Stefanie Bilidas

Focal Impulse Theory: Musical Expression, Meter, and the Body (2020)by John Paul Ito contributes to studies surrounding rhythm and meter through its novel premise that meter is an experience, and the interpretation of meter reflects a musical passage’s sound and effect. To capture this interpretation of meter, Ito introduces the concept of focal impulses, which are analytical tools that mark the disbursement of energy throughout a passage. Notes that impart a sense of initiation are the focal impulses, with other notes flowing from the energy that a single focal impulse generates until the next one. Each chapter discusses how readers can mark focal impulses, beginning with metrically simple situations and building toward more complex ones, aided by a wealth of musical examples from the Western Art music canon. Although Ito offers analyses through scores marked with his own reading of where the focal impulses are located, he positions his analyses as one among many plausible readings. To show this, Ito includes contrasting interpretations of the same metrical passages, thus emphasizing the flexibility of the theory to adapt to both the repertoire of study and the goal of any given analysis and/or performance. Accompanying the score are recorded performances, some of which were organized by Ito for this book and some of which are sourced from previous recordings, to provide an aural demonstration of differing focal impulse placements. The page “Accessing Audiovisual Materials” outlines links to the websites and streaming platforms where these recordings, video, and scores are found. Ito connects the multiplicity of focal impulse interpretations to differing hermeneutic readings, pairing the placement of impulses to shifts in narrative outlooks, such as tying together less frequent impulses per measure with a tragic narrative. Focal Impulse Theory brings together theoretical meter analysis with performance analysis and narrative studies, guiding readers on how to decide where the energy in pieces should lie and, in doing so, what narrative implications they may be giving to the music.

Summary

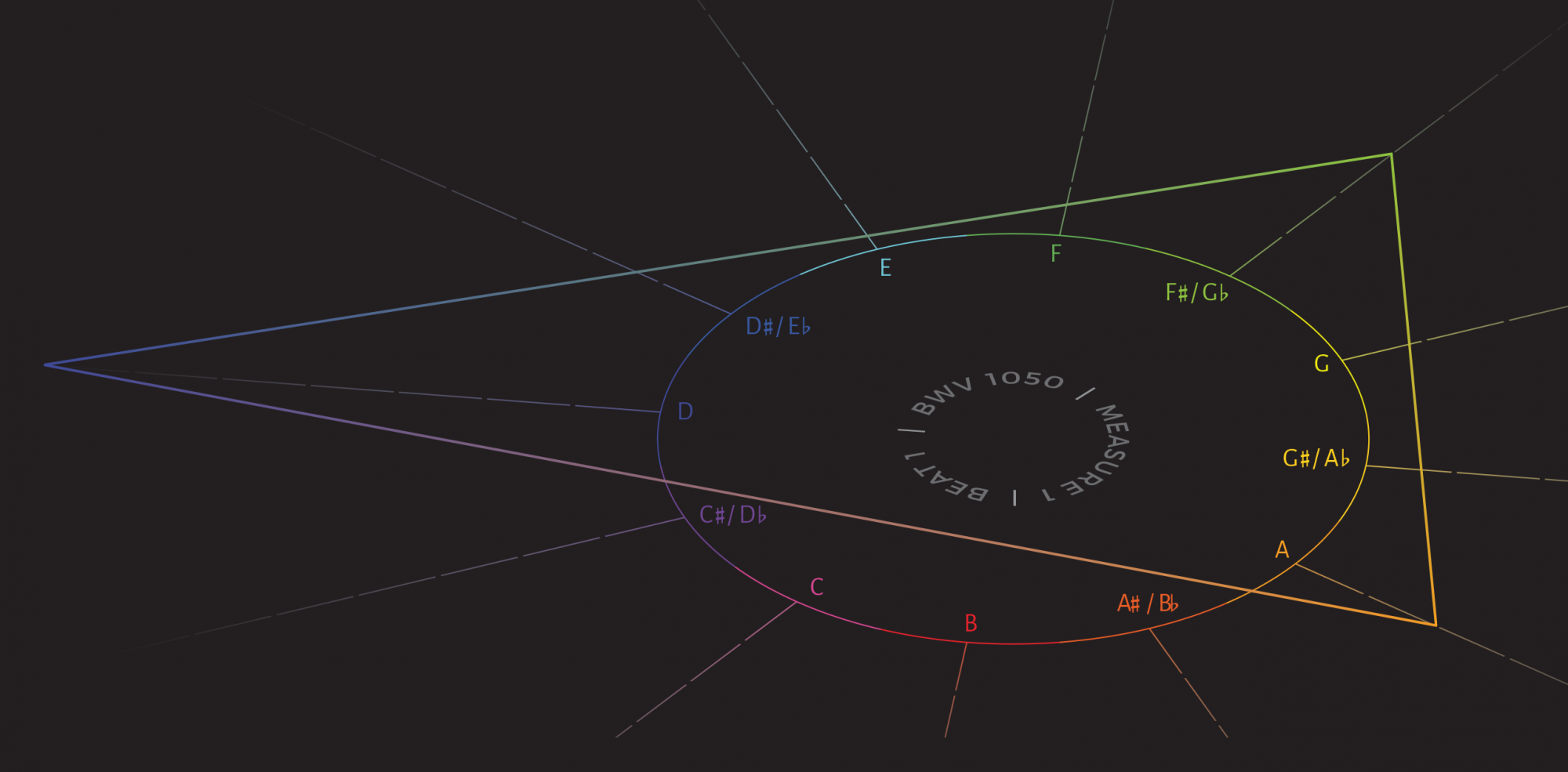

Chapter 1 begins by questioning what it means to experience meter and, in doing so, interrogates how one’s perception of meter affects the resulting performance of a musical passage. He argues that by placing emphasis on different beats and at differing levels of metrical organization, musicians open up new hermeneutic interpretations that result in varying aural and kinesthetic experiences of the music. Focal impulses rely on the hierarchical conception of meter, building on the work of Lerdahl and Jackendoff (1983), discussed in Chapter 2. With the metrical grid intact, focal impulses comment upon it, showing places of emphasis. However, Ito notes that focal impulses have their own internal hierarchy, with primary focal impulses governing over secondary and subsidiary impulses, and secondary ones over subsidiary impulses. All analyses in the book are given focal impulses above the staves, but several also have hypermetrical indications, such as 1/4 and 4/4. The second number refers to the length of the hypermeasure in measure units. The first refers to its hypermetrical weight in the unit, using his own previous contribution (2013) of beginning- and end-weighted hypermetrical groupings. Hypermeter plays a role in determining the feeling of the phrases but does not affect the placement of focal impulses.

In Chapters 3–6, Ito lays the groundwork for focal impulse theory, outlining its basic principles. For clarity, all terms associated with the theory are in italics from this point forward. Focal impulses initiate movement and propel the music forward. Although music happens in the space between impulses, which Ito defines as consequent spans, these subsidiary impulses are only a reaction to the movement caused by the focal impulse. The general principle is that focal impulses occur at the measure level, half-measure level, or up to two levels lower than the measure level and remain consistent throughout a formal section, such as a phrase or first theme of a sonata exposition. For example, in 4/4, pulses might occur at the whole note, half note, or quarter note level. In 6/8, pulses might be at the dotted-half-note, dotted-quarter-note, and eighth-note levels. In both cases, the pulses are evenly spread out in the measure. The pattern departs with $3/4, with Ito’s view that its metrical emphasis is almost always displayed as an unequal duple meter, with the secondary focus on beat 2 or 3, resulting in a longer beat 1 or beat 2. Therefore, focal impulses may be placed unevenly throughout the meter. With all metrical contexts, pulse placement is passage-specific and should be consistent throughout a passage. Ito provides a chart of focal impulse schemas for simple meters and 6/8, which acts as a reference as readers move further into the book (80). Throughout these analytical discussions, Ito intersperses musical examples with references to specific performances that demonstrate different possible focal impulse placements of the same passage and the contrasting hermeneutic readings and emotional characters that result from the performers’ choices.

Having started with cases where the focal impulses and metrical grid align, in Chapters 7 through 9 Ito moves towards more complex techniques where the audible accents are detached from the meter, such as with syncopation. Ito defines syncopation through its interactions with focal impulses that lie on the meter and the emotional quality these decisions impart. Forming the strongest pulses, vigorous syncopations are planted between focal impulses and receive accentuation that suggests a rivaling of emphasis. Grounded syncopations share a focal impulse and therefore sound placed into the meter, while floating syncopations have two attacks per focal impulse, giving them a lighter feel. Extending his discussion to hemiolas, Ito generally argues that in order to experience the metrical conflict between the heard and notated meters, performers should use focal impulses to bring out the notated meter—but in keeping with the theme of this book, this is only one possible interpretation. In cases where there is a prolonged conflict between the notated meter and heard meter or persistent syncopation in addition to hemiolas, impulses could be shifted to fit the onset of hemiola events. In this case, Ito introduces the concept of anticipated focal impulses, where the onset of the focal impulse occurs with a strong attack on an offbeat, but its energy is sustained into the notated downbeat. As Ito’s theory stems from written score-based music, where performers learn the music in the context of a set metrical schema, it therefore makes sense that Ito prioritizes the notated meter when both analysts and performers are visually presented with the metrical conflict. It would be interesting to see the applicability of this position to music that is non-notated and relies upon a listening-based analytical experience.

In the middle section of the book, Ito employs two techniques for focal impulses that nuance the way that they are deployed in analyses and performance. The first is impulse polyphony, discussed in Chapter 8, where not all focal impulses must align. Impulse polyphony is often created when two or more textural layers have different surface rhythms, resulting in the need for separate focal impulses. Often, the impulses are split between one layer with an active surface rhythm and another with a slower melodic line. With the technique of impulse polyphony, performers can analyze their own parts separate from others in their ensemble. Ito departs from scholarship on multiple agencies where each player operates as an individual agent (Cone 1974; Monahan 2013; Klorman 2016; Hatten 2018). Instead, Ito chooses to examine the analyst as an authority figure in a position of higher agency, who is able to acknowledge both layers of metrical coordination played by multiple individuals and view the ensemble texture as a composite entity, a position in line with Justin London’s (2012) views of metrical dissonance. Impulse polyphony increases the range and applicability of focal impulses through its specificity, allowing theorists and performers to adjust focal impulses to the specifics of each metrical layer, including marking hemiolas, syncopations, and changes in meter where it is observed in parts of the texture, but not in full.

A pivotal moment is the introduction of inflected impulses in Chapter 10. Until this point, every primary focal impulse has served the same purpose—to initiate energy that is sustained until the next impulse. The introduction of inflections splits this energy into two categories: releasing tension and gathering tension. Impulses that release tension are called downward impulses, and impulses that gather tension are called upward impulses. Together, they make a complete binary cycle. Not every cycle, however, is a binary one. As Ito explains, the impulses may have a dual function of releasing and gathering tension all in one—a unitary impulse cycle. Unitary cycles may begin with the releasing or the gathering of tension, the subject of chapters 11 and 12. Ito encourages readers to conduct and envision the feeling of the inflected impulses, using the metaphor of motion to communicate the affective power of inflected impulses.

Chapters 13 and 14 serve as additional literature reviews, connecting Ito’s theory to various adjacent subdisciplines of music theory and other fields. The sheer wealth of literature is commendable and highlights both the backing of focal impulse theory in current literature and possible future applications. Chapter 13 discusses psychology studies, from music cognition (Sloboda 1983, 1985; London 2012; Manning and Schutz 2013, 2015), movement (Toiviainen, Luck, and Thompson 2006; Schaal et al. 2004; Park et al. 2007), and speech (Cummins and Port 1998; Rusiewicz 2011), that inform Ito’s approach to focal impulse theory. While he intends for focal impulses to be perceptible, he questions the literal nature of focal impulses and suggests that they may be metaphorical, due to the speed of focal impulses. At slower tempos, focal impulses are further apart and may be outside of the limits of human perception. Ito draws on studies by Repp (2006b), Parncutt (1994), and London (2012) to make this claim. At the time of publication, Ito suggests that experimental studies could work to articulate where the theory moves from literal to metaphorical. Even with its status as metaphorical, focal impulses are useful for performers, helping them coordinate both their physical motion and the hermeneutic reading of musical passages. Since focal impulses have an element of motion and physicality, both in how the music implies places of movement and how performers execute those passages when the music is realized, Ito spends Chapter 14 establishing connections with embodiment, gesture, and phenomenology. Since theorists and listeners are not articulating movement that makes the sounds of the score a reality, they rely on embodiment mirroring to some extent the performer’s actions (Cox 2011). While embodiment studies begin first with physical gestures (Jaques-Dalcroze 1916; Whiteside 1997; Pierce 2007; De Souza 2017), a study of focal impulses first begins from analytical reflections before moving into performance. Chapter 14 also contextualizes Christopher Hasty’s theory of metrical projection (1997) with focal impulse theory. Shared by the two authors is meter as an experience where beginnings are crucial to the ways in which participants interpret the resulting music. Ito, however, characterizes Hasty’s focus as one interested in the possibilities of meter and the confirmation of expectations people have. Viewing focal impulses as dynamic events that set off motion, Ito considers focal impulses to be active and much less speculative.

Ito spends the final two chapters, 15 and 16, tying together the various concepts explored throughout the book, using examples by Brahms. Readers may want to glance ahead at this chapter to get a sense of the book’s trajectory prior to learning all of the terminology associated with the theory. Chapter 15 features small-scale examples, while Chapter 16 is dedicated to whole pieces—the first movements of Brahms’s Sonata for Clarinet op. 120 nos. 1 and 2. Ito analyzes the metrical trajectory of each movement through focal impulses and a hermeneutic reading. The metrical complexity of both movements allows Ito to showcase many of the concepts discussed in the book simultaneously. Not only does Ito provide full analyses in the supplemental materials, but he also includes his performances of the works with pianist David Keep. In using his first-person perspective to note how the rehearsal process impacted the final determination of focal impulses for the movement, Ito demonstrates the core aspects of the book—that focal impulses are about initiating movement and the experience of meter.

Ito’s analysis of the first movement of Op. 120 no. 1 (308-322) stands out for his ability to weave together the metrical conflict of sonata form with a narrative of a doomed subject who is unable to overcome the turbulence of metrical conflict. As the sonata exposition unfolds, the piano and viola’s pairing unravels and the metrical complexity includes syncopation, hemiola, changing meters, and impulse polyphony between the two instruments. Drawing together these metrical events, Ito proposes a reading of the exposition where a fictional subject cannot find his metaphorical footing, leading to thoughts of despair. While there are moments of repose, such as the closing theme and start of the recapitulation, the sonata, bound by its genre, treads the same tragic narrative path. The piece ends with a final restatement of the primary theme with its calm metrical stability, but Ito offers the damning statement that there is no positive outlook for the subject, only that “the biting edge of desperation has been taken away” (322). Chapter 16 demonstrates the culmination of focal impulse theory, showing its applicability to many situations of metrical dissonance and the narrative implications that come with centering metrical analysis.

Reflections

Ito primarily targets his work at two contrasting audiences, music theorists and performing musicians, but a strength of his contribution is his ability to weave analytical ideas and their practical applications into most chapters. For music theorists, the theory of focal impulses has an expansive scholarly reach, connecting with adjacent subfields of performance and analysis, music cognition, embodiment, and phenomenology. For performers, Ito demonstrates the applicability of his theory to practice through myriad examples and accompanying performances. Ito’s commitment to “minimize jargon and to make the discussion as readable as possible” (23) results in prose that is accessible to non-academic readers. Furthermore, the modular format allows audiences to find places of relevancy to their discipline. There are chapters that explain the theory’s working (Chapters 2–5, 7–12), ones dedicated to musical analyses (Chapters 15 and 16), and ones that connect focal impulses to existing scholarship (Chapters 6, 13, and 14). Ito intends that the differing audiences will be drawn to different chapters and notes that “the performer may wish to skip chapter 6…and chapters 13 and 14” (23), alleviating a sense that the book should be read cover to cover. The unique format of the book consequently means that all the information about the theory’s working unfolds over the course of several chapters, instead of being concentrated in one or two chapters found at the beginning. The full piece analyses offered in Chapter 16 tie together multiple metrical techniques explored earlier in the book with hermeneutic readings, demonstrating an integrative analytical approach that is useful for both theorists and performers alike.

Ito sets boundaries for the repertoire that is examined throughout the book that is informed by his ability to contribute not only as an analyst, but as a conductor, singer, and ensemble performer. He states in the introduction that “focal impulses…commonly align with some level of meter, especially in the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Western classical music that is the primary focus on this book” (4). Since Ito is a violist, the repertoire is primarily chamber music or solo string works, but there are some examples of lieder, keyboard, wind pieces, and large ensemble works. There are also examples from the Baroque period and the twentieth century. The first-person perspective that Ito provides is commendable and shows a rich integration between the theorical and practical traditions. The theory is based around this repertoire and on the assumption that players and analysts have access to a score, where the metrical context is determined by set meters and rhythmic values. Most prominently, Ito’s interpretations of metrical complexity rely on the choice of a performer to either maintain and accent a written meter or shift to the meter suggested by accentuation patterns. The influence of the score as a starting point for both analysis and performance works for both the repertoire studied and the supporting performing practice, where coordination between players is valued. The theory’s application is then stretched when applied to music that does not cultivate a reliance to a written score and/or a hierarchical ensemble model where ensemble coordination is a prized aesthetic.

Ito acknowledges that “regularly periodicity is central to the use of focal impulses in the repertoire discussed in this book, but it is not central to what a focal impulse is” (335). With focal impulses being the impetus for motion, Ito acknowledges that motion could be placed at regular or irregular intervals. For an extension of the theory using non-notated music that involves regular periodicity, Ito suggests looking at electronic dance music where physical motion helps confirm participants’ entrainment to the groove (340). With music that eschews metrical regularity, focal impulse theory may be less useful, although one can see how Ito’s concept of placing focal impulses before the start of music after long pauses could serve to coordinate players performing music that is not periodic.

Lastly, the repertoire featured in the book is primarily by canonic composers, who are white and male. A welcome addition to the book is the performances and recordings that Ito mentions or supplies. The performers are more diverse, particularly in newer recordings that were tailored to be in the supplementary materials or those sourced from the past 40 years. The recordings show how focal impulse theory can be applicable to a wide range of performers that play music drawn broadly from the Classical music tradition. As an analytical theory, especially for score-based Western Art music, Ito’s approach has much to offer, and I would appreciate contributions by future scholars that use the theoretical framework of focal impulse theory to discuss works by non-canonic composers.

Ito’s core premise is that music has moments of energy, and focal impulse theory can equip analysts and performers to find those moments in music that are metrically complex and provide insight on how to interpret them in performance. The fluidity of the theory allows it to successfully account for many equally valid interpretations and confirms that there is analytical value in following the process of exploring possible options. Ito concludes by offering some further areas for the application of focal impulse theory, such as dance studies and repertoires of non-Western musics and popular music. However, he notes that applications outside of Western Art music may be limited and scholars should consider what tenets of the theory can be applied to these repertoires. While Focal Impulse Theory primarily introduces the theory of focal impulses and serves as a guide on how to apply them for analytical purposes, Ito’s commitment to performance saturates the approach, and thus at the heart of the volume lies the theory’s practical application for performers and its grounding in lived experiences.

References

Cone, Edward T. 1974. The Composer’s Voice. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Cox, Arnie. 2011. “Embodying Music: Principles of the Mimetic Hypothesis.” Music Theory Online 17 (2). https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.11.17.2/mto.11.17.2.cox.html.

Cummins, Fred and Robert F. Port. 1998. “Rhythmic Constraints on Stress Timing in English.” Journal of Phonetics 26 (2): 145–71.

De Souza, Jonathan. 2017. Music at Hand: Instruments, Bodies, and Cognition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hasty, Christopher F. 1997. Meter as Rhythm. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hatten, Robert S. 2018. A Theory of Virtual Agency for Western Art Music. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Ito, John Paul. 2013a. “Hypermetrical Schemas, Metrical Organization, and Cognitive-Linguistic Paradigms.” Journal of Music Theory 57 (1): 47–85.

Jaques-Dalcroze, Emile. 1916. La Rythmique : Enseignement Pour Le Développement de l’Instinct Rythmique Et Métrique, Du Sens de l’Harmonie Plastique Et de l’Equilibre Des Mouvements, Et Pour La Régularisation Des Habitudes Motrices, vol. 1. Lausanne: Jobin.

Klorman, Edward. 2016. Mozart’s Music of Friends: Social Interplay in the Chamber Works. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lerdahl, Fred and Ray Jackendoff. 1983. A Generative Theory of Tonal Music. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

London, Justin. 2012. Hearing in Time: Psychological Aspects of Musical Meter. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Manning, Fiona C., Jennifer Harris, and Michael Schutz. 2013. “Moving to the Beat’ Improves Timing Perception.” Psychonomic Bulletin and Review 20 (6): 1133–39.

———. 2015. “Movement Enhances Perceived Timing in the Absence of Auditory Feedback.” Timing and Time Perception 3 (1 – 2): 1–10.

Monahan, Seth. 2013. “Action and Agency Revisited.” Journal of Music Theory 57 (2): 321–71.

Park, Se-Woong, Hamal Marino, Steven K. Charles, Dagmar Sternad, and Neville Hogan. 2017. “Moving Slowly is Hard for Humans: Limitations of Dynamic Primitives.” Journal of Neurophysiology 118 (1): 69–83.

Parncutt. Richard. 1994. “A Perceptual Model of Pulse Salience and Metrical Accent in Musical Rhythms.” Music Perception 11 (4): 409–64.

Pierce, Alexandra. 2007. Deepening Musical Performance through Movement: The Theory and Practice of Embodied Interpretation. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Repp, Bruno H. 2006b. “Rate Limits of Sensorimotor Synchronization.” Advances in Cognitive Psychology 2 (2): 163–81.

Rusiewicz, Heather L. 2011. “Synchronization of Speech and Gesture: A Dynamic Systems Perspective.” In Proceedings from the 2nd Gesture and Speech in Interactions Conference, Bielefled, Germany. http://gespin.amu.edu.pl/?page_id=46.

Schaal, Stefan, Dagmar Sternad, Reiko Osu, and Mitsuo Kawato. 2004. “Rhythmic Arm Movement Is Not Discrete.” Nature Neuroscience 7 (10): 1136–43.

Sloboda, John A. 1983. “The Communication of Musical Metre in Piano Performance.” Quarterly Jounral of Experimental Psychology 35A (2): 377–96.

———. 1985. “Expressive Skill in Two Pianists: Metrical Communication in Real and Simulated Performances.” Canadian Journal of Psychology 39 (2): 273–93.

Toivianinen, Petri, Geoff Luck, and Marc R. Thompson. 2010. “Embodied Meter: Hierarchical Eigenmodes in Music-Induced Movement.” Music Perception 28, (1): 59–70. Whiteside, Abby. 1997. Indispensables of Piano Playing. In Abby Whiteside on piano Playing: Indispensables of Piano Playing & Mastering the Chopin Etudes and Other Essays, edited by Joseph Prostakoff and Sophia Rosoff. Portland, OR: Amadeus.