Published on Apr 25th, 2022

1925: The first American Composers’ Concert

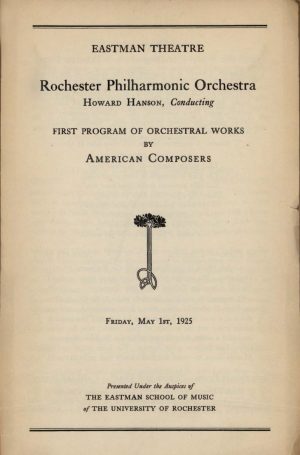

Ninety-seven years ago this week, on May 1st, 1925, a “Concert of New Works by American Composers” took place in the Eastman Theater, marking the first of what would be named the American Composers’ Concerts at the Eastman School. The launch of the American Composers’ Concerts represented the realization of the first of Howard Hanson’s initiatives in the promotion of American music. Moreover, their launch heralded the beginning of an era when the Eastman School of Music would be publicly identified with the promotion of both American music and the status of the American composer.

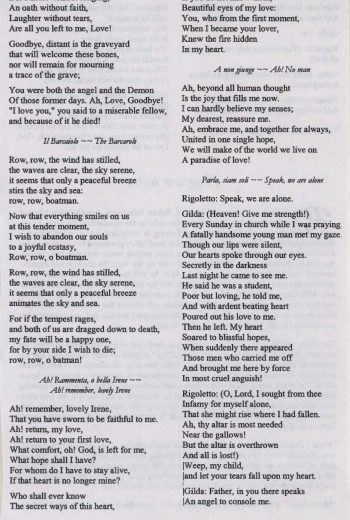

►printed program, May 1st, 1925

As a young professional—and we should recall that he began his teaching career as a young professor at the age of 20 (!)—and then as the newly appointed Director of the Eastman School of Music in 1924, one of Howard Hanson’s earliest concerns was that “the lot of the American composer was not necessarily a uniformly happy one” in that young composers repeatedly suffered having their manuscripts rejected out of hand, and also rarely or never hearing their orchestral music performed.[1] In Hanson’s own experience, while teaching at the College of the Pacific in California (1916-21), his two orchestral tone poems Before the Dawn and Exhaltation had proven too difficult for the student orchestra at his disposal; he was eventually able to hear both works performed by the Los Angeles Symphony Orchestra (today the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra) in 1920. Later, during his three years (1921-24) as a Fellow at the American Academy in Rome, he had enjoyed several opportunities to hear his works performed by professional orchestras, but he returned home to the U.S.A. keenly aware that many a young composer did not find such opportunities. Without those opportunities, Hanson reasoned that young composers would be hampered in their development and any potential for the development of a home-grown American musical art would be handicapped. To meet this problem, Hanson envisioned providing a forum whereby composers could hear their own works performed under professional circumstances. As background to his vision, a passage from his unpublished Autobiography is worth quoting in its entirety:

“The composer faces one problem which is indigenous to no other art except perhaps the art of the theater. For the composer, it is imperative that he have the opportunity of hearing what he has written. Without this experience, his whole career as a creative artist is jeopardized. In the case of the dramatist, it is at least possible to read a play without the accompanying dramatic action, unsatisfactory though such a performance may be. In music there is literally no substitute for performance.

“I desired, therefore, to attempt to set up at the Eastman School a ‘laboratory’ for young composers, whereas gifted young men might come and hear their works performed by a competent professional orchestra and under circumstances where compositions could be played without consideration of the box office. It was my hope also to invite critics of national importance to be members of our audience and to receive the benefit of their criticism.

“Both President Rhees and Mr. Eastman approved the idea, and I set about the task of finding foundation support for the financing of the project. Everyone to whom I spoke, including a number of New York City’s most influential critics, were enthusiastic about the plan and fully agreed that it could be of enormous help to the American composer.

“Raising the necessary funds was a different matter. I had the expressed interest and encouragement of one foundation. We had a number of meetings, all of which were most friendly and all equally abortive. The answer was always that my plan was excellent but needed ‘further consideration.’”

“Returning to Rochester from one of these meetings, I met George Eastman. He inquired how things were going. I replied that I was delighted with the progress of the school, but that my pet project for the American composer had yet to get off the ground. I then told him of my unsuccessful attempts to get a firm commitment of funds with which to begin the experiment. Mr. Eastman’s reply was typical of the man. “Howard,” he said, “you are not stupid! Why don’t you ask me for the money?” I did, and the American Composers’ Concerts have gone on without interruption for over forty years.”[2]

The founding of the American Composers’ Concerts entailed much activity on Hanson’s part. During his early months as Director of the Eastman School, he took advantage of his speaking engagements and guest conducting appearances to speak to all who would listen about the needs and challenges faced by American composers. Between November, 1924 and January, 1925 he published a series of eight articles in the Rochester Democrat & Chronicle to educate the local public on the problems of modern music and the challenges faced by American composers.[3] And in January, 1925, he issued a nationwide call for the submission of manuscripts by composers, openly promoting for the first time concert opportunities at the Eastman School. A committee of three—composer Ernest Bloch, conductor Albert Coates, and Hanson himself—examined the numerous submitted manuscripts to select those that would be rehearsed and performed in the first concert. The Eastman School committed itself to hosting each composer, as well as each composer’s travel, at its own expense. Further, leading music critics from around the nation would be invited to Rochester to cover the event. Newspapers across the nation, together with journals including Musical America, carried articles discussing Hanson’s aims for composers.[4] To ensure professional standards of performance, Hanson reached out to the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra to serve as the ensemble of choice under his own direction. Local publicity for the planned concert was heavy, and to maximize the opportunity for public exposure, Hanson established that the open rehearsals and the concert itself would be free of charge to the public, thereby establishing a practice that remained in place thereafter.

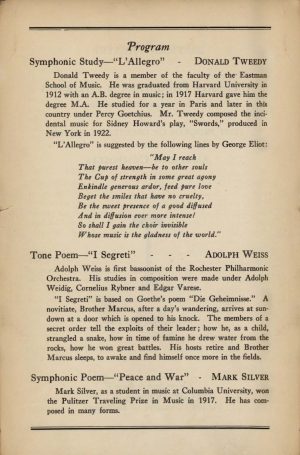

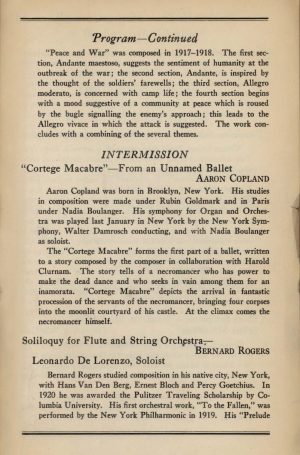

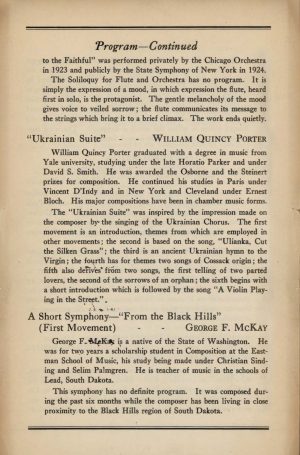

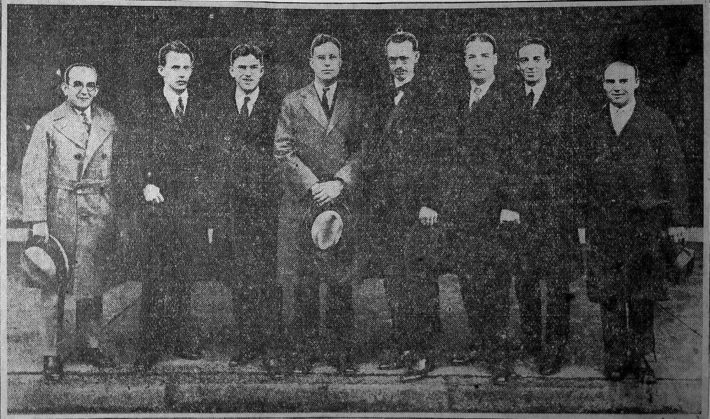

The inaugural American Composers’ Concert on May 1st, 1925 featured works by seven young composers, all of whom were present for the event: Aaron Copland, William Quincy Porter, Bernard Rogers, George McKay, Adolph Weiss, Mark Silver, and Donald Tweedy. True to Hanson’s intentions, several noted critics were also present for the concert. They included Olin Downes from The New York Times, Francis D. Perkins of the New York Herald Tribune, and Winthrop P. Tryon of the Christian Science Monitor. Of those three, Mr. Downes became something of a regular visitor to the Eastman School, where over the years he attended American Composers’ Concerts and Festivals of American Music until the year of his death.[5] The seven composers featured in the concert all went to respectable careers. Bernard Rogers (1893-1968) would soon be appointed to the Eastman School faculty, serving 41 years altogether, and becoming a prolific composer in his own right. William Quincy Porter (1897-1966) enjoyed prominence as Director of the Cleveland Institute of Music, and George F. McKay (1899-1970) went on to compose prolifically, was appointed to the University of Washington in 1927, and established that institution’s composition department. Adolph Weiss (1891-1971) doubled as an orchestral bassoonist, playing in several major orchestras during his career. Donald Tweedy (1890-1948) became a respected educator and taught at several institutions, including Vassar College, UCLA, and the Eastman School of Music. Mark Silver (1892-1965) is now something of a dark horse, but OCLC cites a few original compositions by him.

Inevitably, of the seven composers featured in the May 1st, 1925 concert, the uncontested winner in the popularity department is Aaron Copland (1900-1990), who for some time enjoyed the nickname “dean of American composers” and who became a respected mentor to composers at Tanglewood and whose works in all genres became standard repertory. The performance of Mr. Copland’s Cortège macabre was a world premiere from a planned but never realized ballet Grohg.[6] Following the May, 1925 American Composers’ Concert, Mr. Copland would make several more visits to the Eastman School and to Rochester, with later visits in (but not limited to) 1964, 1974, 1976, and 1979.

The Eastman School would continue to mount American Composers’ Concerts, always under Hanson’s direction. (After his retirement in 1964 he would continue to be involved in the capacity as Director of the newly founded Institute for American Music, the same Institute which today bears his name.) In October, 1971, the concert program of May 1st, 1925 was repeated in the Eastman Theater as part of a gala celebration of Howard Hanson’s 75th birthday. This re-creation of the first American Composers’ Concert served as the definitive conclusion to the series that Hanson had launched nearly half a century earlier. Between 1925 and 1971, the American Composers’ Concerts had presented more than 2,000 works by more than 900 composers. In 1972 the Eastman School published a complete list of the repertory programmed in the American Composers’ Concerts and the Festivals of American Music, itemizing all of the individual composition titles and specifying which performances constituted premieres. A Foreword to the booklet was provided by then-Sibley Librarian Dr. Ruth T. Watanabe.

Following the launch and early success of the American Composers’ Concerts, there were to be other initiatives in American music. In the spring of 1931, the Eastman School sponsored a four-day festival of performances of American music, marking the inauguration of a new series; the model would be repeated one year later under the name Festival of American Music, with an annual Festival occurring at the Eastman School each spring up through the year 1971. Hanson took things a step further in 1935-36 when he inaugurated the so-named Annual Symposium of American Orchestral Music (in the fall) and the Symposium of Student Works for Orchestra (in the spring). Each of the two new series underscored Hanson’s implicit preference for the orchestra as a medium of musical performance. The springtime Symposia were founded to promote the work of Eastman School composition majors, whatever their national or ethnic origin, whereas the fall Symposia were expressly tied in with his American music interests.

A comprehensive history, chronology, and analysis of the American Composers’ Concerts and the Festivals of American Music was contributed by Dr. Andrea Kalyn in her doctoral dissertation Constructing a nation’s music : Howard Hanson’s American Composer’s Concerts and Festivals of American Music, 1925-71 (University of Rochester, 2001). In the course of her research, Dr. Kalyn had been granted access to relevant primary sources at a time when they were held in private hands. Many of those same sources now reside in the Howard Hanson Collection at the Sibley Music Library.

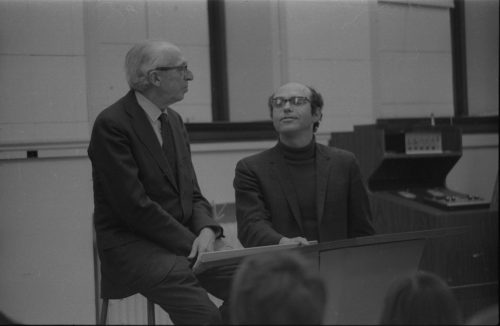

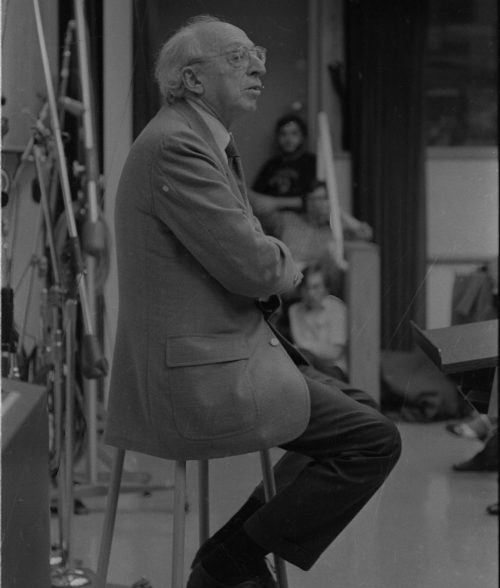

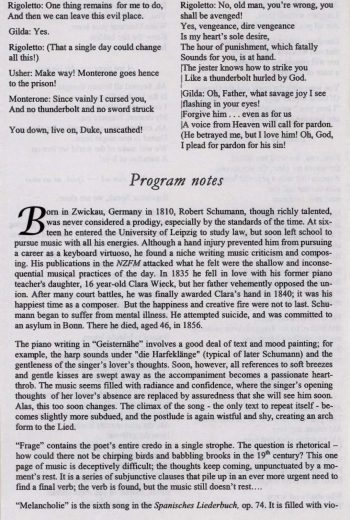

On a return visit to the Eastman School, Aaron Copland speaks to Eastman students on May 1st, 1974. ► Photos by Louis Ouzer. Master negative no. R1929-12 and R1929-22.

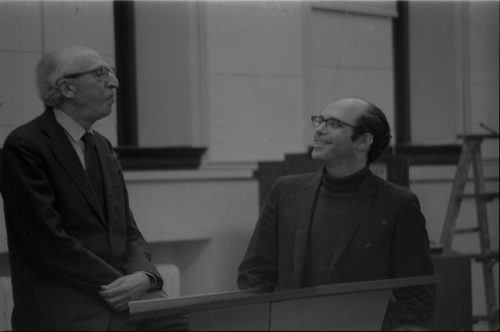

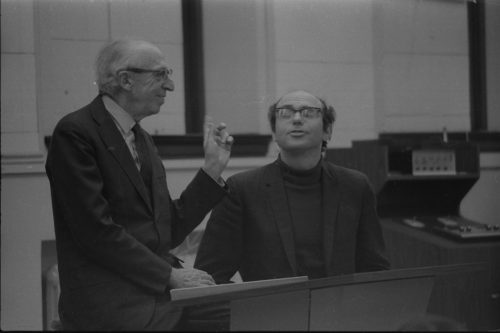

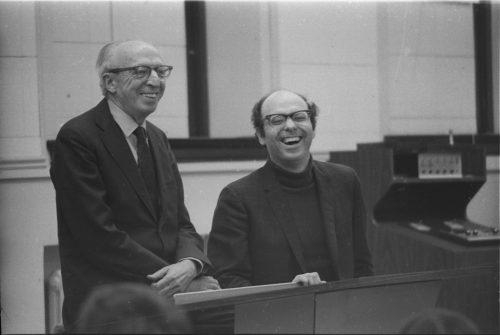

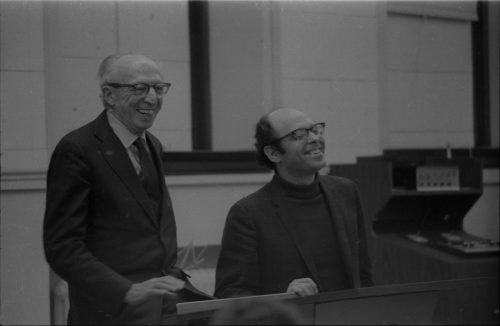

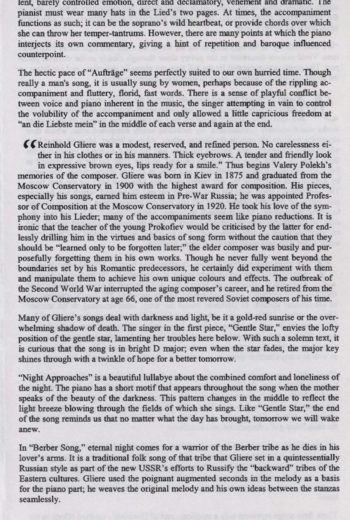

On a return visit to the Eastman School, Aaron Copland visits with fellow composer Sam Adler, May 1st, 1974. Mr. Copland had been Professor Adler’s mentor at Tanglewood in 1949 and 1950. ► Photos by Louis Ouzer. Master negative nos. R1931-2, R1931-4, R1931-5, R1931-6, R1931-7.

[1] Chapter 17, “Promoting the Cause of American Music” in The Autobiography of Howard Hanson, compiled and edited from manuscript sources by Vincent A. Lenti. Unpublished; 2013. Eastman School of Music Archives.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Copies of the articles are preserved in the Rochester Scrapbooks (Sibley Music Library) and the Howard Hanson Collection (Eastman School of Music Archives). In addressing the subject of modern music, he explicitly drew a distinction between his preferred style of music, i.e. that which engaged human emotions, and those styles that, in his view, did not. In his efforts to connect with the local audience and to engage their interest and support, Hanson took pains to cast himself as an egalitarian, more lowbrow than highbrow.

[4] Copies of many of these press articles are preserved in Hanson’s pressbooks in the Howard Hanson Collection.

[5] Mr. Downes (1886-1955) also took time to pay Sibley Music Librarian Barbara Duncan a high compliment during his Eastman School visit in 1925, leaving an appreciative inscription in the School’s guest book that ended with the words, “Long may she continue her work.” Mr. Downes and Miss Duncan were on first-name basis thereafter. Guest Book, Eastman School of Music. Eastman School of Music Archives.

[6] The synopsis for the ballet had been provided by Harold Clurman, with whom Mr. Copland had shared a flat in Paris. Some other sections of the ballet were later fashioned by Mr. Copland into his Dance Symphony, which was premiered in Philadelphia under Leopold Stokowski’s direction in 1931. Oliver Knussen conducted a revision of Grohg in London in 1992.

The Weekly Dozen

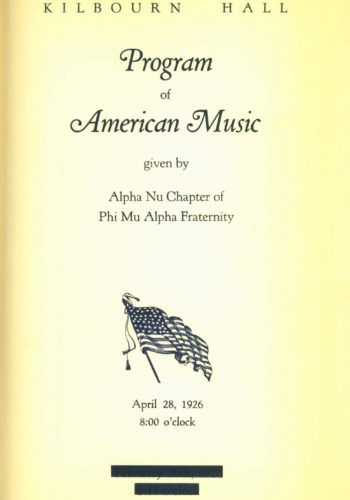

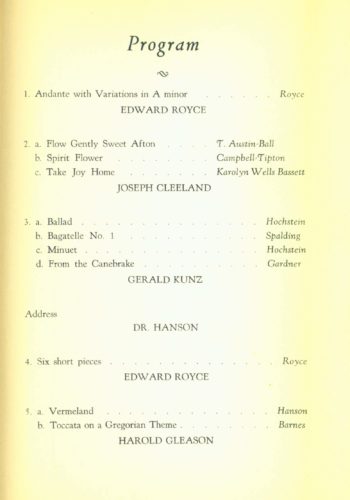

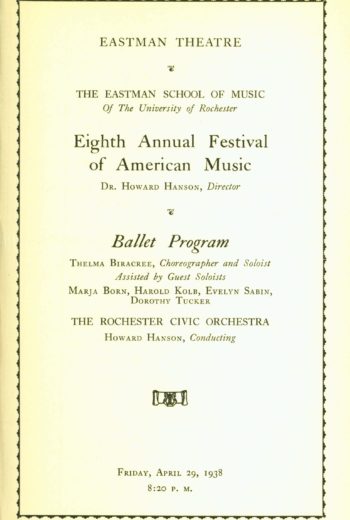

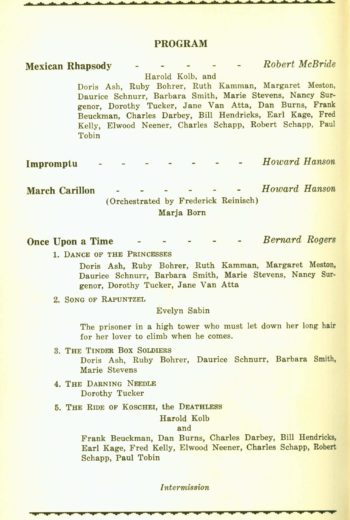

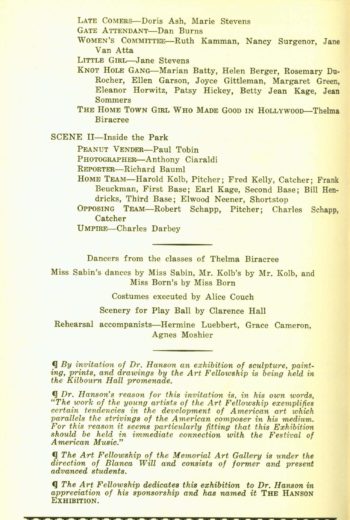

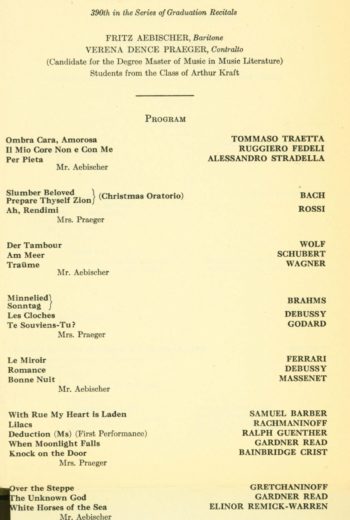

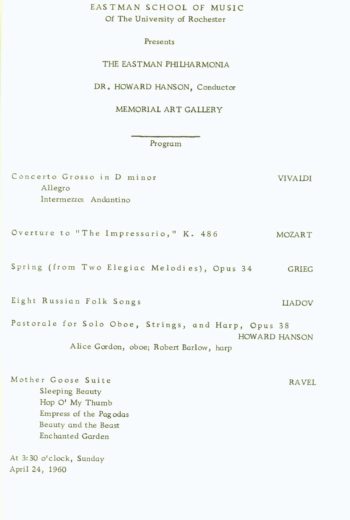

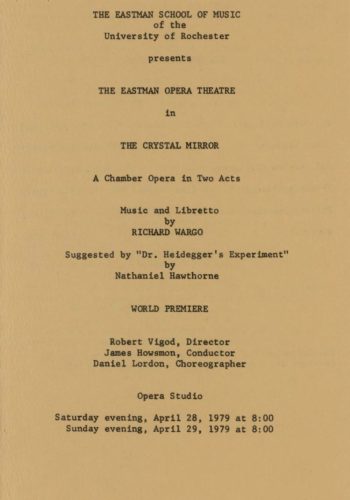

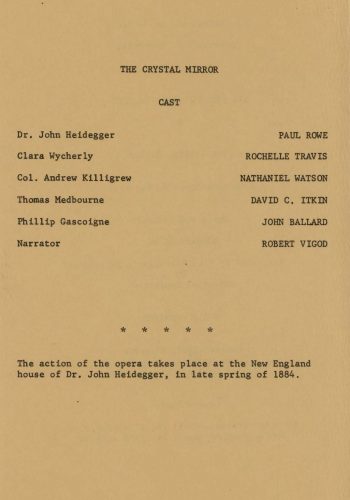

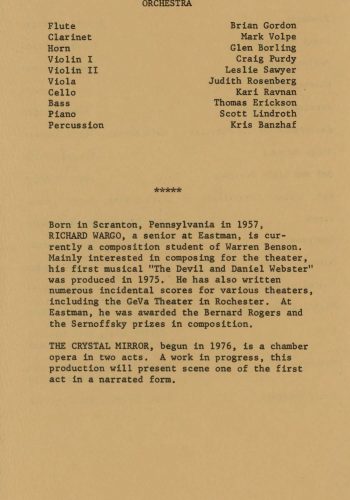

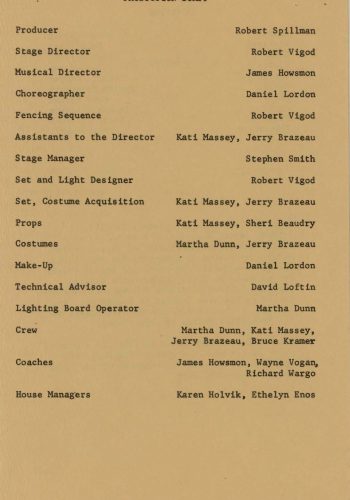

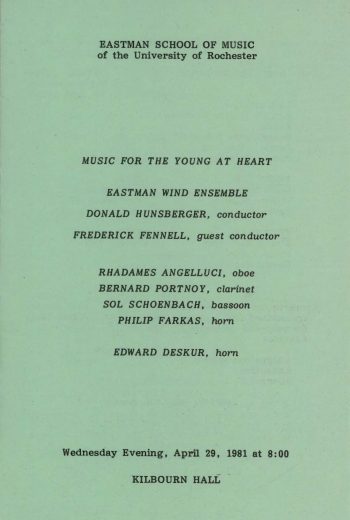

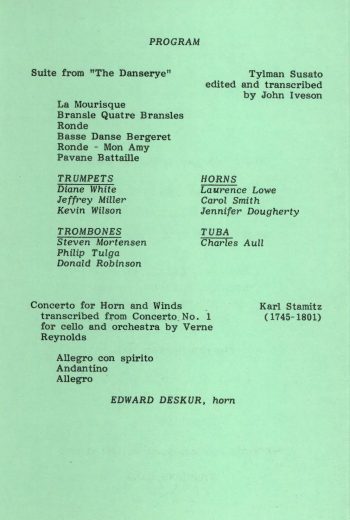

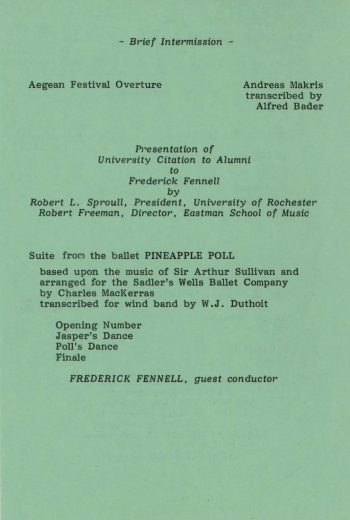

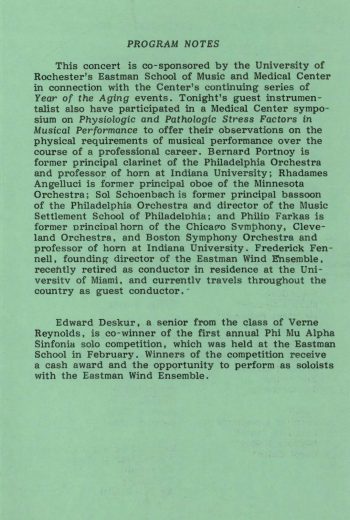

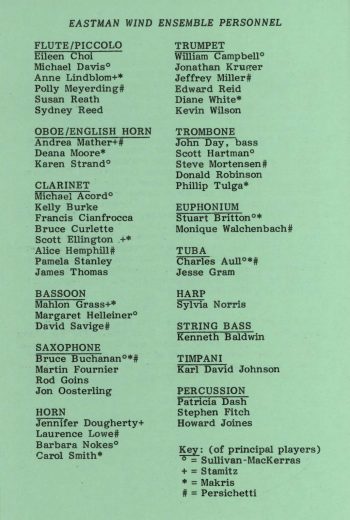

In this week’s “Weekly Dozen” we recognize a program of American music sponsored by the Eastman School’s Alpha Nu chapter of the Phi Mu Alpha fraternity (signifying that Eastman students were climbing aboard Howard Hanson’s American music bandwagon); a ballet performance from the years when dance was regularly performed in the Eastman Theater; a rousing program of marches conducted by Frederick Fennell, but this time performed by the Eastman Philharmonia and not the Eastman Wind Ensemble; a world premiere by Eastman Opera Theater of an Eastman student composer’s opera; and finally, some superlative student performances such as grace the Eastman concert calendar each week of the semester.

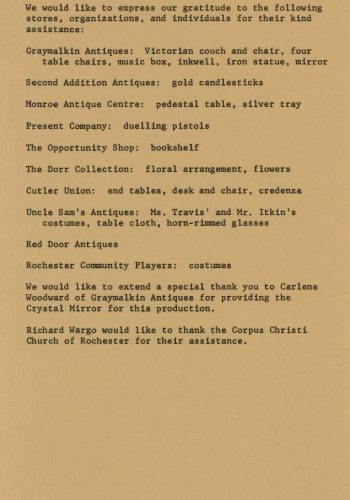

►April 28-29, 1979

►April 29, 1981

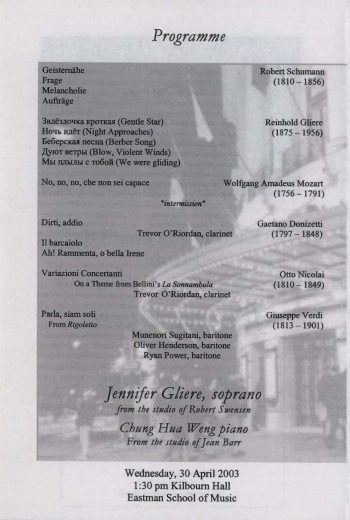

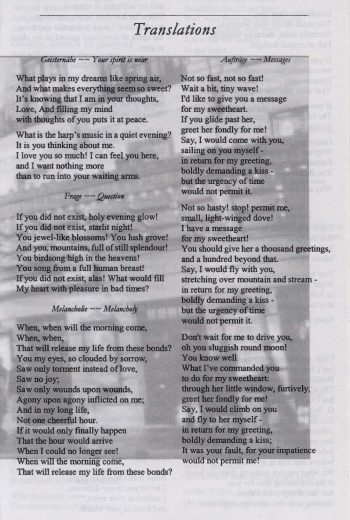

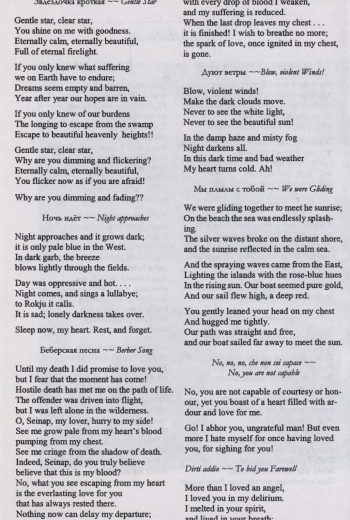

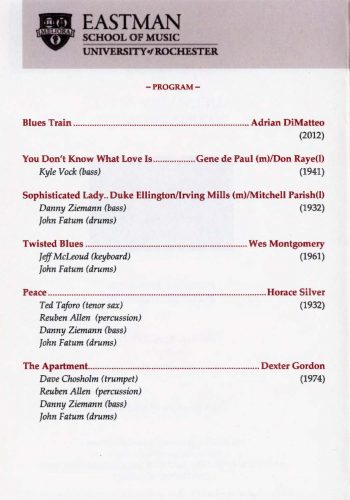

►April 30, 2003

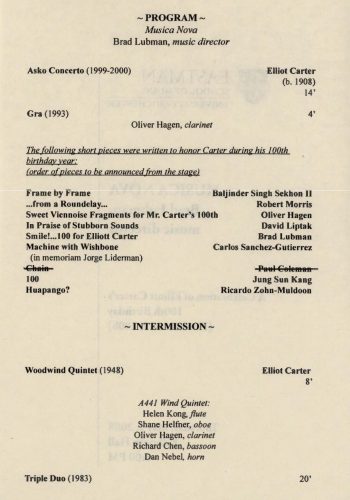

►May 1, 2008

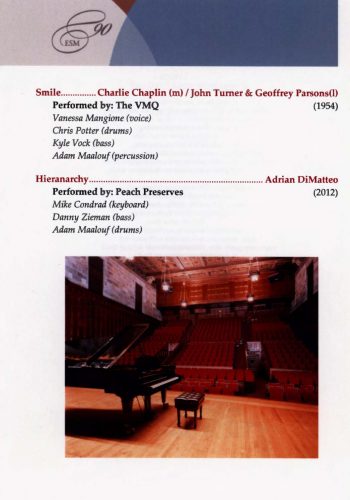

►April 29, 2012

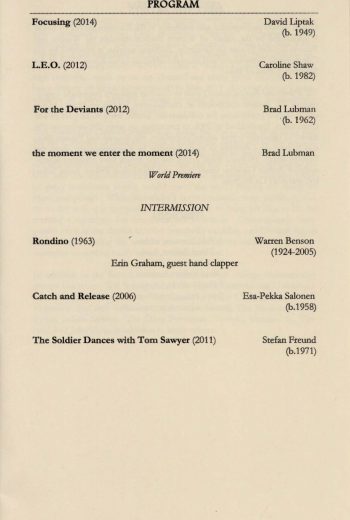

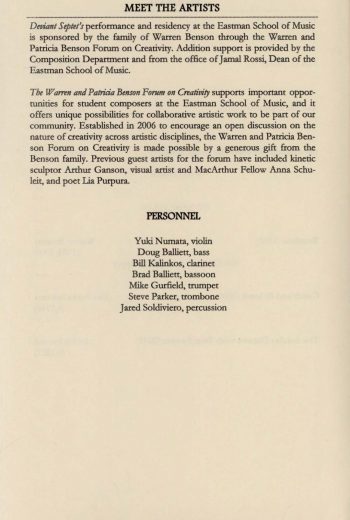

►April 30, 2016