Published on March 14th, 2022

1972: Rudolf Serkin engagement at Eastman

Fifty years ago this week, beloved concert pianist Rudolf Serkin made a guest appearance at the Eastman School that included a Kilbourn Hall master class and an Eastman Theater solo recital. Mr. Serkin’s appearance was the third of the designated Fiftieth Anniversary Concerts, a sequence of four guest appearances by internationally renowned artists during the Eastman School’s 1971-72 Fiftieth Anniversary Festival. (Altogether, those four artists were Henryk Szering, Vladimir Ashkenazy, Mr. Serkin, and Isaac Stern; each man’s Eastman appearance included both master class and recital.) At the time of his Eastman School visit, Mr. Serkin was nearing age 69, and in that very same month, he marked his 100th appearance with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra by performing the Brahms First Concerto with the orchestra.

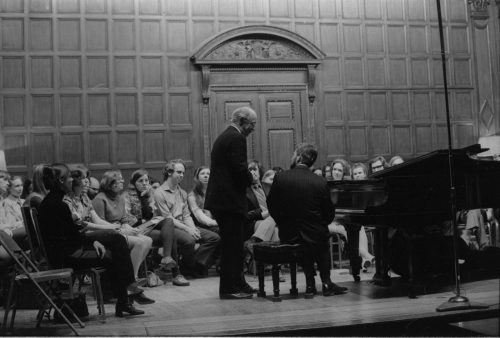

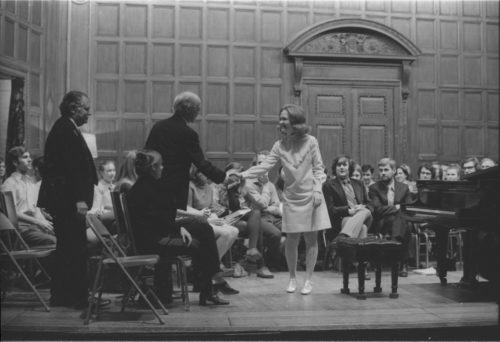

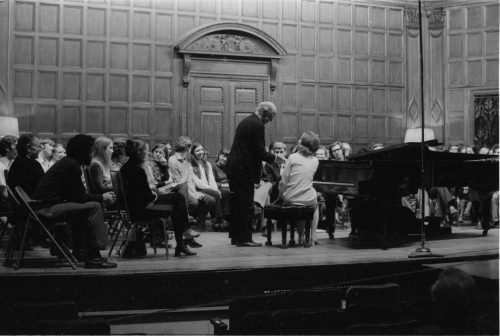

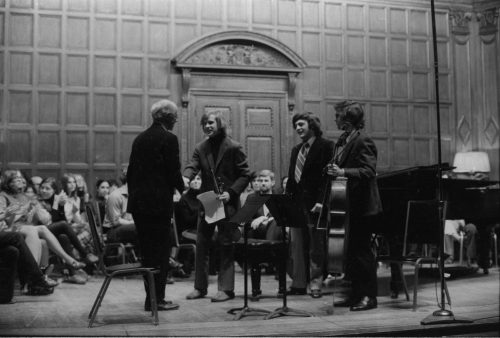

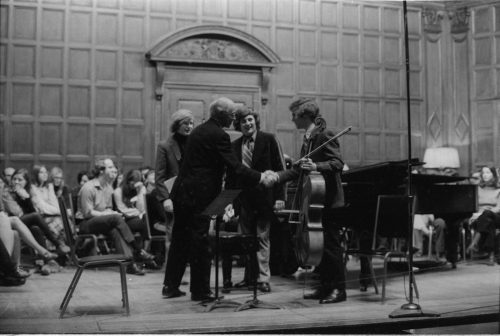

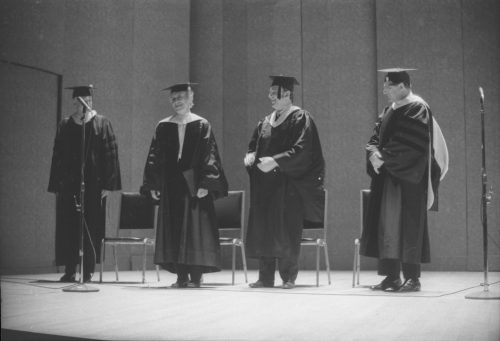

Guest artist Rudolf Serkin in master class with Eastman School students on the stage of Kilbourn Hall. At the end of the class, Professor Eugene List presents Mr. Serkin with some tokens of appreciation. R1469-4; R1469-5; R1469-6; R1469-8; R1469-9; R1469-11; R1469-12; R1469-13; R1469-15; R1469-16; R1469-17; R1469-18; R1469-19; R1469-20; R1469-21; R1469-22

Just as now, during our on-going Centennial celebration, the Fiftieth Anniversary Festival was an extended celebration when the Eastman School pulled out the proverbial stops to showcase the school’s many strengths and to reflect upon the numerous contributions made by the Eastman School to the larger musical world. The 1971-72 year included the gala re-opening in January, 1972 of the Eastman Theater (with live simulcast via WXXI-TV) following several months of extensive renovations. The Festival also included the four above-mentioned Fiftieth Anniversary Concerts and also a Great Performers Series that featured other distinguished guest artists and Eastman School faculty members in recital. There were also four large Symposia throughout the academic year, one Symposium lasting five days and drawing an international body of attendees, and each one examining and discussing issues of relevance in the modern musical world, namely, music criticism, music education, musicology, and [support of the arts]; each of the four Symposia drew an international body of attendance. Previously in “This Week at Eastman” I’ve mentioned (in the week of February 7th/13th) the Symposium on music education, at which the distinguished presenters included Shinichi Suzuki. (That Symposium happened to be named the Symposium on Music Teaching and Learning, which might be said to have presciently foreshadowed the future name change of the Eastman School’s Department of Music Education.) And finally, there were the premiere performances in fulfillment of the commissions of new works; altogether, the Eastman School had commissioned a total of 23 new musical works. The premiere performances created showcase opportunities for Eastman School ensembles, at times involving collaboration with distinguished guest soloists. In short, the Fiftieth Anniversary Festival was not to be missed.

Mr. Serkin’s illustrious, inspiring life and career require no introduction here, but I think it pertinent to underscore his roles in both teaching and chamber music. At the time of his Eastman appearance, Mr. Serkin was still serving on the faculty of the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, where he had taught since 1939, and where he had served as Director since 1968. His students over the years had included such pianistic luminaries as Eugene Istomin and Richard Goode. Mr. Serkin was also one of the founders of the Marlboro Music School and Festival in Vermont, together with his longtime colleague and friend Adolf Busch and the Moyse family trio of Marcel, Louis, and Blanche Moyse. Following the death of Mr. Busch in 1952, Mr. Serkin devoted a huge amount of his personal time and energy to developing and nurturing the annual Marlboro Festival, effectively becoming its guiding light and inspiration. The annual Festival, lasting seven weeks each summer, has left a huge imprint on chamber music in the United States. The renowned Guarneri Quartet, whose 1972 Eastman appearance I mentioned in last week’s entry, was formed at the Marlboro Festival in 1964. Pianist Emanuel Ax, whose Eastman master class I mentioned in the entry for the week of February 28th/March 6th, first performed in collaboration with Yo-Yo Ma, who would become his longtime duo partner, at the Marlboro Festival in 1973. Numerous other such instances of longtime collaboration and inspired performance have emerged from the unique environment that is Marlboro, and for the better part of four decades, Marlboro bore Mr. Serkin’s indelible imprint .

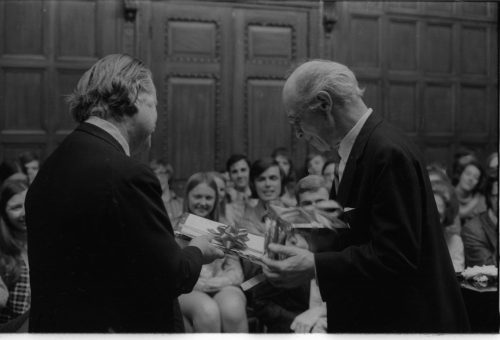

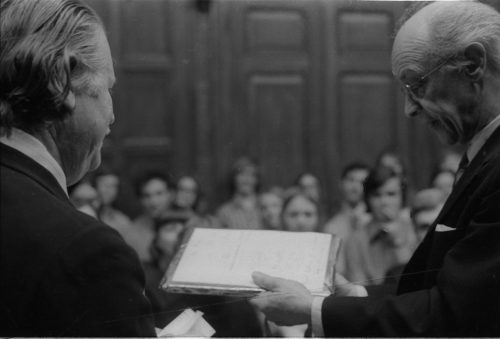

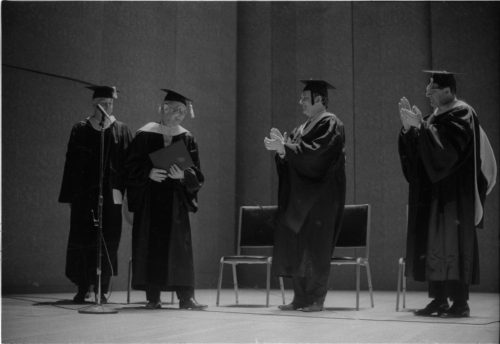

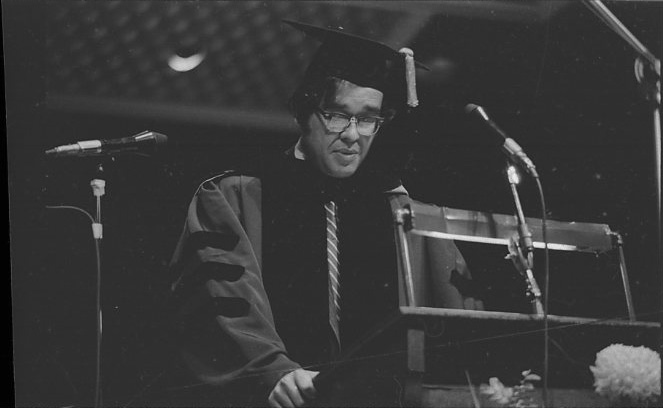

Mr. Serkin’s Eastman recital was an all-Beethoven program, comprised of four Sonatas: the Pathétique in C minor, opus 13; the Sonata in E major, opus 109, one of the five last Sonatas; the Sonata no. 2 in F major from opus 10; and the stormy Appassionata in F minor, opus 57. (! You can interact with a first edition of the opus 57 at the Sibley Music Library’s Ruth T. Watanabe Special Collections.) The choice of Beethoven was entirely in character for Mr. Serkin, who was widely regarded as one of the 20th century’s foremost interpreters of Beethoven. At the conclusion of the recital, Mr. Serkin graciously accepted an honorary Doctor of Music degree from the University of Rochester. UR President W. Allen Wallis presided over the short ceremony, at which Eastman School Director Walter Hendl presented the degree and read the citation, and Assistant Director Daniel Patrylak, BM ’54, MM ’60, hooded the newly designated Dr. Serkin. The citation which Mr. Hendl read to the audience is worth quoting here in its entirety:

“Few musicians can emulate, and none can hope to excel the career of Rudolf Serkin, celebrated concert pianist, noted teacher, Director of the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, President and Artistic Director of the Marlboro School of Music, part-time farmer in Guildford (Vermont), and father of a talented family.

“Born in Eger, Bohemia, Rudolf Serkin was educated in Vienna during those years when it was the cultural capital of the world, and there he came to know intimately both the traditional and the avant-garde in music. He made his debut with the Vienna Symphony at the age of twelve. Five years later, under the aegis of Adolf Busch, he began his remarkable concert career, first appearing in America in 1933. Each year he tours the United States, his adopted country, and he plays frequently in Europe, South America, Iceland, Israel, and the Orient.

“Hailed as one of our most profound, sincere, and magnetic interpreters, Rudolf Serkin is an inspiration to thousands of listeners and students. Unselfishly dedicated to the benefit of others, he has been a member of the Carnegie Commission on Educational Television and is now Vice-President of Young Audiences. For his outstanding service in the cause of good music, President Kennedy honored him with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.”

Conferral of the honorary Doctor of Music degree on guest artist Rudolf Serkin. UR President W. Allen Wallis presides; Director Walter Hendl presents the degree and reads the citation; and Assistant Director Daniel R. Patrylak hoods the newly designated Dr. Serkin. R1471-8; R1471-10; R1471-11; R1471- 14

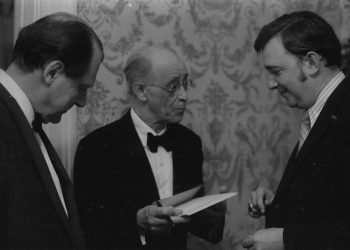

As was typical of key events in that eventful 50th anniversary year, photographer Louis Ouzer enjoyed considerable freedom of movement during the Serkin visit, enabling him to photograph Mr. Serkin and others in candid moments. Several of his shots from the Serkin visit are displayed here, in which we see Mr. Serkin being escorted into the Eastman School by Professor Eugene List; Mr. Serkin interacting with Eastman School students on the stage of Kilbourn Hall, their evident joy in the interaction radiating from their faces; Mr. Serkin standing alone on-stage in the Eastman Theater, a venue where by the 1970s a solo piano recital was decidedly the exception and not the norm; Mr. Serkin acknowledged and hooded as he received his honorary doctorate; and finally, Mr. Serkin among other guests at the post-concert reception hosted by Mr. and Mrs. Hendl at Hutchison House. It seems safe to say that the Eastman School welcomed Mr. Serkin with open arms and was left the better for his having visited.

! Calling Eastman School alumni! If any one of you sees yourself in any of these photographs, please email me!

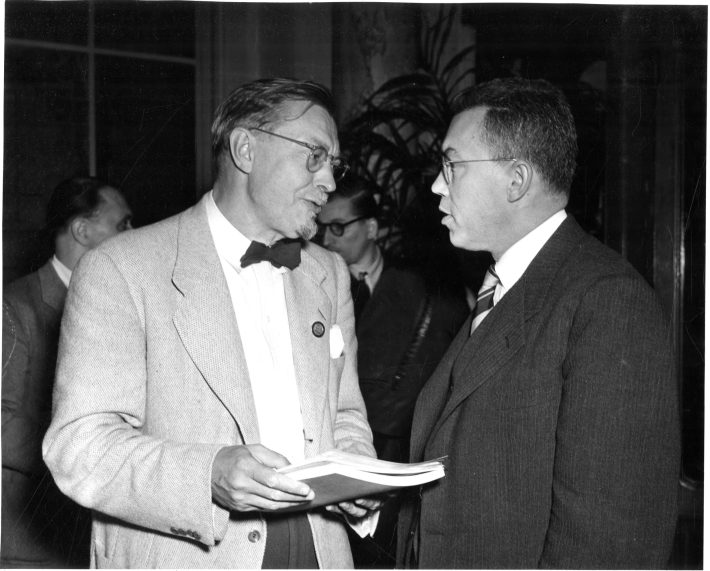

Guest artist Rudolf Serkin in conversation with Eastman School Director Walter Hendl at the post-concert reception hosted by Director and Mrs. Hendl at Hutchison House. The two men shared more than one professional experience in common; they were both performing artists; they were both Directors of professional schools of music. R1470-2; R1470-6; R1469-9; R1469-35; R1469-36

Guest artist Rudolf Serkin obliges Eastman School Assistant Director Daniel Patrylak with an autograph. R1470-10; R1470-11

Director and Mrs. Hendl share pleasantries and conversation with guest artist Rudolf Serkin and his wife, Irene Busch Serkin. R1470-27; R1470-28

1999: The Archive of publisher Carl Fischer, LLC at the Sibley Music Library

Twenty-three years ago this week, with the delivery of a vast collection on March 18th, 1999, the Sibley Music Library entered into a unique relationship with music publisher Carl Fischer, LLC. The Eastman School of Music and publisher Carl Fischer had actually maintained a commercial relationship that dated back to the 1930s, but I consider the initiative between the Sibley Music Library and Carl Fischer a wholly unique venture between a corporate entity and a research library. I also think it safe to say neither side foresaw in 1999 the scale of outside interest in what we were launching.

Carl Fischer, LLC

Carl Fischer, LLC is one of the oldest and most prosperous music publishers in the USA. Its founder, Carl Fischer, born in Germany in 1849, was by trade a manufacturer of musical instruments; in 1872 he emigrated to New York City, where he opened a musical instrument shop at 79 East 4th Street. Recognizing the need for musical arrangements for the diverse range of ensembles prevalent at that time, he began to reproduce—with permission—music in longhand, eventually adopting lithography as his working medium. This activity was so successful that by 1880 he found it necessary to move to larger quarters, and from then on pursued the dual objectives of selling instruments and publishing music. The company sought to provide music according to the varied tastes and styles of that day, including the increasing appetite for band music, and on that front, the company became the principal publisher of such figures as Arthur Pryor, John Philip Sousa, and Henry Fillmore. To a great extent, development of the company’s band catalogue was shaped by the renowned Edwin Franko Goldman, who had joined the company’s staff and was himself an eminent band director. Other initiatives included publishing instrumental music for silent film accompaniment, and music for school use, serving both instruction and performance. The company’s concentration on materials for music education continues to this day.

Carl Fischer died in 1923, at which time his son Walter S. Fischer assumed leadership of the company. In that same year construction of a 12-floor building at 56-62 Cooper Square was completed; the firm would do business in those new quarters from 1923 until early 1999. A retail store operated on the ground floor, and the upper floors were home to a sizable warehouse and other facilities, including studios for musical instruction. In 1927, the company opened its vast Rental Library, which has remained to this day a substantial operation providing performing materials for large ensembles. (It is joined to the Rental Library of the Theodore Presser Company, which in 2004 became Carl Fischer’s sister company.)

Walter Fischer died in 1946, and his son-in-law Frank Hayden Connor became president of the company. In those years immediately following World War II, Mr. Connor re-established contact with major European publishers and thereby extended the company’s activities both domestically and internationally. In the United States, Carl Fischer came to represent numerous UK-based and European publishing houses; it also became the sole selling agent for several U.S.-based publishing houses and other entities besides, including the Eastman School of Music.

The Carl Fischer imprint is ubiquitous. Probably no music student in the United States can avoid using any of Carl Fischer publications at some point during his or her studies. Those who work in music libraries are in daily contact with Carl Fischer’s publications in their stacks; professionals with ties to the music publishing community are well acquainted with the company’s broad hegemony throughout the industry. As the company was nearing its centennial, the company’s history was concisely documented by Susana F. Herz in her article “The Carl Fischer Centennial,” published in the Music Educators’ Journal in 1972. (The article’s publication in that particular journal was itself an indication of the company’s traditionally strong emphasis on pedagogical and teaching materials.) Where the company’s publishing program is concerned, the Carl Fischer catalogue has always represented a vast compendium of music editions, arrangements, and methods—in short, everything for the student musician, for the professional, and for ensembles of various sizes and configurations, including an immense band catalogue, traditional and contemporary orchestral and choral repertoire, educational materials, and solo and ensemble music in every musical style. In recent years the catalog has changed, most tangibly in that the standard performing literature has been allowed to go out of print, but the company’s attention to teaching materials has remained strong.

The Sibley Music Library

The other player in the story is the Sibley Music Library at the Eastman School of Music. The SML brought two interests to the table in 1999, the first being a serious regard for the Eastman School’s historic relationship with Carl Fischer and the latter’s status as sole selling agent for a series of Eastman Publications. That series of publications included many compositions by Eastman School-affiliated composers, faculty members and alumni, including such names as Howard Hanson, Wayne Barlow, Warren Benson, John La Montaine, and others. Correspondence archived in both the Carl Fischer archive and the Howard Hanson Papers at the Sibley Music Library reveals continuing good will on the part of both parties.

The SML’s other interest was a concern for the history of music publishing, which had been articulated as one element of the library’s mission under the direction of Mary Wallace Davidson (Librarian, 1984-99). The first substantial manifestation of that interest was a gift of archival materials from publisher David K. Sengstack, received in October, 1991. David Sengstack made his gift as part of an overall design to establish a critical mass of publishers’ archives at the Sibley Music Library under the name the John F. Sengstack Archives of Music Publishing, with the Sengstack materials constituting the seed collection. The underlying concern was that, as the smaller music publishers in the U.S. are acquired by large conglomerates, information on the history of music publishing in the U.S. is being relegated to warehouses and, ultimately, discarded and forever lost. The Sengstack vision was that the Sibley Music Library should mount a concerted effort to collect and archive historical information from music publishers currently active, or, in the words of the Agreement document signed by officers of the David K. Sengstack Foundation and the Sibley Music Library, “. . . to establish within the Sibley Music Library and maintain in perpetuity an archival collection of music publishing records to be used for scholarship purposes.” To that end, the David K. Sengstack made a financial contribution to provide for the acquisition of other publishers’ archival materials, and to assist in the establishment and initial operation and growth of the John K. Sengstack Archives of Music Publishing.

The second component of publisher David Sengstack’s gift to the SML was the archive of papers of the Birch Tree Group, Ltd. The Birch Tree Group had its roots in the activities of David’s father, John F. Sengstack (1893-1970), himself a major player in American music publishing. The elder Sengstack had purchased and reorganized the Clayton F. Summy Company (Chicago) in 1925, and later served as general manager of the Theodore Presser Co. from 1928 until 1931. In 1957 he purchased C. C. Birchard & Co.; his enterprise subsequently operated under the name Summy-Birchard Publishing Company. In 1958 his son David became president of Summy-Birchard; David soon acquired a number of other publishers, including the stock and archives of the Arthur P. Schmidt Company, a highly-respected firm that operated in Boston between 1876 and 1959. (I should mention that the Arthur P. Schmidt Company bore the distinction of being the first US music publisher to issue a symphony composed by a native-born American composer (to wit, John Knowles Paine’s Symphony no. 2 (“In the Spring”), composed in 1879 and published by A. P. Schmidt in 1880.) In 1979 David Sengstack formed the Birch Tree Group, Ltd. as a holding company for all of his business interests, and in 1991 made a gift to the SML of the Birch Tree Group’s assembled archival records. Among the most noteworthy holdings of the collection is the cumulative stock of last copies of printed music issued by the Arthur P. Schmidt Company (Boston). A detailed finding aid (inventory) of the Archive of the Birch Tree Group, Ltd is accessible at the SML website at URL: https://www.esm.rochester.edu/sibley/files/Birch-Tree-Group-Ltd.pdf

Thus, in 1991 the Sibley Music Library launched an initiative in which its Special Collections unit would be the chief repository of content. The initiative to preserve the records of U.S. music publishing has been comprised of several components. Following the Sengstack gift in 1991, there was discussion in 1992 and again in 2000 of acquiring the archive of the Theodore Presser Company. (That archive was eventually given over to the custody of the Library of Congress.) In addition, monies from the Sengstack contribution have funded the purchase of several publishing-specific items for the library’s general and reference stacks; other items have been purchased for the Sibley vault. However, the single largest element in the initiative to date was taking custody of the Carl Fischer Archive. It was precisely on account of the Sengstack initiative that the SML received the news of the Carl Fischer Archive’s availability in early 1999 with both keen interest and a very real concern for the preservation of so large a segment of the documentary record of U.S. music publishing.

The Carl Fischer Archive

At the beginning of 1999, corporate changes were underway at Carl Fischer Sandy Feldstein had just become president, embarking on a mission to modernize the company’s operations. The corporate office was to be relocated from the company’s eminently recognizable renowned Cooper Square building (see photo displayed here) to smaller quarters in Manhattan, and accordingly, the warehousing operation and the Rental Library would be relocated to Paoli, Pennsylvania. The company’s archive, stored in one room on the building’s sixth floor, had yet to be fully addressed. And precise here is where the Sibley Music Library enters.

One morning in early February, 1999, Jim Ripley, a doctoral student in conducting [later Ph.D. 1999, and now serving as Director of Instrumental Activities for Carthage College, Kenosha, Wisconsin], was searching for performance materials for Howard Hanson’s epic composition Pan and the Priest. Jim contacted Carl Fischer’s managing editor and also the company’s rental library, and he was informed that if the parts were available, they would be in the company’s Archive — which, the rental officer added incidentally, was likely going to be disposed of due to the company’s impending move. From that moment, things happened quickly. Jim spoke to his advisor, Professor of Conducting and Ensembles Dr. Donald Hunsberger, who immediately contacted SML Head Librarian Mary Wallace Davidson. Mrs. Davidson’s ardent professional interest in music publishers was awakened, and she promptly scheduled a trip to New York City to survey and assess the Archive. Three weeks later, a gang of four of us—Mrs. Davidson, myself, and graduate students Seth Brodsky and Ian Quinn—set out in Mrs. Davidson’s station wagon on a spring break outing to Manhattan to pack up the Carl Fischer archive.

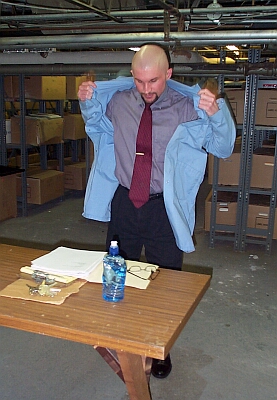

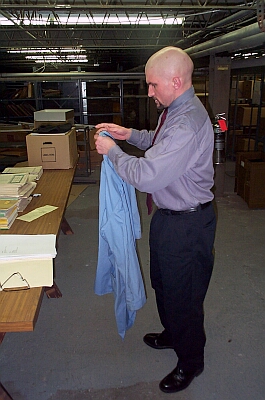

► Photos by Mary Wallace Davidson, March 1999:

Nearing the end of their week’s work, team members Brodsky, Coppen and Quinn are seen among the lines of shipping crates that they have filled and have lined up in sequence in the space that had previously housed Carl Ficher’s Rental Library. The shipping crates (some 400 in all) would be trucked to Rochester in the following week.

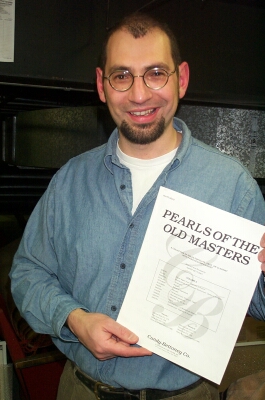

The trip down to Manhattan was not without incident. As we were motoring down a hilly rural route upstate, Mrs. Davidson was pulled over by an instantly materializing New York State trooper and was issued a speeding ticket. Four hours later, just when we had arrived in Manhattan, an MTA bus kissed one of the back doors of Mrs. Davidson’s vehicle; Ian Quinn was mere inches away from injury but was fortunately unharmed. The vehicle was towed away for repairs and we four resolved to brush off the events of the drive. Awakening the next morning, we all made our way to Cooper Square from our respective accommodations—Mary had booked herself and me in at the Gramercy Park Hotel, which was within walking distance—and over the course of four 12-hour days, we four packed up the company’s extensive Archive, fueled by frequent cups of Starbuck’s coffee and replenished with delicious ethnic cuisine during our lunch and dinner breaks. The result of the week’s work? A tidy sequence of 391 shipping crates, each packed to capacity with precious archival content, and described by Ian in an Excel spreadsheet as he walked along the rows of crates with laptop computer in hand. The 391 crates were trucked to Rochester the following week, and were delivered to the “old” Sibley Music Library building while Mrs. Davidson and I were both attending the annual conference of the Music Library Association in Los Angeles. Several days later, Mr. Lauren Keiser, until that time Executive VP of Carl Fischer and now the company’s in-coming President, flew up to Rochester bringing five additional boxes of documents, these mainly consisting of papers from the President’s Office. News of the Archive’s transfer was published in the summer, 1999 issue of Eastman Notes, accompanied by a photograph of the four of us (displayed here). A Loan Agreement was quickly concluded, and was signed by representatives of Carl Fischer, LLC and the Sibley Music Library on April 13th and April 22nd, 1999.

An Archive comprised of 391 shipping crates’s worth of material is a hefty bundle of content. Apart from the sheer extent of the Archive, there would be the need of adequate working space and infra-structure to process the holdings so as to get them into their research-ready state. Mrs. Davidson pointed to the one space on the Eastman School campus that could possibly accommodate such a large collection: the basement of the “old” Sibley Music Library building on Swan Street. An article could be written about that building alone. When constructed in 1937, it was promoted at that time as being the first building ever yet constructed in the United States exclusively for a music library. Former Head Librarian Ruth T. Watanabe (served 1947-84) once described the “old” Sibley Music Library as standing “in unassuming modesty” behind the more elegant Eastman School and Eastman Theater. Truly, Ruth was being characteristically tactful; her predecessor Barbara Duncan (served 1922-47), a pragmatic German-American Bostonian who did not mince her words, cut to the chase when telling a collection donor in 1942 that the Depression-era building had been built plain because there was no money with which to make it fancy. Nevertheless, the building boasted an extensive basement that, in spite of many low-hanging beams and conduits, would offer us the floor space and shelving that we needed for the Archive. There was, in fact, a precedent here, for by the 1970s members of the SML staff had resorted to storing materials in the basement when the library’s collections were threatening to surpass the building’s capacity at ground level and above. It was striking to me to think that the “old” building was once again being pressed into service for current SML business.

When you come down to it, a publisher carries out an enormous amount of activity. The publisher negotiates and contracts with authors so as to obtain original works to publish (and acquires those works in some format—back in the day ink on paper, but today in entirely digital formats); the publisher prepares said works to go to press, and this editorial/production stage can be quite extensive, involving much dialogue between editorial/production team and the author. The work eventually goes to press—many publishers off-load the actual printing—but when the new publication comes back, it needs to be marketed and sold, and it also behooves a publisher to retain a library or archive of one copy of every item it has published. Some music publishers also retain rental libraries of scores that are loaned out for performance, rather than old as individual copies. This would all come into focus as we opened the shipping crates and got to work.

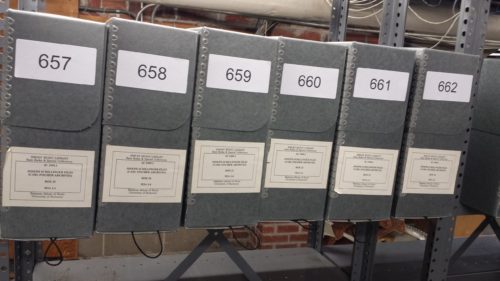

The archive was initially comprised of three distinct sub-groups: corporate papers; last copies of publications; and production packages, which were comprised of bundles of camera-ready pages and proof copies. To these three sub-groups a fourth was later added: New Publications, comprised of two copies of each new item rolling off the press as of the fall of 2000.

For historical purposes, I regarded the corporate papers as the richest. They held general correspondence; files from the President’s office; sales ledgers and trade catalogs; numerous commemorative documents, including anniversary brochures, scrapbooks, and photographs; sales records; editorial and publication-related correspondence; and a small amount of artwork marked up for production use. The files of editorial correspondence, arranged by surname of composer or arranger, read like a Who’s Who of American Music in the 20th-century: Howard Hanson, Roy Harris, Aaron Copland, and many others. Some of those files held fair copies in the hands of their respective composers. The sub-group of production packages contained proof copies and camera-ready masters; the proofs bore notes and annotations in the hands of members of the production team, as reflected standard procedure in publishing houses.

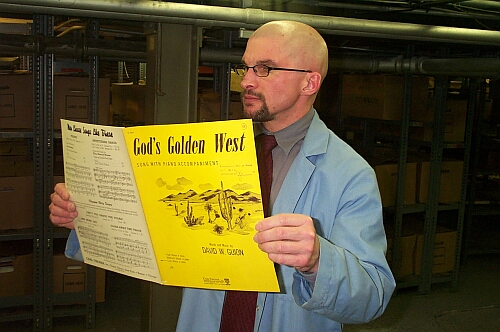

The sub-group of last copies was comprised of one copy of most of the company’s permanently out-of-print publications; not quite every publication, but certainly most of them. They were filed by their series numbers within the company’s catalogue, and each instrumental area formed its own series (J for band, CM for choral octavos, P for piano, V for solo voice, and so on). For applied musicians the world over, the last copies would prove to be a very rich source, as I’ll mention momentarily.

Arrangement and description project

Virtually as soon as word had gone out that the archive had arrived at Eastman, I began to receive inquiries from interested parties seeking copies of the out-of-print music, or else seeking historical information for articles and academic writings. The loan agreement enacted by Carl Fischer and the Sibley Music Library gave the SML permission to process the Archive according to the standards of sound archival practice, and I recognized that it would behoove us to process the archive as soon as possible so as to respond to requests in an efficient and timely manner. Owing to various workplace and workflow realities, I was obliged to defer any plans to process the Archive for some time. In March, 1999 I had only just assumed my position, and I had a good deal of work to do on the Eastman front before I could reasonably devote the time necessary to addressing the Carl Fischer Archive, but it also held a place on the to-do list.

News of the Archive’s deposit at Eastman was circulated to the extended Eastman School community in the summer, 1999 issue of Eastman Notes, and had earlier been circulated in the April, 1999 issue of The Sibley Muse. Publicly, I presented on the SML/CF archival venture in the Archives Roundtable of the Music Library Association at the MLA’s 2002 annual conference. After processing of the archive had commenced, I delivered a revised version of the presentation at the 2004 Lake Ontario Archives Conference (now the New York Archives Conference) and at the 2004 annual meeting of the New York State/Ontario chapter of the Music Library Association.

In the fall of 2002, after tracking the patterns of use over the course the first three calendar years that we’d had custody of the Archive, I consulted with a veteran university archivist from another institution who provided much valuable guidance. In the spring of 2003, after much planning, I hired and trained a team of student workers, and the processing began that June after the end of the academic year. Quite providentially, and what truly was a significant advantage, David Sengstack’s gift money provided the funds for compensating the student workers and for purchasing needed archival supplies for the project after Carl Fischer had provided us with a sum of funds for the initial materials order.

The processing project was divided into two phases: arrangement, during which the holdings were sorted, weeded, and rehoused in proper archival housing; and description, during which relevant data for each and every item were transcribed into an Excel spreadsheet. (Excel was the tool of choice owing to that being Carl Fischer’s own in-house tool.) Each of Carl Fischer’s publishing series featured a different physical format, and therefore the publications in each series posed different considerations as regards their physical arrangement and preservation. In advance of launching the project I had drawn up guidelines and plans intended to instruct the students on every last situation that I thought might arise, but notwithstanding those carefully laid plans, the arrangement phase of the project continually turned up instances that required creative solution-seeking. The student workers worked on the sub-group of last copies over the course of four summers (2003 through 2006 inclusive), after which the holdings had been properly ordered, rehoused, and described in the spreadsheet. To give an explicit idea of how many items the last copies represented, the spreadsheet ran to a total of 45,531 rows. Processing of the historical papers would continue at a slower pace during the next several academic years, and on completion, we had a finding aid (i.e. inventory) in MS Word format numbering 144 pages.

► Photos by Gerry Szymanski, April, 2003:

Streams of activity

There were four distinct streams of activity stemming from the archive, the first being the provision of reference and research service to inquirers with questions. In addition, some holdings of the Archive were perused for various scholarly ends, leading to citation in publications. Several researchers did, in fact, travel from long-distance to interact with the Archive. Copyright restrictions did apply, of course, as did the company’s proprietary interests in the Archive, and the company’s permission was a pre-requisite for any research use.

A second activity was the provision of photocopies (and later, from 2009 onwards, of digital scans) of publications to the company, typically for reissue. In this fashion Carl Fischer brought back into print numerous compositions, transcriptions, and arrangements by such renowned 20th-century greats as Leopold Godowsky, Fritz Kreisler, and Alexander Siloti. And third, the archiving of current publications was a component of the archival operation since the fall of 2000, whereby Carl Fischer sent two copies of each new publication for archiving. In time some new accessions actually went out of print and became source copies for the archival reprint service.

The fourth, and by far the largest, stream of activity was the archival reprint service, representing a unique collaborative venture between a corporate entity and a not-for profit research library, whereby individual items of out-of-print music were photocopied on demand and sold. That service amply demonstrated the inestimable value of the archive’s last copies sub-group. The origin of the service lay in the various inquiries that began to arrive after the initial dissemination of news of the Archive’s arrival at Eastman. Those requests were handled at on an ad hoc basis, with no charges levied other than the company’s standard fee for copyright clearance, but in time, the increase in the number of requests prompted President and CEO Mr. Keiser to propose a formal retailing service as a means of responding profitably to those requests. Under the scheme, the sharing of revenues was a 60/40 split, with the company retaining the slightly greater amount (the company was obliged to pay royalties, after all). For each music request, Carl Fischer’s New York City office invoiced the customer; the Sibley Music Library then generated and sent the authorized photocopies directly to the customer. The archival reprint service was advertised in Carl Fischer’s annual trade catalogues and on the company’s website. In addition, news of the service was circulated via numerous electronic listservs, and, what was probably equally as effective, via word-of-mouth. Carl Fischer’s dealers regularly referred customers to Eastman with requests for the permanently out-of-print (POP) titles. On average I used to receive approximately one dozen inquiries after POP titles each week, with approximately half of those resulting in completed transactions.

Under the provisions of the archival reprint service, we provided music to customers in all parts of the U.S. and throughout Canada and Europe, and eventually to customers in various locations in the Far East. The customer pool included band directors, solo performers (both professionals and amateurs), school music teachers, choir directors, and retail music dealers who were making purchases on behalf of their customers. Authorized photocopies were purchased for use in ensemble concerts both large and small; in religious services of various denominations; for home music-making; for teaching and pedagogical purposes; and for civic use. One constant source of requests for POP titles were the school music festivals and all-state competitions that take place across the nation. I couldn’t help but notice that with our own New York State School Music Association, the required list every year numbered majority Carl Fischer POP titles. The POP titles were a hot commodity!

Soon after the archival reprint service was launched, I noticed an interesting phenomenon recurring again and again, whereby a customer purchasing a particular piece of music would recount to me his or her personal experience with that composition that had prompted him or her to own the sheet music, whether purchasing it anew or else replacing a used copy. Was it because the means of purchase—contacting an archivist at a far-away research library—was so unusual and required some explanation or justification? Whatever the reason, it was my pleasure to receive email messages, telephone calls, and letters from customers expressing their appreciation for the service and for the access to the music, and also sharing their past personal experiences with the music they were purchasing. In addition, more than a few customers sent me programs from performances that access to the POP sheet music titles had made possible. As the curator entrusted with the responsibilities of maintaining and servicing the Archive, I was deeply touched and gratified by these many testimonial letters and email messages. One of my favorites came from an elderly bandsman, now deceased, who was a member and occasional horn soloist of a community band in Georgia, and who in his youth had been a member of the renowned Allentown (Pennsylvania) Band. After we had provided his band with the needed score and parts for Walter B. Rogers’ A Soldier’s Dream (a composition depicting a day in the life of a soldier), the gentleman wrote to me to express his appreciation for the availability of the music. Significantly, he wrote at some length of his love for that particular composition and how much it had meant to him to play that particular solo once more at his now-advanced age. “As someone in your position understands, probably better than most,” he wrote, “each soloist is in love with the piece he’s playing. He sees something that he wants to communicate to his audience.” He concluded his letter with these words: “’Soldier’s Dream’ was a favorite of Earl Heater. Earl was a great trumpet soloist with Sousa and our first chair trumpet in the Allentown Band. He died much too young. I suppose one day soon I’ll have to explain to him why I played his number the way I did. Probably, though, he’ll just give me that same nice smile he always did.”

Thus, it was clear that David Sengstack’s original vision of preserving the records of music archives at the Sibley Music Library for scholarship had now been complemented by an equally important initiative that was embodied in the archival reprint service, providing for the needs of applied musicians. Such was this latest manifestation of the longtime connection between Carl Fischer and the Sibley Music Library.

► Photos by David Peter Coppen, March, 2016:

Following processing of the collection (carried out in the summers of 2003-06), white Hollinger boxes line the rows of shelving. The presence of low-hanging pipes and conduits represented something to be watchful of on a daily basis, hence hard hats were initially issued to the team.

Conclusion of the loan

On two occasions, circumstances external to the Sibley Music Library impacted the Archive’s shelving configuration in the basement space. On each occasion, we were obliged to re-consider how to use the space efficiently while guaranteeing the safety of, and ease of access to, the Archive. The first was in the summer of 2004 when, as part of extensive renovations to the Eastman Theater, massive conduits were to be installed in the basement. By design, the planned conduits would run the entire length of the basement interior through its very center, i.e. directly through the heart of the shelving area. Installation would thus entail the removal of a significant linear footage of shelving, effectively dividing the space into two distinct areas on either side of the new installation. Faced with a decrease in shelf space, I opted to devote the basement’s shelf space entirely to three of the four record sub-groups—the last copies, the historical papers, and the new accessions, and to stage the production packages away from the shelving area in an unshelved but stable arrangement.

Later, in the spring of 2007, the SML received a compliance order from the UR Fire Marshal relative to a new regulation mandating that a designated number of inches of space be kept clear between any upper shelving and the ceiling in all storage areas. Under the new regulation we would lose a further extent of shelving, thus forcing a still more compact shelving arrangement of the Archive. Nevertheless, a uniform compacting throughout the basement ensured that the holdings of the three chosen sub-groups would remain kept safe and orderly. With the professional co-operation of our Office of Facilities and the contract workers, the Archive’s holdings were protected from any disorder during both the 2004 conduit installation and the 2007 re-configuring of shelving.

Finally, in the fall of 2012, we at Eastman were made mindful of environmental considerations in the basement after two heavy rainstorms occasioned some slight water penetration in the space. The underground location, with what we now believed was an actual potential for major climate catastrophe, would not prove permanently optimal for paper-based documents of major historical value. Those considerations were ultimately instrumental in determining to seek an orderly and amicable conclusion to the loan of the Archive. The Archive had been delivered to us on March 18th, 1999, and it was removed from Swan Street by two moving vans exactly seventeen years to the day later, on March 18th, 2016.

In looking back on this initiative, I am profoundly grateful to my superior, Dr. Dan Zager, former Head Librarian of the Sibley Music Library, who never flinched at my material requests in support of the Archive; my thanks also to Mr. Lauren Keiser, former President and CEO of Carl Fischer, to whose desk I always enjoyed immediate access by email or by telephone, and who received me cordially during my drop-ins to New York City; and a shout-out to my former colleagues at Carl Fischer, all of whom have moved on by now: Lola Kavonic (you were a delight to work with!), Kris Kazacs, Shira Flescher, John Guertin, and Subin Lim, with whom we at the SML interfaced on an almost daily basis on the archival reprint service; and to Sherri Zelina, who was Head Rental Librarian, who entertained my many questions about rental holdings with humor and patience.

Finally, I thank all of those Ruth T. Watanabe Special Collections team members who tirelessly pitched in over the years to support this initiative:

- in March, 1999, Seth Brodsky and Ian Quinn provided able support during our spring break outing to Manhattan;

- between 2001 and 2016, Katherine Axtell and Mathew Colbert provided essential in-office support for the archival reprint service;

- below-stairs, those who labored tirelessly to process the archive were Liz Hanan, Alex Dean, Ben Warsaw, Joshua Fein, Zachary Cairns, and Jeremiah Goyette;

- and the team members who provided research and photocopying assistance for the archival reprint service were Joshua Fein, Dieter Hennings-Yeoman, Zachary Cairns, Jeremiah Goyette, Aaron Grant, Hannah Swayze, Jacek Blaszkiewicz, and Austin Richey.

—Thanks to you all for helping to make it work. It was a pleasure to have worked with each of you!

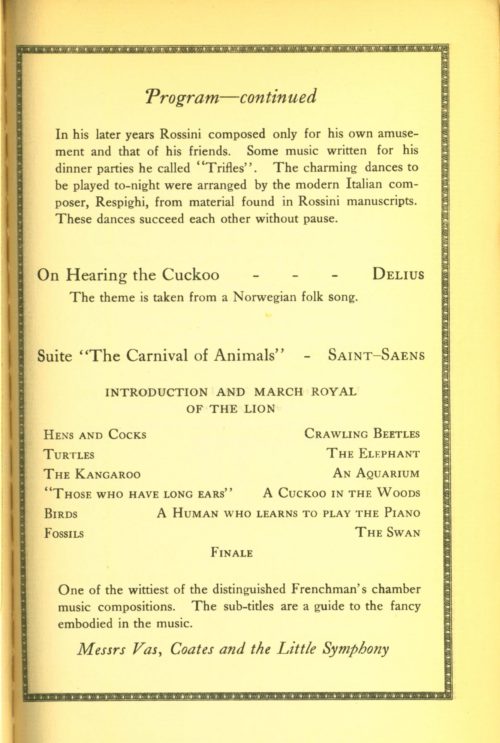

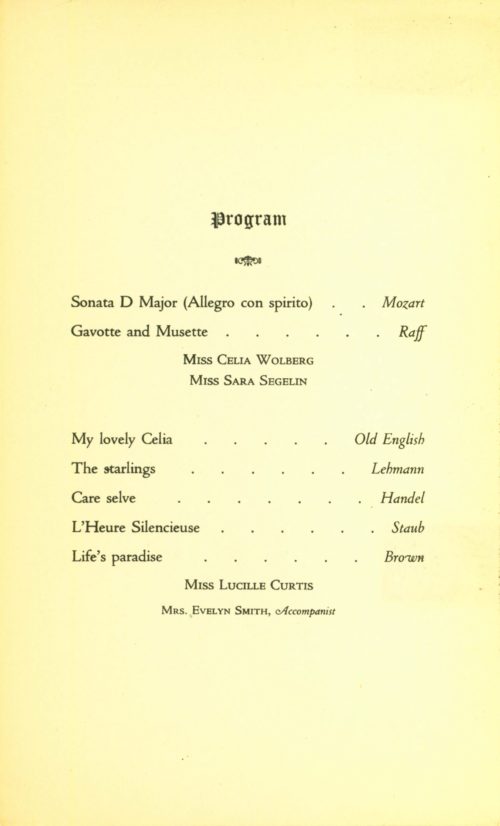

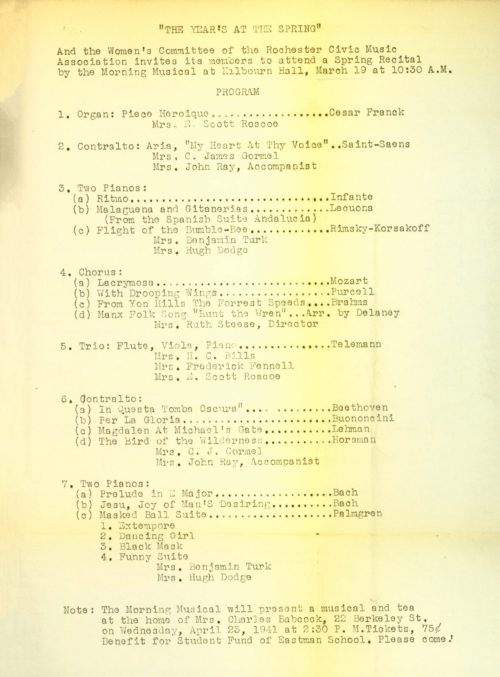

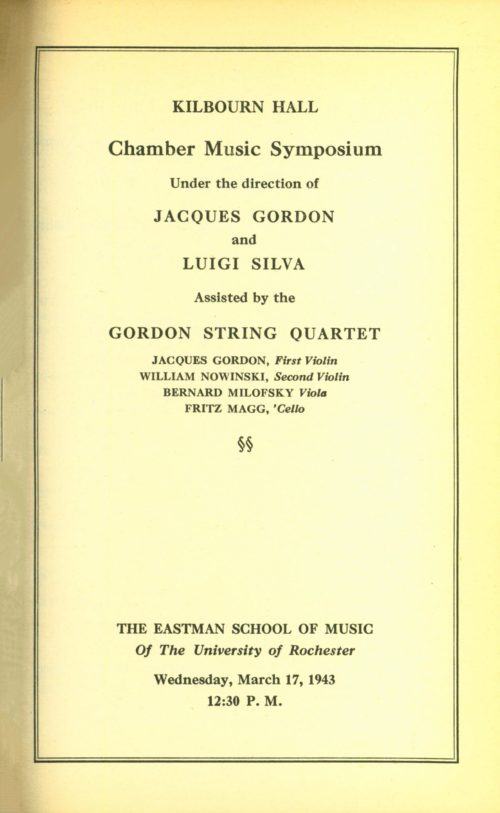

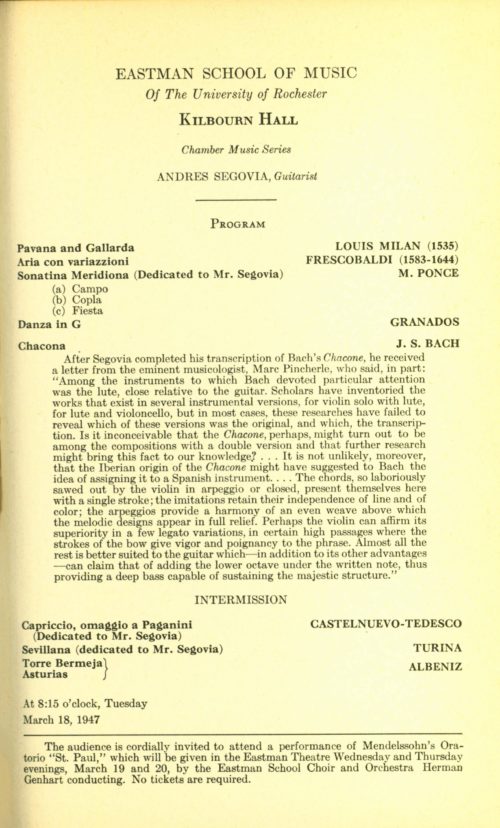

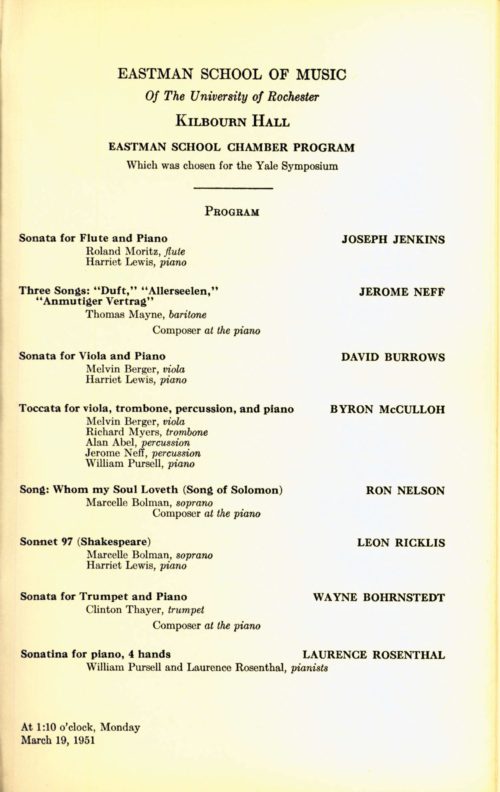

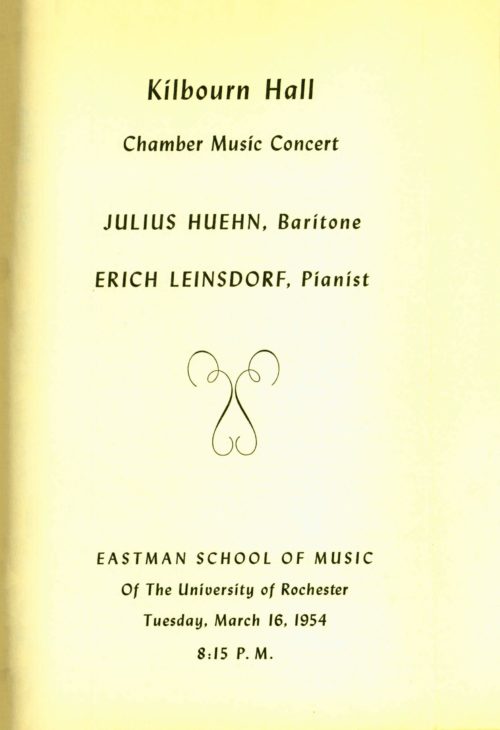

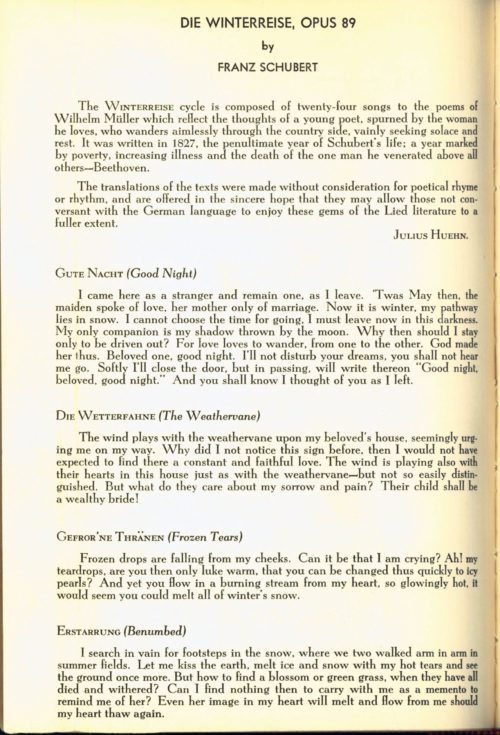

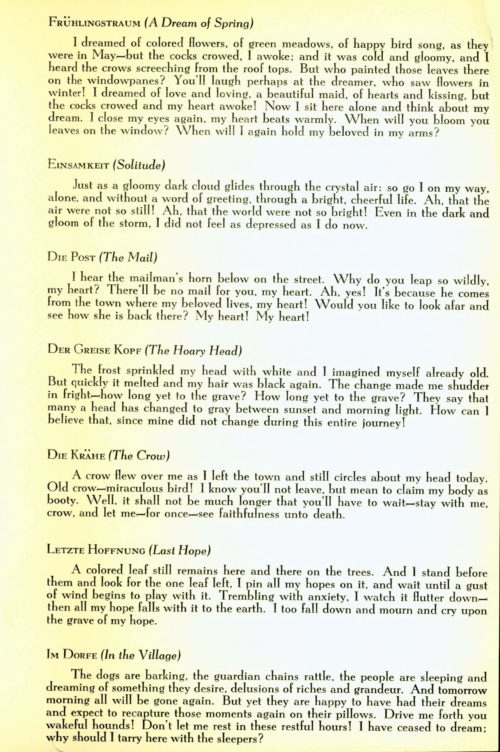

The Weekly Dozen

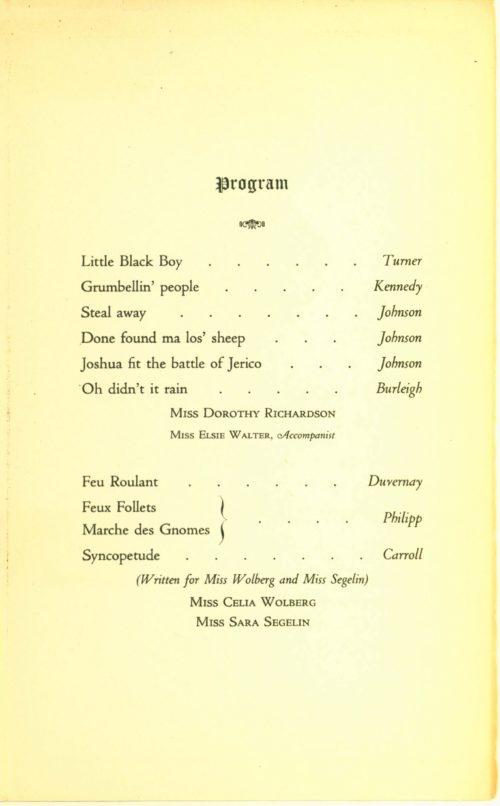

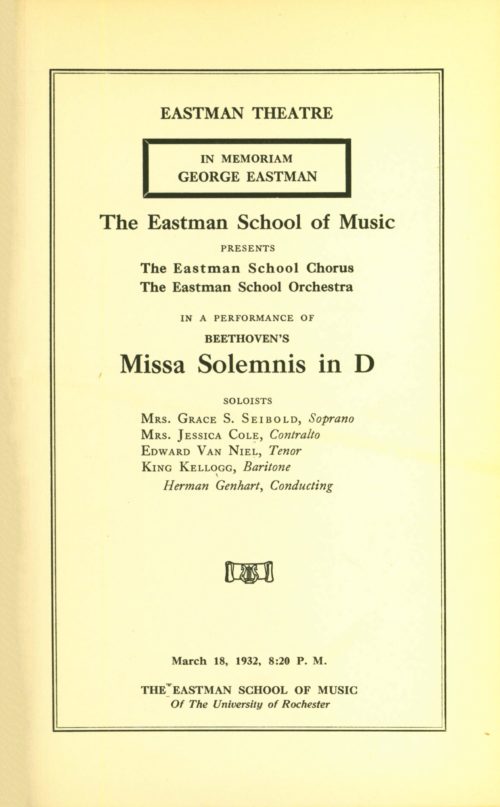

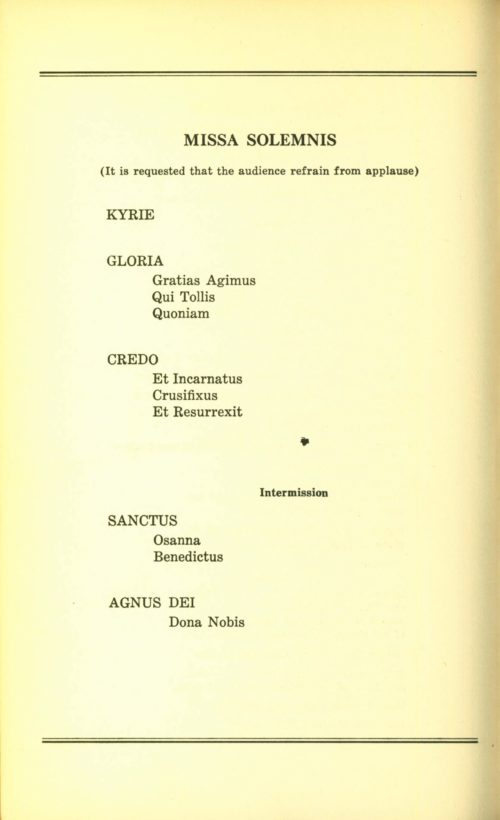

In this week’s Weekly Dozen, we recognize the special concert that was performed in memory of the late George Eastman in 1932; a performance by distinguished visiting artist Andres Segovia; a members’ recital of the local musical group The Tuesday Musicale which did much to organize musical activity in Rochester across one half-century; a recital by one of the Eastman School’s distinguished resident string quartets; a Kilbourn Hall recital by two truly distinguished artists, bass Julius Huehn and conductor Erich Leinsdorf, on this occasion finding service as a pianist; and some superlative student performances such as grace the Eastman concert calendar each week of the semester.

►March 16, 1926

►March 18, 1932