Online exhibit from the Ruth T. Watanabe Special Collections; curated by Gail E. Lowther.

Karel Husa’s masterful Music for Prague 1968 is widely regarded as a staple of wind band repertoire. Since its premiere in January 1969, performers, reviewers, and audiences alike have embraced the poignancy of the work’s message of the brutality of war and the universal longing for freedom.

In November 2016, the Karel Husa Archive—an extensive collection of the composer’s manuscripts and sketches, performance scores, recordings, and papers—arrived at Sibley Music Library, having been transferred at the composer’s request from its first home at Ithaca College. Music for Prague 1968, along with many of Husa’s other masterpieces, is intimately preserved in the Archive in sketches and scores, recordings, newspaper reviews, photographs, letters, and innumerable documents, many of which testify of the work’s powerful and lasting impact.

On Display

The story behind Music for Prague 1968—and Karel Husa’s inspirations for the work—are well known. For the composer, the composition was a very personal response to the overnight invasion of Czechoslovakia, Husa’s home country, on August 20–21, 1968, by Warsaw Pact forces aiming to end the liberal regime of Alexander Dubček and suppress the country’s movements toward democracy. As Husa listened to radio reports of the invasion from his summer cottage on New York’s Cayuga Lake, the composer was inspired to memorialize the event—and his beloved homeland—through his music. The previous May, Husa had accepted a commission from Dr. Kenneth Snapp and the Ithaca College Concert Band, and so the composer fueled his anger and disbelief about the invasion into the piece. Reflecting on this work, Dr. Mark Davis Scatterday, Professor of Conducting and Ensembles and close friend of Karel Husa, observed, “The emotional impact, historical significance, musical stature and personal dignity embodied in [Husa’s] music provides a unique opportunity for ensembles, conductors and audiences to perhaps experience some of the commitment to the dignity and freedom of mankind that Karel Husa must have known when he wrote Music for Prague 1968 and re-lives every day of his life.”[1]

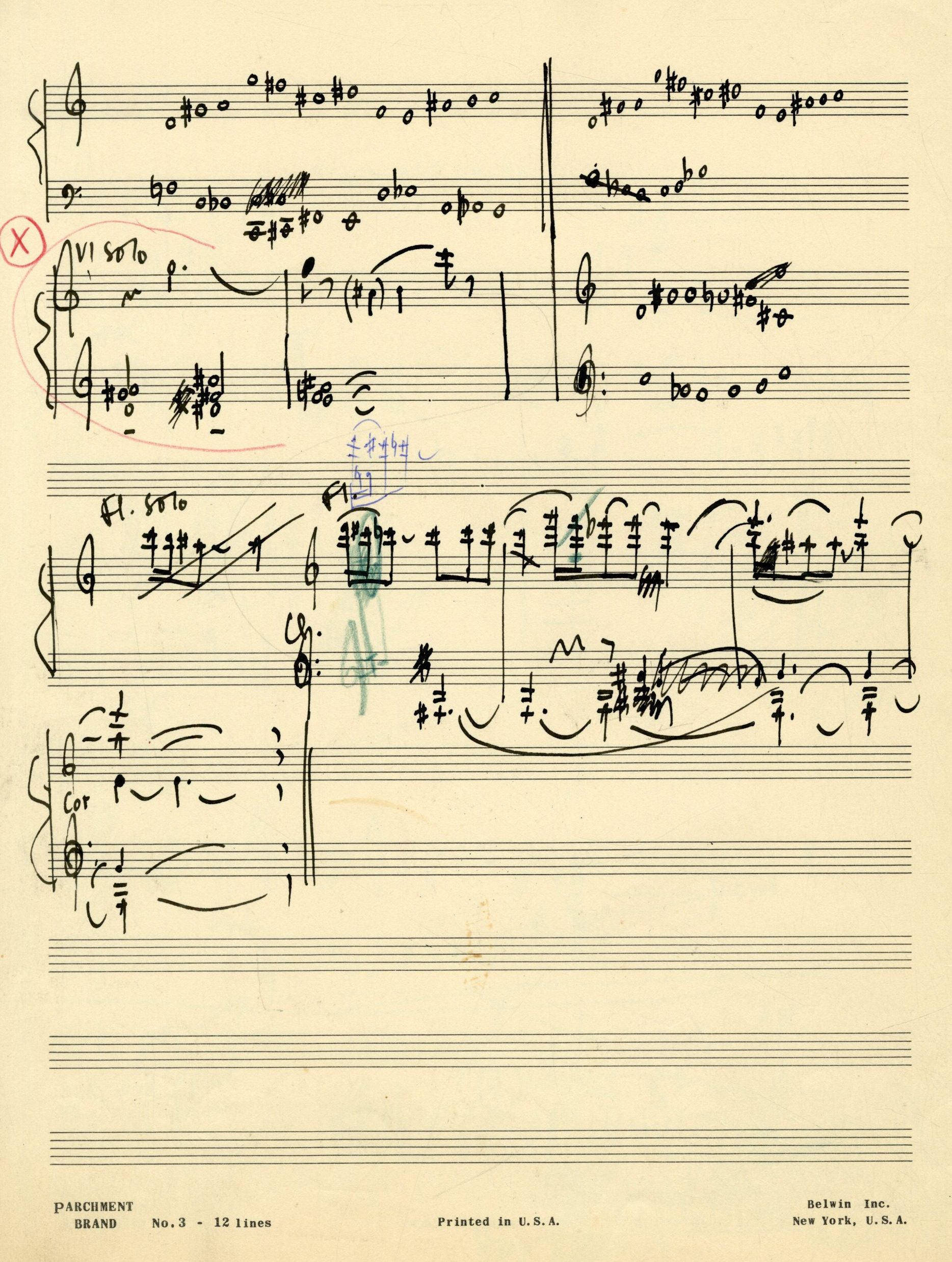

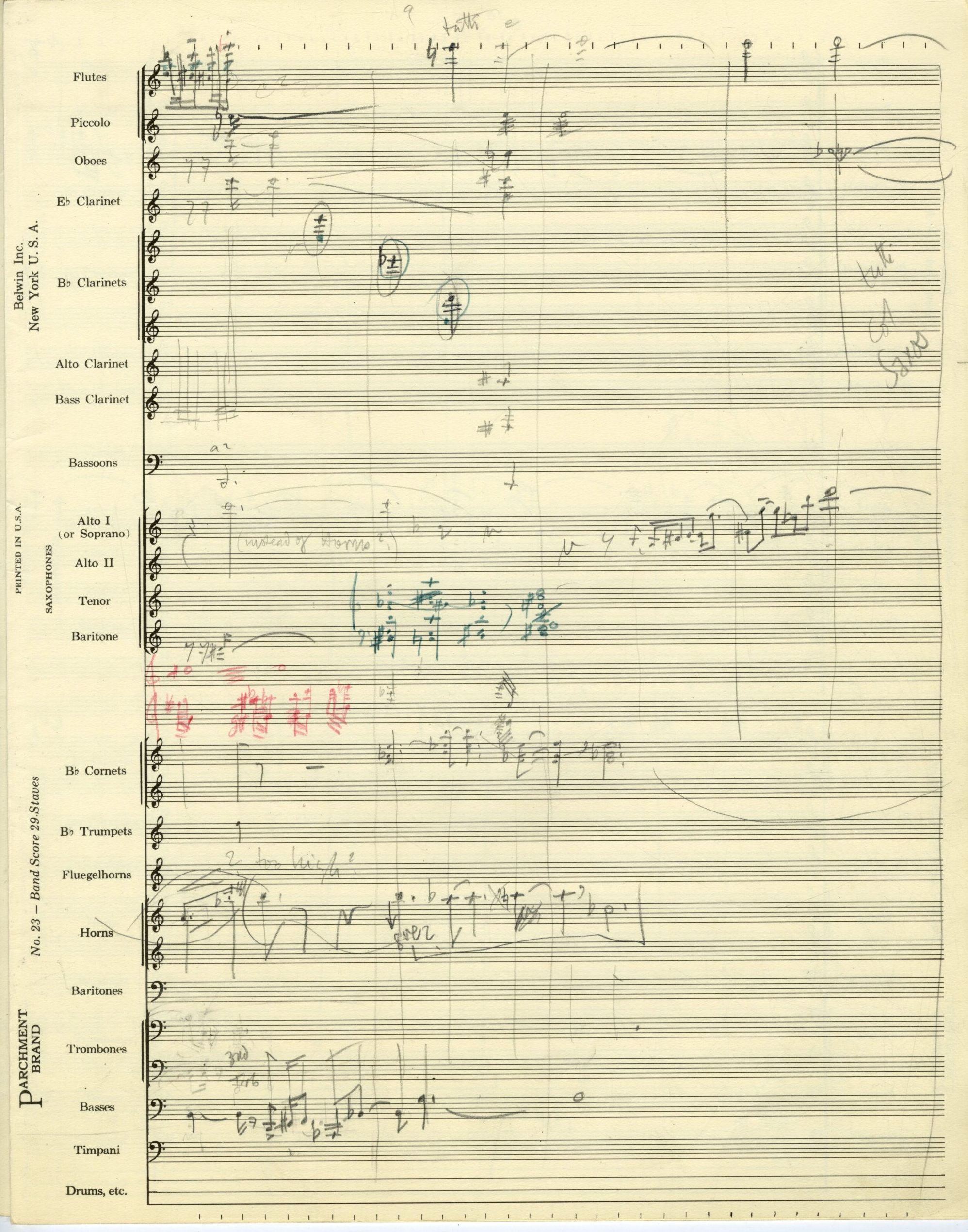

Several stages of sketches for Music for Prague 1968 are preserved in the Archive, giving us a snapshot into the work’s genesis and development. One set of sketches—11 pages in total and distinguished by the use of heavy black ink—appears to bear the earliest traces of what would eventually become Music for Prague 1968. In his analysis of the sketches, Dr. Zachary Cairns (‘10E, PhD) identifies a few pages in the middle of the set, which show Husa working with the twelve-tone row that would eventually be used in the opening of the first movement.[2] On the first page shown here, we see the row (Row A) in prime form (staff 1) and its sum-7 inversion (staff 2). Underneath the row—marked “X” in red pencil—is a rough outline for a violin solo with three dissonant chords derived from Row A. (Husa later described this sequence of three chords as a “chorale-like motif” that appears several times throughout Music for Prague 1968 as a unifying element.) In the work’s later form for concert band, the violin solo would be replaced by piccolo, and the three chords would be taken by flute, clarinet, and horn as measures 3-4 in the band score.

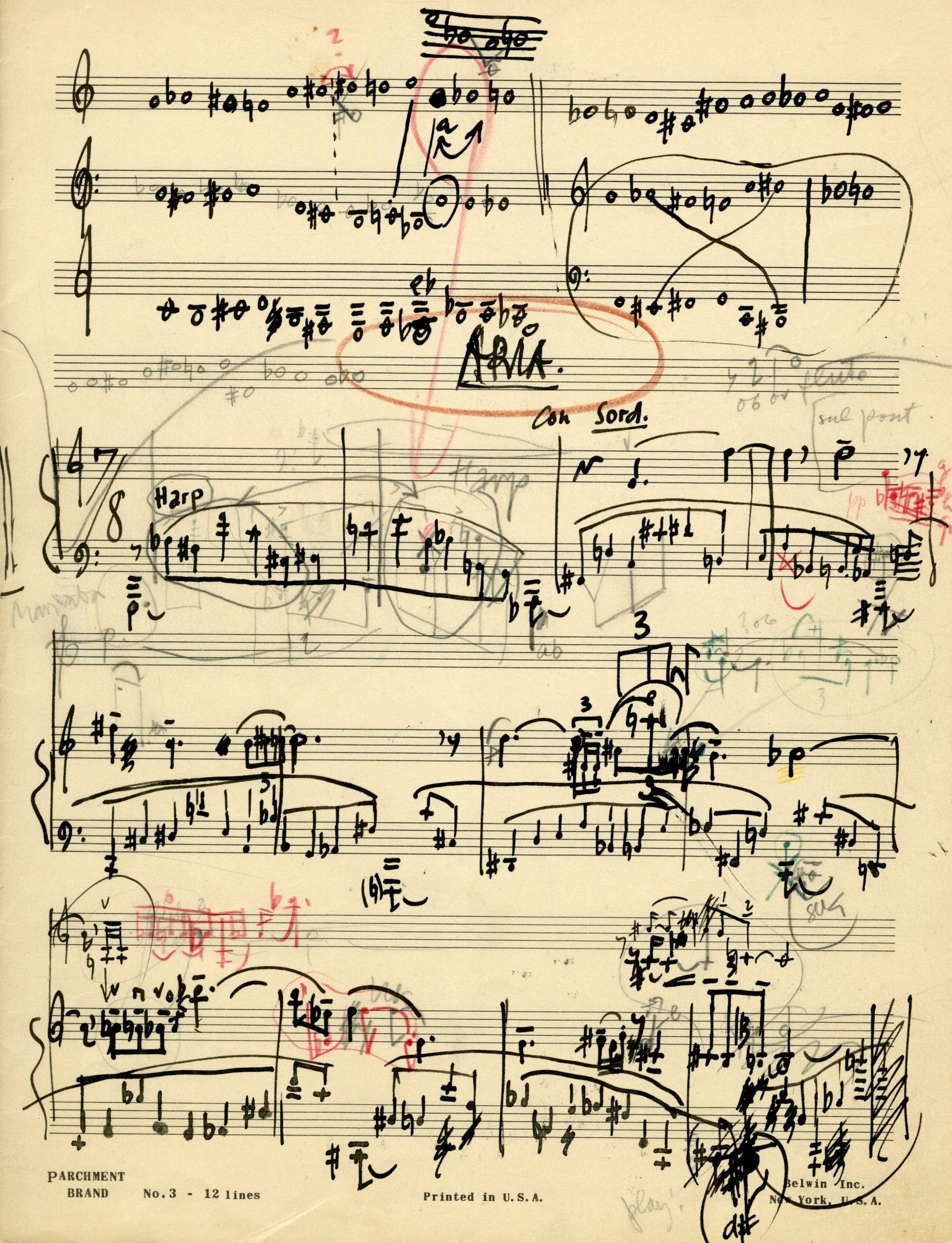

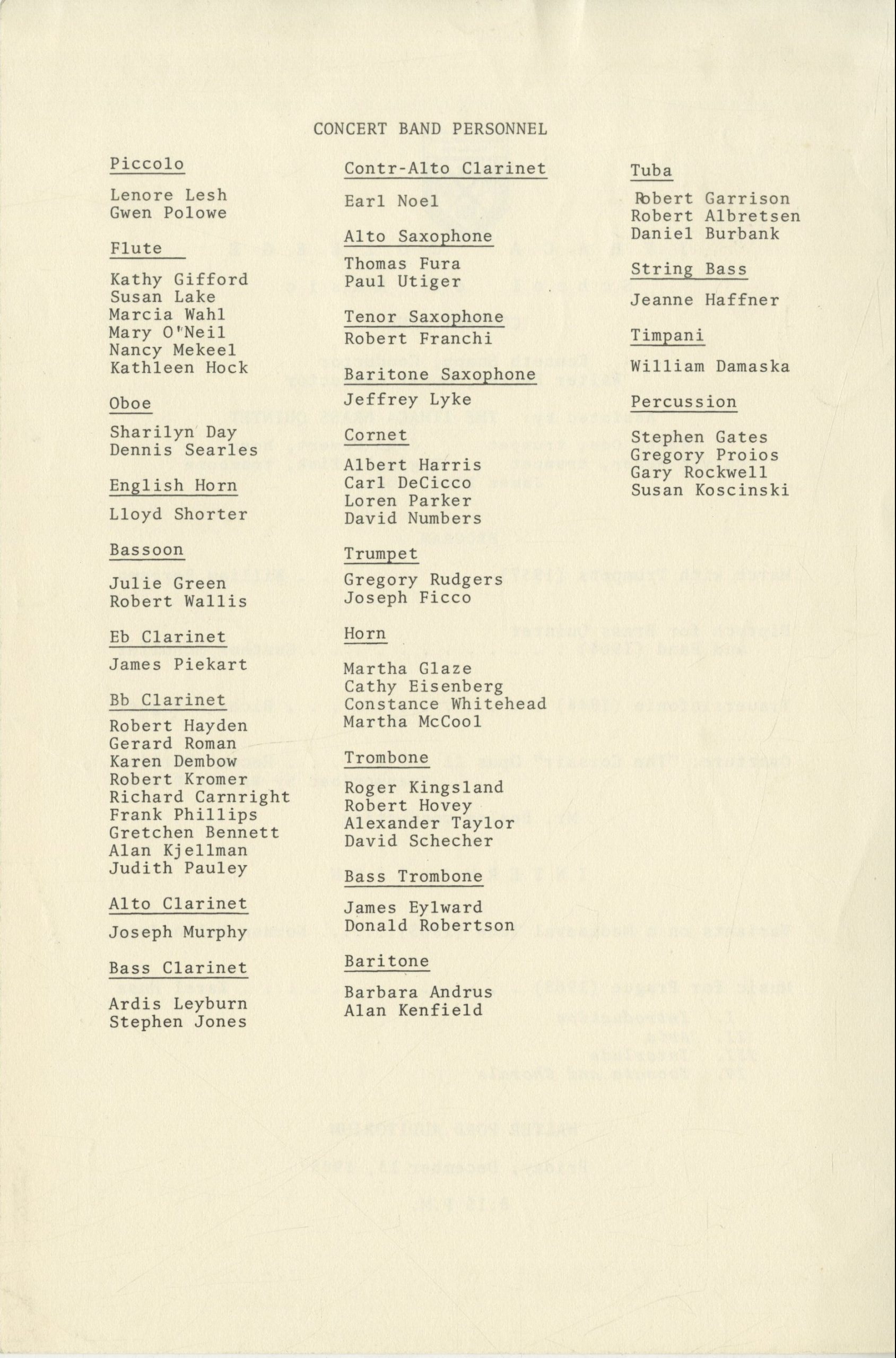

Another page from this set of sketches is labeled “Aria”—the title of the second movement of Music for Prague 1968. Here we see the second primary tone row used in the piece (Row B) written out across the topmost staves, followed by several musical ideas built from fragments of the row. The heavily marked and revised sketches in this folio bear some structural similarities to the opening of the final “Aria”: the pitches for the harp accompaniment in the sketch were repurposed for vibraphone and marimba, and the solo (marked “con sord.” in the sketch) became the tutti saxophone melody.

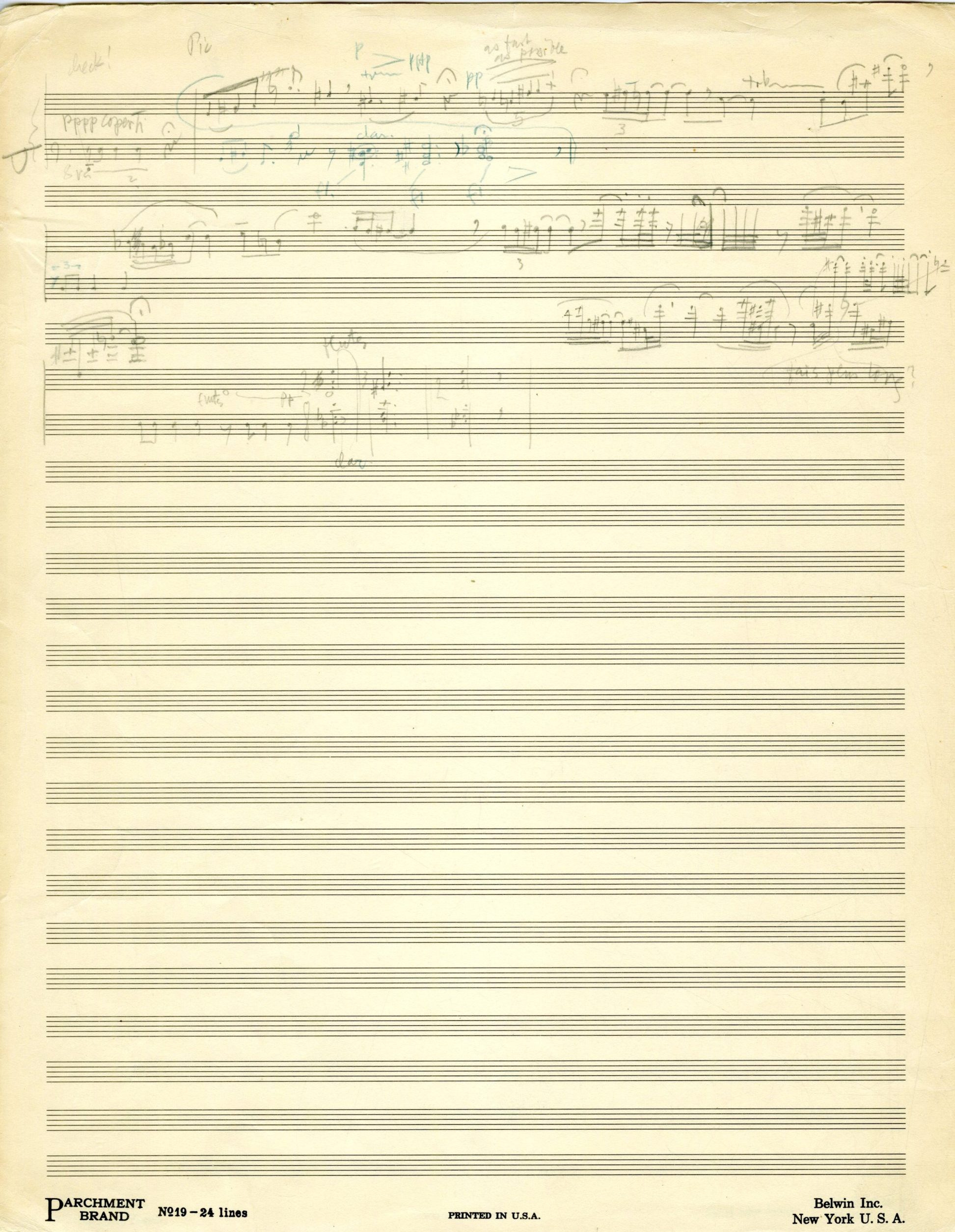

Husa’s heavy ink sketches are supplemented with several pages of pencil sketches. One leaf of manuscript paper bears the unmistakable outlines of the opening piccolo solo, now expanded with figurations evoking birdsong; the opening measures can be seen in blue pencil in the second staff, and the line continues in grey pencil on the staff above. Supporting the solo is (in blue pencil) the unifying “chorale-like motif”—those three, dissonant chords derived from Row A that first appeared in the ink sketches. Significantly, this whole section is introduced by a haunting solo timpani intoning the first four, repeated notes of the Hussite war song “Ye Warriors of God.”

In a foreword later written for the published score, Husa identifies the significance of these key motifs:

Three main ideas bind the composition together. The first and most important is an old Hussite war song from the 15th century, “Ye Warriors of God and His Law,” a symbol of resistance and hope for hundreds of years, whenever fate lay heavy on the Czech nation. It has been utilized also by many Czech composers, including Smetana in My Country. The beginning of this religious song is announced very softly in the first movement by the timpani and continues in a strong unison (Chorale). The song is never used in its entirety.

The second idea is the sound of bells throughout; Prague, named also the City of “Hundreds of Towers,” has used its magnificently sounding church bells as calls of distress as well as of victory.

The last idea is a motif of three chords first appearing very softly under the piccolo solo at the beginning of the piece, in flutes, clarinets, and horns. Later it reappears at extremely strong dynamic levels, for example, in the middle of the Aria.

Different techniques of composing as well as orchestrating have been used in Music for Prague 1968 and some new sounds explored, such as the percussion section in the Interlude, the ending of the work, etc. Much symbolism also appears: in addition to the distress calls in the first movement (Fanfares), the unbroken hope of the Hussite song, sound of bells, or the tragedy (Aria), there is also the bird call at the beginning (piccolo solo), symbol of the liberty which the City of Prague has seen only for moments during its thousand years of existence.

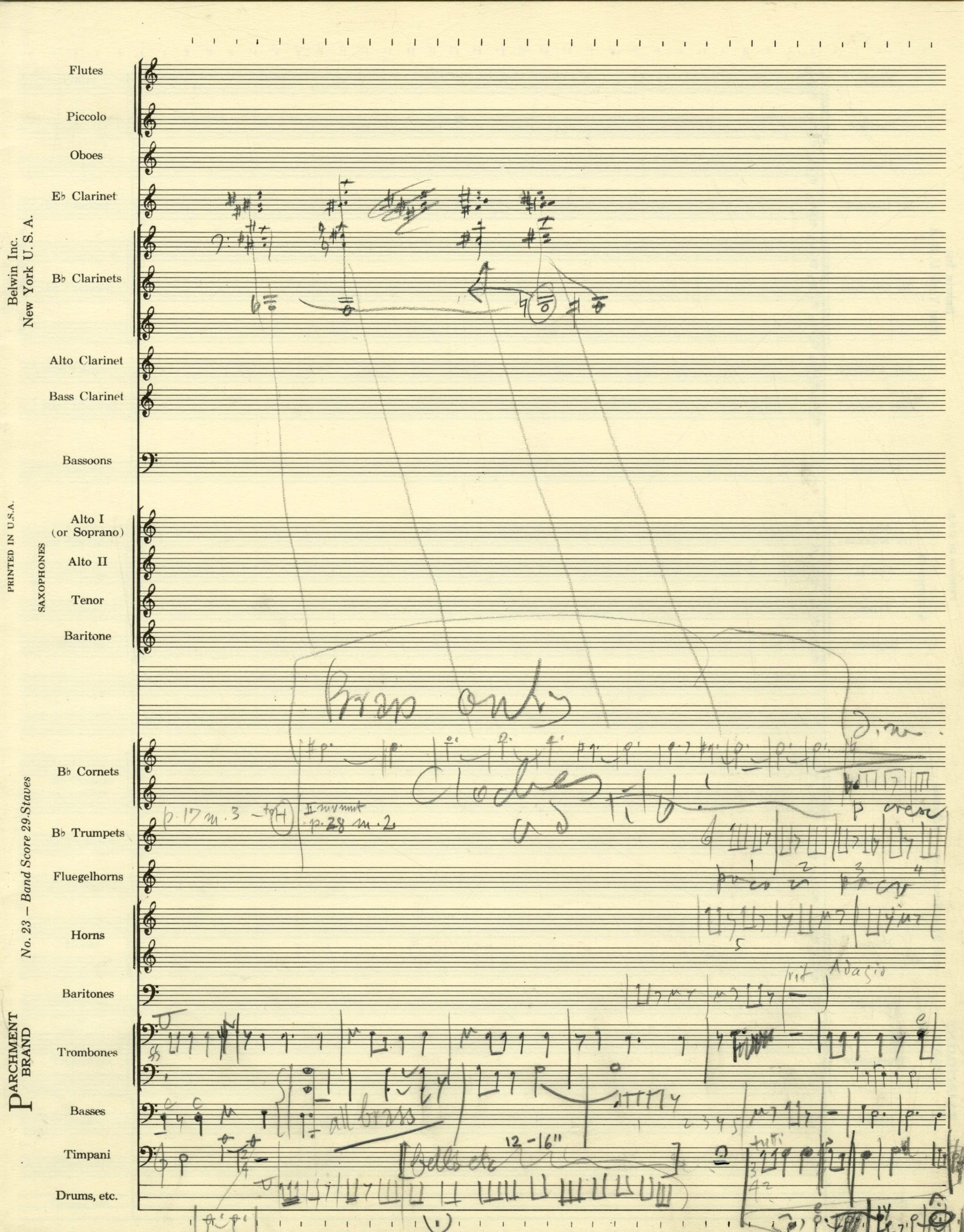

Joining these partial sketches is a full but rough score of the complete composition in pencil, with emendations or revisions and additional markings added in colored pencil. The two pages shown here—the first from the second movement (Aria) at rehearsal letter K and the second from the conclusion of the fourth movement (Toccata and Chorale)—are characteristic of most this draft. Though the work’s overall construction and main musical ideas appear to have been set by the time Husa produced this score, the pages bear traces of many erasures and revisions, added inner voices, and adjusted instrumentation.

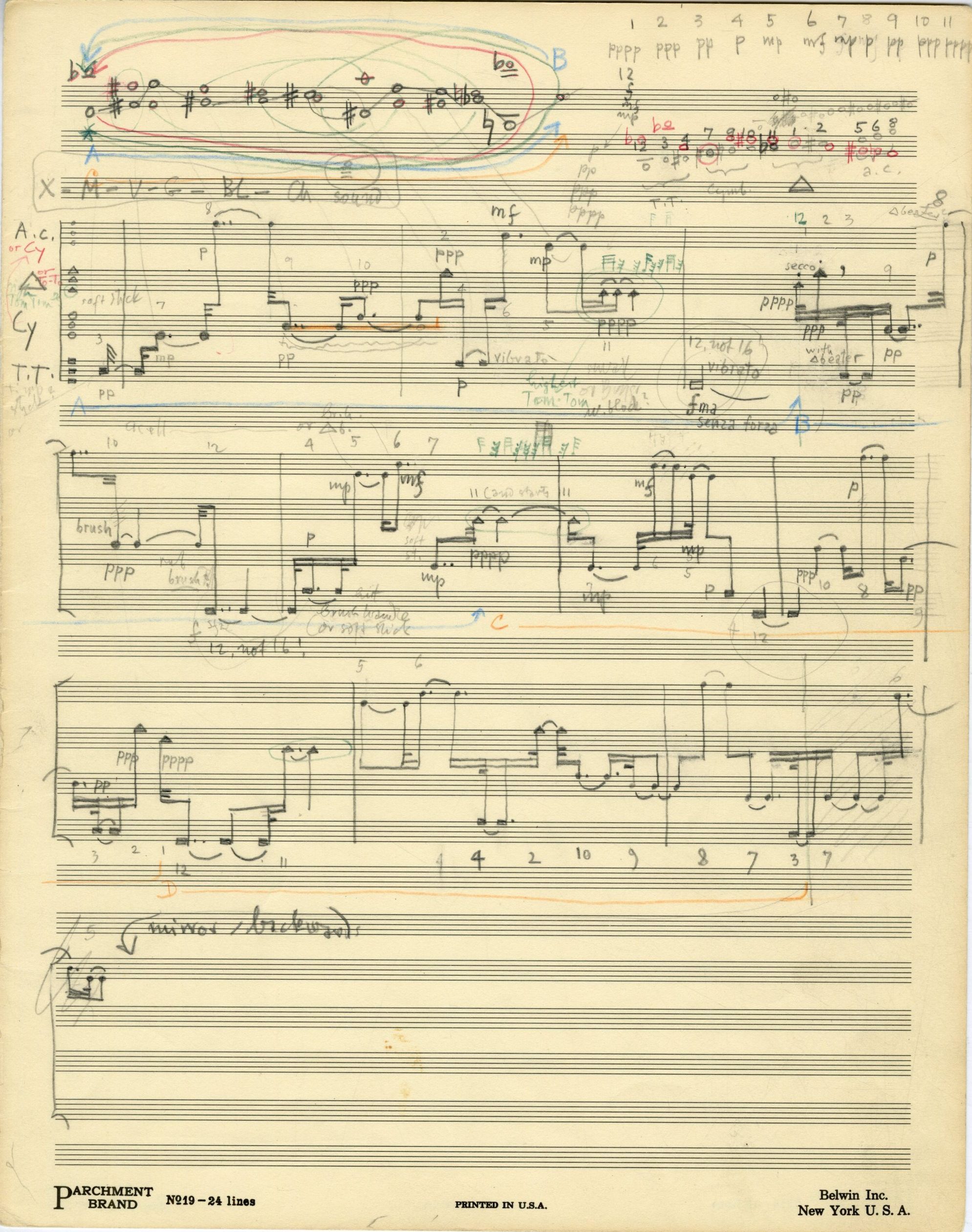

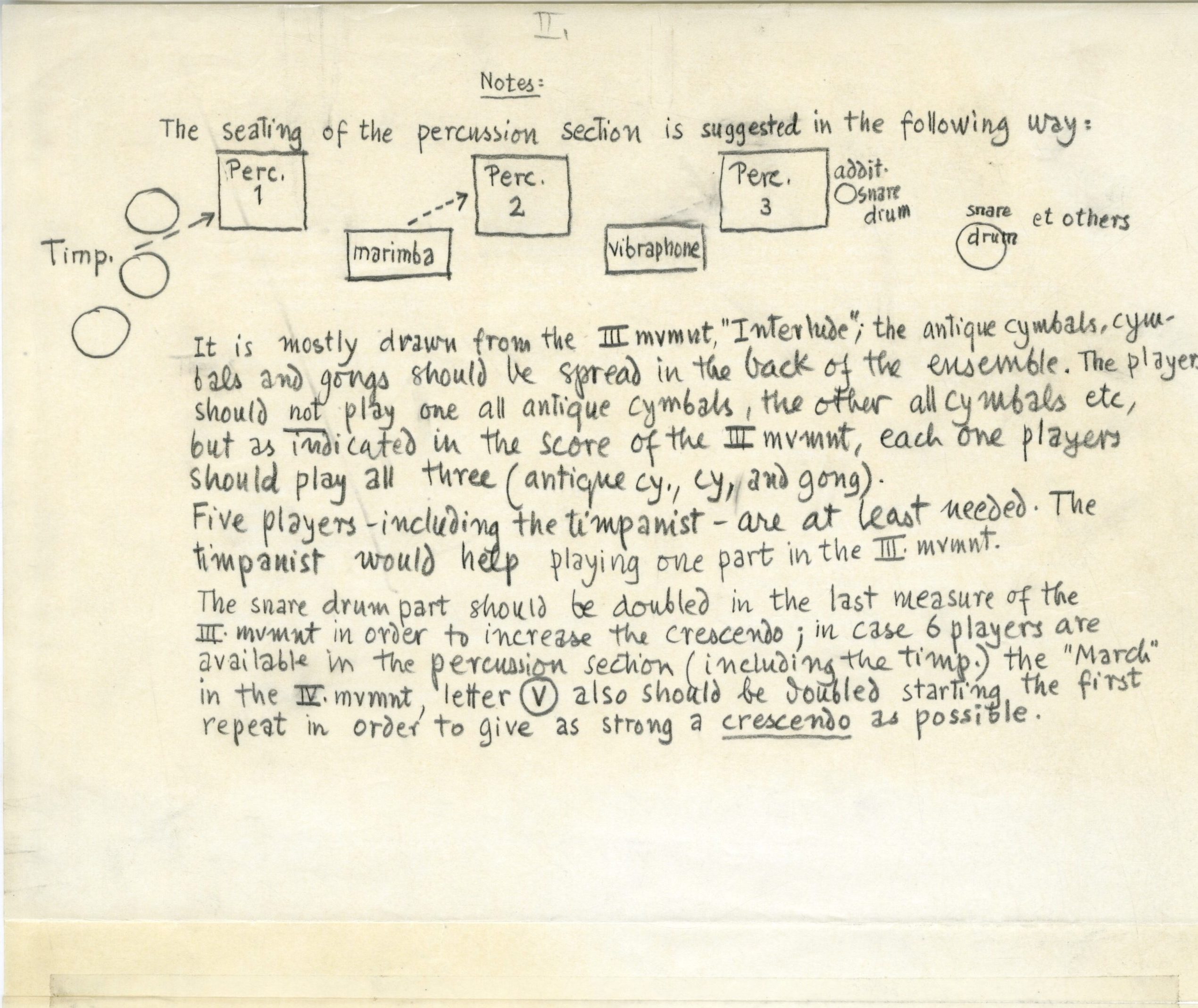

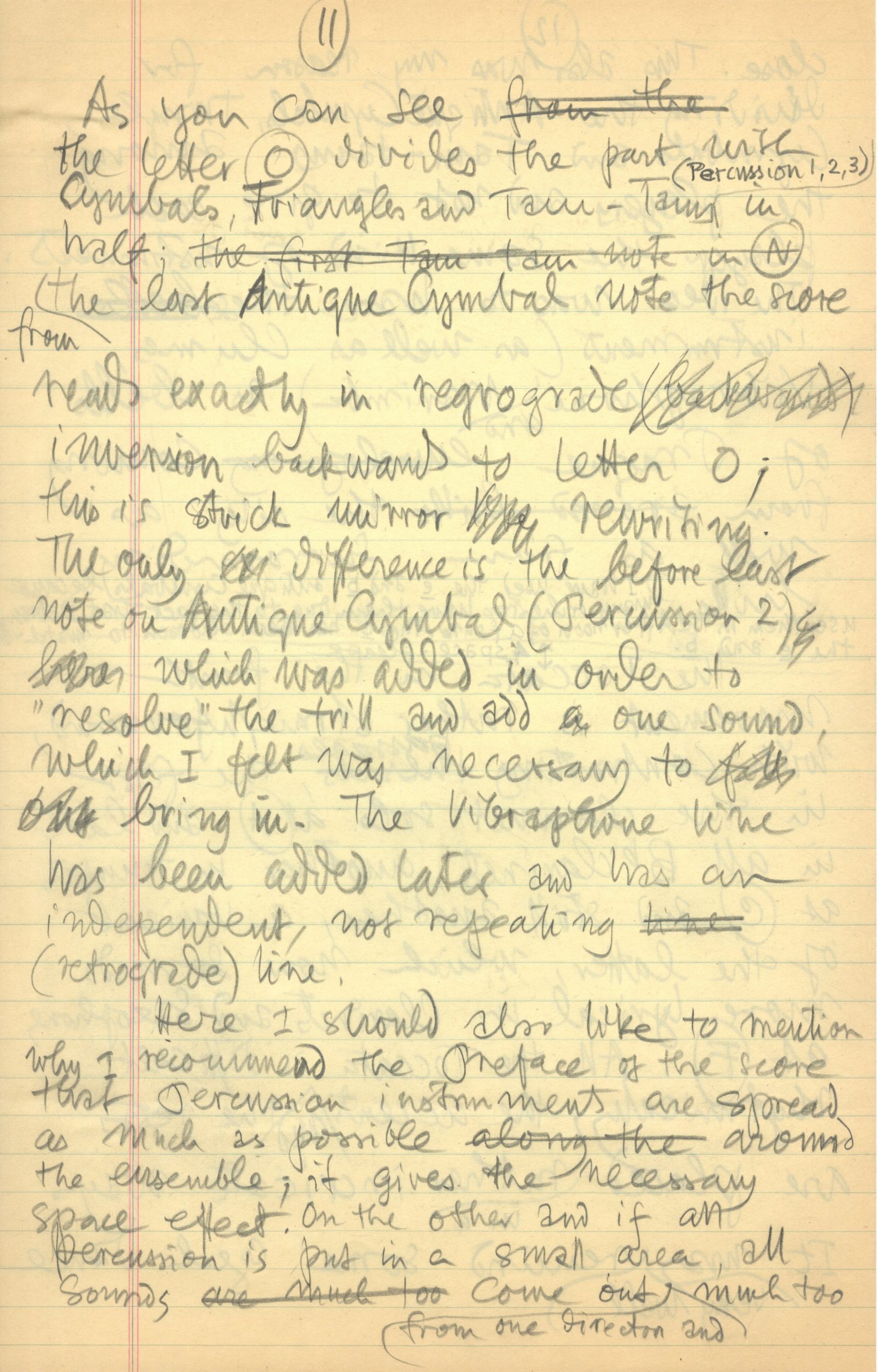

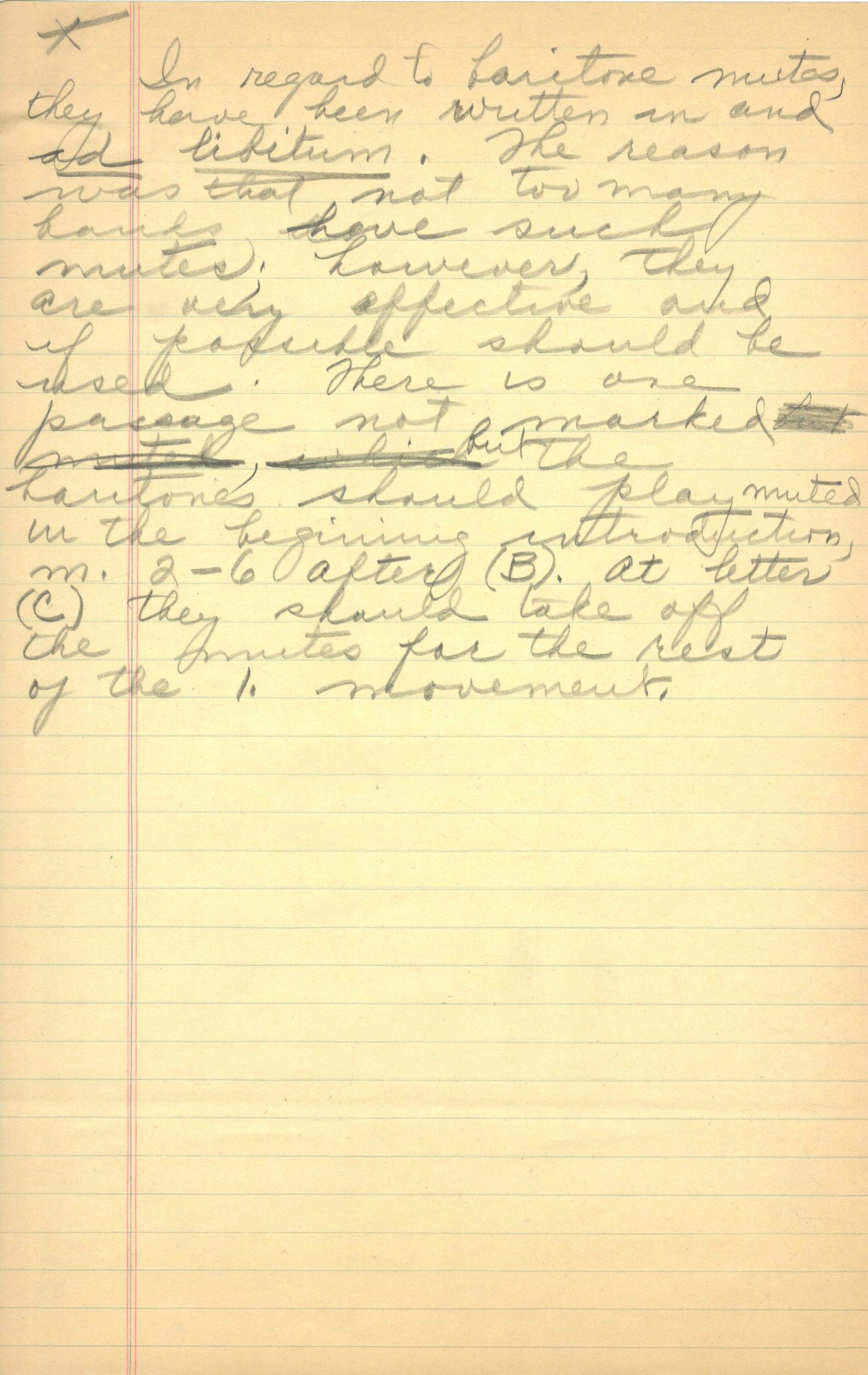

Within this draft, the pages for the third movement (Interlude) stand out as they feature visibly heavier pencil strokes and comparatively few revisions to the musical content, which suggests that this is a fairly late sketch, produced when Husa had largely finalized his ideas for the movement. The staves in the middle of the page outline the three percussion parts—cymbals, triangles, and tam-tam—that form the core of the movement (see Husa’s note on the percussion seating from the final pencil score). The composer’s continued use of serial techniques is also evident: the upper right corner of this page from the draft (rehearsal letters N through O) contains a key to Husa’s serialization of dynamics. (The pitches or timbre and rhythmic durations in the movement are also serialized between rehearsal letters N and P.) The handwritten note at the end of this page (“mirror/backwards”) reveals the movement’s formal design: Husa uses strict mirror writing that divides the movement at rehearsal letter O. Husa’s vision for this percussion interlude is supplemented with a performance note—which Husa wrote in pencil above the foreword in the final manuscript score—that describes the composer’s suggested layout for the percussion section and recommended distribution of parts.

Music for Prague 1968 was officially premiered at the Eastern Division MENC Conference in Washington, DC, on January 31, 1969, by the Ithaca College Concert Band with Dr. Kenneth Snapp, conducting. A recording of the premiere (on LP) is preserved in the Archive along with nearly 140 other recordings of the piece by professional, collegiate, and high school wind bands and orchestras.

A month before the official premiere, the IC Concert Band gave the first “unofficial” performance of Husa’s work at their winter concert on December 13, 1968, in Ithaca College’s Walter Ford Auditorium. In his review of the performance for the Ithaca Journal, George E. Clarkson reflects on the lasting impact of Husa’s masterpiece:

The major work of the evening was [one] commissioned for the Concert Band composed by Karel Husa: “Music for Prague.” Very interesting techniques in composing as well as orchestrating were used as drum beats began and the theme from an only Hussite song (really a symbol of resistance) moved from one flute and piccolo to the other. The 15th century song was also used by Smetana, but as woven by Karel Husa, the theme spoke of all the passion of the Czechs and their deep longing for freedom. The song was also a mark of unity, appearing at the outset (though never in its entirety) and then coming back with stirring strength in the final Chorale. Even in the tragic “Aria” section there was a strange majesty. The color of Prague with its “hundreds of towers” came through with the persistent ringing as though one could not leave the city. One left after this last work with a strong feeling that music as great as this should not be written about: one should only listen, and be deeply moved.

Music for Prague 1968 received immediate acclaim, and within months of its premiere at the MENC division conference, the work had already received dozens of performances by college and university bands across the US. One particular champion of the work was Dr. William Revelli, long-time director of bands at the University of Michigan and a close colleague of Karel Husa. Revelli first performed Music for Prague 1968 with his Symphony Band for the University of Michigan Bands spring concert on April 13, 1969; the response, as he later wrote to Husa, was “tremendous” and left the university campus “buzzing with the reports of this fine work.” He promptly included the piece in the repertoire for the band’s California Western Tour, during which he performed the piece another 17 times to great enthusiasm (see Revelli’s May 27, 1969, letter to Karel Husa). In his April letter, Revelli predicted that Music for Prague 1968 “will become one of the most widely accepted works of the band repertoire in time”—an accurate prophecy, realized through thousands of performances worldwide in the decades that followed. Revelli himself remained a particular champion of the piece, conducting it more than 150 times with bands in the US and Europe over the next two decades.

In 1969, while preparing the band score for publication by AMP, Husa also began adapting the music for orchestra. The composer-conductor frequently traveled abroad for guest conducting engagements in Europe, and knowing that concert bands were less common in Europe at the time, he felt that an orchestral transcription would make the piece more accessible to European ensembles. Shown here is the first page of movement 2 (Aria) from Husa’s orchestral arrangement: the composer worked from a printed reproduction of his band score (in manuscript), pasting in the parts for strings and harps and marking other adjustments in orchestration and instrumentation in colored pencil. Husa premiered the orchestral version with the Munich Philharmonic on January 31, 1970, in Munich (with the composer conducting).

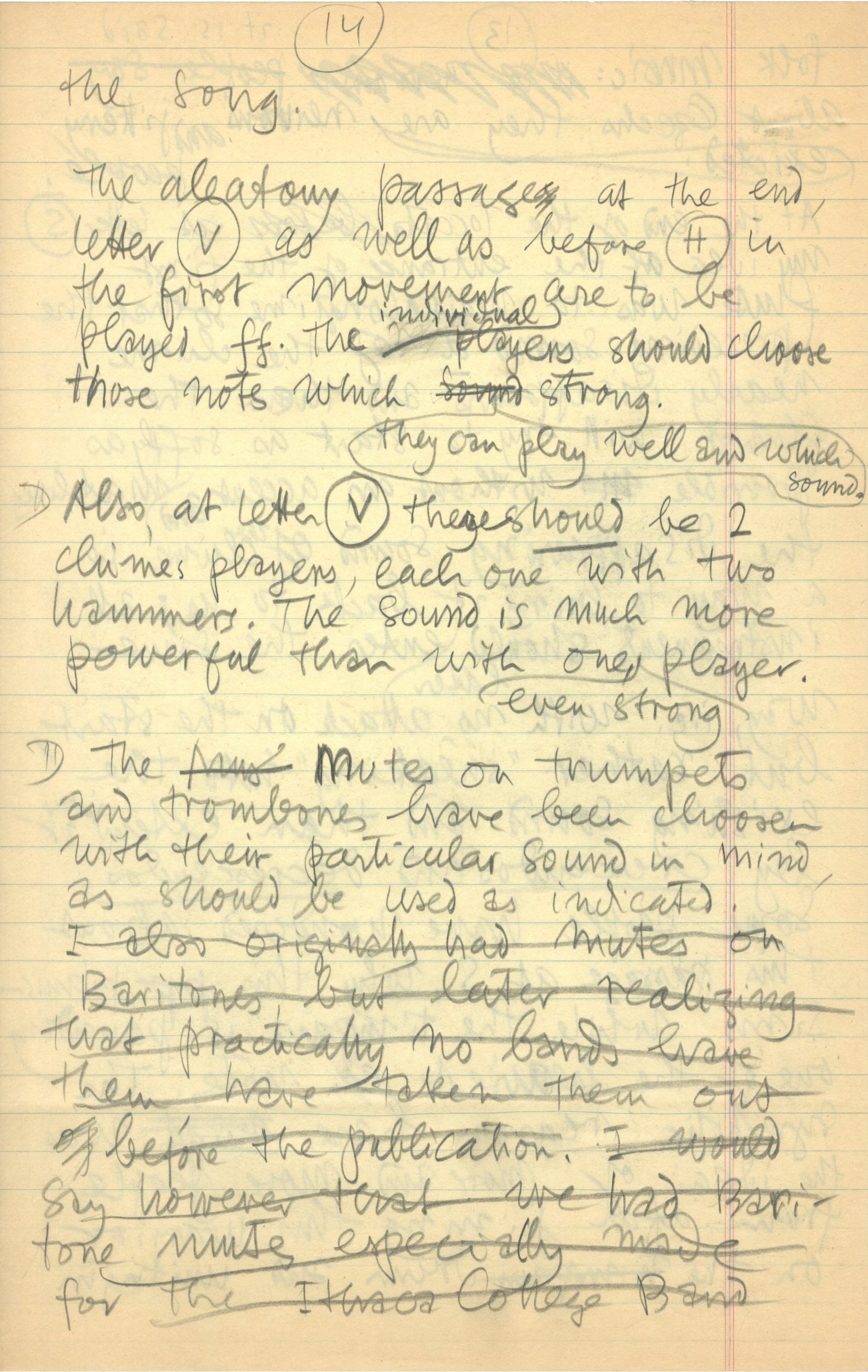

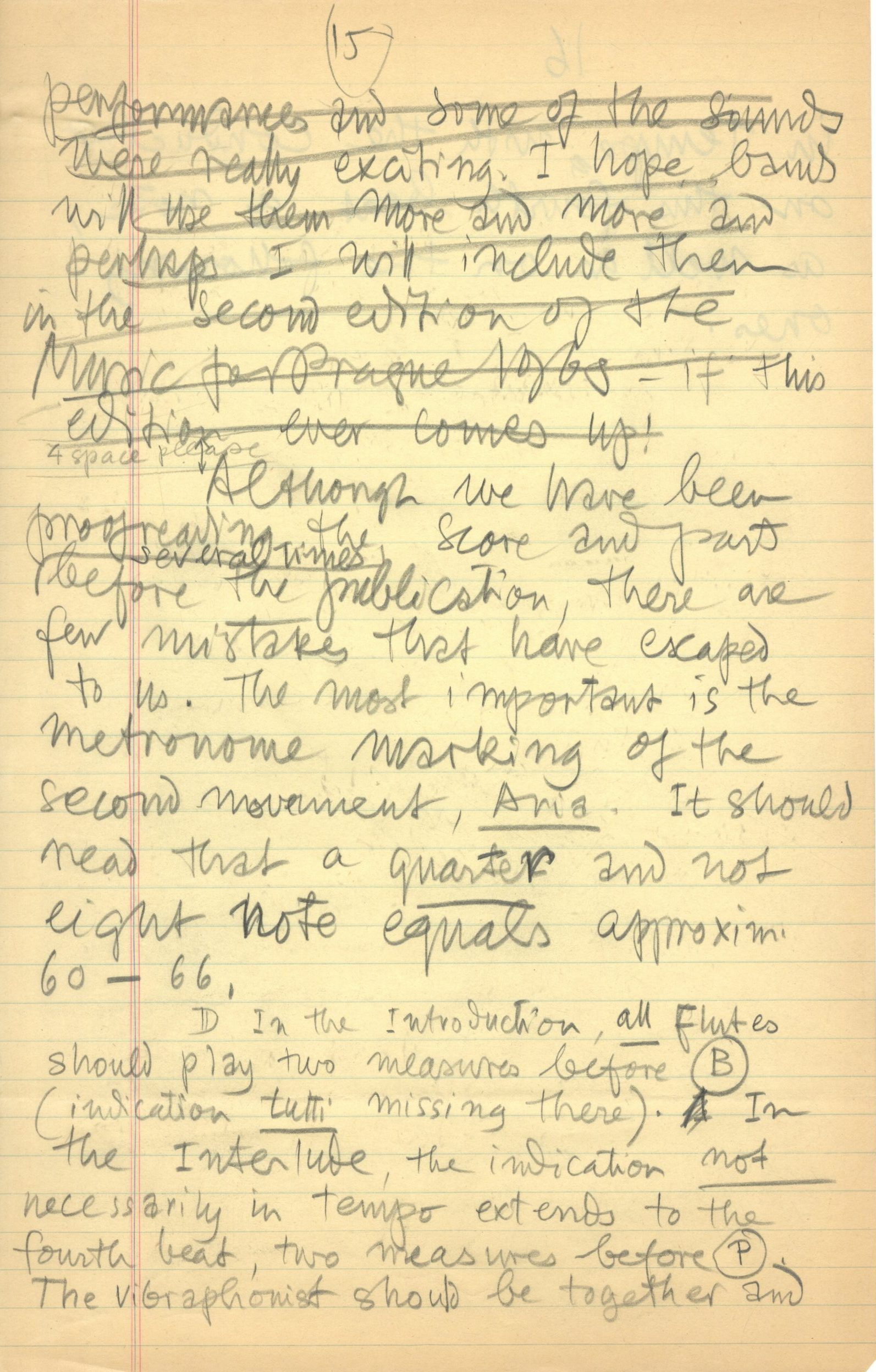

In the years since the work’s premiere, several conductors—and a few scholars—have published performance guides and articles analyzing the piece. Of particular value, however, are Karel Husa’s own remarks on his composition. The Archive preserves several such documents.

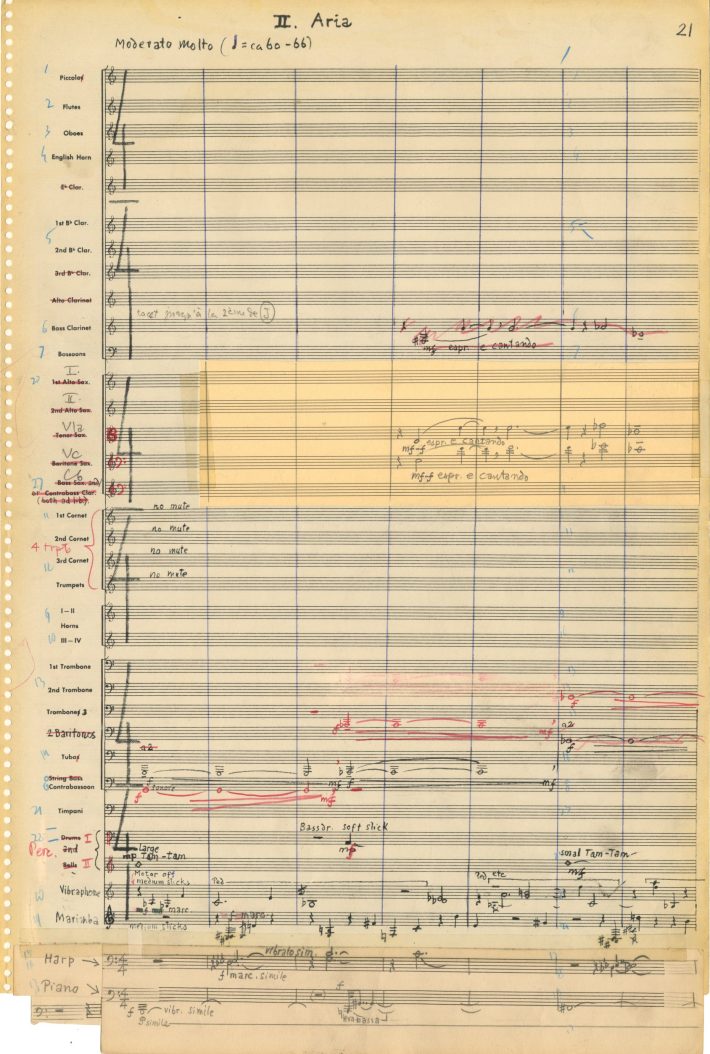

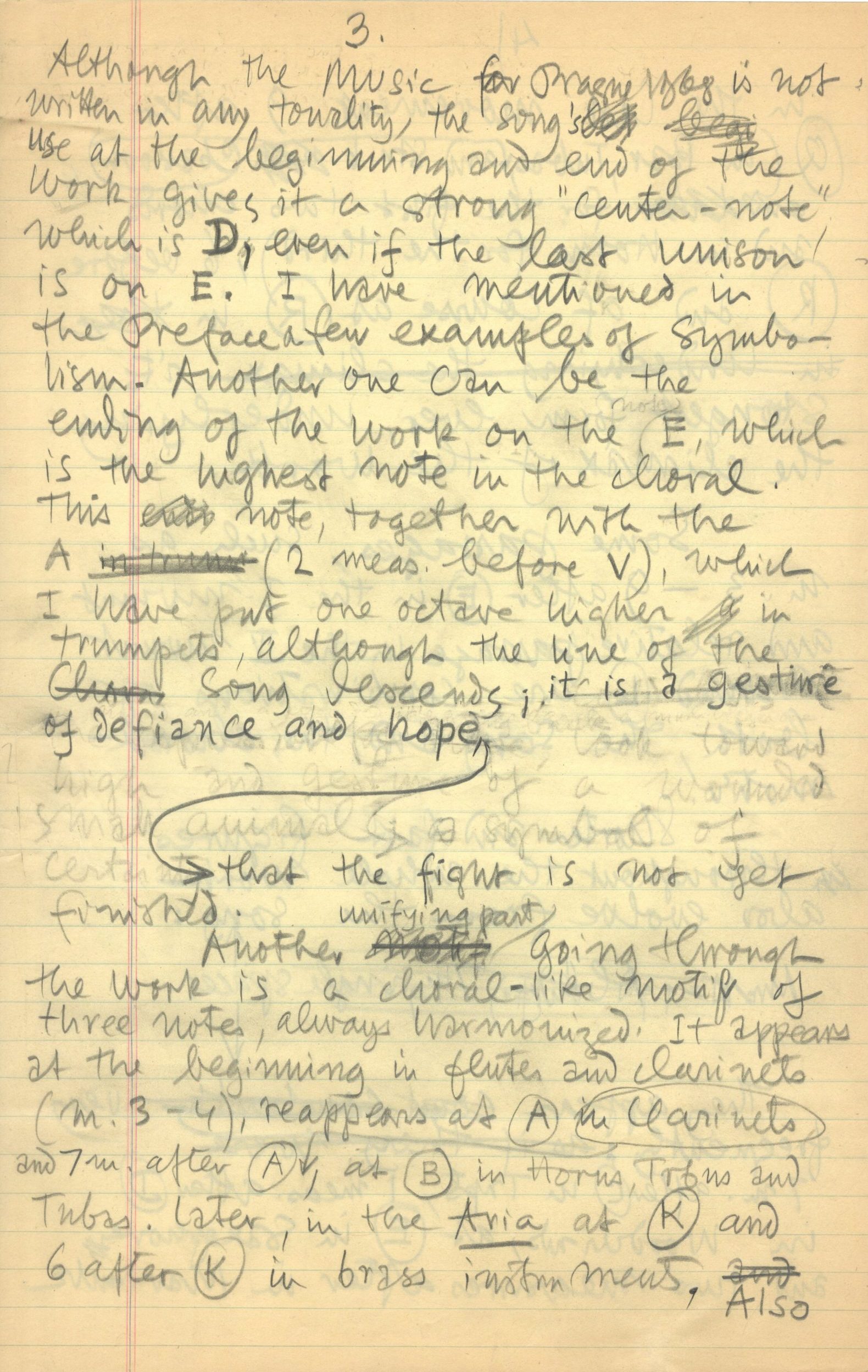

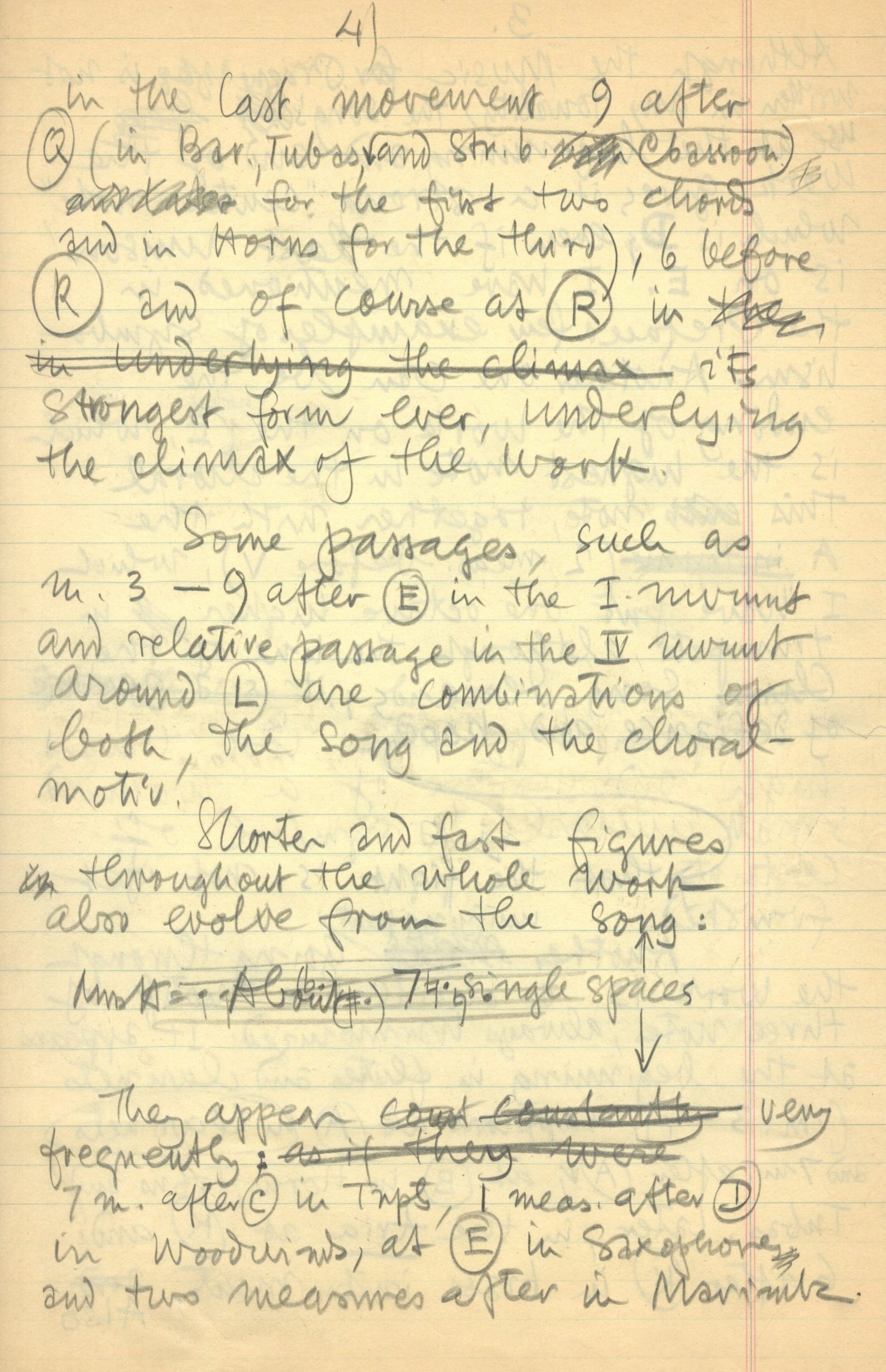

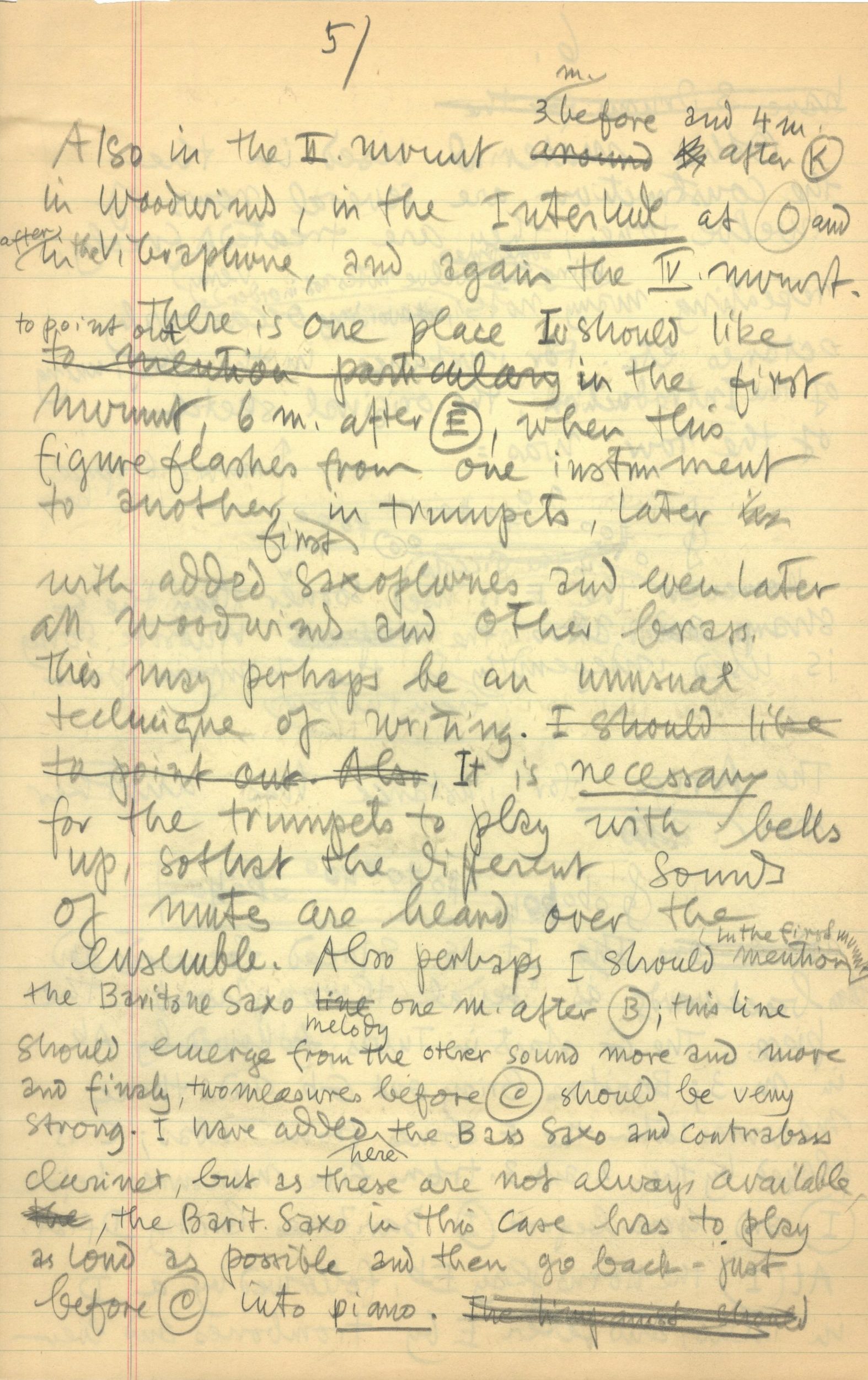

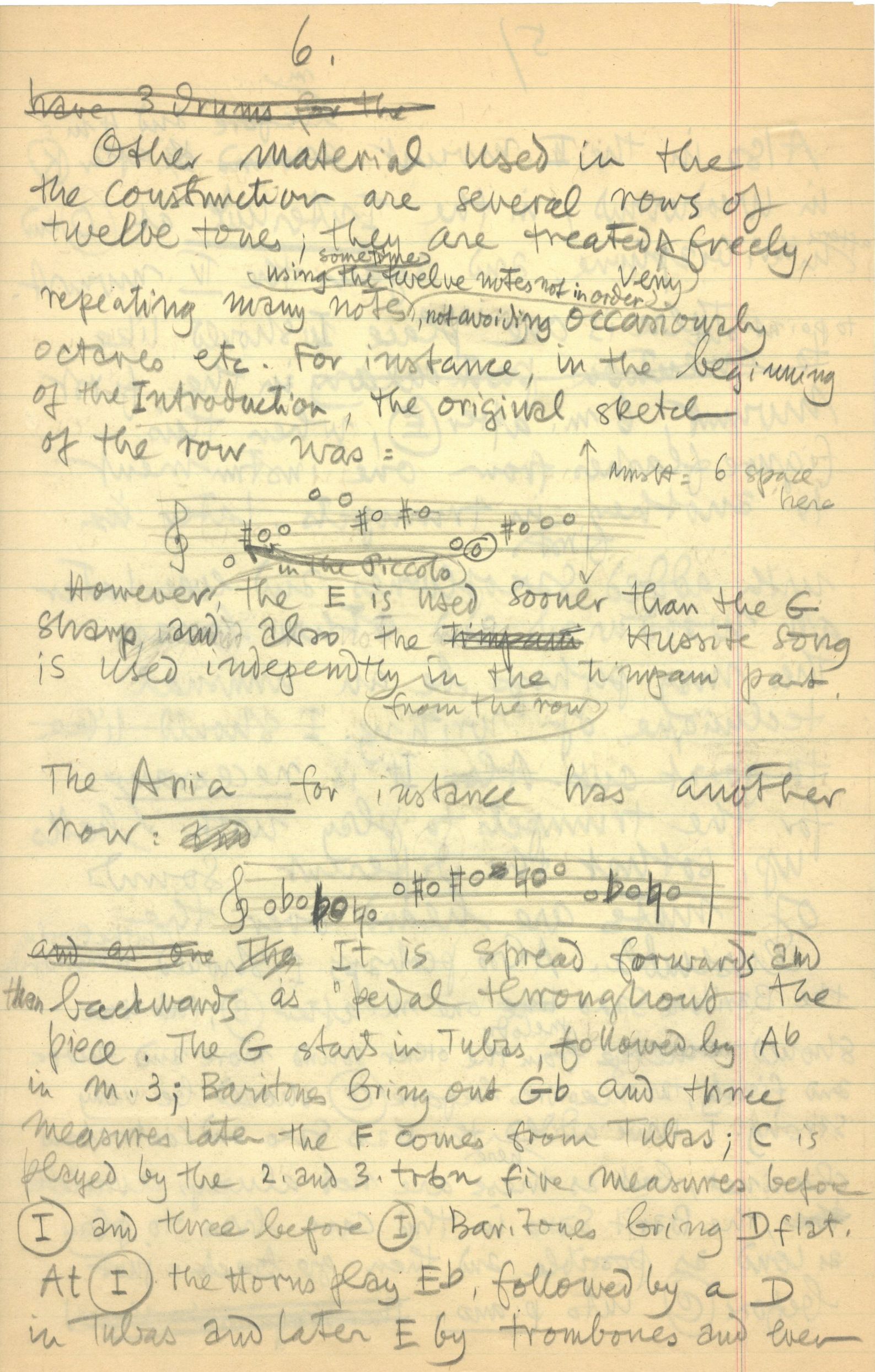

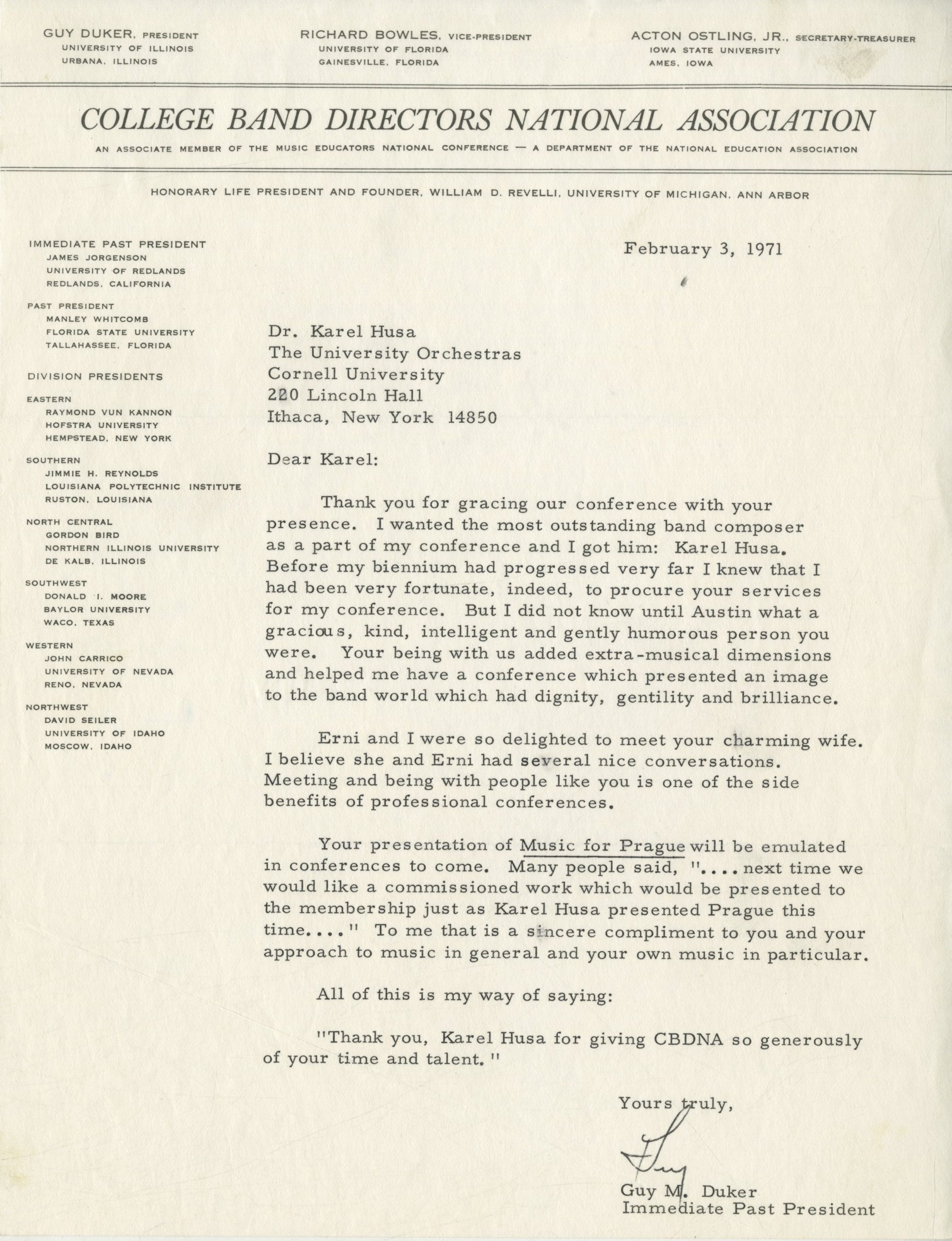

In 1971, about two years after the work’s premiere, Karel Husa was invited to give a brief presentation on Music for Prague 1968 at the College Band Directors National Association national conference hosted that year by the University of Texas. A copy of Husa’s handwritten draft of his presentation is preserved in the Archive, and his final remarks were later published in The College and University Band: An Anthology of Papers from the Conferences of the College Band Directors National Association, 1941-1975.[3]

In his presentation, Husa began by recalling the inspiration for the work and its programmatic connection:

It was in late August 1968 when I decided to write a composition dedicated to the city in which I was born. I have thought about writing for Prague for some time because the longer I am far from this city—I left Czechoslovakia in 1946—the more I remembered the beauty of it. I could even say that in my idealisation, I actually see Prague even more beautiful.

During the tragic and dark moments for Czechoslovakia in August 1968, I suddenly felt the necessity to write this for so long meditated piece. My friend and colleague, Dr. Kenneth Snapp, then Director of Bands at Ithaca College, had mentioned to me the possibility of commissioning a work should the Ithaca College Band play at the MENC Convention in January 1969. Although this was not yet definite, I was sure that the music I would write for Prague would be scored for the concert band, [a] medium which I have admired for a long time. The combination of wind and brass instruments with percussion fascinated me and the unexplored possibilities of new sounds and combinations of instruments attracted me for some time.

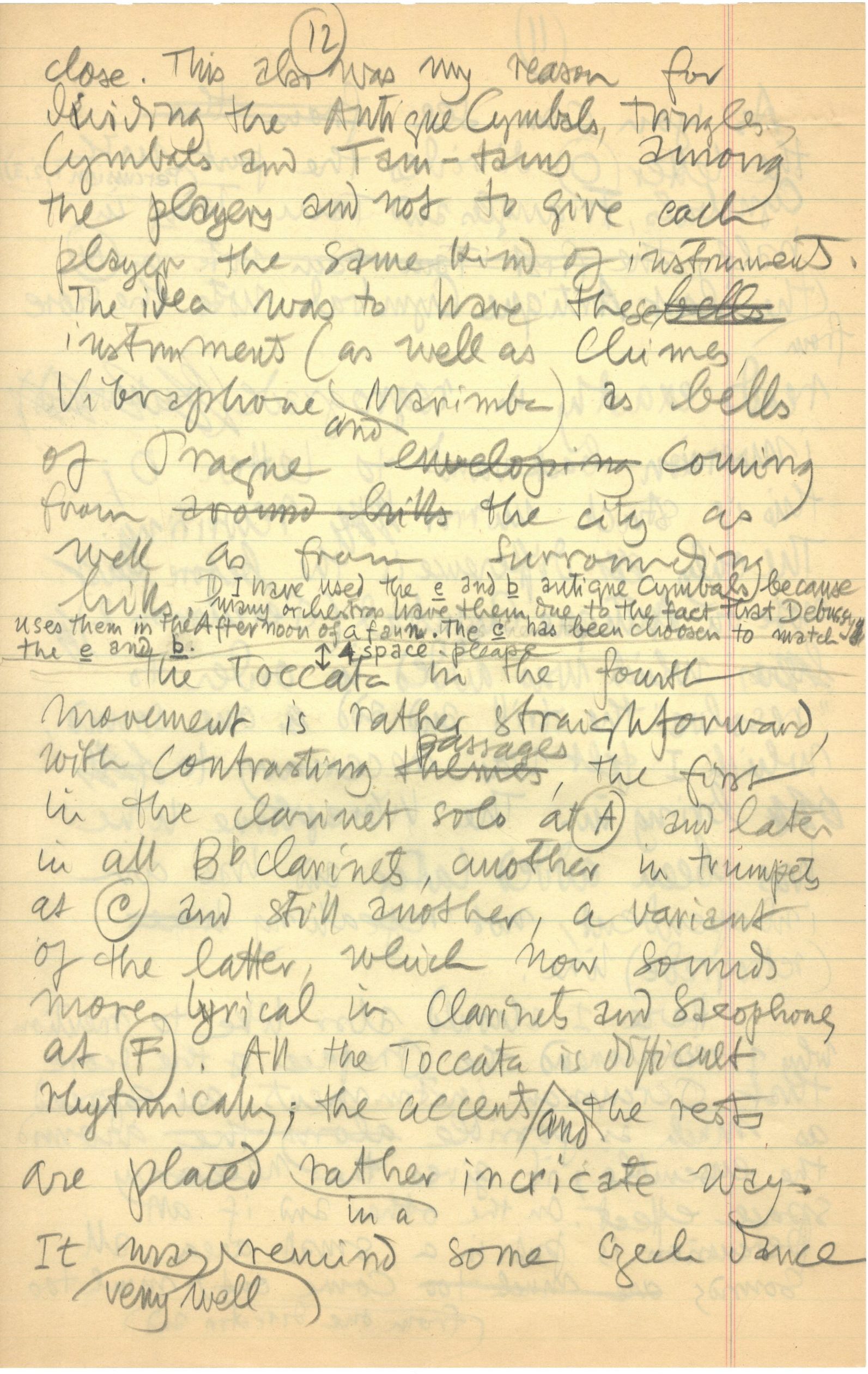

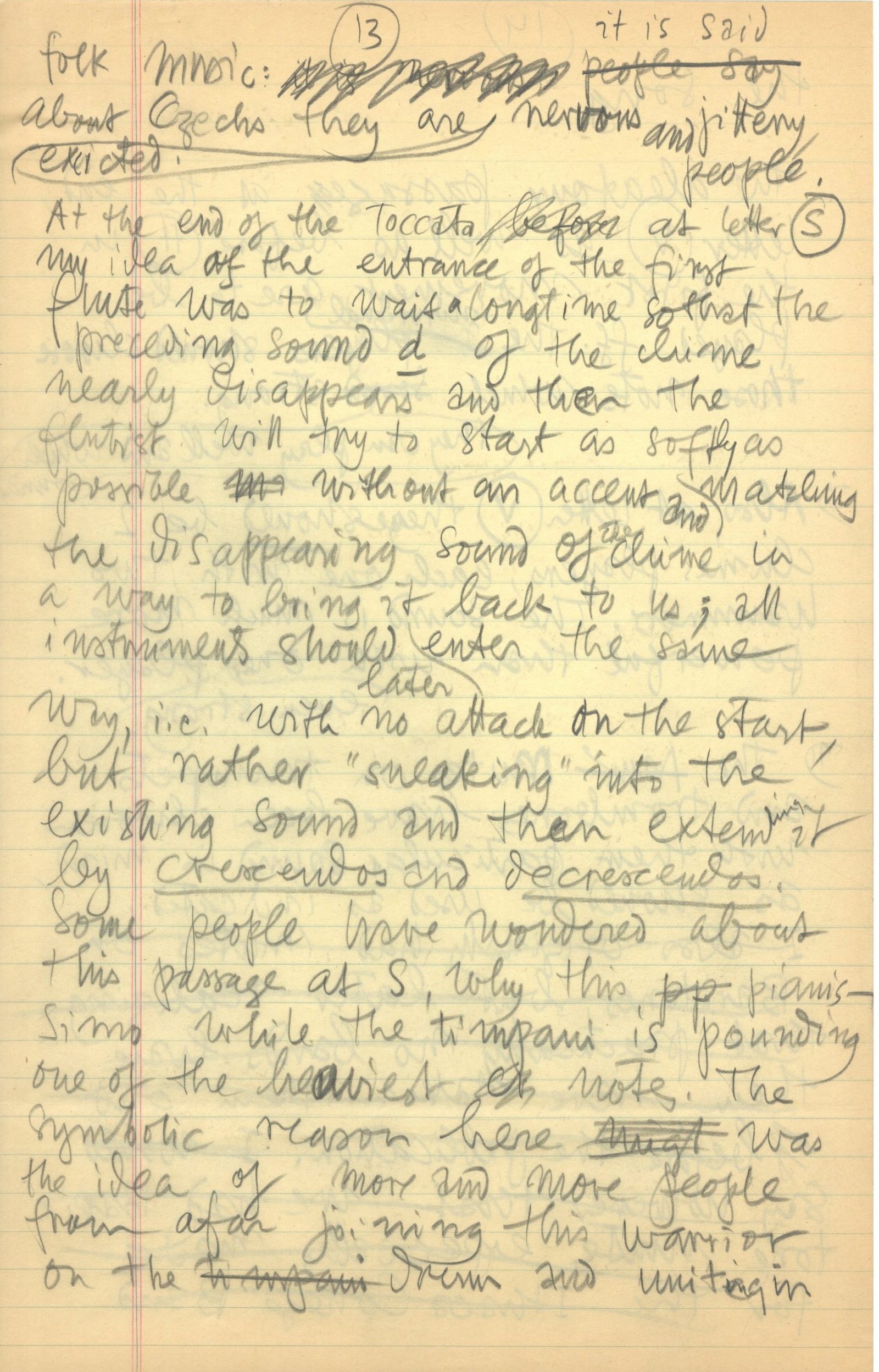

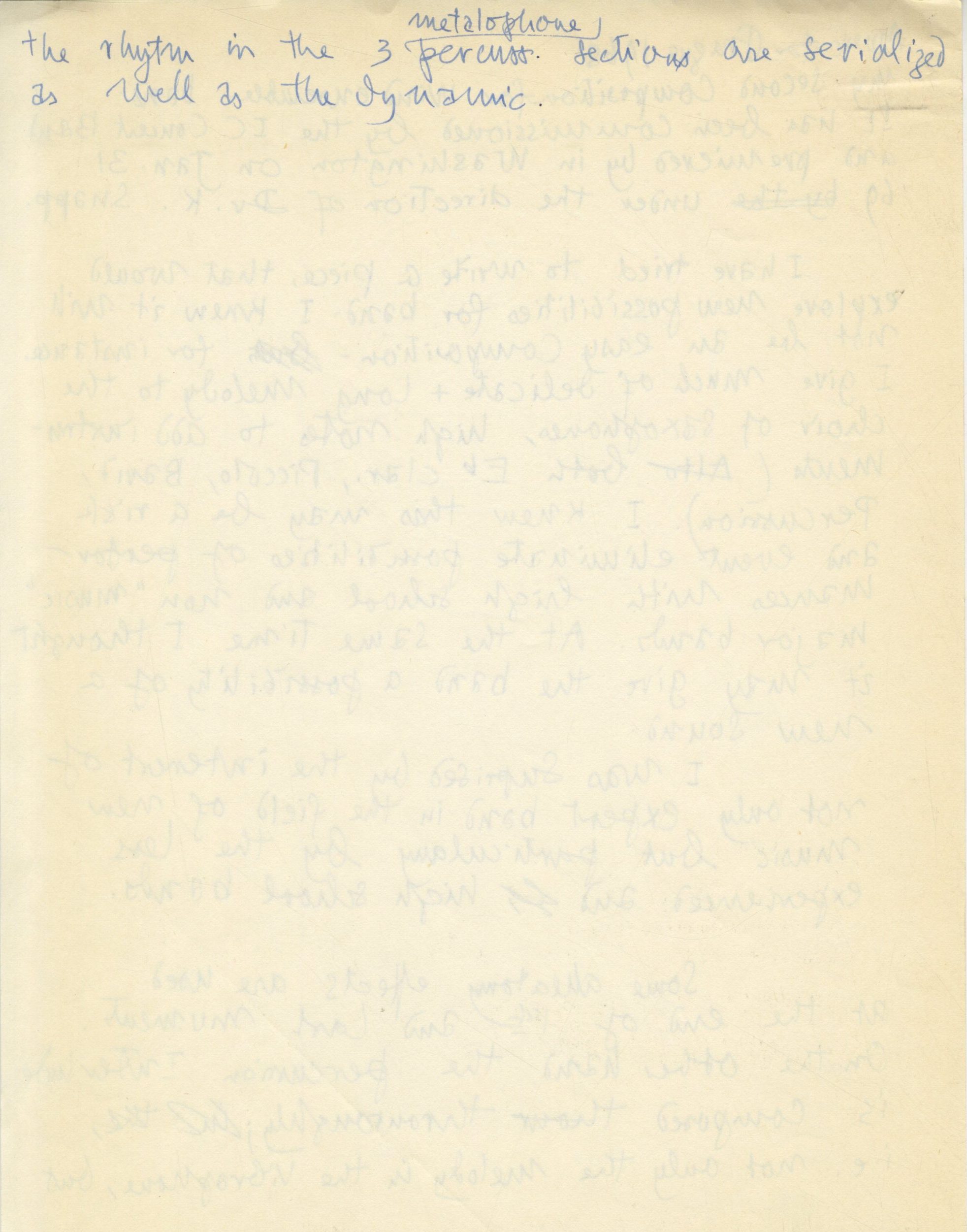

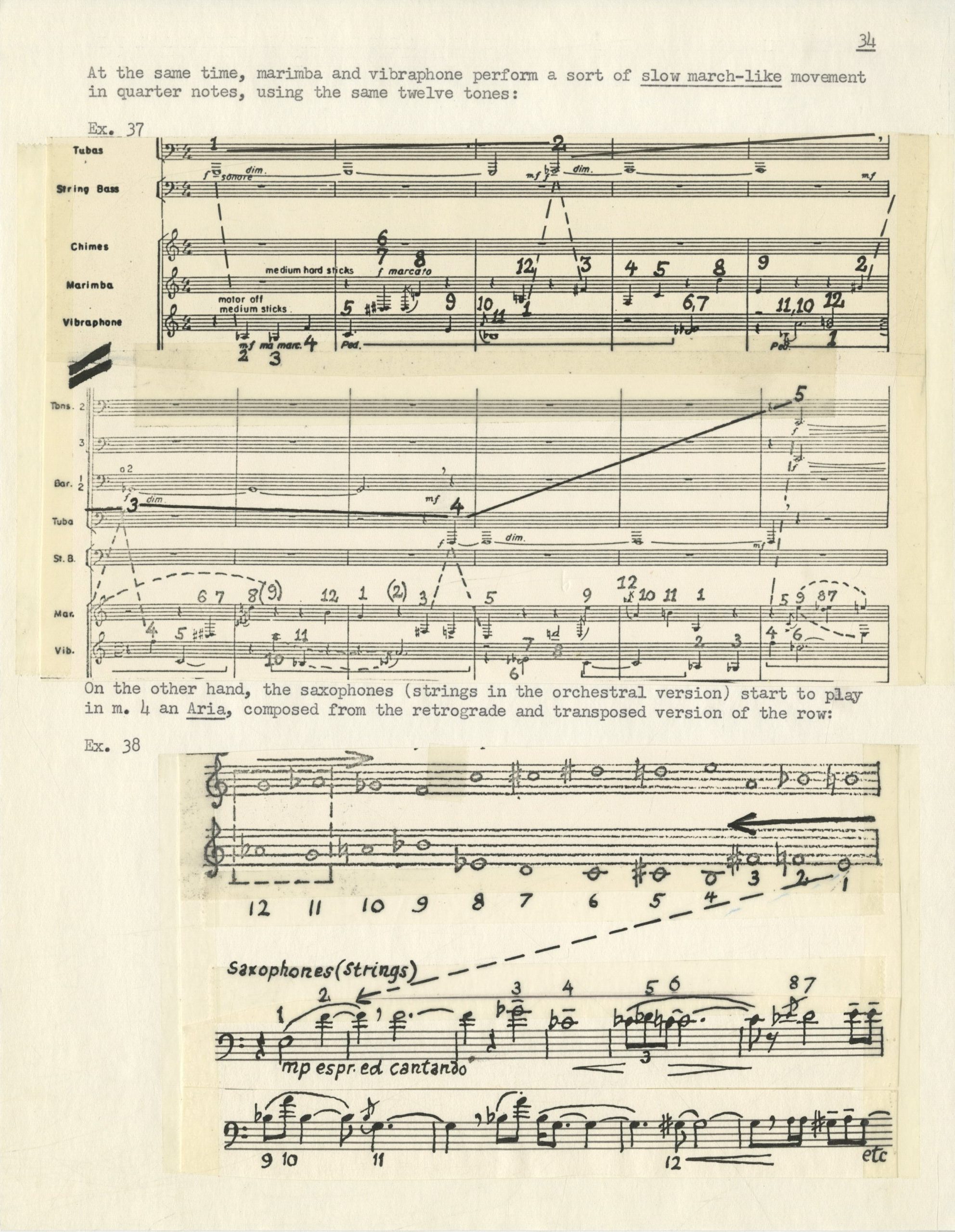

The remainder of his remarks outline key motifs, serial techniques, and other structural elements, expanding on the overview provided in the composer’s foreword to the score.

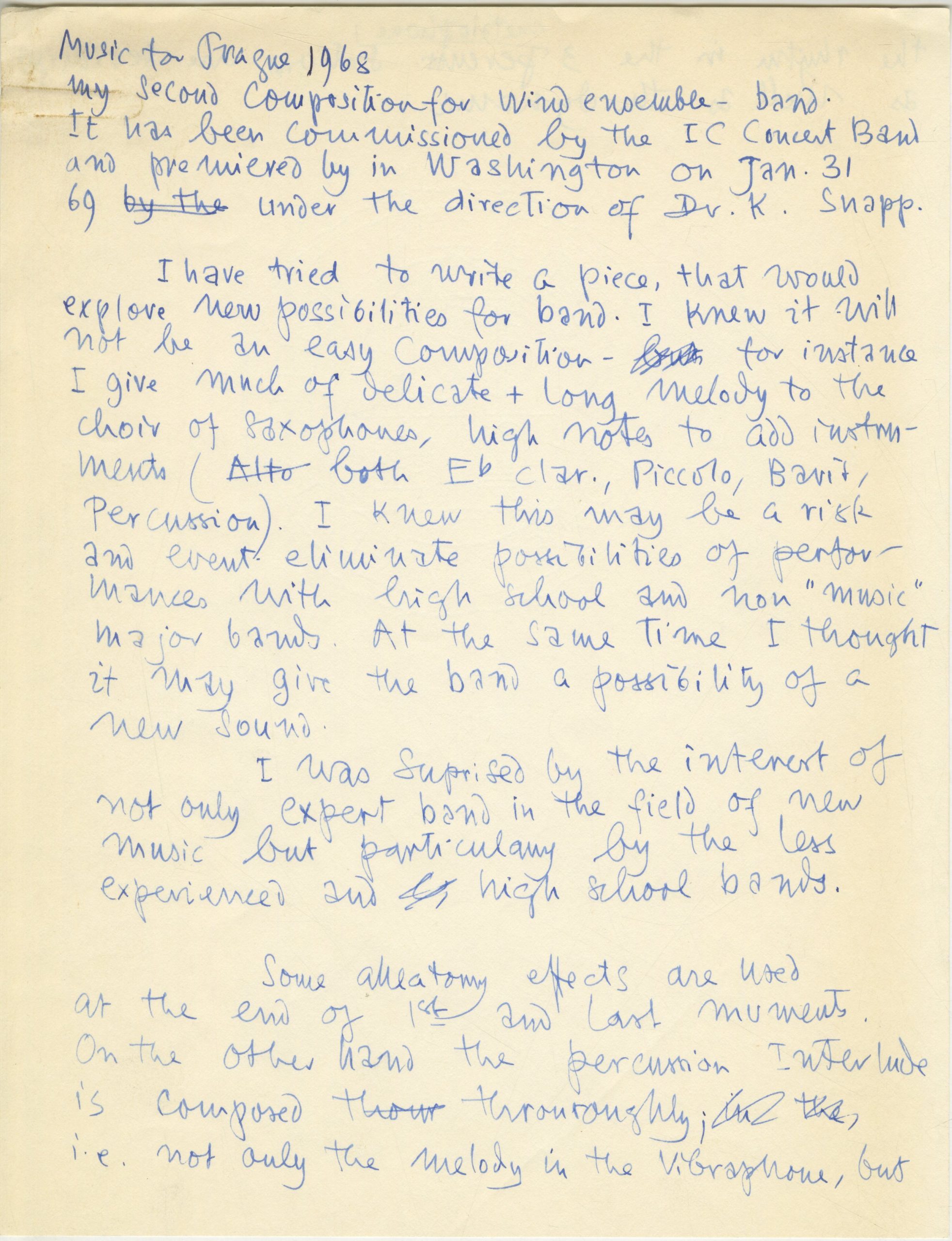

In another set of notes on the piece, Karel Husa describes his hope that the piece would “give the band a possibility of a new sound” and ruminates more generally on the then unconventional compositional techniques he employed in the composition:

I have tried to write a piece, that would explore new possibilities for band. I knew it will not be an easy composition—for instance I give much of [a] delicate and long melody to the choir of saxophones, [and] high notes to odd instruments (both E-flat clarinet, piccolo, baritone, percussion). I know this may be a risk and events eliminate [the] possibilities of performances with high school and non “music” major bands. At the same time I thought it may give the band a possibility of a new sound.

I was surprised by the intent of not only expert band[s] in the field of new music but particularly by the less experienced and high school bands.

Some aleatory effects are used at the end of [the] 1st and last movements. On the other hand the percussion interlude is composed thoroughly, i.e., not only the melody in the vibraphone, but the rhythm in the 3 percussion sections are serialized as well as the dynamic.

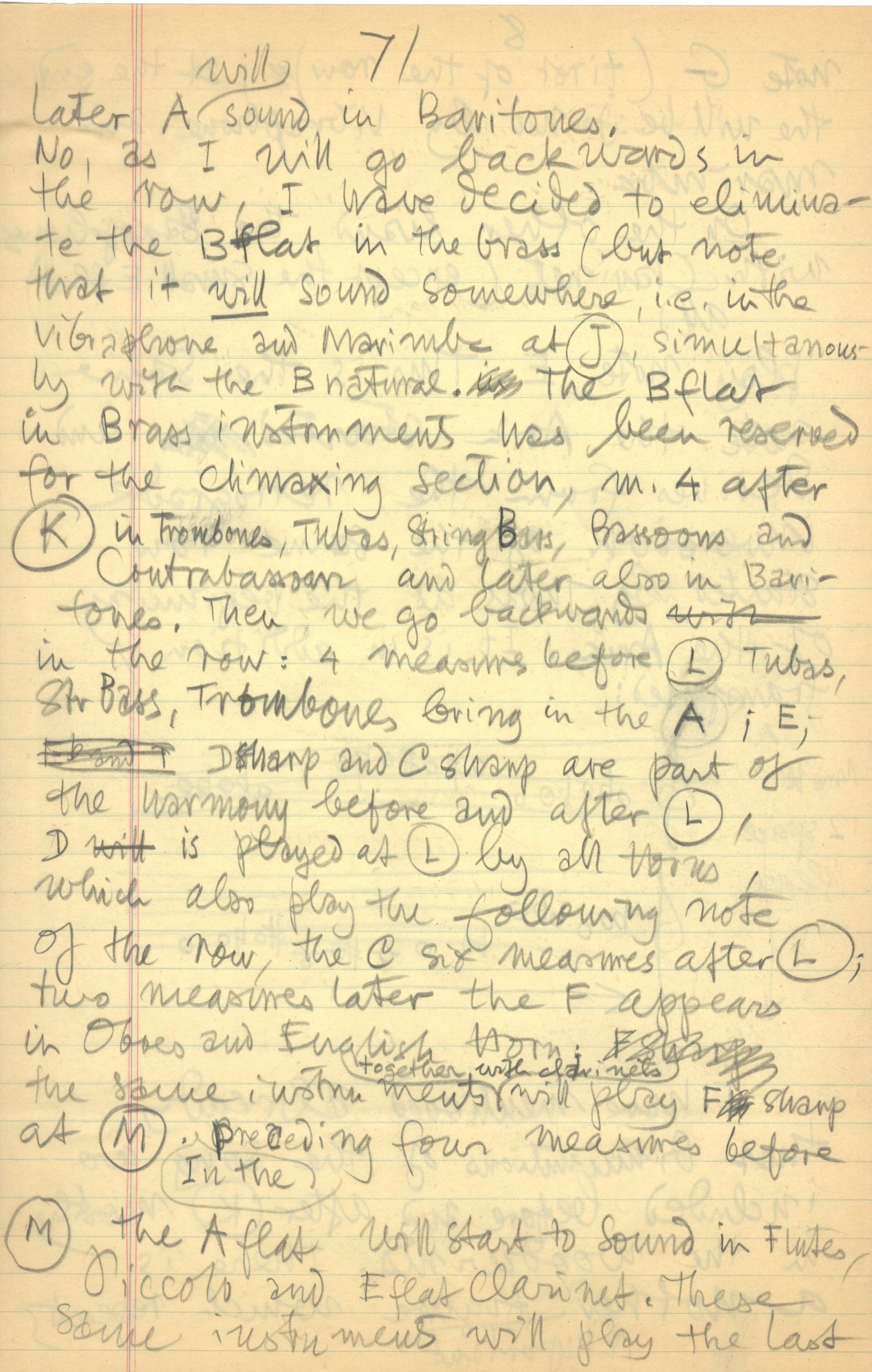

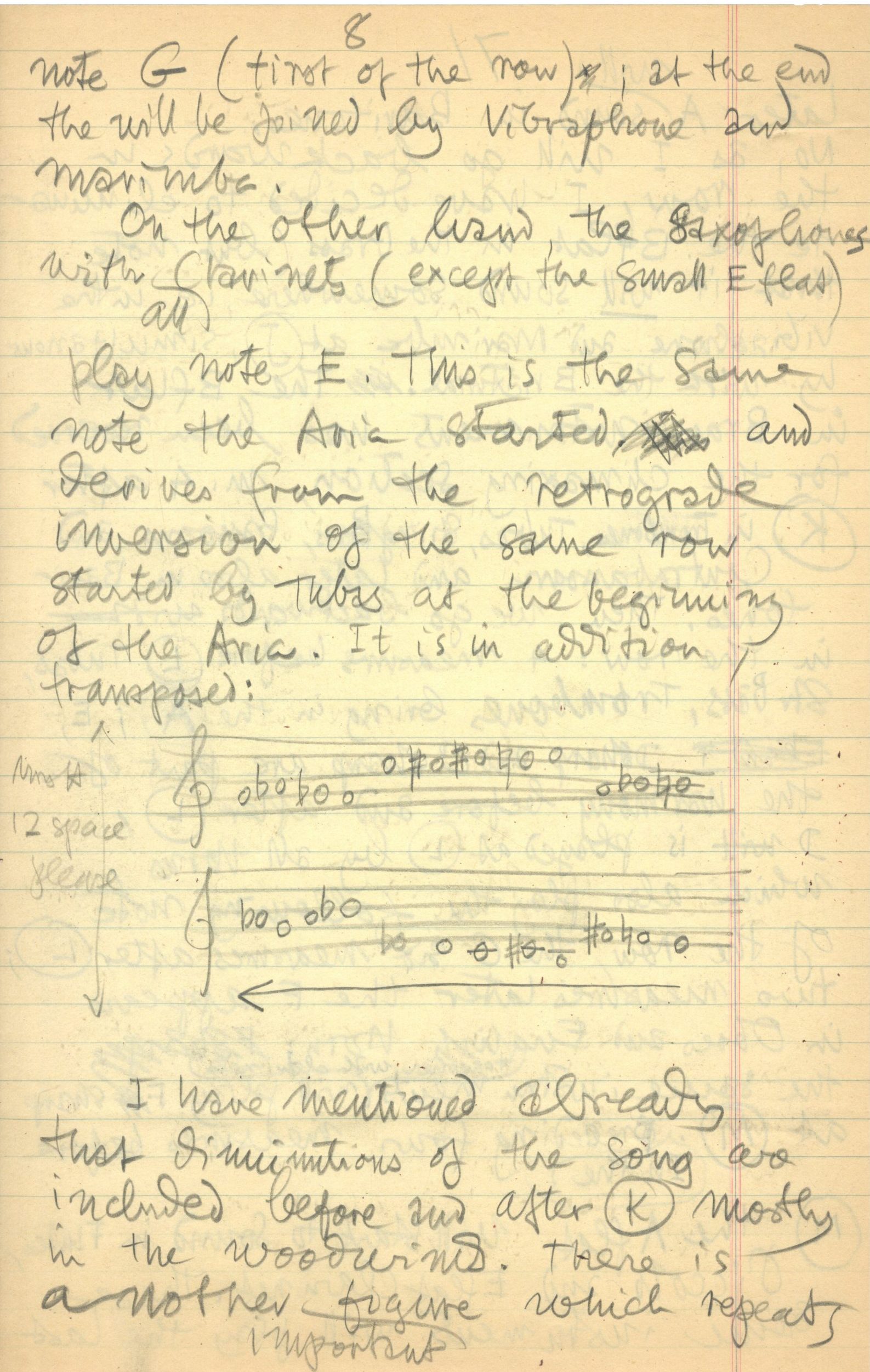

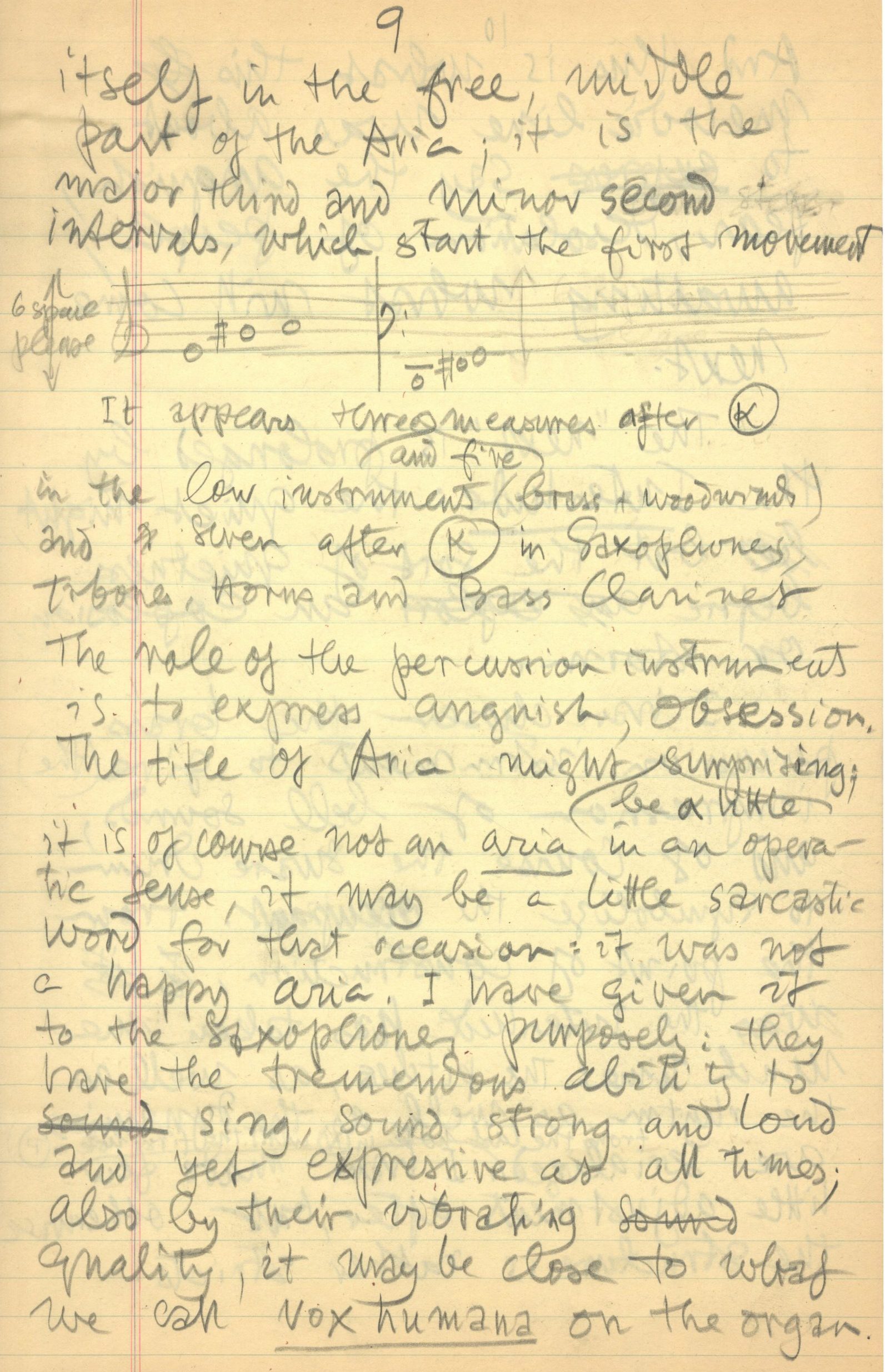

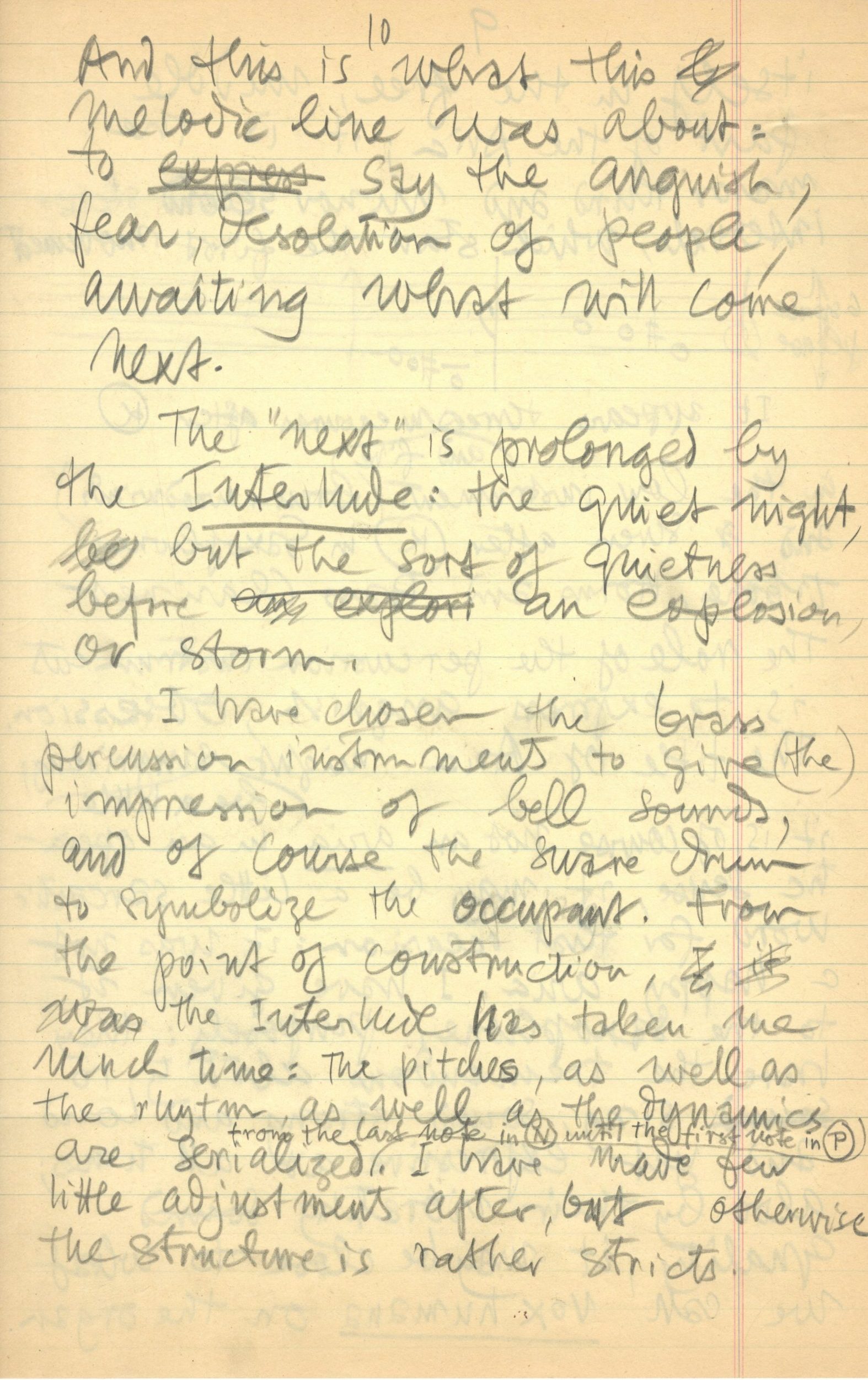

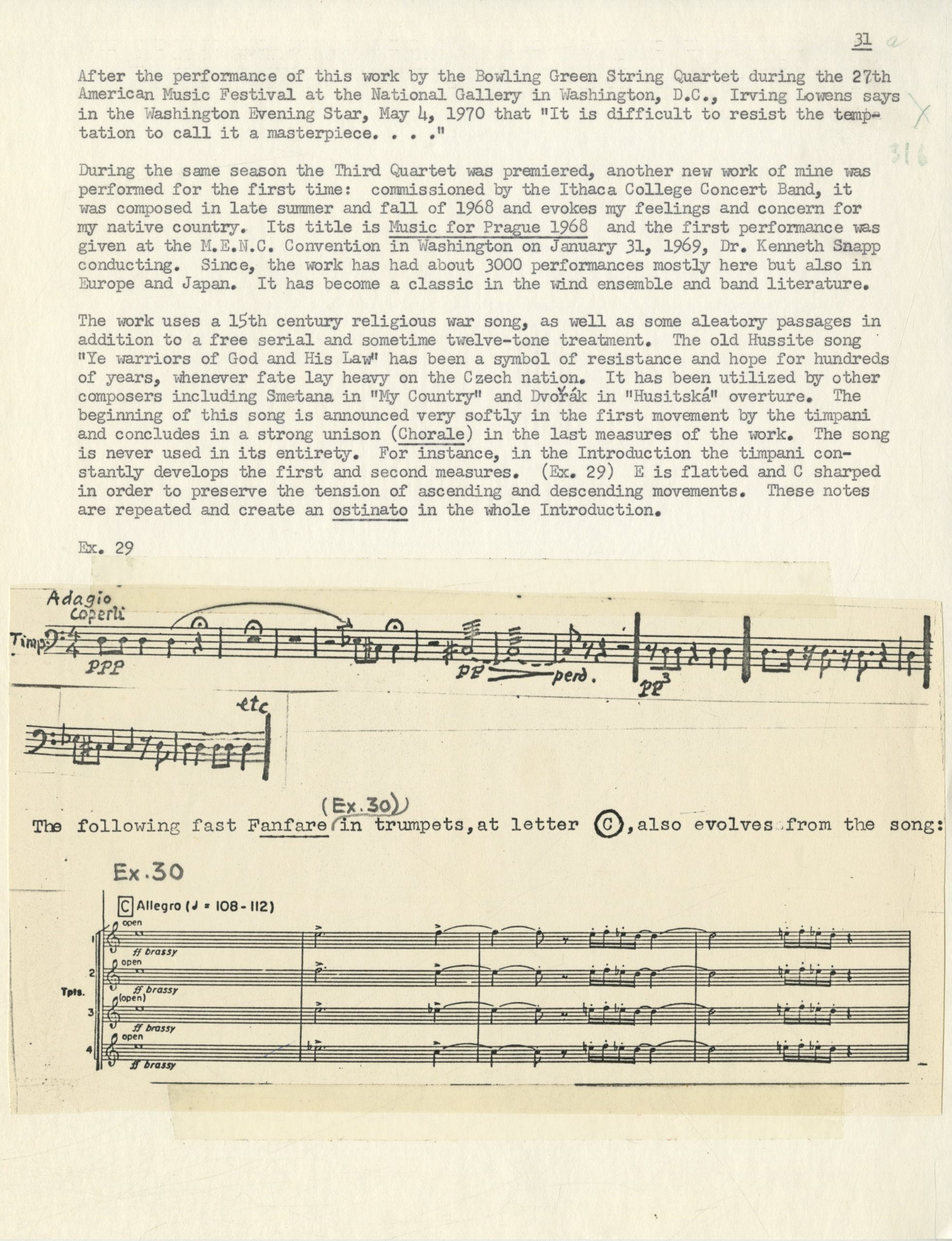

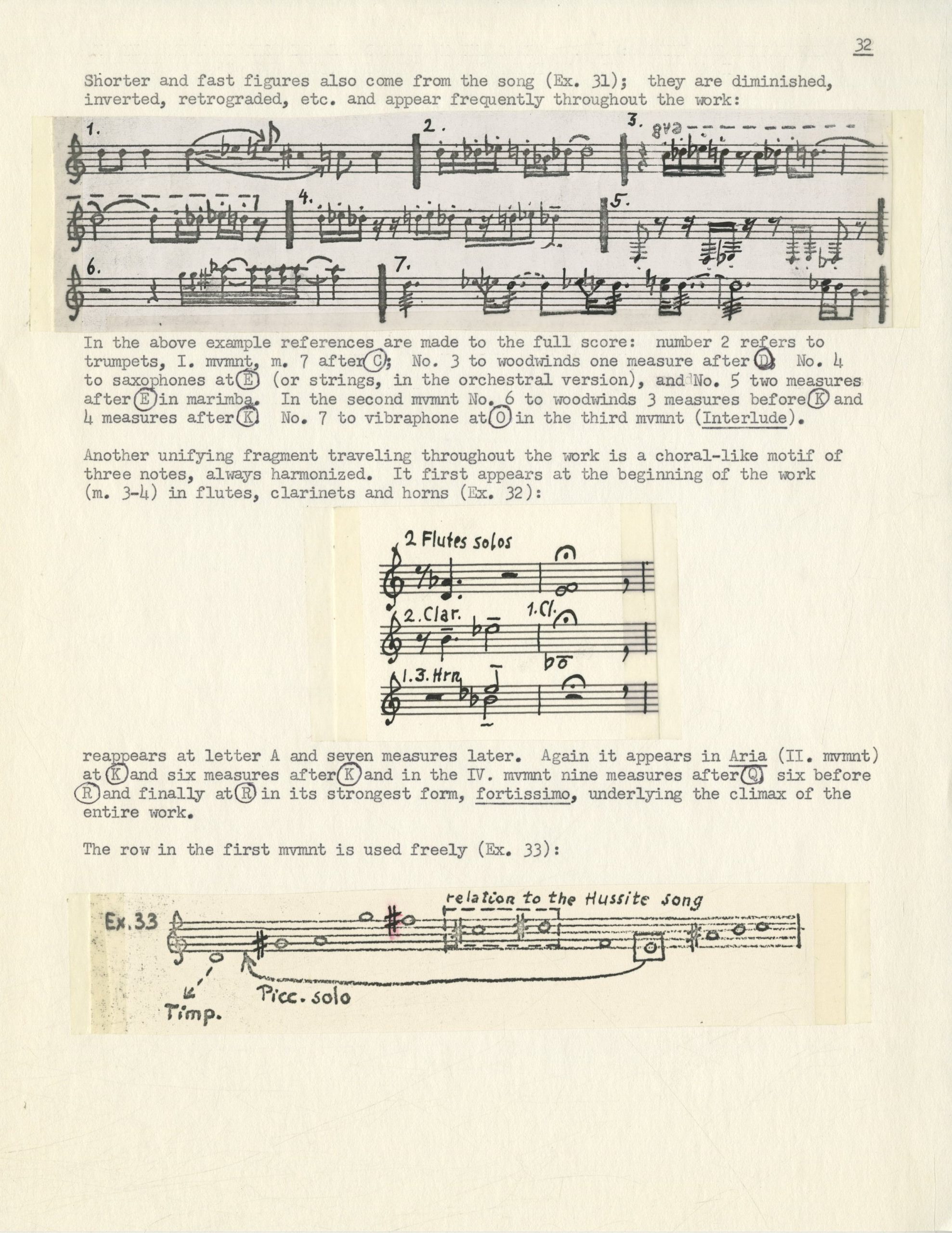

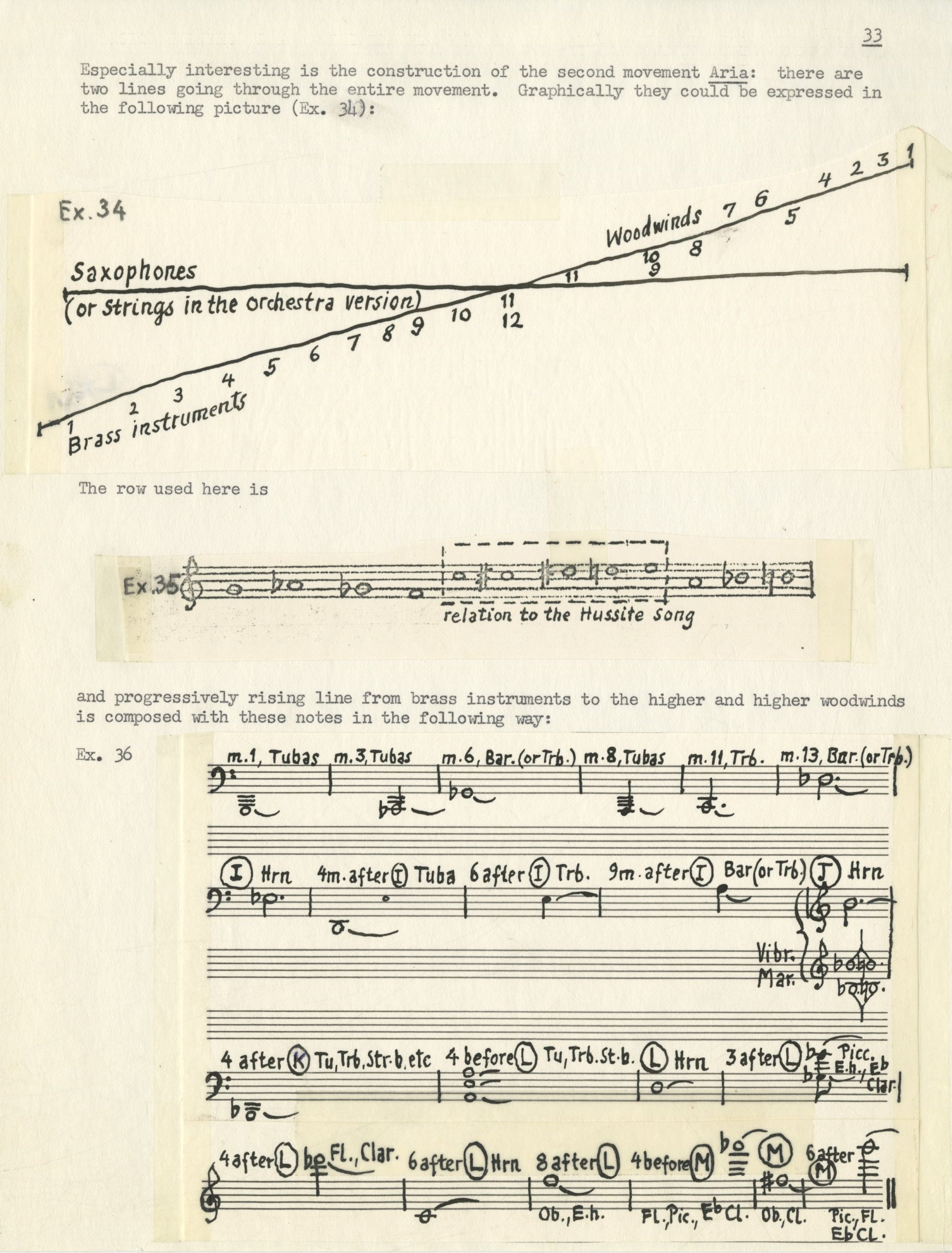

A third, intriguing analysis of Music for Prague 1968 is included within what appears to be an unfinished autobiographical essay. Husa intersperses these brief memoirs with commentary and analyses of several of his compositions, Music for Prague 1968 included. In this analysis, Husa reiterates the main compositional elements of the piece, particularly the fragmentation of the Hussite war song, his free use of two primary tone rows, and the work’s key programmatic elements. Unlike his previous comments on the piece, however, this analysis includes a more detailed description of the construction of the second movement (Aria). (N.B. A similar chart outlining the large-scale application of Row B across the entire movement is reproduced in Lawrence W. Hartzell’s analysis of the composition in Musical Quarterly.[4])

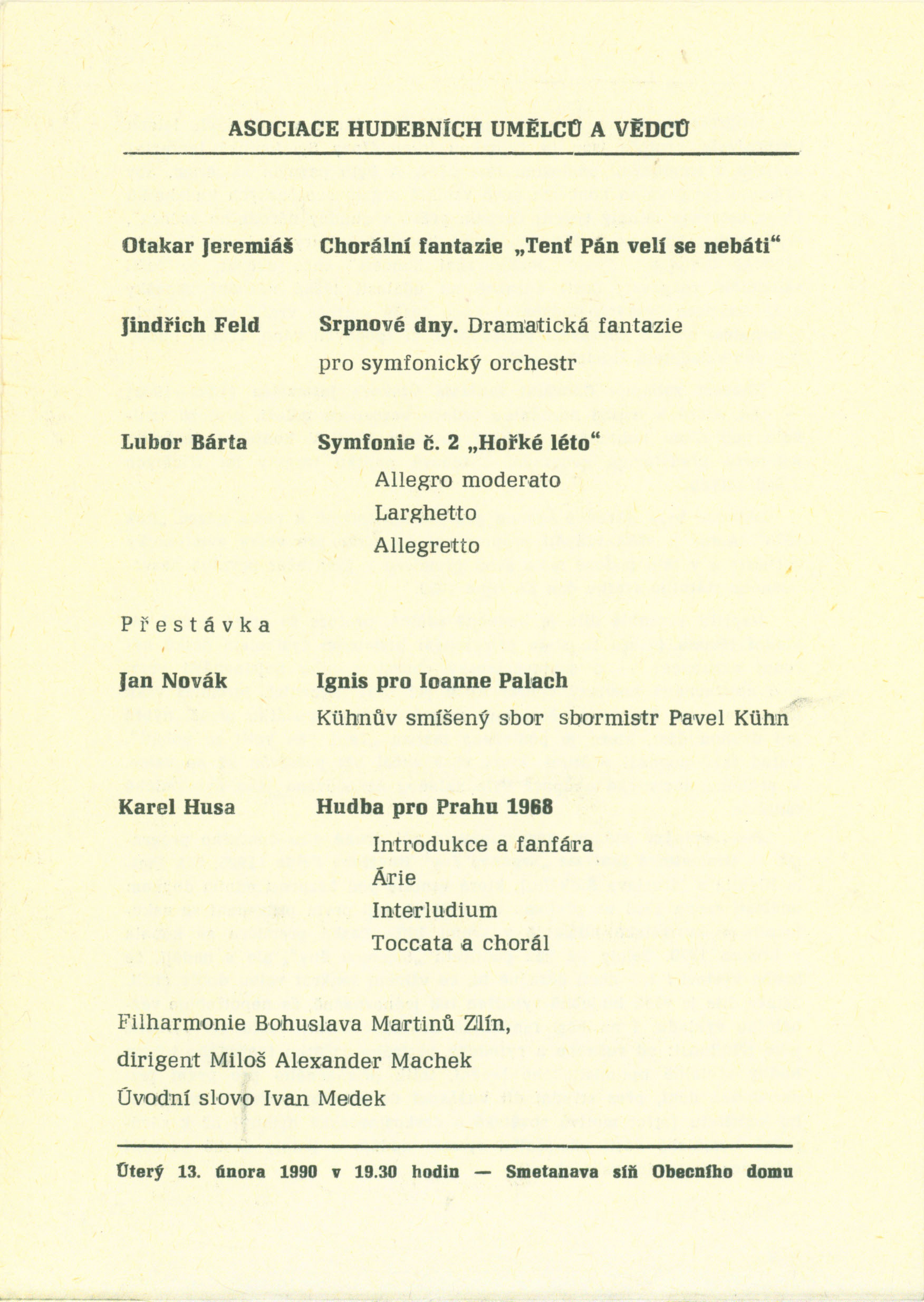

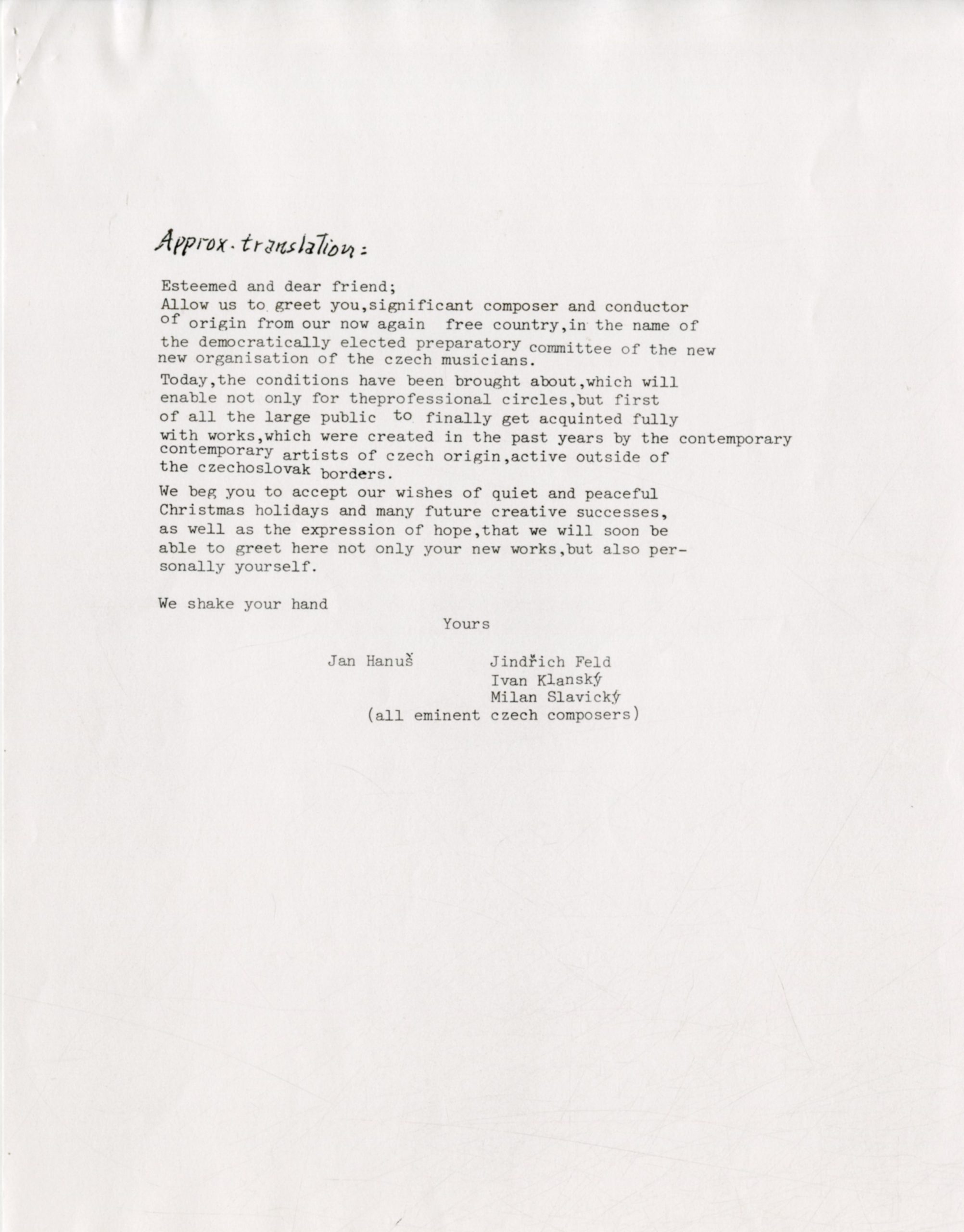

In the years immediately after the premiere of Music for Prague 1968, Karel Husa—already a frequent guest conductor and clinician—received dozens of invitations from professional ensembles, colleges and universities, high schools, and festivals organizers to conduct Music for Prague 1968. Perhaps the most meaningful of these invitations came in early 1990, just a few months after the Velvet Revolution brought an end to Communist rule in Czechoslovakia. Before the revolution, Husa’s music had been banned in his homeland—first, in 1949, after the composer lost his citizenship for refusing to return to Czechoslovakia from his studies in Paris to renew his passport, and again in 1969 as a direct response to Music for Prague 1968. With the revolution, such restrictions were eliminated, and the path cleared for a homecoming for Husa and his music. A welcoming letter from the newly organized Union of Czech Composers and Concert Artists (Svazu českých skladatelů a koncertních umělců) in mid-December was followed swiftly by news from Husa’s European publisher that an orchestra (the Czech State Symphony Orchestra, Filharmonie Bohuslava Martinů) was preparing to present the Prague premiere of Music for Prague 1968 in February 1990 as part of a gala concert of music by native Czech composers. Husa immediately made arrangements to be there to conduct his work.

Husa immediately made arrangements to be there to conduct his work at the gala concert. His homecoming was widely celebrated in the press, and dozens of colleagues wrote to the composer expressing their congratulations for the event and, more importantly, the new political freedoms it represented for Czech citizens.

The personal reflections Husa embedded in Music for Prague 1968 are not unique within his oeuvre. In 1970, Husa completed Apotheosis of This Earth, another seminal work for concert band, which ruminates on environmental destruction and other critical threats to life on Earth, and his 1975 ballet Monodrama (Portrait of an Artist), inspired by an essay by James Baldwin, addresses racial stereotypes and societal stratification.

In 1985, when asked to write a brief statement on his compositional philosophy for a display of his scores at the Ithaca College Library, Husa highlighted how his thoughts on world events had influenced his compositional philosophy:

I hope my music is marked by the life of today. It seems to me that in the past most of the arts had that same quality anyway.

Bach’s music reflects the religious and philosophical thinking of the eighteenth century, Beethoven’s the revolution and appearing romanticism, Debussy’s the beauty of colors, and Schoenberg’s the inner feelings of a man, often pessimistic, but true.

We live in a world which has seen incredible achievements in the sciences, including—unfortunately—the possibility of destroying this planet. We have visited the moon, are exploring space; yet we still have suffering, hunger, wars, loneliness, and tyranny. Freedom, probably the most important ingredient in the life of man, still does not exist on two thirds of this earth.

We have the beautiful, exalting, amazing, dramatic, tragic in more than sufficient cases. What more does one need for an inspiration?

[1] Mark D. Scatterday, “Karel Husa: Music for Prague 1968,” in Performance Study Guides of Essential Works for Band, ed. Kenneth L. Neidig (Galesville, MD: Meredith Music Publications, 2009), 42. Call number: MT 135 .P438 2009.

[2] Zachary Cairns, “Music for Prague 1968: A Display of Czech Nationalism from America,” Studia Musicologica 56, no. 4 (2015): 443–458. Available via JSTOR.

[3] Karel Husa, “Music for Prague 1968,” in The College and University Band: An Anthology of Papers from the Conferences of the College Band Directors National Association, 1941–1975, compiled by David Whitwell and Acton Ostling (Reston, VA: MENC, 1977). Call number: ML1311 .C698 1977

[4] Lawrence W. Hartzell, “Karel Husa: The Man and the Music,” Musical Quarterly 62, no. 1 (1976): 87–104. Available via JSTOR.

Audio Excerpts

Performance by the Eastman Wind Ensemble conducted by Mark Davis Scatterday (2017). Streaming audio available to UR/ESM community.

Performance by the Los Angeles Philharmonic conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen (2009). Streaming audio available via NAXOS.

Rehearsal of movement 1 (Introduction and Fanfare) by the United States Marine Band under director Col. Jason K. Fettig. Available via YouTube.

For further information, please inquire at the Ruth T. Watanabe Special Collections department.

A full finding aid for the Karel Husa Archive is available online.