Zachary Lloyd

Abstract

In Blue, Jeanine Tesori and Tazewell Thompson’s 2019 opera, a celebration of birth turns to the mourning of a teen’s senseless murder. Exploring the complexities of a shared Black experience in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, Blue focuses on a family whose son loses his life at the hands of his Father’s police officer colleague. While the score moves through various tonal spaces over the course of the opera, I examine Tesori’s specific use of the Lydian mode and the narrative implications that this mode’s usage carries. In Blue, the Lydian mode evokes extramusical associations with the supernatural, transcendence, and “sorrowful joy” demonstrating the possibility of a subtextual narrative reading in which the thoughts and desires expressed at the moment of the Lydian mode’s emergence will later be rendered impossible.

View PDF

Return to Volume 37

Keywords and Phrases: Jeanine Tesori, Tazewell Thompson, Blue (opera), Lydian Mode, Narrative Analysis

Sparked by conversations surrounding the public murders of unarmed Black persons by police officers in the United States, Jeanine Tesori and Tazewell Thompson’s poignant 2019 opera, Blue, serves as social commentary on contemporary issues of race and police violence.1 2 The libretto, written by Thompson, who is a Black playwright and director, explores the complexities of a shared Black experience as it relates to familial and communal relationships, parenthood, and the dangers of growing up Black in a world where white people have systematically created, enforced, and maintained an imbalanced power structure.3 Building on the growing Black Lives Matter movement, this opera also investigates the interwoven realities of when Blackness and law enforcement clash—both in public and within the home. 4

Matching the emotional breadth and depth found in the libretto, the opera’s score features a wide variety of compositional styles and regularly shifts among various pitch spaces including diatonicism, atonality, and modal centricity.5 In this opera, the Lydian mode is utilized explicitly by composer Jeanine Tesori to indicate an impossibility of sorts—that the sentiments expressed by the characters at the moment of the Lydian mode’s use are too good to be true.6 This aligns the Lydian mode with substantial narrative implications within the opera’s plot.

Following a brief description of the opera, including its characters and plot, I highlight historical and modern-day associations tied to the use of the Lydian mode. I then examine how Tesori employs the Lydian mode within Blue, creating subtextual narrative readings in which the thoughts and desires of the characters are rendered too good to be true.7

Plot Summary

As described by Seattle Opera, Blue presents a “portrait of contemporary African American life: of love and loss, church, sisterhood, and most importantly, family.”8 These themes develop throughout the two-act opera as a celebration of birth turns into the mourning of senseless death. The prologue immerses the audience within a dissonant soundscape, which transitions to police sirens as Father removes his hoodie and street clothes to don a police uniform.9 Scene I introduces Mother and her three Girlfriends as Mother shares the news that she has married a police officer and is pregnant with a boy. The Girlfriends berate Mother for her chosen spouse and state as a cardinal rule that “Thou shall not bring another black boy into this world.” Mother convinces the Girlfriends that everything will be fine, and they reluctantly bless her, her marriage, and her unborn child. Later in Act 1, Mother gives birth to her Son, and Father celebrates with his Police Officer Buddies. Through a scene transition, the audience watches Son grow up from a baby to a young child and then a teenager. The end of Act 1, specifically Scene 4, presents an argument between Father and Son. Son, now a local teen activist, was arrested for participating in protests, assumed to be connected to the Black Lives Matter movement. Father is upset that his Son has disrespected his profession while simultaneously putting his young life in danger.

Act 2 opens with Father at his local church, grieving the loss of his Son, who was shot by a fellow police officer at a non-violent protest.10 The Reverend cannot console Father, who quits the police force and turns in his badge. The Girlfriends are once again in Mother’s Harlem apartment as they attempt to comfort her in preparation for her Son’s funeral. Mother and Father mourn their Son at the funeral while the Reverend leads the congregation in a powerful hymn. In the epilogue, Father and Mother remember their final dinner with their Son before the fatal shooting. The dinner occurs after the fight the audience watched in Act 1, Scene 4. As Father and Mother return to the funeral, Son remains alone onstage. He sings of his plans to study art as the music fades to silence. With a final statement from Son, the lights fade to black, and the curtain lowers in complete silence.

Historical and Modern-Day Associations with the Lydian Mode

Associations between musical idioms and extramusical ideas have become a time-honored field of study within music theory. Extramusical associations have long been connected to the musical score, from exploring emotional connotations of the church modes in sixteenth-century performance practice to modern-day discussions of musical topics in film and music scholarship. Contemporary composers often rely upon their knowledge of various extramusical associations to evoke specific reactions in a listener. In Blue, Jeanine Tesori uses the Lydian mode to evoke specific extramusical associations of the supernatural, transcendence, and sorrowful joy, revealing the possibility of a subtextual narrative reading in which the thoughts and desires expressed at the moment of the Lydian mode’s emergence are later rendered impossible.

Tesori is hardly the first to rely on such extramusical associations. Anne Smith’s monograph exploring the connections between sixteenth-century theoretical writings and performance practice details each mode’s commonly held extramusical associations. Pulling from numerous historical theorists, Smith concludes that the Lydian mode was rather divisive. Several scholars wrote about the positive connotations of the Lydian Mode: Stephaneus Vanneus states that the Lydian mode brings delight and joy, Lanfranco describes Lydian as lively and suitable for dispelling cares from the spirit, and Finck links cheerfulness to the use of the mode (Smith 2011, 194-196). Other theorists, such as Nucius and Herbst, describe the Lydian mode as harsh and threatening though Smith notes that this may have been due to notational issues (Smith 2011, 197). The most intriguing are those theorists who find themselves in the middle of this spectrum. Gaffurius refers to the use of Lydian to accompany weeping and lamentation stating that the mode was initially formed to sweeten the sorrowful singers (Smith 2011, 194). Finck similarly refers to the healing properties of the mode: “joy of [the] sorrowful, revivifier of the desperate, [and] comfort of the afflicted” (Smith 2011, 196). Smith shows how complicated the historical associations of the Lydian mode were with scholars torn between associating it with positively and negatively valanced emotions.11

Recent scholarship in film and video game music studies has explored more specific implications of the Lydian mode within modern-day media. For example, Tom Schneller’s article on modal interchange in the music of John Williams examines the use of the Lydian mode and its narrative representation(s) in film. To Schenller, the Lydian mode—typically referenced using II\sharp

Considering both the historical emotional connotations and the modern-day extramusical associations of flight, magic, the supernatural, and transcendence is critical to understanding the culturally constructed meaning linked to the use of the Lydian mode. The mixed emotional implications lay the groundwork for similarly mixed narrative readings, while the topical associations allow composers to evoke specific supernatural and spiritual elements. Along with the above associations, the supernatural and the spiritual act as spearheads for something unreachable by mortals, while weightlessness may be viewed as a potential indicator of hope. In the following section, I examine how Tesori’s employment of the Lydian mode, both in its entirety and through localized harmonic inflections, pulls from these associations to create subtextual narrative implications related to the plot of Blue.12

It’s Too Good to be True – A Case Study of Tesori’s Use of the Lydian Mode

The remainder of this paper examines the presence of the Lydian mode including how localized modal inflections of the raised fourth scale degree occur within the opera. These examples highlight specific and critical moments of commentary within the opera’s plot: the Lydian mode serves as a subtextual form of foreshadowing indicating when something is simply impossible. The Lydian mode is first introduced during the conversation between Mother and the three Girlfriends in Act 1, Scene 1. The Girlfriends have discovered that Mother is pregnant with a Black boy, and they inform her that she must take him far away from the United States for safekeeping. In doing so, the Girlfriends are alluding to the dangerous nature of the United States for Black men. “Get yourself an island… Don’t be here… Take your boy to a place where he can be revered, not seared at the end of someone’s gun.” The Girlfriends’ harsh reactions offend Mother, and she cries out, “That’s not fair!” to which one Girlfriend responds, “What’s fair?”

Enter a waltz.

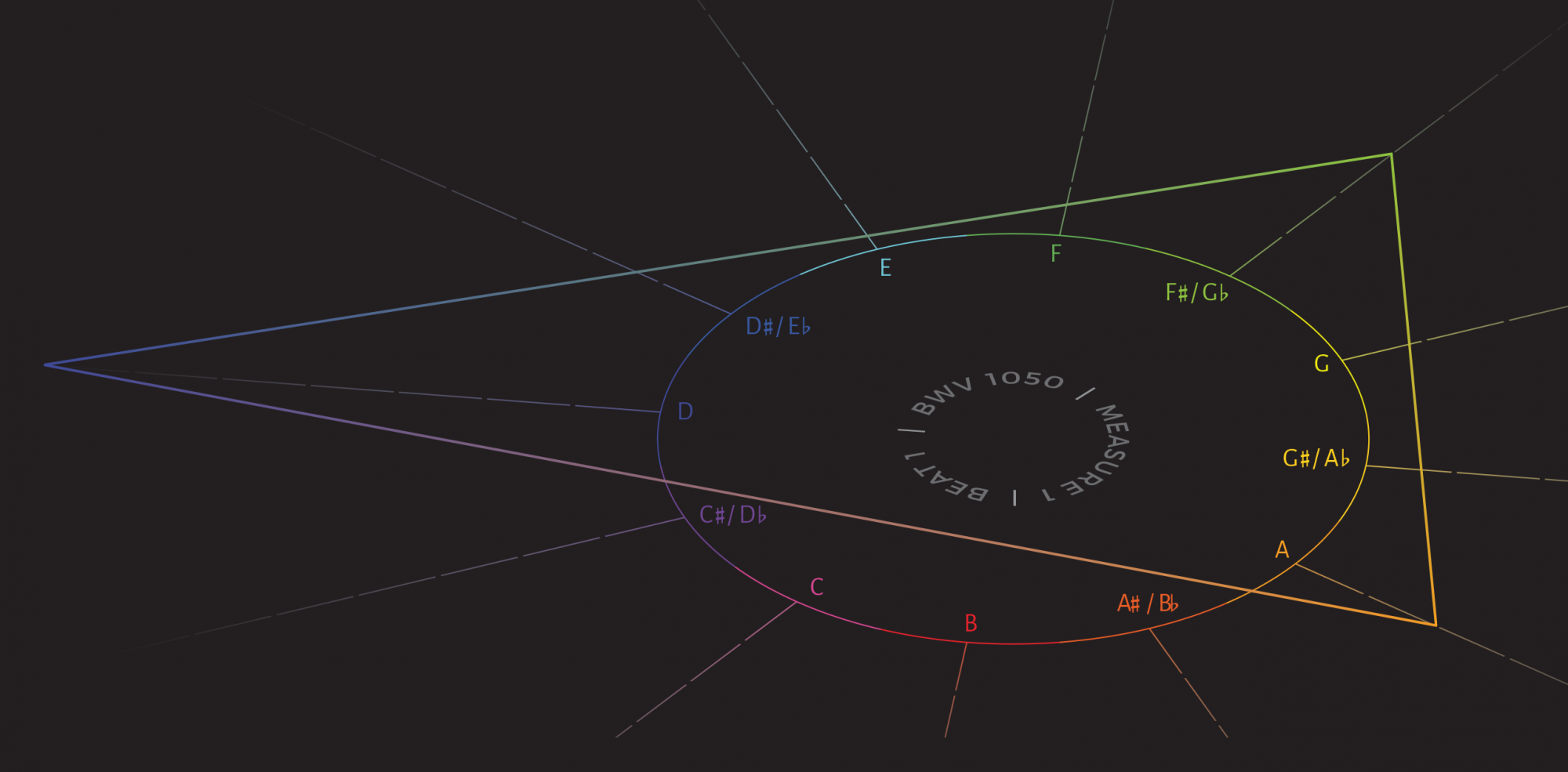

As shown in Example 1, a light waltz accompaniment emerges from the silence as the Girlfriends laugh at Mother’s response. The bassline establishes this A-major waltz figure by alternating tonic and dominant pitches.13 The upper strings pull towards the Lydian mode with the use of D\sharp

The waltz concludes as Mother erupts in an emotional recapitulation of previous material that spotlighted her love for her husband. However, this time, she sings that she is “having this boy… I’m keeping him close.” With this steadfast statement, the Girlfriends realize that nothing they say or do will sway Mother regarding her marriage to a police officer or her pregnancy. Mother requests that the Girlfriends bless her child, and, while reluctant at first, they do just that. The Girlfriends wish that the boy will be able to “stand tall before all others,” “know that [he] is wanted and loved,” and will “let the goodness within [him] flash a light on the darkened road.” These heartfelt wishes are set against an ascending scalar passage in the key of A-flat major, shown in Example 2. This recalls the sweeping gestures of the transcendence topic discussed by Atkinson and is similarly paired with momentary inflections of the Lydian mode. The Lydian mode, conjuring associations with the spiritual and the supernatural, is a reference to God—the intended recipient of the women’s prayers—and similarly represents the predetermined course of Son’s life that no mortal being can change. The passage begins solely in A-flat major, but soon the diatonic D\flat

The ascension theme also occurs at the end of Act 2, Scene 2. In this scene, Mother is mourning the loss of her child in her now-empty apartment. She sings a soliloquy begging for God to send her Son back to her—asking God to “Gather my baby in [your] embrace and bring my baby back to me.” As she reaches the end of the phrase, the score returns to the key of A-flat major, and the ascension theme begins again. This time, the Lydian alternation is markedly absent from the theme’s opening as Mother is helped off the floor by the three Girlfriends. As they slowly make their way offstage, the set transforms into the funeral service, and the first instance of \sharp\hat{4}

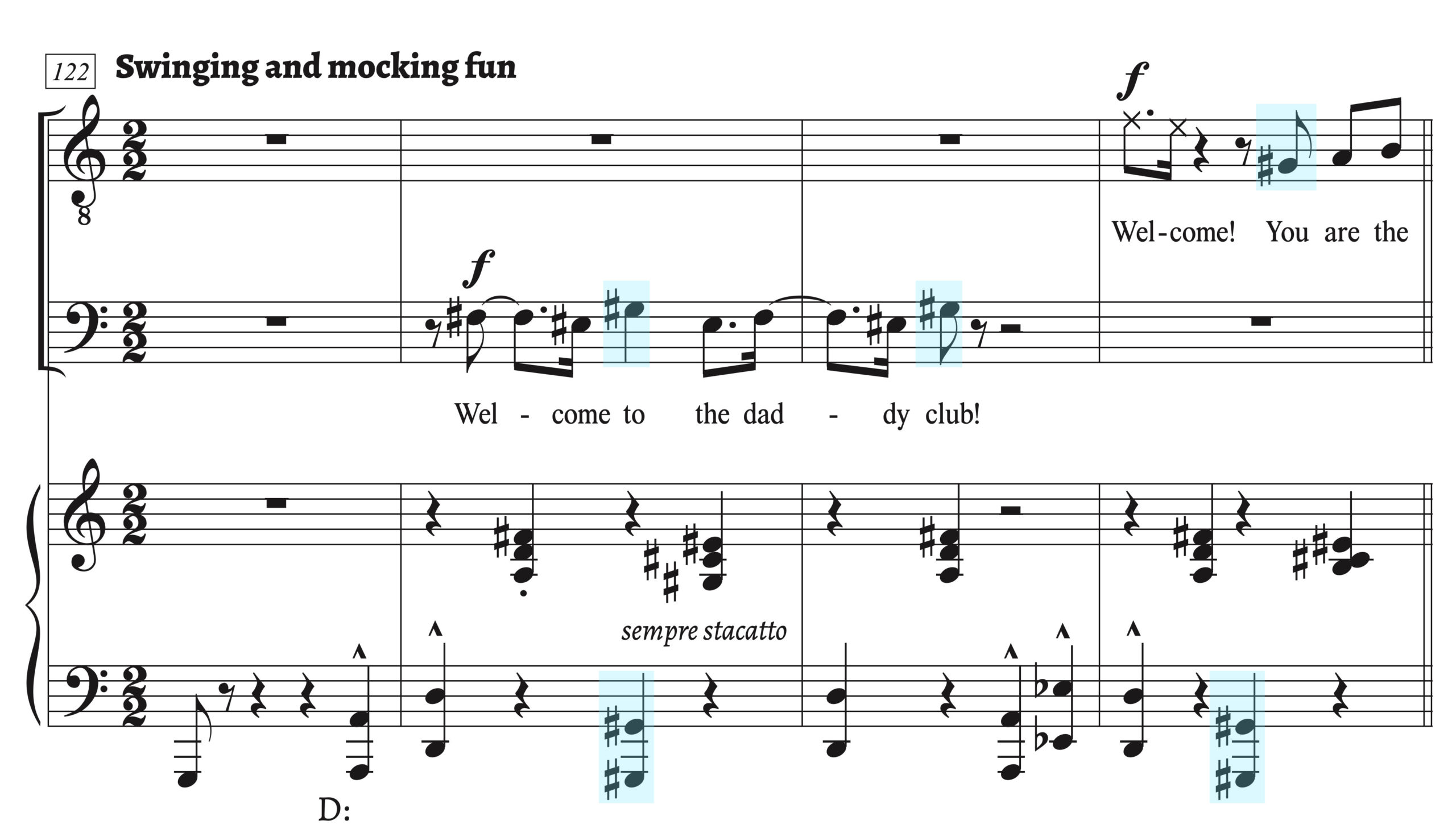

Other important Lydian moments of foreshadowing occur in the remaining scenes of Act 1. Act 1, Scene 2 has Mother and the Nurse teaching Father how to hold his Son. As the Nurse instructs Father how to cradle the baby, Mother proclaims her new status as a mother. Her lyrics, “I know who I am now. You gave that to me,” refer to the name Mother, her chosen title from that point forward. While the Nurse’s music is diatonic, Mother’s vocal line incorporates the raised fourth scale degree associated with Lydian as seen in Example 3. This Lydian inflection is linked to Mother’s statement of becoming a “mother” foreshadowing that this moment is too good to last, and she loses her son between the opera’s two acts. Act 1, Scene 3 also hints towards Lydian in the “Daddy club” sections shown in Example 4 where \sharp\hat{4}

The epilogue of Act 2 features a final example of Lydian mode.15 Time stands still in this scene as Mother and Father return home in a distant memory, while the ensemble remains frozen at the Son’s funeral service. Mother cooks in the kitchen, while Father and Son are heard off-stage having the same argument from Act 1, Scene 4. The epilogue returns to their final meal as a family before Son’s brutal murder. In an attempt to disarm the argument between the men, Mother turns their attention to all their favorite foods that she has prepared. Father and Son take a break from fighting as they focus on the delectable set-asides before them. Noticing the change in mood, Mother sings, “That’s it! We’re all together, just as we should be.” A final snippet of the ascension theme appears including the use of the Lydian mode’s raised fourth scale degree. This final statement can be seen in Example 6. Though brief, this two-measure statement is just enough for the audience to retroactively associate the use of Lydian with the same “impossible” and “too good to be true” connotations. These connections may not be made manifest for an audience member until this final moment, but the narrative implications of the Lydian mode become retroactively illuminated. This in part is due to the earlier uses of Lydian in association with lyrical content that is not proved impossible until much later in the opera. These final instances of Lydian thus allow the listener to retroactively associate their knowledge of the work at the end of the piece with the previous assertions of the Lydian mode.

Conclusion

This essay provides a case study of the narrative implications of Tesori’s use of the Lydian mode in the 2019 opera, Blue. As I have demonstrated, the use of Lydian foreshadows how something is too good to be true and, therefore, cannot last. Future research may explore other tonal and emotional relationships within the opera and may define a tonal-emotional spectrum within which the opera resides. I hope that future work on this opera will also include a critical analysis of how the opera represents Blackness on stage especially within a musical genre known for its largely white, upper-class audience.

Thompson’s libretto offers audiences the opportunity to see complex characters onstage—characters brought to life through Tesori’s score. Both Thompson and Tesori avoided stereotypes within the opera opting instead for a more complex story created through the lived experiences of Thompson and the Harlem residents he interviewed. Tesori notes that the situations with which the opera engages are not black or white likening them instead to a prism with new perspectives arising at every new angle further complicating the work.16 Her score for Blue reveals multidimensional characters who live through and grapple with real issues capturing the highs and lows of the main cast while representing an array of Black experiences. By not relying on stereotypes, Blue showcases the depth, richness, and humanity of a communal Black experience through Tesori’s score and the ingenuity of Thompson’s libretto.

References

Almén, Byron. A Theory of Musical Narrative. Musical Meaning and Interpretation. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008.

André, Naomi Adele, Karen M. Bryan, and Eric Saylor, eds. Blackness in Opera. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 2014.

Atkinson, Sean E. “Soaring Through the Sky: Topics and Tropes in Video Game Music.” Music Theory Online 25, no. 2 (July 1, 2019). https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.19.25.2/mto.19.25.2.atkinson.html.

Becoming Blue: A Talk with Tazewell Thompson, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wJceMuRR018.

The Glimmerglass Festival. “Blue,” September 25, 2018. https://glimmerglass.org/events/blue/.

Seattle Opera. “Blue.” Accessed November 29, 2022. https://www.seattleopera.org/blue.

Lehman, Frank Martin. “Reading Tonality Through Film: Transformational Hermeneutics and the Music of Hollywood.” Ph.D., Harvard University. Accessed November 29, 2022. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1027935855/abstract/11A66F2B62A44FA6PQ/1.

Persichetti, Vincent. Twentieth-Century Harmony: Creative Aspects and Practice. New York London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2002.

Schneller, Tom. “Modal Interchange and Semantic Resonance in Themes by John Williams.” Journal of Film Music 6, no. 1 (January 12, 2015): 49–74. https://doi.org/10.1558/jfm.v6i1.49.

Smith, Anne. The Performance of 16th-Century Music: Learning from the Theorists. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Straehley, Ian C., and Jeremy L. Loebach. “The Influence of Mode and Musical Experience on the Attribution of Emotions to Melodic Sequences.” Psychomusicology: Music, Mind, and Brain 24, no. 1 (2014): 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/pmu0000032.

Temperley, David, and Daphne Tan. “Emotional Connotations of Diatonic Modes.” Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal 30, no. 3 (2013): 237–57. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2012.30.3.237.

Tesori, Jeanine, and Tazewell Thompson. “Blue.” New York, NY: G. Schirmer, 2019.

The Glimmerglass Festival: Blue by Jeanine Tesori and Tazewell Thompson, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FMH4imgyHVw.

Washington National Opera. Blue. CD. John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Opera House, Washington D.C., 2021.Washington Post. “Creating the Opera ‘Blue,’ about Police Violence against Young Black Men, Was Hard yet Hopeful Work.” March 11, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/music/creating-the-opera-blue-about-police-violence-against-young-black-men-was-hard-yet-hopeful-work/2020/03/10/ce83401a-5fe9-11ea-9055-5fa12981bbbf_story.html.

Notes

- Blue, a new opera by Jeanine Tesori and Tazewell Thompson, was commissioned (2016) and premiered (2019) by the Glimmerglass Festival to rave reviews. Thompson, whose past work as a playwright includes plays about African American history and a play about Black activist Ida B. Wells, was the perfect choice to pen a libretto for an opera dealing with contemporary issues of race in America (Washington Post 2020). Thompson relied on his own lived experiences as a Black man in the United States as the starting point for this work (Washington Post 2020; RunnerEye 2019).

- In this essay, I capitalize racial terms such as “Black” in accordance with scholarly practices established in Critical Race Studies and journalism.

- In an interview with Francesca Zambello, the artistic and general director of The Glimmerglass Festival, Thompson recalls how he went about writing the libretto for the opera. Thompson noted that he returned to Harlem, his birthplace, to interview residents of the area as well as numerous police officers (RunnerEye 2019). The libretto of the opera is a mix of Thompson’s own lived experiences and the extensive interviews that he conducted.

- It should be noted that this opera does not attempt to portray the events within the work as a universal narrative, and my use of “a shared Black experience” throughout the essay should not be associated with the concept of a universal Black experience. There is no singular Black experience. Instead, this opera, constructed through ethnographic interviews by the librettist, aims to explore how the tragic events portrayed in the opera affect the families involved and gives audience members a way to view the humanity of the victims by showing what their home life might have looked like (Washington Post 2020). Future work on this opera could—and should—explore its representations of Blackness on the operatic stage, perhaps placing Blue within the lineage of operas about Black experiences, but this is unfortunately beyond the scope of the current essay.

- All score examples are reproduced from the unpublished Piano Vocal Score. Perusal scores may be located on Wise Musical Classical’s website. The CD referenced throughout the publication refers to the recent 2022 Washington National Opera recording of Blue. The recording by the Washington National Opera may be found on Spotify, Apple Music, and other streaming platforms.

- It should be noted that Jeanine Tesori is a white, female composer. Her identity may initially cause audiences to be suspect of the opera’s engagement with the topics of the work; however, I would like to highlight the creative collaboration between Tesori and Thompson: they worked together to hone the libretto and to allow the composer to “celebrate what [Thompson had] written” (Seattle Opera 2022). In interviews with the Glimmerglass Festival’s creative director, Thompson and Tesori discuss their collaboration in the creative process, noting that it was Tesori’s idea to have the father be a police officer rather than a musician as originally planned. Aside from this suggestion, which Thompson accepted enthusiastically, the libretto (including the opera’s narrative and plot) was constructed by Thompson. The rest of the creative process from the refining of the score through the direction of the premiere production was a collaborative effort on the part of Tesori and Thompson. I acknowledge that Tesori’s identity may have affected how she composed the score for Blue, but I cannot speak to what extent this is the case. In a personal interview I conducted with Tesori on November 21, 2021, she discussed how she went about writing the score for Blue emphasizing that her goal was to highlight the message of Thompson’s libretto. At one point, Tesori even asked Thompson to speak through the libretto in his own voice so that she could ensure that the music matched the vocal inflections and sonic emphasis that Thompson used in his performance of the text. In their edited collection, Blackness in Opera, André et al. (2012) asks whether a white composer would be able to write an authentically Black character and whether the answer to this question is altered by their collaboration with Black musicians (4). I believe that Tesori’s collaboration with Thompson acts as a productive model that André et al. (2012) attempt to analyze.

- In this essay, I use the term narrative to reference the plot of the opera in an ad hoc way, not necessarily invoking a deeper narrative structure of the work at this time. I hope to explore this opera more closely in future work in hopes of uncovering more connections between the use of musical tonalities and the opera’s plot.

- “Blue,” Seattle Opera, https://www.seattleopera.org/blue.

- The unusual capitalization of Mother, Father, Son, etc., is due to the naming conventions of the characters within the opera. The characters are named Mother, Father, Son, etc., and thus their names in this publication will be similarly capitalized.

- The Son’s murder occurs between Acts and is not depicted in the opera.

- Several music cognition studies have set out to examine the relationship between mode and emotion. David Temperley and Daphne Tan’s 2013 study had participants rank melodies by happiness and found that apart from the Lydian mode, the happiness level increased as scale degrees were raised. This perhaps links to the middle-ground connotations expressed by Gaffurius and Finck that, while theoretically the Lydian mode should be the happiest, their study supports a reading where Lydian may represent an unreachable joy and impossible sentiment. A 2014 study by Ian Straehley and Jeremy Loebach asked participants to provide emotional terms with melodies written in various modes. Their conclusions similarly linked joy and serenity with the Lydian mode by experienced listeners; however, taking unexperienced listeners into account, they again found mixed associations with the Lydian mode.

- The explication of narrative analyses derived from the use of or reference to musical topics is demonstrated in Byron Almén’s 2008 monograph, A Theory of Musical Narrative. My approach in this paper is indebted to Almén and his discussion of narrative and music though this essay’s direct connections are limited due to scope. The musical oppositions required by Almén’s theory are also not entirely musical in my analyses. The opposition arises from the lyrical content and dramatic action of the opera and how the music used helps to signify the opposition between the lyrics and actions. Therefore, my use of narrative within this essay is less in line with Almén’s use and is mainly used to reference the opera’s plot.

- I hear this section as beginning in the key of A Major (measure 398) but ultimately modulating to E major (measure 424). My understanding of the A-major beginning is two-fold. First, the primacy of A in the bass, which alternates with E, pulls my ear into a I–V shuttle. While an alternate analysis could place this entire section in E major, thus analyzing the opening as IV–I, I cannot bring my ears to hear it in that way. Secondly, and perhaps less important, the key signature changes at measure 398, the start of this section, to A major. While I do hear the piece modulating to E major, especially at the arrival of the waltz accompaniment pattern at measure 424, I do not hear the opening as beginning off-tonic.

- The bassline outlines the tritone from \hat{1}to \sharp\hat{4}while the other voices move by semitone as if they were chromatic lower-neighbors to the surrounding D major triads. The use of the tritone in the bassline, particularly to raised \sharp\hat{4}highlights this scale degree’s use more than if an alternate bassline, such as motion to \hat{7}, were used instead. I understand the E-flat in measure 124 to be a further embellishment to the D major harmony being sustained functioning as a chromatic upper neighbor to the repeated D octaves found on each consecutive downbeat.

- This excerpt represents the final instance of Lydian within the opera. Due to the limited nature of this paper, I have omitted the discussion of other small instances of the Lydian mode. These smaller uses of the Lydian mode are recollections of the more significant cases discussed in the body of the essay.

- (RunnerEye 2019)