Published on Nov 1st, 2021

1926: Rochester American Opera Company in Kilbourn Hall

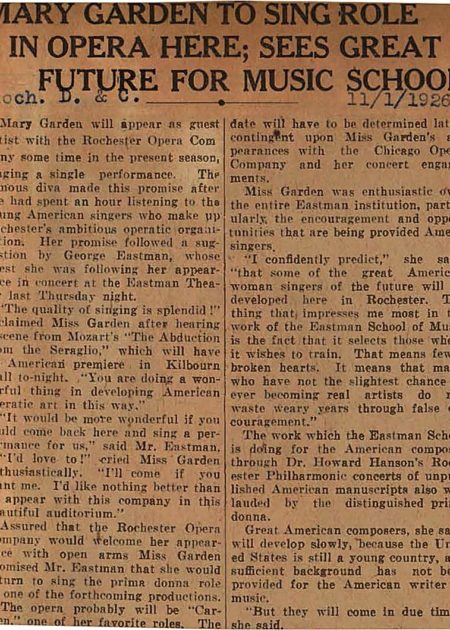

Ninety-five years ago this week, on November 1st through 6th, 1926, an ambitious Eastman-based group known as the Rochester American Opera Company performed each night in Kilbourn Hall, alternating performances of Mozart’s The Abduction from the Seraglio with Friedrich von Flotow’s Martha. The director was Vladimir Rosing, the musical director was Eugene Goossens, and the Eastman Theater Orchestra was conducted by Eugene Goossens (Mozart) and Emanuel Balaban (Flotow). The Rochester American Opera Company is today little remembered, but at that time it was a lively performing unit that provided Eastman’s voice and opera students with opportunities for professional exposure and experience while enrolled in their studies. ESM Historian Vincent Lenti has captured the story in one chapter of his 2004 volume; my comments here are based on reportage that was printed in the Rochester press and in the pages of Musical America.

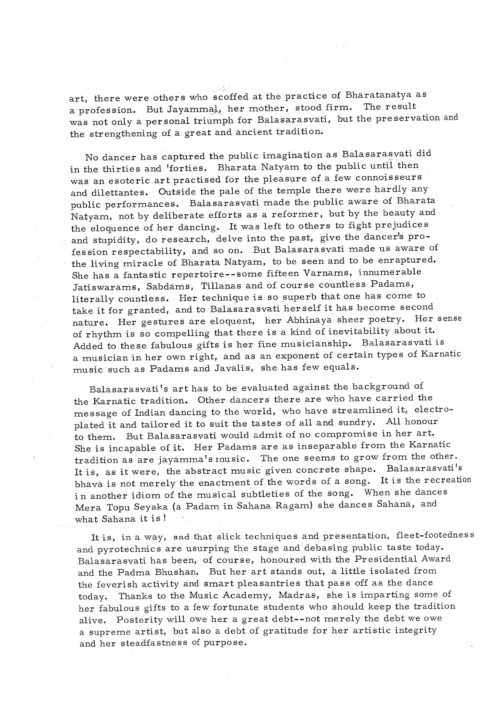

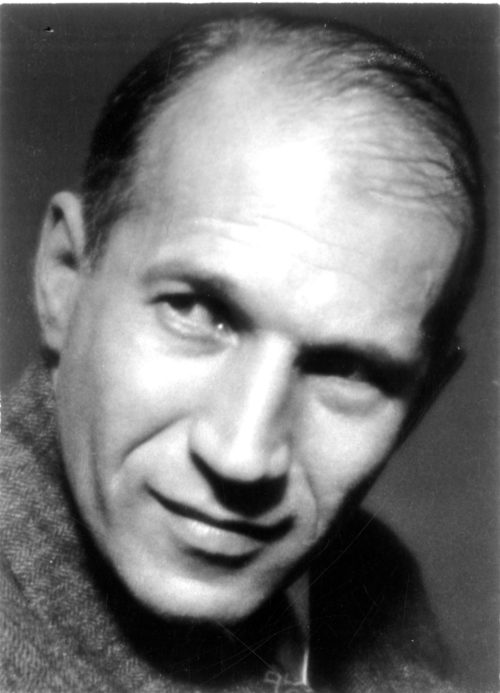

Just what was this Rochester American Opera Company? The company had been founded at the Eastman School in 1924 by Russian-born opera director and producer Vladimir Rosing (1890-1963), whom George Eastman had hired for the purpose of founding an opera department at his new music school. There are differing accounts as to when, and under what circumstances, Vladimir Rosing met Mr. Eastman and received his offer of employment (or whether he even met Mr. Eastman at all); one account holds that they met on-board a ship on the North Atlantic; however it actually happened, Mr. Rosing received the offer and arrived in Rochester in 1923 with a mandate from Mr. Eastman to organize an opera department. The “operatic” department, as it would be known at first, was launched that year with the announcement that twelve scholarships, each covering tuition fees and a $1,000/year living allowance, would be offered to eligible candidates, who were required to be U.S. citizens either by birth or adoption, and also to have completed sufficient study as to be vocally equipped for operatic performance. Mr. Rosing personally auditioned applicants in half a dozen cities (Rochester, New York, Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, and New Orleans) and then selected those who were to be admitted. Ten of the twelve available scholarships were awarded for that first year, 1923-24; those ten singers would be given the opportunity throughout the year to appear in public in scenes from operas, all selected by Mr. Rosing and prepared under his direction, thus affording them valuable performance experience. Two classes would be maintained in the opera department: an advanced class, comprised of those students making public appearances, and a class of less advanced students who would be promoted as their work merited. Students would be given daily! classes in ballet and rhythmic training so as to ensure physical conditioning and control; daily classes in mental training so as to develop powers of concentration, visualization, and control of emotions; and lessons in both vocal interpretation and dramatic training. In addition, students would be filmed with the aid of a motion picture camera to assist them in their mastery of the dramatic art.

This was all well and good, but Rosing’s plans didn’t stop with any mere opera department; he was all about building an opera company! As he had designed it, the opera department would serve as the training ground for a class of singers who would form the corps of a professional opera company at the Eastman School once they had been brought to proficiency. Moreover, that company would perform operas in English for comprehension by the wider listening public. And so, after training his students strenuously for all of academic year 1923-24, Rosing was ready to put them on the stage as the Rochester American Opera Company. The R.A.O.C. (my own abbreviation; I have not seen it called thus in the printed media) was formally rolled with a public performance on November 20th, 1924, and after local successes in and around Rochester in its first two seasons, the company was critically acclaimed by critics and the public alike during engagements in Washington, D.C. and in New York City in 1926 and 1927. The company’s second season, 1925-26, included a tour of Western Canada, thus possibly qualifying it for the distinction of the Eastman School’s first touring ensemble abroad. In the summer of 1926, the company completed a successful engagement at Chautauqua, concluding the season in a storm of applause and more favorable reviews.

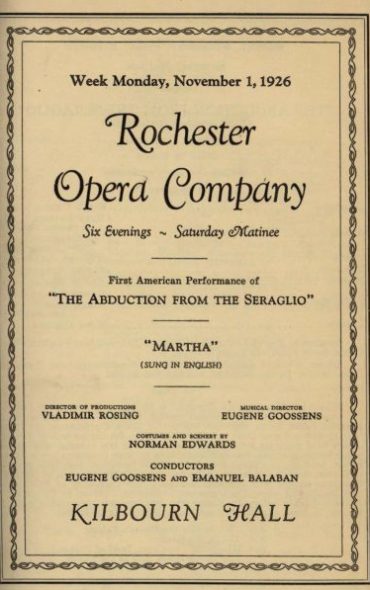

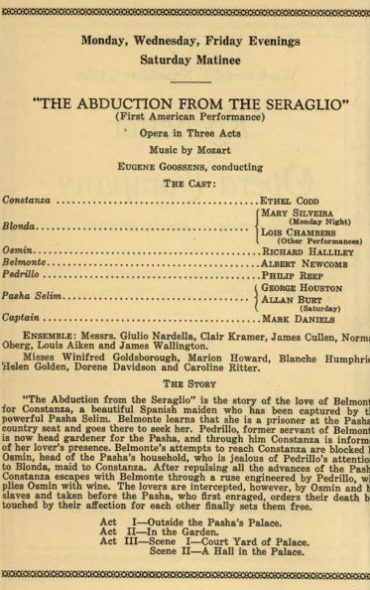

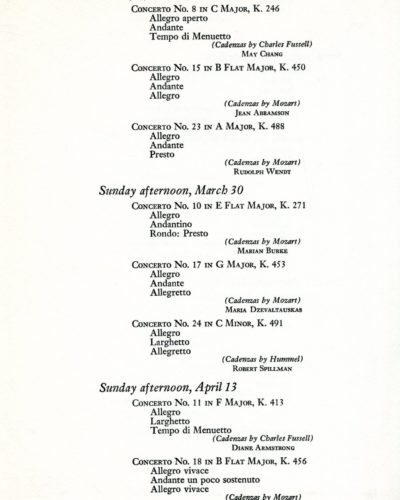

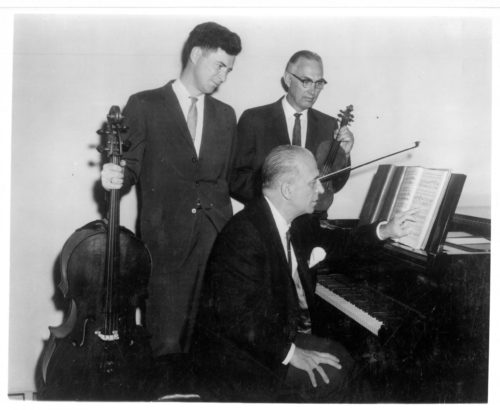

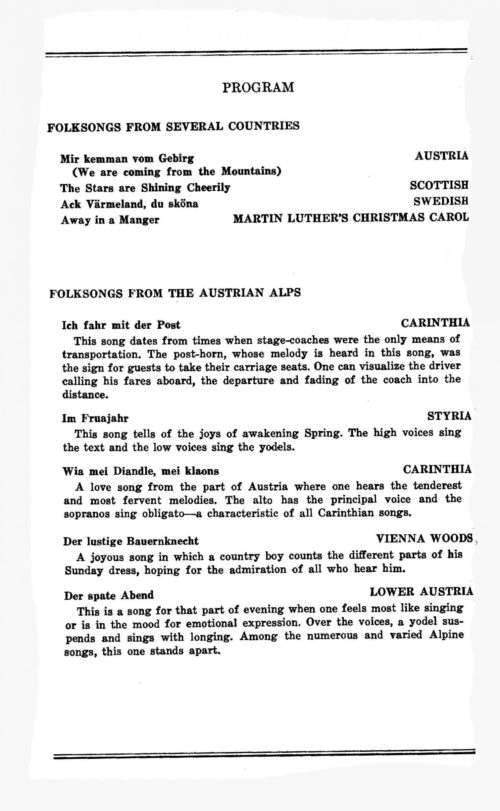

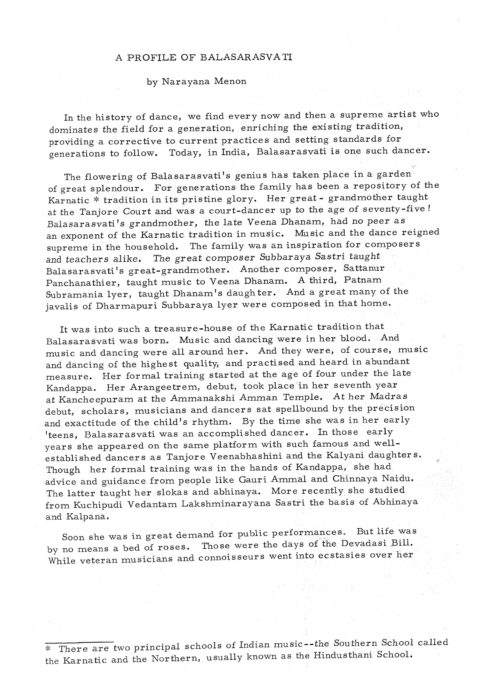

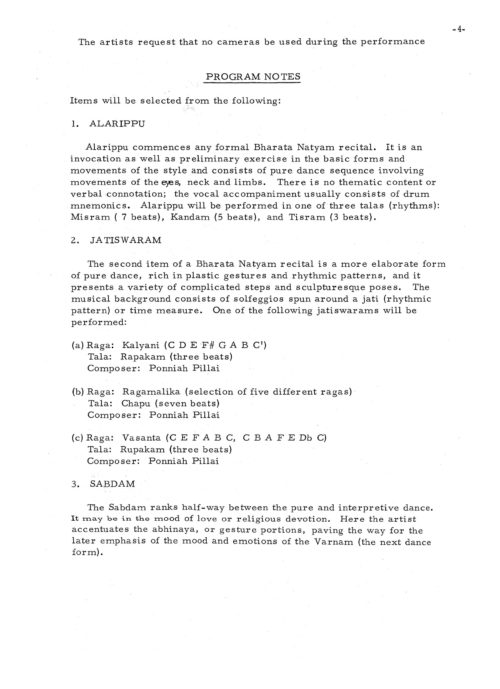

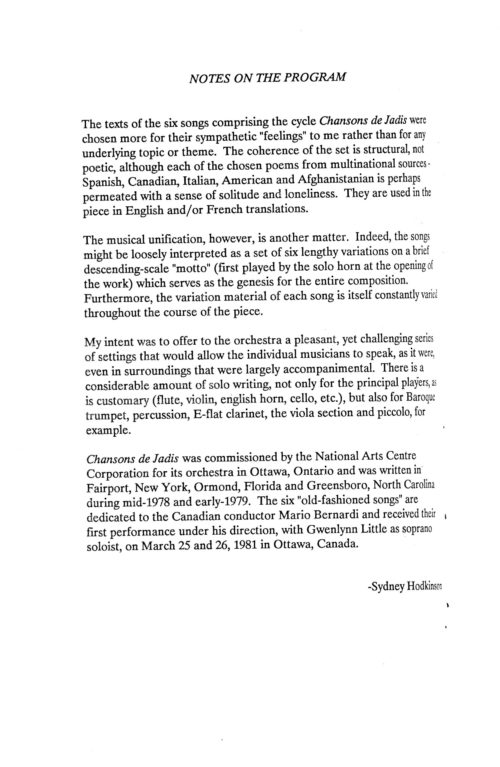

► Printed program for the week-long engagement in Kilbourn Hall, promoting the American premiere of Mozart’s opera The Abduction from the Seraglio.

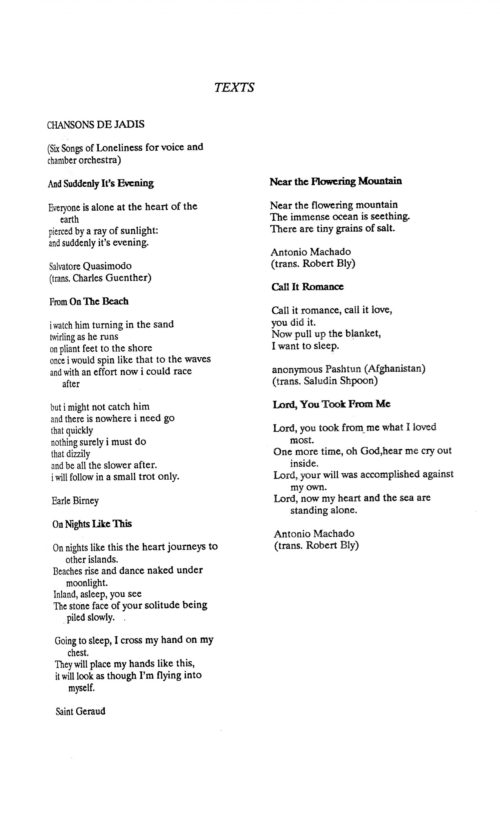

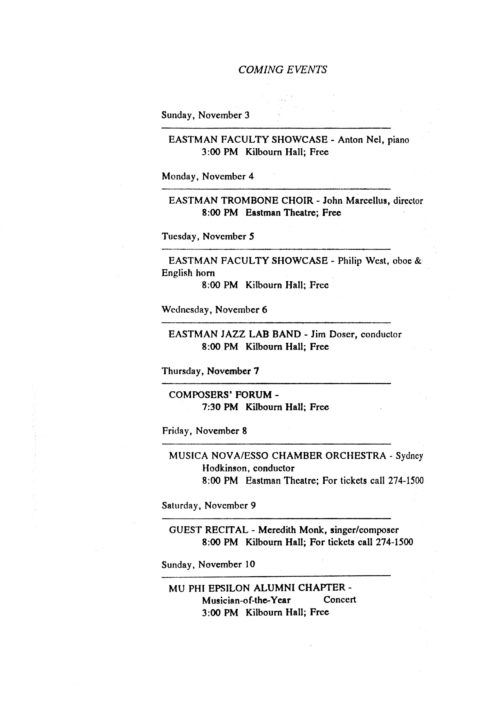

►Photo. Vladimir Rosing by Alexander Leventon, 1947. Alexander Leventon Collection.

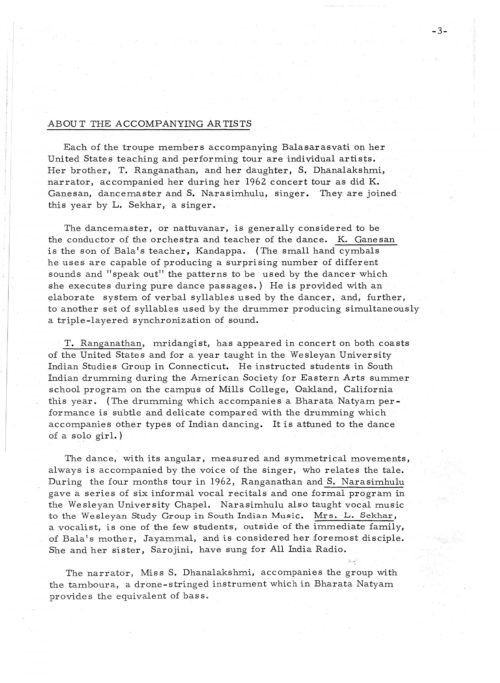

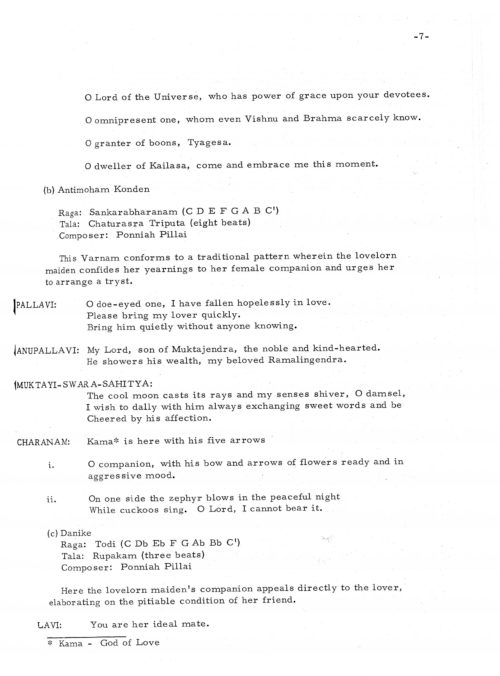

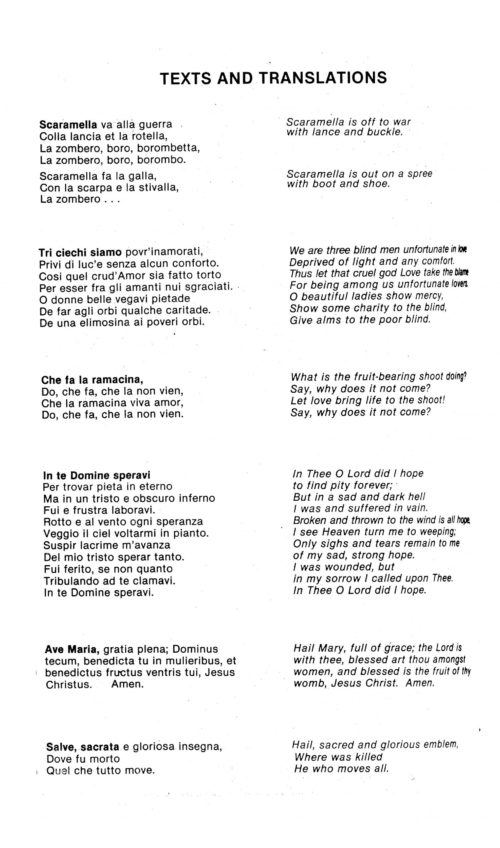

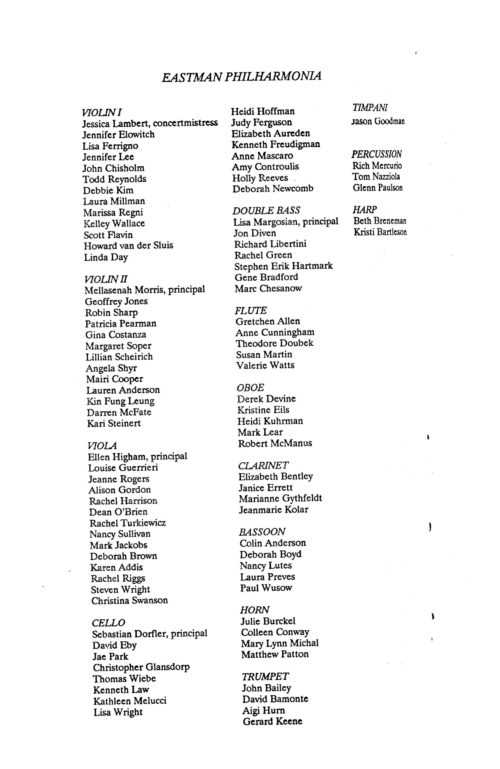

And so to November, 1926 and that week-long engagement in Kilbourn Hall. It began on the Monday evening with Mozart’s The Abduction from the Seraglio and continued the next evening with Flotow’s Martha. Thereafter, the two operas alternated throughout the week’s run, which included a Saturday matinée, i.e. Mozart on the evenings of Monday, Wednesday, Friday and then the Saturday matinée; Flotow on the evenings of Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday. Eugene Goossens was conductor for the Monday performance, and thereafter he shared the baton with Emanuel Balaban for the duration of the week. The casts of both operas are listed in the printed program uploaded here. The two photographs uploaded here are noteworthy in that they provide documentation of some of the earliest operatic staging in Kilbourn Hall. Director Vladimir Rosing espoused an artistic credo of opéra intime, according to which operatic performance was to be adaptable to smaller venues and by smaller troupes, and further, there should be no hesitation to dispense with choruses altogether. Minimalism was the key; hence, there is nothing elaborate about the staging. These photographs, which arrived in the Sibley Music Library as part of the personal collection of one of Rosing’s original Eastman company members, are the oldest extant documentation of what opera looked like on-stage at Eastman in the 1920s.

►Two scenes from Flotow’s Martha as staged in Kilbourn Hall by the Rochester American Opera Company

The week’s performances of The Abduction from the Seraglio were promoted in the printed program and in the pages of the local press as having been nothing less than the U.S. premiere of this opera. “First American performance of Mozart’s ‘Seraglio’” ran the headline in the Rochester Democrat & Chronicle on November 2nd, 1926. “A week of opera-giving by the Rochester Opera Company was started last night in Kilbourn Hall. The company gave the first American performance of Mozart’s opera ‘The Abduction from the Seraglio,’ an opera given frequently in Europe and not before this in our own land just because we have not had such organizations as is the Rochester Opera Company at hand to give it.” The claim that the Rochester production was an American premiere was significant then, and remains so today; this claim appears to have been little remembered today, but back in the 1920s, it could potentially have caused embarrassment if later found to have been erroneous. However, one consideration to be borne in mind is that Howard Hanson was now in his third year as Eastman School Director. So tightly did Hanson manage administrative affairs at school, and so zealous was his concern for the school’s reputation, that he would never have permitted the publication of such a claim if it had been groundless.

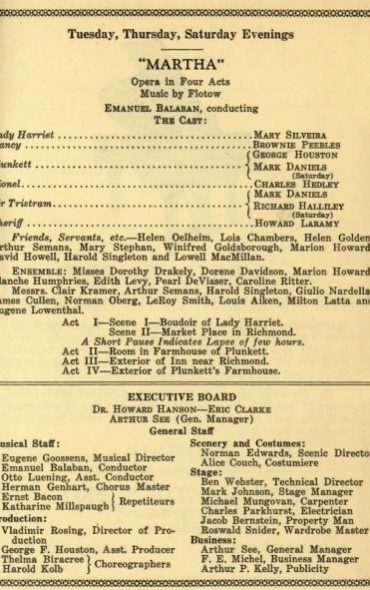

Altogether, that first week of November, 1926 was momentous for the R.A.O.C. for reasons above and beyond the success of the Kilbourn Hall performances. Announcements were made in the Rochester press of two exciting new developments: first, that the renowned Scottish-born soprano Mary Garden (1874-1967) would return to Rochester later that season to appear with the company; and second, that a permanent operatic chorus would be established in Rochester to assist the company. These announcements were exciting for what they underscored about the company’s development and progress. While Mary Garden was no stranger to the Rochester audience, having appeared here previously (and she was a personal friend of Mr. Eastman), her readiness as an established operatic star to appear in public with a fledgling opera company displayed her own confidence in the company’s abilities and standing. Meanwhile, the founding of a permanent chorus appeared to promise much for the company’s future productions. No amateur chorus, this, for the initial call for interest indicated that some vocal training and the ability to read music were requirements; further, the chorus would devote 90 minutes each day to training at the Eastman School.

Thus, now in its third season, the Rochester American Opera Company truly seemed to be on the up and up! Watch “This Week at Eastman” for future mention of these intrepid operatic stars. There’s more to come.

►The Rochester press was glowing in its coverage of the R.A.O.C. in the first week of November, 1926.

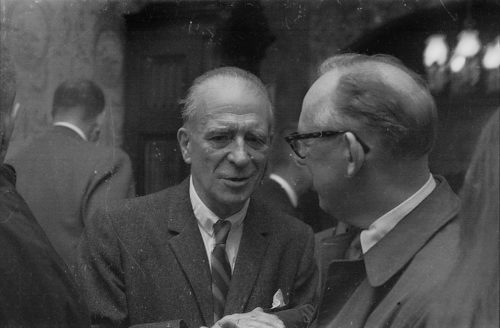

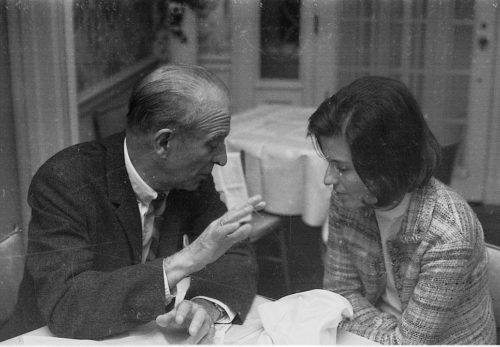

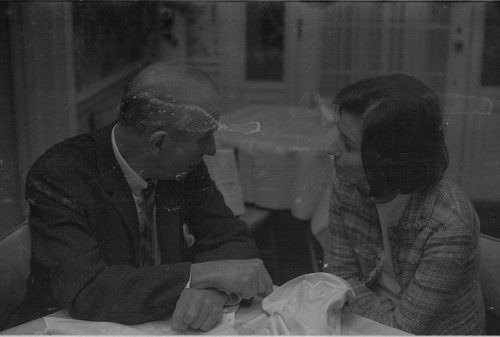

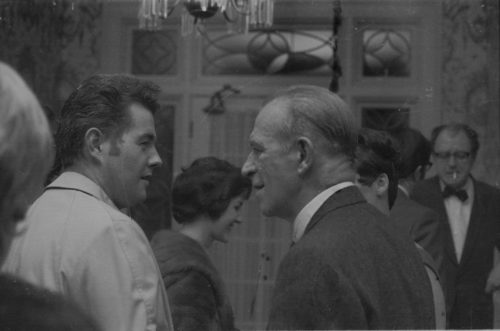

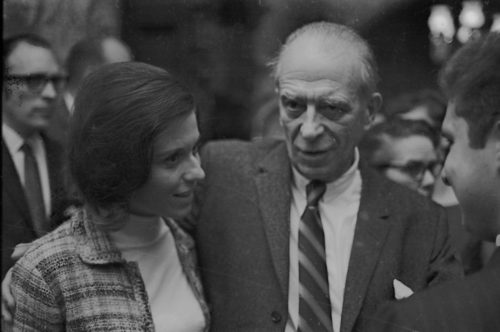

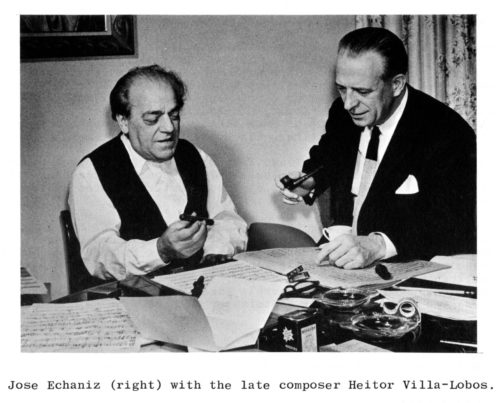

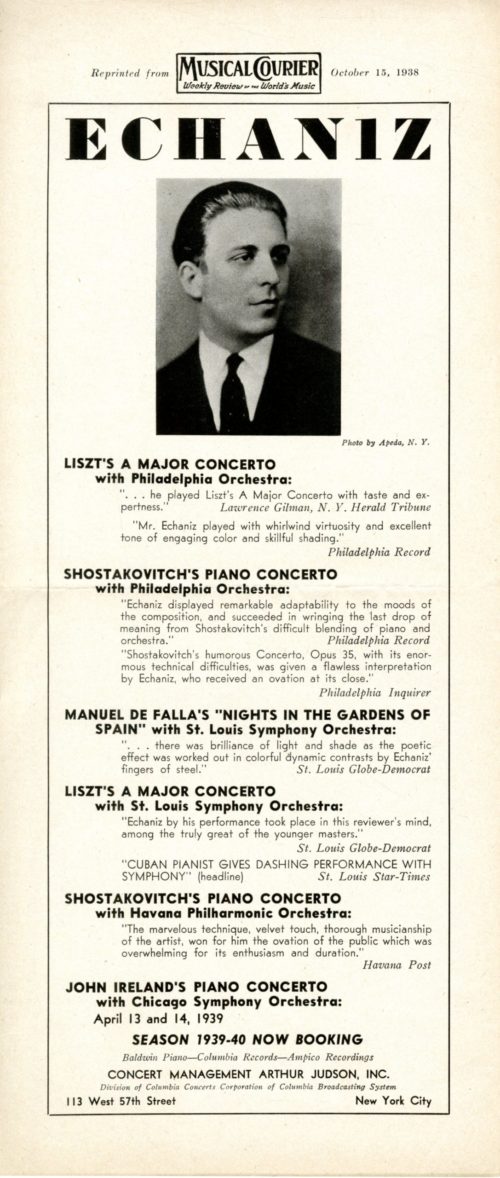

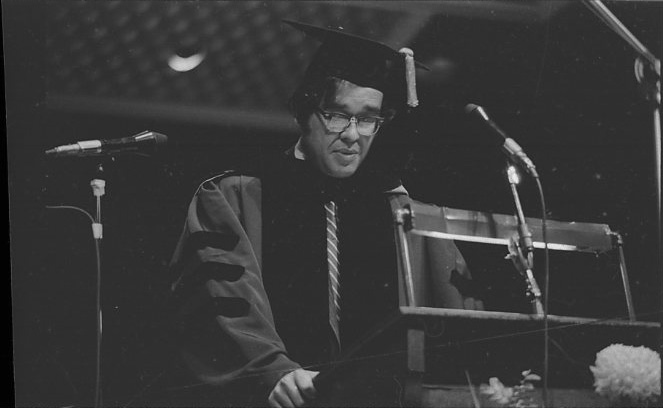

1969: 25th anniversary celebration for pianist Professor José Echániz

Previous entries of “This Week at Eastman” have recounted the Eastman tradition of gathering as a community. And so it was again, fifty-two years ago this week, on November 4th, 1969, when Eastman School Director Walter Hendl hosted a dinner for 200 guests at the Director’s official residence honoring Professor José Echániz on the milestone of his one quarter-century of service on the Eastman faculty. (Remember that the Director’s official residence was, for a certain stretch of time, Hutchison House at 930 East Avenue, right next door to George Eastman’s house.) The event was not without a certain poignancy, for November 4th was to have been the day when Mr. Echániz would give a recital in Kilbourn Hall marking his quarter-century on the Eastman faculty. At this time he was known to be ailing with cancer, and he had been forced to cancel several professional engagements. He passed away less than two months later,

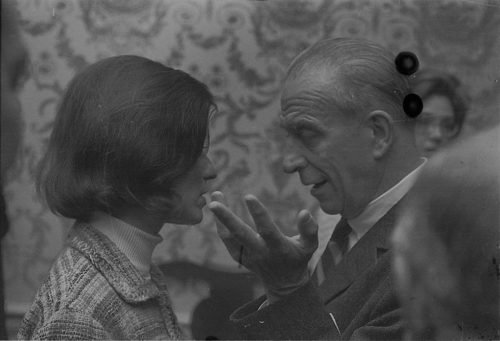

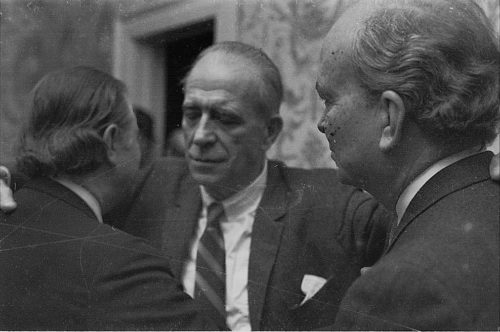

As these photographs will attest, the reception was attended by well-wishers and friends, and certainly colleagues and students, who clustered warmly around Mr. Echániz. The archival negatives are damaged and numerous images are not now retrievable; in spite of the flawed media, this photographic documentation of a special event speaks for itself.

The career of José Echániz, esteemed member of the Eastman School’s artist faculty from his appointment in 1944 until his death in 1969, was founded on three activities — teaching, performing, and conducting. Locally, he was best known for the first two, having taught an entire generation of Eastman piano students, and having endeared himself to Rochester audiences from his first performance in town, that having been a solo appearance with the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra under Dmitri Mitropoulos performing Rachmaninoff’s Concerto in C minor, December, 1944.

José Echániz surrounded by friends and well-wishes at the dinner commemorating his quarter-century on the Eastman faculty.

José Echániz in conversation with young people, these presumably his students.

Born in 1905 in Guanabacoa, Cuba, Mr. Echániz gave his first piano recital at age 14 in Havana. In 1920 he made his U.S. debut at Aeolian Hall in New York City; in 1922 he again appeared in NYC, this time at Town Hall. Between 1924 and 1927 he toured the U.S. as accompanist to Italian tenor Tito Schipa (1888-1965); their appearances included recitals in the Eastman Theater in Rochester. From 1924 until 1932 Mr. Echániz maintained a studio in Havana, and in 1932 he accepted the position of head of the piano department of Millikin University (Decatur, Illinois), a position that he held until his appointment to Eastman in 1944.

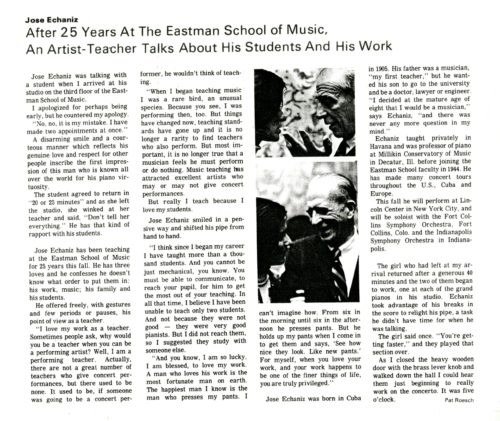

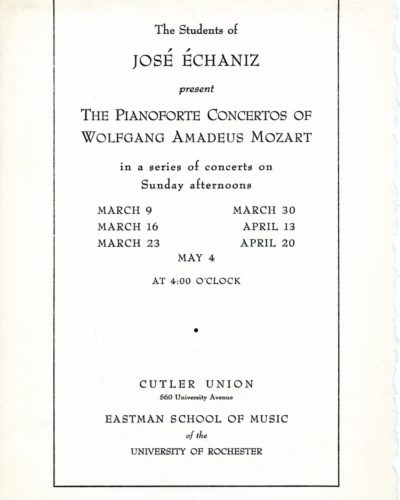

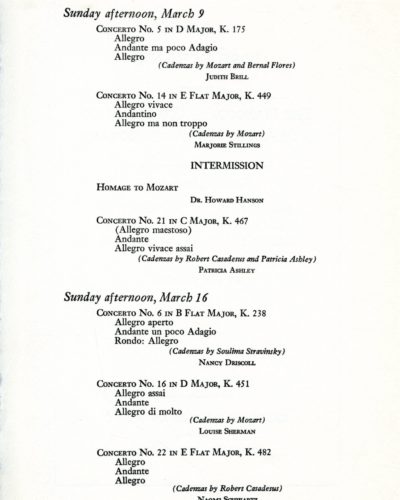

Mr. Echániz expounded on his teaching philosophy in several press interviews, including the Rochester Review article uploaded here. On several occasions he organized large-scale projects for his entire studio. Believing in the importance of a grounding in Classical-era literature, in two separate years (1958, 1963) Mr. Echániz assigned to each of his students the task of learning and performing a piano concerto by Mozart, a composer with whom he himself bore a strong affinity. In the public performances that ensued, Mr. Echániz himself accompanied his students on second piano. In 1961 the Echániz studio presented a Bach Festival, featuring the Goldberg Variations and Book II of the Well-Tempered Clavier. In 1967 his students mounted a second Bach Festival, this one featuring the Well-Tempered Clavier in its entirety.

This 1958 recital series was one of two occasions when the entire Echániz studio learned and performed the complete piano concertos of Mozart.

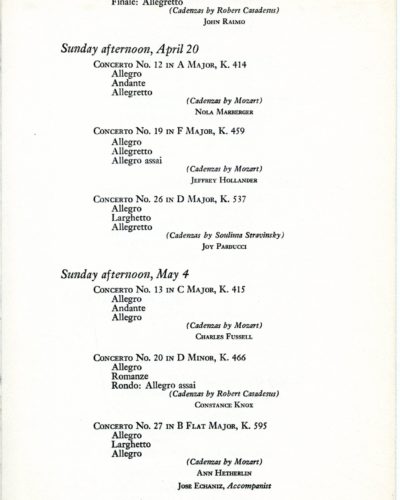

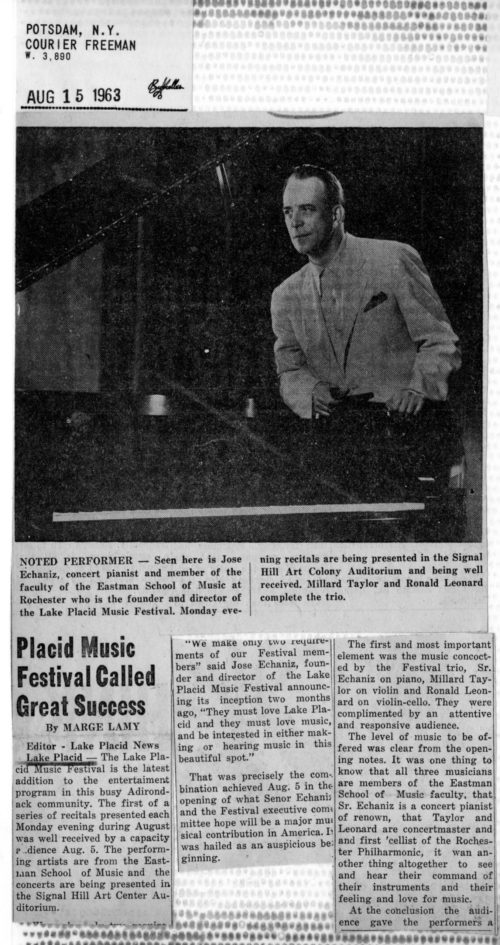

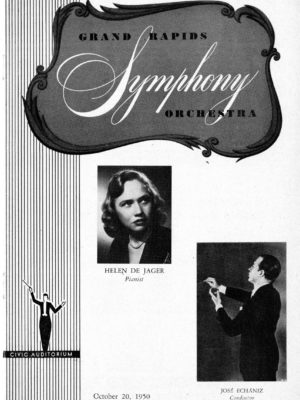

Mr. Echániz described himself as “a performing teacher” in an interview in 1969. While that description would not seem extraordinary today, the fact is that few Eastman performance faculty members in the 1940s or 1950s were performing so frequently, or over so broad a geographic span, as he was. While devoting the greater part of his professional time to teaching, he nevertheless maintained an active performing schedule as either pianist or conductor. In the latter capacity, Mr. Echániz served as music director of the Grand Rapids Symphony Orchestra for six seasons (1948-54). As pianist, during his Eastman years he undertook three European tours, in addition to several U.S. tours and appearances in Cuba. Ever a favorite with Rochester audiences, Mr. Echániz gave a Kilbourn Hall recital every other year, made five solo appearances with the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra, and also performed with the Eastman Chamber Orchestra and with numerous of his Eastman colleagues, including violist Francis Tursi and violinist John Celentano. Outside of Rochester, he founded an annual chamber music festival at Lake Placid, and in that connection he performed as pianist in the festival’s signature ensemble, the Lake Placid Festival Trio.

Mr. Echániz’ native flair for the music of Spanish and Latin American composers was much in evidence in both his recitals and his recording projects. In all, he made more than one dozen recordings, most of which were released on the Westminster label in the dozen or so years between the late 1950s and 1970. The works of Federico Mompou, Isaac Albéniz, and Manuel de Falla were staples in his performing repertoire, but Falla’s music held a special significance for him, for Mr. Echániz met Falla in 1929 during a tour of Spain, and was honored to receive the composer’s annotations in his scores. Strangely, in spite of having recorded Falla’s complete solo piano music, Mr. Echániz made no recording of that composer’s Noches en los járdines de España (Nights in the Gardens of Spain) for piano with orchestra, a work that he had performed in concert many times, including a 1956 solo appearance with the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra. His last recording was an album of Franz Liszt issued posthumously in 1970 on the Westminster label. Significantly, Mr. Echániz had recorded the album entirely in one “take” — a rare occurrence in the recording studio, then or now.

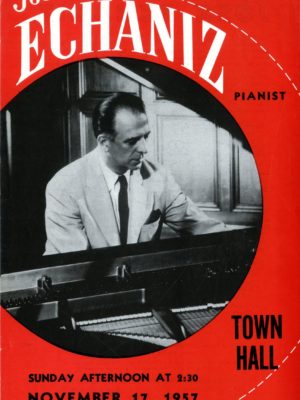

Demonstrating his interest in contemporary music, Mr. Echániz cared to perform his colleagues’ works. An admirer of Howard Hanson’s efforts to promote American music and American composers, Mr. Echániz gave the Rochester premiere of Howard Hanson’s Piano Concerto in G major, a performance given at the Eastman School’s 1949 Festival of American Music. In 1948 he gave the premiere performance of the Sonata for Piano (1948) by Professor Wayne Barlow (1912-1996) in a Town Hall recital (New York City), and repeated the performance in Rochester a short time later. He also performed locally Professor Barlow’s Quintet for Piano and Strings with the members of the Gordon String Quartet. Two decades later, Mr. Echániz was scheduled to give the premiere performance of David Diamond’s Concertino for Piano and String Orchestra, which he had commissioned and of which he was the dedicatee, but his ill health at that time prevented the performance from taking place.

Mr. Echániz’ later years were marked by a renewed interest in performing. The New York Times noted posthumously that his performances had taken on an intellectual quality in his mature years (as stated in the obituary, “Jose Echániz, 64, concert pianist” printed on December 31st, 1969). “My life has been all wrong,” Echániz smilingly told a reporter on the eve of a return engagement at Philharmonic Hall (New York City) in December, 1968. “When I was young, you were supposed to wait before you played in public. Now that I am ‘over 50,’ the trend is all toward youth. I think I was one of the first concert artists to go into teaching who did not try to hide it, but now I’d like to play a bit more and teach less. I feel like I’m starting out on a new career, and that is why I’m giving two recitals (in New York City in December, 1968 and February, 1969). It makes it a little more spectacular.” (Cited in “Not an opera, but close to it” by Raymond Carver, The New York Times, December 1st, 1968.) However, ill health inevitably curtailed his performing. An onset of the flu forced Mr. Echániz to cut short the December, 1968 recital at the intermission, and the planned February, 1969 performance did not take place. The 1969-70 season was to have been his busiest performing season in years, but in the fall of 1969, cancer prevented him from fulfilling many scheduled engagements, including a Kilbourn Hall recital that was to have marked the 25th anniversary of his Eastman School appointment. He died at home on December 30th, 1969. Flags at the University of Rochester were flown at half-mast on the day of his funeral Mass, which was celebrated at the Church of the Blessed Sacrament in Rochester. Faculty members John Celentano and Alan Harris were among those who performed at the funeral, which was attended by Director Walter Hendl and former Director Howard Hanson and many other members of the Eastman School community.

Mr. Echániz was eulogized in the February, 1970 issue of Notes from Eastman, the cover of which bore his photograph. (Notes from Eastman was the forerunner to today’s Eastman Notes, albeit in black and white and in a smaller format.) In addition, The Score 1970 carried a two-page pictorial tribute to Mr. Echániz. His portrait hangs on Cominsky Promenade. Since 1972, an Echániz Memorial Fund has provided assistance to Eastman piano students.

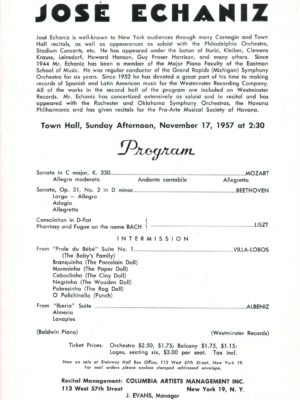

► Publicity items promoting Mr. Echániz as both pianist and conductor. José Echániz Collection.

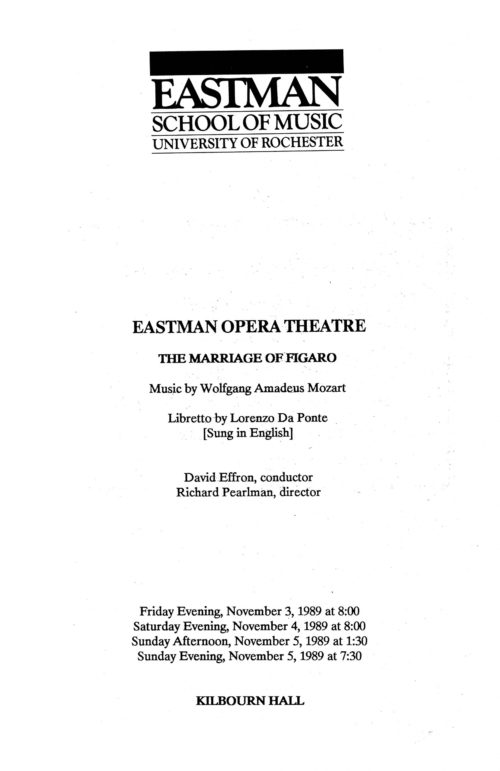

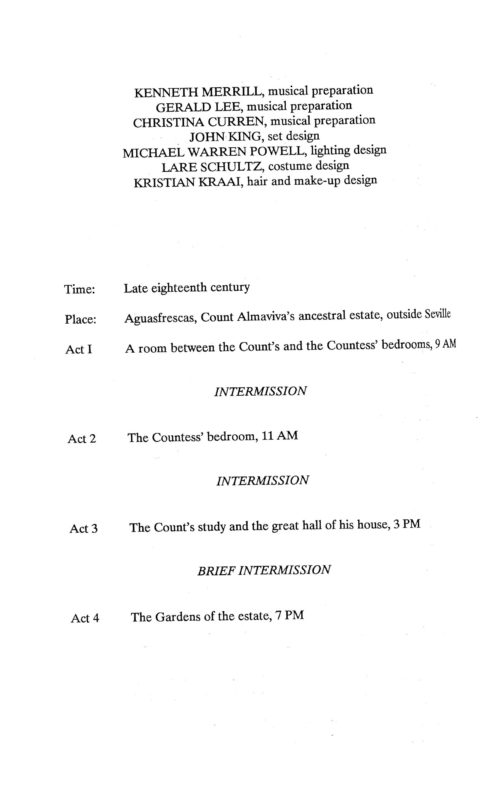

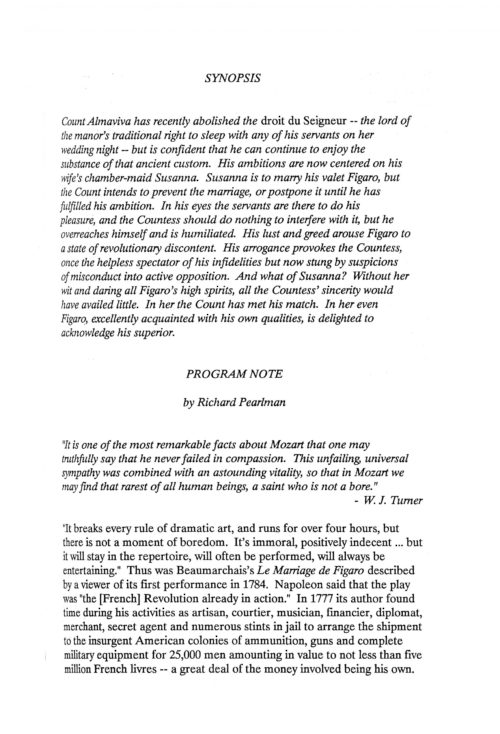

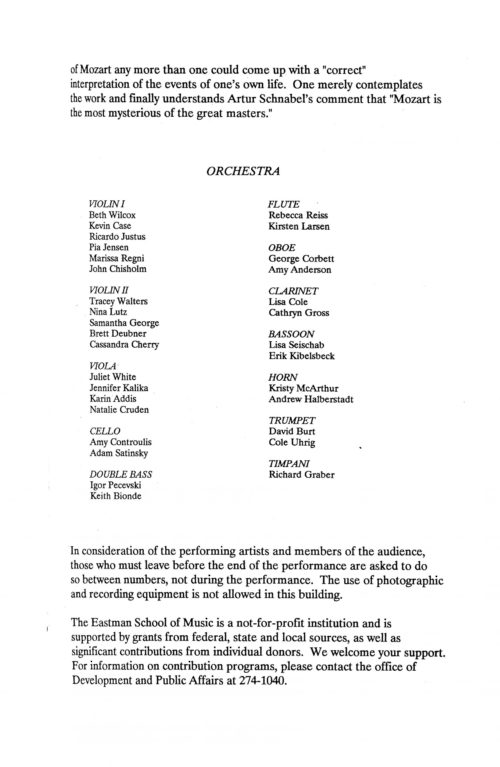

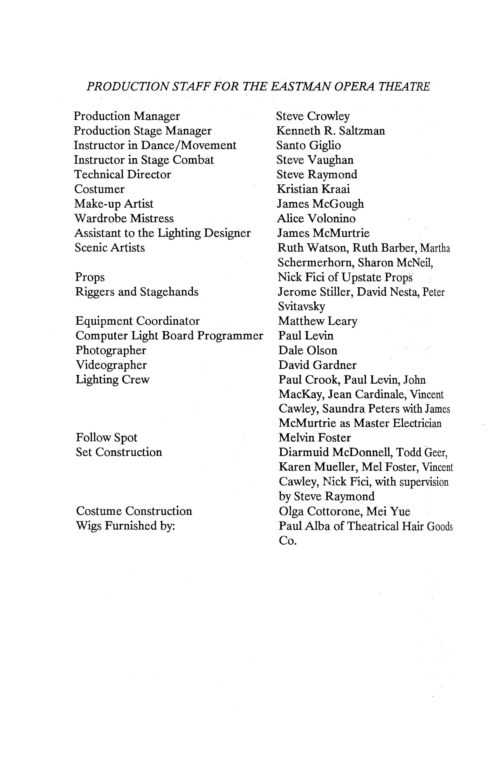

1989: EOT presents The Marriage of Figaro

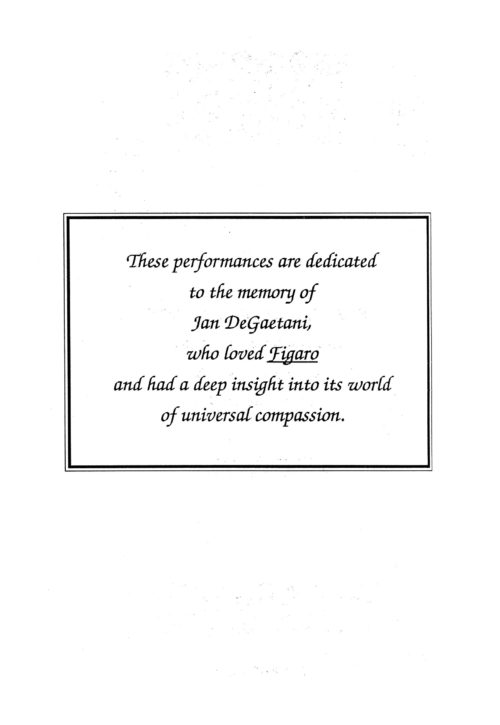

Thirty-two years ago this week, on November 3rd, 4th, and 5th, 1989, Eastman Opera Theater presented W. A. Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro in a production directed by Richard Pearlman. Significantly, the November, 1989 performances were dedicated to the memory of the then-recently deceased Jan DeGaetani (1931-1989), esteemed mezzo-soprano and beloved Eastman faculty member (served 1973-1989), “who loved Figaro and who had a deep insight into its world of universal compassion” as the printed program paid tribute to her.

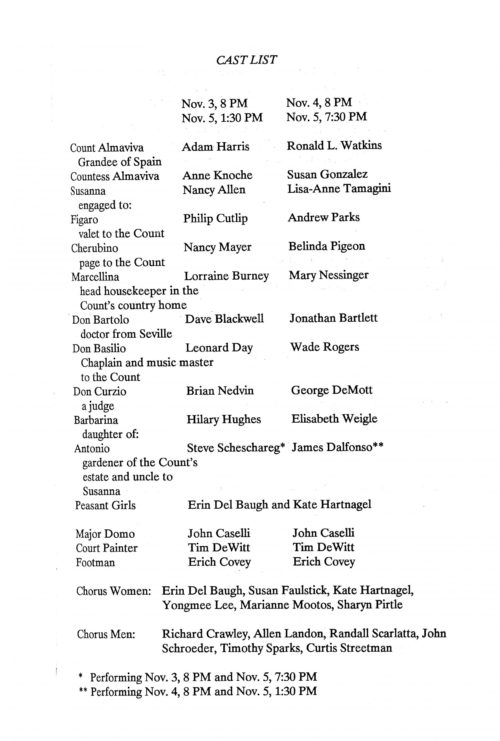

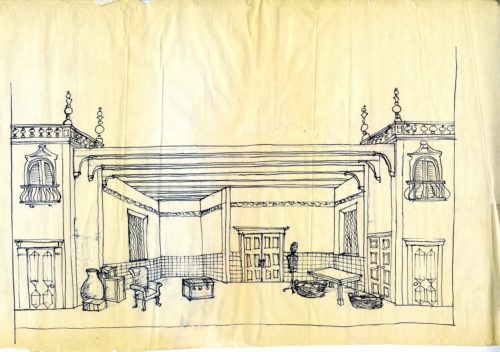

A perennial audience favorite and frequently performed wherever opera is produced, The Marriage of Figaro has been staged at Eastman eleven times in its entirety (between 1948 and 2016). Four of those productions were directed by Mr. Pearlman (1979, 1984, 1989, 1993). In the 1989 production Mr. Pearlman sought, as he stated in his Director’s notes in the program, “to scrape away as many ‘traditional’ barnacles as possible and to let the work speak for itself.” Mr. Pearlman elaborated in his notes about the various trappings of tradition that scholarship and inquiry had succeeded in exposing in this opera. The audience was not given much more than that to go on, for the printed program did not happen to provide a detailed synopsis nor a listing of musical numbers, nor was information provided about the specific edition or editions that had informed the production. Nevertheless, the production was captured in an aural format, as the Eastman Audio Archive holds the master tapes of this production as sung by both casts.

Whether at Eastman or elsewhere, Mr. Pearlman had acquired a healthy reputation as a director who was less than fearful about pushing boundaries. Examples of same at Eastman included the spring, 1978 staging of Rossini’s The Barber of Seville set in pre-Castro Havana (and ending with the Castro revolution); the fall, 1988 staging of Benjamin Britten’s Albert Herring which commented slyly (if not, in fact, acidly) on Margaret Thatcher’s presumed capitalist Utopia in 1980s Britain; and the spring, 1989 staging of Monteverdi’s The Coronation of Poppea set in Mussolini’s Fascist Italy. Notwithstanding the risk-taking interpretations that his years of research and his own artistic predilections had informed, Mr. Pearlman resolutely insisted that a director’s primary obligation was to serve the music. He was quoted as having told The Chicago Tribune, “If you try to go against that, it never comes out right.” (The quotation was published in his obituary in The New York Times on April 13th, 2006, and was replicated in numerous other publications and on several websites.) As suggested in these photographs by Louis Ouzer, the production values of Figaro in the fall of 1989 adhered strictly to the 18th century.

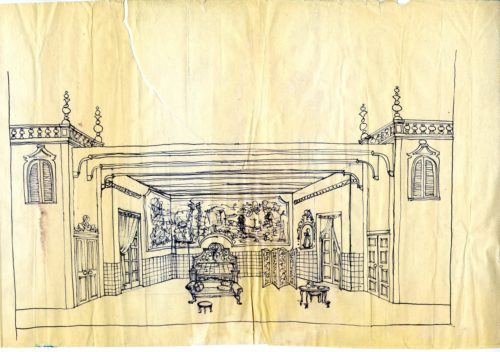

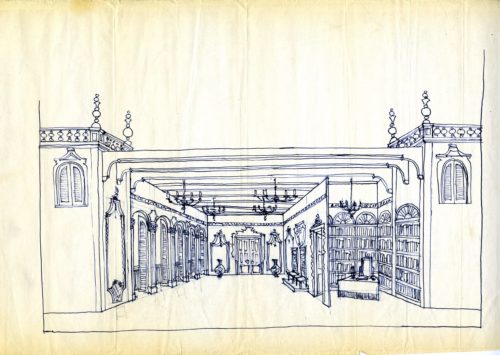

►Stage set renderings for the EOT production. Richard Pearlman Collection.

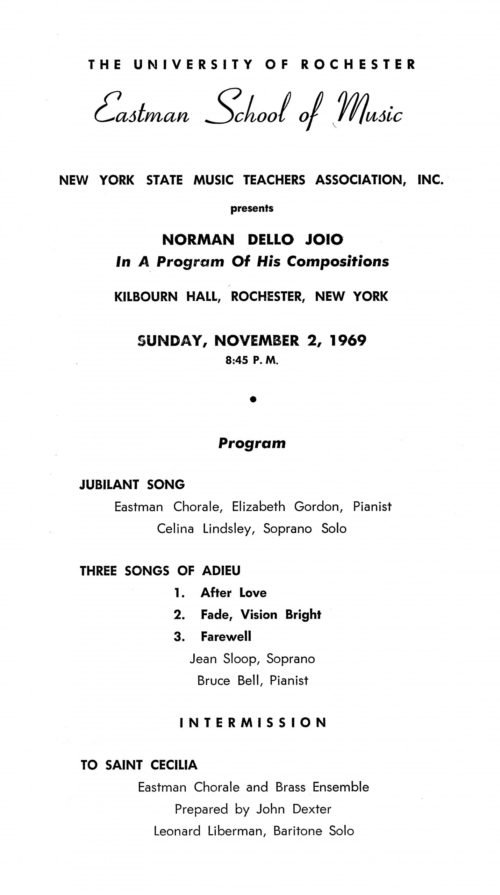

► Photos of the Figaro cast members shot on November 2nd, 1989.

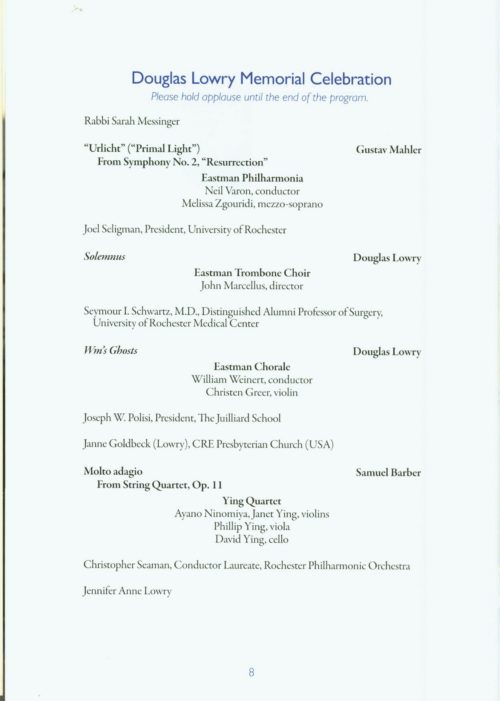

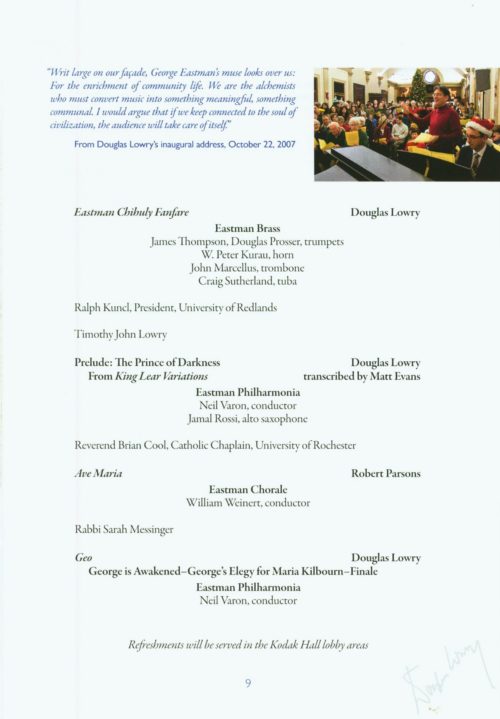

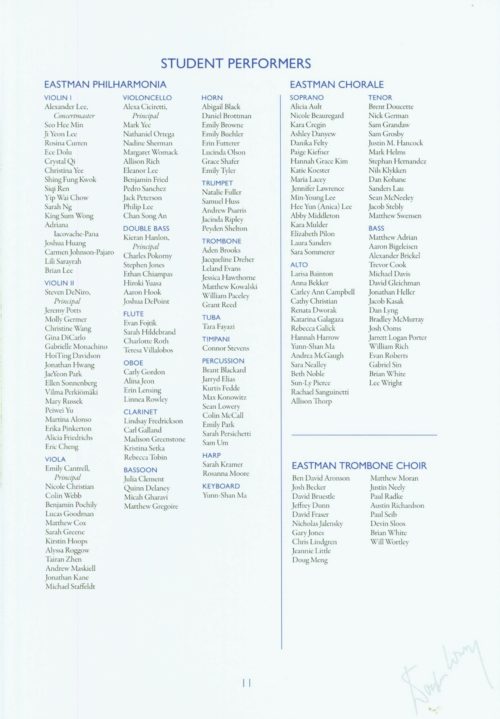

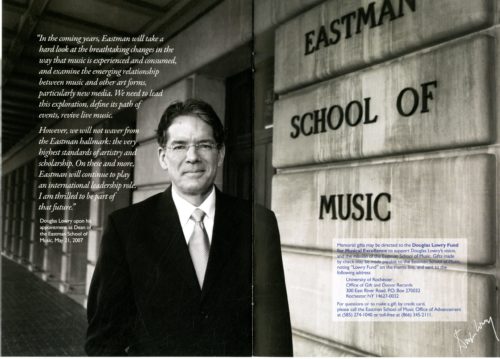

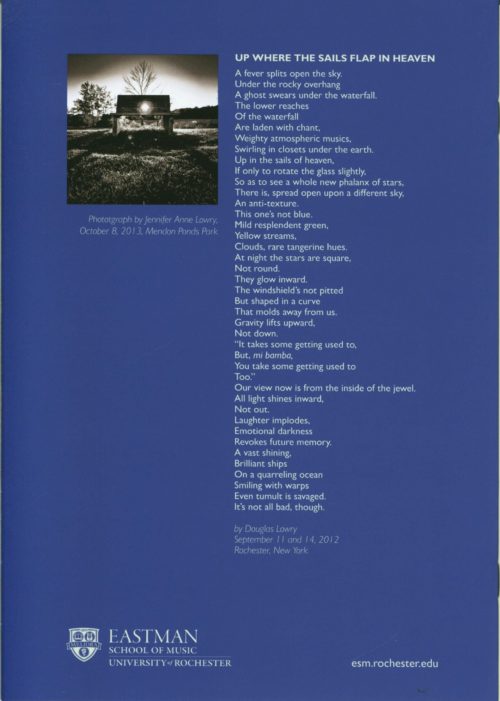

2013: Douglas Lowry Memorial Celebration

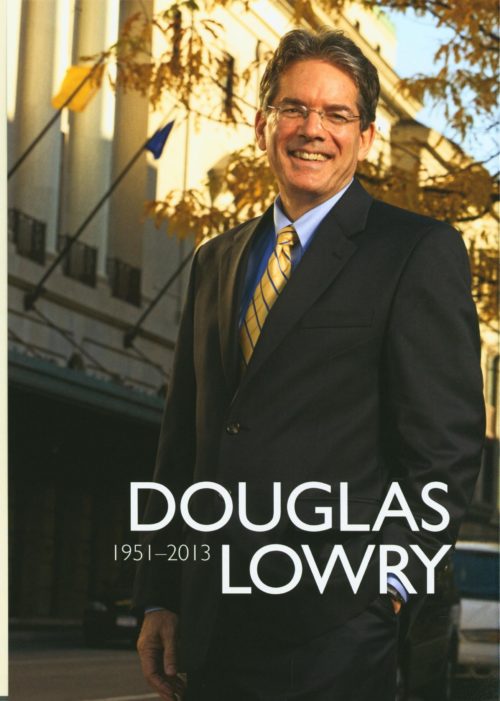

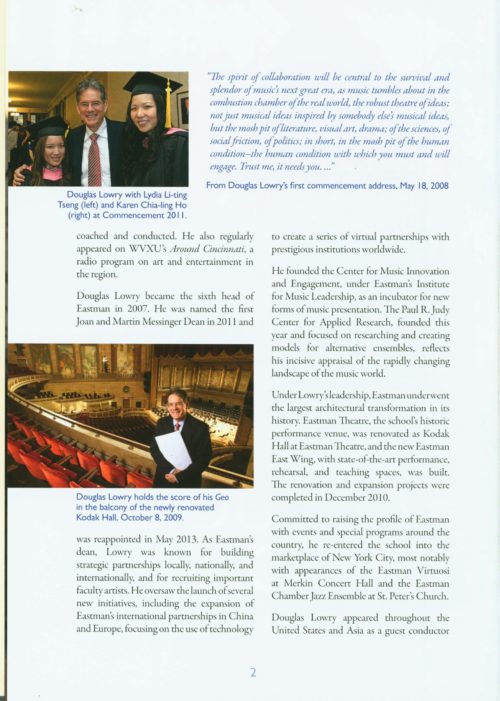

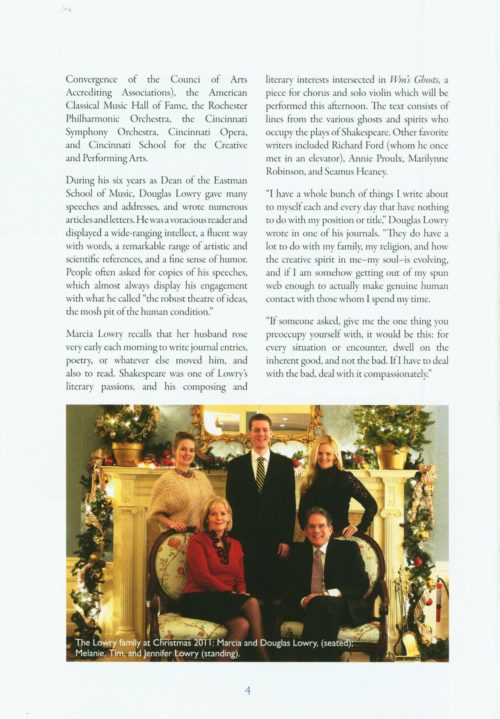

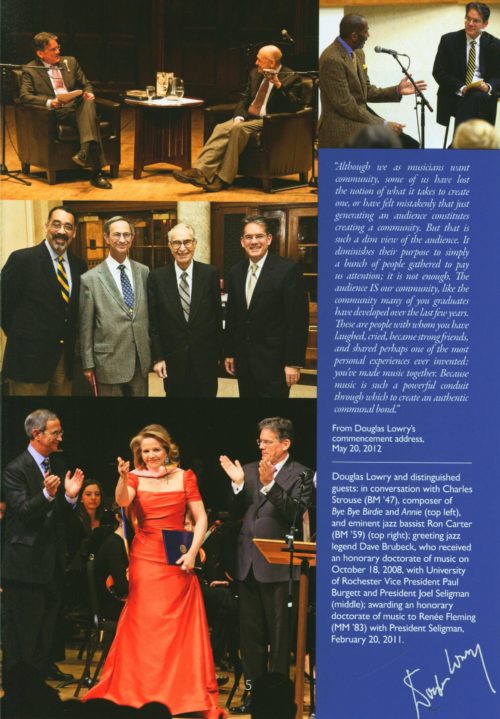

Eight years ago this week, on Sunday, November 3rd, 2013, the extended Eastman community—joined by many, many others—gathered in Kodak Hall at Eastman Theater to celebrate the life of Douglas Lowry (1951-2013), Dean of the Eastman School of Music from 2007 until his untimely death in 2013. His loss was keenly felt and he left many, many friends throughout the world. His portrait hangs in Lowry Hall, and the Eastman School website carries a tribute to his many contributions to Eastman life.

The commemorative booklet that the Eastman School published for the memorial celebration spoke eloquently to so much of what was meaningful, essential, and memorable in Mr. Lowry’s eventful life and illustrious career.

What memories do you have of Dean Lowry (whether at Eastman or elsewhere)? Contact us and share them!

The Weekly Dozen

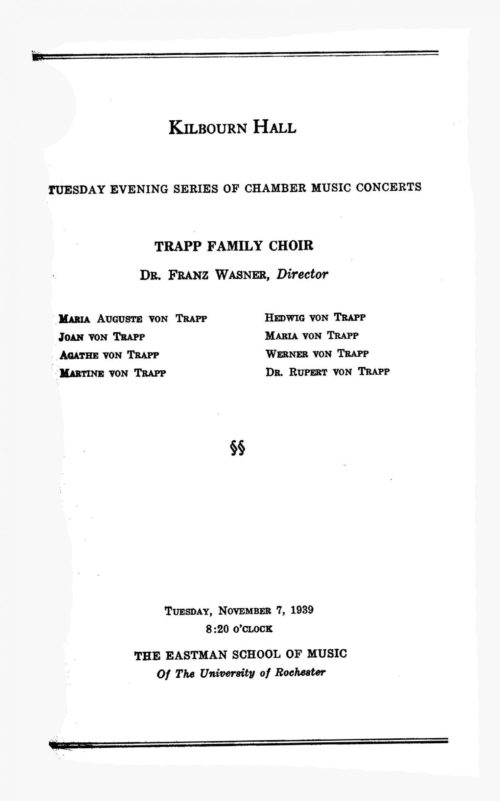

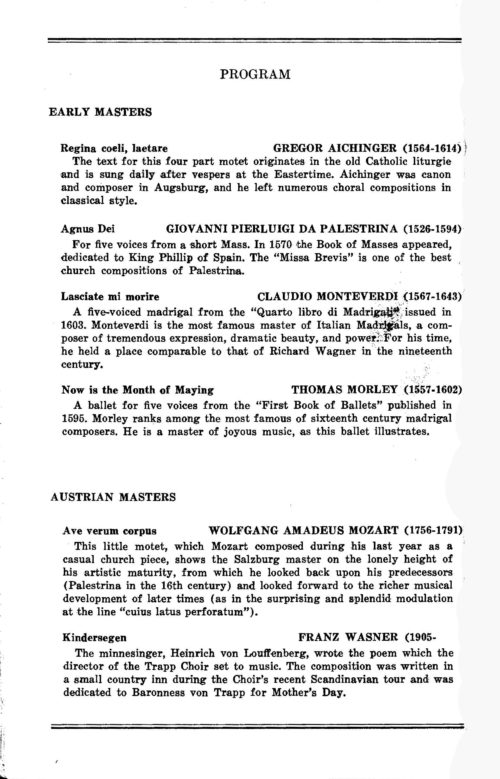

►November 7, 1939 The von Trapp Family Choir

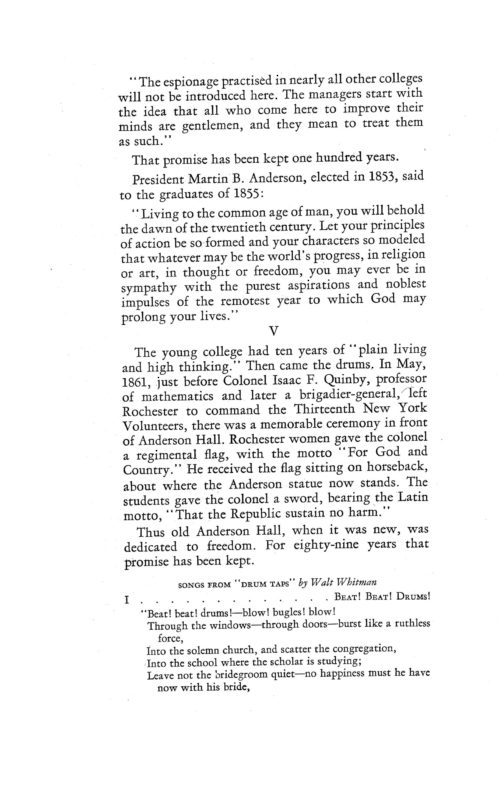

►November 6 1950 UR Centennial Ode

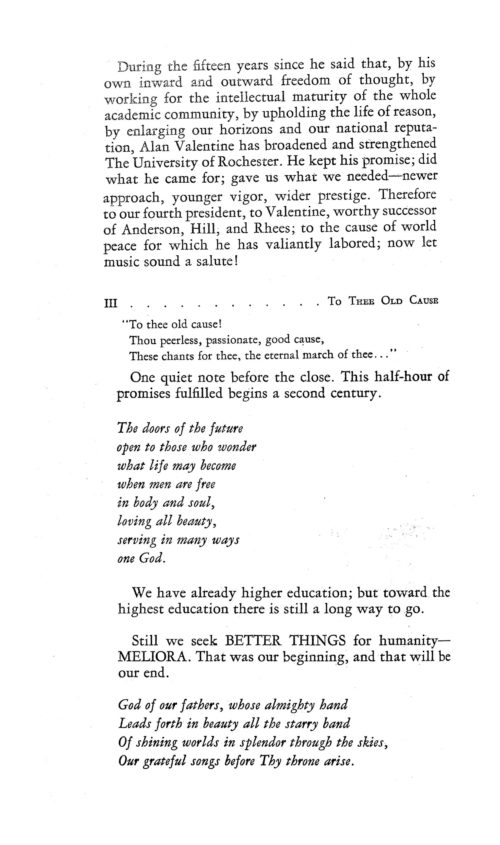

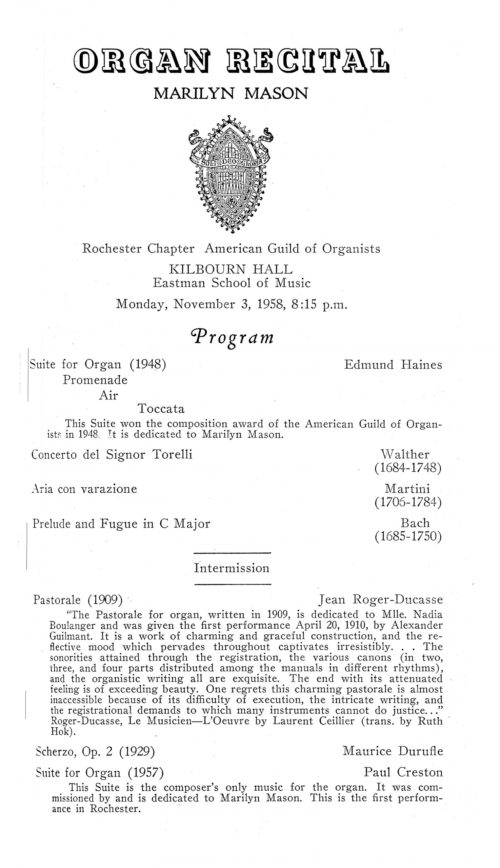

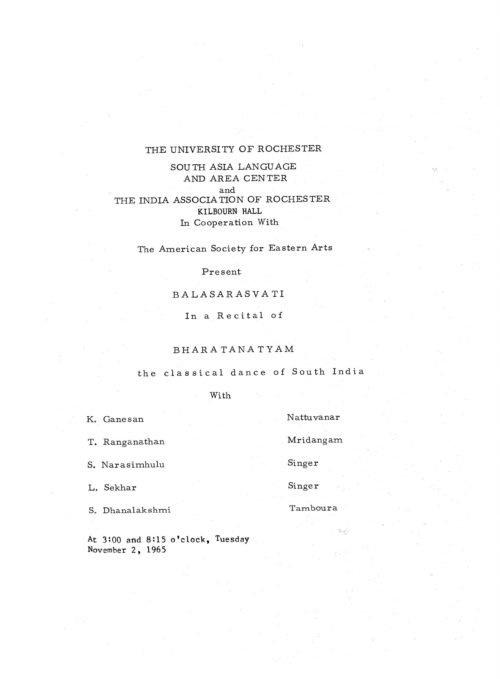

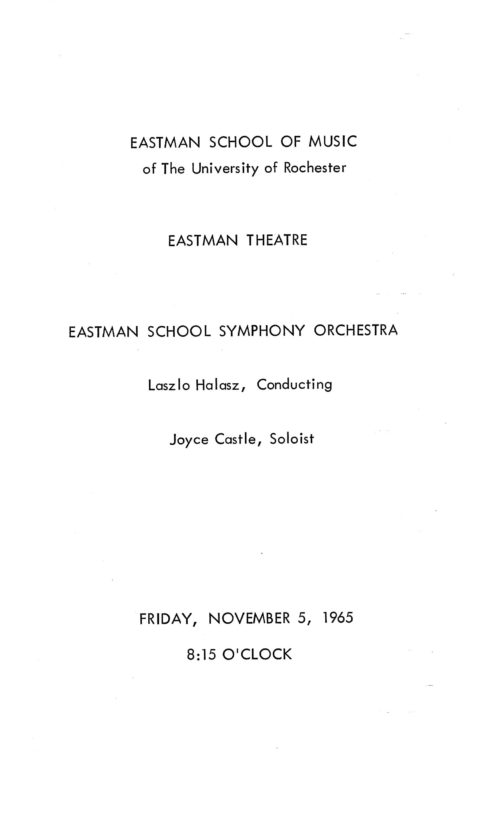

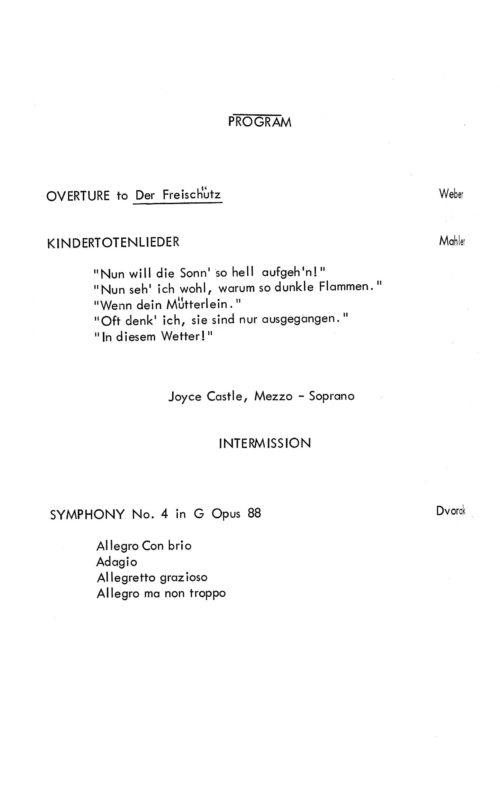

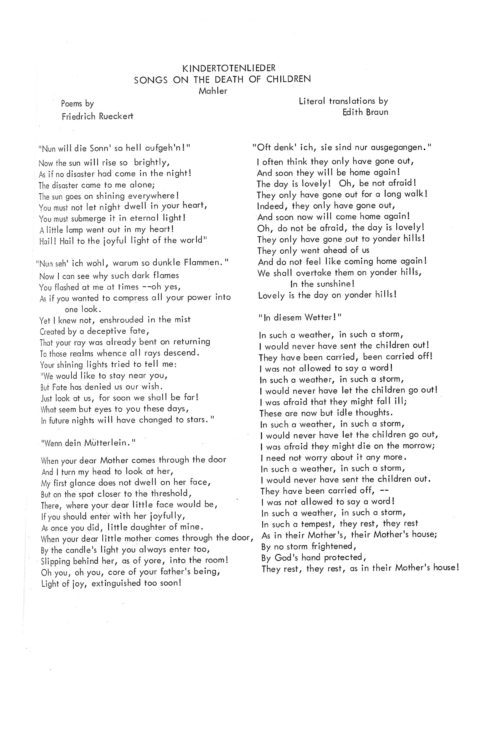

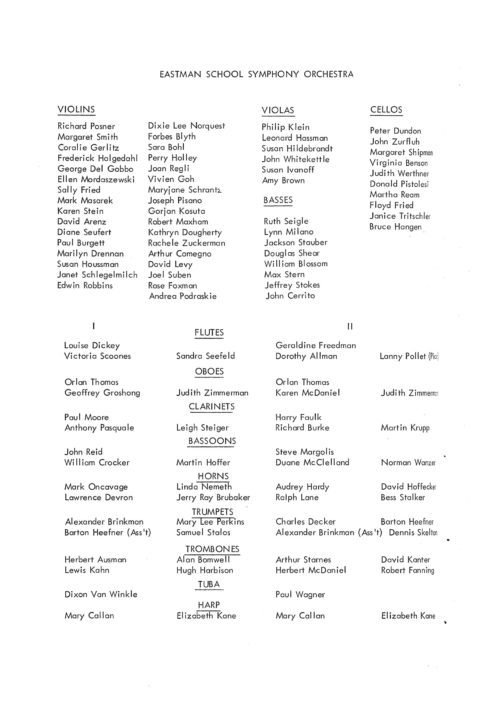

►November 2, 1965 Balasaraswati Classical South Indian Dance

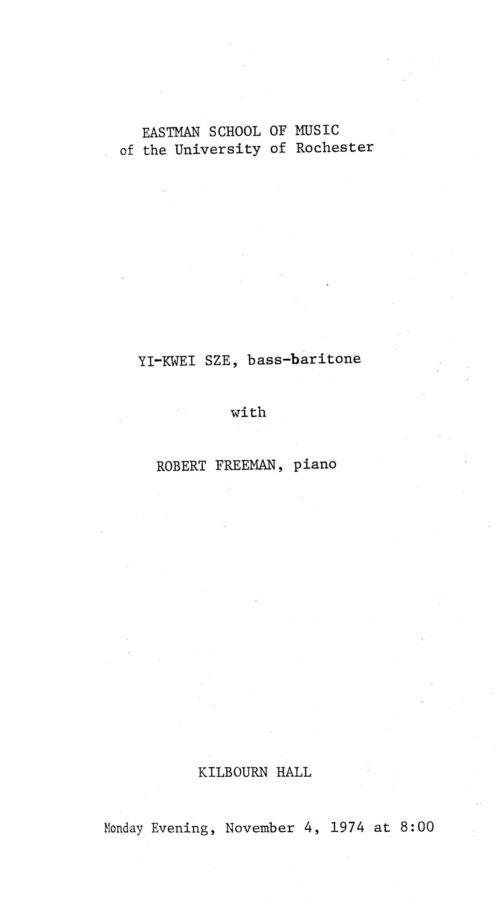

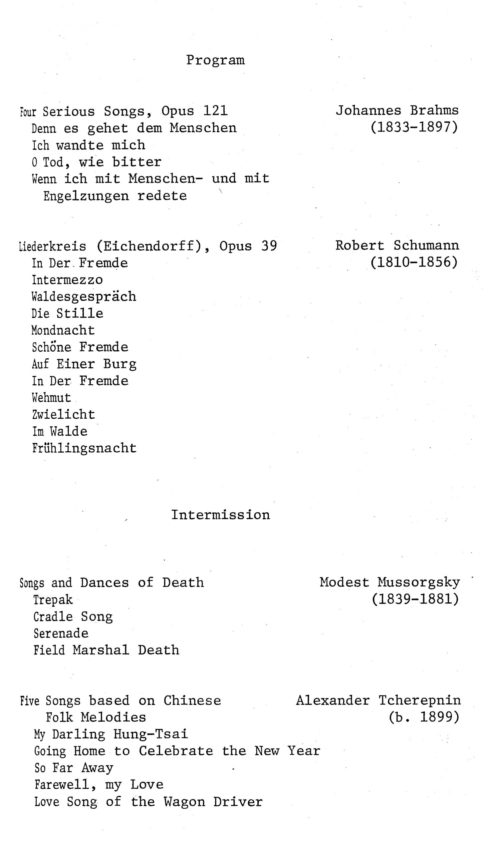

►November 4, 1974 Yi-Kwei Sze (bass-baritone) and Robert Freeman (piano)

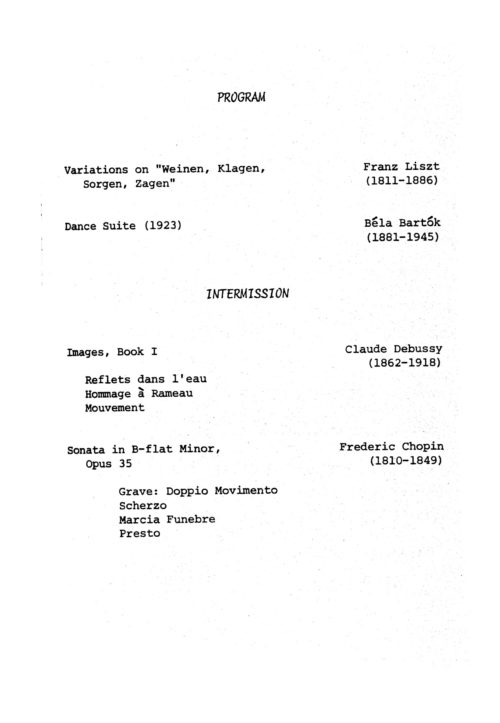

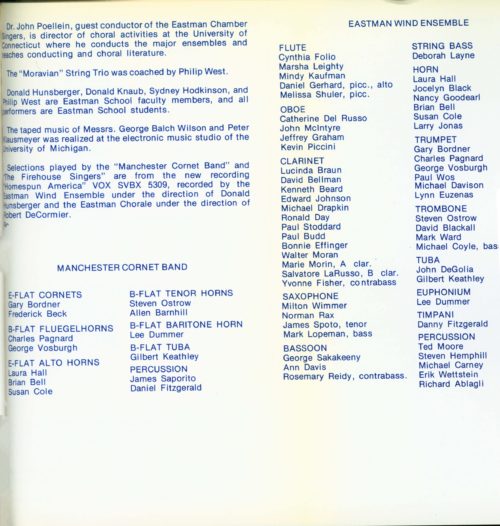

►November 3, 1976 Robert Silverman, Pianist

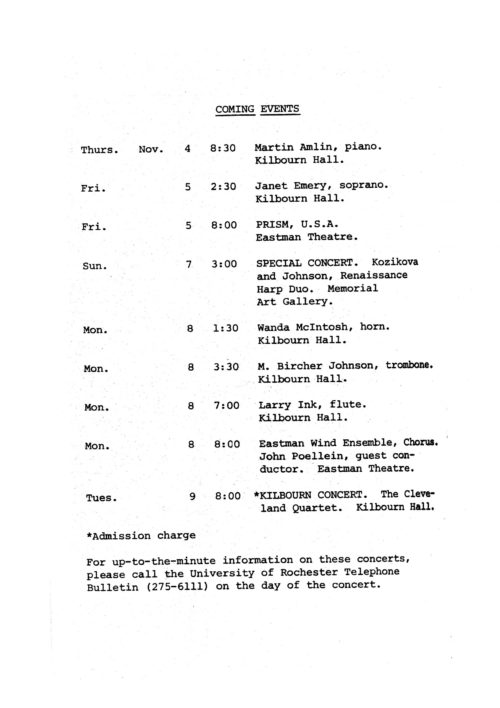

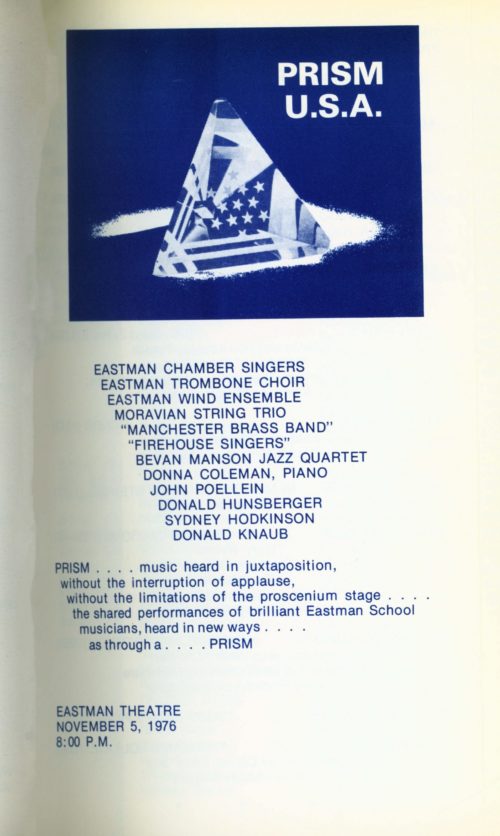

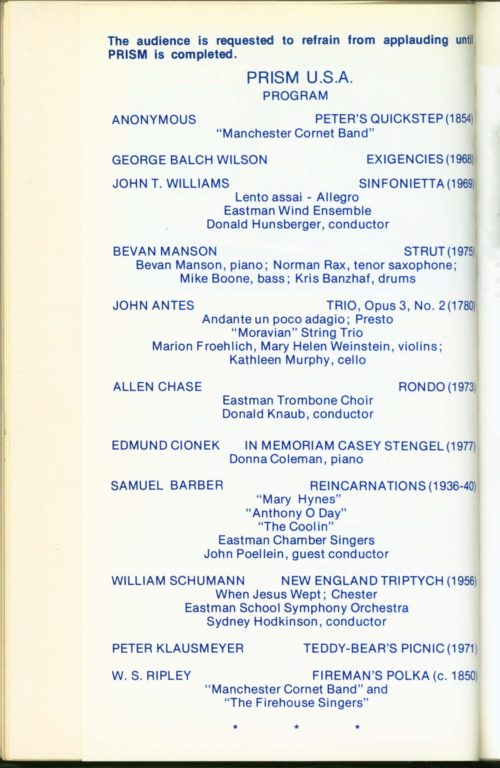

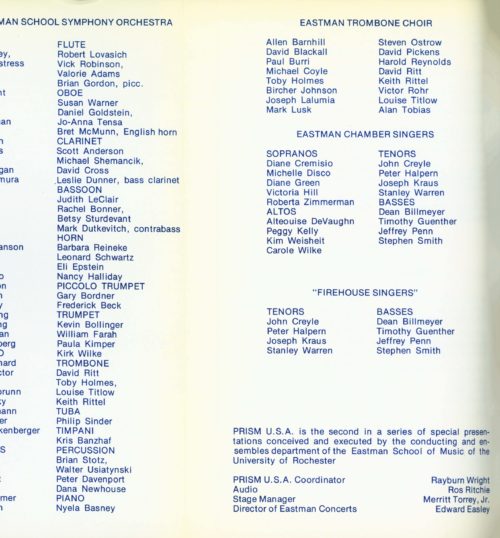

►November 5, 1976 PRISM Concert

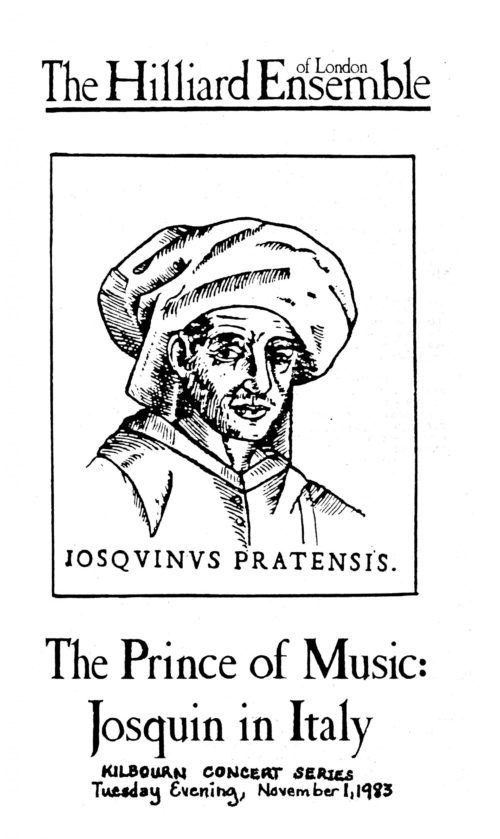

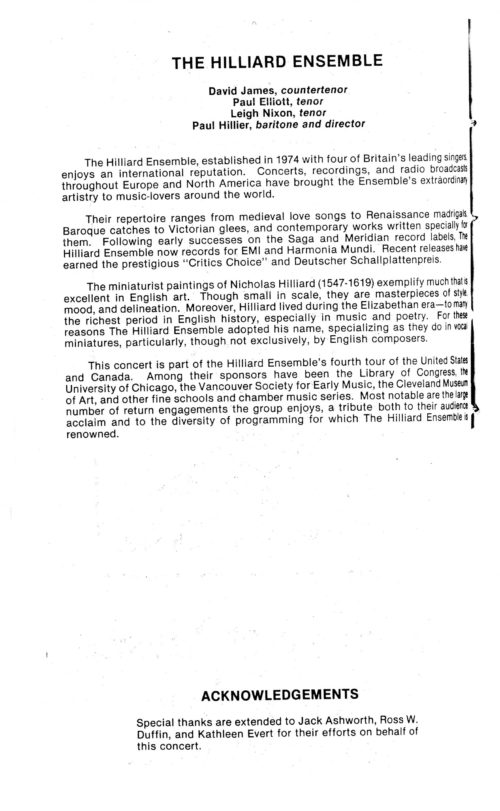

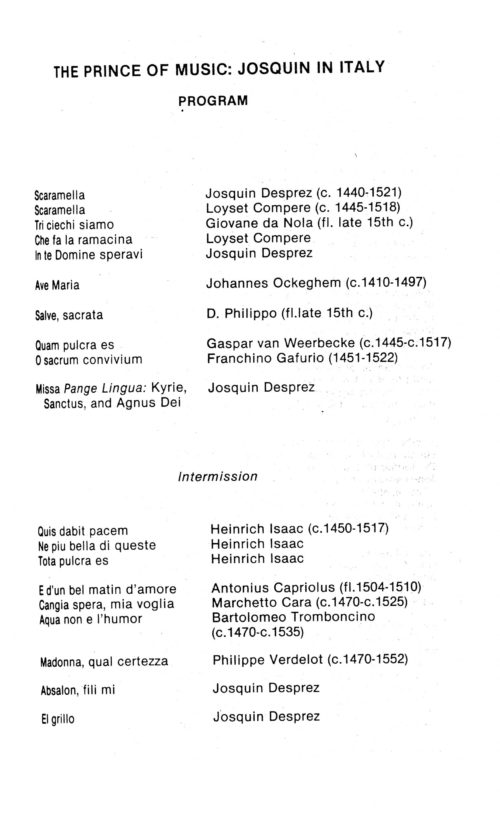

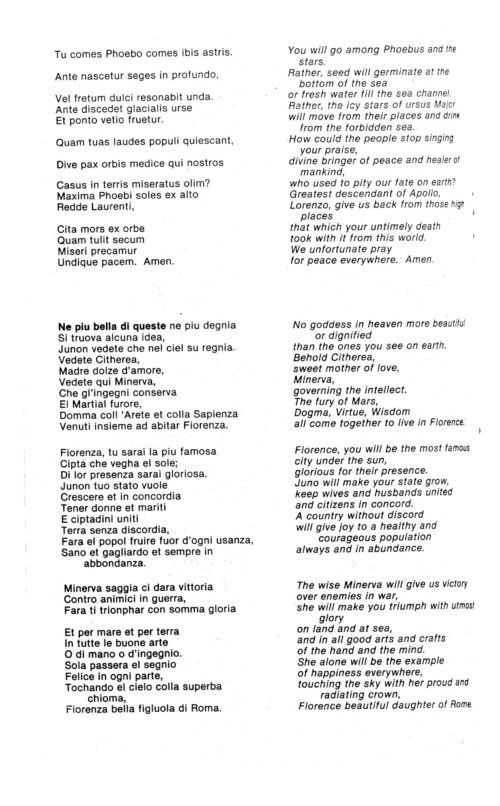

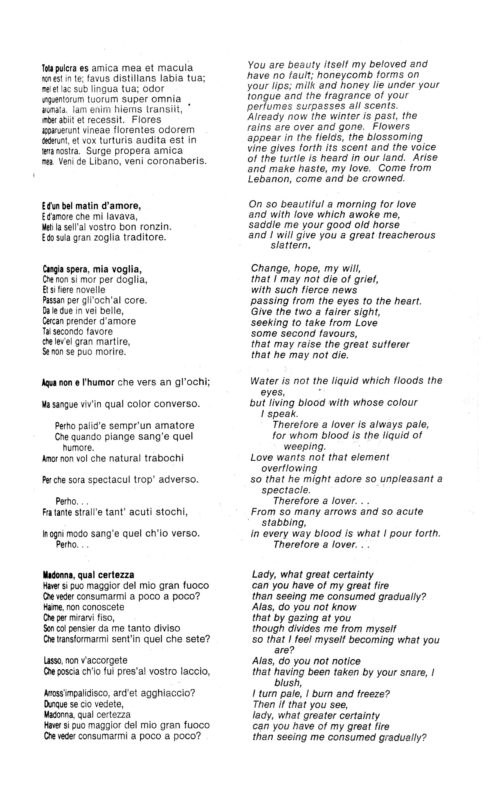

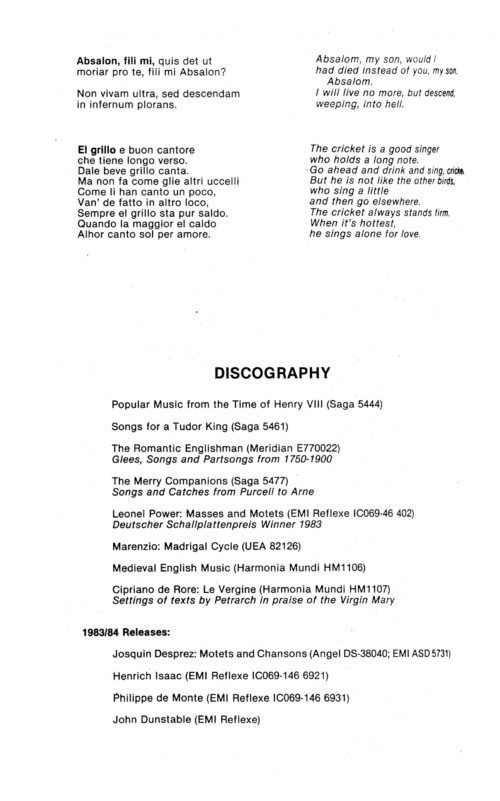

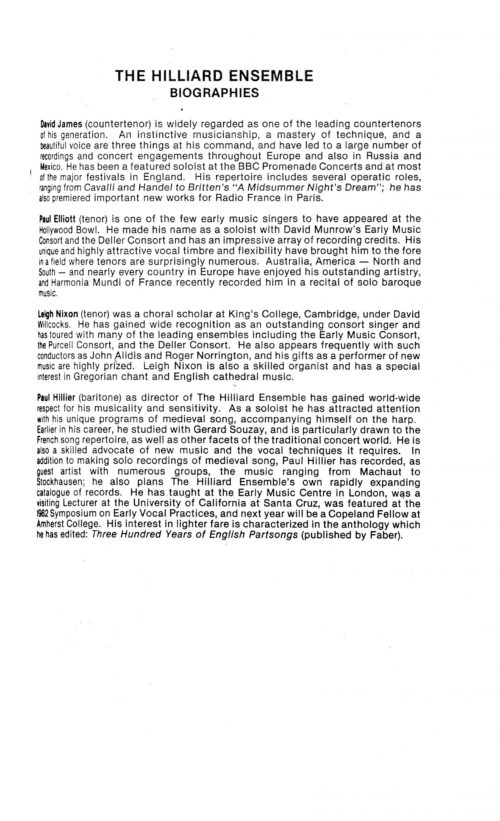

►November 1, 1983 Hilliard Ensemble of London

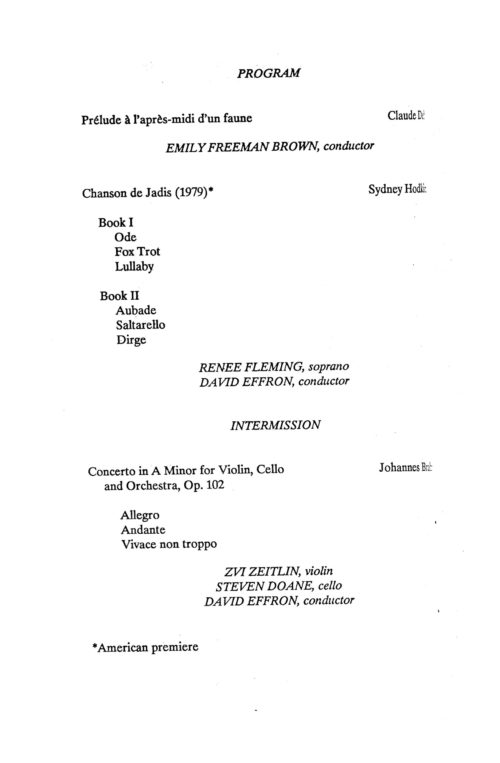

►November 6, 1987 Eastman Philharmonia with Renee Fleming

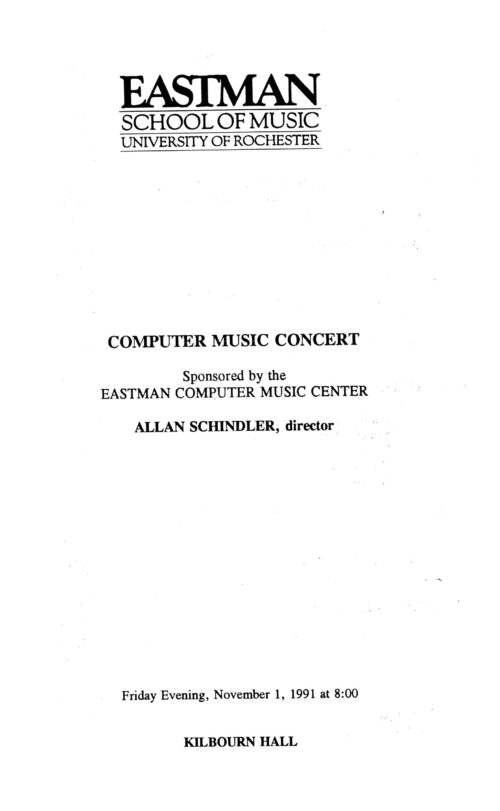

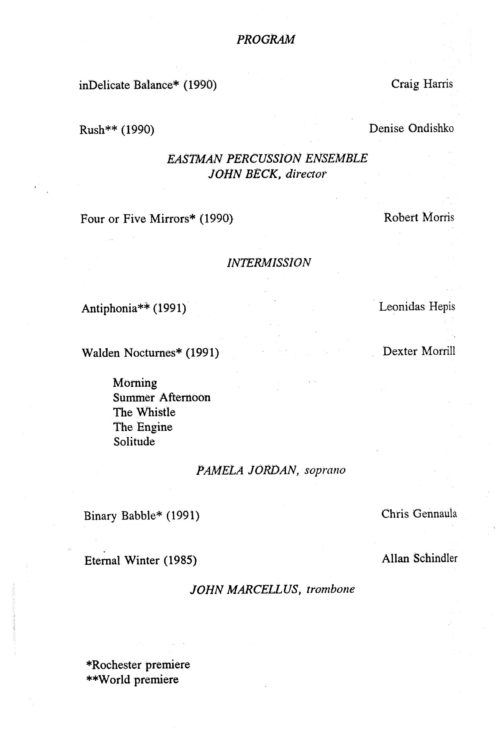

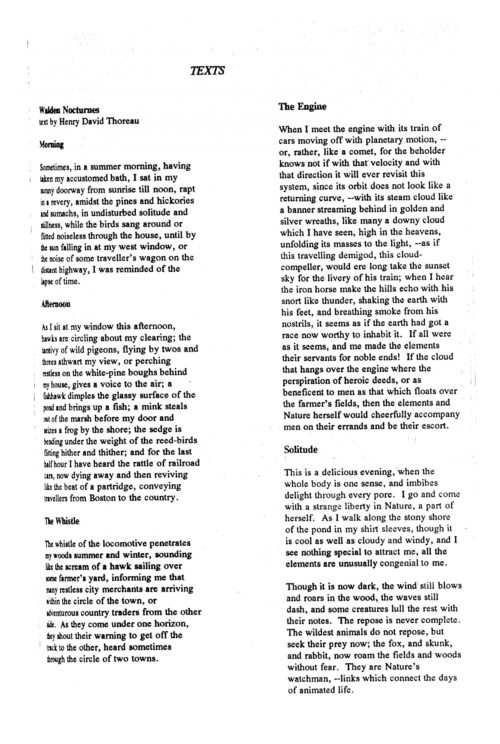

►November 1, 1991 Computer Music Concert