Memphis Symphony Orchestra

The Memphis Symphony Orchestra started out as the Memphis Sinfonietta in 1953 with 21 musicians, conducted by Vincent de Frank. The organization gradually grew into a full symphony by 1960.

Throughout its history, the MSO has had only four music directors: Alan Balter replaced Maestro de Frank in 1984. Less than a year after Balter retired in 1998, David Loebel joined the symphony, serving as music director until 2010. Mei-Ann Chen was named the orchestra’s fourth music director in February 2010 and began her tenure in the fall of 2010.

The MSO is fortunate to perform in a fairly new hall, the 2,100-seat Cannon Center for the Performing Arts, which opened to rave reviews in January 2003.

But currently Memphis is best known for its innovative community engagement programs, which bring MSO musicians into the community in a variety of very unusual ways. The orchestra recently announced that they will be receiving $1 million in support of their community engagement and professional support of musicians: $550,000 from the Mellon Foundation, $400,000 from the Plough Foundation, and $75,000 from the Thomas Briggs Foundation. This spotlight will profile a few of these community engagement activities, but first, a myth must be dispelled.

The term “Memphis Model” has been circulating among musicians and managers since early 2010, meaning that MSO musicians are performing office tasks and community outreach performances for “service conversion” – using services usually spent in rehearsals and concerts to carry out these non-traditional tasks. This is simply not true. No MSO musicians work in the MSO office, and all MSO musicians who decide to opt in to the extra community engagement activities are paid additional monies, according to a formula clearly spelled out in their contract.

The misperception, which is popping up at negotiations across the country, stems from the American Orchestras Summit meeting in January 2010 in Ann Arbor, Michigan. MSO President, Ryan Fleur, who was asked to attend at the last minute to replace Jesse Rosen of the League, talked about the community engagement activities in Memphis and, according to Ryan, he misspoke. His comments were disseminated on several blogs after the Summit, in particular that of Joseph Horowitz, and the misperception persists. I asked Ryan about the Ann Arbor meeting and the controversy about “the Memphis Model” in our interview. (See page 2.)

Michael Barar, MSO violist and former chair of the orchestra committee, first heard the term “Memphis Model” during the opening remarks at the ROPA conference in August, 2010, and was rather stunned, to say the least. He carefully refutes the charge, and explains the nature of the compensation received by MSO musicians who choose to opt into the community engagement activities. (See page 3.)

Gaylon Patterson, MSO acting principal 2nd violin, and Lisa Dixon, former Chief Operating Officer and now Executive Director of the Portland (ME) Symphony, give us an overview of how Leading from Every Chair® got started, and the impact these new activities have on the city’s perception of their symphony. (See page 4.)

Susanna Perry Gilmore, MSO concertmaster, was instrumental in developing the Opus One concert series. She explains how this all came about and describes the concerts. (See page 5.)

Rhonda Causie, Director of Grants and Innovation, has not only a highly unusual title but also a highly unusual role in the Memphis Symphony. She’s the point person for musicians who want to try to do something unusual or different – and she puts together a logic model to see if it can work! (See page 6.)

Frank Shaffer, MSO timpanist, and Jennifer Puckett, MSO principal violist, were original members of the group that is mentoring students at Soulsville Charter School. They describe the Memphis musicians’ roles at the school. (See page 7.)

Frank Shaffer is now leading drum circles at Youth Villages, a facility for kids with serious problems, and is totally energized by the experience. (See page 8.)

And finally, Tony Woodcock, President of the New England Conservatory, stopped by Memphis on his way home from a conference and has some thoughts to share about the controversy, as well as an interesting blog post. (See page 9.)

Ann Drinan, Senior Editor

March, 2011

The Memphis Symphony has made a montage video, showing some of their many community engagement activities. Take a look to watch Leading from Every Chair and Soulsville mentoring in action.

Ryan Fleur

President and CEO

Ann Drinan: How would you describe Memphis?

Ryan Fleur: Memphis is a city with great people and wonderful charm. Our economy is built on being a distribution hub, with FedEx our largest local employer. I’ve read that 95% of every good consumed west of the Mississippi passes through Memphis on a train. Our musicians have moved here from all around the world to play with us, and since we are geographically isolated as a community (you must go 300 miles north to St. Louis, 200 miles east to Nashville, 400 south to New Orleans, or 400 west to Dallas to find the next communities with full-time professional orchestral talent), we need a full-time base of artists here for our orchestra to be relevant to the Memphis community. We also need a base of artists living here to provide lessons for our kids, music in the schools, and to have creative people living in the area.

Memphis has a really deep music history, though most Memphians do not associate that music history with classical music. We are surrounded by the blues, rock ‘n roll, and Elvis.

Finally Memphis has a truly diverse population – we are the first major metropolitan area in the U.S. to be majority-minority. There is wide economic disparity in the population, as well, with over one-third of all Memphians living below the poverty line.

What does it mean to be an orchestra that plays symphonic music for a community that has these qualities?

This is the question we asked when we began this whole journey of transformation. If we went out of business, why would 98% of the population of Memphis care or would they even notice?

Traditionally, the question is about artistic excellence – how do you make great music? How do you sell more tickets? Raise more money? And so the traditional symphony structure has a CEO, departments that handle raising money, selling tickets, a volunteer committee that puts on a gala, etc.

But what if these are the wrong questions for Memphis? What then are the right questions? We’ve been talking about this for a long time.

What if service became the center, and artistic excellence became not our outcome but rather a means for delivering that service? We spent the first few years talking about it: What are the community needs you’re meeting by delivering a high level of performance? How do you provide consistent role models where 30% of the population lives below the poverty line?

What do you think is the right question?

Perhaps the right question would be: How do we serve Memphis through great music? What can the orchestra uniquely do, in ways that are artistically meaningful, that meet genuine community needs and are fiscally sustainable?

We have developed a 3-step value proposition that basically says we will do anything that meets the following criteria:

- It must be artistically meaningful to the musicians, whether the full orchestra or a smaller ensemble. The musicians must be passionate about it.

- It must meet a definable community need.

- We must determine that, by doing the above, it will generate revenue.

Said in another way, we need to surround ourselves with the right people, delivering the right service, resulting in sustainable revenue.

What has developed here in Memphis is the notion of music-led initiatives, which is a really critical factor. We are not a musician-run organization, but we’re trying to build a culture where it’s not all about telling people where to go and what to do. That’s obviously part of what we do – we have a schedule with dates and rehearsal/concert venues, etc. But there is not 38 weeks of demand to operate that way. How do we keep our musicians stimulated and let them create projects that will fulfill them through artistic excellence and community service?

Tell me how all your community engagement activities started.

It’s been a journey – it takes a long time to build trust, and transparency is critical to trust. We started with side letters to the master agreement and tried not to think outside the box but rather invent a new box. Given the economy, we couldn’t offer a pay increase but we wanted to extend this partnership work. Then we took what was in those side-letters and went a step further – if a musician wants to opt in to this work, s/he will be guaranteed a certain amount of incentive pay to do these activities, and incentive pay is tied to the principal service rate. We offered 15 or 30 units of time the first year. The next year we were able to fund that at the same time our base pay over 38 weeks had to be cut 10%. It was a weird dichotomy, but we had additional revenue for optional work which provided an incentive for musicians to do new things.

Where did the funding for the additional work come from? How did this help create the new activities you now pursue?

Through building these partnerships, we were able to capture the imagination of local funders who did not otherwise fund the orchestra. In addition, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation gave us a $40,000 planning grant, which directly assisted the artistic development of our Opus One series. I know Gaylon, Susanna, and others have explained how we used this grant. [See pages 4 & 5.]

Our budget went down to $3.5 million for a year in 2010. It was critical, in dialogue with our musicians, that we not cut musician positions. We determined that we would need to have five fewer subscription weeks, given that it’s cheaper to not have the orchestra play. Yet we decided to keep those weeks in our contract, meaning our musicians would be paid yet the Orchestra would essentially be dark. We also made it clear that we were open to any ideas our musicians had of how to utilize those weeks, as long as it met the 3-step value proposition.

It took seven months for an answer to emerge, and it was our Opus One series. [See page 5 for more information on Opus One.] The musicians realized that they needed to keep playing together, but the concerts had been cut back. The staff was much smaller than before, so they decided to produce these new concerts themselves.

There was a determination by our musicians to make this happen – it was a pretty radical experiment. What if no one young showed up? But the only real tragic failure would be if it didn’t work artistically. How are we going to learn to play with no conductor? David Loebel had moved to Cleveland, we didn’t have an assistant conductor (remember that geographic isolation I described). And that is where the planning grant from Mellon came in, which allowed us to work with the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra and have facilitated sessions in Memphis to develop our own system inspired by Orpheus. We found a creative way to solve a problem.

What’s the mistake we’ve made in all this? I have a 2004 quote from Alex Ross [the New Yorker music critic] posted here in my office: ”The future of music is local, not global. Every ensemble must justify itself to its community because the global economy has no use for a symphony orchestra playing Beethoven or… anything else.” And we came up with a local solution. We did not anticipate how our work would be perceived and distorted outside of Memphis.

I understand that a comment you made at an orchestra conference in Ann Arbor, MI, in January 2010 has been misinterpreted nationally, causing there to be much distress about “The Memphis Model” among musicians, and perhaps an opposite reaction among manager.

I just talked about local solutions. The mistake I made at the Michigan conference was in not thinking about controlling the story from a national perspective. We were trying things locally and I wanted to tell our story. What happened is that we let the story be told about us rather than telling it ourselves.

I was asked to attend the conference at the last minute. And I came with our local solution, which is completely unconventional. “We’re not taking the huge pay cut everyone else has had to take because we’ve found a way to fund alternative work.” And that, frankly, is the wrong interpretation of the facts. Joseph Horowitz, a classical music writer and former orchestra manager, said, “This is amazing. Do you mind if I write about it?” I agreed and it took off from there. [Click here to read Joe Horowitz’ blog entry about Memphis.] But they’ve misunderstood the nature of our alternate work – it’s optional, not service conversion.

Many other orchestra administrators have been inspired by their perceptions of what is happening in Memphis. Yet to my knowledge, no one has looked at the explicit language we put together in our CBA to ensure that what we do is true to the Memphis Symphony’s value proposition.

The whole point is that you can’t build trust or transparency in a proposal. All it takes is the administration or the board to do 2 or 3 things perceived as underhanded and it all crumbles like a house of cards. You’ve got to meet frequently and have honest discussions.

I hear you have a very unusual way of structuring your staff.

It was clear 2 ½ years ago that if we didn’t change how we did things, we were going out of business. We have not completely solved the revenue problem but we’re quite optimistic moving forward. We’ve seen lots of new revenue sources, both locally and nationally. So we realized that the staff can’t be part of the traditional model any more (Development, Marketing, Box Office, Finance, Operations, etc.)

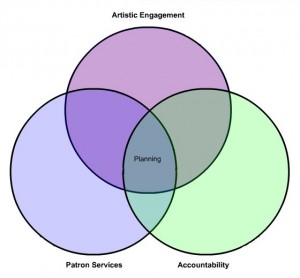

We have three areas. Artistic Engagement (Artistic Planning, Operations, Education) involves any way in which our artists are deployed. We’re trying to relate the fact that an hour of someone’s time is an hour of someone’s time – it’s equally valuable to them. Patron Engagement (Development & Marketing) involves the competency of selling tickets and raising money – anything that involves our patrons. But more than that it is about delivering consistent messaging and service to those people. The third circle is Accountablity (Finance), which measures what’s happening in the other two areas.

The center point where the three circles intersect is the Planning department – where organizational goals interface with the community and the board. This is also where pilot projects and innovations originate. Rhonda Causie, our grant writer [see page 6], is very much the center here. When you get a grant, you’re experimenting for a few years. She has ownership of that – she’s working with other staff and helps them be the custodian for those projects.

This structure comes from my own belief that in being a CEO of an orchestra, your responsibility is not to solve the organization’s problems, but rather to articulate the opportunities and empower other people to come up with the solutions. Being an orchestra CEO is somewhat of a misnomer. Given the traditional orchestral structure, the CEO has the ultimate responsibility and accountability, yet relatively little authority. You and the music director have to inspire people, but essentially, they have to be motivated from within.

What do you see in the future for the MSO?

The Memphis Symphony has not yet achieved long-term financial stability but by doing all these things we’re still in business and we have a path to success. We’ve captured the imagination and attention of a much wider circle of Memphians who will ultimately help us change our own business model. Now we’re in lag time – in the business world it takes 5 years before you find the full revenue return on an investment. With part of the new Mellon grant, we will really invest in Leading from Every Chair® and it should bring in meaningful earned revenue, from completely new sources, within a year or two.

The approach we have here, essentially, is totally based on trust and transparency. It can work with any orchestra. We’re still learning. It’s messy, it takes time, and you can’t be afraid of the bumps on the road.

I remember from the Ann Arbor conference, a professor from Ross School of Business school said, “If the Internet is so accessible, and I can stream a Berlin Philharmonic performance from my laptop, meaning I can get the best at an affordable cost, why should I go hear my local orchestra?”

We need to answer that question!

Michael Barar

Violist and Recent Orchestra Committee Chair

Ann Drinan: As I mentioned in my introduction, you never heard the phrase “Memphis Model” until you attended the ROPA conference in Omaha in August, 2010.

Michael Barar: That’s right. I never heard the phrase before the ROPA conference, but I heard the phrase throughout the week and was quite taken aback by hearing descriptions of what we were doing that have no relation to what’s in our contract.

Memphis Orchestra musicians have felt disapproval from colleagues across the country. One MSO musician was contacted by a Detroit musician who related to the local, and then to me, that Detroit’s management was using Memphis to convince the Detroit musicians to accept service exchange. I immediately emailed Bruce Ridge, Chair of ICSOM, to help me get in touch with musicians in Detroit. I spoke with one and I think we were able to make progress in understanding each others’ takes, but theirs is a difficult situation – we decided to agree to disagree about the implications of our activities in Memphis.

The musicians in Memphis are supportive of the musicians in Detroit, and service conversion is not an accurate description of what we do here. Our normal contracted time is not to be used for community outreach. The definition of a service is the same that it’s always been. Musicians can earn extra money by doing this extra work, and funding is coming from grants that we otherwise wouldn’t be getting, or the specific project is designed to make a profit.

Please explain how payment for these community outreach activities was handled at the beginning, and now.

Both Leading from Every Chair and the Soulsville Charter School mentoring programs came out of a grant from the Mellon Foundation that facilitated cross-constituent dialogues during 2006-2007. Eric Booth came in and we had several meetings with musicians, staff, board, and community members to discuss what the Memphis Symphony means to the community, and what we could do as an organization to broaden our reach.

Those discussions led to the Soulsville and Leading from Every Chair projects. We launched those in the fall of 2007 after creating a side letter to our CBA [collective bargaining agreement]. Musicians applied to be part of either or both of the programs in the fall of 2007, and both have continued to be integral parts of our community engagement efforts.

It’s important to state that we did this in a side letter first because it was year 3 of a 3-year CBA that saw raises in every season. Our raise in 2007-08 was 8%. We also expanded the core orchestra by 2, up to 36. It’s crucial for our colleagues to know that this work is optional, and we did receive base scale increases, so our initial agreement to allow for this optional work was not the result of a concessionary bargaining situation.

Since then, we negotiated language into our CBA for the 2008-09 season to codify how all this works, and subsequent CBAs have refined this language. All musicians earn a base wage, and then musicians can opt in to the optional work. We had two 1-year contracts, and we now have a 2-year contract, so since the initial side letter we have had three rounds of bargaining to work together to improve how we administer these programs.

How did the Memphis Model myth get started?

It happened at a conference held in Ann Arbor – Ryan [Fleur, President and CEO] was there as a panelist. From the reports I read, he misrepresented what we’re doing. He said that we negotiated pay cuts for musicians but the full-time musicians could make it back by opting into this extra work. His statement ignored the fact that they were doing these extra projects prior to the cutbacks.

We did take a 10% pay cut in 2009-10, but Ryan’s math didn’t add up because musicians who were already doing this extra work could not make up the difference.

He was trying to argue that communities do not value live orchestral music the way they once did, and by expanding the role of musicians you can increase the value of the orchestra, but in so doing observers seemed to interpret our activities as being service exchange.

What is your response?

Orchestras do need to find creative ways to engage with their communities and develop new audiences. Audience development is part of the reason that we do this – the challenge is getting new people in the door for the first time. Once they experience it, they think it’s pretty cool and it’s easy to get them back. We’re trying to do this in a way that makes sense for us, that explores new ways to introduce people to what we do so that we not only provide new and valuable community service but also pique people’s curiosity about what we do in the concert hall.

People keep citing Michael Kaiser with good reason – good programming with effective marketing makes sense.

Opus One and the new season with our new music director Mei-Ann Chen bear this out. Attendance is up, people are excited about our new series, and there’s a natural growth in audiences. Memphis has the capability of supporting more than a 36 musician core with an annual budget of $4 million; it can and should be significantly larger than that. How do we grow that? It’s not all going to come through programming if we are going to maximize our growth potential. So the question is how do we reach a broader constituency? If we do this right, then our audience grows, which leads to financial and artistic growth.

The intimate contacts people get with musicians with our community engagement programs are special – they make it easier to convince them to come to concerts. We aim to give people a personal connection to the musicians, and that kind of connection makes for a more rewarding experience when they come to see us in the concert hall.

Explain how MSO musicians are compensated for extra work.

Core musicians are paid an additional salary using a formula that is based on scales in the CBA. Per-service musicians are paid an hourly wage based on the principal service scale.

Management initially proposed that these services be handled outside our CBA. In practice, they could have done so – musicians have historically been hired to perform tasks ranging from management positions to bus monitors for run-outs, all outside of the CBA and on individually-negotiated terms. That they wanted the orchestra committee and local involved from the beginning opened the door for a good faith discussion.

We wanted these to fall under our contract terms to ensure that musicians had union protection, initially because this was experimental and we wanted to make sure that participants didn’t get screwed and so we could have some oversight – we had all the same concerns that our colleagues in other orchestras have expressed, and subsequently because it just made sense. Another reason is that additional wages paid to musicians under the terms of a CBA mean increased revenue to the local to help give us a stronger voice, as well as increased pension contributions.

How would you sum up?

There is a perception out there that MSO musicians are doing office work. Last season, there was a category of optional services that read like it could be office work, but it didn’t turn out that way, and we got rid of it in contract negotiations last fall.

Joe Horowitz, an orchestra consultant, declared on his blog that we were the shining example of orchestras across the country in leading the way for service conversion. The term implies taking one form of service and converting it to another. The musicians in Memphis have been adamant in every negotiation that our normal orchestral services not undergo a change of definition. So nothing has been converted.

We as an institution looked over the cliff into the abyss of having to close up shop, and no one wanted to take that last step over the edge. Instead, we have looked at what we mean to Memphis and how we ensure that great orchestral music remains a vital part of this city’s musical landscape. This has meant improving the quality of our performances, experimenting with new and exciting programming, and finding new ways to use our talents to do a better job of reaching new audiences.

Lisa Dixon, former Chief Operating Officer

Lisa Dixon was Chief Operating Officer at the Memphis Symphony until leaving last summer to take the Executive Director position with the Portland Symphony in Maine. I met Lisa in 2008 in Denver at the League of American Orchestras’ conference; she and Gaylon Patterson, MSO violinist, were attending the conference with Anita Angelacci, Project Manager at FedEx, to explain their new endeavor, Leading from Every Chair®.

The Leading from Every Chair workshop is in two parts: the morning session introduces the participants to the conductor and to the groups within the orchestra. The afternoon is a full core orchestra rehearsal, which serves as a model for communication and team work.

Ann Drinan: Both of you were integrally involved in creating all these extra community activities – how did it all start?

Lisa Dixon: The process was organic and evolved over a number of years with a lot of hard work as we continually evolved, based on what the current organizational and community needs were.

For example, with Opus One, the goal was to increase musician engagement and ownership by creating opportunities for the talents of our musicians to shine and really connect in the community. The staff was there to actively support the musician-led project; the goal was never to have musicians replacing staff.

Opus One bubbled up out of the financial crisis – we reduced the number of concert programs due to financial constraints at the time. This opened up weeks of time where we were paying for the core orchestra to not play. At the same time we had cut the staff from 18 to 13 – so had very reduced back office support. Susanna [Perry Gilmore, see page 5] and her colleagues came up with this brilliant idea – what if we had this musician-led concert series? “We really want to run this and run with this.”

It sure has evolved even further.

As musicians were interested in things, we got it off the ground. But now musicians come to the staff with projects. One might say, “I love working with special needs kids; how can I figure out a project?” The goal is to find the right intersection of things that are artistically engaging for the musicians as well as the audience/ community – to meet a community need. The third piece is the financial element – how can we fund it?

Gaylon Patterson: The seeds for the MSO’s culture change were sown in a year-long strategic planning process that involved many people from the orchestra’s constituent groups. This wasn’t your usual weekend retreat that produces a nice growth plan that’s never seen again after it hits the shelf, but a deep exploration of the orchestra’s strengths and its limitations, given its specific location and market challenges. The musicians of the orchestra are smart, talented, highly educated and trained, and extraordinarily creative, but we were only using a fraction of that potential resource by constraining their creativity to music alone. There are also not enough of us employed full-time as musicians, and we needed to figure out some ways to expand our work to sustainably support growth.

From the planning process grew an organization-wide commitment to creative development, collaboration both within and outside the MSO, and nurturing of creative ideas. The first new collaborations were the Soulsville mentoring partnership and Leading from Every Chair, but there’s a long list of musician-driven projects in development that deepen our connections to our unique city in artistically satisfying ways. We’ve become a sort of incubator for artistic entrepreneurship. For me, it’s all about connection, and the most authentic connections come from musicians’ ideas. That’s where the authenticity comes from, and when the connection is real and true, it’s on fire.

We just received a substantial Mellon grant for $550,000 over three years – community outreach things and to help us market Leading from Every Chair and additional compensation for community programs for musicians.

How did Leading from Every Chair start?

LD: Leading from Every Chair came out of the New Strategies Lab grant from Mellon. Consultant Eric Booth led two Memphis-based meetings before we went to Princeton for the lab. We had a team of staff, board, and musicians looking at how to create meaningful partnerships in the community. We invited four different community organizations to partner with us. FedEx and Soulsville Charter School were the two organizations that traveled to Princeton with us.

We outlined what things the symphony did really well – what was at the heart of who we are, and then listened to Anita Angelacci from FedEx talking about their key challenges, core values, what they were working on. We put lots of big post-it notes on the wall with ideas, and examined them to see where the overlap was. Of all these priorities, we identified which ones seemed the most promising. Jennifer Puckett (MSO principal violist) and Joey Salvalaggio (MSO principal oboist) were our two primary musicians who helped in this critical development phase. Once we returned to Memphis, we formed a work team to get it rolling, and started conversations with other musicians and the union to figure out how to get some of these untraditional ideas off the ground.

But what sparked the concept of Leading from Every Chair?

LD: FedEx had two big needs: talent retention and leadership development – they could attract people to Memphis but they had trouble keeping them there. Leadership development is inherent in the model of an orchestra. But the program also had the advantage that those managers who went through this experience, ended up with a personal connection with a local arts organization.

7 or 8 musicians facilitate Leading from Every Chair in the morning. They also have a role in the afternoon with the full orchestra portion.

Soulsville has a different goal – it’s about mentoring through music. It’s not about trying to produce a bunch of Juilliard grads!

Lisa, how would you sum up the early days of starting all these projects?

Neal Shaffer, Gaylon Patterson and Heather Trussell performing in an Opus One concert at The Warehouse, May 2010

LD:The most important element was the fact that the musicians were involved as equal partners from the very beginning. It was a real shift – historically musicians were generally brought in later down the road once an idea had been formed. The ingredients that changed things were involvement from the very first day, and all discussions and decisions, especially around new projects, were made by a group with all three constituents [staff, musicians, board] involved. There was also a high degree of communication. We needed to make sure there communication was strong, because the rest of the organization needed to be brought along as the ideas evolved.

Gaylon, what impact have these new community engagement activities had on the way the symphony is perceived in Memphis?

GP: I’m convinced that our orchestra, in our city, has to develop broad, deep connections with our community if we’re going to grow and thrive. I would love it if it were possible to do that by putting 40 weeks a year of traditional classical programming on stage, but we simply don’t have the audience. It’s sometimes hard to balance maintaining artistic integrity at the highest level with devoting enough time and creative energy to other project development, but it’s also energizing to learn new skills. We’re not the same orchestra we were ten years ago, true, but we’re much more profoundly and directly connected with our city, and Memphis knows who we are.

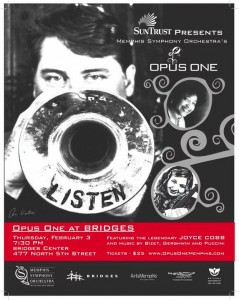

Opus One

Opus One is a new series for the Memphis Symphony, started in 2009, where the musicians perform with a well-known Memphis musician, such as alternative Rock & Roller Harlan T. Bobo and jazz vocalist Joyce Cobb, in an unusual and casual setting, usually in the round, with no conductor. The concerts enable the musicians to show off their many talents, partner with a local celebrity, and bring in a much younger audience that rarely attends their formal concerts at Cannon Center for the Performing Arts. The past four Opus One concerts have been sold out.

Click here to see the Memphis musicians Facebook page about Opus One.

Susanna Perry Gilmore

Ann Drinan: I hear you were the creative genius behind Opus One. Tell me how it got started.

Susanna Perry Gilmore: I guess I was ground zero for the Memphis Symphony Musicians Presents: Opus One. However, by mid-way through our first season, more than half of the core had opted in to organizing the project.

When the recession hit Memphis, management cut all our series to save money. We had no resident conductor, we lost 1/3 of the staff, and the grim truth is that it was cheaper to let the musicians sit at home than perform. The reduced season left us with copious amounts of unused services and an overwhelmed staff. It felt like a slow death.

Opus One came out of a climate of musician involvement that had been developing over the past six years. It’s basically a way for us to make lemonade out of lemons, and we’re learning a lot about communication: musician to musician, musicians to audience, and musicians to staff.

How involved were the musicians in putting on the events?

We did put in a lot of legwork the first season because no one on the staff had the capacity to do this, since they’d had major cutbacks. We scouted out alternative venues, approached local celebrity artists, designed the idea of a party/concert/event where there is food & drink, no stage, musicians speak between pieces, we dress informally, and the audience is wrapped around the musicians. We’re de-mystifying the concert experience; the people are nuts for it – they want us to do more. And it’s becoming a true creative outlet for the musicians.

Those who have partnered with staff liaisons are learning tremendous amounts about what is involved in concert production – how to write a press release or contribute creative ideas about poster design for branding, how the series should look, interviewing caterers, what’s the mood of this concert and how does that translate into the right kind of food. The fact that the musicians are involved in the creative control of this product is creating a tremendous sense of ownership that is so unusual in the symphony culture. It’s having a profound impact on how we interact with the staff; because we’re working together as a team it’s harder to make our interactions combative when there’s so much more education involved, on both sides. The staff have new and deepened relationships with musicians; it’s great for them to see us rolling up our sleeves and wanting to make the organization successful.

Describe some of the concerts you’ve put on.

The first show we did just used the symphony players and performed Bach, Beethoven and Big Band in an abandoned bank lobby in the heart of downtown. The next one featured a local blues singer/songwriter, Susan Marshall, in a remodeled warehouse that used to be a post office in the downtown art district that is now a private home. The strings played Grieg, the winds played Strauss, and the brass played Tomasi before we joined up with the guest artist.

This fall we featured a Rock & Roll alternative musician named Harlan T. Bobo, and we also played Handel and Hendrix, all in a bar. The February concert we just performed featured a jazz singer – we composed new jazz versions of opera arias. This spring we’ll collaborate with Amy LaVere, a local folk singer.

Artists and organizations are crawling out of the woodwork to do collaborations, to try to capture the buzz. Memphis is such a big music town that there is a lot of depth to collaborate with, and the Opus One series is having an effect on the community’s perception of us. When we do something really unexpected, it has such a positive affect on the image of the orchestra – it’s rebranding us, coolifying us, hipifying us. We even wear jeans!

What sorts of things do the musicians do, now that the staff is doing a lot of the concert production?

I have a finger in a lot of pots, making sure balls don’t get dropped. I help with the steering committee, planning for next season, and I’m tracking different organizing areas.

One musician partners with the PR department and works on the brochure and our Facebook page. Two musicians are involved with hospitality, dealing with the caterers and alcohol donations. Two musicians are working with the production staff to communicate what we need at each venue. Gaylon [Patterson] is our internal communications guy; he relays decisions to all pertinent parties.

Who is funding the Opus One concerts?

We got new money from SunTrust Bank to sponsor this series, as well as from Northwestern Mutual and FedEx. Three new people under the age of 45 joined the symphony board because of this series. There’s a lot of local buzz about it. It’s turning out to be a successful, positive, learning venture, and it’s led our orchestra to invest even more deeply in the musicians.

I didn’t see anything about Opus One on the MSO website.

We’ve been promoting it mostly through Facebook and viral media. And posters around town. We’re moving towards making it more part of the regular MSO season. We had two official Opus One concerts last spring, and are doing three this year. We’re planning next season and hope to do four plus a family concert.

What other types of new ventures are the musicians undertaking?

The Artist Growth Initiative, with new grant funding, was announced in early February. This will fund employee development for musicians. For example, our timpanist, Frank Schaffer, is doing drum circles in the community [see page 8] – it’s his idea and he’s owning the idea.

Several musicians who are also talented composers and arrangers are partnering with MSO musicians and the Chamber of Commerce in supporting local businesses by creating advertising soundtracks. We’re opening up a culture where musicians can self-identify ways they want to grow – both on their instrument and in related ways. We’ve had small professional development grants in the past, and several musicians have used them. For example, a bassoonist used such a grant to study Baroque bassoon, and a trumpeter went to a valveless trumpet summer festival. We’ve reached the point where the payoff is really becoming evident, externally, to granting organizations. It’s starting to really work for our orchestra here.

Do you think other orchestras can take what you’ve done and make it work?

It’s important to think about reinvention, as orchestras get increasingly worried about their future. It’s tempting to say, “Here’s a model and it’s good/bad,” but you must assess each one as a new case. What we have in Memphis is a natural evolution over many years.

What do you see as near-term growth for the MSO?

My personal hope is that we’ll get a new education and community outreach manager to manage this “octopus” – this is the only way we’ll ever grow the core orchestra here. We’ve been a 36-member core forever. It’s my 14th year with the orchestra and there’s been no change. It’s very frustrating for many reasons.

We’re not going to drastically grow our subscription series – we’ve reached capacity. Especially in Memphis where the symphony is not viewed as part of its real musical heritage. So, to grow the core we must use these community-related services. As we pull in new funding for this creative development of players, the core is quickly reaching capacity with preparing for regular concerts, and planning and preparing for new projects. I am very hopeful that this new funding will start being directed at part-time players, to increase their salaries and make them feel more a part of the orchestra. The part-timers get no benefits; they’re paid per service under either an A or B contract – they make about 1/3 of what the core musicians are paid.

Do all the MSO musicians feel as positive about these new endeavors as you do?

That’s a huge question – what is a symphony player? Are we redefining what is the role of a classical musician in an orchestra? Yes. Do we all like it? No. I believe that, living in this place, this is the reality – to survive as a non-profit arts organization with our small budget, we must think outside the box.

10% of the core musicians don’t like the new stuff – this is based on an internal survey. We did one mostly about Opus One, and then again in the last week. It’s not generational – our timpanist loves Opus One. The world has changed around us, and we have to adapt or die. Some percentage of musicians want to show up prepared, rehearse, and play the concert, and not be involved in the opt-in organizational stuff. However, everyone plays the Opus One concerts – it is a funded series and part of the contract. Leading from Every Chair is also a service, but they don’t have to lead the workshop in the morning. The morning is paid extra, the afternoon is a full orchestra rehearsal.

Which activities involve the extra contracts?

Opt-in contracts are for mentoring at Soulsville, helping to run the morning Leading from Every Chair workshops/leadership training, and Opus One planning. Other things as well – a few musicians are helping create a database of band charts broadcast back in 1930s – there’s a whole list of ways that musicians can choose to help the organization.

A large percentage of musicians find this exciting and creative, some are just resigned to it, and a few are actively mad about it.

But our situation seemed so dicey economically in the past few years that musicians were willing to accept things so that they could get a paycheck.

Rhonda Causie

Director of Grants and Innovations

Ann Drinan: How long have you been with the MSO?

Rhonda Causie: I’ve been with the symphony for 6 years – my job is all about making change. I was brought in because Ryan [Fleur]’s vision was to be deliberate about how to develop projects and acquire grants.

What’s your background?

I was a business writer, working on process engineering for various businesses. I wrote training books for manufacturing companies, process documents, and major proposals for a federal contractor.

Working as a grant writer for a symphony seems like a very different job.

The symphony is exciting to write about because we have a compelling story to tell.

I look at the organization in various ways, so when the musicians have an idea about a project, I’m the troubleshooter and vetter. I go through the process of determining whether it will work and create a logic model, so I know what we’ll invest in it, both short term and long term.

A musician will come to me and say, “This is what I’m thinking about doing.” Then I ask how would we look at this if it were fundable – we cannot do anything unless we know how we’re going to pay for it. Frank Shaffer, our timpanist [see page 8] wanted to work in music therapy and decided on drum circles. We talked about what he wanted to do and where in our city would that have great meaning from an impact and fundability viewpoint. We identified a partner, found a corporate foundation that would fund it, and shaped it so that his vision could be fulfilled.

I hear that your title is Director of Grants and Innovations. That’s amazing!

My title came about because of the role I play with the staff and musicians. Unlike most grant writers, I don’t work in the Development Department. In any event, we call that Patron Engagement, which includes the functions of both marketing and development. Our customer-service oriented business model is unique. I work directly for Ryan, the President.

Originally I wrote grants in the traditional sense. But the more I was brought in to a project so I knew what and where the thinking was, I would walk away with an understanding that informs what I can do in the future. I need to know what we’re doing across the organization.

How would you describe working with the musicians on a proposed project?

I have never been the musicians’ boss in any way, so there’s a lot of trust; they don’t see me as “Management.” So the musicians are very candid with me – and if I don’t think something is feasible, they believe me.

The musicians also take the time to teach me things, so I can qualify what I think I know. And I listen to what they say.

We have a mutual desire to succeed. I want these musicians in my city, and they can’t stay if we can’t pay them. We need to find some way to make it work. They bring so much vitality and quality to my community.

Tell me about starting Opus One.

Opus One – May of 2009 – what a great idea! We’re a city of music but most of Memphis is not about orchestral music. The population is 70% people of color, including the suburbs, and they don’t grow up with a tradition of western musical culture. We need to develop products to attract a different audience but nothing had ever embarked on it the way Susanna [Perry Gilmore, see page 6] described. It was groovy, and “cool” to attract a young audience. She wanted to find ways to help musicians play together in a more rich and meaningful way.

At first Ryan did not want to do it – he thought it was an expense that we could not afford. There were a lot of production costs. He told me to write a logic model and see what could result from this. So I did and everything that we hoped to happen, happened. The realizations are real. The results are real. In the short term, every goal was fulfilled. Also in the mid-term, and even the long term. And we now have three new young board members with means!

When Ryan saw the commitment, he let me pursue it. Based on our relationship with Mellon (Ryan was in their leadership program and we were one of the orchestras chosen for their New Strategies Lab), they gave us a $40,000 planning grant. The steering group went to New York City to check out Orpheus, observe a non-traditional music experience, which was Gil Shaham performing at Le Poisson Rouge, and determine the kind of music to be performed by Opus One.

We chose Eric Booth to be our consultant to help develop some of the communication systems for the musicians to talk to one another in designing the series, and he helped lead a vote about some contractual rules they chose to waive as well as some basic marketing. We didn’t spend all the money in the line items I had budgeted for the Mellon because the members of the steering committee were so thrifty!

Once Opus One got started, we had a staff member who began developing a group of supporters, so we got sponsorships.

How do you get funding for other projects the musicians want to do?

Well, the United Way paid for a scholarship grant for Frank Shaffer to go to Princeton for training for the pilot year of drum circles at Youth Villages. They are the most challenged group of kids in the community – very much at risk. We could see how well it worked, including the mentors and mentees. And another local foundation, the Grizzlies [Memphis’ NBA team] are interested in supporting this because they very much believe in mentoring, such as Boys & Girls clubs.

International Paper was another. We needed special equipment for the drum circle project. They are deeply invested in Youth Villages, and when they learned that we would be providing service to this organization, they gave us $6,000 to buy the drums.

When a musician wants to try something, if s/he needs training, or needs special skills or equipment, I must help them accomplish that and position them to succeed. If Frank can benefit by doing a drum circle elsewhere, say for a corporation, that’s great.

What other types of projects are MSO musicians pursuing?

Performances at nursing homes – this is just beginning. This is for people who have no means to pay to attend concerts.

Compositions and arrangements. The Chamber of Commerce decided to do the Sound Project and they picked eight local businesses to showcase. The hired MSO musicians to compose and perform a 5-minute infomercial. One of the composers is interested in getting Sibelius [software package] so he can continue this – the MSO can buy this program for him with their funding and enable him to use it. If he were commissioned to write something outside of MSO, it would be fine to use Sibelius for this other project.

There’s a professional broker whose father is a retired physician in Memphis. His circle of friends know about classical music, but he doesn’t. So the son has asked the MSO to develop a music learning program for his father. Two musicians are developing a music appreciation course for this man, and he pays for their time and for ensembles to visit his father in his home.

Some musicians are mentoring at Soulsville [see page 7] and are also mentoring in a few public schools, as well as orchestra students in arts magnet schools, both middle and high school.

We have a musician who does a radio hour every week on our public radio station. The MSO Radio Hour. She highlights the music that’s coming up in our concerts, as well as our community work.

Memphis has a grand old hotel, the Peabody Hotel [with the ducks in the lobby], where jazz music was played. All those charts got sent to the public library in Memphis, and that library was torn down when a new facility was built. They called the MSO and our librarian went to take a look. They had 6,000 charts of fabulous swing orchestra music. Two musicians are working in our library digitizing, organizing, and cataloging those charts. This is the closest we have to any musician doing office work.

What about the future?

We’re building a demand for our product.

We are going to hire an aesthetic designer to figure out ways to incorporate our community project work into our concerts, either before or at intermission. We want to showcase the work of our musicians so that it is celebrated and they get the acknowledgment they deserve in the hall. We’re trying different things – and the community wants these different things. We must be elegant and sophisticated, and find new ways to do it. For example, we might have photos of musicians playing at a nursing home, and invite the family members of these nursing home residents to the concert.

Soulsville

An Interview with Frank Shaffer and Jennifer Puckett

Soulsville Charter School, which opened in 2005, provides a day-long, academically rigorous, college preparatory education focused on instilling each child with the thinking skills, work ethic, and appreciation for learning that s/he will need to succeed in the world. The Soulsville Charter School started as a middle school but is expanding, one grade a year, to include a high school. The school’s mission statement is impressive: “The Soulsville Charter School will produce students who will be able to read, communicate effectively and possess high-order thinking skills through the interconnectedness of academics and music. Influenced by our heritage, community legacy and our organization’s existing culture of innovation, creativity and success, we will engage our students in unique and creative enrichment activities and projects that reinforce core academic areas.”

Several MSO musicians have been mentoring students at Soulsville Charter School since the fall of 2007. The program began with six MSO musicians mentoring 8th grade students, and was expanded to 12 MSO musicians mentoring 3 grade levels.

Frank Shaffer, Timpanist, was one of the first musicians involved with Soulsville.

Frank Shaffer: The Soulsville school is based on the KIPP model, such as the KIPP school in Brooklyn. It’s a charter school for kids who are having trouble in other schools with their behavior, grades, etc., and it’s primarily African-American. Part of the school day program includes a music period every day, where all students are expected to participate. They have a string orchestra with a rhythm section – electric bass, guitar, keyboard, and a percussion section of 3 marimbas. They have two percussionists, and a string orchestra at every grade level. I started out teaching 8th graders.

Soulsville started as a charter middle school, but they are now building a new school on the site of the old Stax recording studio to create a high school. The Stax Music Academy was next door with an extensive after school program, which gave the Soulsville Foundation the idea of starting a charter school.

Jennifer Puckett, Principal Violist, has taught violin and viola at Soulsville. She is now mentoring at Overton and Colonial schools, which is a new mentoring program started this year. These schools are in East Memphis and are also primarily African-American.

Ann Drinan: How would you describe your experience at Soulsville?

Jennifer Puckett: It started out as a mentor program, where 10 or 12 MSO musicians would go almost every week – 15 times during the year. This is definitely an opt in situation for the musicians – it’s not required.

We go during the students’ regular day-time class time, and divide up the kids so that each musician has from 8 to 12 kids. We spend about an hour with the kids – sometimes 90 minutes. We teach violin, viola, cello, electric guitar and bass, and marimba, and we give one concert each semester, which is a big event for the whole school. I played along with them the first year.

What do you think makes the musicians decide to do this? At the Baltimore Symphony’s OrchKids school, only 1 BSO musician is involved.

You need a passion for teaching, which I have. I am thrilled with this project, and it lets me make a little extra money. At Soulsville it’s really important to teach the students music but also to be a person that they can look up to. It’s more the human side of it than the music side of it. It’s really important for them to have this person in their life whom they can count on to be there every week. The MSO is planning a side-by-side this year in February with the Soulsville students.

It’s also a very serious music program – the students have orchestra every day as a class. Some of the MSO mentors come every day, which makes it a nice break for the students from their regular teacher.

The Soulsville kids really love our coming – it has touched their lives in some way and that makes me feel good.

Drum Circles

An Interview with Frank Shaffer, Timpanist

Frank Shaffer, MSO Timpanist, has started leading drum circles as part of the MSO community engagement program.

Ann Drinan: What brought you to Memphis?

Frank Shaffer: I came to Memphis back in the 1970s from New Haven, where I got a graduate degree from Yale. The orchestra was only part-time back then, and I taught full-time at the University of Memphis. I’ve been doing both – teaching and playing all these years.

What’s your feeling about the community engagement model in Memphis?

The new model is a very good one. There are a few problems with it as far as the traditional orchestral musician is concerned, and I understand and support their concerns, but I’m not a person in that mold.

Many orchestra players who come to Memphis don’t have a lot of teaching experience. The Memphis model tries to find ways to accommodate all the different folks in the orchestra – half the musicians are teachers also, and half are primarily performers who may teach a few students. So we offer a large variety of projects that are innovative and that have increased our community visibility, which will hopefully have the community shoot more money our way. We’re doing very well in the grants department.

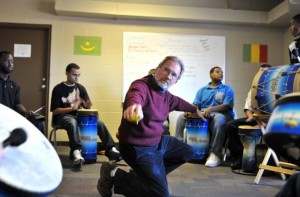

Tell me about the drum circles you lead.

The REMO drum company, founded by Remo Belli, make drum heads and world percussion instruments from recycled wood fibers, such as particle board-type material. They’ve won the award for being the greenest manufacturing plant in California for the past 8 years.

They are in the forefront of the drum circle movement, which is intended for therapy and for individual transformation. Their program is called HealthRHYTHMS.

I went to a general training session in Princeton in the fall of 2010 (New Jersey is a big place for drum circles) with about 60 people in attendance. This first training was funded by the United Way of Greater Memphis. I went to Valentia California, along with Laurie Pyatt, an MSO violinist, for training in January, 2011; Laurie’s training was funded by International Paper. The International Paper grant also enabled the MSO to purchase drums for the sessions at Youth Villages.

What got you interested in learning about drum circles?

I am a relative newcomer to the drum circle experience, having been a professional-classically trained percussionist. Several years ago, Ed Murray, assistant principal percussionist and a colleague of mine in the Memphis Symphony, presented an Afro-Cuban clinic and drum circle at the West Tennessee Day of Percussion. While I had been aware of the drum circle movement for many years as a member of the Percussive Arts Society (PAS) Health and Wellness Committee, I had never actually experienced one. The participants had a mixture of all ability levels and musical skills, yet the result left everyone deeply satisfied and inspired. It was a great way to finish that Day of Percussion.

When PAS initiated several years of Recreational Drumming: A Celebration of Health and Wellness grants, I organized and participated in these in Memphis and observed how happy they made me and the other participants. There was really something to what they did for people, no matter what the skill level.

I’ve had some personal injuries, so I’ve been a member of the PAS Health and Wellness Committee since 1999. Through them I met Dr. Robert Friedman, a psychologist in the process of writing a second book: The Healing Power of the Drum II. He’s very active in this movement to promote drums to help people get their act together. The program involves using the healing power of the drum to help people deal with personal issues, both physical and psychological. It’s not about the music; it is about the person.

He also put me in touch with John Fitzgerald of Remo, who encouraged me to come to the Saturday night drum circle at the 2009 Percussive Arts Society International Convention, which was absolutely wonderful. I assisted in encouraging newcomers into the circle and got to see first hand all of the wonderful therapeutic benefits of drum circles: the looks of joy on peoples’ faces and the general feeling of inspiration, satisfaction and well-being that emanated from the experience.

The Memphis Symphony was looking for a way to partner in music therapy with LeBonheur Children’s Hospital in Memphis. They have an art program but no music. They approached us initially and then they backed away.

So I spoke with Rhonda Causie our grant writer [see page 6], and we did some brainstorming. Rhonda talked about being at Youth Villages – a non-profit organization that’s dedicated, 24/7, to troubled kids who are having difficulties in school and at home, sometimes accompanied by mental health and psychological issues. It’s a community campus idea that’s spreading fast throughout the south, with a strong base in Atlanta and Memphis. The kids come for up to 180 days for rehabilitation – they have counseling, regular school, and other activities. The MSO educational ensembles (string quartets, trios, woodwind and brass quintets) go play concerts, and I did some performance demos. The kids really needed hands-on experiences with music, and Rhonda thought the drum circle would be a perfect fit.

I meet with them on Saturday afternoons for about an hour. It’s a pilot project – the MSO’s is the second drum circle at Youth Villages. They already had an African Village drum program that is performance based but it’s different from HealthRHYTHMS, which is not performance based. Drumming is the vehicle for transformation and transcendence.

How would you describe HealthRYTHMS?

Here’s a description from the MSO office:

HealthRHYTHMS, a group empowerment drumming protocol sponsored by Remo, Inc., is the basis of the Memphis Symphony Drum Circle Project. Frank Shaffer has begun the Saturday drum circles at Youth Villages Bartlett campus that will continue into the spring of 2011.

Researched-based studies indicate that the HealthRHYTHMS protocol positively impacts juvenile rehabilitation. Preliminary results of the HealthRHYTHMS drum circles at Youth Villages have been very gratifying. Students are asked at the end of every session how they feel. Most say “good” or ‘great,” while others have indicated a release of negative energy and thoughts. It is interesting to note that most sessions designed to last 45 minutes usually last an hour since participants are reluctant to leave.

The great smiles on some of the student’s faces as they drum really tells the true story about what it can do for them. In the future, the MSO will offer drum circle experiences to local mentoring groups as a tool for enhancing the development of adult-to-child relationships for at-risk youth.

You really seem excited about this project.

I’m on fire about this. The protocol is designed to work with any population – mentally-challenged individuals; corporate situations with employees who are burned out or mistrustful; hospital settings, for both staff and patients; geriatric groups; at-risk populations, etc.

Most of my adult life, I have been looking for a way for ordinary people to experience the transforming power of music and the resulting transcendence that I have felt many times as a performer. I have found it in the Healing Power of the Drum through HealthRHYTHMS. I am very excited right now about being a HealthRHYTHMS facilitator, but I am also very much at peace with myself.

Again, from the MSO office:

MSO staff enjoyed several circles when the new drums arrived. Everyone had a great time, got to be creative, and most enjoyed the stress relief and sense of well being the drum circle promotes. Written comments in surveys filled out after the circles such as “wonderful experience,”“I feel stress-free,” and “fantastic” were common. Corporations that have used drum circles show happier employees, less absenteeism and burnout. Hospitals have noticed positive effects of drum circles on both patients and staff. The Memphis Symphony is looking forward to exploring all the possibilities that the Drum Circle Project can offer the community.

Tony Woodcock

President, New England Conservatory

I visited Memphis recently and sat in on a meeting of musicians and staff, discussing possible new activities. I found the musicians at the meeting thoughtful, full of finesse, energetic, and supportive. I was impressed at all these positive things attached to the way they discussed things. I know how difficult it can be for musicians in terms of change, reexamining things, doing things outside the contract, which most view as a safety blanket.

Susanna [Perry Gilmore] was leading the meeting. She was very democratic in how she said something. “If we do that, it will cost us more money – let’s find a way to be neutral” (money wise). The musicians at the meeting were very conscious of the need to not invoke the contract and to be flexible.

Symphony musicians don’t get what I experience here at the conservatory – unfettered creativity emanating from every studio that gets into the DNA of the organization. A dream on Monday can come to fruition on Friday. How does that creative attitude become the prohibitive attitude of the professional musician once s/he’s put into that institutional format? This format has its own culture which is based upon a long history and tradition that is almost impossible for one individual musician to break through. You need a critical mass to make a change in an orchestra. The same is true of boards and managements – all need to be thinking very differently.

I’m writing a piece about Detroit on my blog. The status quo is not an option. Instead of talking about relevancy all the time, we should be talking about legitimacy. It’s a much bigger and more important question. We shouldn’t be talking about great traditions and longevity – instead we should be trying to get past the orthodoxy of education programs and Music Directors and reinvent ourselves – ask some basic questions. Instead of ending up with a Detroit, everyone needs to take ownership of the problem. It does not reside in any one tier or area. Unless people are ready to come to the table with a creative mind set to problem solve (rather than to go in with baseball bats), only then will something as impossible as Detroit be prevented from happening again. We are so good at being in denial about our problems. We must be really honest and face up to them.

Click here to read Tony Woodcock’s blog post about Memphis and their community engagement activities.