Kyle Hutchinson

Abstract

This article proposes that motivic Black vernacular musical topics, which typically coalesce at the musical surface, can also serve as progenitors for deeper-level tonal structure. Building on the work of Rae Linda Brown, Horace Maxile Jr., and Samuel Floyd Jr., I demonstrate this approach through an analysis of the second movement of Florence Price’s Piano Sonata in E minor (1932). My analysis highlights pitch relationships— particularly motivic pendular thirds, a Black topic which Maxile Jr. (2022) describes as two pitches that “pivot around a central pitch (most likely a tonic), the third above the central pitch being major or minor, the third below minor”—and ways in which deeper-level structures develop from these surface-level pendular motifs. The second part of the article then frames my analysis through Price’s heritage as a woman of mixed racial background, and her experiences as a Black composer in the twentieth century.

View PDF

Return to Volume 36

Keywords and Phrases: Florence Price; Black Topics; Pendular Thirds; Tonal Structure; Motivic Enlargement

Introduction

As Horace J. Maxile Jr. describes, despite “the volume and strength of the recent work in black music scholarship, much work is still needed in many areas, particularly those of scholarly criticism, interpretation, and analysis of concert works by black composers” (2008, 123). More specifically, Maxile Jr. proposes that intimate and detailed attention to considerations of “pitch, harmony, rhythm, and form will enlighten our interpretations of works by black composers and fortify the course of black music scholarship” (2008, 123). Following the work of V. Kofi Agawu (1991), Maxile Jr. approaches these issues through a lens of what he terms vernacular African American topics, or emblems, the interactions of which he describes as “creat[ing] the most powerfully expressive utterances in African American music, especially when realized in a ‘classical’ setting” (2008, 127).1 As Maxile Jr. himself notes, musical emblems are often oriented toward the musical surface, though in more recent work he has also developed approaches that treat these emblems as “signifiers that can affect a work’s formal and expressive trajectories” (2022, 141).

Using the second movement of Florence Price’s Piano Sonata in E minor as a case study, this article develops Maxile Jr.’s asseverations.2 More specifically, I theorize that beyond existing as “effective surface-level subtleties” (Maxile Jr. 2022, 141) or formal-structural signposts, black vernacular musical emblems can serve as progenitors for musical structure, germinating from the motivic surface of the music to find enlarged expression in both harmonic relationships and tonal structure.3 Indeed, Maxile Jr. describes Price as “highly successful in incorporat[ing] Black folk elements” into the more classical structures of her music (2022, 139), noting how these “two musical impulses, the Black folk and the neo-Romantic, often blend in compelling ways, resulting in rich expressions of [Price’s] culture and heritage while also demonstrating consummate craftmanship” (2022, 139). In an analysis of the first movement of this sonata, Maxile Jr. describes how Black emblems “function both affectively and structurally” (2022, 140), suggesting that in Price’s music it is not simply a case of importing surface-level Black vernacular elements into a more Western classical formal structure, but rather that the vernacular elements merge, fuse, and blend with Western vernacular elements.

While this movement espouses a variety of black musical emblems in the rhythmic, formal, and pitch domains, this article focuses on those expressed primarily through pitch relationships. In particular, my analysis highlights the presence of motivic pendular thirds, a type of relationship wherein two pitches “pivot around a central pitch (most likely a tonic), the third above the central pitch being major or minor, the third below minor” (Maxile Jr. 2022, 141), and ways in which deeper-level harmonic and tonal relationships develop from these surface-level pendular motifs.4 By examining voice-leading, harmonic, and linear structures as they relate to $$\hat6$$, $$\hat1$$, and $$\hat3$$ in a pendular relationship—first at the motivic foreground and then at deeper levels of structure through the process of enlargement—I contend that Price’s use of black idioms and topics extends beyond the musical surface to permeate the structural hierarchies of the music, creating an effective fusion of black musical emblems with a more classical musical structure. Following the more congeneric analysis in the first part, the second part of this article directs that analysis to a brief extrageneric interpretation, framing my analysis through Price’s heritage as a woman of mixed racial background, and her experiences as a Black composer in the twentieth century.5

1. Analysis

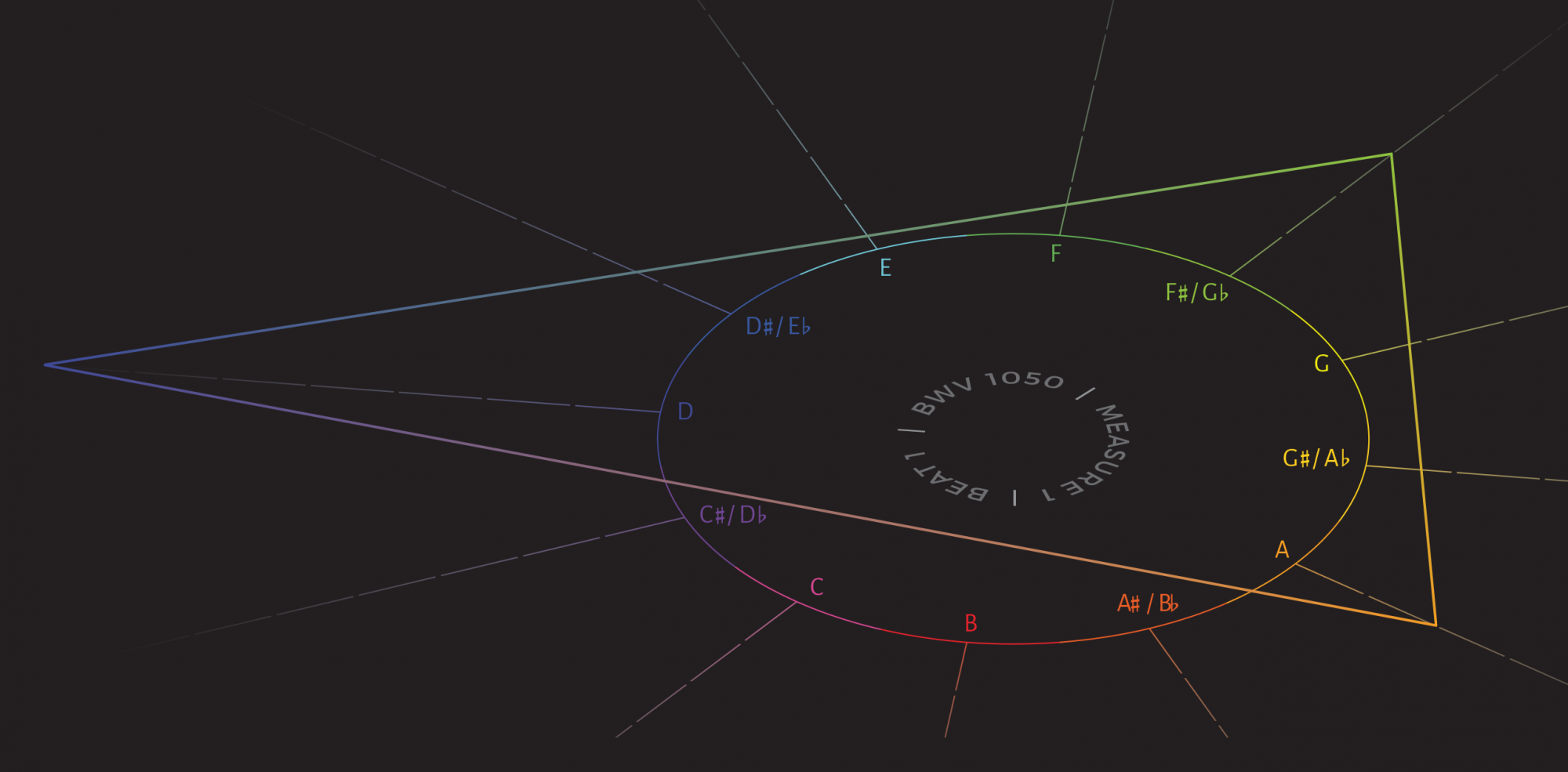

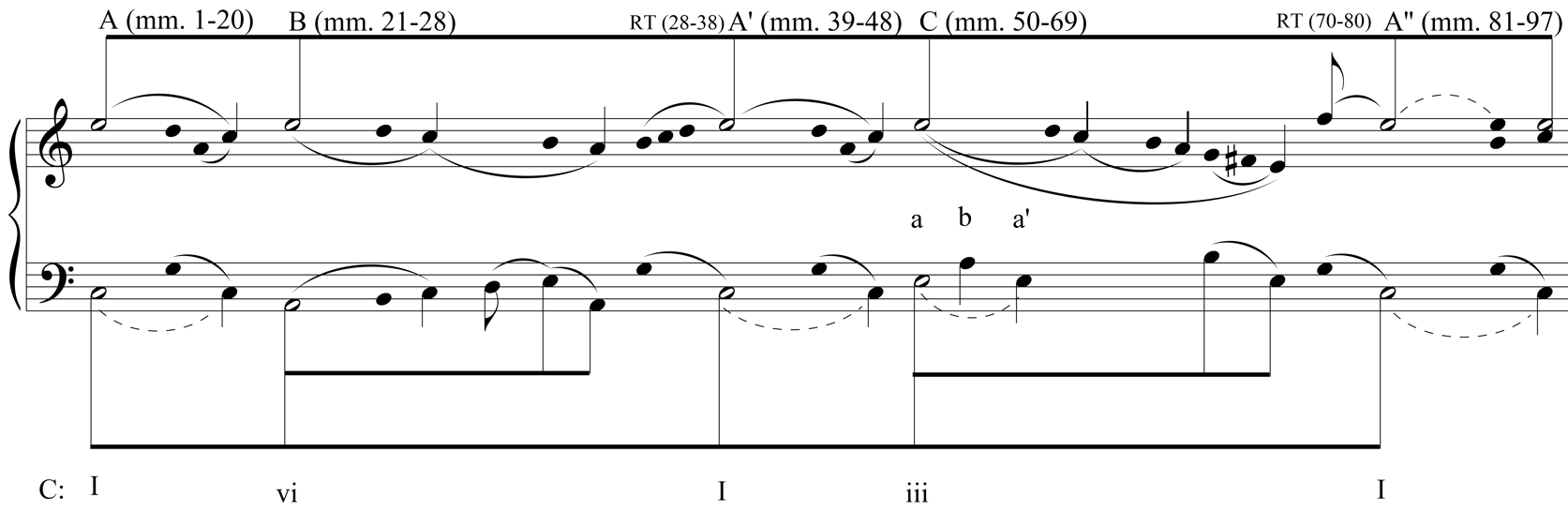

As Rae Linda Brown describes, Price’s Piano Sonata in E minor is “a large-scale, expansive work in the Romantic tradition,” with a second movement cast as “a rondo [that] begins with a lyrical tune reminiscent of the spiritual[,] treated with characteristic syncopated rhythms and simple harmony,” but that also foregrounds Price’s love of Romantic music, with “two secondary themes [that] are reminiscent of Chopin and Schumann respectively” (2020, 146).6 The chart in Table 1 provides a schematic overview of the tonal and formal structure of this movement to quickly orient the reader to the large-scale formal sections and tonal areas. In his monograph The Power of Black Music, Samuel A. Floyd Jr. describes the rondo structure as “the standard for marches and classic ragtime pieces,” and suggests that it “was familiar to black folk musicians in the late nineteenth century, since similar configurations have been found to be typical of African-American folk rags” (1995, 69). Notably, however, Floyd Jr. suggests that the key structure for folk rags was oriented around tonic, dominant, and subdominant key areas, much like the rondos of the European common practice. Thus, the key areas for this movement are not what we might term “first-level defaults” (after Hepokoski and Darcy 2006) for a common-practice rondo, nor for a typical folk rag.

| Section | Measures | Key | Formal Design |

| A(Spiritual) | 1–20 | C Major | Sentential (mm. 1–4) with two repetitions exhibiting increasing chromatic elaboration (mm. 5–20) |

| B(Chopin) | 21–28 | A minor (vi) | Period |

| Retransition(Dissolving Consequent) | 28–38 | 🡪 V/C | |

| A’ | 39–49 | C major | Sentential |

| C(Schumann) | 50–69 | E minor (iii) | Small Ternary |

| Retransition | 70–80 | 🡪 V/C | |

| A” | 81–89 | C major | Sentential |

| Coda | 90–102 | C major |

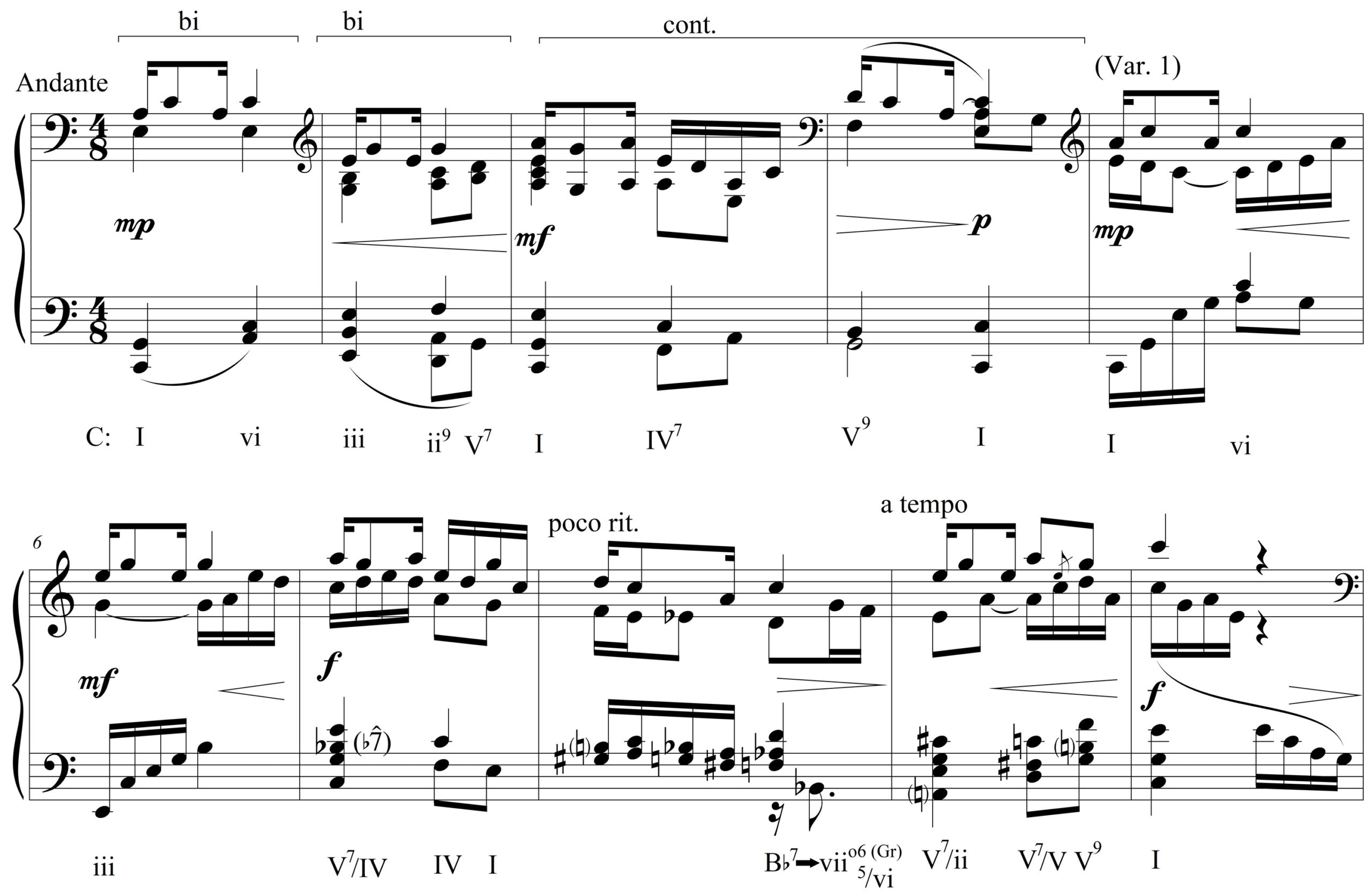

The A section, described by Brown as reminiscent of a spiritual, consists of a repeated pentatonic theme shown in Example 1a. The rhythmic profile of this theme, with its syncopated eighth-sixteenth-eighth motif is emblematic of black folk rhythms: as Floyd Jr. describes, “The typical African-derived rhythms  , and

, and  …were patterned variously to diverse songs, games, and dances…and had a strong influence on the folk rag” (1995, 54–55).7 In its first iteration the theme is harmonized with a relatively simple and entirely diatonic accompaniment, but in its repetitions (mm. 5–10, and 11–20) the accompaniment involves increasing chromatic elaboration with a particular emphasis on the subtonic tone, B$$\flat$$, and other modal “blue” notes, which Maxile Jr. likewise describes as African American vernacular musical emblems (2022, 141).8 This emphasis can be seen in the first variation shown in Example 1a, where B$$\flat$$ is appended to the tonic in a tonicization of the subdominant. B$$\flat$$ then forms the bass tone of an apparent B$$\flat$$7 harmony that averts the cadence in m. 8, and then resolves as an applied German vii$$^{\circ}$$$$^{6}_{5}$$ of the submediant, launching a string of applied dominants in a “one more time” effect (after Schmalfeldt 1992) that leads to the cadence.9

…were patterned variously to diverse songs, games, and dances…and had a strong influence on the folk rag” (1995, 54–55).7 In its first iteration the theme is harmonized with a relatively simple and entirely diatonic accompaniment, but in its repetitions (mm. 5–10, and 11–20) the accompaniment involves increasing chromatic elaboration with a particular emphasis on the subtonic tone, B$$\flat$$, and other modal “blue” notes, which Maxile Jr. likewise describes as African American vernacular musical emblems (2022, 141).8 This emphasis can be seen in the first variation shown in Example 1a, where B$$\flat$$ is appended to the tonic in a tonicization of the subdominant. B$$\flat$$ then forms the bass tone of an apparent B$$\flat$$7 harmony that averts the cadence in m. 8, and then resolves as an applied German vii$$^{\circ}$$$$^{6}_{5}$$ of the submediant, launching a string of applied dominants in a “one more time” effect (after Schmalfeldt 1992) that leads to the cadence.9

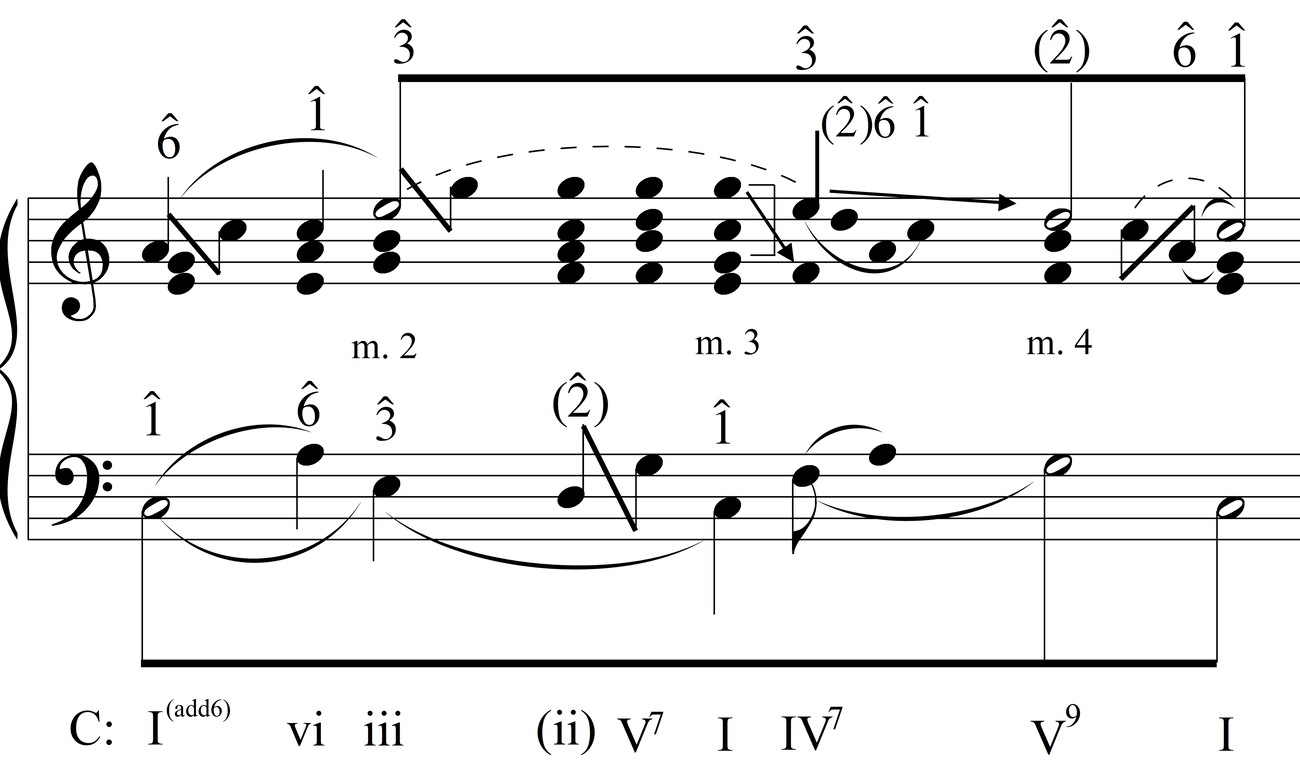

The theme immediately draws attention to $$\hat6$$ by means of an initial tonic triad with an additional sixth, A, in the melody. As shown in Example 1b, rather than serving as a dissonant, and thus subordinate, embellishment to $$\hat5$$, the sixth skips up to $$\hat1$$ as part of an initial $$\hat6$$–$$\hat1$$–$$\hat3$$ arpeggiation,10 a melodic freedom that characterizes the opening sonority as I(add6), a way of hearing which David J. Heyer describes as “[setting] jazz and common-practice harmony apart on the surface” (2012, 2.2) because of the way in which it treats $$\hat6$$ as hierarchically equivalent to $$\hat5$$.11 As the primary melodic motif, the $$\hat6$$–$$\hat1$$–$$\hat3$$ arpeggiation instills an initial sense of thirds in a pendular relationship above and below the tonic, with the relationship between the lower third, $$\hat6$$, and $$\hat1$$ being especially prominent on the musical surface. As Jeremy Day-O’Connell describes, the $$\hat6$$–$$\hat1$$ melodic figure that opens the movement—which he notes is prominent in Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag”—“can be seen as having integrated vernacular ‘African retentions’” (2002, 55).12 And while the emphasis on these pitches related in thirds might be seen as a product of pentatonicism, their emphasis also creates an aesthetic that is somewhat distinct from the ways in which European composers tended to treat the pentatonic collection. Boyd Pomeroy, for instance, describes how the “true nature” of pentatonic collections in common-practice tonality “resides in the decorative embellishment of the tonic triad’” (Pomeroy 2003, 159; see also Day-O’Connell 2009, 234). It is not, however, the tonic triad that is elaborated in this opening theme, but rather the $$\hat6$$–$$\hat1$$–$$\hat3$$ motif because of the ways in which $$\hat6$$ asserts its own melodic independence from $$\hat5$$.13

The pendular disposition of thirds around the tonic shifts in the second measure: here, the oscillation between $$\hat3$$ and $$\hat5$$, combined with the more functional harmonic progression, induces a more diatonically, rather than pentatonically, oriented syntax.14 This sense of diatonicism is further reinforced at the downbeat of m. 3, where the return of the I(add6) chord now sees $$\hat6$$ functioning in common-practice terms as an embellishment to $$\hat5$$. The continuation phrase that follows (mm. 3–4) then reverts to a pendular/pentatonic disposition: the syncopated rhythm does not linger on $$\hat5$$ but returns to $$\hat6$$, which then assumes a more pendular role in conjunction with $$\hat3$$, as both scale degrees remain oriented around, and drawn to, the tonic. As shown in Example 1b, in m. 3 $$\hat3$$ passes through $$\hat2$$ on the way to $$\hat1$$, while $$\hat6$$ skips up directly to $$\hat1$$. This shift back to this more pendular orientation around $$\hat1$$ remains in effect until the final gesture, which sees the A skip up a third to C—though it does so while also being held over and resolving down to G, simultaneously reflecting the pendular and functional behaviors of $$\hat6$$.15

The melodic character of the theme might thus be seen to fuse elements of both Black musical idioms and common-practice diatonic tonality. The pendular thirds that begin the theme give way to a more diatonically oriented repetition of the basic idea, which then fuses back again into a melody characterized by the pendular thirds. Samantha Ege describes this as “musical code switching” (2020a, 95–97), and notes that while Price “code-switches with ease into the Romantic languages of Chopin and Schumann,” in this movement “intra-sectional approaches to code switching abide within the refrains themselves and not just the linear approaches between sections” (2020a, 97).16

While the pendular thirds are a prominent melodic motif, even more striking is that their disposition is not restricted to the musical surface; as shown in Example 1b, $$\hat6$$, $$\hat1$$, and $$\hat3$$ are also prominent harmonic, as well as melodic-structural, motifs, imparting a sense that the initial motivic profile is undergoing enlargement. For instance, the harmonic-prolongational profile of the presentation phrase is characterized by pendular third-relations: the opening three harmonies have roots of C ($$\hat1$$), A ($$\hat6$$), and E ($$\hat3$$) respectively, with $$\hat6$$ arising from $$\hat1$$, and $$\hat3$$ then passing through $$\hat2$$ on its way back down to $$\hat1$$. Both bass pitches are, in effect, derived from and drawn back toward the tonic through the process of prolonging it. These same pendular thirds also find enlarged expression in the melody of the continuation. The structural E—itself prolonged by the surface-level ($$\hat2$$)–$$\hat6$$–$$\hat1$$ described previously—passes through D in m. 4 on its way to the final tonic, but the final melodic tonic is prefaced with the A below it. The pendular thirds that form the melodic motif of the theme thus serve as a sort of germinating idea that spreads across various levels of melodic and harmonic structure: in this theme, but throughout the remaining sections as well.

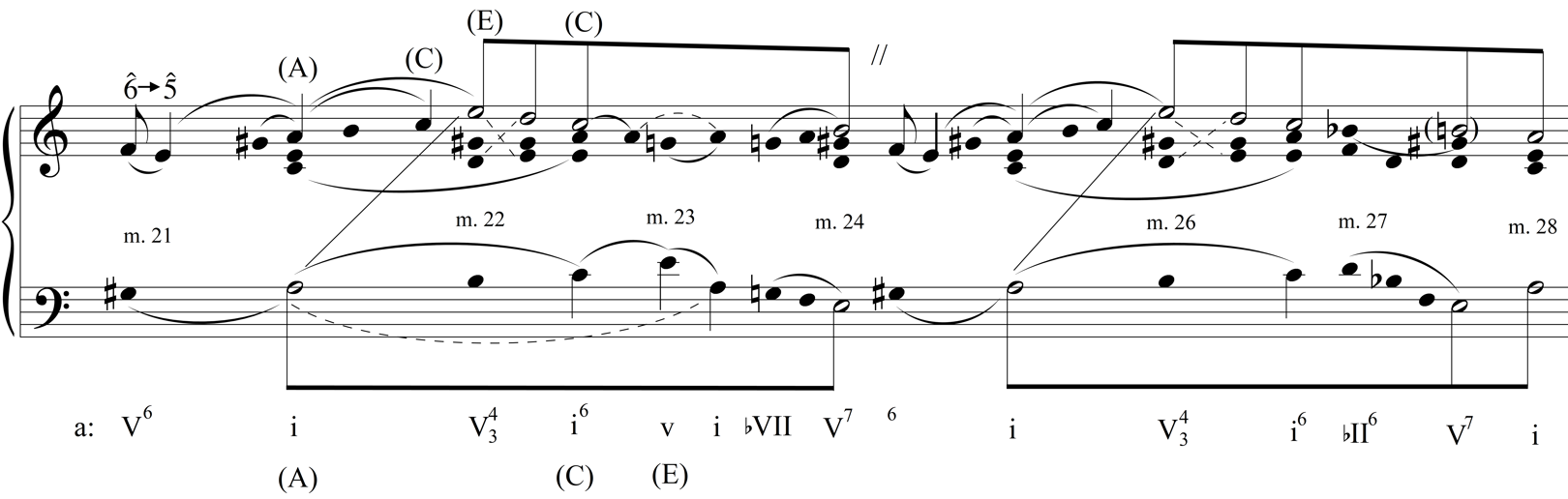

Cast as a relatively typical period, the B section, shown in Example 2a, rescinds the pentatonic melody of the A section, opting instead for a melody firmly rooted in the A-minor diatonic scale.17 This melody, however, maintains a link to the A section by emphasizing the same three pitches, A–C–E, even as it casts them in a new tonal context. The two-measure basic idea (mm. 21–22) begins with $$\hat6$$ (F$$\natural$$) of the local A-minor tonic serving as an accented appoggiatura to $$\hat5$$ in the initial V6 chord, rather than existing on an equal hierarchic footing with $$\hat5$$ as it did in the A section. An arpeggiation of the A–C–E motif leads to the primary melodic tone E in m. 22, which then descends through D to C. A skip down a third introduces the tonic pitch below C, which I read as a motion to an inner voice. This inner-voice A is prolonged by the minor-flavored dominant that follows in the two-measure contrasting idea (mm. 23–24) before converging with the structural upper voice on $$\hat2$$ at the half cadence. A similar structure follows in the consequent, save that the minor dominant of the contrasting idea is replaced with a predominant-functioning Phrygian $$\flat$$II6. While the basic idea of this theme retains emphasis on the same three motivic pitches, the shift to A minor reframes the pitches as $$\hat1$$, $$\hat3$$, and $$\hat5$$, which in tandem with the more scalar nature of the section, mitigates the pendular relationship they exhibited in the A section.

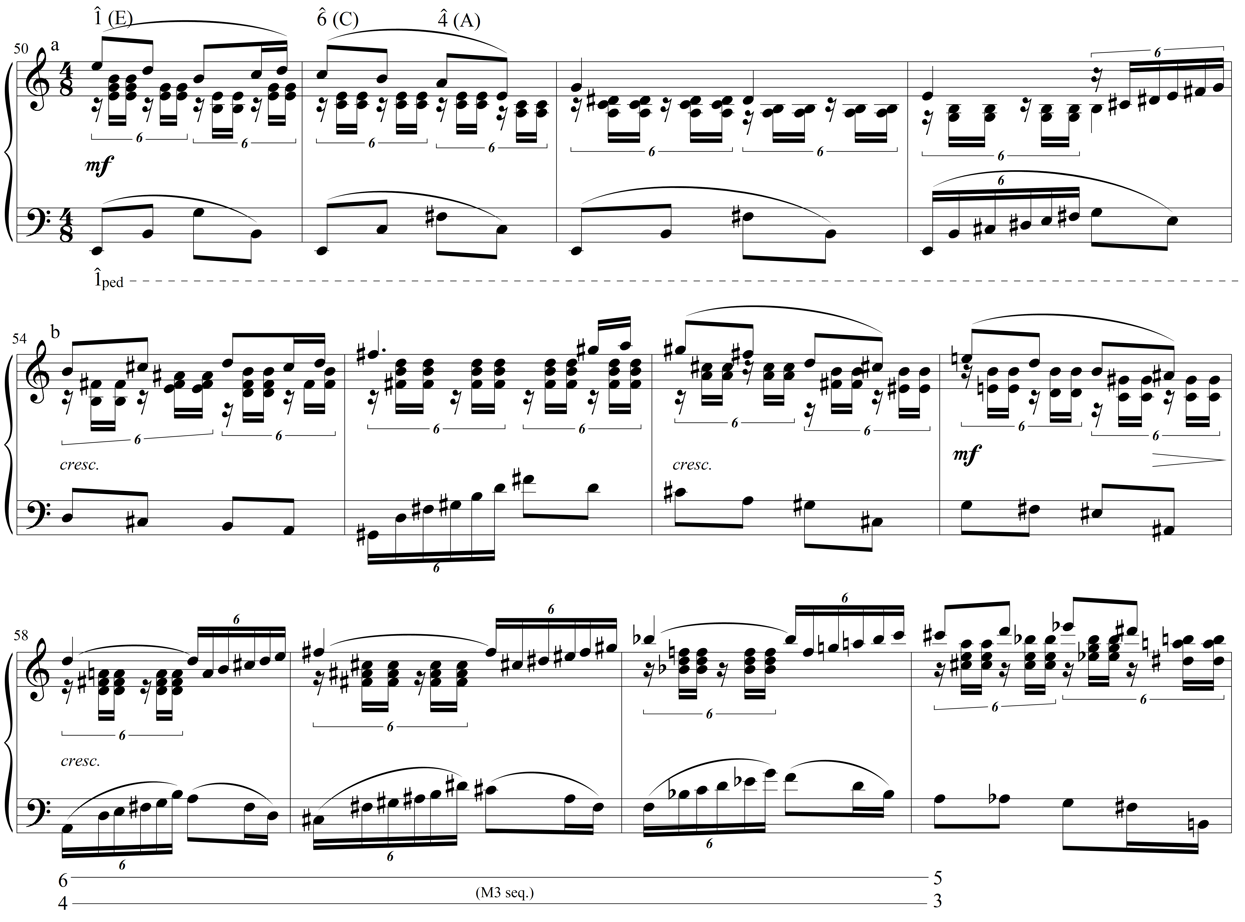

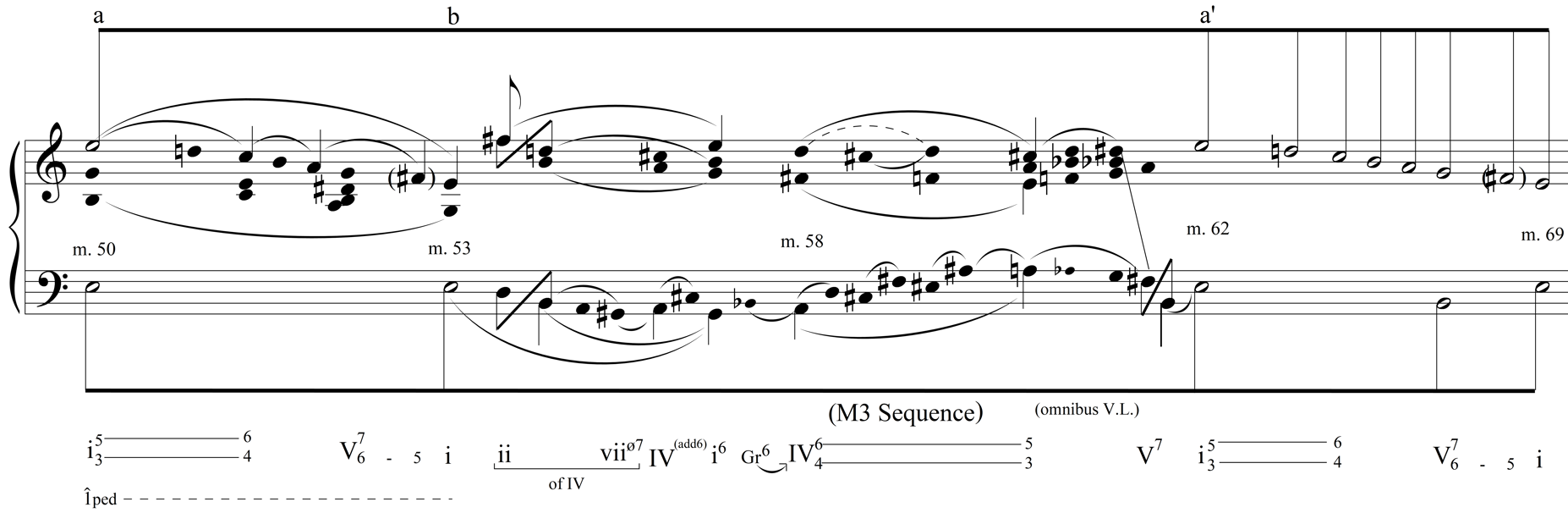

The C section, a small ternary form in E minor, is shown (without the reprise) in Example 3a. Like the A and B sections, this section also derives its melodic structure from the same A–C–E motif that characterizes those preceding sections. Here, however, the impression of pendular thirds is supressed, as the diatonic scale of common-practice tradition becomes the primary syntactic device. As shown in Example 3b, the a section comprises an octave descent from $$\hat8$$ to $$\hat1$$ over a tonic pedal. Within this descent, A, C, and E are all emphasized through rhythmic and harmonic accentuation: the opening E is harmonized by the tonic, while A and C are supported by the subdominant six-four shift in the second measure. Ultimately, the C ($$\hat6$$) resolves down to B, while the A ($$\hat4$$) resolves down to G, contextualizing themselves as common-practice dissonances in contrast to the pendular treatment of these pitches in the A sections.

The contrasting middle of the C section’s small ternary (mm. 54–61) is a harmonically adventurous fantasia-like passage that showcases Price’s virtuosity in the Romantic style, while also foregrounding the subdominant implications of the A–C–E motif hinted at in the a section. A brief tonicization of the subdominant (A) moves the E-minor tonic from root position to first inversion. The subdominant is then emphasized a second time, this time by way of a quasi-German augmented sixth chord in m. 57 that tonicizes it.18 This subdominant, however, is not projected in root position but rather as a six-four sonority over A in the bass (what appears as a second-inversion D-major triad) that initiates an ascending major-third sequence of major triads. Owing to the previous subdominant emphasis, as well as the preceding quasi-augmented-sixth chord applied to A, I read this sequence as prolonging the subdominant, with the sixth (D) and fourth (F$$\sharp$$) above acting as accented dissonances that eventually resolve down to the more stable C$$\sharp$$ and E to create the complete A-major triad.19 Following the complete subdominant triad in m. 61, omnibus-like voice leading patterns initiated by a third-inversion B$$\flat$$7 harmony (itself also vii$$^{\circ}$$$$^{\hphantom{\flat}7}_{\flat3}$$ of A) induce the music toward the dominant on the final two eighth-note beats of the same measure, setting up a return to the a section in m. 62.

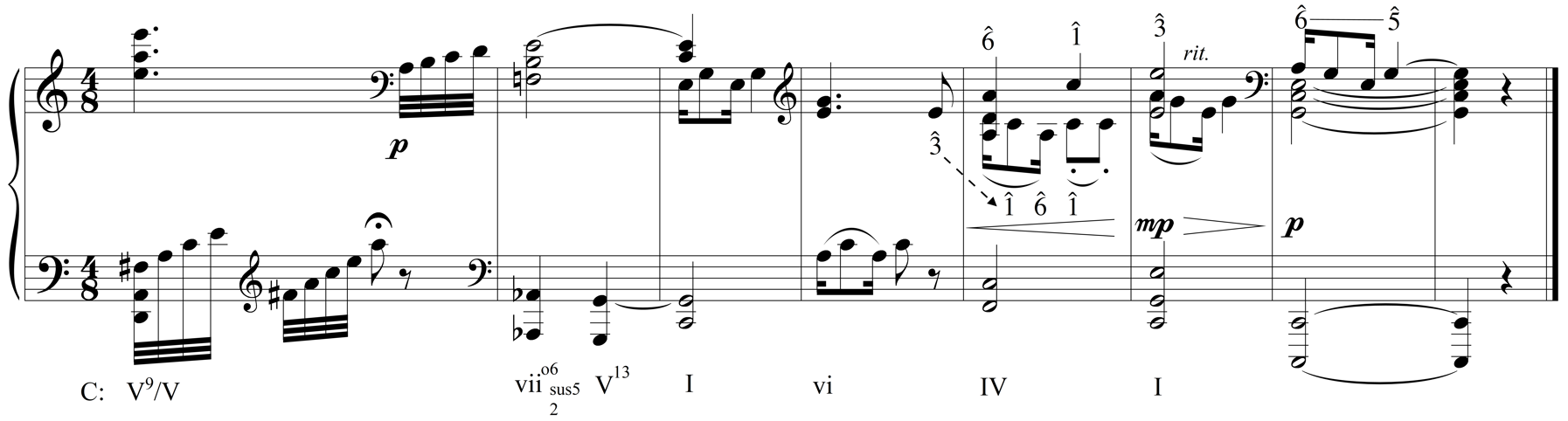

Following a brief retransition (mm. 70–80), the final, compressed, reprise of A presents a repetition of mm. 1–4 (mm. 81–84), as well as the second, more chromatic repetition (mm. 85–89). The third repetition is omitted, and instead what follows is a short coda (mm. 90–102). After averting a cadence in m. 90, a second attempt to reach closure, shown in Example 4, is made at mm. 95–97. The underlying harmonic framework of this cadence is D–G–C, with various additions and alterations, but which should support the melodic descent from $$\hat3$$, through $$\hat2$$, to the tonic. But the cadential progression is also obscured by the imposition of E above each of these harmonies: E acts as the ninth above D, as a thirteenth above the dominant, G, and sustains into the tonic triad. Indeed, E’s persistence undermines the sense of a melodic descent, such that even if one were to hear the C in m. 97 as more strongly articulated than the fading E above it, the sense of conclusion is still one of $$\hat3$$–$$\hat1$$, rather than $$\hat3$$–$$\hat2$$–$$\hat1$$, which I view as yet another manifestation of thirds in a pendular relationship with the tonic. A final plagal extension via vi and IV supports one last $$\hat6$$–$$\hat1$$–$$\hat3$$ arpeggiation in mm. 99–100, before the $$\hat6$$ finally relinquishes, resolving down to $$\hat5$$ over the final tonic chord.

2. Discussion

My analysis has focused on the motivic and structural salience of the A–C–E motif in various permutations throughout this rondo movement. In its original C-major context the motif reflects $$\hat6$$ and $$\hat3$$ in a pendular relationship with $$\hat1$$, a relationship that also echoes and reinforces the pentatonic nature of the melody and can be seen as an invocation of a Black topic in the pitch domain of the A section. This motif is, however, adaptable: it is tonic-reifying in the A-minor context of the B section, while espousing subdominant connotations in the E-minor context of the C section. Moreover, the motif is not confined to the musical surface, and appears in a variety of middleground permutations as well, including a harmonic motif in the presentation phrase of the A section, a deeper-level melodic motif in the continuation phrase of that same section, as well as the structural bass for the B section (which moves from A to C to E, and back to A). Furthermore, a recursion between E and A forms the primary harmonic drama in the C section.

What I have yet to discuss, however, is that the pendular inclinations of the A–C–E motif that draw $$\hat6$$ and $$\hat3$$ toward the tonic in C major also characterize the deepest-level structure of the movement. As shown in Example 5, the keys of the B and C themes are A and E respectively, and in keeping with the processes of a rondo, return to the tonic via the restatements of the refrain. The pendular third-relations that characterize the primary melodic-motivic material of the piece thus permeate beyond the musical surface in enlarged and expanded forms across all levels of the movement’s harmonic and melodic structures. In these remarkable parallelisms Price cultivates what I see as a distinct narrative of synthesis between her artistic and cultural heritage infused into the musical forms within which she was working: rather than a structure that outlines and prolongs a triad, the structure of this movement might be seen to project and emphasize the pentatonic collection defined by the pendular relationships between $$\hat6$$–$$\hat1$$, and $$\hat3$$–$$\hat1$$. Price, in other words, retains classical tonality and formal conventions as organizing principles, but transforms those conventions in ways that “became personal expressions and intrinsic reflections of [her] own cultural heritage” (Brown 1993, 197), refusing to allow these musical emblems to be subordinated to the overarching classical and romantic structures in which they reside.

To me, this synthesis does not appear accidental since Price herself was keenly aware that her music straddled multiple cultural aesthetics:

Having been born in the South, and having spent most of my childhood there I believe I can truthfully say that I understand the real Negro music. In some of my work I make use of the idiom undiluted. Again, at other times it merely flavors my themes. And at still other times thoughts come in the garb of the other side of my mixed racial background. I have tried, for practical purposes to cultivate and preserve a facility of expression in both idioms (Price to Koussevitzky, July 5, 1943, cited in Brown 1993, 197–199).

However, Price also “knew that the musical world viewed her work through the filter of stereotypes,” including those of gender and well as race (Brown 2020, 190). In the same letter to Koussevitzky, Price begins with the statement: “I have two handicaps—those of sex and race. I am a woman; and I have some Negro blood in my veins” (Brown 2020, 186). As Alex Ross describes, Price “plainly saw these factors as obstacles to her career” and “had a difficult time making headway in a culture that defined composers as white, male, and dead. One prominent conductor took up her cause—Frederick Stock, the German-born music director of the Chicago Symphony—but most others ignored her, Koussevitzky included” (2018).20

With these contexts in mind, it becomes impossible to avoid considering the treatment of black musical emblems in this piece, as well as the ways in which various elements of these emblems ‘code switch,’ as perhaps representing a musical reflection of Price’s heritage and experiences. The A–C–E motif, which as described previously adopts a pendular/pentatonic disposition in the refrains described as “reminiscent of Negro Spirituals” (Holzer 1995, 58),21 while serving more diatonic structural roles in the B and C sections, might be seen to have autobiographical implications, given Price’s mixed heritage and facility of expression in both idioms. But perhaps more prominently, the ways in which Price treats the black musical topics in this piece—not as outsiders, or others, that represent problems for the musical structure, but rather as structural elements that blend, fuse, and meld easily with the common-practice elements—articulates a narrative strategy in this piece distinct from the “overcoming” or “integration” narratives typically attached to composers such as Beethoven or Schubert. Typical tonal narrative strategies for common-practice music often invoke the concept of “heroic overcoming” (Straus 2011, 64), which manifests through normalizing traditional tonal structures and syntaxes while treating elements outside these structures and syntaxes as problems to be subdued. Joseph Straus, following Schoenberg (1967; [1948] 1984), refers to these elements as tonal problems: “musical events, often a chromatic note, that threaten to destabilize the prevailing tonality” (2011, 48). In such cases, the music “contrasts its normative content with a disruptive, deviant intrusion whose behavior threatens the integrity of normal functioning of the musical body” (2011, 48–49).22 But for Price, the black emblems in this movement resist interpretations that might place on them the role of an intruder to the classical structures in which she was working. This resistance can be seen through the ways in which the emblems permeate the musical surface and interact with the more common-practice idioms that characterize the B and C sections, but also in the ways that pendular thirds generate the larger-scale tonal structure of the movement. Resistance can be seen in the ways $$\hat6$$ strives to create a place for itself as an equal to $$\hat5$$ within the tonal framework, avoiding subordination to the tonic triad. Price, likewise, dealt with a societal framework that often denied her compositional voice as equal to those of the white, male, often European composers. Yet she too, resisted, and continued to advocate for herself, her work, and her artistic vision “of using Negro folk materials in large-scale compositions” (Brown 2020, 4–5).

This suggests to me that it is not enough, as some have proposed, to simply “publish some sophisticated analytical graphs of works by black composers” (Beach 2019, 128). Doing so may indeed be a first step, but on its own runs the risk of failing to accurately capture much of what makes Price’s music—or, indeed, any music that adopts a plurality of cultural influences—unique: the compelling, and often subtle fusing of multiple vernacular musical idioms. Indeed, as Brown describes, “African American composers in the early twentieth century…often utilized and transformed classic/romantic structures into forms that became personal expressions and intrinsic reflections of their own cultural heritage” (Brown 1993, 197), which appears especially true for Price’s style. Given the interactions between two cultural styles that characterize this sonata, any analysis that proceeds on the assumption that the underlying tonal language presupposes common-practice syntactic normalcy without integrating considerations of the Black vernacular musical tropes that may underly the music risks mischaracterizing and misconstruing not only the musical tropes, but the entire underlying structure of the music.23

I close by reenforcing the views I have projected through the analysis, that Price was able to harmonize both her cultural heritage with her classical training, and thereby produce something unique: a synthesis between the two wherein a motif (A–C–E) that is cast at first in a pendular relationship within a pentatonic idiom finds expression in later sections in a more Western vernacular, while never losing, and always returning to, its pendular and pentatonic identity. As Maxile Jr. concludes, “Price…exhibits dexterous handlings of African American musical emblems within a Western framework, presenting them not as exclusive entities but as complementary elements that inform and foreground her craftmanship as well as the core of her aesthetics” (2022, 161). My hope is that this article demonstrates that these emblems are indeed incorporated in such a way as to serve not only as surface-level references to Black vernacular idioms, but rather form the underlying melodic and harmonic structure of the movement: they exist in harmony with, rather than in opposition to, the more Western classical structures of the work, and Price’s fusion of the two through a dexterous unfolding of structural parallelisms suggests a far more intricate and detailed craftmanship, one that I am hopeful close studies of other works might continue to develop and reinforce.

References

Agawu, V. Kofi. 1991. Playing with Signs: A Semiotic Interpretation of Classical Music. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Alegant, Brian, and Donald McLean. 2001. “On the Nature of Enlargement.” Journal of Music Theory 45/1: 31–71.

Beach, David. 2019. “Schenker–Racism–Context.” Journal of Schenkerian Studies 12: 127–128.

Brown, Rae Linda. 1993. “The Woman’s Symphony Orchestra of Chicago and Florence B. Price’s Piano Concerto in One Movement.” American Music 11/2: 185–205.

———. ed. 1997. Price: Sonata in E Minor for Piano. New York: Schirmer.

———. 2020. The Heart of a Woman: The Life and Music of Florence Price. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Charters, A.R. 1961. “Negro Folk Elements in Classic Ragtime.” Ethnomusicology 5/3: 174–183.

Clark, Suzannah. 2007. “The Politics of the Urlinie in Schenker’s Der Tonwille and Der freie Satz.” Journal of the Royal Musical Association 132/1: 141–164.

Cone, Edward T. 1982. “Schubert’s Promissory Note: An Exercise in Musical Hermeneutics.” 19th-Century Music 5/3: 233–41.

Day-O’Connell, Jeremy. 2002. “The Rise of 6 in the Nineteenth Century.” Music Theory Spectrum 24/1: 35–67.

———. 2009. “Debussy, Pentatonicism, and the Tonal Tradition.” Music Theory Spectrum 31/2: 225–261.

Ege, Samantha Hannah Oboakorevue. 2020a. “The Aesthetics of Florence Price: Negotiating the Dissonances of a New World Nationalism.” Ph.D. diss., University of York.

———. 2020b “Composing a Symphonist: Florence Price and the Hand of Black Women’s Fellowship.” Women and Music 24: 7–27.

———. 2021. “Chicago, the ‘City We Love to Call Home’: Intersectionality, Narrativity, and Locale in the Music of Florence Price and Theodora Sturkow Ryder.” American Music 39/1: 1–40.

Ewell, Philip. 2020. “Music Theory and the White Racial Frame.” Music Theory Online 26/2. https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.20.26.2/mto.20.26.2.ewell.html.

Feagin, Joe. [2009] 2013. The White Racial Frame: Centuries of Racial Framing and Counter-framing. 2nd. ed. Routledge.

Floyd Jr., Samuel A. 1995. The Power of Black Music: Interpreting its History from Africa to the United States. New York: Oxford University Press.

———. 2008. “Black Music and Writing Black Music History: American Music and Narrative Strategies.” Black Music Research Journal 28/1: 111–121.

Hepokoski, James, and Warren Darcy. 2006. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late Eighteenth-Century Sonata. New York: Oxford University Press.

Heyer, David J. 2012. “Applying Schenkerian Theory to Mainstream Jazz: A Justification for an Orthodox Approach.” Music Theory Online 18/3. https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.12.18.3/mto.12.18.3.heyer.html.

Holzer, Linda. 1995. “Selected Solo Piano Music of Florence B. Price (1887–1953).” Doctoral Treatise, Florida State University.

Hutchinson, Kyle. 2020. “Chasing a Chimera: Challenging the Myths of Augmented-Sixth Chords.” Theory and Practice 45.

———. 2022. “Chromatically Altered Diminished-Seventh Chords: Reframing Function Through Dissonance Resolution in Late Nineteenth-Century Tonality. Music Analysis 45/1: 94–144.

———. 2023. “The Predominant Six-Four in the Late Music of Richard Strauss.” Music Theory Spectrum 45/1.

Lewin, David. 1986. “Music Theory, Phenomenology, and Modes of Perception.” Music Perception: an Interdisciplinary Journal 3/4: 327–392.

Martin, Henry. No date. “From Classical Dissonance to Jazz Consonance: The Added Sixth Chord.” Unpublished Manuscript.

Maus, Fred Everett. 1991. “Music as Narrative.” Indiana Theory Review 12: 1–34.

Maxile Jr., Horace J. 2008. “Signs, Symphonies, Signifyin(G): African-American Cultural Topics as Analytical Approach to the Music of Black Composers.” Black Music Research Journal 28/1: 123–138.

———. 2022. “Culture and Craft in Florence Price’s Piano Sonata in E minor (First Movement).” In Analytical Essays on Music by Women Composers: Concert Music 1900–1960. Edited by Laurel Parsons and Brenda Ravenscroft, 139–163. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mirka, Danuta. 2015. “The Mystery of the Cadential Six-Four.” In What is a Cadence? Theoretical and Analytical Perspectives on Cadences in the Classical Repertoire. Eds. Markus Neuworth and Pieter Bergé, 157–184. Leuven: Leuven University Press.

Narmour, Eugene. 1977. Beyond Schenkerism: The Need for Alternatives in Music Analysis. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Pomeroy, Boyd. 2003. “Debussy’s Tonality: a Formal Perspective.” In The Cambridge Companion to Debussy, ed. Simon Trezise, 155–178. New York: Cambridge.

Radano, Ronald M. 2003. Lying Up a Nation: Race and Black Music. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ross, Alex. 2018. “The Rediscovery of Florence Price.” In The New Yorker, January 29, 2018. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/02/05/the-rediscovery-of-florence-price

Schoenberg, Arnold. [1948] 1984. “Gustav Mahler.” In Style and Idea: Selected Writings of Arnold Schoenberg. Edited by Leonard Stein. Translated by Leo Black, 449–72. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

———. 1967. Fundamentals of Musical Composition. Edited by Gerald Stang and Leonard Stein. London: Faber & Faber.

———. [1922] 1978. Theory of Harmony. Translated by Roy E. Carter. Reprint. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Schmalfeldt, Janet. 1992. “Cadential processes: The Evaded Cadence and the “one more time” Technique.” Journal of Musicological Research 12/1-2: 1–52.

Straus, Joseph. 2011. Extraordinary Measures: Disability in Music. New York: Oxford University Press.

Van den Toorn, Pieter C. 1995. Music, Politics, and the Academy. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wilson, Olly. 1992. “The heterogenous sound ideal in African American music.” In New Perspectives in Music: Essays in Honor of Eileen Southern. Edited by Josephine Wright and Samuel A. Floyd Jr., 327-338. Warren, Michigan: Harmonie Park Press.

Notes

- In describing black topics within “classical” settings, Maxile Jr. follows a line of scholarship that situates black concert music as espousing pluralistic cultural influences. Olly Wilson, for instance, notes that African American music “has both influenced and been influenced in several ways by non-black musical traditions” (1992, 327–28). In his 2003 monograph Lying Up a Nation, ethnomusicologist Ronald Radano writes that “Situating black music within the texture of American life means no longer easily separating ‘black music’ from ‘white music,’ nor, indeed, black music from the rest of the social experience” (2003, 4). Radano’s argument concerns engaging critically with “legacies of race, themselves Eurocentric, in order to move toward a more socially informed interpretive practice” by “giv[ing] up commitment to racial categor[ization]” (2003, 4). Samuel A. Floyd Jr. likewise advocates for “study of how Africans transformed European musical genres in ways that made them their own, and how African Americans continued to transform them to the extent that they became recognizably American” (2008, 118), which he describes as an “intercultural crossroads of black and white in the United States…the understanding of which is crucial to constructive social, political, and intellectual discourse” (1995, 270).

- The sonata won the Rodman Wanamaker Composition Contest in 1932, although as Linda Holzer notes, “the manuscript for the sonata is not dated, and it is unclear whether the piece was composed in 1932, or simply awarded a prize in a competition in 1932” (1995, 52). Samantha Ege (2020b, 20) describes the history of the Wannamaker contests: “Founded in 1927 by philanthropist and storeowner Rodman Wannamaker, the contests were born out of his desire to create a platform that exclusively elevated black composers. The contests attracted a great number of submissions countrywide, and strongly encouraged classical scores that engaged black musical idioms.”

- Alegant and McLean describe enlargement as a process whereby “a surface (or near-surface) object … is subsequently ‘enlarged,’ or re-presented in temporally expanded form” (2001, 31).

- Maxile Jr. borrows the term pendular thirds from Samuel A. Floyd Jr’s The Power of Black Music: Interpreting Its History from Africa to the United States. Maxile Jr. notes that “Floyd employs this term often when describing melodic practices…but does not offer a firm definition of the term.” (2022, 162, fn. 7).

- Edward T. Cone defines congeneric meaning as “relationships entirely within a given medium…Congeneric meaning thus depends on purely musical relationships: of part to part within a composition, and of the composition to others perceived to be similar to it. It embraces the familiar subjects of syntax, formal structure, and style” (1982, 234). Extrageneric meaning, conversely, refers to “the supposed reference of a musical work to non-musical objects, events, moods, emotions, [or] ideas” (1982, 234). Cone, however, contends that “extrageneric meaning can be explained only in terms of congeneric” (1982, 235).

- Linda Holzer draws this dichotomy of styles even more starkly, suggesting that while the sonata “reflects Romantic ideals within a Classical form…[the] sonata is unique for the solo piano repertoire of its time in that it is a synthesis of elements of Negro folk music with elements of nineteenth-century virtuoso Romanticism” (1995, 52). Price, who had earned a degree in music from the New England Conservatory in 1906, would have been intimately familiar with the Romantic style. As Brown (2020, 52–53) notes, Price performed works by Robert Schumann, Francois Theodore Dubois, and Felix-Alexandre Guilmant while studying. Brown also gives an overview of the New England Conservatory, noting that while it began as a school that “placed a heavy emphasis on European musical training,” when George Whitefield Chadwick was named director of the conservatory in 1897, he “sought to change the direction of the New England Conservatory (2020, 42)”. Specifically, Brown describes how “Chadwick moved quickly to raise the academic standard of the Conservatory…[modifying] the curriculum from its earlier emphasis on singing and piano playing to one that stressed harmony, counterpoint, theory and analysis, and composition.”

- Ege (2020a, 98–99) also suggests that the melodic material for this movement derives in part from Harry T. Burleigh’s 1917 arrangement of the Negro Spiritual “By an’ By.”

- “Inflected pitches and modal ambiguities characterize melodic practices in many forms of African American music both sacred and secular, and such inflections when realized in popular forms are often referred to as blue notes or bent notes. The inflections often involve the seventh scale degree, but other scale degrees can also be altered.” (2022, 141).

- I describe the efficiency of interpreting the function of augmented-sixth chords as alterations of dominant-functioning vii$$^{\circ}$$7 chords, especially the German augmented-sixth as vii$$^{\circ}$$$$^{\hphantom{\flat}7}_{\flat3}$$ applied to whatever scale degree it tonicizes, in Hutchinson 2020.

- In eighteenth-century common-practice tonality, a sixth over the tonic triad is typically treated as a dissonance that resolves to the more consonant fifth—as in, for instance, the opening of the second movement of Schubert’s Piano Sonata D.664—such that the hierarchic relationship between the two is made clear. See for instance Day-O’Connell (2002, 38–39), who describes common-practice conceptions of $$\hat6$$ as almost unilaterally recommending that it descend to $$\hat5$$ as a dissonance. Heyer (2012) also discusses the structural aspects of add6 chords in relation to a Schenkerian framework, noting that “an orthodox approach requires $$\hat6$$ to ultimately derive its meaning from a more stable pitch at a deeper level of structure.”

- I make this distinction to highlight the possibility, following contentions by David Lewin (see especially 1986, 357–58) that different listening expectations might engender different interpretations and anticipations regarding the function of $$\hat6$$ in this initial chord in phenomenological listening space: one might equally anticipate that A will function as a structural dissonance, or that it is an added note to the tonic triad.

- A.R. Charters describes that “Ragtime melodies are not only written in the standard major and minor scales, but frequently take on the characteristic intervallic relationships of pentatonic, or mixed major-minor scales” (1961, 175). Charters further notes that “the pentatonic scale…is very important in African music…and the prevalence of the pentatonic scale in early American Negro music may be attributed to the fact that it formed the most obvious common denominator between the native African idioms and the harmonically dominated music of the white hymn tunes” (1961, 176).

- As Heyer (2012, 2.2) suggests, “[Prolongational] views [require] $$\hat6$$ to ultimately derive its meaning from a more stable pitch at a deeper level of structure—a level of structure consistent with common-practice harmony. Citing an unpublished article by Henry Martin (Martin, no date), Heyer (2012, 2.1) summarizes Martin’s claim that “a $$\hat6$$ supported by the tonic serves one of three functions: (1) a dependent non-chord tone (a surface-level embellishment of $$\hat5$$), (2) an independent chord tone (reducible only at a deeper level of structure), and (3) an inclusive chord tone (consonant and therefore left unreduced).” Mirka (2015) also engages in an encompassing overview of the historic context of consonance-dissonance debates regarding the sixth in six-four chords.

- As Day-O’Connell notes, “the minor third $$\hat3$$–$$\hat5$$, in fact forms a structural element of classical diatonic tonality, comprising as it does two notes of the (stable) tonic triad” (2009, 235).

- Day-O’Connell (2002, 51–5) discusses the $$\hat6$$–$$\hat8$$ motion as a distinct type of cadential figure that arose in the nineteenth century.

- More specifically, Ege’s analysis focuses on texture and dynamics, as well as harmonic color in the repetitions of the theme.

- There is, however, some fluctuation between the leading tone and subtonic tones, a feature from the first movement which Maxile Jr. interprets as “link[ed] to many African American musical styles and practices” (2022, 145).

- I read the function of this chord as defined by the interactions between the G$$\sharp$$ and the F$$\natural$$, which in resolving to A/E (the E is delayed by the sequence) signal themselves as $$\hat7$$/$$\flat\hat6$$ circumscribing $$\hat1$$/$$\hat5$$ in a local tonicization of A (see Hutchinson 2022, where I develop these theories more explicitly). The B$$\flat$$ is the lowered supertonic of A (as in any German augmented sixth), while the C$$\natural$$ is a somewhat perplexing dissonance, perhaps best read as a displacement of the preceding D$$\natural$$ (which would complete the German augmented-sixth sonority).

- I make a case for the “predominant six-four” in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century music specifically as a phenomenon of displaced voice-leading over lengthy temporal spans in Hutchinson 2023.

- Racism, of course, was not confined to Price’s artistic life, but was rather something she had always dealt with. As Brown describes, “Price and her family moved to Chicago to escape the oppressive legalized social proscriptions of the South. While she lived in Little Rock, her way of life as a Negro woman, to some extent, had been determined for her. The ‘Jim Crow’ laws forced her to abdicate her rights, but she soon realized that no one could take away her self-esteem…[and] it was in Chicago that Price’s artistic impulse was liberated” (Brown 2020, 5). Brown further suggests that the reason the Prices left Arkansas was to avoid racist violence: “In late 1927 a white child was allegedly killed by a black man. The white community was out for vengeance—black blood. Whites wanted to retaliate by killing a ‘comparable’ black child…the apparent victim was to be Florence Price’s youngest daughter, Florence Louise. With no hope that the police would intervene and give them protection, Florence Price and her two daughters fled to Chicago for safety…” (2020, 79).

- The use of $$\hat3$$ to avoid closure in the final A section likewise suggests that the music in A comprises a more jazz-like idiom, with the chordal thirteenth being treated as hierarchically unrelated to the $$\hat2$$ from which it is meant to be derived structurally (again, see Heyer 2012).

- Straus describes the C$$\sharp$$ in the first movement of Beethoven’s Third Symphony, as well as the G$$\flat$$ in the first movement of Schubert’s Piano Sonata in B$$\flat$$ major D.960 as reflecting such narratives. Cone describes a similar interpretation of E$$\natural$$, what he terms a “promissory note,” in Schubert’s Moment Musical op. 94, no. 6 (1982, 235). “Promissory status in music of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries,” Cone explains, “is demanded, or at least requested, by a note—or more accurately, though less paronomastically, an entire chord—that has been blocked from proceeding to an indicated resolution, and whose thwarted condition is underlined both by rhythmic emphasis and by relative isolation. Rhythmic emphasis, of course, results from the stressed position of the chord within (or outside of) a phrase, from special agogic or dynamic inflection, or from a combination of those. Isolation is effected not only by the motivic detachment that often separates such a chord from its surroundings, but also by harmonic novelty. The promissory chord is promoted, so to speak, by an insurrection that tries, but fails, to turn the course of the harmony in its own new direction” (1982, 236). While there is nothing inherently wrong in reading these pieces this way—Straus’s discussion of these narratives in relation to disability studies is particularly enlightening—such narratives also typically centralize eighteenth- and nineteenth-century European values—outsider ‘threats’ to the governing tonic-dominant hierarchy must be eradicated to “reach a satisfactory state” (Maus 1991, 13)—and prioritize events experienced from within the hierarchy: a “white worldview [encompassing] persisting. . .racial prejudices, ideologies. . .interpretations and narratives” (Feagin [2009] 2013, 3).

- Ewell (2020) makes a case that in the field of music theory, “whiteness—specifically the music and theories of white people—are given systematic precedence, and advantage over the music and theories of non-whites,” and it is typically assumed that “[t]he music and music theories of white persons represent the best, and in certain cases the only, framework for music theory.” One might thus consider that an analysis that simply applies tonal-linear theories to Price—perhaps in order to prove the theory works with her music rather than highlighting Price’s music—might be similarly reinforcing such a frame. Suzannah Clark describes how in Schenker’s later work he became fixated on demonstrating how “everything manifested through a replicating prototype” (2007, 162), a trope which in my view has the unfortunate consequence of cultivating a desire to fit any analyzed music into the same replicating Procrustean bed. As Pieter C. Van den Toorn suggests, one common criticism of analysis—particularly that of the Schenkerian variety—is that “in working with general notions and concepts, with the mechanical reproduction of those notions and concepts from one musical context to the next, [analysis ignores] the individual qualities or salient features of those contexts. In ignoring individuality, [analysis] ignores ‘presentness’ as well, the felt presence of individual works” (1995, 21). Eugene Narmour’s criticisms of Schenkerian methodology similarly posit that “to permit I and V to operate [as privileged elements] is to allow certain favored relations to predetermine [emphasis Narmour’s] structural features of certain individual works of art” (1977, 15), a tactic which I have attempted to avoid in this analysis by emphasizing that it is the A–C–E motif that is prominent, rather than the C-major tonic triad. My own view is that linear/structural analysis is at its most useful when it can demonstrate or say something interesting about why the music is unique—whether this is in terms of composing-out motifs, recursive parallelisms across levels, or interesting treatments of dissonant tones. I have, in this work, attempted to use linear analysis to focus on and say something meaningful about Price’s music, rather than having the analysis serve as a demonstration of the analytic methodology.