Published on Nov 15th, 2021

1924: Public debut of the Rochester American Opera Company

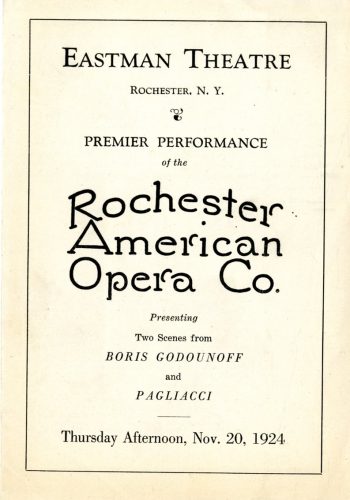

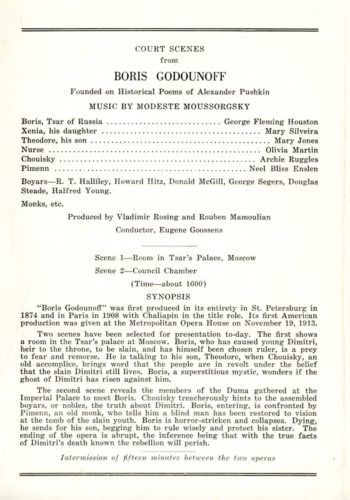

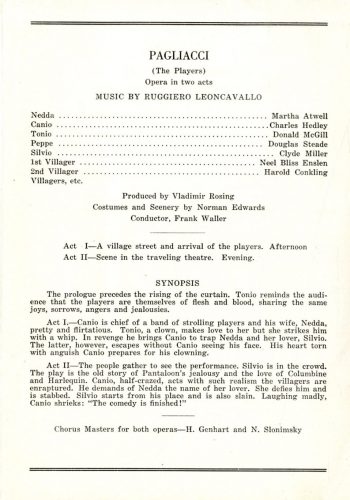

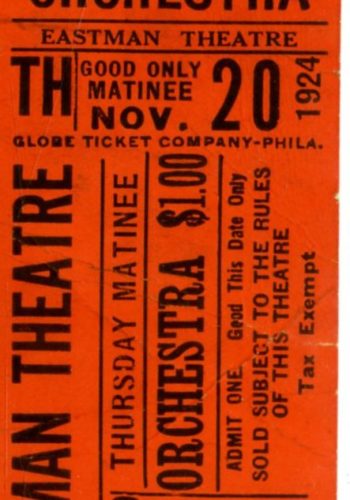

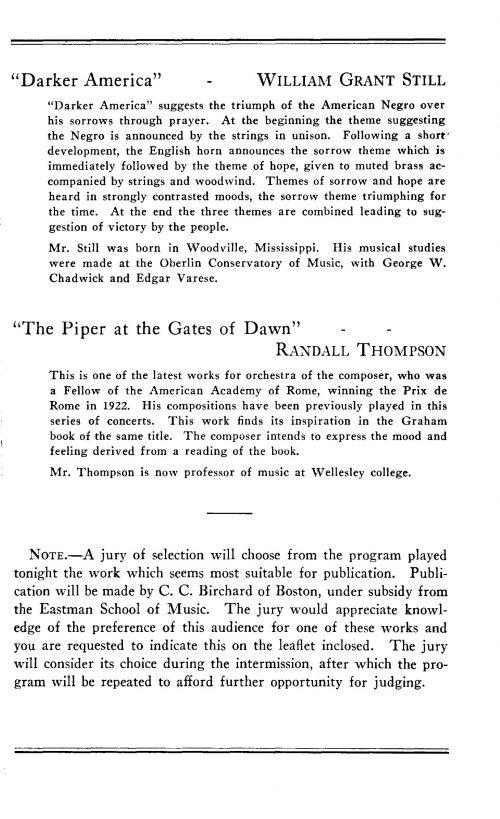

A previous entry in “This Week at Eastman” (week of November 1st/7th) drew attention to the Rochester American Opera Company, a fledgling troupe that was founded within the walls of the Eastman School of Music. Ninety-seven years ago this week, on November 20th, 1924, the Rochester American Opera Company made its public debut with a Mussorgsky/Leoncavallo double bill in the Eastman Theater, specifically, two acts from Boris Godunov and then I Pagliacci (in its entirety). That initial public performance represented the culmination of one year’s strenuous training on the part of the company’s members. It also represented the realization of a dream of the company’s founder-director, Vladimir Rosing, a Russian-born tenor and operatic director. In chronological time, the endeavor would last six seasons, from 1924/25 through 1929/1930. The story is an enthralling one, for while the sources are limited, they do give us to understand something of the spirit of innovation and experimentation that flourished in and around the Eastman School in the 1920s.

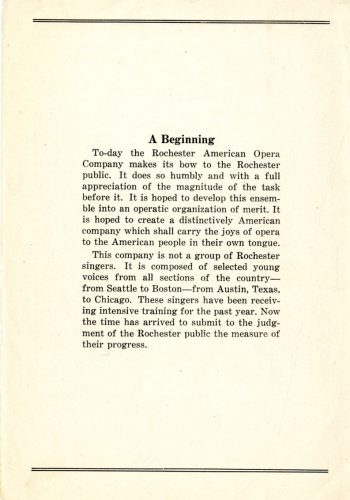

It had been Rosing’s dream when first meeting George Eastman to launch a native American opera company in the United States. To summarize, twelve singers would be awarded scholarships for 1923-24; those twelve would constitute a corps of artists in training who would eventually populate an opera repertory company. The class of twelve singers was soon expanded when in 1924 the Eastman School announced that four additional scholarships would be awarded. Plans for the 1924-25 season included production of three complete operas, together with the continuing presentation of scenes. Finally, in November, 1924 the Eastman School announced the formation of the Rochester American Opera Company, to be directed by Rosing, who maintained that the company’s chief aim was that it should be a truly American opera company, striving to bring opera to a wider segment of the U.S. public. To that end, the company would be comprised exclusively of American singers, and all performances would be sung in English.

Rosing defended English-language operatic performance in a 1926 interview. “America will never develop a great operatic public until we have companies, both touring and resident, carrying opera in the native tongue to all sections of the country . . . It is proper and fitting that we have great international companies singing opera in the original tongue, but it is equally important if we are to develop a large public for this form of stage entertainment, that the people have an opportunity to hear the master works sung in their own language.” Elaborating also on his ideas of production, he said: “We have developed a company in which we have tried to avoid the ‘star system.’ An artist may have a leading role one week and a minor part the next, as it is in the Moscow Art Theater. Principals are selected for their dramatic as well as their vocal fitness. I believe that the dramatic side should receive as much attention as the musical side in the performance of opera. The principals of the cast should make characters of their roles; the chorus should be as adequate in dramatic action as the principals, rhythmic action to music should constantly accompany the singing. Action and music should be synchronized to give both their greatest value.” (Rosing was quoted in the article “Rosing staunch ally of operas sung in English,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, June 27, 1926.)

A further hallmark of the company would be the promotion of Rosing’s concept of opéra intime, a style of operatic production characterized by simplification: opera staged in smaller theaters with reduced orchestra, simplified scenery, and without the operatic chorus, but with the dramatic aspect of the roles given equal attention with the vocal performance. Rosing had developed the concept during his years in London, England, where he had directed an opera troupe formally known as Opéra Intime. Finally, some lines that could very well serve as the company’s mission statement were published in Musical America, in the issue of March 19th, 1927: “It is Mr. Rosing’s contention that the dramatic side of opera should be stressed as well as the lyrical, and effort has been made to create a group of ‘singing actors’ who could present standard operas in English, well sung and well acted, and produced with economies that bring the admission prices within the grasp of the average theater-goer. It is no part of the Rochester Company’s plan to attempt competition or to invite comparison with established organizations and their artists of international fame, but to try to reach a new public which has hitherto found opera too expensive a form of stage entertainment and which is indifferent to it when sung in a foreign tongue.”

There was more or less a definite shape to the company’s crest and turns of fortune. Following its public debut in November, 1924, the company scored several local successes over the next two seasons. Rosing then gave up his executive work running the school’s opera department so as to concentrate full-time on direction and production. The company launched out on tour in both the U.S. and Canada, and in 1927 turned fully professional with the financial assistance of several backers, severing its administrative connections with the Eastman School and re-forming itself under the name the American Opera Company in its aspiration to become a truly national organization. The company’s headquarters were re-located to Chicago. Over the next three seasons, the company scored yet new milestones; funding was sought for independent status; there were inter-company marriages; and most notably, the company performed before the President and Mrs. Calvin Coolidge during a Washington, D.C. engagement.

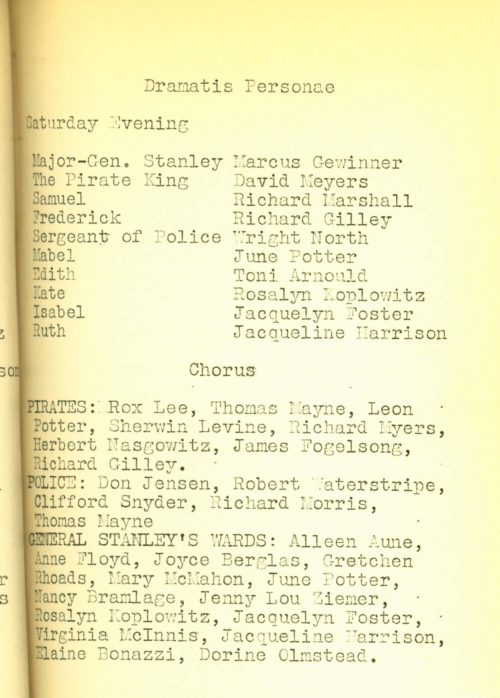

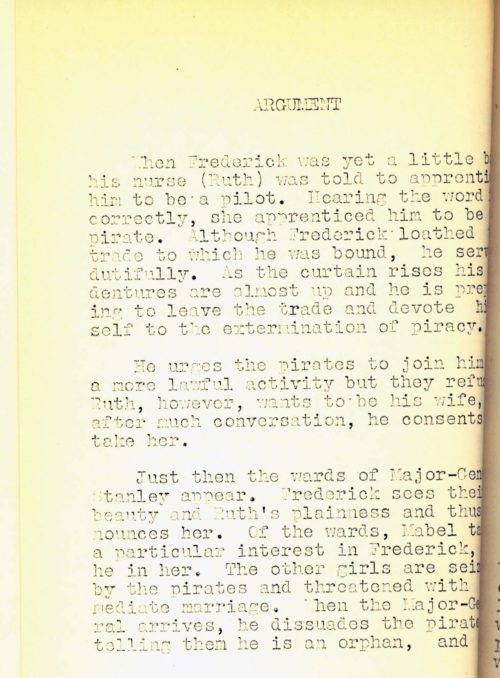

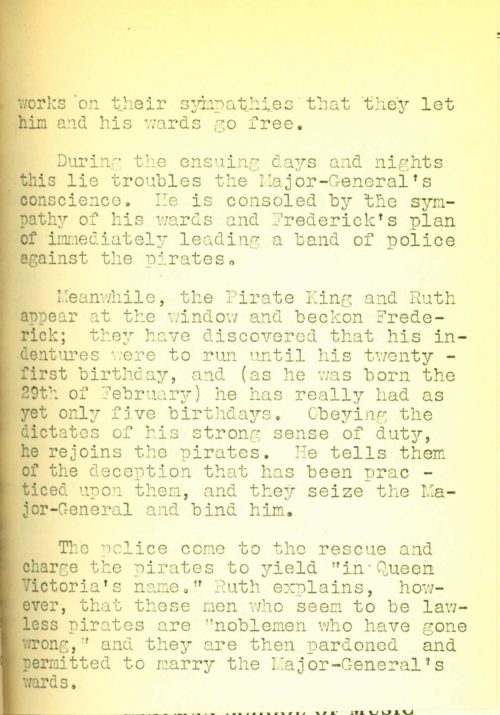

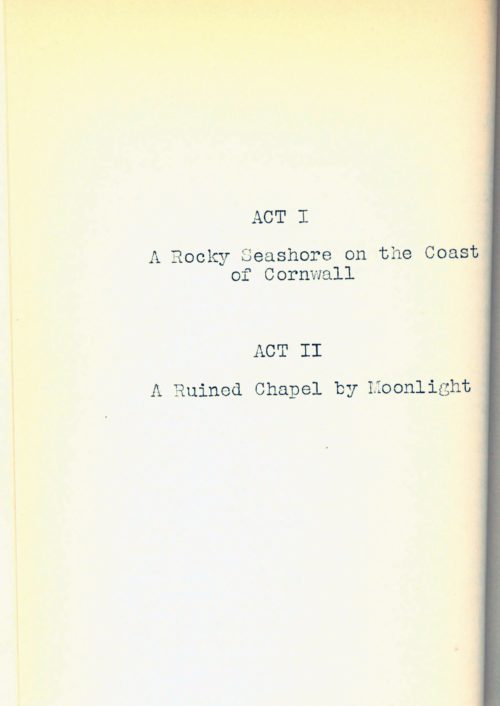

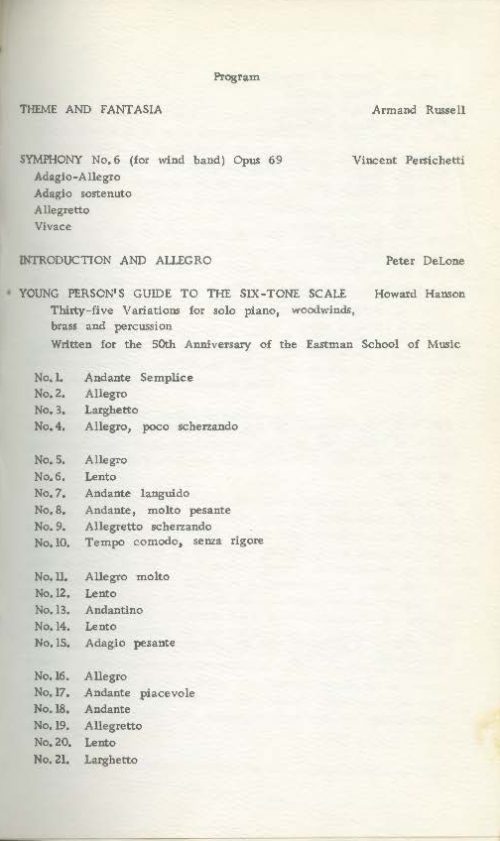

►Printed program and ticket stub. Local History Reference file.

► Press articles. Rochester Scrapbooks.

However, as history has recorded, the decade of the Roaring Twenties came to a crashing end (no pun intended) with the Great Crash on October 29, 1929 (known ever since as Black Thursday). The ensuing Great Depression left no aspect of American life untouched, and the Depression was to account for the beginning of the company’s end. As was reported in the Rochester Democrat & Chronicle (“America Opera to skip year”) on June 26, 1930, “Uncertain conditions in the musical field have persuaded the management of the American Opera Company to abandon plans for a tour next season, and the company will mark time until the season of 1931-32.” Citing a decline in subscriptions in a number of cities, the producers believed that a year’s lay-off would save money and would permit the company to begin the following season on a stronger financial footing. “If the ensemble can be held together, if its influential friends can be kept interested and, most of all, if public demand returns to former levels, the company should have its best years ahead of it.” As things would turn out, those confident words were not borne out by reality, for a return to the stage did not materialize. The company was finished.

What to make of this opera company and its six seasons? What to make of Vladimir Rosing and his vision or his ambitions? The Rochester American Opera Company was perhaps a natural product of the ethos of the time: the confidence, exuberance, and innovation of the Roaring Twenties and the jazz age, at a time when the USA had only recently been tested at war and had seen its industrial might increase exponentially in going to the aid of war-torn Europe. It was a time when risks could be taken. Paul Horgan, one of the company’s original members and later a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner, summed up some of that ethos in a piece in Harper’s Magazine: “The American time was very happy for a renaissance. It was in the early half of the twenties. We were getting over the War and were still sensitive enough to use our imaginations. The arts seemed to be a happy outlet for that future civilization we were going to have, in which there would be no more killing and exhausting of a whole race. The first step towards the new Golden Age was culture, and instant culture. It was the time of Babbitt, and everyone remembers Babbitt’s most charming trait, which was his receptivity to proposals that involved doing some new and honorable and hopeful with money.” All in all, it was an interesting time and an interesting endeavor. Perhaps the most fitting way to remember the Rochester American Opera Company is in the words of Quaintance Eaton in a feature article in Opera News (1971): “Rosing and his American Opera Company were, it seems way ahead of their time.”

A word about the sources

The challenge in recounting the story is the dearth of sources. All of the principals are deceased, and few of them published accounts of their own, nor left any personal papers that can be studied. The Eastman School retained basically none of its administrative papers of the 1920s, thereby accounting for a large gap in the archival record. No recordings nor films of the company’s activity are known to be extant. Nevertheless, the many contemporaneous press accounts that are preserved in the Sibley Music Library’s sequence of Rochester Scrapbooks, as well as the more comprehensive microfilm holdings at Rochester Public Library, constitute a rich source of reporting. The journal Musical America carried news of Rosing’s company from its earliest days, occasionally publishing photographs to supplement its reporting. In 2016, the Sibley Music Library received the gift of the Maria Silveira Reep Collection, which for the first time brought photographic documentation of the company into RTWSC; previously, press reportage and a 1925 cast photo of Carmen had been the only photographic holdings.

►Photos. The Maria Silveira Reep Collection.

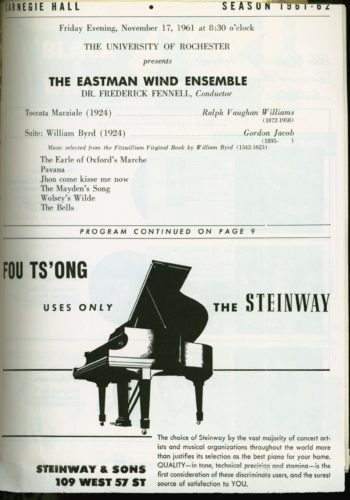

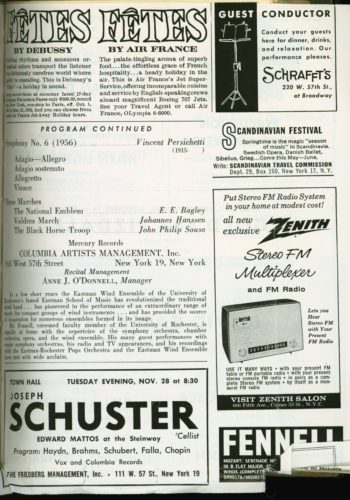

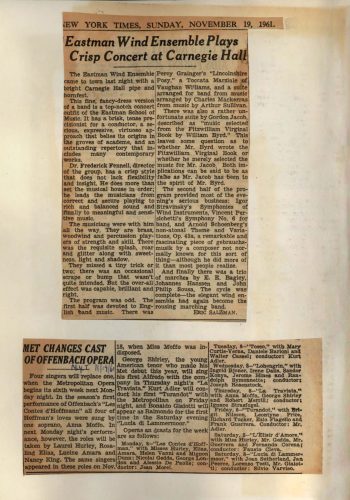

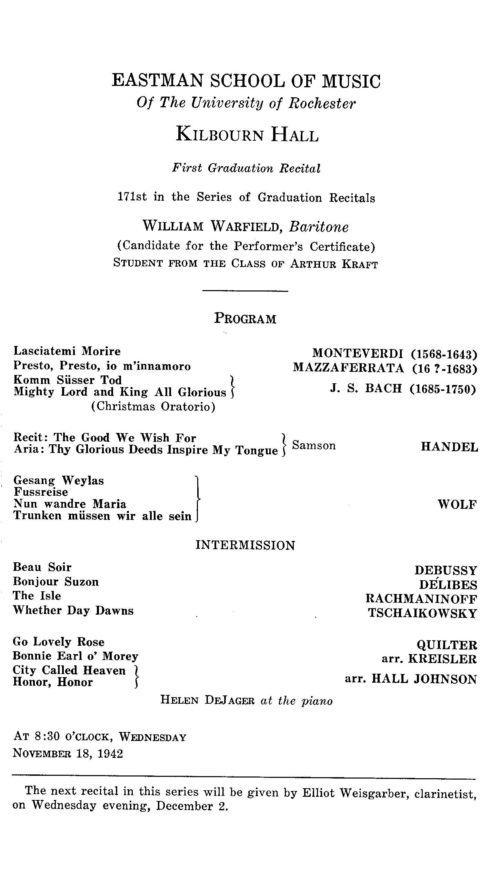

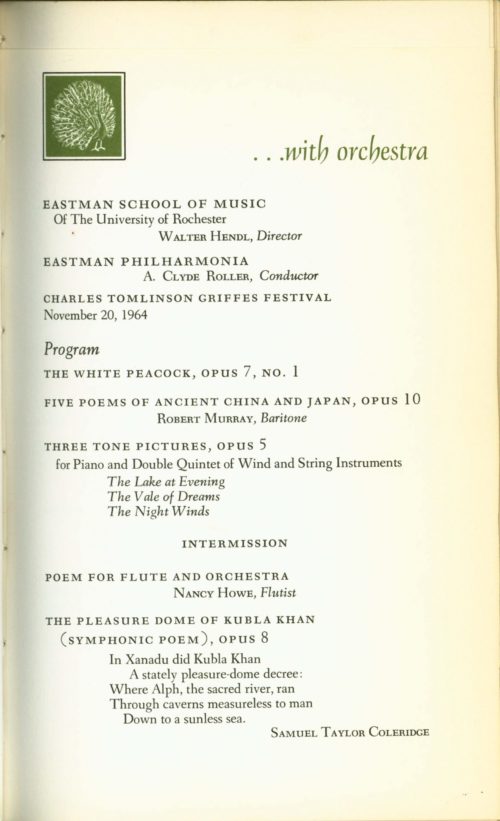

1961: Eastman Wind Ensemble at Carnegie Hall

Sixty years ago this week, on November 17th, 1961, the Eastman Wind Ensemble gave a concert at Carnegie Hall, its very first engagement in that august venue. Since then the Wind Ensemble had performed on numerous occasions in New York City. In the fall of 1961 the Wind Ensemble had just begun its tenth season and had been particularly active making commercial recordings on the Mercury Records label. Altogether, there would be nearly two dozen separate recordings by the time Frederick Fennell completed his ten years as director of the EWE.

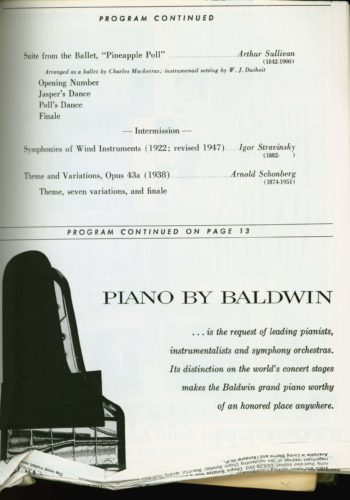

The Carnegie Hall program represented tried and test repertory, for all of the works on the program with the sole exception of the Pineapple Poll music by Arthur Sullivan had been recorded by the EWE for Mercury. (While not yet having recorded the Sullivan, the Wind Ensemble had previously performed it twice.) The concert was favorably reviewed in the pages of The New York Times.

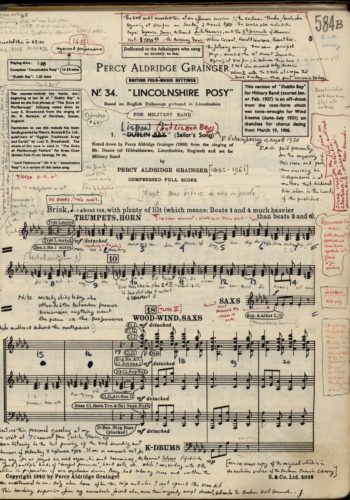

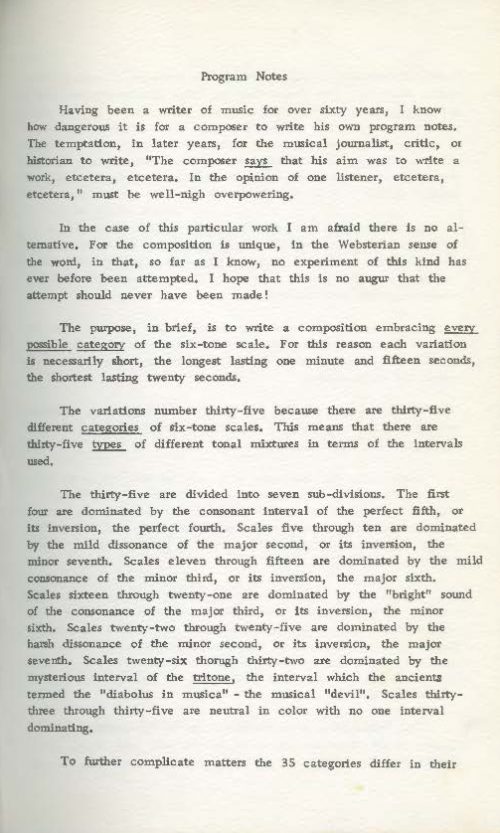

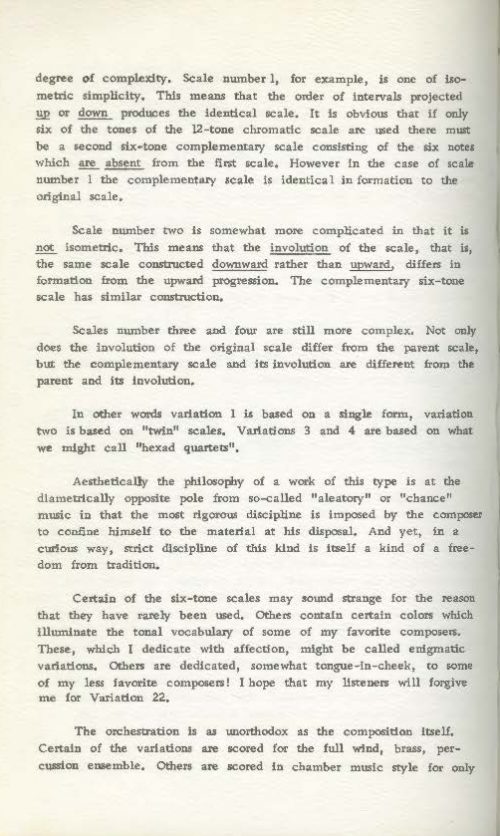

The programming of Lincolnshire Posy was especially significant, given that it was one of Frederick Fennell’s heartfelt favorite works to conduct, and also given that he had met the composer personally and whom he held in very high esteem. Maestro Fennell’s conducting score of Lincolnshire Posy is copiously marked up and annotated in the typical Fennell manner; the score’s first page of music is displayed here.

1961-62 would be Maestro Fennell’s last season as EWE conductor, and building on its first decade of success, the Wind Ensemble would go on to many more milestones both at home and around the world. The story of EWE achievement will be tracked in “This Week at Eastman” as the Eastman Centennial year marches forward.

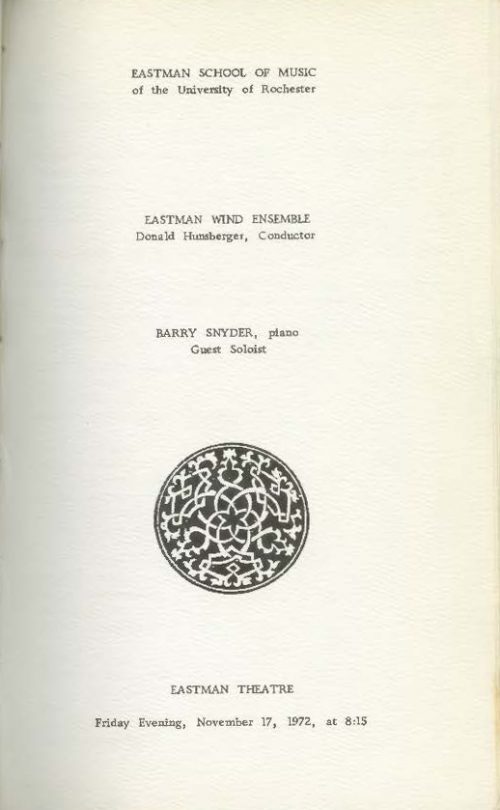

1962: Eastman Philharmonia at Carnegie Hall

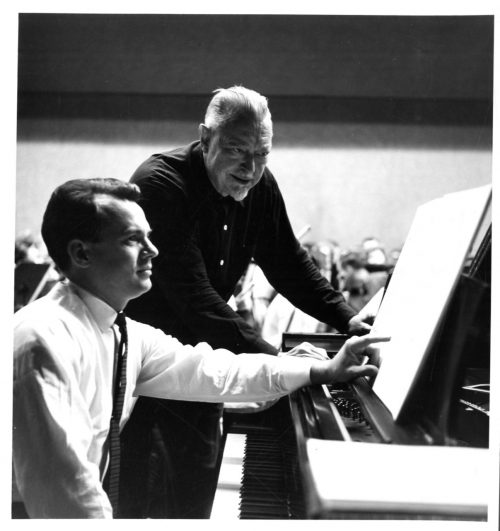

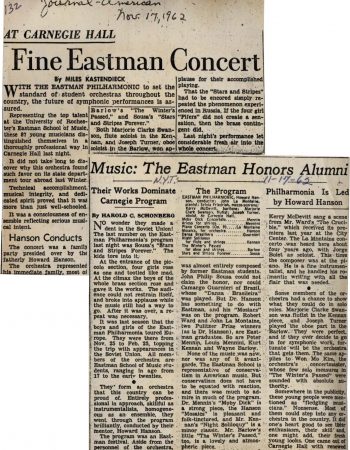

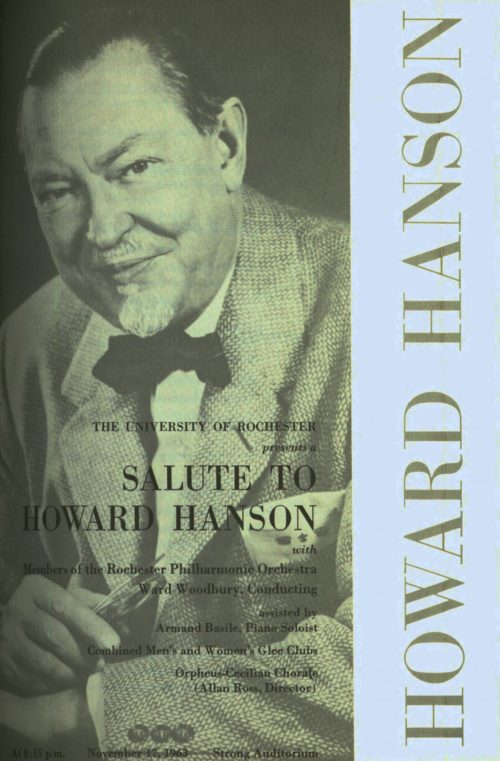

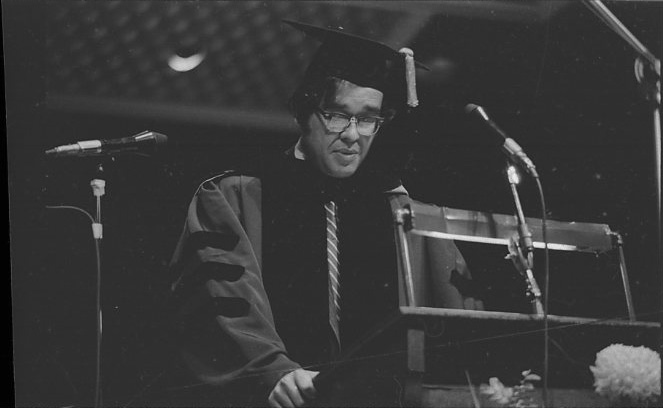

Fifty-nine years ago this week, on November 16th, 1962, the Eastman Philharmonia gave a concert in Carnegie Hall, following exactly one year after the Eastman Wind Ensemble’s first Carnegie Hall performance. The Eastman Philharmonia was just then in its fifth season, having been founded by Hanson in 1958, and was scoring one success after another. Already in the first season Hanson had taken the orchestra on run-outs to Atlantic City and to Buffalo. In the spring of 1961 the orchestra had performed in Washington, D.C., and in the winter of 1961-62, the orchestra had undertaken its landmark European tour. Before Hanson’s retirement, he would take the Eastman Philharmonia out of town once more, to an engagement at the 1964 New York World’s Fair.

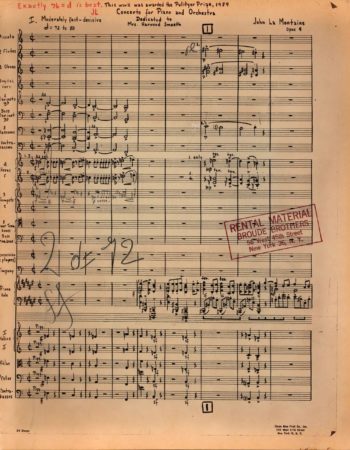

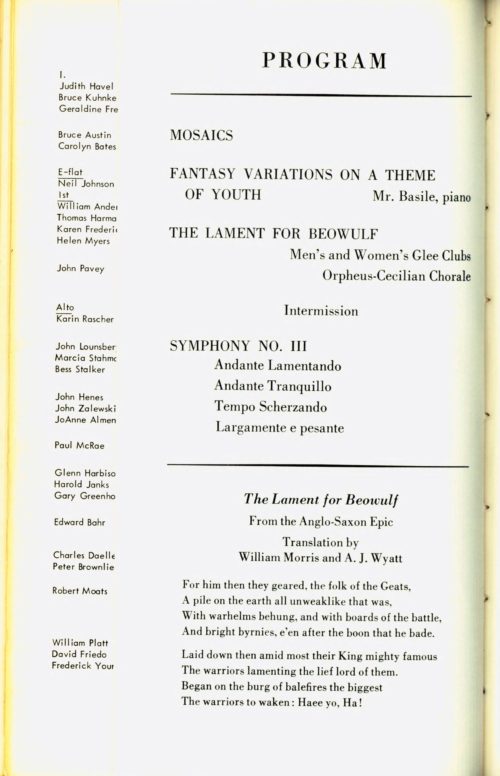

For the Carnegie Hall concert Hanson had chosen a program of music almost entirely by Eastman School alumni composers. Two of the composers—Robert Ward and John La Montaine—were represented by works which had been recognized with the Pulitzer Prize. The most substantive work on the program, from the standpoint of duration, was Mr. La Montaine’s Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, opus 9. The work had been commissioned by the American Music Center for the National Symphony Orchestra under a grant from the Ford Foundation. This Concerto ultimately proved to be the composer’s first of four concertos for piano and orchestra. Mr. La Montaine was a gifted pianist in his own right; in 1965 he would return to Eastman as soloist in the Concerto at the Eastman School’s annual Festival of American Music. When Mr. La Montaine had won the Pulitzer Prize for the Concerto in 1959, he had been the Eastman School’s second composer-graduate to have been so honored. For the record, the Eastman School’s Pulitzer Prize-winning composer-graduates have been the following:

- Gail Kubick, 1952 (BM ’34)

- John La Montaine, 1959 (BM ’42)

- Robert Ward, 1962 (BM ’39)

- Dominic Argento, 1975 (PhD ‘57)

- George Walker, 1996 (DMA ’56)

- Kevin Puts, 2012 (BM ’94, DMA ’99)

As regards other works on the program, Howard Hanson’s Mosaics was still a new work, having been composed in 1958 on a commission from the Cleveland Orchestra. In the first few years the work had been performed by numerous orchestras around the country. That Hanson had used this opportunity to promote one of his own works was not unusual, for he had routinely conducted his own music in Eastman School orchestral concerts both at home and on the road. (The programming for the Eastman Philharmonia’s 1961-62 European tour had included his Symphony no. 2 (“Romantic”) and his Elegy in Memory of Serge Koussevitzky.

Robert Ward’s opera The Crucible, represented on this program by excerpts, had at once established itself in the American operatic repertory and had won the composer a Pulitzer Prize in the same year of its premiere. (For the record, The Crucible has been produced at Eastman three times in its entirety (1963, 1973, 1986).) It was significant that Hanson included four encores that he had conducted in the U.S.S.R during the Eastman Philharmonia’s tour. After the tour he had proudly shared the story, both in a printed article and during on-air interviews, of how enthusiastically Russian audiences had received Sousa’s march The Stars and Stripes Forever. (Hanson would surely have approved when that same march was named the U.S.A.’s National March in 1987 by an act of Congress and with President Reagan’s signature.)

In the years since 1962, the Eastman Philharmonia has performed in New York City on numerous occasions, including three more concerts at Carnegie Hall (1972, 1983, 1990) as well as concerts at Alice Tully Hall. More of the Philharmonia’s milestones will be observed and celebrated as “This Week at Eastman” continues its weekly march through the Eastman Centennial.

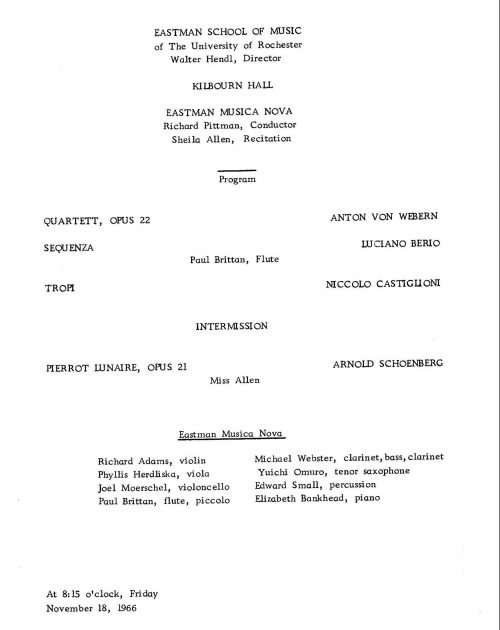

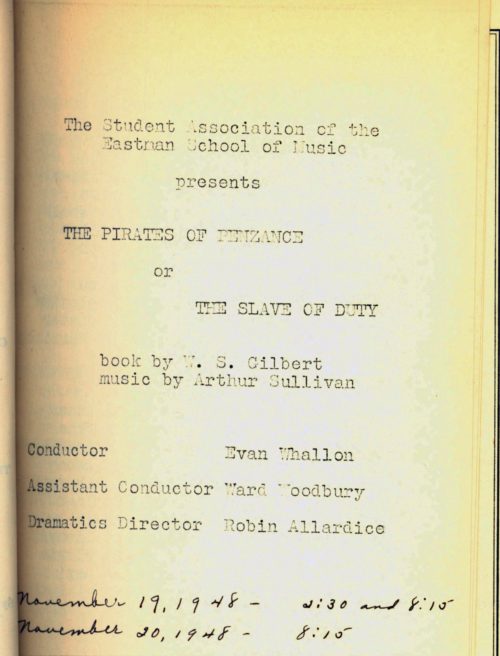

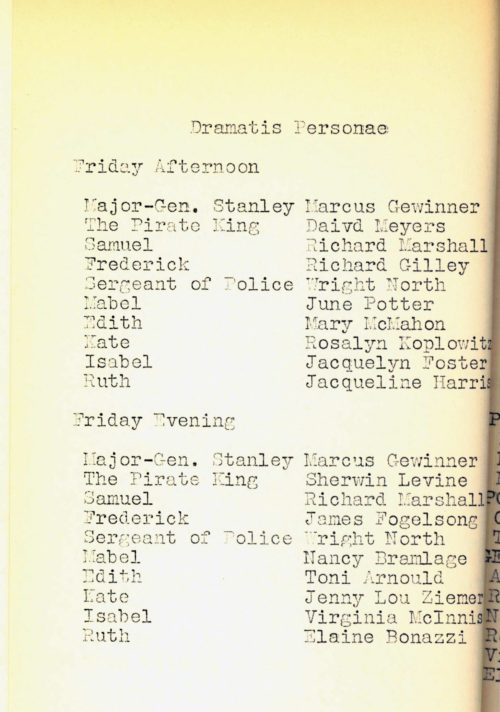

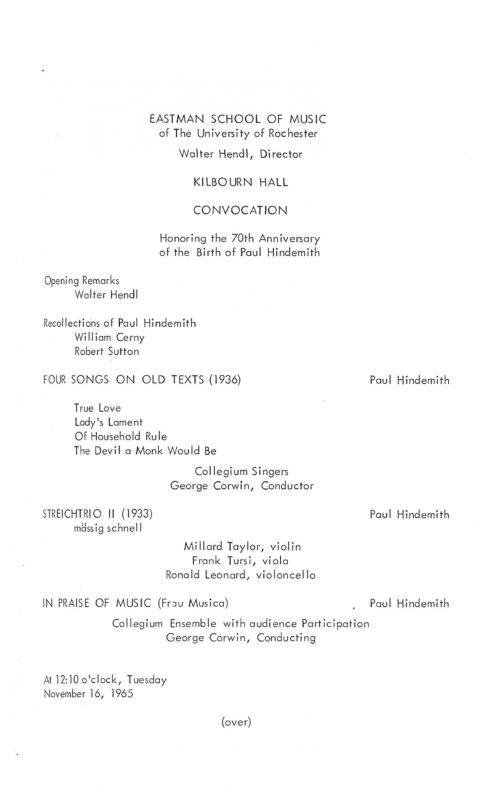

1966: Musica Nova public debut

Fifty-five years ago this week, on November 18th, 1966, Eastman’s Musica Nova made its public debut with a recital in Kilbourn Hall. Significantly, the performance represented the first public performance of Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire at the Eastman School. Other than a reading in Hanson’s collegium musicum in 1961, which served a purely pedagogical purpose, the Musica Nova performance in 1966 was the school’s premiere.

Musica Nova has continued to enthrall audiences in the decades since that time. It enjoyed a period of particularly sustained vigor under the direction of the late Sydney Hodkinson (served 1973-1998).

1970: Eastman Studio Orchestra public debut

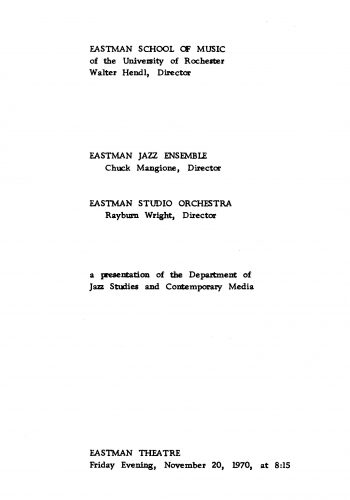

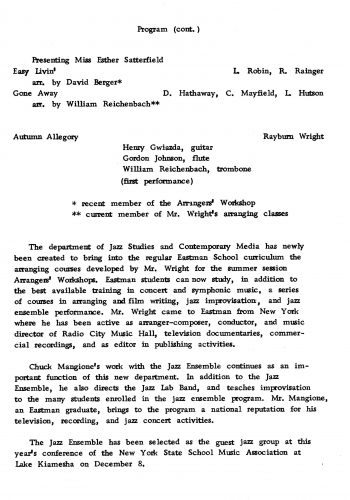

Fifty-one years ago this week, on November 20th, 1970, the Eastman Studio Orchestra made its public debut in a joint concert with the Eastman Jazz Ensemble.

The department of Jazz Studies and Contemporary Media was in its first academic year, having only recent been established and thereby bringing jazz studies into the Eastman School’s regular curriculum. Earlier in 1970, Eastman alumnus Rayburn Wright had been appointed to the Eastman faculty and thereafter relocated from New York City to Rochester. Mr. Wright had previously been involved with Eastman since 1959 in developing the arranging courses offered each summer under the auspices of the annual Arrangers’ Workshops. Under the newly founded department of Jazz Studies and Contemporary Media,

The Studio Orchestra was conceived as an all-volunteer (non-credit) group, comprised of the members of the Eastman Jazz Ensemble complemented by numerous additional players on strings, woodwinds, and harp. At its outset, the Studio Orchestra was believed to be a unique ensemble among schools of music in the U.S. Following on its 1970 public debut, the Eastman Studio Orchestra would quickly distinguish itself to such a degree that it would be invited to perform at the 1972 biennial meeting of the Music Educators National Conference.

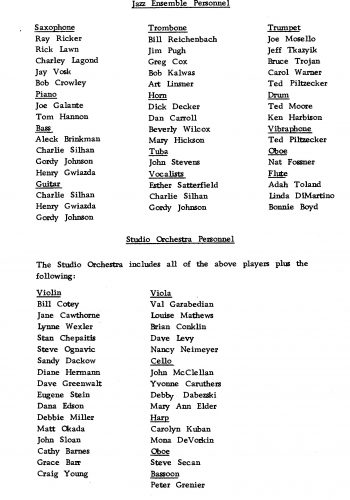

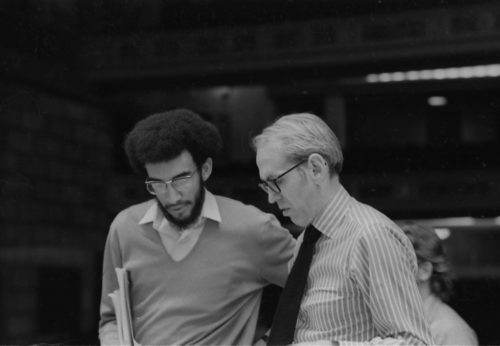

► Photos by Louis Ouzer. Master negative nos. R1041 : R1043

Printed Program.

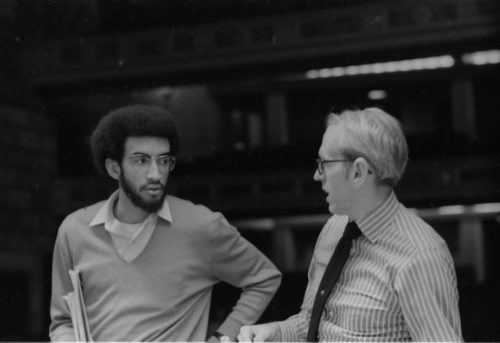

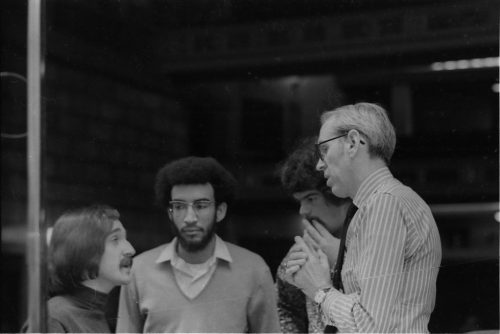

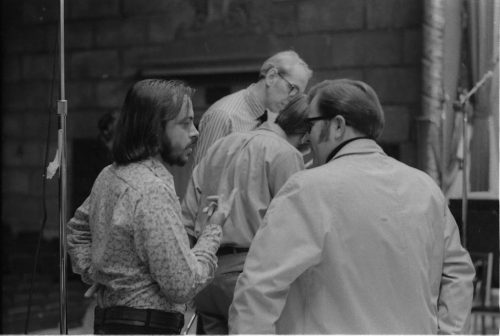

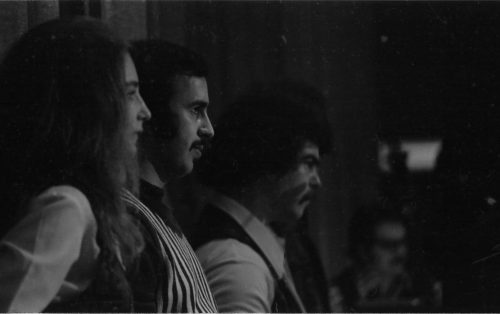

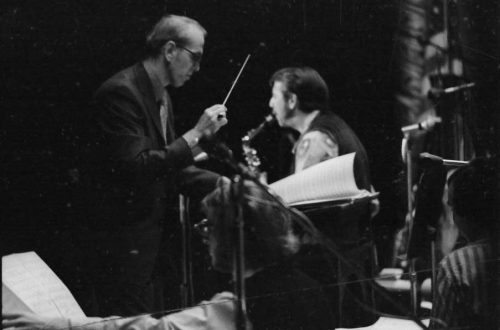

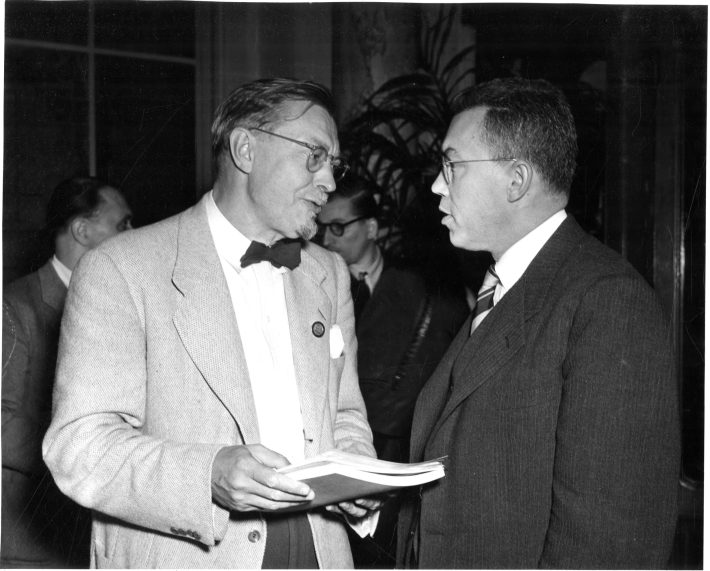

Pre-concert discussions between the principals in the Eastman Theater.

.

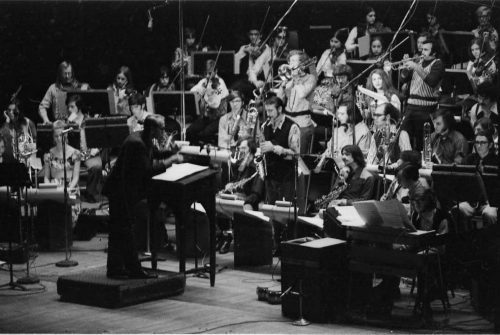

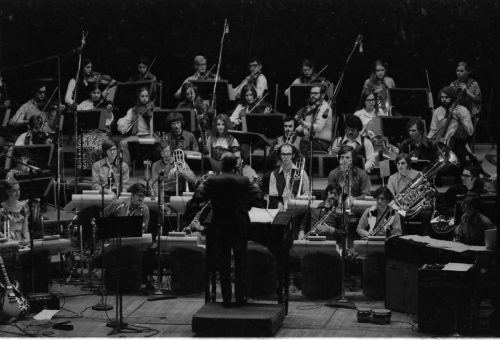

Director Ray Wright and Eastman student-performers on-stage in the Eastman Theater on the occasion of the Eastman Studio Orchestra’s public debut.

1984: Marie-Claire Alain Master Class

Thirty-seven years ago this week, on November 15th, 1984, French organist Marie-Claire Alain (1926-2013) gave a master class in Schmitt Organ Recital Hall. A noted teacher and scholar, she was much in demand for master classes on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Marie-Claire Alain was the younger sister of organist-composers Jehan Alain (1911-1940) and Olivier Alain (1918-1994). She had studied in the class of Marcel Dupré at the Conservatoire in Paris (as did Rolande Falcinelli (1920-2006), whose manuscripts the Sibley Music Library holds). She was particularly associated with the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, whose complete organ works she recorded three times. At the time of her death, Marie-Claire Alain bore the distinction of having been the most-recorded concert organist in the world.

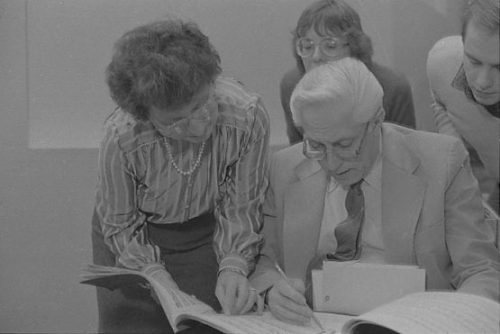

In these photographs by Louis Ouzer, Eastman faculty members Russell Saunders and David Craighead are both visible among Eastman students. Calling Eastman alumni! Were you in attendance that day? Please reach out and share your stories!

Organist Marie-Claire Alain works with faculty members and students of the Eastman School’s Organ Department in Schmitt Organ Recital Hall.