Published on Nov 14th, 2022

Carnegie Hall. The name uttered with utmost respect and with fond aspiration. The dream destination of every serious performing artist, restricted to all but the very best, and representing the standard of excellence in any genre. Tchaikovsky, Mahler, Dvořák, Bartók, Gershwin, Van Cliburn, Vladimir Ashkenazy, Itzhak Perlman, Renee Fleming, Billie Holiday, Benny Goodman, Judy Garland, The Beatles, Elton John, Bruce Springsteen . . . since 1891, these and many more of their caliber have crossed the stage of Carnegie Hall, and to stand in their company is to have reached a sure summit of success. This week we mark two anniversaries of the first-ever Carnegie Hall appearances by two Eastman School ensembles, for sixty-one years ago, on the evening of Friday, November 17th, 1961, the Eastman Wind Ensemble performed before a capacity audience of 2,200; one year later (almost to the day), on the evening of Friday, November 16th, 1962, the Eastman Philharmonia made its own first appearance at Carnegie Hall. Neither photographs nor recordings of either concert are extant, but sufficient documentation survives to share something of the experience and the enthusiastic audience reception of each night. For the EWE, the Carnegie Hall engagement provided a punctuation to the EWE’s first decade, a span of years that had brought a national reputation, commercial success, and critical acclaim. For the Eastman Philharmonia, the Carnegie Hall engagement was a fitting legacy of the orchestra’s landmark tour of Europe, the Middle East, and the Soviet Union the previous winter.

1961: The Eastman Wind Ensemble

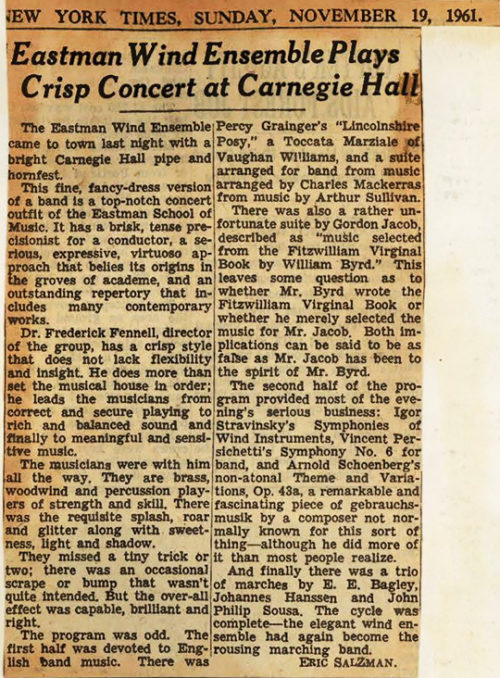

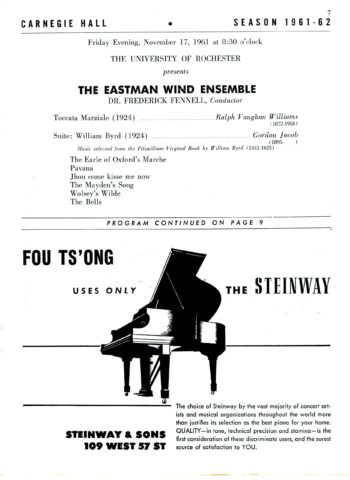

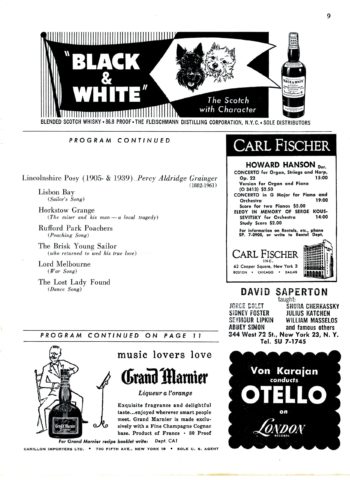

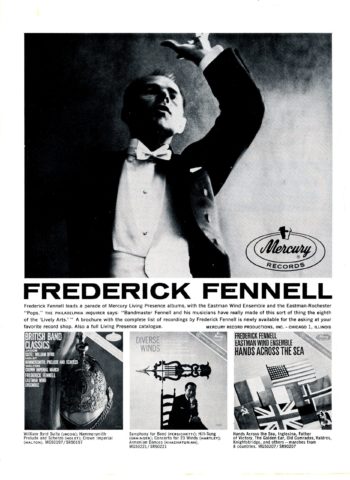

The adjective “crisp” is perhaps the primary take-away from Eric Salzman’s review that appeared in The New York Times on Sunday, November 19th, 1961. This was no ordinary winds group, this Eastman Wind Ensemble! With its reputation for finesse and precision—yes, crisp playing!—the EWE had established itself as a winds performance model to be emulated. This was definitely one for the history books, in two respects. For the Eastman School of Music, the concert marked the first-ever engagement by an Eastman ensemble in that venue. For the Eastman Wind Ensemble, the concert represented the culmination of a decade of development and achievement, a fitting milestone. Under Fennell’s direction, the EWE had quickly gathered momentum following the first rehearsal on September 20th, 1952.[1] In the first two seasons (1952-53 and 1953-54), the regularly scheduled home concerts had been accompanied by twelve concerts for the New York State School Music Association that were broadcast via the Rural Radio Network, as well as two coast-to-coast NBC radio broadcasts. In addition, there were out-of-town engagements in Chicago for CBDNA (1954), Atlantic City for MENC (1960), and at Vassar College for the College’s centennial (1961). Besides all of this activity, the EWE had won a smashing contract with Mercury Records that ultimately provided for the release of nearly two dozen recordings between 1953 and 1962, thereby exporting the EWE’s new and innovative sound into the nation’s living rooms in high-fidelity stereophonic sound. By 1961 the EWE was ready for its New York City debut with a specially chosen program that would showcase several aspects of the ensemble’s mission: paying homage to the English winds and band tradition; celebrating some new and innovative writing for winds based on folk music, and also the heady growing repertory of 20th-century winds music; and finally, acknowledging that most ubiquitous genre without which the winds repertory would not be complete: the march. Commenting on the program, Frederick Fennell was quoted as saying that it was “. . .designed to encompass the high points in the emergence of the wind band during the second quarter of the 20th century, as a challenging medium of musical expression.”[2]

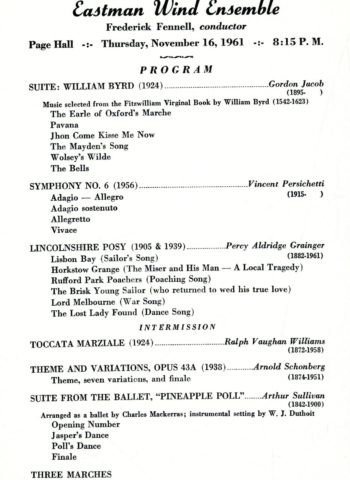

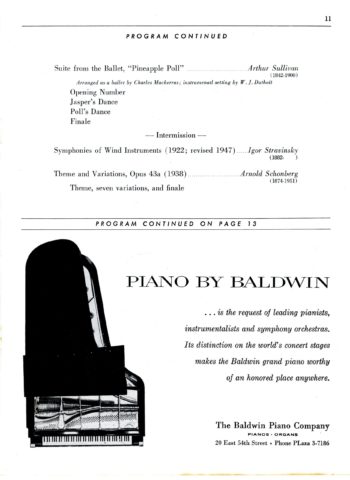

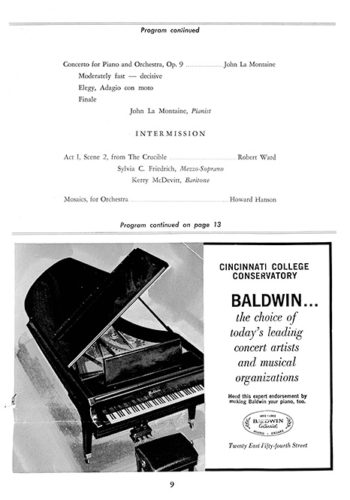

► Program from the EWE concert at Carnegie Hall, November 17th, 1961. Then as now, a concert program in a professional venue was likely to be chock-full of advertising. Frederick Fennell Collection.

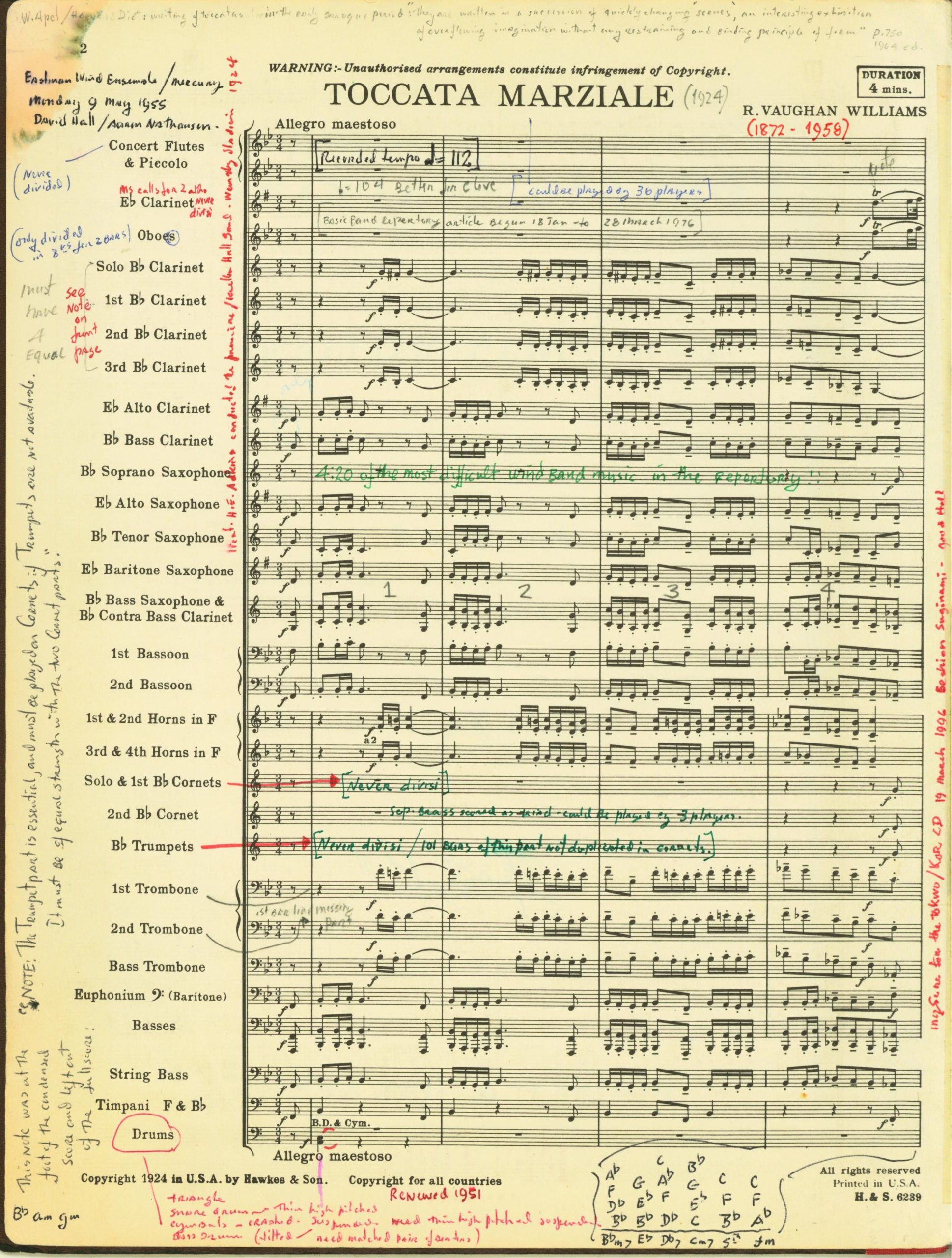

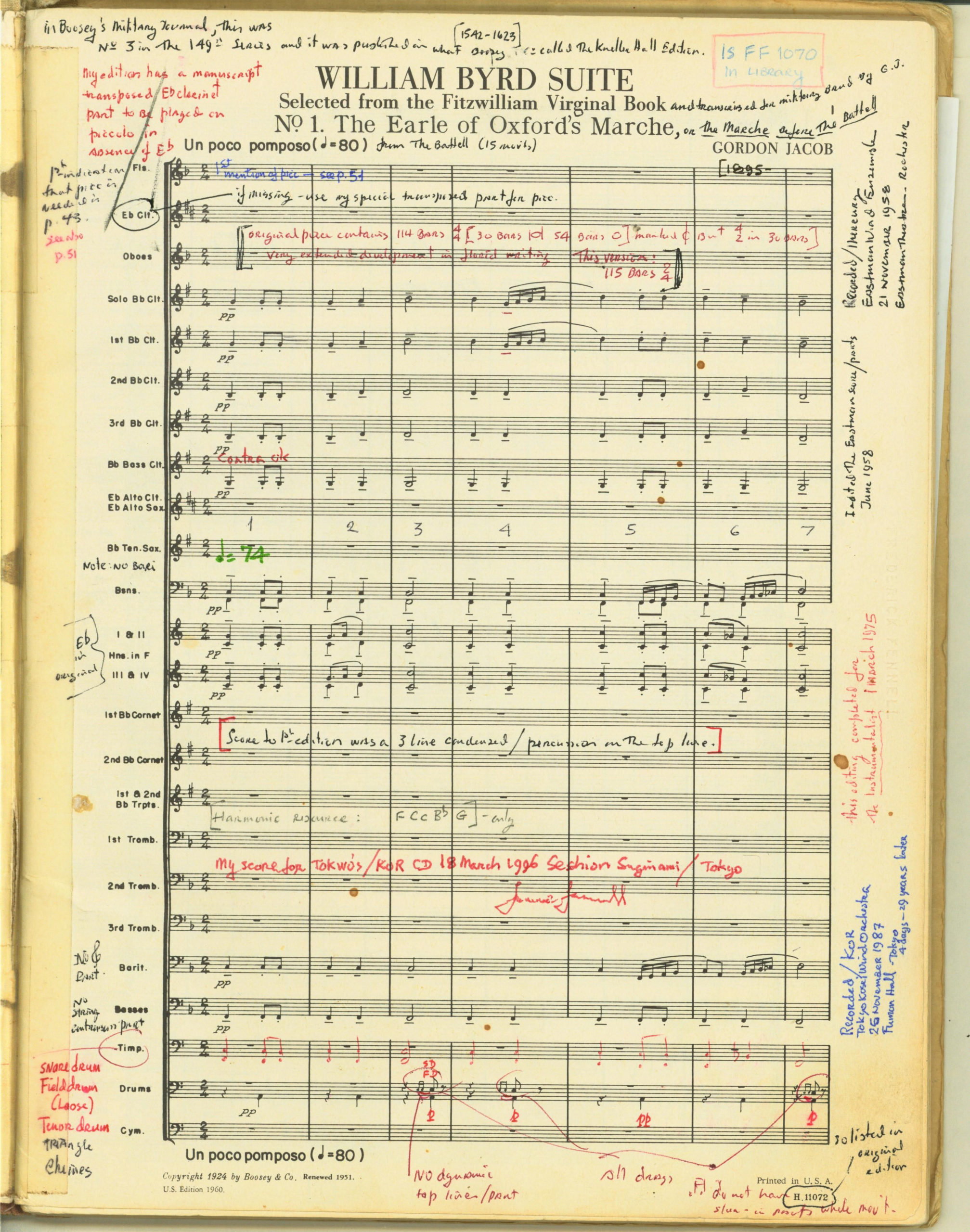

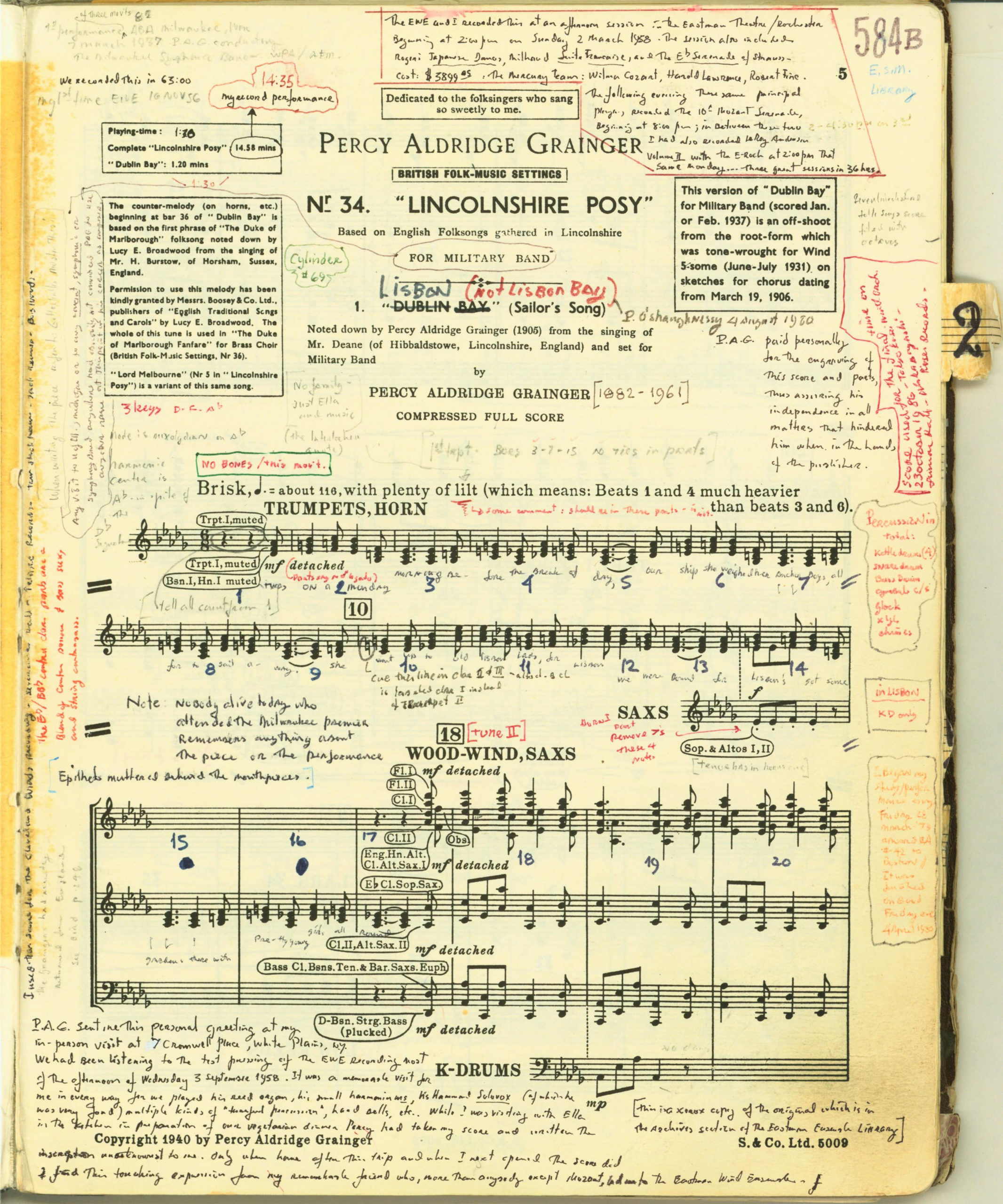

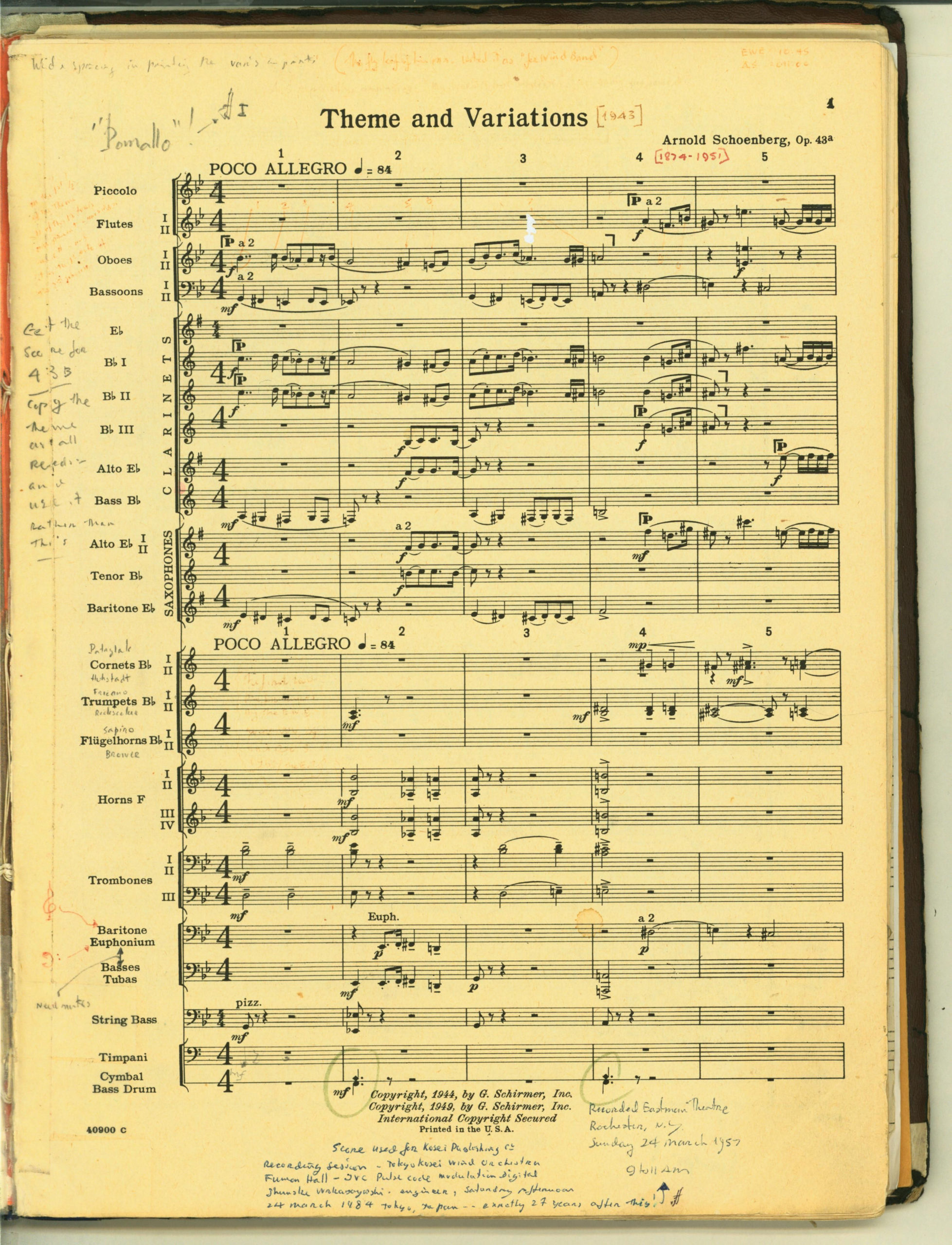

With just one exception, each of the works programmed for Carnegie Hall had previously been recorded by the EWE for Mercury Records. Further, Fennell himself had written the jacket notes for many of the Mercury albums, thereby providing learned commentary from the conductor’s standpoint. The concert’s opening work, Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Toccata Marziale (1924), was considered by Fennell to be one of the most significant pieces ever contributed to the winds or band literature, as well as one of the most difficult.[3] Next up was Gordon Jacob’s William Byrd Suite (1924), consisting of music adapted from the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book, which Fennell considered to be music ideally suited to wind performance, notwithstanding the less favorable opinion that Mr. Salzman would voice in his concert review. Next came Percy Aldridge Grainger’s Lincolnshire Posy (1905 and 1939), based on folk songs collected by Grainger, and one of Fennell’s own career favorites, which he considered to be Grainger’s best work for winds. The first half was rounded out with the Suite from the ballet Pineapple Poll by Sir Arthur Sullivan. Following the intermission, the programming of three contemporary works—Stravinsky’s Symphonies of Wind Instruments (1922; revised 1947); Schoenberg’s Theme and Variations, opus 43a (1938); and, Vincent Persichetti’s Symphony no. 6 (1956)—bore testimony to the Eastman Wind Ensemble’s unswerving commitment to perform new music for winds. (Indeed, since 1952 Fennell had been busy encouraging living composers to write for the modern wind ensemble.) The EWE’s 1957 recording of the Schoenberg had, in fact, been the debut recording of the Theme and Variations in its manifestation for winds. (Schoenberg had also written a transcription for orchestra.) The concert concluded with three marches, acknowledging the vast march repertory—field marches and concert marches alike—that has been an integral component of the band and winds literature

The concert was a huge draw for young people; approximately half of the capacity audience was comprised of teen-agers who were members of high school bands from the Greater New York City area and still further beyond. In addition, students from the Eastman School of Music travelled by bus to attend the concert and to support their colleagues. Frederick Fennell was the guest of honor at a pre-concert reception at the Barbizon Plaza Hotel that was attended by some 250 U of R alumni who were resident in the Greater NYC area. The EWE members were fêted at a post-reception, and Fennell himself hosted the high school band directors who had accompanied their students to the concert.[4] The Rochester press reported afterwards that ardent student interest in the EWE’s performance had prompted some teachers to opine that “soon there will be no more school bands, they will be ‘wind ensembles’.” And strangely, the Salzman review failed to mention that composer Vincent Persichetti had attended the concert, and had received an ovation from the audience. [5] The most succinct assessment of the concert was very likely Fennell’s own, which he recorded in his 1961 daybook with simply the two words “Smash success”.[6]

Success it had been, but for Fennell himself, there would be no resting on laurels following the EWE’s Carnegie Hall engagement. On the following Monday and Tuesday he conducted recording sessions with the Eastman-Rochester “Pops” Orchestra for Mercury Records.[7] On Friday, November 24th, exactly one week after the Carnegie Hall concert, he departed for Europe with the Eastman Philharmonia as the associate conductor for the orchestra’s landmark tour. Unbeknownst to anyone at this time (including Fennell himself), the 1961-62 academic year would mark Frederick Fennell’s valedictory season as director of the Eastman Wind Ensemble.[8] In nine years he had molded a new ensemble, fashioning it after a concept of a new medium of musical performance, and leading it on an amazing trajectory to critical acclaim and national renown.

In the decades since then, the EWE has made two more appearances at Carnegie Hall: under Donald Hunsberger’s direction on March 22nd, 1987, marking the penultimate concert of a tour of the East Coast and Canada with featured guest soloist Wynton Marsalis on trumpet, a tour promoting the repertory that would appear on the EWE’s CBS Masterworks release Carnaval; and under Mark Davis Scatterday’s direction on February 26th, 2005, as part of “A Celebration of the Contemporary Wind Band” presented by the 2005 CBDNA national conference. That program featured works by Robert Sierra, David Maslanka, Jeff Tyzik, and Karel Husa (significantly, Dr. Husa was in attendance). These two later performances reflected newly emerging facets of the EWE’s mission and repertory, signalling the ensemble’s endless capacity for innovation. For us now in 2022-23, when we are about to observe the 70th anniversary of the EWE’s founding, we can look back on this history with pride. In the Eastman Wind Ensemble’s success and achievement, the Eastman School of Music had once again distinguished itself as a standard-bearer for excellence in performance and in musical innovation.

1962: The Eastman Philharmonia

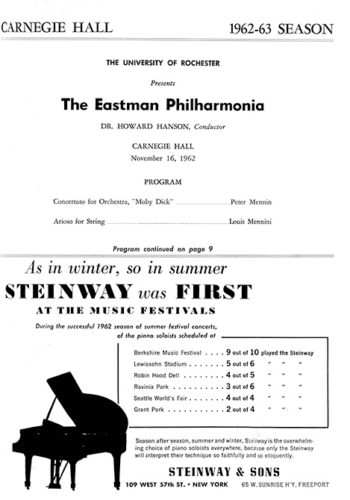

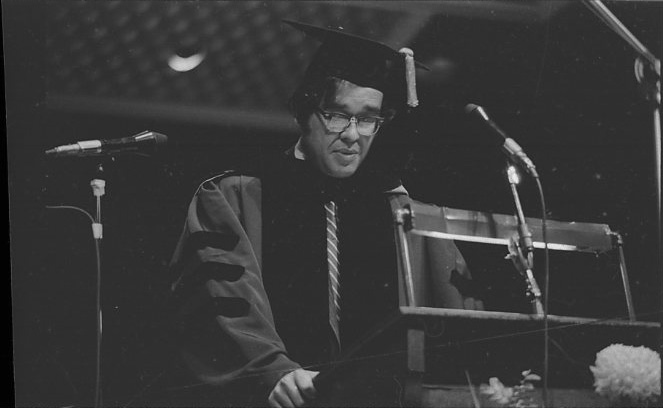

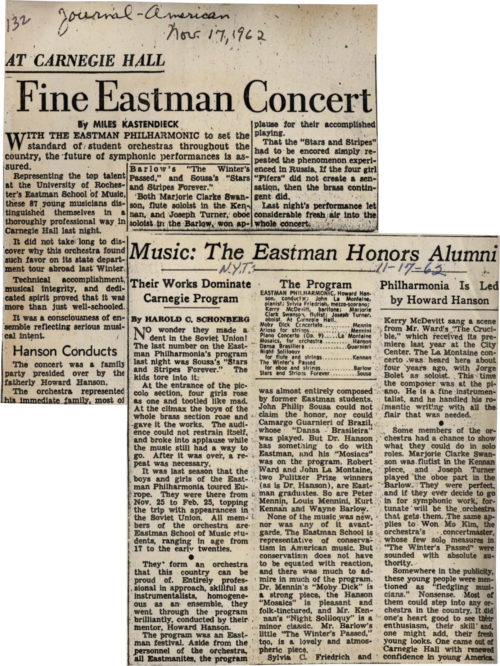

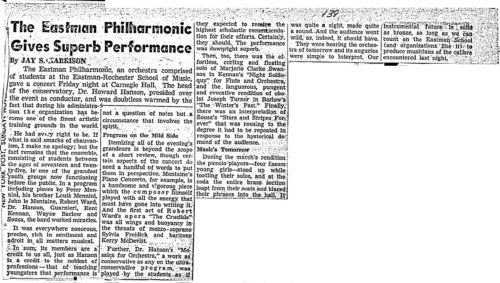

Almost exactly one year after the Eastman Wind Ensemble’s debut at Carnegie Hall, the Eastman Philharmonia made its own debut there on the evening of Friday, November 16th, 1962. The Eastman Philharmonia was then in its fifth season, having been founded by Howard Hanson at the beginning of the 1958-59 academic year. The orchestra had scored one success after another right from the outset; in the first season Hanson had taken the orchestra on run-outs to Atlantic City and to Buffalo, and then in the spring of 1961, the orchestra had performed in Washington, D.C.. In the winter of 1961-62, the orchestra had undertaken its landmark European tour. Before Hanson retired, he would take the Eastman Philharmonia out of town once more, this time to perform at the 1964 New York World’s Fair, but arguably, it was the Carnegie Hall debut that trumped all of the other domestic guest appearances. The concert at Carnegie Hall was a direct legacy of the Eastman Philharmonia’s 1961-62 tour, one of several initiatives that celebrated and capitalized on the renown enjoyed by the orchestra in the aftermath of its international undertaking.[9] It should be noted that the orchestra’s personnel composition was no longer identical to that of the Philharmonia on tour in 1961-62, for a new academic year had begun, and numerous members of the orchestra had graduated the previous spring.

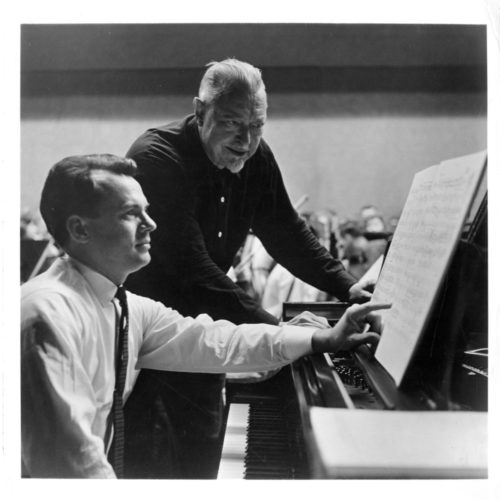

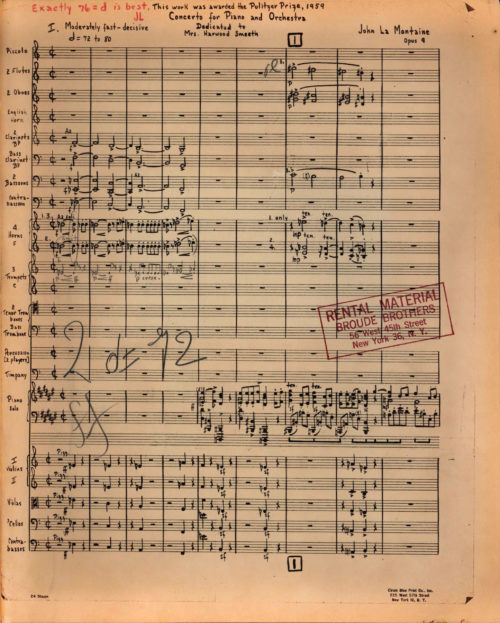

For the Carnegie Hall concert Hanson had chosen music almost entirely by Eastman School alumni composers. Two of the composers—Robert Ward and John La Montaine—were represented by works which had been recognized with the Pulitzer Prize. The most substantive work on the program, from the standpoint of duration, was Mr. La Montaine’s Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, opus 9. The work had been commissioned by the American Music Center for the National Symphony Orchestra under a grant from the Ford Foundation. This Concerto ultimately proved to be the composer’s first of four concertos for piano and orchestra. Mr. La Montaine was a gifted pianist in his own right, and in 1965 he would return to Eastman as soloist in this Concerto at the Eastman School’s annual Festival of American Music. When Mr. La Montaine had won the Pulitzer Prize for the Concerto in 1959, he had been the Eastman School’s second composer-graduate to have been so honored. For the record, the Eastman School’s Pulitzer Prize-winning composer-graduates have been the following:

Gail Kubick, 1952 (BM ’34)

John La Montaine, 1959 (BM ’42)

Robert Ward, 1962 (BM ’39)

Dominic Argento, 1975 (PhD ‘57)

George Walker, 1996 (DMA ’56)

Kevin Puts, 2012 (BM ’94, DMA ’99)

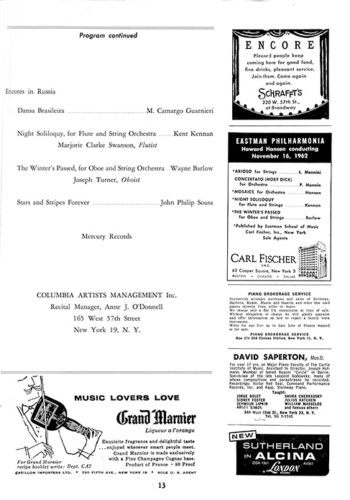

► 1961 November 16 Eastman Philharmonia at Carnegie Hall

Among the other works on the program, Howard Hanson’s Mosaics was still a new work, having been composed in 1958 on a commission by the Cleveland Orchestra. In the first few years the work had been performed by numerous orchestras around the country. That Hanson had used this opportunity at Carnegie Hall to promote one of his own works was not unusual, for he had routinely conducted his own music both at Eastman and on the road. (Indeed, the repertory for the landmark 1961-62 tour had included his own Symphony no. 2 (“Romantic”) and also his Elegy in Memory of Serge Koussevitzky.) Robert Ward’s opera The Crucible, represented on this concert program by way of excerpts, had won the composer a Pulitzer Prize in the same year of its premiere, and had established itself at once in the American operatic repertory. For the record, The Crucible has been produced at Eastman three times in its entirety (1963, 1973, 1986). It was significant that Hanson included at this concert four encores that he had conducted in the U.S.S.R during the Eastman Philharmonia tour. After the tour he had proudly recounted, both on the air and in print, how Russian audiences had enthusiastically received John Philip Sousa’s The Stars and Stripes Forever, clapping in unison and loudly shouting “Amerikanskii marsh (American march)!!” by way of requesting one more rendition. Hanson would surely have approved when that same march was named the U.S.A.’s National March in 1987 by an act of Congress and with President Reagan’s signature.[10]

In the years since 1962, the Eastman Philharmonia has been back to New York City on several occasions, including three more engagements at Carnegie Hall (1972, 1983, 1990), as well as concerts at Alice Tully Hall. The 1962 concert may be regarded as special in more than one respect—not only for having been the orchestra’s first time in that renowned venue, but also for having confirmed the orchestra’s newly-won status as an ensemble of world-class stature.

_____________________________________________________________________________

[1] A photograph of Fennell taken at the first rehearsal was published in Roger E. Rickson’s book Ffortissimo!: a bio-discography of Frederick Fennell (Ludwig Music Publishing, 1993).

[2] “Carnegie program readied.” Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, October 29th, 1961. Rochester Scrapbook October-November-December 1961, page 5. Sibley Music Library.

[3] Fennell made the following annotation on his copy of the score: “4:20 of the most difficult wind band music in the repertory! !”. He would later publish an analysis of the work in the Basic Band Repertory series in The Instrumentalist, August, 1976. In that article Fennell recounts having met RVW at Cornell University, seeking the composer out specifically to discuss his Folk Song Suite and Toccata Marziale, his first and second works for winds.

[4] “Wind group to leave for Albany.” Rochester Times-Union, November 16th, 1961. Rochester Scrapbook October-November-December 1961, page 34. Sibley Music Library.

[5] “New York praises ensemble” by Harvey Southgate. Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, November 18, 1961. Rochester Scrapbook October-November-December 1961, page 35. Sibley Music Library.

[6] In his adulthood Fennell kept a daybook for each calendar year, meticulously keeping track of appointments and engagements and adding some editorial commentary along the way. He favored the yearly “Musician’s Diary” reference and appointment books, printed in England.

[7] Recording sessions for the album Frederick Fennell Conducts Cole Porter, which would feature twelve hit songs by Cole Porter in arrangements by Eastman alumnus Ray Wright, ’43, at that time working at Radio City Music Hall. Other “pops” albums that Fennell conducted for Mercury Records featured music by George Gershwin and by Leroy Anderson.

[8] The personal narrative published in Roger E. Rickson’s Ffortissimo! tells Fennell’s—and the Eastman Wind Ensemble’s—story of the years 1952-62 in some detail.

[9] One other project was the orchestra’s Mercury Records recording, The Eastman Philharmonia, Musical Diplomats, U.S.A.

[10] Public Law 186, 100th Congress, 1st session (December 11, 1987).