Published on Jan 31st, 2022

1933: Myra Hess’ appearance in the Chamber Music Series

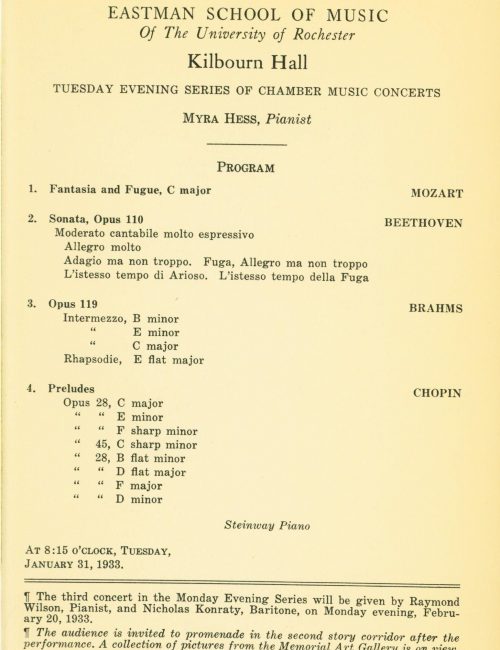

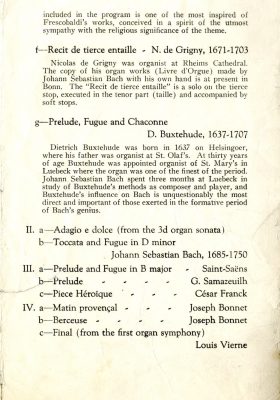

Eighty-nine years ago this week, on January 31st, 1933, English pianist Myra Hess appeared in recital in Kilbourn Hall. It was a return engagement for Miss Hess, who had previously appeared at Eastman in 1923 and 1926. The printed program is displayed here, together with a photograph that Myra Hess inscribed for Sibley Librarian Barbara Duncan as a presentation memento. Miss Hess’ appearance was under the auspices of the Eastman School’s Chamber Music Concerts, a recital series which brought tremendous prestige to the school.

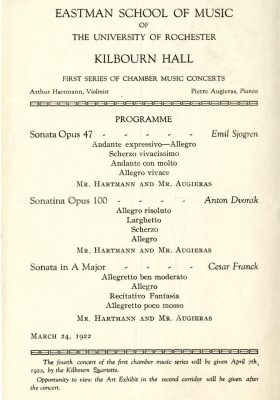

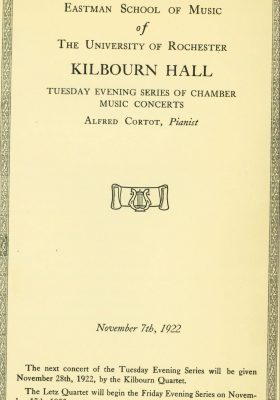

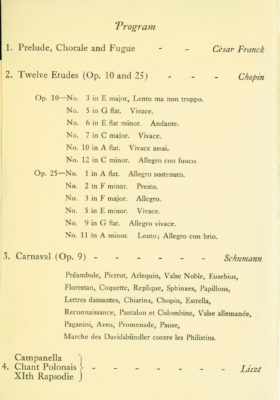

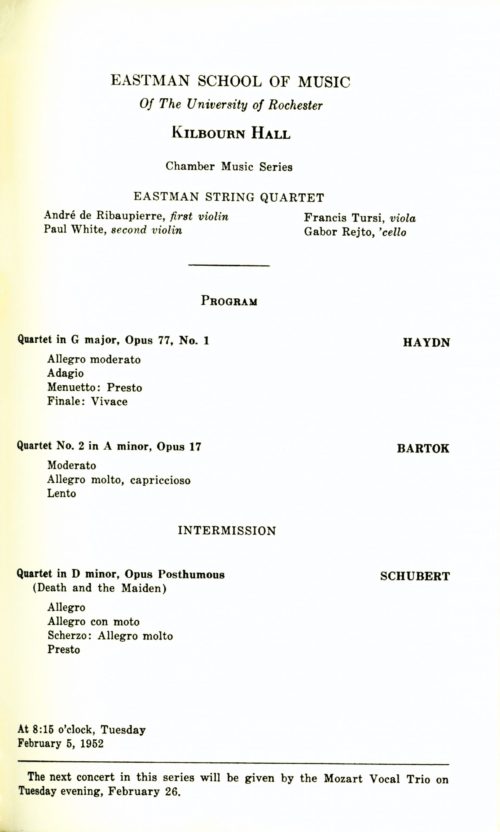

In the spring of 1922 the Eastman School’s Concert Bureau (as the Concert Office was initially called) launched an on-going series of Chamber Music Concerts, so named, with Kilbourn Hall as the venue; that new series would continue for several decades. In some seasons during the 1920s, ‘30s, and ‘40s there were actually two concurrent series of Chamber Music Concerts, e.g. a Monday evening series and a Tuesday evening series. While these concerts were a performing opportunity for Eastman faculty artists, they were most visibly and most significantly an opportunity for the school to present top-flight visiting artists of great renown. Under the auspices of the Chamber Music Concerts, Eastman audiences enjoyed the artistry of pianist Alfred Cortot, pianist Myra Hess, pianist Walter Gieseking, pianist Josef Lhevinne, harpsichordist Wanda Landowska, organist Joseph Bonnet, organist Louis Vierne, and various string quartets, including the London String Quartet, the Flonzaley Quartet, the Budapest String Quartet, and the Coolidge Quartet. Other artists who appeared in the Chamber Music Concerts included guitarist Andres Segovia, the Society of Ancient Instruments, the Aguilar Lute Quartet, the Trapp Family Singers, the American Ballad Singers (conducted by their founder, Elie Siegmeister), and lutenist Suzanne Bloch appearing in recital with harpsichordist Edith Weiss-Mann. Solo vocalists who appeared in the series included French baritone Pierre Bernac with his compatriot, composer-pianist Francis Poulenc, as his collaborative artist. Altogether, the Chamber Music Concerts brought a truly august procession of artists to Kilbourn Hall. Moreover, the cultural offering represented by the concerts was distinctly to the advantage of the wider Rochester community. As Eastman’s student newspaper The Note Book observed in 1922, at the start of the first chamber music season, the concerts afforded Rochester “a season of chamber music that Rochester has not known before.”1

With the passage of time and owing to the vastly increased need of Kilbourn Hall for student programming as the Eastman School’s enrollment grew, the chamber music concert series was modified with respect to both frequency of programming and frequency of guest artist appearances. In 1957-58 the series rubric was changed to Kilbourn Hall Chamber Music Series, and for two seasons (1957-58 and 1958-59) the printed programs were printed and distributed on specially tinted stationery with ornamental styling and borders, as seen on the February 4, 1958 program of the Eastman String Quartet displayed here. In 1959-60 the Concert Office returned to the standard printed program format for this series. The Kilbourn Hall Chamber Music Series under that name did not continue after 1966-67, and in time, the Concert Office founded new recital series such as we enjoy today.

► Printed programs of other recitals in this concert series:

March 24, 1922, Hartmann and Augieras

November 7, 1922, Alfred Cortot

February 26, 1923, Joseph Bonnet

December 15, 1936, Barrere and Britt and Salzedo

January 10, 1950, Bernac and Poulenc

Eastman String Quartet, February 4, 1958

By the time of her Eastman School appearances in the 1920s and ‘30s, Myra Hess (1890-1965) was enjoying enjoyed a thriving career on both sides of the Atlantic. Born in London, at a young age she won a scholarship to the Royal Conservatory where she was mentored by Tobias Matthay, who would prove to be a significant influence.2 She made her public debut in 1907 performing Beethoven’s Piano Concerto no. 4 with the New Symphony Orchestra under Thomas Beecham. She made her American debut in 1922 with a recital appearance in New York City’s Aeolian Hall. Over the next four decades she toured extensively, performing both the solo repertory and chamber music; she also taught a select number of students, including American pianist Stephen Bishop-Kovacevich (b. 1940). Several of her numerous commercial recordings continue in availability today in digital formats. What became undoubtedly the most memorable aspect of her personal and artistic legacy was her dedicated service to country and to music during World War II. Within the United Kingdom she earned the special affection of the British public for the daily lunchtime recitals that she organized at London’s National Gallery when theaters and concert halls were dark in the evenings (as, indeed, all of London was literally blacked out) owing to the Luftwaffe air raids. The concerts, to which the low admission price of one shilling was charged, began at 1 PM each weekday, Monday through Friday, and ran uninterrupted for more than six years. They were attended by a broad cross-section of society (including, on occasion, members of the Royal Family). As regards personnel, the concerts were a venue for seasoned performers and promising young performers alike. Altogether, between the first concert on October 10th, 1939 and the last on April 10th, 1946, Myra Hess organized a total of 1,698 concerts, which were attended by 824,152 people; she herself performed in nearly 150 of them. The concerts enabled the sum of 16,000 pounds to be contributed to The Musicians’ Benevolent Fund.3 The depth of Hess’ commitment is underscored by the fact that she took no fee for her part in organizing the concerts nor in performing in them. In recognition of her wartime service, King George VI promoted her to Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1941, after which she was styled Dame Myra Hess. Her performing career was ended after she suffered a stroke in 1961; she lived a solitary life until her death in 1965. She was warmly remembered by so many, including those in Rochester who had had the opportunity to hear her in person.

1 “The Season’s Music” in The Note Book, vol. 2, no. 1 (November 22, 1922), page 1. Printed copy shelved in the Sibley Music Library vault at Archives ML1 .E13n 1922-23; also accessible online . It is true that Rochester had had, since 1875, the opportunity to enjoy chamber music produced by the local group The Tuesday Musicale, but while The Tuesday Musicale’s programs were in every way respectable, they were not quite in the same league as the Eastman School’s new chamber music series. Activity of The Tuesday Musicale has previously been cited in “This Week at Eastman” and the Sibley Music Library holds a substantive collection of the group’s working papers; finding aid accessible here.

2 Later in life she would write the Foreword to a posthumously published digest of Matthay’s writings, The Visible and Invisible in Pianoforte Technique (Oxford University Press, c1960).

3 (These statistics are cited in the chapter “The National Gallery Concerts and After” by Howard Ferguson in the monograph Myra Hess by her friends (Vanguard Press, c1966). A rather more extensive account of the National Gallery concerts is found in the chapters “Playing Through the Blitz” and “Her Finest Hour” in Marian C. McKenna’s monograph Myra Hess: a portrait (Hamish Hamilton, 1976).

1962: the Eastman Philharmonia tour continuing

►Throughout the tour, receiving letters from home was a welcome thing for members of the Philharmonia. Most of their mail was delivered via diplomatic pouch. These two photos capture the delight experienced by the travellers when reading news from back home. Eastman School Photo Archive.

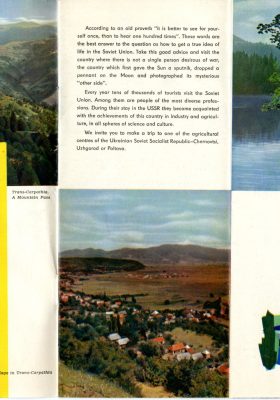

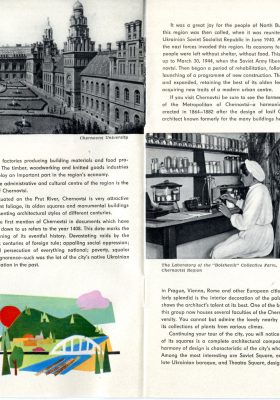

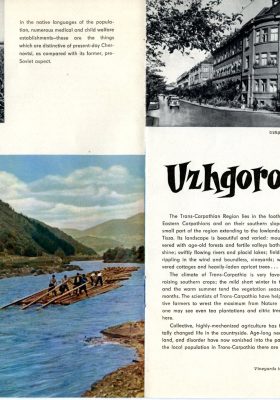

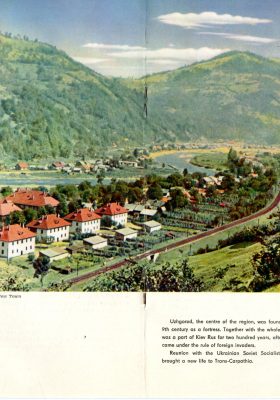

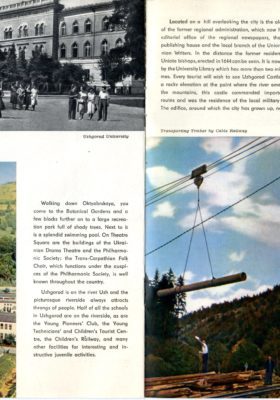

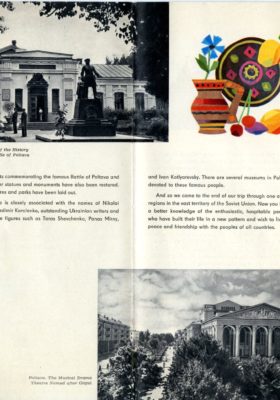

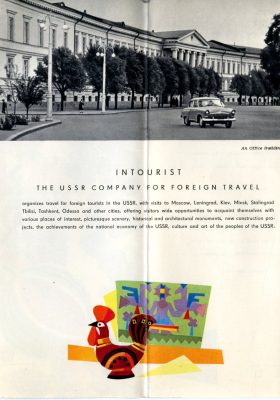

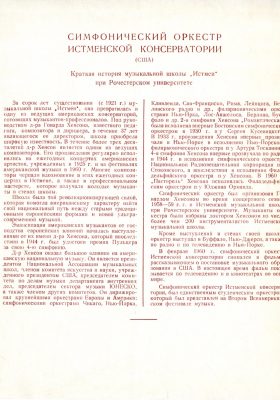

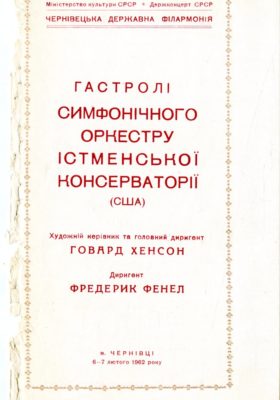

Sixty years ago this week, the members of the Eastman Philharmonia were continuing their landmark three-month tour with performances in the USSR. After performing concerts in Moscow in the last week of January, the orchestra members journeyed south to the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic for concerts in Odessa, Kishinev (today Chişinӑu), Chernovtsi (today Chernivtsi), Lvov (today Lviv), and Kiev (today Kyiv). Given that they were now travelling in the USSR’s principal agricultural region, their sightseeing itinerary included a visit to a collective farm outside of Chernovtsi. Bassoonist Richard Rodean described in his travel journal the choreographed manner of the visit, which included being greeted by the farm’s managers and local Community Party officials, and sitting for a question-and-answer session with one of the managers. The official insistence on making as favorable an impression as possible was also reflected in a tourist brochure found among Howard Hanson’s papers, displayed here. The color brochure, printed by Intourist (the USSR’s state-run tourist agency for visitors from abroad), is a vintage item of Cold War-era tourism, as it presents a sunny and attractive view of the region in which the Philharmonia members were now travelling, ignoring altogether the grim living conditions of many of the inhabitants.

Other opportunities were musical in nature. Mr. Rodean and other Philharmonia members attended a rehearsal of the Odessa Philharmonic, and were invited to sit with the orchestra and to play along with the rehearsal. The orchestra was rehearsing the Symphony no. 12 (“The Year 1917”) by Shostakovich, which had only just been composed in 1961. Mr. Rodean recounted that the orchestra’s bassoonists welcomed him warmly and were solicitous in assisting him through the unfamiliar Symphony. Following the rehearsal, the Philharmonia’s appointed interpreters had a hard time getting the Philharmonia members away from the Odessa musicians, so enthusiastic were they to welcome the Americans and to engage them in conversation. As Mr. Rodean wrote, “It’s amazing how a very few words can create a conversation for hours with musicians as long as the subject is music. The Symphony is really very exciting and fun to play. I imagine it will be available in the U.S. shortly for performance.” At the Philharmonia concert in Odessa that evening, the Odessa Philharmonic bassoonists showed up at the hall to greet their new friend Richard Rodean and to present him with a gift of several bassoon compositions by Soviet composers.

With the tour now in its third month, it is perhaps not surprising that the strains of travel, of food-borne illness and other ailments, and of living together at close quarters were finally taking a toll. Again, in Mr. Rodean’s words: “I think the length of the tour is beginning to show. The smallest incidents become grand episodes. Generally, everyone is becoming less tolerant of each other both musically and in living together.” One entry during the days in Kishinev recounts an anecdote that Philharmonia members had taken to placing bets with one another on the duration in any given performance of Hanson’s “Romantic” Symphony, which had a regular place on concert programs during the tour. “There seems to be renewed interest in the work since this started. Tonight I think I’m right in saying more people were watching their watch than were looking at Hanson.” Life in a touring ensemble.

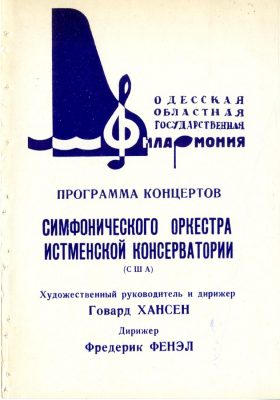

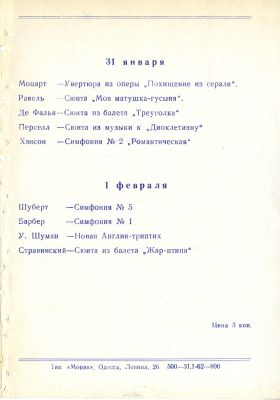

Displayed here are concert programs from Odessa (January 31st and February 1st), Kishinev (February 3rd and 4th), and Chernovtsi (February 6th and 7th). Next stop: Lvov.

Intourist travel brochure

Odessa (January 31 and February 1, 1962)

Kishinev (February 3 and 4, 1962)

Chernovtsi (February 6 and 7, 1962)

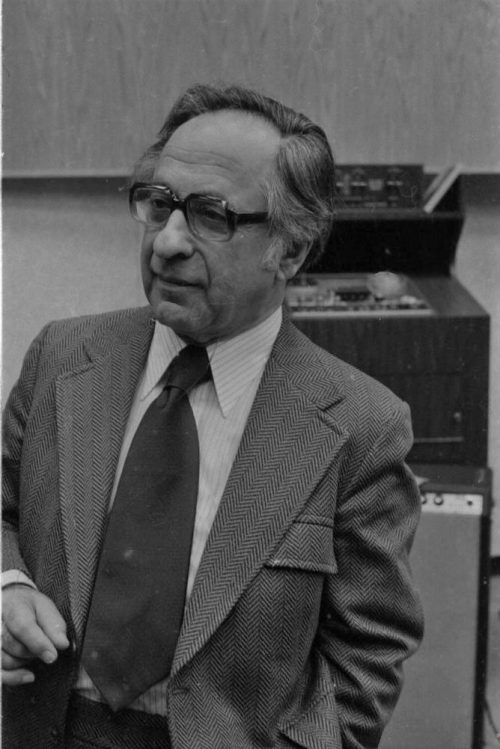

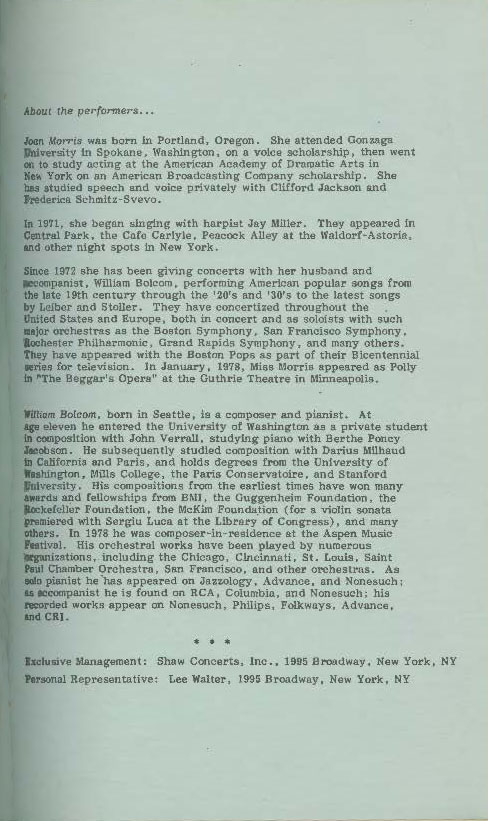

1979: Visit by critic and author Harold C. Schonberg

Forty-three years ago this week, Pulitzer Prize-winning music critic Harold C. Schonberg paid a visit to the Eastman School in the capacity of a guest speaker. Besides his many years’ coverage of music in The New York Times, Mr. Schonberg was the acclaimed author of such books as The Great Pianists.

The program had two scheduled events: a morning question-and-answer session on music criticism in Howard Hanson Hall, and an afternoon lecture on late 19th-century pianists in room 902 of the Annex. Mr. Schonberg was greeted by members of the Eastman community at a reception following his lecture.

This was only the latest courtesy call paid by a music critic to the Eastman School. During the first twenty-five years of the Eastman School’s annual Festivals of American Music, the renowned Olin Downes, chief music critic of The New York Times, had been a regular visitor as he covered the new music being performed at the Festivals. In 1971-72, during the Eastman School’s gala 50th anniversary year, four large-scale symposia were convened to examine vital questions in selected areas, the first of which was dedicated to music criticism.

► Q&A session in Howard Hanson Hall.

► Lecture in Annex 902.

► Photos by Louis Ouzer: R2661-3, R2661-5, R2664-20,R2664-17,R2661-18A, R2662-16A, R2662-17A, R2662-4A, R2662-5A, R2663-28A

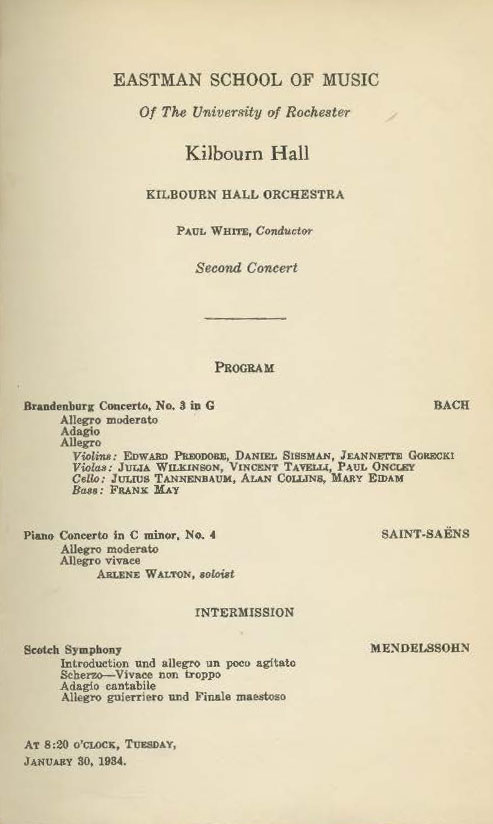

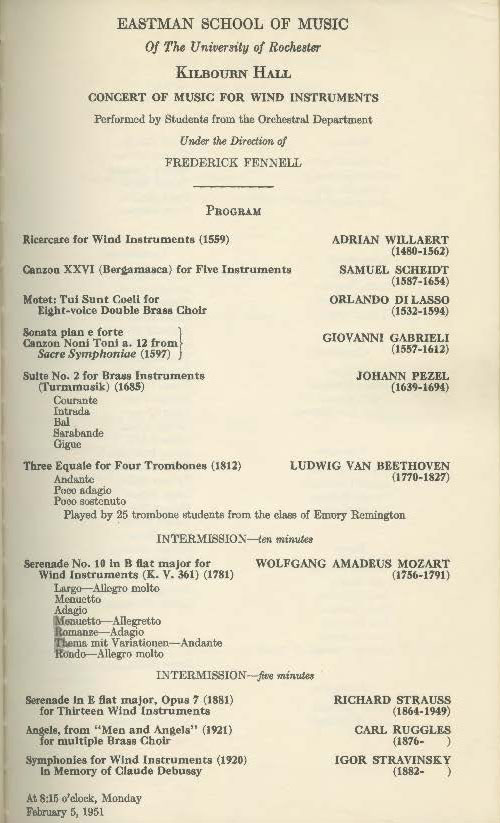

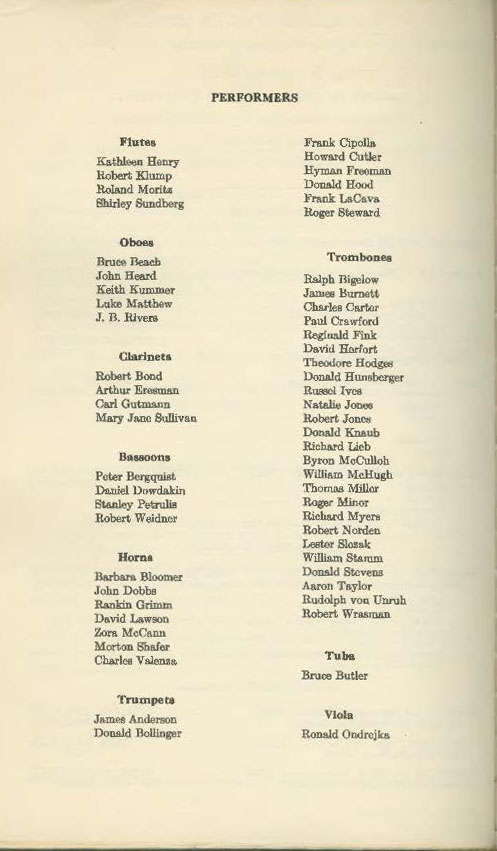

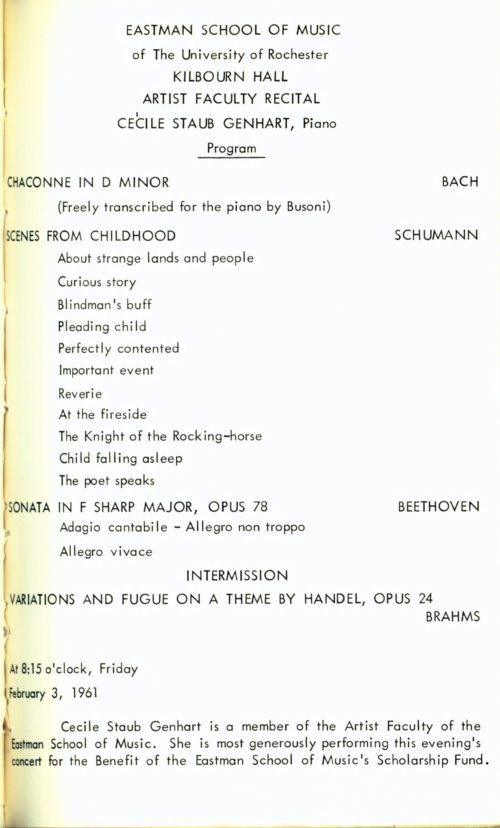

The Weekly Dozen

In this week’s “Weekly Dozen” we recognize one of the Eastman School’s earliest student orchestras, The Kilbourn Hall Orchestra (no relation to the later Kilbourn Orchestra); a concert of music for winds that Frederick Fennell would later regard as one of the formative milestones on the way to the founding of the Eastman Wind Ensemble; a host of faculty artists, including one of the Eastman School’s resident string quartets; some truly marvellous guest artists; and some superlative student performances such as grace the Eastman concert calendar each week of the semester.

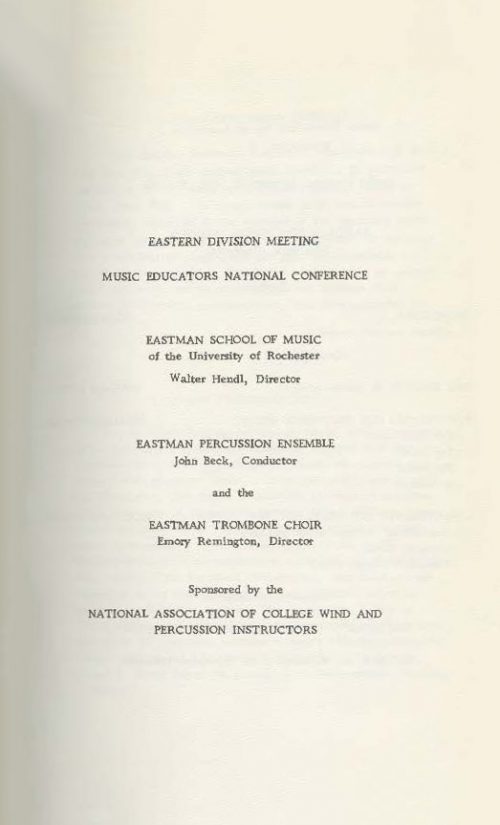

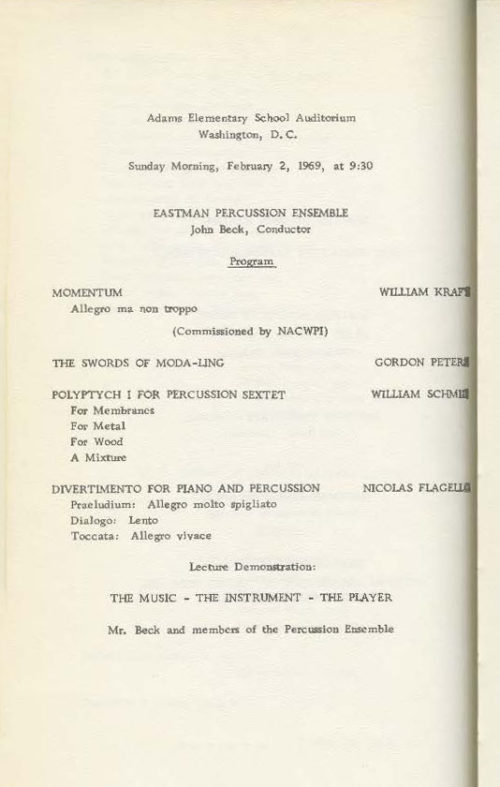

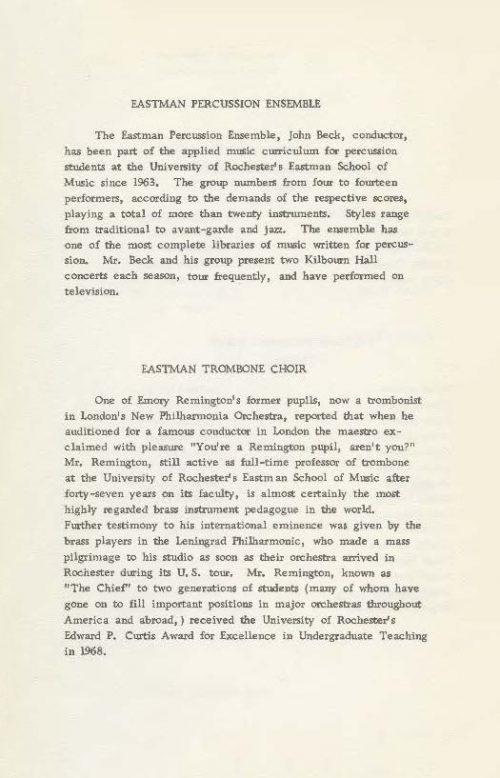

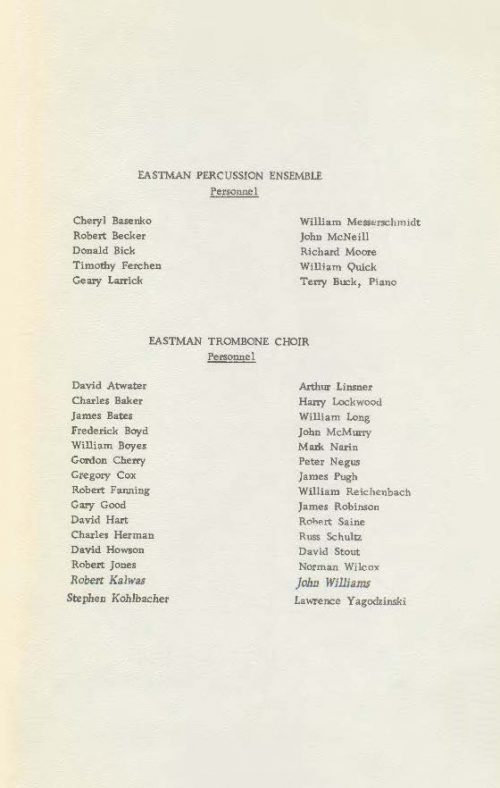

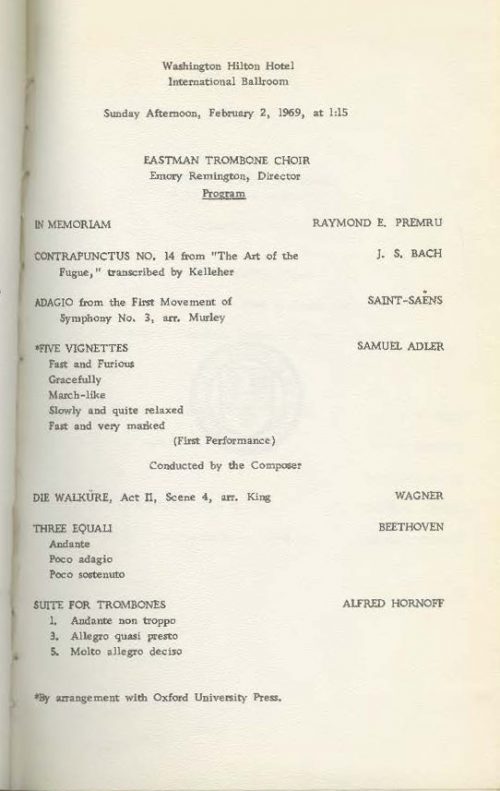

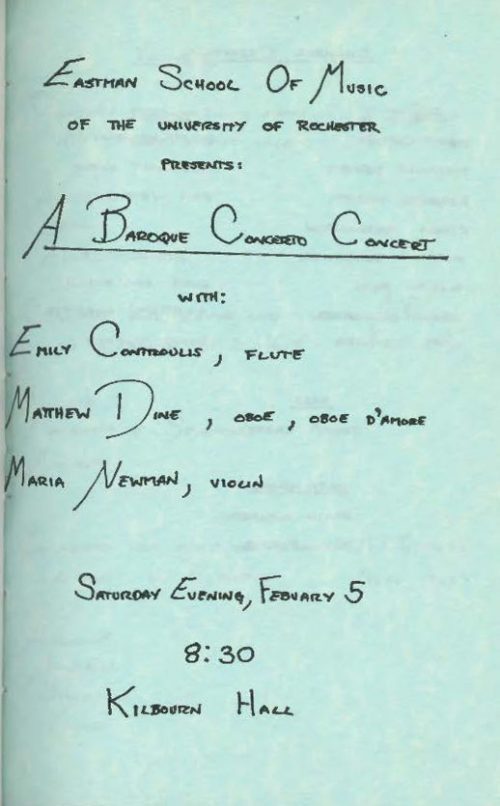

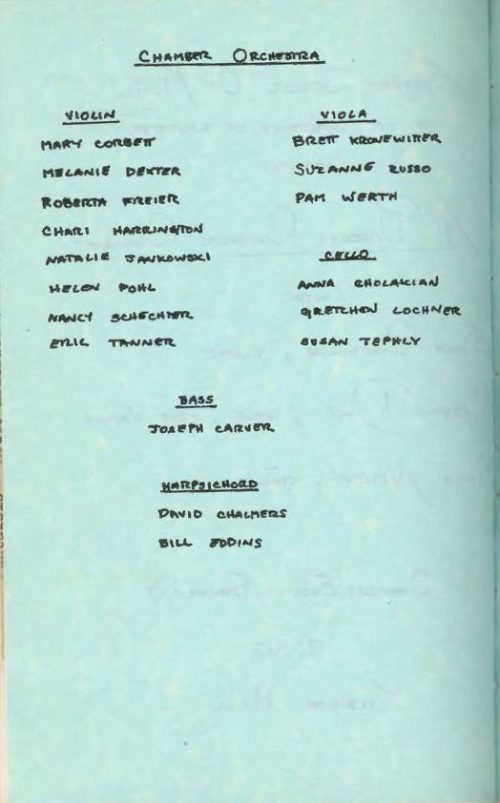

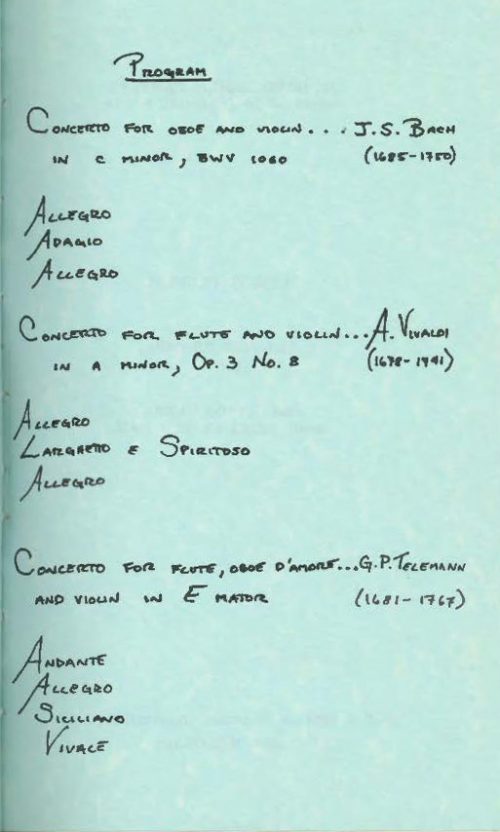

►February 2, 1969

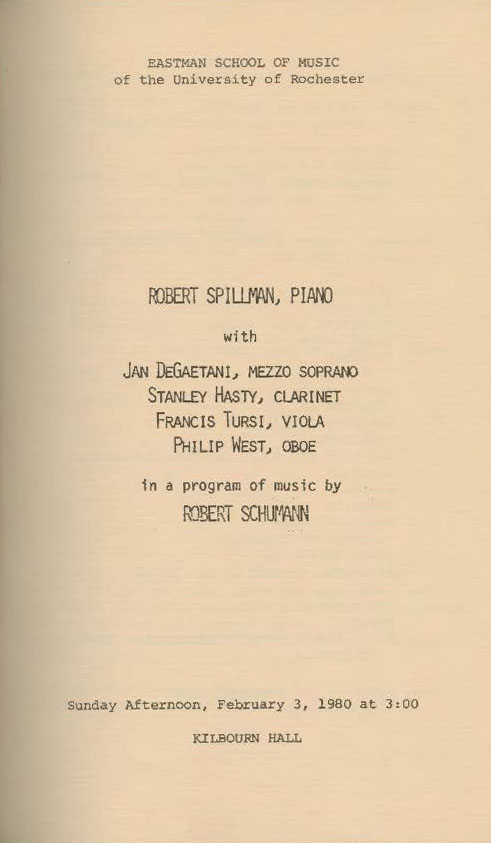

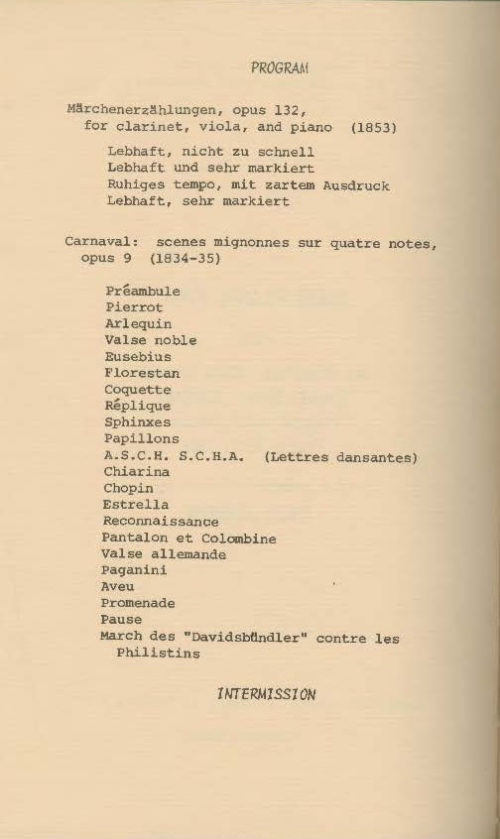

►February 3, 1980

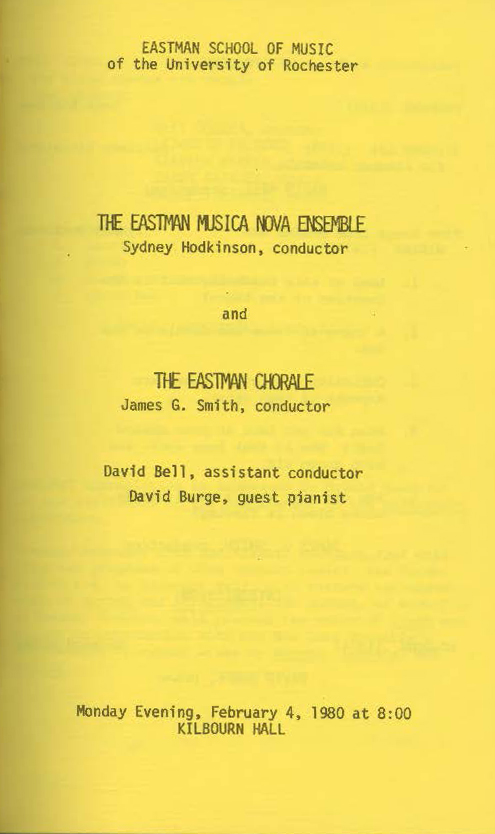

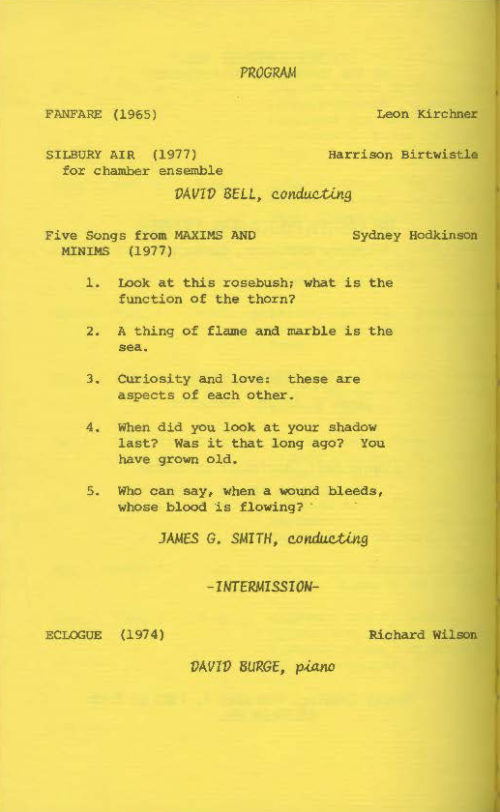

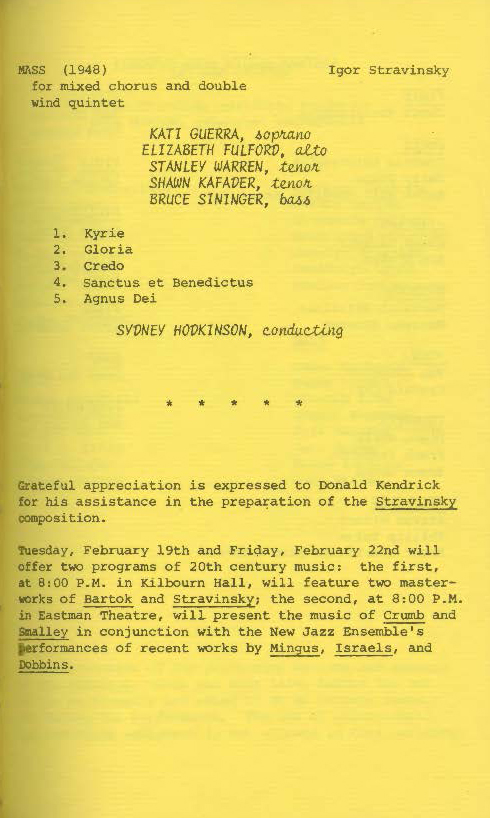

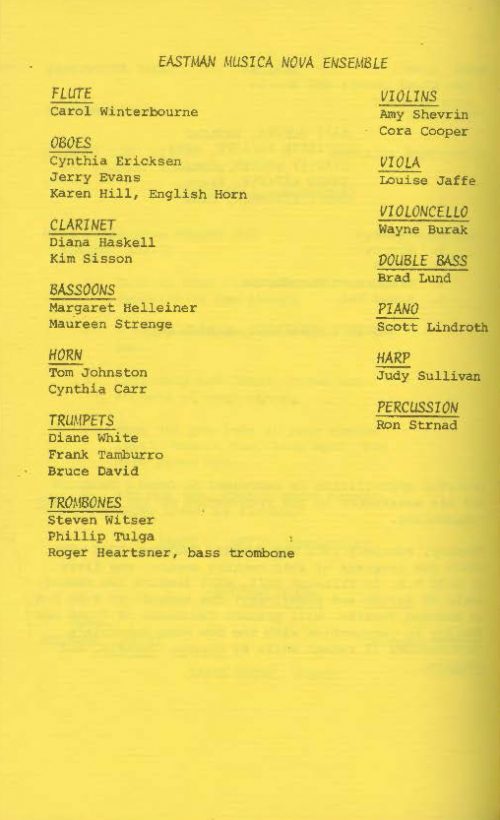

►February 4, 1980

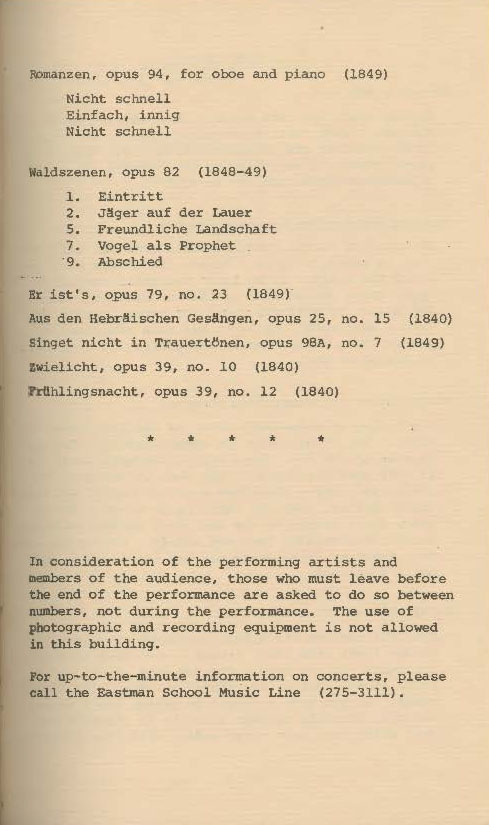

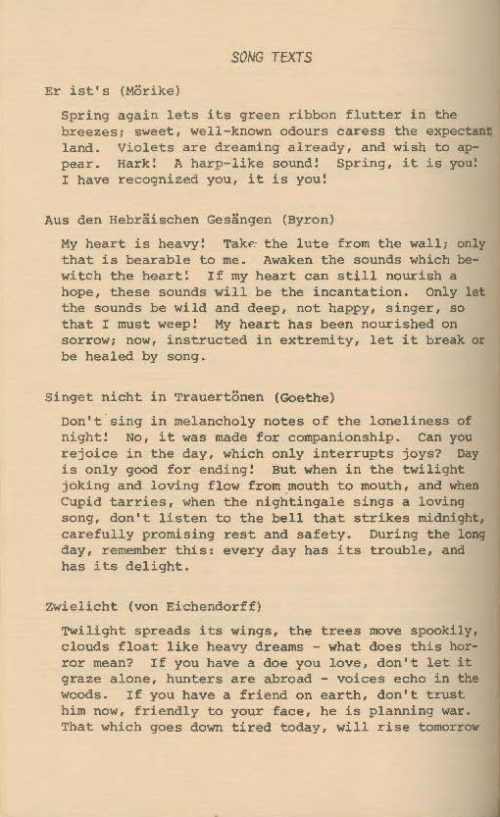

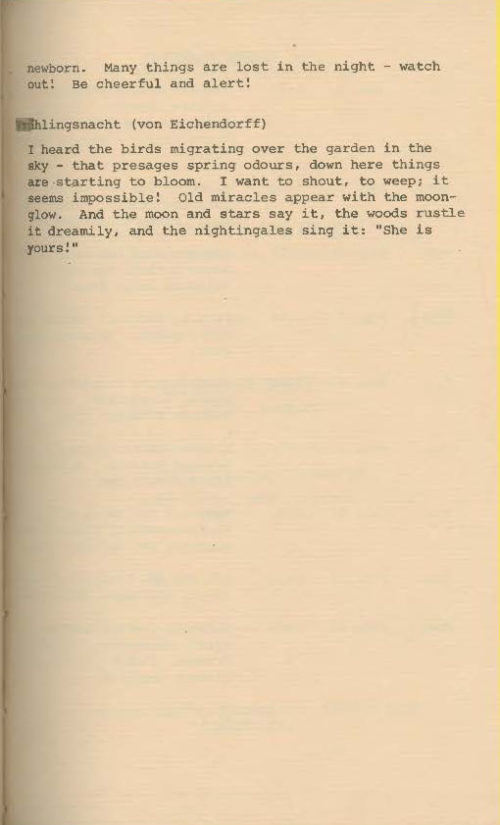

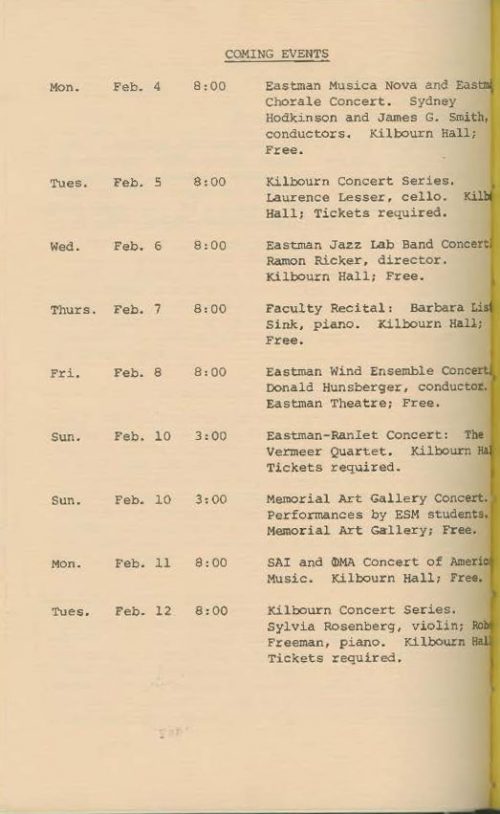

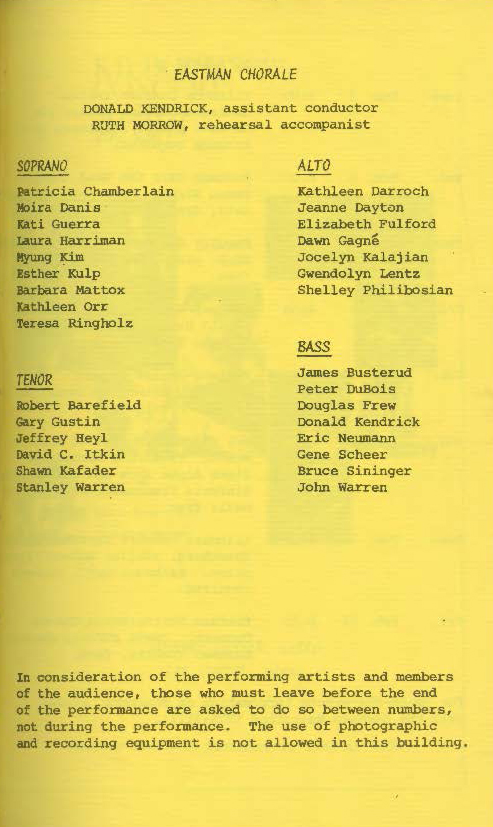

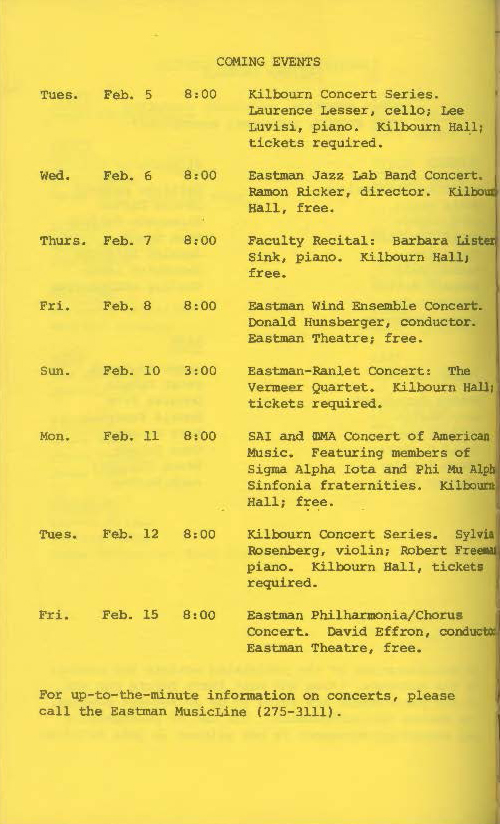

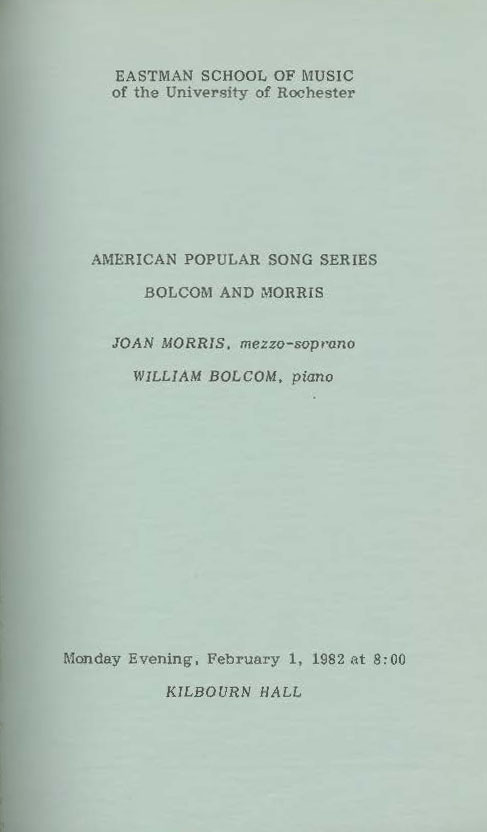

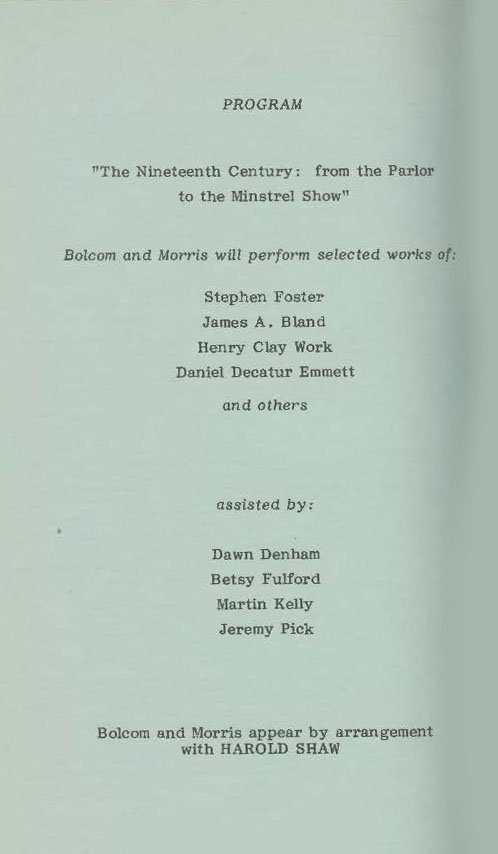

►February 1, 1982

►February 5, 1983

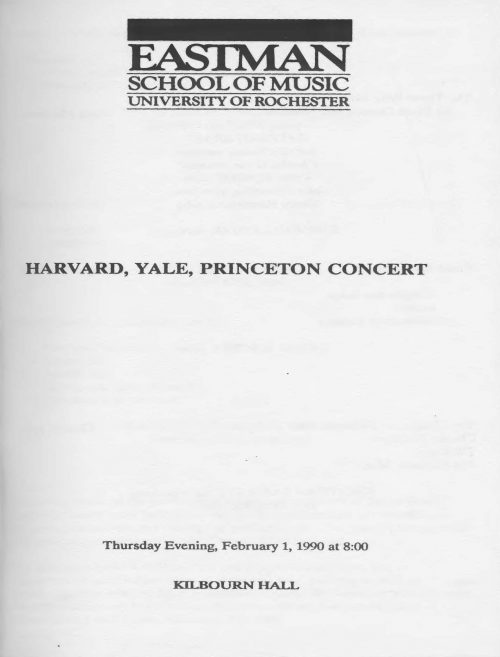

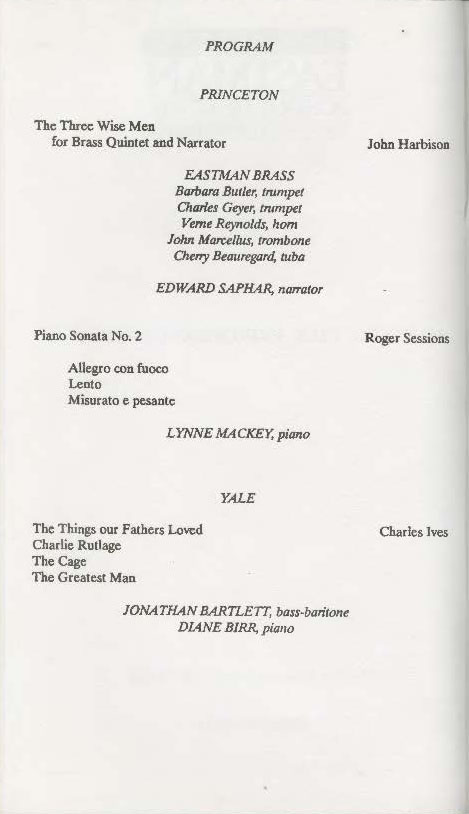

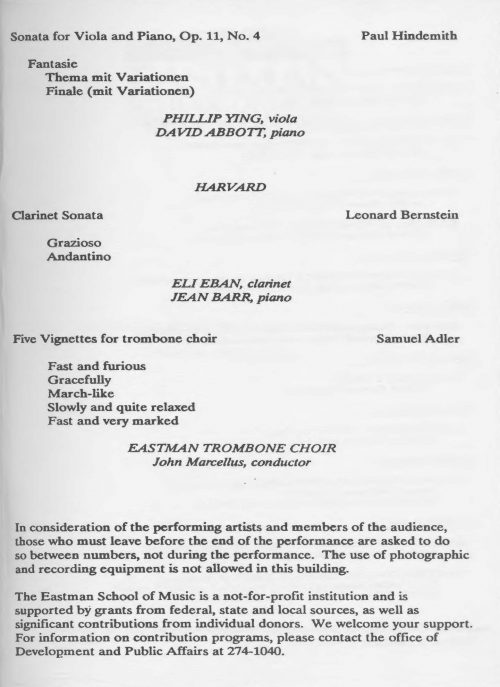

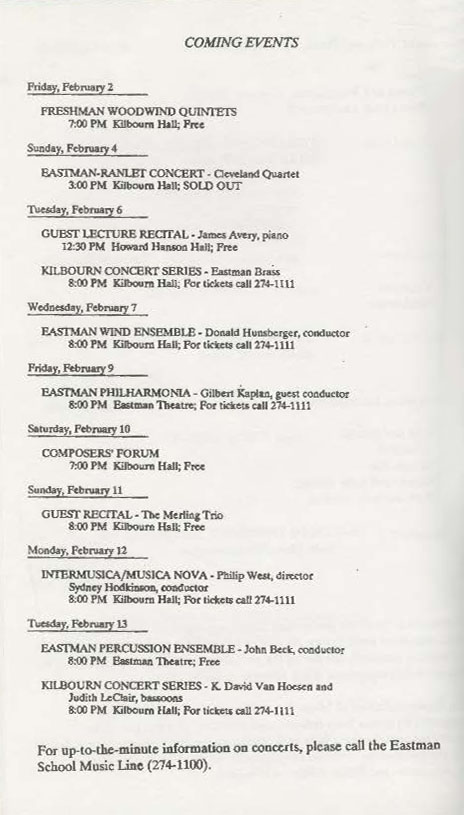

►February 1, 1990

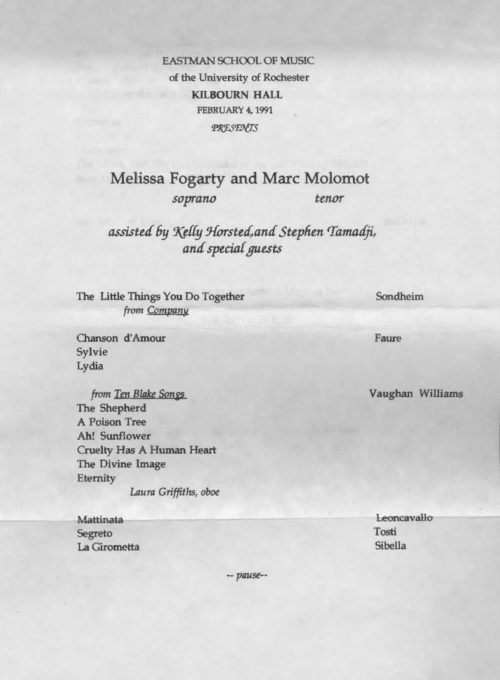

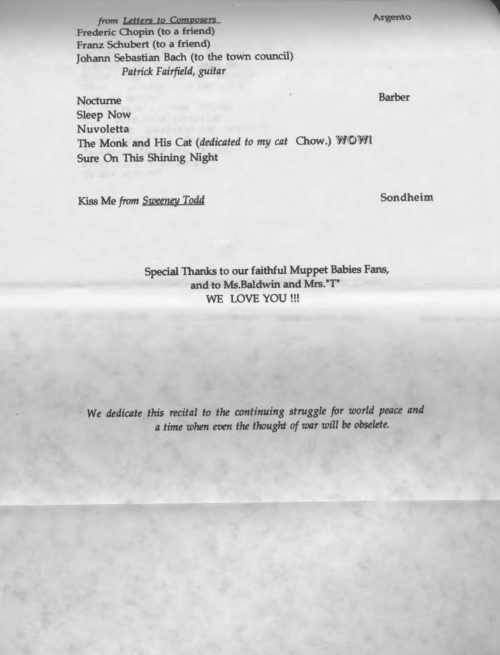

►February 4, 1991

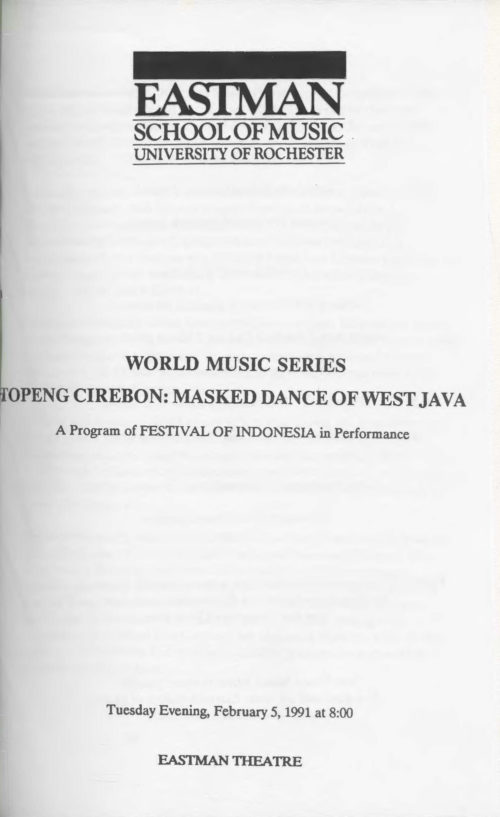

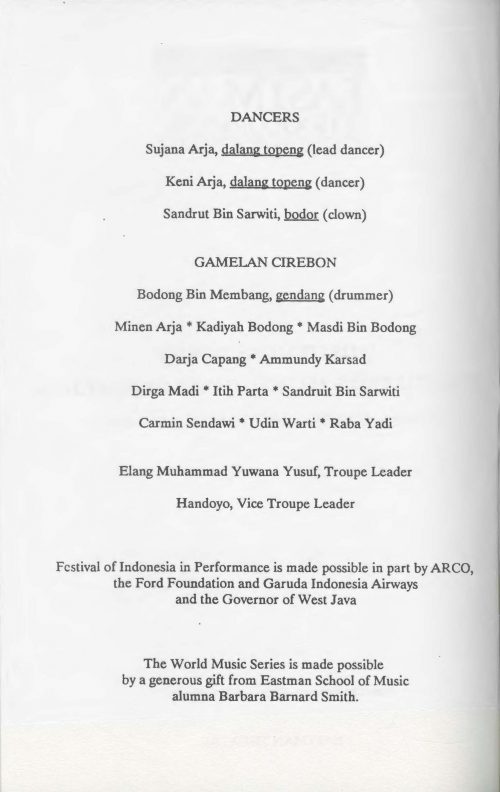

►February 5, 1991