EWE would give that spring semester, the other two being a concert at the Eastman School’s 1953 Festival of American Music, and a lecture concert that Fennell conducted at the 7th annual Symposium of the International Federation of Music Schools, hosted by the Eastman School on March 17th-21st, 1953. At the end of that spring semester, on May 14th, 1953, the EWE assembled in the Eastman Theater for its first recording session for Mercury Records. The resulting album, American Concert Band Masterpieces, would be released in the U.S. the following October, representing the first of what would ultimately be 23 commercial releases between May, 1953 and May, 1962.[17] The Eastman Wind Ensemble’s fruitful relationship with Mercury Records was instrumental in launching the EWE on its trajectory to national renown by placing its sound in the nation’s living rooms. Further, those recordings were made by means of the most up-to-date recording technology commercially available at that time.

What with concerts, national radio broadcasts, educational radio programming, and commercial recording, the EWE had enjoyed a vibrant and bold first season. All the rest is history. In the seven decades since the 1953 debut concert, the Eastman Wind Ensemble has flourished under the direction of its four successive conductors, Frederick Fennell, A. Clyde Roller, Donald Hunsberger, and Mark Scatterday, and in its championing of new music, has represented the vanguard in programming for winds. That has been no small legacy. If you are on-site at the Eastman School, please drop in at the Sibley Music Library and visit the Eastman Wind Ensemble Room (4th floor), where a new display traces highlights of the EWE’s first seven decades.

► Printed program, debut concert on February 8th, 1953. Eastman School of Music Archives.

► A feature in the New York State School Music Association’s journal The School Music News detailed the seven educational broadcasts made by the Eastman Wind Ensemble in the winter of 1953.

[1] These include a description of the EWE published in The Eastman School of Music, 1947-1962, edited by Charles Riker (University of Rochester, c1963). That description, published without attribution, was written by Fennell and is among his papers in a binder filled with other documents on EWE personnel and programming, 1952-62. Typescript and three pages in length, an annotation in his hand calls it “my best statement about the EWE”. A longer, more informal personal narrative by Fennell was published in in Ffortissimo: A Bio-Discography of Frederick Fennell: the first forty years, 1953 to 1993 by Roger E. Rickson (Ludwig Music Publishing, 1993).

[2] The letter, written in the glow of elation after having conducted a University of Rochester Symphony Band concert, is in the Albert Austin Harding Papers at the University of Illinois. The Ruth T. Watanabe Special Collections holds a photocopy of same, provided in 1999 by the late Phyllis Danner, then-Archivist for the Sousa Archives for Band Music.)

[3] Frederick Fennell’s University of Rochester Symphony Band would become a credit-earning course at the Eastman School of Music in the fall of 1935. The Score 1937, pages 62-63, accessible here

[4] From Fennell’s three-page statement on the EWE [1962], later published without attribution (University of Rochester, 1963).

[5] To name three examples, Paul Hindemith’s Symphony in B-flat was performed by the Eastman School Symphony Band in 1952; it was later recorded by the Eastman Wind Ensemble in 1957. Samuel Barber’s Commando March was performed by the Eastman School Senior Symphony Band in 1947 and by the Eastman School Symphony Band in 1949; the Eastman Wind Ensemble first performed it in 1953 and included it on the first EWE commercial recording for Mercury Records, since which time it has been a staple in the EWE’s repertory. Stravinsky’s Symphonies for Wind Instruments had its Rochester premiere in 1951 by the students in Fennell’s Winds and Brass program; it would later be recorded by the EWE in 1957.

[6] These were Mozart’s Serenade no. 10 in B-flat, K. 361, Strauss’ Serenade in E-flat major, opus 7, and Stravinsky’s Symphonies for Wind Instruments (the Rochester premiere of the latter).

[7] A handwritten comment among Fennell’s papers confirms this fact.

[8] A copy of the book is in the Sibley Music Library stacks; in addition, a manuscript copy in Fennell’s hand resides in the Ruth T. Watanabe Special Collections.

[9] The Little Symphony Orchestra, initially founded as the Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia, was formally affiliated with the Alpha Nu chapter (installed at the ESM on January 24, 1924) of the national musical fraternity Phi Mu Alpha, hence its membership was initially restricted to members of the fraternity. The orchestra was founded by faculty member Samuel Belov, who served as its conductor 1926-29; he was succeeded by faculty member Karl Van Hoesen in the years 1930-38; Frederick Fennell succeeded Van Hoesen in 1938. The orchestra had quickly become integrated into the fabric of the Eastman School’s concert life with a tradition of giving three concerts a year, performing for national radio broadcasts in the 1920s and ‘30s, and also undertaking two long-distance tours in its first decade. In addition to performing the standard orchestral repertory, the Little Symphony contributed to the Eastman School’s recognition of American music by performing more than forty premiere performances. In one sense, Fennell’s association with the Little Symphony as its conductor was ready-made, for as an Eastman student (1933-39) he had been a Phi Mu Alpha man and a percussionist in the Little Symphony. From 1938 onwards he conducted the Little Symphony continuously with only a three-year leave of absence while fulfilling national service requirements during World War II.

[10] The Summer Orchestra appears to have been a forerunner of the summertime Eastman Chamber Orchestra that Fennell founded in 1954 and that he would direct until 1962.

[11] Rickson (1993).

[12] Ibid. The lifelong involvement of David Hall (1916-2012) with the U.S. recording industry is now legendary. As director of classical music at Mercury Records, he had had much to do with developing the Eastman School’s Mercury contract and recording program. He later served as editor of Stereo Review and was a founding member of the Association for Recorded Sound Collections.

[13] Ibid. This quotation comes from the section titled “How it all began: Conversation with Frederick Fennell, Siesta Key, Florida 17 August 1991.”

[14] The EWE performed both works in a gala 70th anniversary concert on January 27th, 2023, the programming emulating the debut concert’s programming: Mozart to open, Hindemith to close, with Valerie Coleman’s Fanfare for Uncommon Times slotted between them.

[15] The concert is accessible via streaming to the networked UR community; visit https://archive.esm.rochester.edu/ and enter “19530208” in the search query field in the upper right corner of the screen. The content consists of eleven tracks.

[16] In an earlier time, the music writers for both the Rochester Democrat & Chronicle and Rochester Times-Union used to review student performances such as concerts by the Eastman School’s orchestras, symphony band, operatic productions, and eventually the Eastman Wind Ensemble.

[17] Dr. Reed Chamberlin offers an excellent examination of the EWE on the Mercury Records label in his article “Hi-Fi, Middle Brow? Frederick Fennell, Mercury Records, and the Eastman Wind Ensemble from 1952 to 1962” published in SAGE Open, vol. 10, no. 4 (October-December 2020). Accessible online to subscribing parties.