Published on Jan 24th, 2022

1962: The Eastman Philharmonia on tour in the USSR

We continue to follow the members of the Eastman Philharmonia on their landmark tour in the late fall and winter of 1961-62. Sixty years ago this week, the 87 members of the Philharmonia were in Moscow, beginning their four-week sojourn in the USSR that would include concerts in Moscow, Odessa, Kiev, Leningrad, and elsewhere. Conductor Howard Hanson had regarded the Philharmonia’s time in Russia as the climax of the tour. He would later write in his Autobiography, “As we toured over Poland, our minds went forward with both anticipation and some trepidation to our coming four weeks in Russia. We realized that this was the crucial test. If we could succeed here, the entire tour would be a triumph. If we failed, then our tour would have been a failure, regardless of our success in the countries which we had previously visited.”

Hanson’s words are somber, indeed. If the mindset that he posited were, indeed, truly shared by all members of the Philharmonia, we can only imagine the sense of responsibility that they felt. They carried a message of peace and good will through music, much as other artists were doing during the Cold War. The geopolitical situation was fraught with tensions: 1961 was the year when President Kennedy had been embarrassed by the Bay of Pigs fiasco, and then had been thoroughly unnerved by General Secretary Krushchev at their Vienna Summit; the Western Allies had all been rattled by the construction, virtually overnight, of the Berlin Wall. There were grave tensions yet to come; the October Missile Crisis was still several months off in the future. Nor was the Space Race yet bringing any sense of unqualified accomplishment to the U.S., for ever since the USSR had launched Sputnik in 1957, the Americans had suffered one setback after another; John Glenn’s successful orbital mission was still several months away in 1962. Indeed, as Americans surveyed the international situation in 1961, there was much to be nervous about, but at the same time, artists and musicians were carrying out their own mission on their own terms, facilitated by such initiatives as the President’s Special International Program for Cultural Presentations, which was the very program that had sent the Eastman Philharmonia abroad.

On January 24th the Philharmonia members flew from Warsaw to Moscow, where they would spend four full days. The time in Moscow was packed with activity. On their first full day in Moscow, U. S. Ambassador Llewellyn E. Thompson hosted the Philharmonia members at a cocktails reception at Spaso House, the official residence of the U. S. Ambassador in Moscow. The reception’s guest list, numbering five pages altogether, included many of the most well-known figures of the Soviet musical establishment, together with a number of American correspondents, staff members of the American embassy, and cultural officers from several other embassies. (Several of the invited correspondents are well remembered today for their exemplary reporting and coverage during the Cold War years. In addition, one of the U. S. Embassy staff members on the list, Mr. Jack Matlock, was later appointed U. S. Ambassador to the USSR (served 1987-91).) The reception was reminiscent of other diplomatic engagements enjoyed by the Philharmonia during the tour, but this one was unquestionably the most high-profile. Following the U. S. Ambassador’s reception, the orchestra members attended a performance of Prokofiev’s opera War and Peace at the Bolshoi Theater.

As recounted by bassoonist Richard Rodean, BM ’62, MM ’64 in his travel journal, five members of the Philharmonia’s woodwinds section had been performing together as a quintet on several occasions throughout the tour. Mr. Rodean recorded in his journal that the five performed the Quintet by August Klughardt (1847-1902) — likely the composer’s opus 79 among his many chamber works — at the Ambassador’s reception, performing on a raised stage “hardly large enough for all of us” before an audience that included “our worst critics—the members of the orchestra.” Which prompts the question: isn’t it always the most difficult thing to perform before one’s own peers?

Over the following days, their sightseeing itinerary took in numerous sites, including Moscow University, the Olympic stadium, the Kremlin and its environs (including its cathedrals and Red Square), and the Exhibition of Achievements and National Economy (abbreviated in Russian as ВДНХ (VDNKh)), a sprawling complex of pavilions housing elaborate displays of scientific and economic achievements. (Personal recommendation: when in Moscow, do not pass up VDNKh, an essential destination in Moscow! For ease of transportation, it has its own Metro stop on the No. 6 line.) In Moscow as elsewhere, Philharmonia members took advantage of shopping opportunities, in particular seeking out music stores for printed music and recordings.

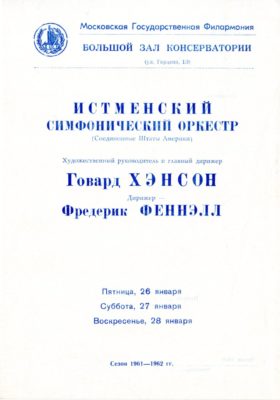

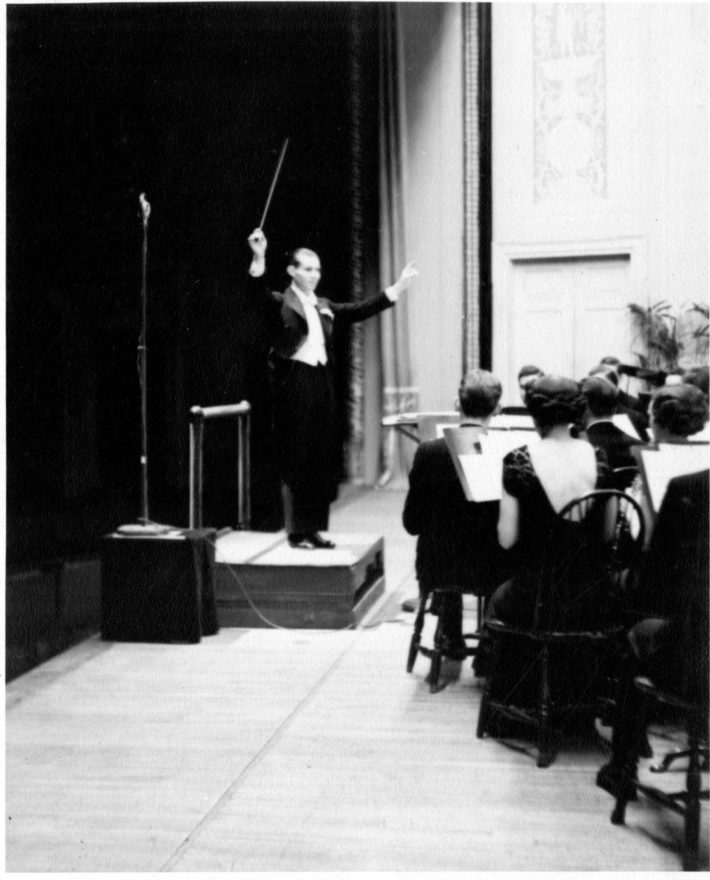

Inevitably, the major business of the time in Moscow was performance. On January 26th, 27th, and 28th the Eastman Philharmonia gave concerts in the Great Hall of Moscow Conservatory. (When translated from the Russian, the Conservatory’s full name is Moscow State Conservatory in the name of P. I. Tchaikovsky.) Composer Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky had been appointed to the Conservatory’s faculty immediately upon its founding in 1866; the Conservatory has borne his name since 1940. Today Moscow Conservatory is the second oldest conservatory in Russia, after St. Petersburg Conservatory. It is more than likely that the iconic space of the Conservatory’s Great Hall was beginning to be recognized by the international musical audience after television coverage of such high-publicity events as the 1958 International Tchaikovsky Competition. (Today the Soviet Television channel on YouTube promotes a 1958 film of Van Cliburn performing with the Moscow State Philharmonic under conductor Kirill Kondrashin in the Great Hall after scoring his victory in that competition.)

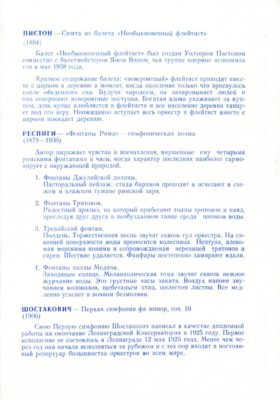

Besides works by recognized European composers, the three Philharmonia concert programs also featured works by American composers Samuel Barber, William Schuman, and Walter Piston, as well as Hanson’s own Symphony no. 2 (“Romantic”) and his Elegy in Memory of Serge Koussevitzky. In addition, the Philharmonia performed one work by a living Russian composer, the Symphony no. 1 by Dmitri Shostakovich. Each of the three concerts was concluded with the predictable string of encores such as had been obligatory at each of the Philharmonia’s concerts on tour. By the recollections of more than one man who recounted the events later, John Philip Sousa’s Stars and Stripes Forever brought down the house each time it was played.

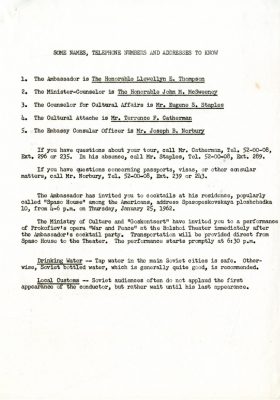

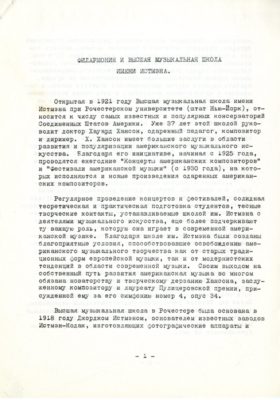

► From the Howard Hanson Collection. Information sheet provided to Philharmonia members providing details relevant to their stay in the USSR, including their complete USSR itinerary (annotated by Hanson), and one full page addressing what could and could not be photographed. Howard Hanson Collection.

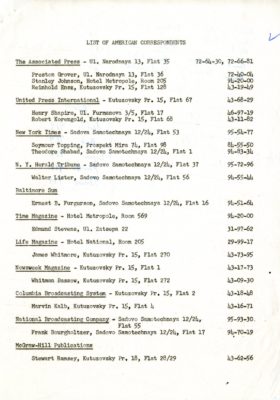

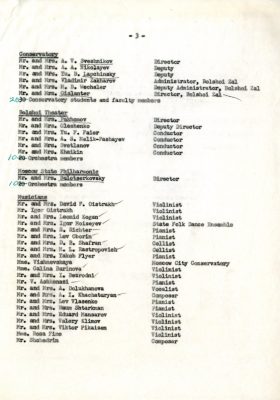

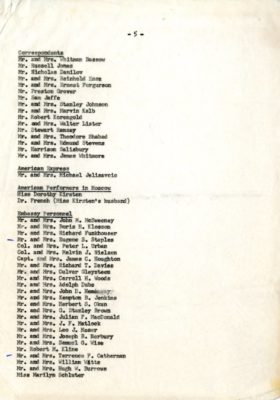

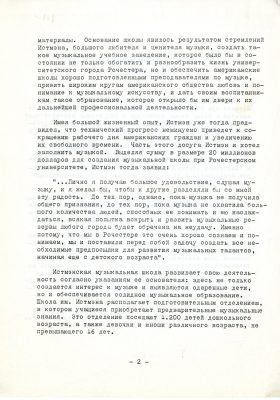

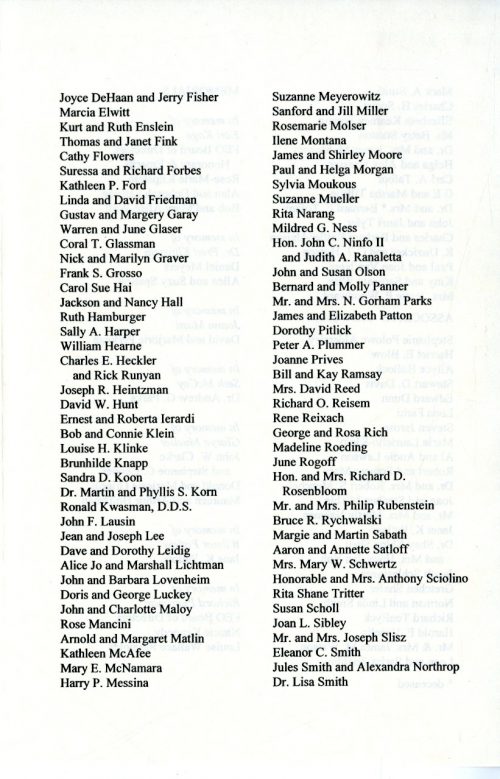

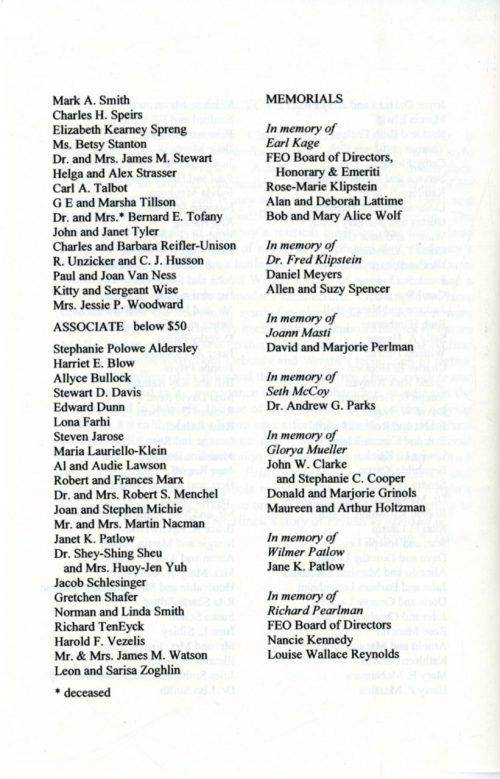

► Guest list (5 pages long!) for a cocktail reception honoring the Eastman Philharmonia hosted by the U. S. Ambassador to the USSR at Spaso House (the U. S. Ambassador’s official residence in Moscow). Note that the list includes some very distinguished names from the Soviet musical establishment, including conductor Kirill Kondrashin, performers Galina Vishnevskaya and Mstislav Rostropovich, and composers Dmitri Kabalevsky and Dmitri Shostakovich and their wives. Among the U. S. Embassy personnel cited on the list is Mr. J. (Jack) Matlock, a future U. S. Ambassador (served 1987-91). Howard Hanson Collection.

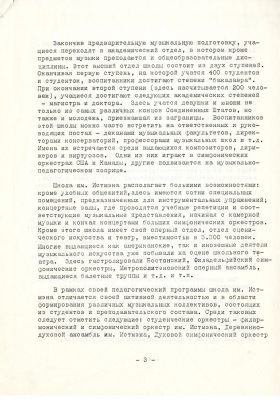

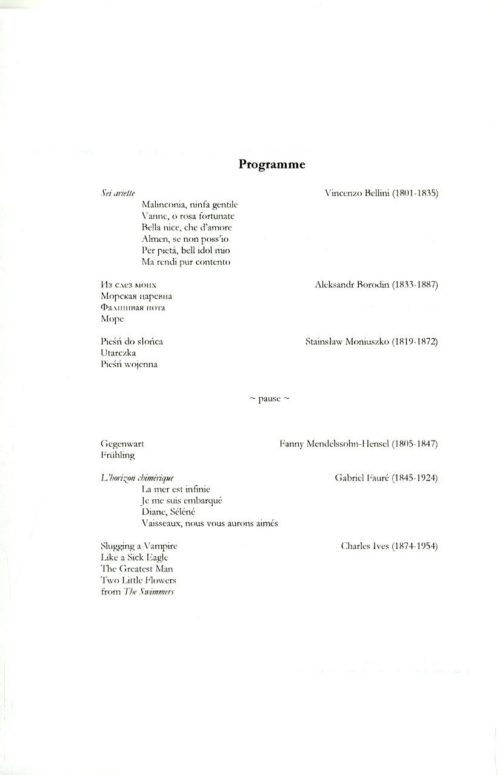

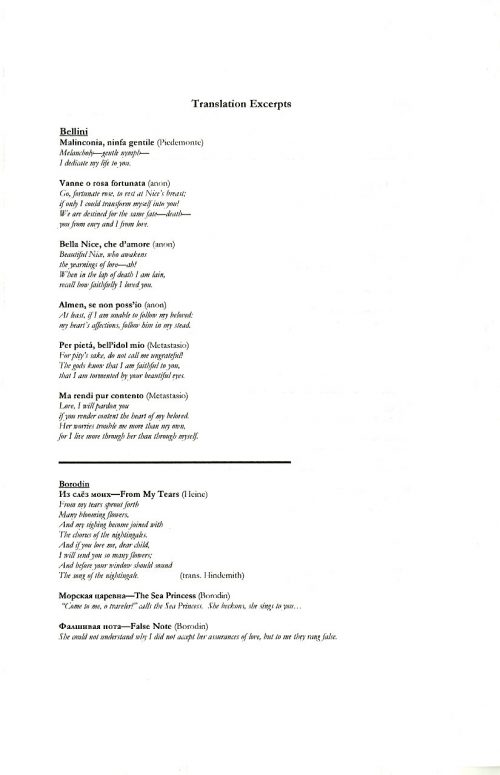

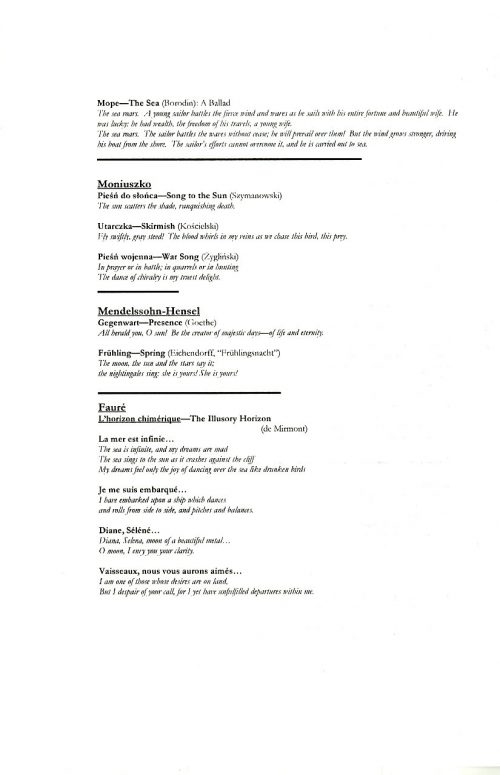

► Printed program for the Eastman Philharmonia concerts in the Great Hall of Moscow Conservatory on January 26th, 27th, and 28th. Works by American composers Hanson, Samuel Barber, William Schuman, and Walter Piston were to be programmed, as well as one work by a living Russian composer, the Symphony no. 1 by Dmitri Shostakovich. Eastman School Concert Program file.

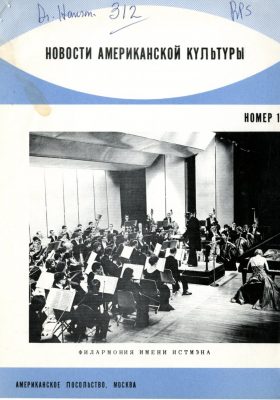

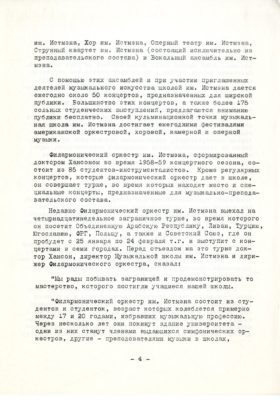

► One issue of an on-going publication “News of American Culture” of the U. S. Embassy in Moscow, printed for the Russian-speaking audience. This issue profiled the Eastman Philharmonia and its background. Howard Hanson Collection.

According to Mr. Rodean’s travel journal, the first concert in the Great Hall had been filmed by NBC-TV for promotion via the “Today” show back in the U.S. Already immediately the concert, Philharmonia members learned that owing to the success of the event, they could expect concert engagements in both New York City and Philadelphia after returning home. The concert on January 28th was broadcast over Soviet television. That concert included two Russian works: the Shostakovich Symphony no. 1, and also Anatole Liadov’s The Enchanted Lake as an encore. Mr. Rodean’s description of the audience reception at and following the first concert, together with his own personal response to same, is worth quoting at length:

“What an evening! I must admit most of us were quite apprehensive about this concert. The theater is large and spacious. Upon arriving in the hall we noticed movie cameras, recording equipment, floodlights and many spotlights strewn about. This was to be a big affair. NBC-TV filmed much of the concert for the Today show in the U.S. The lights were on throughout the concert focused on both the orchestra and the audience, which filled the house to capacity. Although they were slow to get started by the end of the concert it was safe to say we were a smash! We exhausted all of our encores but they refused to leave. Finally when they kept chanting M A R C H in English, we repeated the Stars and Stripes, much to their pleasure. In true Russian tradition we applauded the audience, making quite a noisy scene. When most of the audience finally left, the enthusiasm of the orchestra could be contained no more. Quite spontaneously, we played without conductor. “Bugler’s Holiday” (by Leroy Anderson) ! The press men who were packing their equipment quickly set up again and filmed and photographed this display. It was a most exciting climax to this rave reception in a city we knew nothing about. A crowd of Russians waved goodbye to us as we drove away from the hall to our hotel. After supper, including borscht, while riding the elevator, a woman took out a program from the concert and indicated she wanted to have me autograph it. This set the entire elevator load of people into an excited exclamation of bravos for the concert. Several Soviet pins were stuck on me . . . I have never seen such a display of friendship and sincere appreciation. If anyone ever questions the value of this trip to international relations they should have been here tonight. Edward (one of the orchestra’s facilitators on the tour) announced at supper tonight that due to our success tonight in Moscow, concerts in New York and Philadelphia are a certainty.”

By general consensus, the time in Moscow had been a triumph. On January 29th, the Philharmonia members left Moscow by train at 11:15 AM, bound for Odessa; they arrived in Odessa at 3:20 PM on January 30th, a trip of 28 hours. In Odessa the Philharmonia members stayed at the Hotel Odessa overlooking the harbor and the Black Sea. Mr. Rodean initially wrote in his travel journal that he had found the journey by train an advantage on account of the rest that it afforded him. However, other Philharmonia members were having different thoughts, for when they found out that Hanson had travelled to Odessa by plane, they took a vote to express their displeasure. Nevertheless, I will offer the observation that the opportunity to see the varied landscape by train was not one that many Americans had had the opportunity to enjoy up to that time. Having myself logged a good many kilometers by rail in Russia, I’ll recommend that if you ever get the chance to travel across Russia or any other of the former Soviet republics by train, DO SO. It’s an experience not to be missed.

In Odessa the Philharmonia members stayed at the Hotel Odessa overlooking the harbor and the Black Sea. They would perform concerts in the city’s Philharmonic Hall on January 31st and February 1st. Next stop: Kishinev.

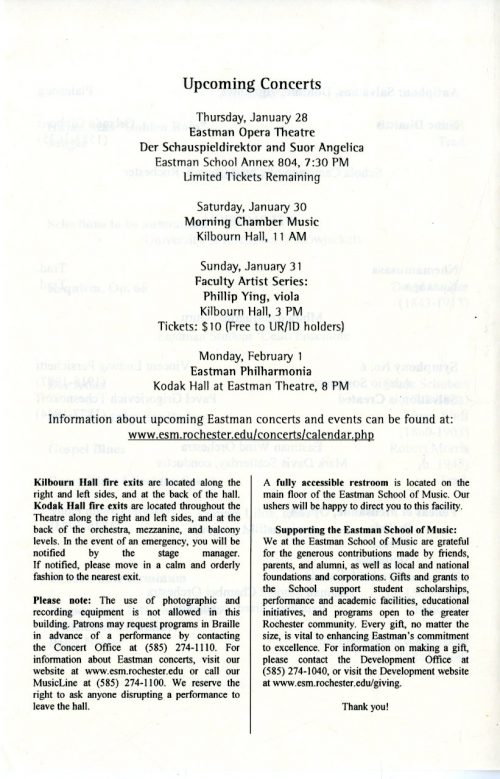

The Weekly Dozen

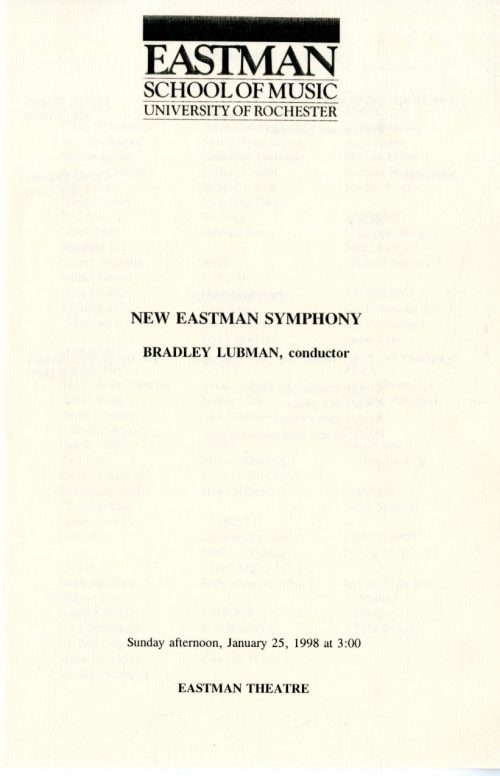

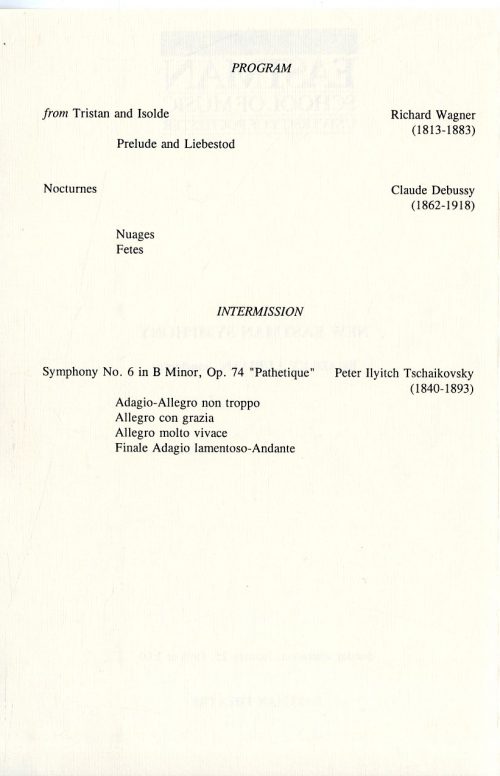

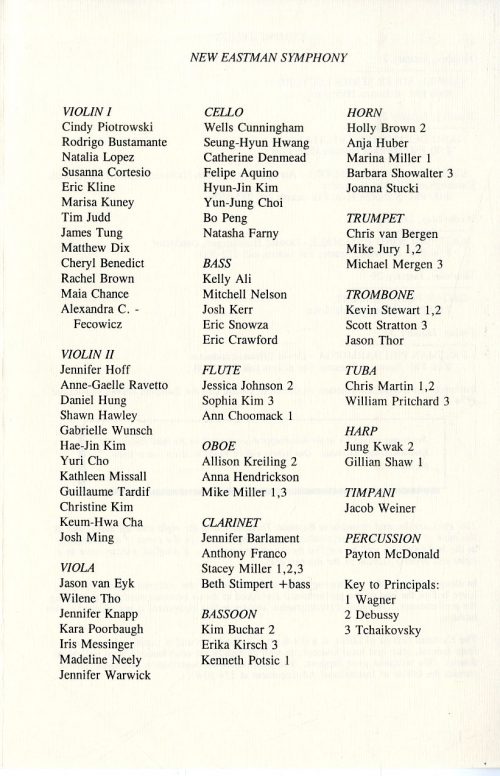

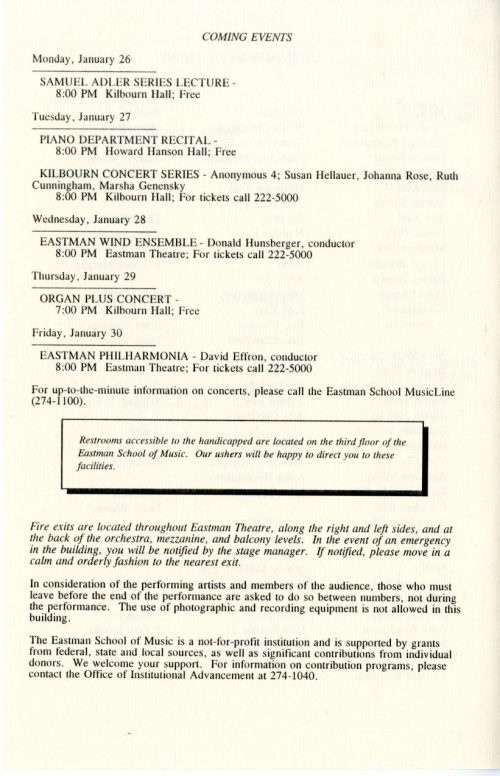

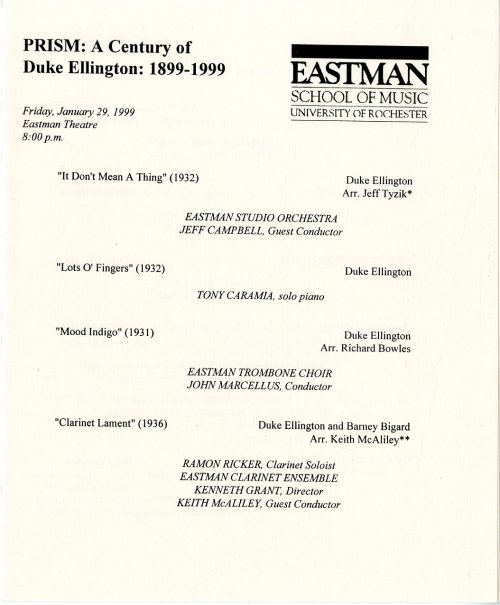

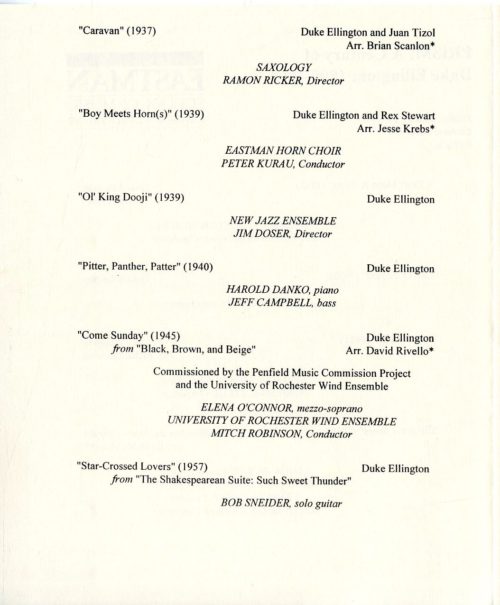

In this week’s “Weekly Dozen” we acknowledge the New Eastman Symphony, an entirely student-managed orchestra of graduate students that flourished for three academic years (1997-2000); a noteworthy concert in the PRISM series that paid exclusive tribute to the music of Duke Ellington; the celebration of the 80th birthday of Eastman alumnus William Warfield (year-year), BM ’42; the second of Eastman Opera Theater’s two (to date) productions of Debussy’s opera Pelléas et Mélisande; and a host of superlative student performances such as grace the Eastman concert calendar each week of the semester.

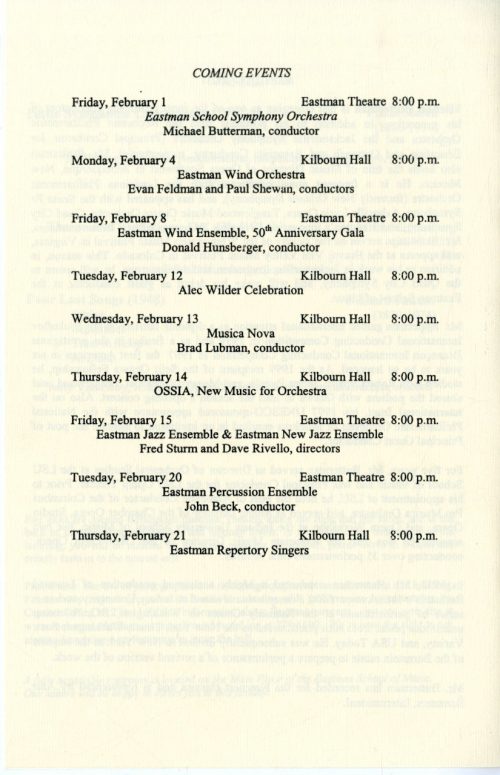

►January 25, 1998: New Eastman Symphony (Bradley Ludman, conductor)

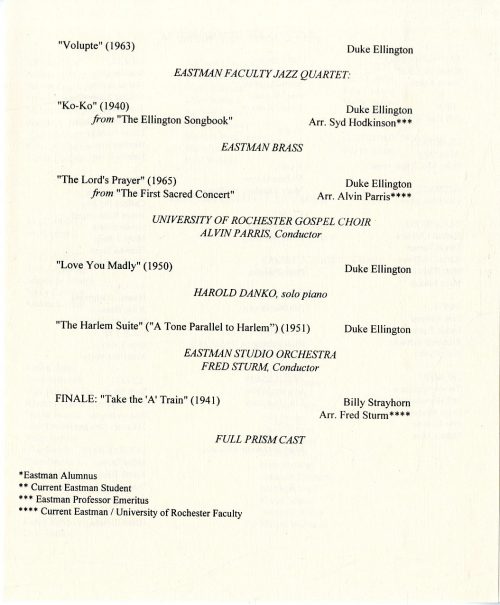

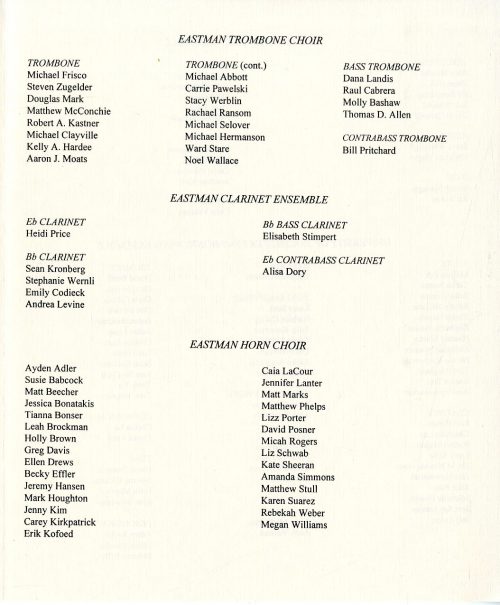

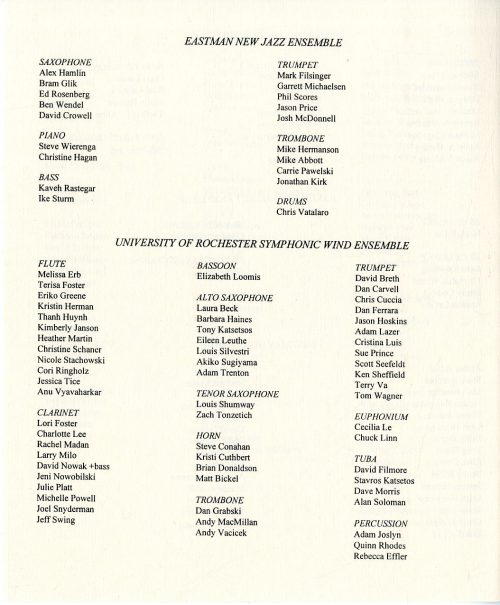

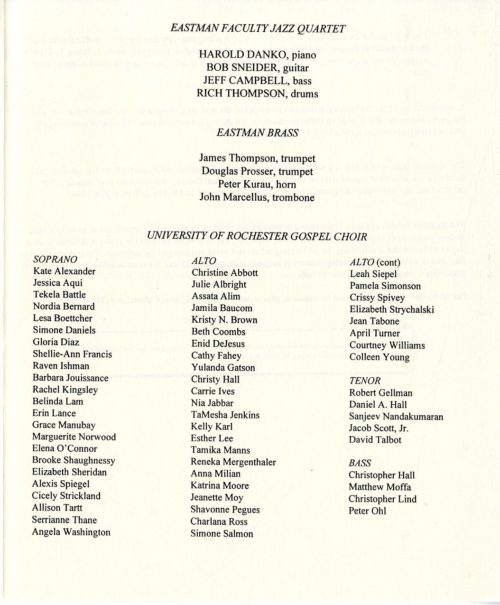

►January 29, 1999: PRISM: A Century of Duke Ellington: 1899-1999

►January 25, 2000: Paul M. Vasile (piano)

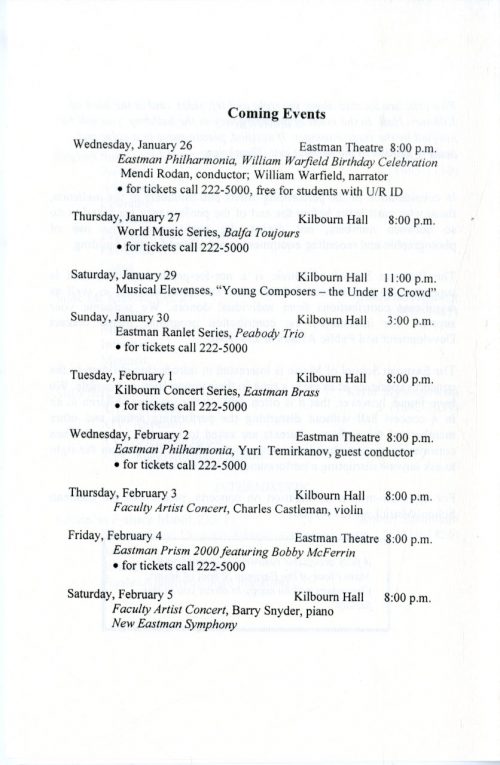

►January 26, 2000: Eastman Philharmonia/William Warfield 80th Birthday Celebration

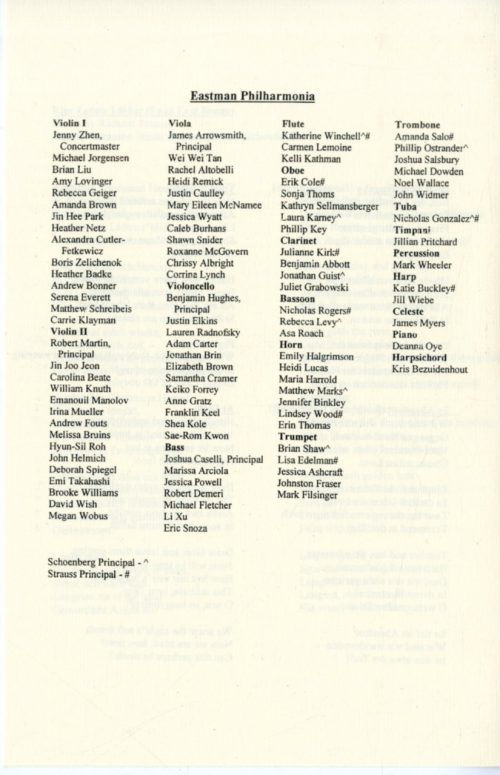

►January 30, 2002: Eastman Philharmonia (Donald Hunsberger and Michael Butterman, conds.)

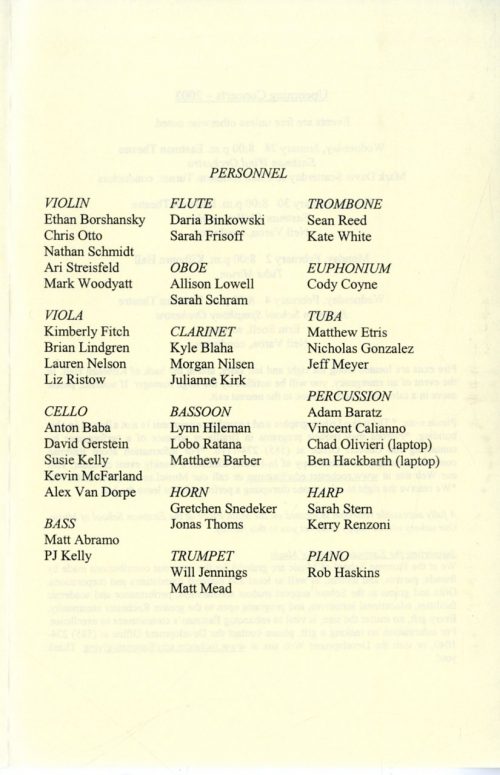

►January 26, 2004: OSSIA (Heather Gardner and Vincent Calianno, conductors)

►January 24, 2007: Rahim AlHaj (oud) in the World Music Series

►January 25, 2007: Zuzanna A. Szewczyk (collaborative piano) and Joshua Fein (baritone)

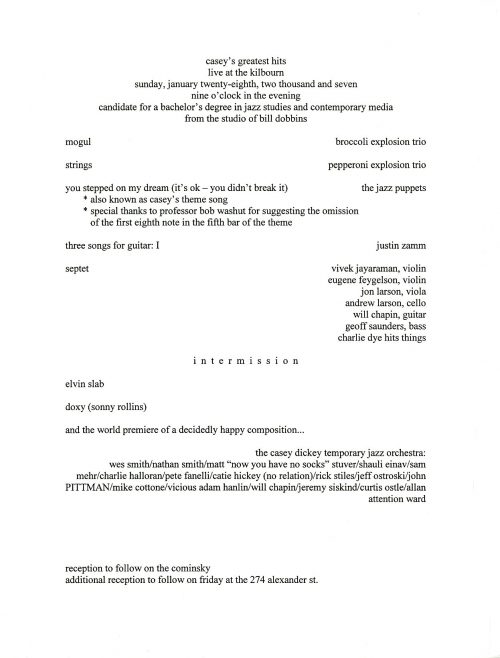

►January 28, 2007: casey’s greatest hits live at the kilbourn

►January 23, 25, 29, 31, 2009: Eastman Opera Theater presents Pelléas et Mélisande

►January 28, 2010: Harmony for Haiti: A Benefit Concert

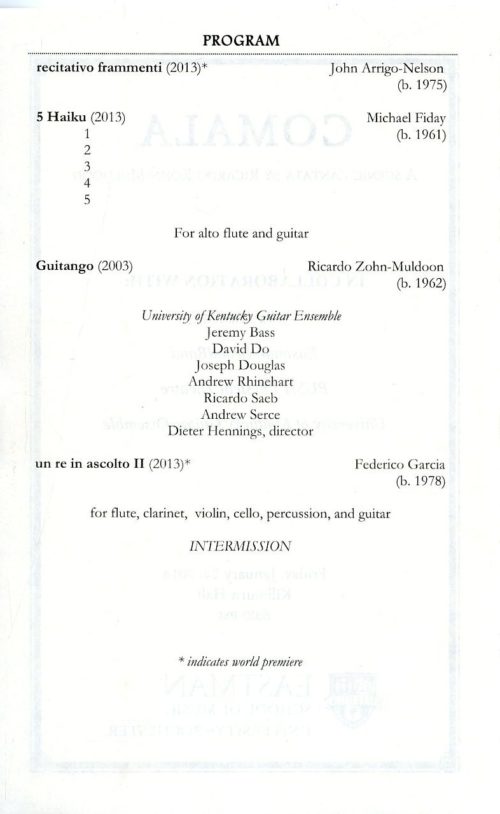

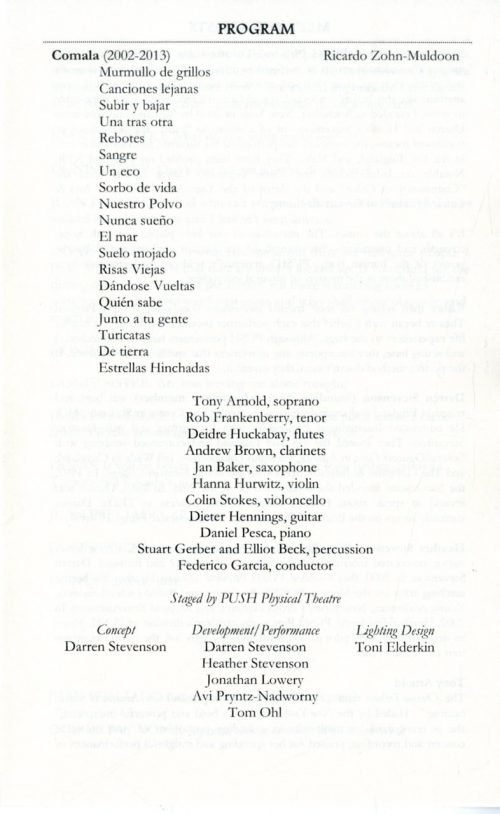

►COMALA: a scenic cantata by Ricardo Zohn-Muldoon, in collaboration with: Alia Musica; Eastman Broadband; PUSH Physical Theater; and, University of Kentucky Guitar Ensemble.