Drew Nobile

Abstract

This article argues that the Beatles took a particular approach to narrative structure in their verse–chorus songs. That approach is narrative opposition, where the two sections present contrasting ideas or settings. The song’s meaning thus arises through synthesizing the two ideas. This approach differs from the mainstream standard that emerged in the late 1960s, wherein the chorus is the song’s primary narrative focus, with verses playing a supporting role. To demonstrate, I analyze four songs from the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper sessions—the peak of what John Covach calls their “artist” period (Covach 2006). Through these analyses, I show how the Beatles used verse–chorus form as a specific expressive device rather than a neutral template as did later artists.

View PDF

Return to Volume 36

Keywords and phrases: the Beatles, form, lyrics, narrative analysis, popular music

Introduction

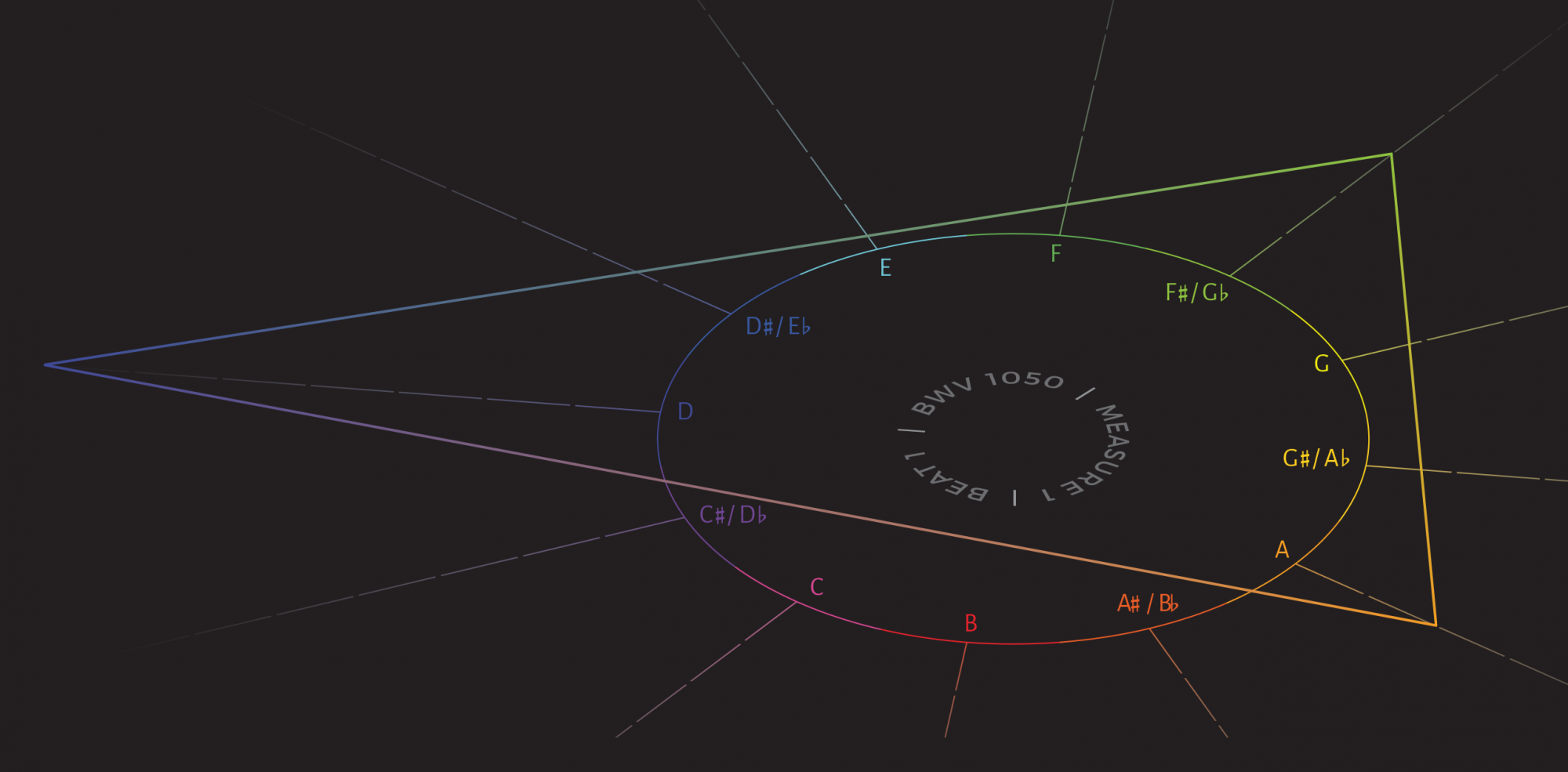

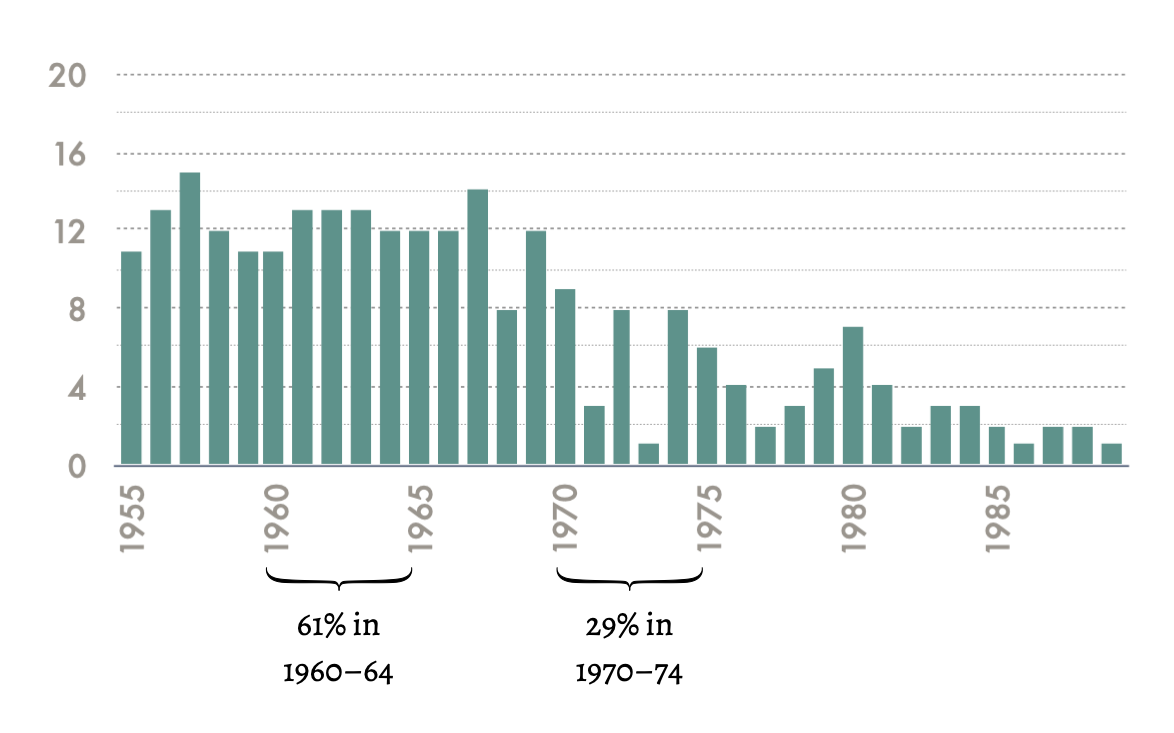

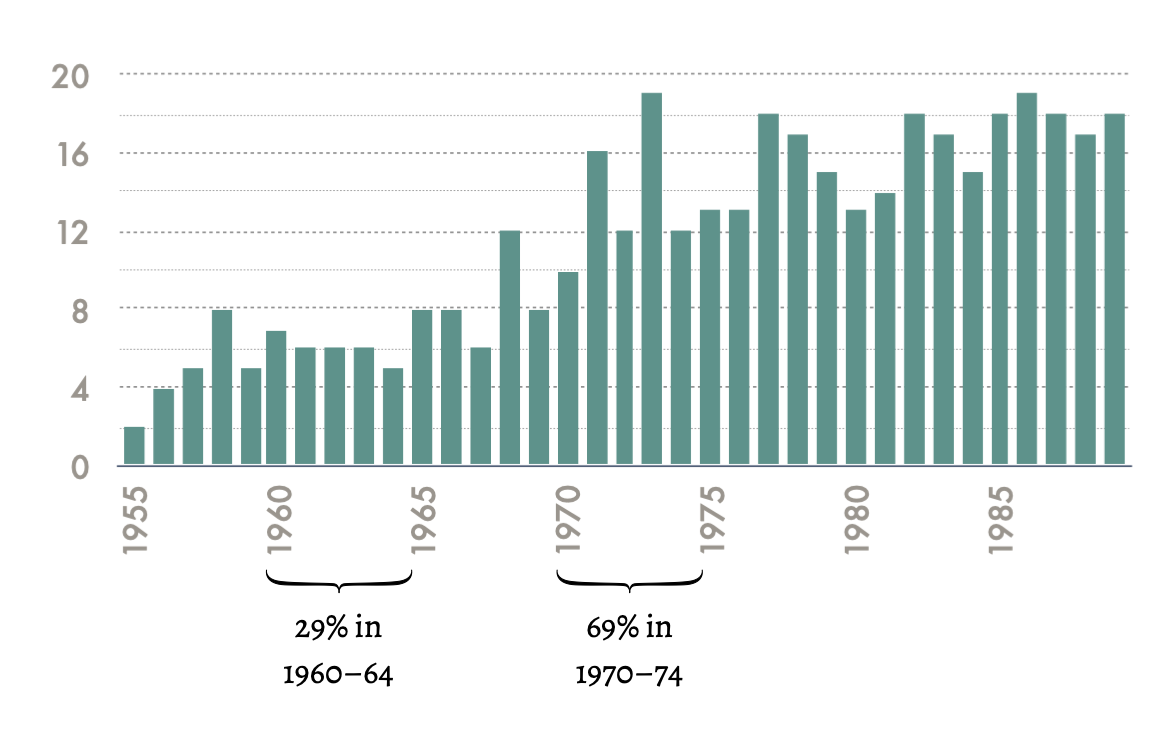

Example 1 gives two graphs showing the incidence of particular form types in the rock and pop repertoire. These graphs use data from Jay Summach’s study of the top 20 songs on Billboard’s year-end charts from 1955 to 1989 (Summach 2011, 2012). The top graph shows the combined incidence of AABA and strophic forms—the primary form types that do not contain a chorus—and the bottom graph shows the incidence of verse–chorus forms. These graphs visually demonstrate a trend that many writers have observed: between 1960 and 1970, rock shifted its preference from songs without a chorus to songs with a chorus (see Covach 2005, de Clercq 2012, von Appen and Frei-Hauenschild 2015, and Temperley 2018, among others). Between 1960 and 1964, strophic and AABA songs made up 61% of the year-end top 20, with verse–chorus songs making up only 29%. A decade later, these proportions had essentially reversed, with 29% AABA and strophic forms and 69% verse–chorus forms in 1970–74. After 1974, these trend lines leveled off a bit, showing that the late 1960s were a significant transitional period that solidified rock’s preference for choruses.

Example 1. Between the 1960s and 1970s, rock shifted its preference from songs without chorus (AABA and strophic forms) to songs with chorus (verse–chorus forms).

Amid this transitional period in rock’s stylistic history, the Beatles were going through a stylistic transition of their own. In John Covach’s terms, they moved from an approach to songwriting as craft to songwriting as art (Covach 2006). The former dominated their releases through 1965, exemplified through a reliance on traditional song forms, especially the Tin Pan Alley-derived AABA form. Around 1965, the band began to depart from the craftsman approach, exemplified by their decreasing use of AABA form. The Beatles’ shift to an artist approach came to an explosive climax in May of 1967 with the release of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Among the many revolutionary aspects of this album, it is easy to overlook its near complete avoidance of AABA form. Avoiding AABA across an entire album was new for the Beatles; even the previous year’s Revolver, quite progressive in its own right, contained nearly half AABA songs. Mirroring the trend in rock music writ large, the Beatles’ abandonment of AABA led to an uptick in their use of verse–chorus forms. But the Beatles’ approach to verse–chorus forms was not the same as the mainstream standard that coalesced in the 1970s.1

To highlight the Beatles’ particular approach to verse–chorus forms, I focus on the relationship between musical form and lyrical narrative. I begin from the premise that verse–chorus designs derive from a song’s lyrical structure as much as from its musical features. In other words, verses and choruses represent different narrative functions as well as different formal functions. There are several different narrative relationships that can arise between verse and chorus, but typical verse–chorus songs display some sort of narrative hierarchy placing the chorus in the superior position relative to the verse. That is, the chorus’s lyrics describe the song’s main message, with the verse’s lyrics supporting that message in some way. While this chorus–verse hierarchy in both lyrics and music quickly became rock’s default, the Beatles took a different approach to narrative structure in verse–chorus forms. Rather than using the chorus as the lyrical focal point with supporting verses, the Beatles instead placed the two sections on relatively equal footing. Their verse–chorus narrative structures thus presented a general framework of opposition, the two sections portraying contrasting narrative worlds whose juxtaposition drives the song’s meaning.2

In the following section, I describe the Beatles’ relationship to verse–chorus form across their output, showing that the band’s use of the form peaked right as they entered their so-called “artist” period. I then discuss their particular approach to the form, which centers on the aforementioned principle of narrative opposition. To demonstrate the Beatles’ paradigm of narrative opposition, I analyze four songs recorded between November 1966 and April 1967 as part of the band’s Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album project. These six months were pivotal in the Beatles’ artistic development, rock’s stylistic evolution, and British and American cultural history: the band completed its transition from craft to art, rock embraced psychedelia and artist-based composition instead of professional Brill Building-style songwriting, and countercultural movements dominated the societal landscape, setting up the Summer of Love a few months later. As I describe below, the Beatles explored verse–chorus designs in these recording sessions more than they did at any other time. More broadly, on the Sgt. Pepper album, the Beatles began to think of a song’s form not as a basic template but as a central aspect of its expressive meaning, and their approach to verse–chorus designs treated the form as a vehicle for expressing certain lyrical ideas.3

1. The Beatles and Verse–Chorus Form

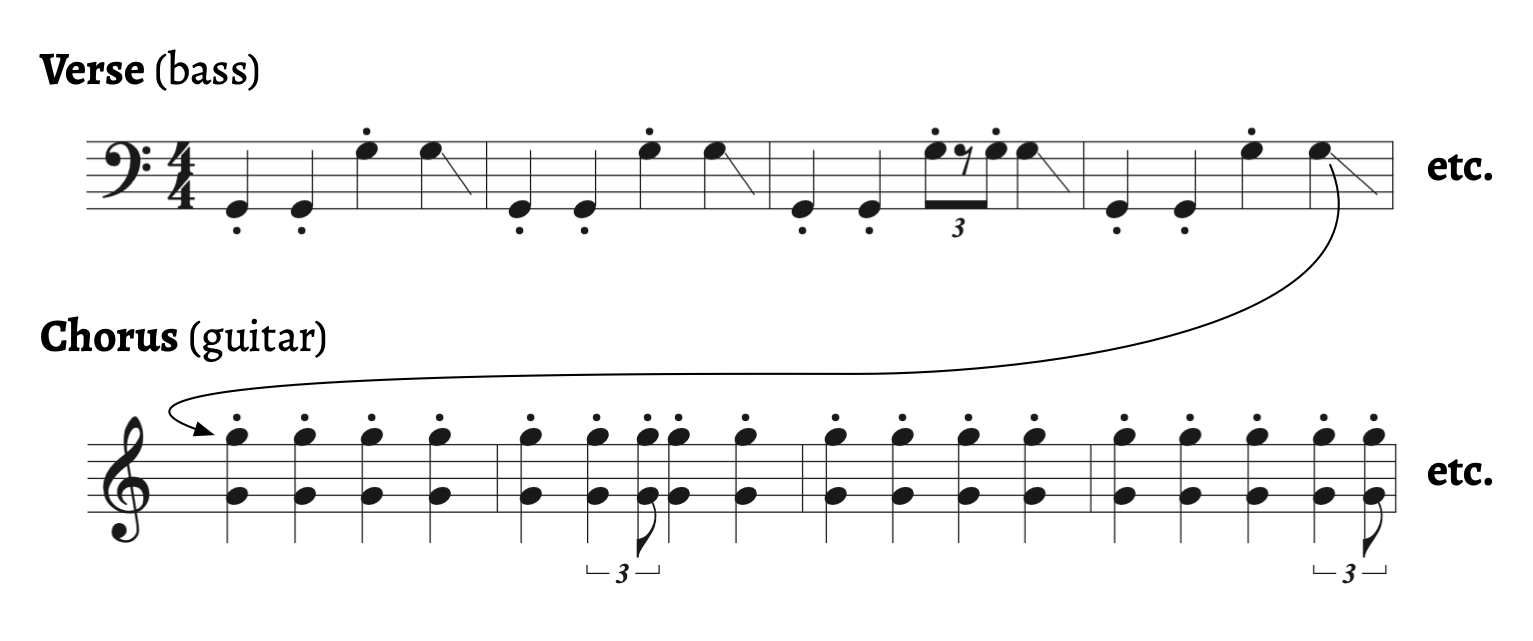

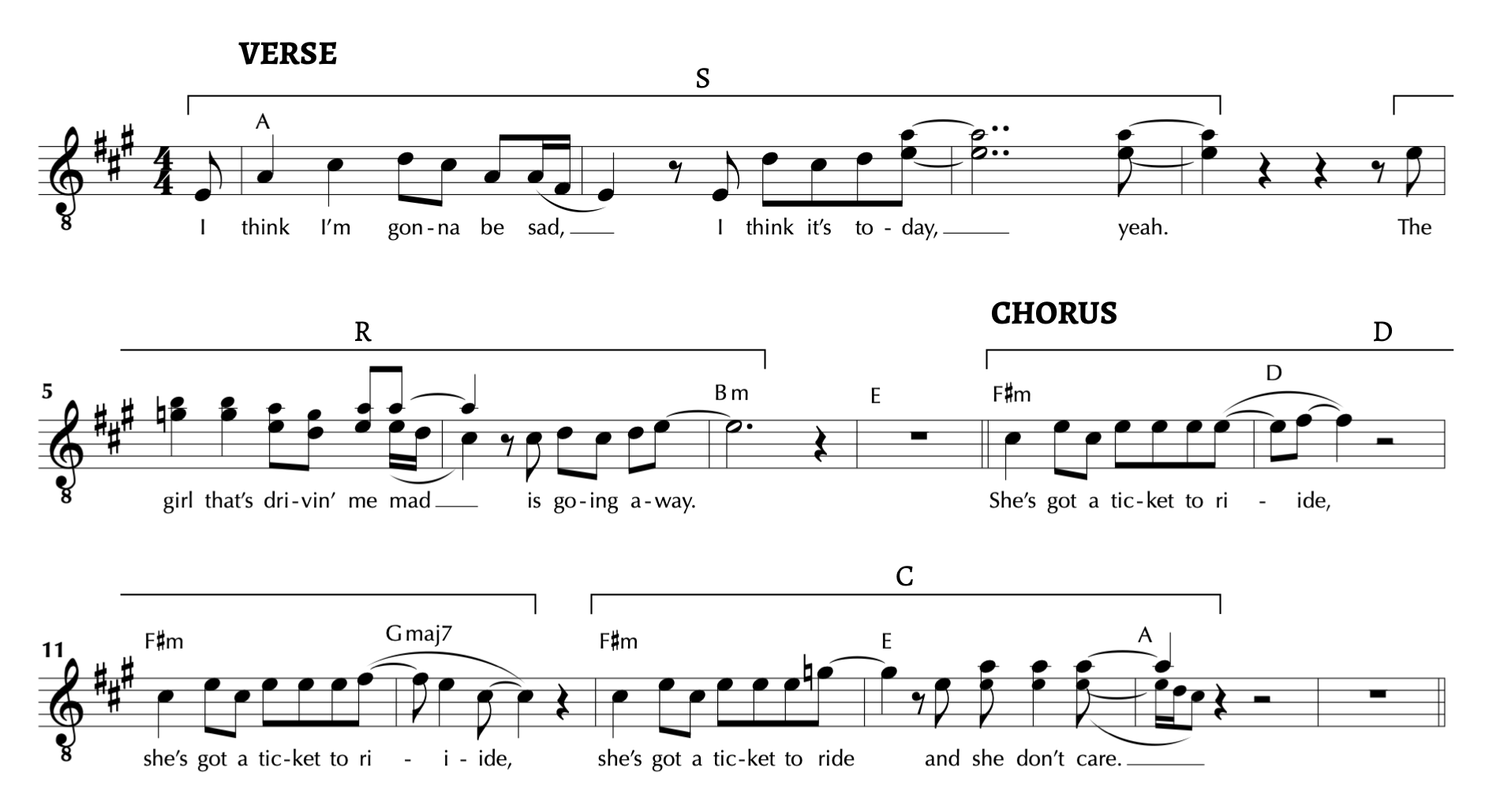

As Covach describes it, the Beatles’ progression from “craftsmen” to “artists” is traceable through their songs’ formal designs. In their early songs of 1963–1964, the Beatles relied heavily on the Tin Pan Alley-derived AABA form. Verse–chorus songs occasionally appeared, usually as album tracks rather than singles (“Any Time at All,” “Not a Second Time,” “Every Little Thing,” e.g.), but that form was clearly a secondary option. (An exception to the non-single trend is 1963’s “She Loves You,” which Covach interprets as a “faulty” AABA song in which what was intended as a bridge acted more like a chorus [Covach 2006, 43].) The group’s 1965 albums Help! and Rubber Soul began to offer a balance between verse–chorus and AABA designs. However, most verse–chorus songs on these albums represent what Covach refers to as “incipient” verse–chorus form, where verses within an overall AABA design begin to cleave apart into separate verse and chorus sections, “mostly under the force of a refrain that seems to have outgrown its role within the structural confines of the verse” (Covach 2010, 6–7).4 A clear example is Help!’s “Ticket to Ride,” shown in Example 2, whose eight-bar verse and eight-bar chorus could well have made up a single 16-bar section if the latter were not so self-contained with three statements of the title lyric. Note that the chorus begins away from the tonic harmony, here on the submediant F$$\sharp$$ minor—thus representing what I refer to as “continuous verse–chorus form” (2020, 179–198)—and the entire passage exhibits what Walter Everett has termed an “SRDC” phrase structure, with four four-bar melodic units displaying the progression statement–restatement–departure–conclusion (1999, 16). Similar incipient/continuous verse–chorus layouts underlie “Help!,” “Drive My Car,” “Wait,” and “Run For Your Life.”

The Beatles’ transition to the artist approach took a leap with their 1966 album Revolver, on which myriad innovations in recording technology opened up new avenues for artistic experimentation. But it was not until they returned to the studio in late 1966 that the band’s exploration of verse–chorus structures came to a head. From November to April, the band would record fourteen tracks, none of which followed standard AABA form, and more than half of which exhibited fully formed (non-incipient) verse–chorus structures.5 Twelve of these tracks would form Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, an album representing, in Walter Everett’s words, “a pinnacle of artistic vision, good times, and far-reaching impact far beyond its peers, such as could never again appear in any one product” (1999, 89). The other two tracks, “Penny Lane” and “Strawberry Fields Forever,” would be released separately as a double-A-sided single in February 1967. The band’s turn toward verse–chorus forms in the Sgt. Pepper sessions is more than a matter of numbers; rather, the verse–chorus structures in this period represent a new approach to the form, one tied to a specific expressive framework and lyrical paradigm.

That paradigm, as mentioned, is narrative opposition, wherein verse and chorus explore contrasting subjects or viewpoints. The Beatles, that is, treated the verse–chorus formal layout as an expressively marked form, one whose purpose is to support a specific narrative framework. Though verse–chorus structures were fast overtaking AABA as rock’s go-to formal design, the Beatles never treated the form as a default, instead viewing it as one of many options chosen in response to a song’s particular expressive needs. Indeed, though verse–chorus structures pervade the Sgt. Pepper album and their 1967 singles, the form did not stick in the ensuing Beatles output the way it did in the broader rock repertoire. From 1968’s Magical Mystery Tour onward, the band seemed more interested in exploring novel, experimental formal designs as they had in Sgt. Pepper’s closing track “A Day in the Life,” as seen for instance in the White Album’s “Happiness is a Warm Gun” (1968) and the medley from Side 2 of Abbey Road (1969). In addition, as John Covach points out, the Beatles continued to explore the possibilities of AABA form even as other rock artists turned away from it, as in “Two of Us,” “I’ve Got a Feeling,” and “The Long and Winding Road,” all from their final album Let it Be (1970) (Covach 2006, 49). Verse–chorus form is certainly not absent from the Beatles’ post-Sgt. Pepper output—it is found, for example, in “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,” “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,” and “Across the Universe”—but after their intense exploration of the form in 1966–67, it became just another tool in their formal repertoire, used only when needed.

2. Chorus–Verse Hierarchy

A narrative framework based on opposition does not necessarily place the chorus in the central, hierarchically superior role that is typical. Theorists generally describe the chorus as the primary focal point within a verse–chorus song, the section around which the rest of the song revolves. John Covach tells us explicitly that “if a song has a chorus, that chorus is always the focus of the tune” (2010, 6), and others remind us that choruses tend to have higher energy (Stephan-Robinson 2009, 94), contain more dramatic harmonies (Everett 2009, 145), and demand more of our attention (de Clercq 2012, 40) than their respective verses. Much of what directs our focus toward the chorus is musical, as opposed to lyrical. The most salient aspect is texture: choruses tend to add multiple singers (hence the word “chorus”), shift from hi-hat to ride cymbal in the drums, add more distortion on the guitars, and increase the “loudness” in comparison with the verse. Other musical factors may come into play as well, such as the length of melodic units (they tend to be shorter in choruses), the rhythm of the vocal line (choruses tend toward longer notes), or the degree of musical closure (stronger in the chorus), etc.6

The lyrical elements most associated with choruses are lyrical repetition—choruses tend to contain the same lyrics in each iteration, while verses change their lyrics throughout the song—and the inclusion of the song’s title, which often appears at the very beginning of the chorus. But the chorus–verse hierarchy is also clear, perhaps especially so, in a song’s poetic narrative. Broadly speaking, choruses tend to “sum up the song’s main theme,” as Walter Everett notes (2009, 145), whereas verses more often give detail or tell a story (Nobile 2020, 71). There are various ways in which a song’s lyrics can display this general principle. Many songs present different stories in each verse, related by a central theme summarized in the chorus—in Jimmy Buffett’s “Margaritaville,” for instance, the various scenes of booze-soaked tropical slackery in the verses are summed up with the chorus’s line, “wastin’ away again in Margaritaville.” In other songs, the chorus adds context that causes us to hear the verses differently—in the Temptations’ “Just My Imagination,” for instance, the idyllic relationship described in the verses’ scenes is, in the chorus, revealed to be a mere figment of the narrator’s imagination. Some songs shift the narrative voice from verse to chorus, the chorus acting as a sort of song within a song that the verse’s narrator hears—in the Eagles’ “Hotel California,” for instance, the verses give first-person accounts of falling prey to Los Angeles’s hedonistic allure, represented metaphorically as the titular hotel, while the choruses give the siren song of the personified hotel, beckoning the protagonist to his irreversible fate.

These lyrical paradigms, generally speaking, support the framework of a central chorus with supporting verses, as described above. In all of them, the chorus carries the song’s main narrative idea—we might need the verses to understand that idea, but once we get it, the chorus’s lyrics sum it up on their own.7 The Beatles, on the other hand, take a somewhat different approach to the lyrical relationship between verse and chorus. Instead of a summarizing chorus with contextualizing verses, the Beatles place the two sections in narrative opposition, the two sections portraying contrasting narrative ideas whose juxtaposition drives the song’s poetic meaning. The result is that the hierarchical relationship between chorus and verse is not so explicit, at least within the text. Instead of summarizing or explaining the verses’ stories, the chorus provides a counterpoint to the verse. The song’s meaning thus arises not out of any individual section but rather from a synthesis of the two opposed worlds.

The idea of verse and chorus as structurally equivalent is, to some extent, contradictory. That is, once we interpret a given section as a chorus, we implicitly deem it the song’s main section. (Or maybe it’s the reverse: once we choose which section is the main one, we ascribe to it chorus function.) Put another way, the only way for two alternating song sections to identify themselves as verse and chorus is for one—the chorus—to be perceived as hierarchically superior to the other. None of the Beatles songs I analyze in this paper exhibit any significant ambiguity as to which section is the chorus, and it is not so difficult to identify several elements that give those choruses more of a focal quality than their respective verses. In “Penny Lane,” for instance, the choruses have longer notes, more backing vocals, less chromaticism, and higher melodic pitch than the verses, all of which arguably draws attention more toward the former than the latter.8 I do not mean to argue that there is no perceptible hierarchy between chorus and verse in the songs I analyze. I do, however, contend that these songs’ poetic frameworks are not dependent on one section being the lyrical focal point, which differentiates these Beatles songs from the mainstream default that coalesced in the 1970s. Furthermore, as I demonstrate in the analyses below, these songs’ musical features project less of a strict chorus–verse hierarchy than is typical, supporting the lyrical opposition through various musical contrasts. In other words, music and lyrics give us enough hierarchical information to identify one section as the chorus and another as the verse, but the central concern is more about contrast and opposition.

3. Analyses

In the remainder of this article, I analyze four songs from the 1966–67 Sgt. Pepper recording sessions: “Penny Lane,” “Getting Better,” “Lovely Rita,” and “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” All four songs have what I consider to be clear verse–chorus structures (“Lucy in the Sky” includes a prechorus as well), and each presents a different type of narrative opposition in its verses and choruses. My primary analytical claim is that the lyrical framework of opposition described above is supported by elements of musical opposition. In other words, lyrics and sound synchronize to present two contrasting and opposed sections whose alternation provides the song’s main structural impetus. As I describe, the two sections unproblematically project the formal functions of verse and chorus, but the chorus is not the unequivocal focal section as in most verse–chorus songs after 1970.

3.1 “Penny Lane”

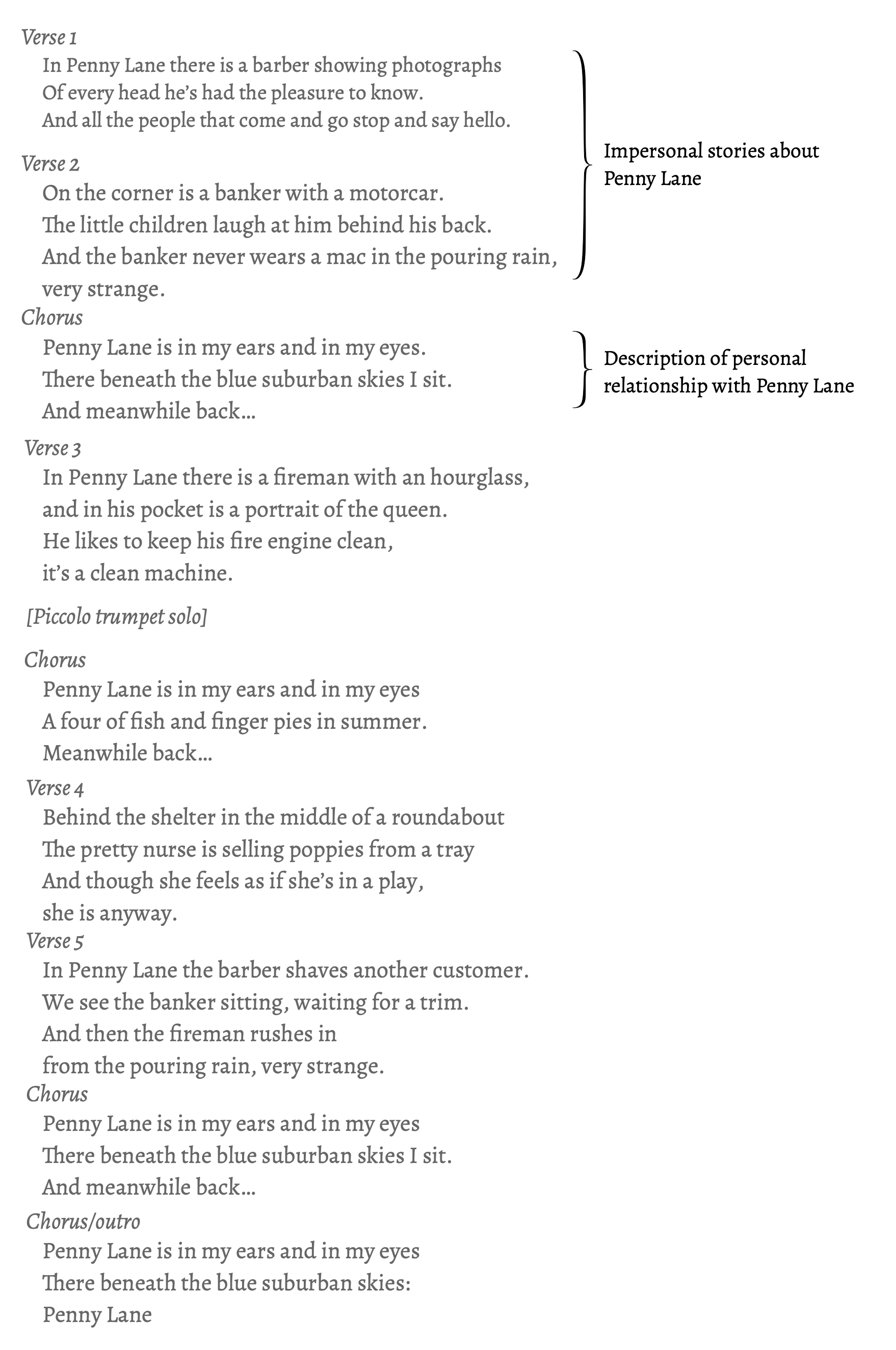

“Penny Lane,” along with its flipside “Strawberry Fields Forever,” kicked off the Sgt. Pepper recording sessions in November 1966. Example 3 displays the song’s lyrics. In the verses, Paul McCartney speaks impersonally about the Penny Lane neighborhood of Liverpool. Though the tone may be nostalgic, the stories about the barber, the fireman, the banker, and the nurse are from the perspective of an observer; this is the way Penny Lane is and the way it always will be. But in the choruses, the lyrics shift to the first person (“Penny Lane is in my ears and in my eyes”) and the descriptive discourse disappears; McCartney tells no more stories, but instead gets lost in nostalgic reverie. The texts in verse and chorus display Raymond Monelle’s distinction between “progressive time” and “lyric time” (Monelle 2000, Chapter 4; see also Klein 2004, 37–38). In essence, progressive time represents time passing while lyric time represents time arrested. Walter Everett further points out that the chorus of “Penny Lane” “shifts perspective from the pure narration of local events to the author’s subjective (‘foggy’) memories” (Everett 1999, 86). Importantly, it is clear that McCartney’s narrator is not, at the present moment, in Penny Lane—as Matt BaileyShea has discussed, the line “there beneath the blue suburban skies I sit” followed by “and meanwhile back in Penny Lane” places McCartney outside of Penny Lane, further differentiating the narrative worlds of verse and chorus (BaileyShea 2021, 168–169).

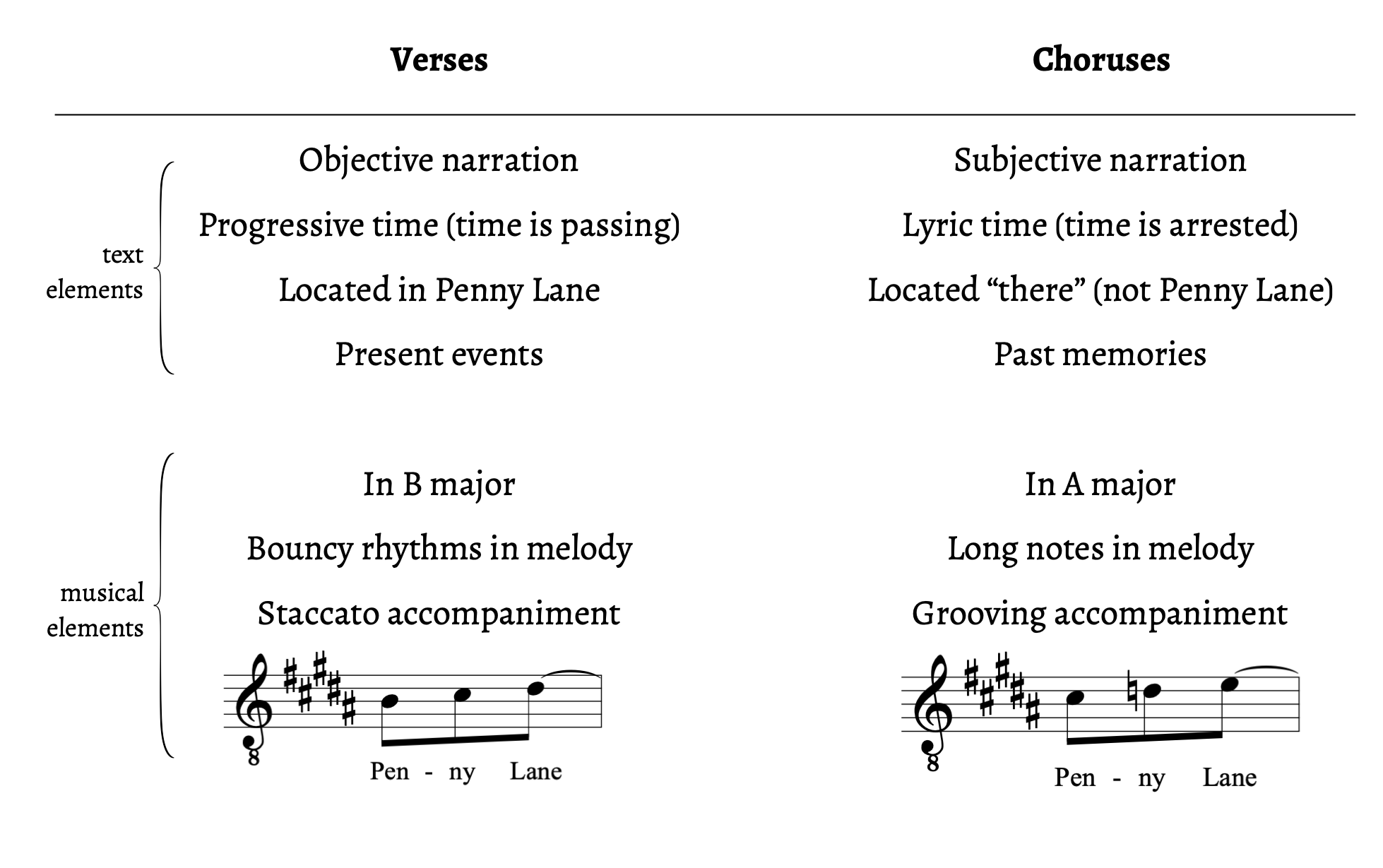

Lyrically speaking, then, the move from verse to chorus is reflected in moves from objectivity to subjectivity, passing time to arrested time, Penny Lane to an unidentified “there,” and present to past, as tabulated in Example 4. Such moves clearly set the two sections in narrative opposition. Juxtaposing these opposed sections as verse and chorus in a single song, though, creates what BaileyShea describes as “lyrical tensions” (2021, 169), and we are led to search for some way of synthesizing the narrative opposition to resolve these tensions. In other words, the opposition does not simply remain an opposition—rather, we begin to read each section through the other, thus constructing a higher level of meaning than that of either section alone. The choruses’ personal reflections bring a new perspective on the verses’ scenes: we realize that these are not objective observations from an omniscient narrator but rather imagined situations dreamed up by McCartney’s nostalgic persona (perhaps the nurse’s “play” mentioned in the fourth verse?). Conversely, the picture of Penny Lane we get from the verses frames our understanding of McCartney’s narrator: this is someone brought up in an unassuming and intimate suburban area of Liverpool, where interactions among quirky characters were a main source of entertainment. This narrator thus lays claim to a particular brand of authentic Britishness, one far removed from the cosmopolitan, psychedelic, and globe-trotting public image of the Beatles in early 1967. Though it is important not to fully equate song personas with their performers, it is not a stretch to read “Penny Lane” as McCartney honing his image as a down-home Liverpudlian who just happened to make it big but never forgot his roots.

The song’s musical features reflect the lyrics’ opposition between verse and chorus. The lower portion of Example 4 summarizes the contrasting musical elements between the two sections. Most prominent is the whole-tone modulation from B major in the verse to A major in the chorus, which many writers have cited as a reflection of the text’s oppositions (Everett 1999, 86; BaileyShea 2021, 171; Temperley 2018, 208). That is, B major is the domain of Penny Lane, while McCartney’s inner thoughts reside in A major—and when the song’s final chorus is transposed up to the verses’ key of B major, Penny Lane and McCartney’s narrator are brought together in a musico-narrative moment of transcendence. Alongside this tonal shift, the contrast between progressive and lyric time is borne out in the two sections’ rhythmic profiles; the verses are punctuated with staccato quarter notes in the piano and lilting triplet rhythms in the vocal melody, suggesting an active temporality, while the chorus has a laid back, grooving accompaniment with long, held notes in the melody, suggesting a more reflective state. With the shift in agency, perspective, and time, one wouldn’t be blamed for missing the motivic relationship between statements of the title lyric: “Penny Lane” at the beginning of the verse takes us from B to D$$\sharp$$ while “Penny Lane” at the beginning of the chorus takes us from C$$\sharp$$ to E in the same rhythm (see Everett 1999, 86). The motivic relationship solidifies the two sections’ roles as opposing points of view on the eponymous neighborhood.

The story of “Penny Lane”’s verse–chorus form is opposition and synthesis. Though linked by the narrative theme and melodic motive of Penny Lane, the two sections portray distinct narrative worlds. The song thus asks us to integrate the two opposed sections into a broader meaning. Is the song about the neighborhood of Penny Lane or about its relationship to McCartney’s narrator? The quick answer is both, with the verses focusing on the former and the choruses on the latter. More deeply, though, the song tells us that Penny Lane and our narrator are not so easily separable. The stories we’re hearing of Penny Lane are filtered through McCartney’s mind and memories—not objective reality but a “play” directed by the song’s narrator—and McCartney himself has been formed by his deep personal relationship with the titular neighborhood. As we have seen, musical features reinforce the sense of opposition between verse and chorus, with the chorus not the song’s singular musical focal point but rather a natural counterpoint to the verse, in a different key and with a different feel.

3.2 “Getting Better”

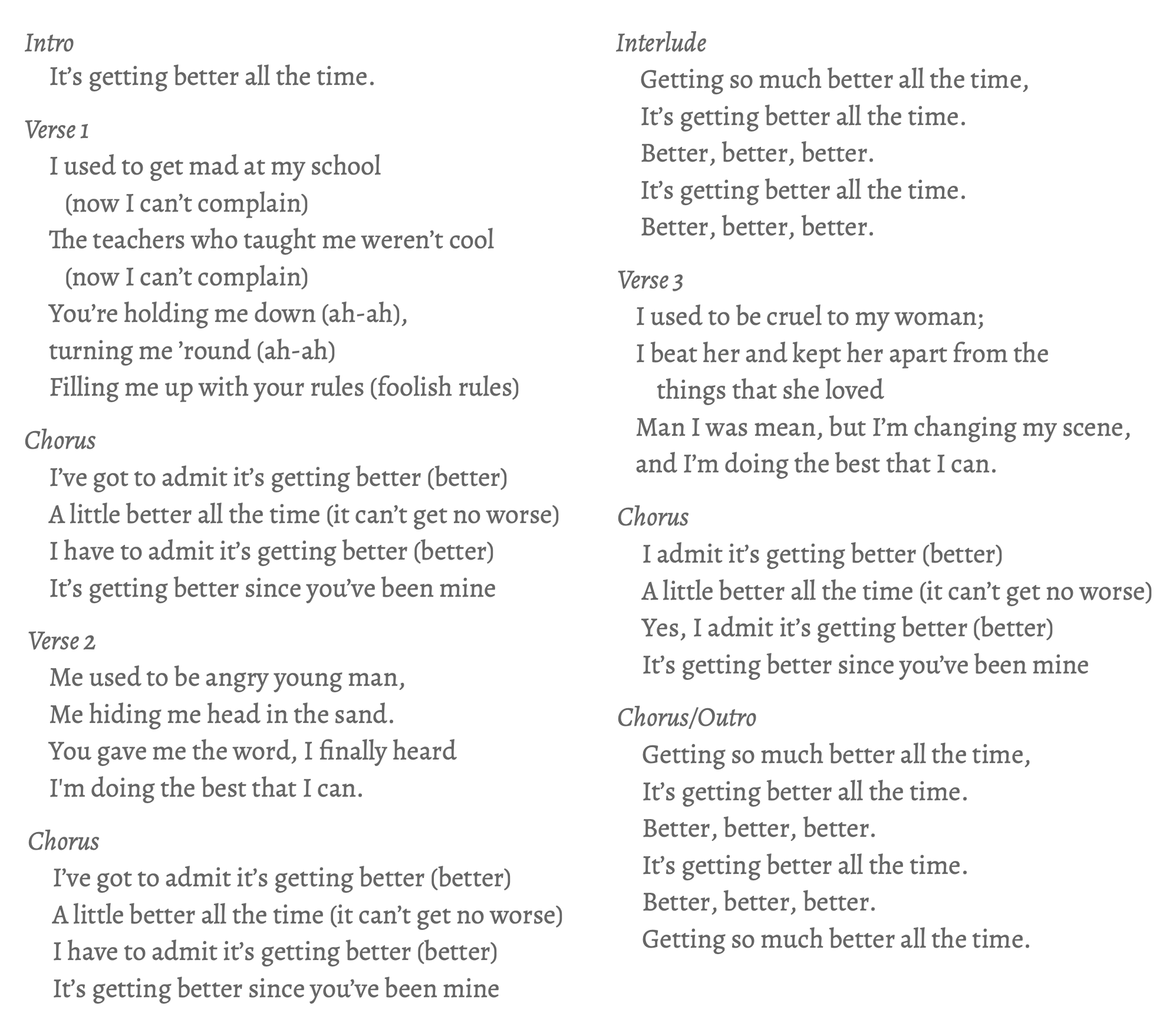

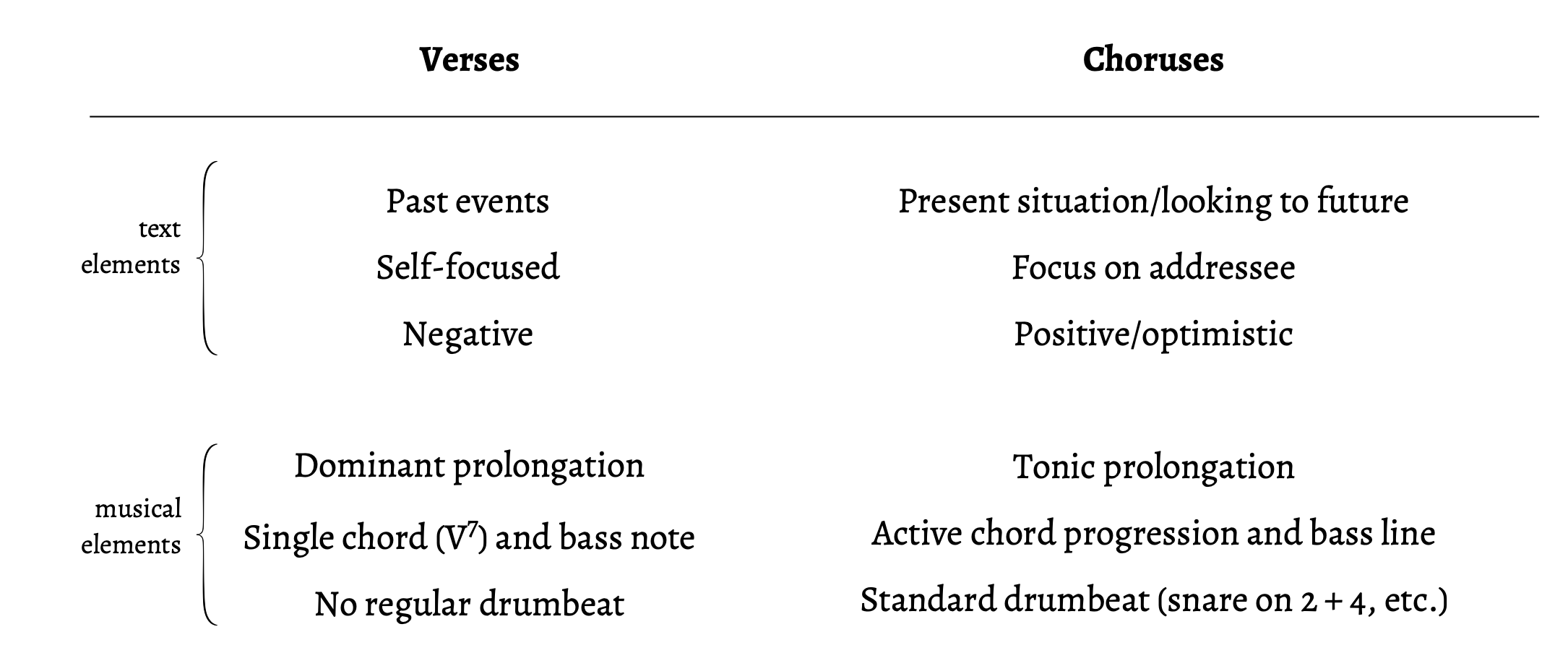

“Getting Better,” an unabashedly positive Paul McCartney offering spiced with some John Lennon sardonicism, sets negative descriptions of the past in verses alongside optimism about the future in the choruses. The song’s lyrics are given in Example 5, and a summary of the oppositional elements between verse and chorus appears in Example 6. The text focuses specifically on a shift in perspective on the part of the song’s narrator rather than any objective difference between past and present. In the verses, the narrator describes his prior actions, revealing an angry and confrontational outlook: in the first verse, he recounts challenging his schoolteachers’ authority; the second verse describes his self-isolation; and the third disturbingly reveals engagement in domestic abuse. In the choruses, we might expect that the narrator will tell stories of how he is now deferential, communal, and respectful, but that type of clear-cut transformation is not the story here; instead, things are simply “getting better all the time.” The text does not imply that any past problem has necessarily been solved, nor that the narrator’s personal improvement is anything more than incremental. The crux of the opposition seems to be a change in mindset set off by the introduction of some unnamed addressee—the “you” in “since you’ve been mine.” A reasonable assumption is that this “you” is a new lover, but there might be some reason to explore alternative interpretations. For instance, the references to “my woman” in the third verse seem out of place in a conversation directed toward a current lover, and the choruses’ preface “got to admit” implies some initial skepticism that whatever he is talking about would have any positive effect. In a 1980 interview, Lennon admits that the text’s references to domestic abuse are autobiographical, saying, “That is why I am always on about peace, you see. It is the most violent people who go for love and peace. . . . I am a violent man who has learned not to be violent and regrets his violence” (Sheff 1981). So perhaps the “you” that spurs the protagonist’s self-reexamination is not a specific person but rather an inner enlightenment reflecting the late-’60s ideals of peace and love.

Whatever the addressee’s specific identity, we can see an overall narrative opposition in verse and chorus between the “old me” and the “new me”—between a cynical, isolated, violent youth and an enlightened soul working toward inner peace. As with “Penny Lane,” neither section alone explains the song’s meaning; rather, the opposition itself is the meaning, with the comparison between old and new driving the song’s narrative. As the song goes on, “Getting Better” begins to mix in some of the chorus’s present/positive content into the verses—the second and third verses end with the line “I’m doing the best that I can,” for instance—showing that the protagonist’s positive thinking has begun to color how he thinks of his past transgressions.

Musically speaking, the verses and choruses contrast in many ways, reinforcing the lyrics’ narrative opposition. The verses are set to a persistent dominant pedal in the bass with a stuttering, syncopated drum beat and sparse guitar riffing. The choruses see the harmony switch to a bouncy tonic prolongation, with an active, “walking” bass line and a standard rock beat with snare hits on beats 2 and 4. The unsettled dominant bass pedal from the verses is thrust upward into bell-like guitar octaves, recontextualizing this pedal tone within the more optimistic tonic context, as shown in Example 7. That is, both verse and chorus focus on the note G, the former in the bass and the latter in an upper register; the Gs dominate the harmony in the verses, not allowing the bass or anything else to escape the V7 chord, but float above the chord progression in the chorus, still there but less of a dominating force. In the same way, the protagonist’s inner anger used to dominate his personality, but after the change he is able to keep it at bay—though it is not yet eradicated.

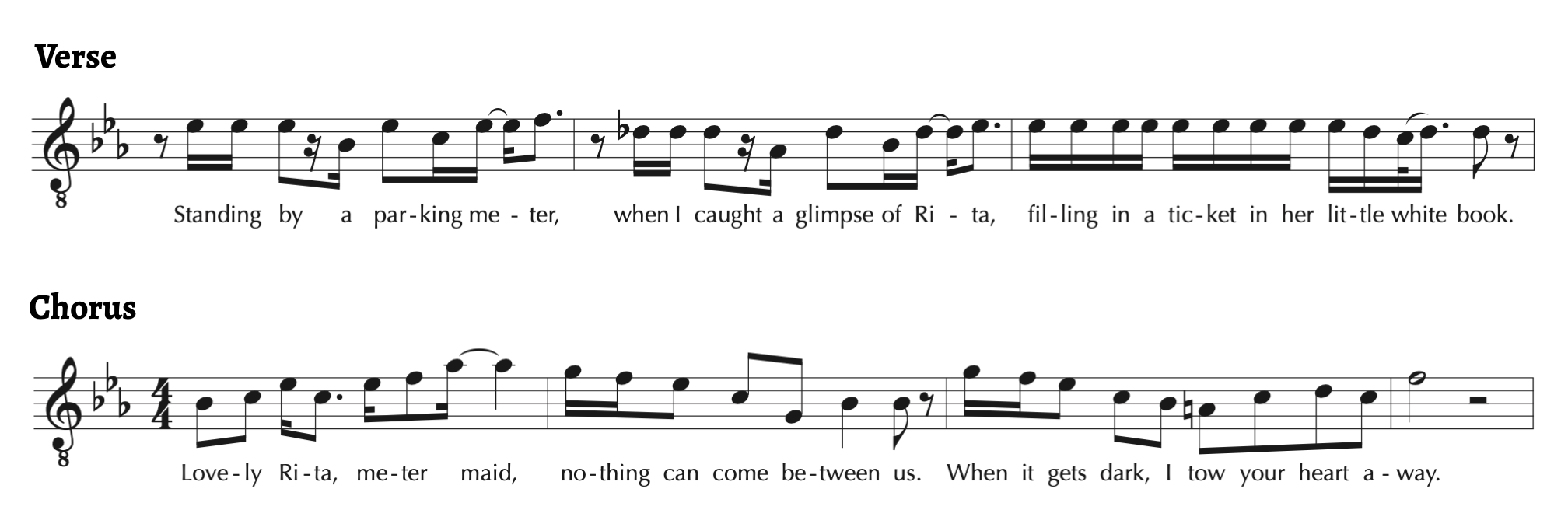

3.3 “Lovely Rita”

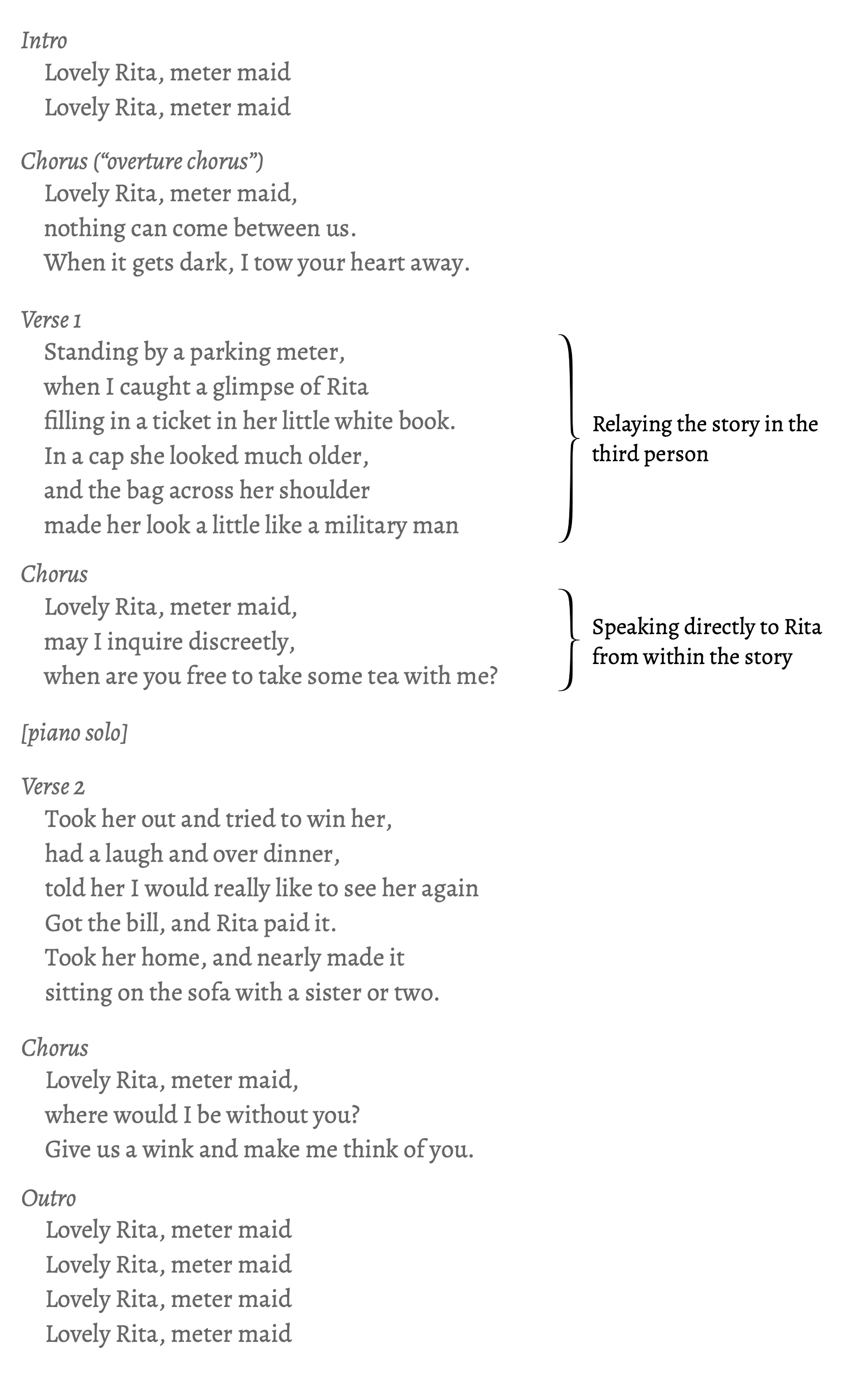

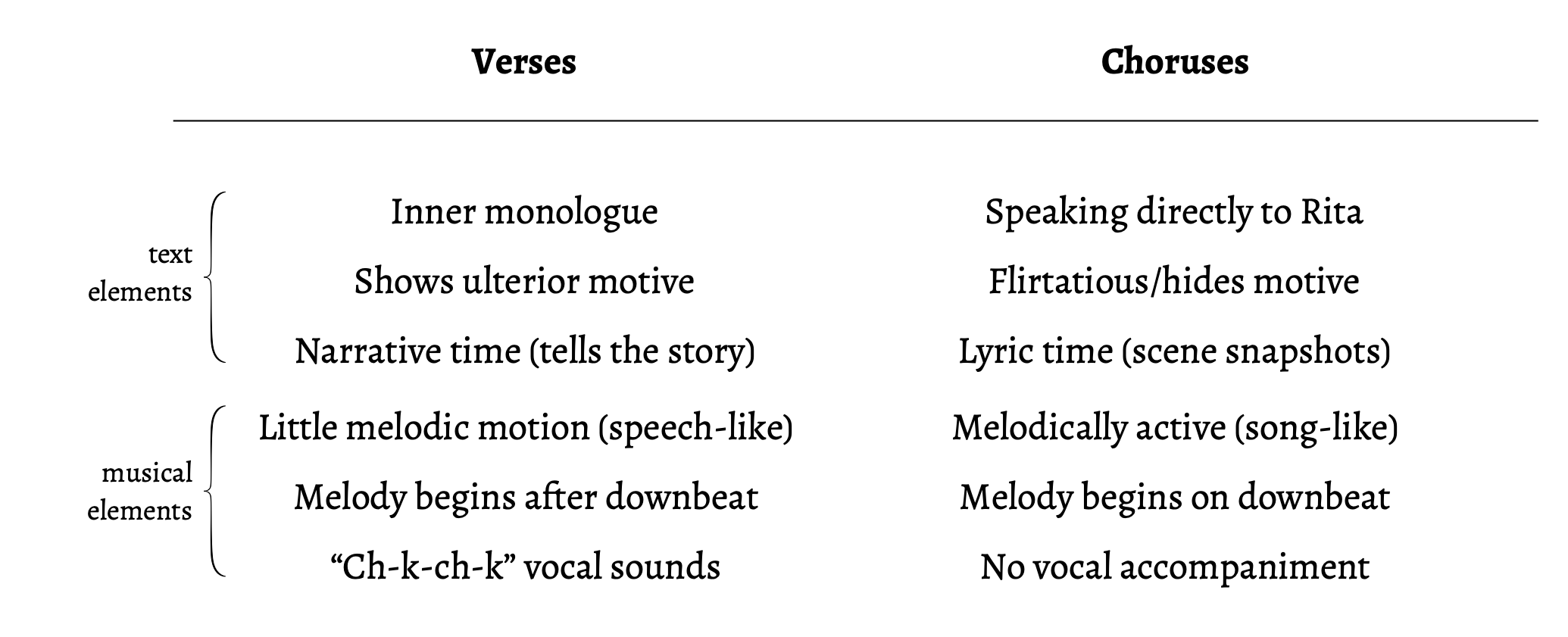

“Lovely Rita” is one of McCartney’s so-called “novelist” songs (see MacDonald 2005, 102), here a fictional recounting of a tryst with a municipal worker. Example 8 gives the song’s lyrics, which make clear that the protagonist’s designs on Rita do not arise from true infatuation but rather a predatory curiosity about romantic involvement with a meter maid. Example 9 summarizes the oppositional elements in verse and chorus. McCartney presents the story in two distinct forms of address, which correlate with the two contrasting song sections. In the verses, McCartney soliloquizes, relaying the story in the past tense and referring to Rita in the third person, as if recounting the encounter to a group of friends. The song’s two verses present the story in two acts: the first describes the narrator’s reaction to seeing Rita preparing to give him a parking ticket, and the second tells of their ensuing date and the narrator’s nearly successful attempt to “make it” with Rita, so to speak. The verses notably reveal the narrator’s less-than-pure motives—it is clear that even in “hav[ing] a laugh” and telling her “I would really like to see her again,” the narrator is not being sincere but instead is merely “tr[ying] to win her.”

A third-person story like this in the verses could easily lend itself to the standard lyrical layout with the verses’ story alternating with a summary of the main message in the chorus, but that is not exactly what we get here. Instead, the choruses present scenes from within the story, as our protagonist speaks directly to Rita, who is now addressed using the second person. In these choruses, the narrator turns on the charm, attempting to reel Rita in with lines like “may I inquire discreetly when you are free to take some tea with me?” and “give us a wink and make me think of you!” Unlike typical choruses, these present different lyrics each time, as if our narrator is trying out different flirty lines in the hopes that one will lead to the desired outcome. The chorus is in fact the first section we hear (after the intro’s “Lovely Rita, meter maid” awash in harmony and tape echo), and this initial, “overture” chorus (Nobile 2020, 120–121) clues us into the deviousness of the attempted flirtation we are about to witness with the groan-worthy pickup line “I tow your heart away.”

The distinct forms of address in “Lovely Rita” do not situate the chorus as the song’s central section. Instead, they place the two sections in narrative opposition: the verses present the narrator’s inner perspective, while the choruses present his outward actions directed at Rita. There’s an almost filmic quality to the narrative here, where we see the protagonist telling us a story in the verses and cut to a scene from the story itself for the choruses. Since there is no literal visual element to this song, these snaps between forms of address are communicated via the formal opposition of verse and chorus sections. Indeed, though in spoken or written discourse it might be confusing to shift from the third to second person when referring to Rita, such moves are common in popular songs, especially between different formal sections; Matthew BaileyShea relates such shifts to what he terms the “double address,” wherein the singer is simultaneously addressing the addressee (as “you”) and the listening audience (where the addressee is “she”; see BaileyShea 2014, 21–28). Again, as in both “Penny Lane” and “Getting Better,” neither verse nor chorus alone gives us a clear picture of what the song is about; the song’s meaning must be read through the two sections’ narrative opposition.

Over this narrative opposition, the musical differences between verse and chorus are relatively understated. The two sections on the whole sound quite similar; there is no textural shift into the chorus, nor is there a noticeable increase in energy, drama, or attention. The differences that are there reflect the text’s opposition: the verses contain very little melodic motion, mimicking speech inflection in odd three-bar groupings, contrasting with the choruses’ sing-songy melody, now with symmetrical four-bar groups, as the protagonist puts on a show for Rita (Example 10). (To Allan Moore, the chorus’s catchy melody is “typical McCartney,” while the verse is “more like Lennon”; see Moore 1997, 48.) Lennon’s overdubbed ch-k-ch-k vocal sounds add to the sense of time passing in the verse, contrasting with the “lyric time” of the chorus as we pause for a scene snapshot.9

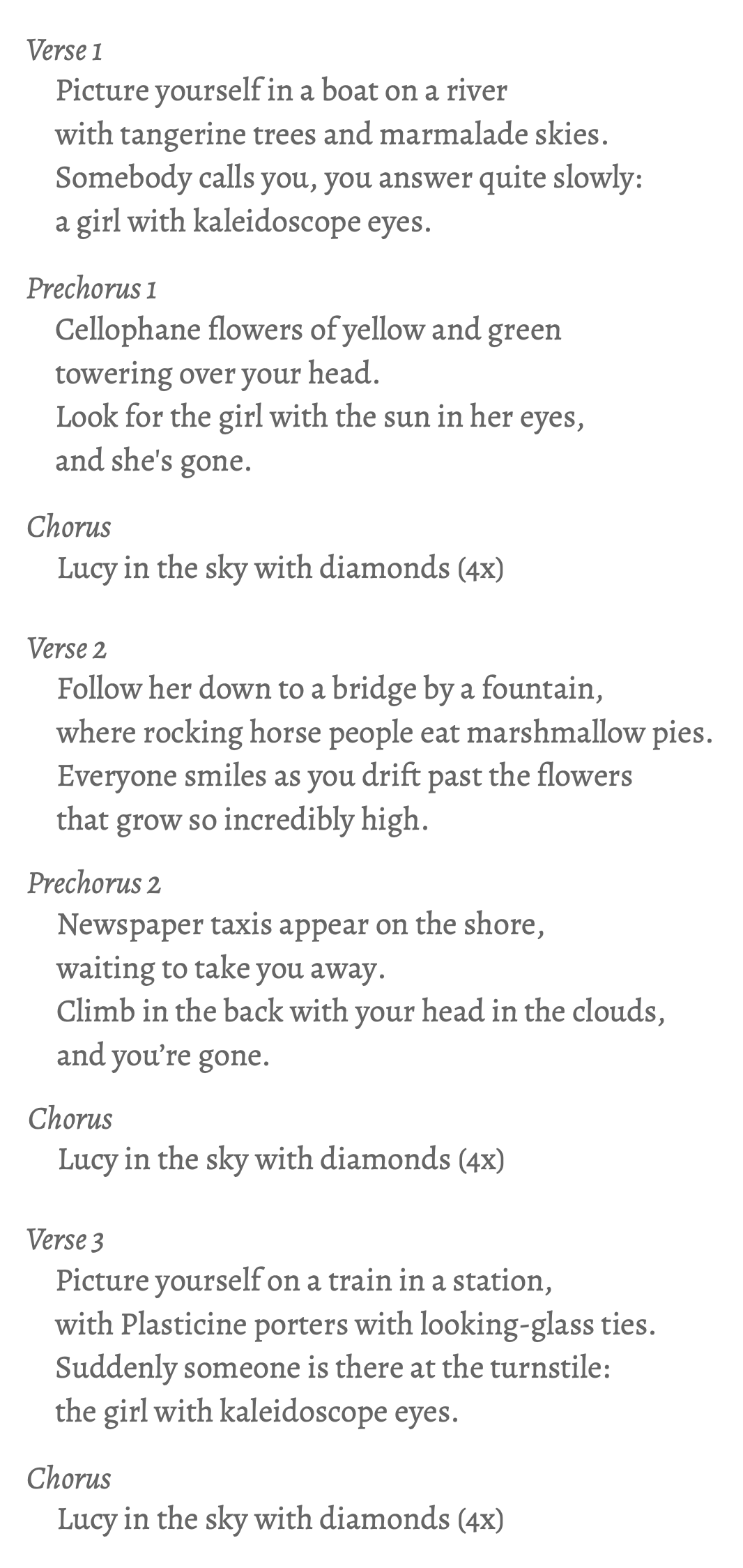

3.4 “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”

The three Beatles songs I have looked at so far were all written primarily by Paul McCartney. The oppositional approach to verse–chorus form is also apparent in John Lennon’s songs from the Sgt. Pepper period, though Lennon’s lyrics tend toward the abstract and thus their meaning is often somewhat opaque. In “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” whose lyrics are shown in Example 11, the verses and prechoruses paint fantasy images of tangerine trees and marshmallow pies while the choruses give us the single line “Lucy in the sky with diamonds.” Lennon always maintained that the song had no intentional drug references, claiming not to have noticed that its title forms an acrostic for the initials LSD (see Everett 1999, 104), but given the Beatles’ well-documented involvement with hallucinogenics, many remain unconvinced. In any case, Lennon has acknowledged the text’s basis in Lewis Carroll’s surrealist writing, especially Through the Looking Glass; so, as Walter Everett summarizes, “whether dream-based, drug-based, or both, the song’s amphibolous phantasms entice the listener away from all concerns with reality” (Everett 1999, 104).

“Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” is one of the few Beatles songs that include a prechorus section between verse and chorus. This song’s prechorus largely serves as harmonic and melodic development, taking us from the verse’s A-major world (with melodic emphasis on C$$\sharp$$) through the chord progression B$$\flat$$–C–F–B$$\flat$$–C–G–D (with sustained melodic emphasis on D), the final chord of which acts as the dominant to the chorus’s G-major tonality.10 Lyrically, the prechoruses group with their preceding verses, adding further details to the surreal imagery already conjured. In the first cycle, the verse invites the listener into a fantasy world and introduces the psychedelic character of a girl with kaleidoscope eyes. After our attention is drawn to giant flowers in the prechorus, the girl disappears along with the melody on the word “gone.” This final word returns at the end of the second prechorus, which had invited us to leave our drifting boat and climb into a newspaper taxi, but now it is us, the listener, who is gone. Immediately following the word “gone” in both prechoruses, three drum hits knock us out of our dreamworld and the song abruptly pivots to a mainstream-rock style for a chorus section whose text simply repeats the title lyric “Lucy in the sky with diamonds.”

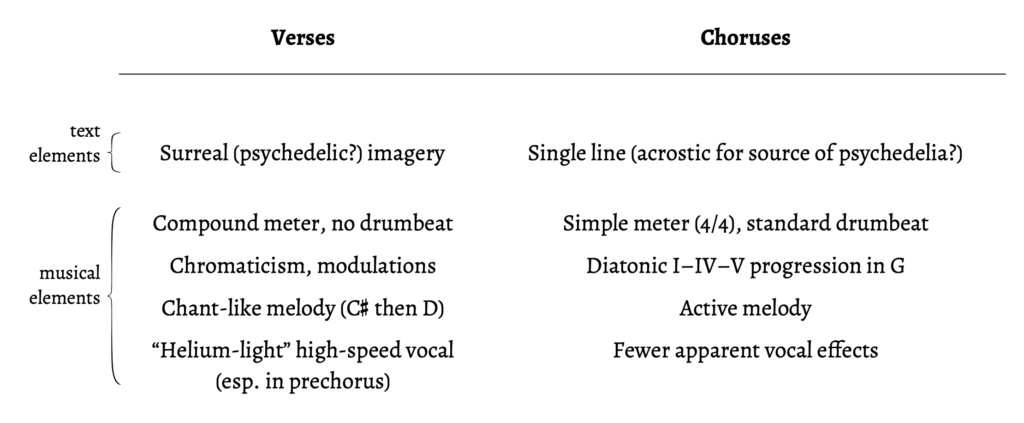

Despite cryptic lyrics, “Lucy in the Sky” can be read as presenting the narrative opposition of unreality versus reality. That the verses and prechoruses represent unreality is rather clear from their fantastical evocations. But the chorus’s single line of text does not exactly signal a snap back to reality. Instead, that shift comes largely from musical elements, as shown in Example 12. Several musical elements support the verses’ and prechoruses’ depictions of unreality, including the Lowrey organ’s meandering chromatic lines, Lennon’s chant-like vocal line played back at high speed giving it a “helium-light” quality, and copious reverb on everything, all set over a drumbeat-less compound meter.11 In the chorus, all of this gives way to a basic 4/4 rock beat underlying a standard I–IV–V chord loop with an active melody that eventually acquires a descant harmony line in thirds. In Ian MacDonald’s words, this “clodhopping” shift “shatters the lulling spell the track has taken such pains to cast” (MacDonald 2005, 103), as if the dreamworld evaporates before our eyes and we are once again surrounded by mundane reality.

This musical opposition detaches the chorus’s single line from the surreal imagery of the verses and prechoruses. Though the image of a girl named Lucy floating in the sky surrounded by diamonds would be perfectly at home among the tangerine trees, marshmallow pies, and Plasticine porters evoked in the verses and prechoruses, its musical context encourages us to read Lucy as a more concrete idea. We could take the literal route, noting that the title came from Lennon’s son Julian’s description of a preschool drawing, to read the chorus as depicting the real-life object that led Lennon to conjure the verse’s and prechorus’s surreal scenes. Slightly more abstractly, we could follow Wilfrid Mellers’s suggestion that the song acts as a “revocation of the dream-world of childhood” to posit a chorus wherein the adult world somewhat rudely intrudes upon youthful imagination (Mellers 1973, 89; see also Moore 1997, 33–34). It is only a small step from there to the drug-based reading—ignoring Lennon’s denials—wherein the verses and prechoruses describe a psychedelic world entered through the chemical portal identified in the chorus’s acrostic. In all of these readings, the chorus represents a real-life source of the unreality depicted in the verses and prechoruses, a mainstream-rock conduit to a fantasy world of chromaticism, exotic instruments, and trippy studio effects. Such a reading is in fact not an inapt metaphor for the Beatles’ career up to that point.

Conclusion

“Verse–chorus form” is an odd term. At a basic level, it simply refers to any song that contains a chorus section (since the presence of a chorus implies the presence of a verse; see Nobile 2020, 72), and thus distinguishes itself from AABA form, strophic form, and others that do not contain choruses. As we have seen, since the mid 1960s, the vast majority of mainstream rock and pop songs have contained choruses. Does this mean that most rock and pop songs are in the same form? My answer to that is both yes and no: yes, in the sense that all these songs alternate verses and choruses, but no, in the sense that there is significant variety in how the component sections relate to one another. For instance, I have demonstrated elsewhere how different harmonic designs lead to different formal processes, showing that what we call verse–chorus form refers to at least three distinct formal-harmonic paradigms (Nobile 2020, esp. 148–150). In this article, I have argued that lyrical narrative can have a similar effect on our perception of form: different poetic structures create different relationships among song sections, which strongly affects how we perceive the song’s formal process.

In particular, I have made the case that as the Beatles entered their “artist” period, they used verse–chorus form as a vehicle for a specific narrative paradigm, one based around narrative opposition between the two sections. Unlike most later verse–chorus songs, the Beatles’ songs did not give the chorus an unequivocal focal role, but instead drew our attention to the relationship between the two sections’ contrasting texts. I should note that an oppositional lyrical design is well at home in an AABA form, where the bridge’s lyrics often demonstrate a narrative idea that contrasts with those of the verses. David Heetderks has demonstrated that the Beatles often frame their AABA songs in this way, showing how differences in text scansion and rhyme between verses and bridges can reflect different psychological states (2022; see also Fitzgerald 1996). In this way, even as the Beatles departed from AABA form as they entered their artist period, they might have brought along some stylistic elements from the craftsman era.

I should note that not all of the Beatles’ verse–chorus songs exhibit narrative opposition. Even within the Sgt. Pepper sessions, other approaches to the form are evident. “She’s Leaving Home,” for instance, reflects the more normative paradigm of stories in the verses and overall theme in the choruses: this song’s verses describe scenes surrounding a young girl’s escape from her parents’ home while the choruses draw out the summative title lyric “she’s leaving home,” interspersed with self-reflective commentary from the girl’s parents. “With a Little Help from My Friends”—presented as an offering from a particular member of the album’s titular band—exhibits Covach’s incipient verse–chorus form, where the verse–chorus cycles resemble single verses whose refrains are substantial enough to cleave off into their own section, thus forming the chorus. In this song, the verses comprise two parallel melodic groups, suggesting the first half of an SRDC phrase structure, and the verse–chorus cycle as a whole coheres harmonically and melodically, as Walter Everett demonstrates in a Schenkerian graph (Everett 1999, 103). Other narrative frameworks arise now and again after Sgt. Pepper as well: in “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,” the chorus presents a sort of big-picture motto (“life goes on, brah”) for the song-long story of Desmond and Molly; and “Hello Goodbye” puts the meaningful disagreement in the chorus (“you say goodbye, and I say hello”), which explains why the verses list other seemingly mundane disputes. Overall, what is clear is that the Beatles never used a verse–chorus design as a neutral formal template, instead treating it as an expressively loaded structural framework. Form, in other words, was to them an integral part of a song’s meaning. As John Covach has chronicled, the Beatles’ transition from a craftsman approach to an artist approach is traceable in their innovative approach to formal structure (2006); in this article, I hope to have made the case that their synchronization of form and narrative meaning was an especially central aspect of this transition.

References

BaileyShea, Matthew L. 2014. “From Me To You: Dynamic Discourse in Popular Music.” Music Theory Online 20 (4).

———. 2021. Lines and Lyrics: An Introduction to Poetry and Song. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Burns, Lori. 2005. “Meaning in a Popular Song: The Representation of Masochistic Desire in Sarah McLachlan’s ‘Ice.’” In Engaging Music: Essays in Musical Analysis, ed. Deborah Stein, 136–148. New York: Oxford University Press.

Covach, John. 2005. “Form in Rock Music: A Primer.” In Engaging Music: Essays in Musical Analysis, ed. Deborah Stein, 65–76. New York: Oxford University Press.

———. 2006. “From Craft to Art: Formal Structure in the Music of the Beatles.” In Reading The Beatles: Cultural Studies, Literary Criticism, And The Fab Four, ed. Kenneth Womack and Todd F. Davis, 37–54. Albany: SUNY Press.

———. 2010. “Leiber and Stoller, the Coasters, and the ‘Dramatic AABA’ Form.” In Sounding Out Pop: Analytical Essays in Popular Music, ed. Mark Spicer and John Covach, 1–17. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

de Clercq, Trevor. 2012. “Sections and Successions in Successful Songs.” PhD diss., Eastman School of Music.

———. 2017. “Embracing Ambiguity in the Analysis of Form in Pop/Rock Music, 1982–1991.” Music Theory Online 23 (3).

Everett, Walter. 1999. The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver through the Anthology. New York: Oxford University Press.

———. 2009. The Foundations of Rock. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fitzgerald, Jon. 1996. “Lennon-McCartney and the ‘Middle Eight.’” Popular Music and Society 20 (4): 41–52.

Heetderks, David. 2022. “Norms of Textual Scansion and Rhyme in Beatles AABA forms.” Music Theory Spectrum 44 (1): 41–62.

Klein, Michael. 2004. “Chopin’s Fourth Ballade as Musical Narrative.” Music Theory Spectrum 26 (1): 23–56.

MacDonald, Ian. 2005. Revolution in the Head: The Beatles’ Records and the Sixties. Third revised edition. London: Pimlico.

Mellers, Wilfrid. 1973. Twighlight of the Gods: The Beatles in Retrospect. London: Faber & Faber.

Monelle, Raymond. 2000. The Sense of Music: Semiotic Essays. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Moore, Allan F. 1997. The Beatles: Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Neal, Jocelyn. 2007. “Narrative Paradigms, Musical Signifiers, and Form as Function in Country Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 29 (1): 49–72.

Nicholls, David. 2007. “Narrative Theory as an Analytical Tool in the Study of Popular Music Texts.” Music & Letters 88 (2): 297–315.

Nobile, Drew. 2011. “Form and Voice Leading in Early Beatles Songs.” Music Theory Online 17 (3).

———. 2020. Form as Harmony in Rock Music. New York: Oxford University Press.

Osborn, Brad. 2013. “Subverting the Verse/Chorus Paradigm: Terminally Climactic Forms in Recent Rock Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 35 (1): 23–47.

Sheff, David. 1981. Interview with John Lennon and Yoko Ono. Playboy, January. Transcribed online at http://www.beatlesinterviews.org/dbjypb.int3.html.

Stephan-Robinson, Anna. 2009. “Form in Paul Simon’s Music.” PhD diss., Eastman School of Music.

Stephenson, Ken. 2002. What to Listen For in Rock: A Stylistic Analysis. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Summach, Jason. 2011. “The Structure and Genesis of the Prechorus.” Music Theory Online 17 (3).

———. 2012. “Form in Top-20 Rock Music, 1955–89.” PhD diss., Yale University.

Temperley, David. 2018. The Musical Language of Rock. New York: Oxford University Press.

von Appen, Ralf, and Markus Frei-Hauenschild. 2015. “AABA, Refrain, Chorus, Bridge, Prechorus—Song Forms and Their Historical Development.” Samples 13. http://www.gfpm-samples.de/Samples13/appenfrei.pdf.

Notes

- Covach’s craft/art distinction should not be read as devaluing the Beatles’ early output in comparison with what came later. These terms refer to the Beatles’ own songwriting approach (in Covach’s estimation), not to any critical analysis of the songs themselves. Covach discusses how Lennon and McCartney initially saw the Beatles as a fad but expected their songwriting careers to continue long after the fad had passed (37–38); they considered themselves much more like Carole King or Phil Spector than like Elvis Presley or Franki Valli.

- My analytical approach is similar to that taken by Jocelyn Neal (2007), who identifies various narrative paradigms in verse–chorus songs in 1990s-era country songs.

- David Nicholls identifies “kinetic narratives” (i.e., stories that develop across the song) as a primary lyrical strategy in Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, in contrast to the Beatles’ earlier reliance on descriptions of static situations (e.g., “I Want to Hold Your Hand”). See Nicholls 2007, 308.

- See also Trevor de Clercq’s discussion of “formal conversions” (2012, Chapter 4), where certain organizational schemes can underlie single verses or a verse and chorus.

- There are eight songs from the Sgt. Pepper sessions that I believe are in a clear verse–chorus form: “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” “With a Little Help from My Friends,” “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” “Getting Better,” “She’s Leaving Home,” “Lovely Rita,” “Penny Lane,” and “Strawberry Fields Forever.” “Fixing a Hole” is arguably another example, though Walter Everett labels it as a verse/refrain plus bridge (i.e., as a version of AABA; see Everett 1999, 106–7). The five remaining songs all have some non-standard formal aspects that make them difficult to categorize unequivocally.

- For more on chorus markers, see Stephenson 2002, Chapter 6; Burns 2005, 138; Osborn 2013, 26–29; Temperley 2018, 158–166; and Nobile 2020, 71–73.

- In some songs, the verses’ context changes the chorus’s meaning. In Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the USA,” for instance, what seems like a patriotic ode is reframed as a biting indictment of the country’s mistreatment of working-class veterans. The paradigm Jocelyn Neal calls the “Time-Shift narrative” involves the chorus’s meaning changing each time it returns based on the verses’ different contexts—for example, Collin Raye’s country hit “One Boy, One Girl” reframes the title lyric to refer to teen lovers, those same lovers years later on their wedding day, and eventually their newborn twins (Neal 2007).

- David Temperley identifies twelve features that commonly differentiate chorus from verse, six of which apply to “Penny Lane”; see Temperley 2018, 159. Five of the remaining six features are not applicable to this song (e.g., “more sharp-side pitch collections [in relation to tonic],” as the two sections have different tonics), and only one feature flips the expected chorus/verse relationship (namely “faster harmonic rhythm,” which usually applies to choruses but here applies to “Penny Lane”’s verse). Not all of Temperley’s features necessarily increase the section’s focal quality—for instance, one chorus-signaling feature is “occurs second”—but many arguably do.

- With these similarities—as well as the chorus’s short (four-bar) length and its non-fixed lyrics—“Lovely Rita”’s chorus is not all that chorus-like, and one might be tempted to analyze it as part of the verse, or as something like a stand-alone refrain. To me, the section’s melodic profile and separability from the verses solidify its chorus function despite its short length: the catchiest, most memorable melody accompanies the title lyric here, and the section appears both with no preceding verse (in its first appearance) and with no subsequent verse (in its third appearance). See Nobile 2020, 70–73, and de Clercq 2017 for more on chorus function and identifying choruses.

- See Everett 1999, 104–105, for a detailed analysis, which offers a reading of the cycle’s overall harmonic design as an embellished II$$\sharp$$–V–I auxiliary cadence in G major.

- See Everett (1999, 104), and MacDonald (2005, 103), for more recording details.