Elgin Symphony Orchestra

About the Ensemble

The Elgin Symphony Orchestra is a relatively small (their budget is about $3 million) suburban orchestra northwest of Chicago, yet they recently made a Copland recording for Naxos, the city of Elgin plans to build them a new hall, and they consistently operate with balanced budgets. What makes them so successful? The ESO appears to have been able to define who they are and what works for them, and to stick to that model, despite industry trends in different directions.

Polyphonic Senior Editor Ann Drinan spoke with three orchestra principals, Charlie Schuchat, tubist and chair of the players’ committee, Bob Hanson, music director, and Michael Pastreich, executive director. In addition, at Michael’s urging, Ann interviewed Sean Stegall, Assistant City Manager, to get the city of Elgin’s perception of the role the symphony plays in the community.

Founded in 1950 by Douglas Steensland, the Elgin Symphony began as a community orchestra performing at Elgin Community College. In 1971, the role of music director passed to Margaret Hillis, the legendary founder and conductor of the Chicago Symphony Chorus and an assistant to Robert Shaw. Ms. Hillis conducted the ESO for almost 15 years, and passed the baton to the ESO’s current music director, Robert Hanson, in 1985 after he served as co-music director with Ms. Hillis for two years.

The orchestra presents over 50 concerts annually, including 8 triples (quadruples next season) of the Classic series, 3 triples (4 next season) of the Pops series, Gala and Holiday concerts, and an American music festival. Most of the concerts are presented in the 1200-seat Hemmens Theatre in Elgin; the Friday night Pops and two of the Classic series concerts are presented at the 440-seat Prairie Arts Center in Schaumburg, a neighboring city.

In addition, the ESO offers several educational programs, including in-school ensemble performances, the Petite Musique and Kidz Konzert series held at the Hemmens Theatre, the more intimate ESO Encounters series held in the Hemmens Theatre balcony, and a new 4-concert series for home-schooled children.

In the late 1990s the ESO held an endowment drive whose primary purpose was to raise the pay offered to their musicians; they were successful and became Illinois’ highest paid orchestra outside of Chicago. Consequently, many free-lance musicians living in Chicago are attracted to the Elgin Symphony – some have even settled in Elgin – and the ESO has reached a new level of musical excellence.

The story of the Elgin Symphony’s relationship with the city of Elgin, and how it manages to thrive in the shadow of the Chicago Symphony, is a fascinating one and best left to those who know it best. Read on to find the secrets of their success.

Ann Drinan, Senior Editor, May 2007

An Interview with Charlie Schuchat, Tubist and Chair of the Players’ Committee

In addition to being principal tuba (and player’s committee chair) with the Elgin Symphony Orchestra, Charlie is a member of Tower Brass, principal tuba with the Chicago Sinfonietta and the Joffrey Ballet Orchestra, and a member of the award winning Asbury Brass Quintet. He is currently a faculty member at both Northern Illinois University and the Chicago College of Performing Arts of Roosevelt University. Charlie is a native of Washington, DC and a graduate of Northwestern University, where he studied with Arnold Jacobs.

Ann Drinan: Where do your musicians come from?

Charlie Schuchat: We are a per-service orchestra about 40 miles NW of Chicago and so have a mix of players who come from the Chicagoland area, and even several players who come down from Wisconsin. There are also many active free-lancers who live in Elgin. In addition to playing with ESO, many of us also work with the other orchestras in the area, including the Chicago Sinfonietta, Lake Forest and Northwest Indiana Symphonies, and the Illinois Philharmonic, as well as Grant Park, Milwaukee Symphony, and the Chicago Symphony.

Elgin Local 48 gave up its charter in January 2006, and we are now part of Chicago Local 10-208. Many of our musicians had belonged to both locals before, and consequently Local 10-208 was very aware of our orchestra and its members.

CS: We currently play in the Hemmens Theater, a multi-purpose hall – the acoustics are not terrific and it is also not ideal for patrons or musicians. There are plans to build a new hall, which will almost certainly involve the city of Elgin. The new hall will hopefully be a concert hall with us as the principal tenant, which should let the ESO expand our season more easily. We have seed money for it and the city seems really interested,

CS: We’ve been growing, so there are a lot of challenges. Next season, we’re adding a week of Pops concerts (a 3-concert set) for a total of four weeks. We currently do 8 sets of Classical concerts (Friday and Saturday nights, and a Sunday matinee).The Sunday Matinee for our Classical concerts is the most popular, and these concerts are often sold out. Next season, because of the popularity of our Sunday matinee, we’ll also have an additional Friday Matinee on six of the weeks.

We are in the middle of a 5-year contract and negotiated an addendum to our current agreement to cover the addition of these new daytime performances. The challenge is, of course, having a performance during the day when some of our members have full-time employment. But it will also be a challenge for all of us to have two heavy classical programs separated by only a few hours. The addendum to the agreement includes the ability for Tutti players with full-time day-time employment to request to be excused from the Friday Matinee for up to three of the six Friday matinees. Non-tutti players can request to take the Friday Matinee concert off and a sub will play one rehearsal and the Friday Matinee for them. Management has to make a best effort to meet these requests.

AD: Was there a lot of resistance among the Elgin players to adding this concert?

CS: There certainly was some resistance. We did a survey of the members (using a web-site called survey monkey, which worked really well!!!). After looking over the results, the players’ committee felt we could go ahead and try to negotiate a deal. It’s a good opportunity for most players; the orchestra is growing and we want to encourage that as best we can.

We have a good absence policy. Our orchestra is not full-time so we are often trying to balance different gigs.The formula for attendance is: musicians contracted for 15 weeks (all classics, pops, holiday, gala) must play 10; musicians contracted for 14 or 13 weeks must play 9; musicians contracted for 12 weeks must play 8. Children’s concerts, which are extra, can constitute “credit” towards this minimum attendance requirement – we can in essence “put them in the bank” to count towards the number of weeks we need to fulfill our contractual obligation.

CS: Right now it is pretty healthy. It seems like there is always something but communication is pretty good between the committee and management. They do not do everything we say but we’re working on it!

The Elgin Symphony, Nathaniel Stampley, and the St. Charles Singers recording an all-Copland CD for Naxos

CS: Yes, it was the culmination of an annual festival. This year’s festival was called Copland – An American Icon; previous festivals have featured the music of Barber, Peter Boyer, and Dvorak among others. A patron wanted to help with the recording – she’s very generously underwriting it. So we worked it out with Naxos – they wanted us to do a recording session, not create the CD from a live performance.

CS: Yes, on WFMT, Chicago’s commercial classical station. We’re paid$20 per broadcast plus a re-use fee for concerts. They broadcast us once a month, but we only play eight Classical programs a season, so they use older performances in re-broadcasts for the other four months.

AD: What types of community engagement performances do you do?

CS: We do some educational concerts as chamber ensembles. We have a woodwind, a brass, and a percussion group, in addition to a few string groups. We put them together informally – they’re not mentioned in the contract except for the compensation. There are also performances in parks, and we’re also hired by the Elgin Choral Union to collaborate on their subscription series.

CS: There is so much pride in the city of Elgin to support our orchestra. We’re now a suburb of Chicago, which has a long shadow, but we are the symphony of Elgin. We’re part of the community. Elgin has not moved but the suburbs have grown to reach Elgin. The level of quality is such that a segment of the greater Chicago population prefers to drive west to Elgin than go to downtown Chicago and fight its traffic, parking, etc. The orchestra is constantly growing and improving in quality.

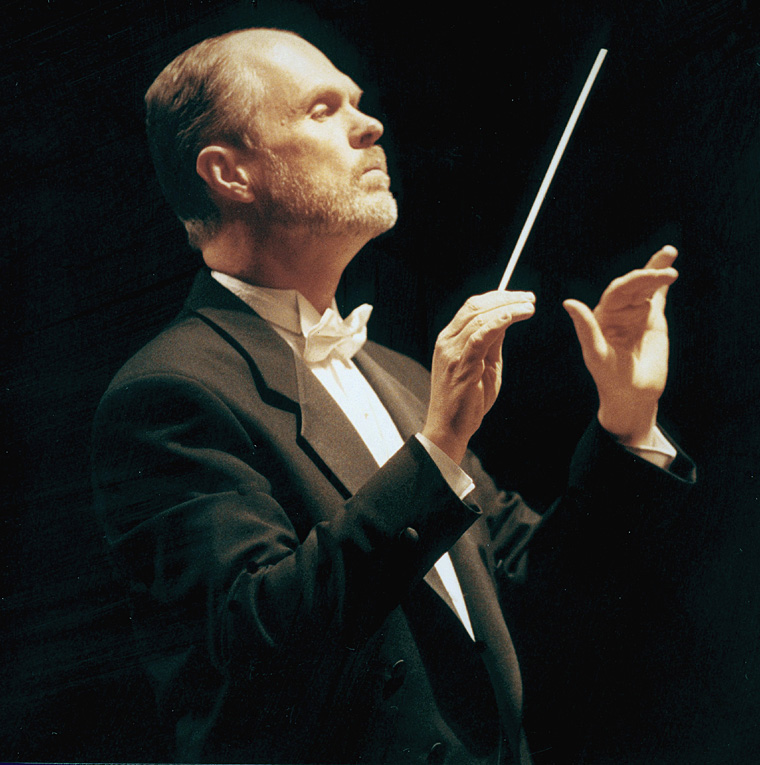

An Interview with Robert Hanson, Music Director

Robert Hanson has been music director of the Elgin Symphony Orchestra since 1985. During his tenure with the ESO, he led the organization through the process of becoming Chicago’s first professional suburban orchestra in 1985, becoming Illinois’ premier regional orchestra in 1997, and is currently leading the organization through an unprecedented growth in programming and artistic excellence. Bob is a published composer with more than 25 commissions, including Psalms of David and Hiawatha, full-length oratorios commissioned by the Elgin Choral Union, and has been music director of the Elgin Choral Union, the Lake County Chamber Orchestra, the Liberty-Fremont Chorus (IL) and the Traverse Symphony Orchestra (MI). He received his Master and Doctorate degrees in Music Composition at Northwestern University, where he won the coveted Faricy Award for excellence in music.

Ann Drinan: How would you describe the Elgin Symphony?

Bob Hanson: We’re in a pretty unique position. We’re just far enough away from Chicago – we’re 36 miles from the Loop – that we have our own identity. We’re not competing with groups in the city, but we’re close enough that we have access to all the great freelancers in Chicago. We’ve had discussions with the principal players and the players’ committee about how to grow. Should we form a core orchestra? We decided that we’re better off remaining a per-service orchestra with a somewhat flexible attendance policy because we can access world-class players who can’tafford to be tied down to the kind of commitment required of a full-time core musician.

If you compare Elgin to Kansas City or the West Coast Symphony (FL), there’s no comparison. They have no local player pool so they have to bring in everybody. In Elgin, the players are already here.

We have the advantages of being a wonderful regional orchestra that plays at a very high level, but also have the flexibility of per-service players who can adapt quickly if we need to change the season. As an example, for two years we tried a Sacred Music series but couldn’t get it off the ground. The players understood and were amenable to our removing it from the season, as it constituted extra work. Charlie Schuchat is a great players’ committee chair – he’s a good thinker, and he bases decisions on what’s good for the orchestra. Next year is the last year of a 5-year contract and we anticipate that both sides will work as a team as we build the new one.

AD: What would you consider your recent musical highlights and what plans do you have for the future?

BH: Well, the current highlight is the Copland Naxos recording we just did. One of our board members, Joyce Dlugopolski and her husband Ed, very generously underwrote the recording session – they’ve been enthusiastically supportive and sat through both sessions.

The Elgin Symphony, Nathaniel Stampley, and the St. Charles Singers recording an all-Copland CD for Naxos

We’d just finished our 3rd In Search of Our American Voice festival, which we do every year. Previous festivals featured Dvorak, early American composers such as Gottschalk – last year was immigrant composers. This year we featured Copland and performed works that were not in the Naxos catalogue; we did his Piano Concerto with Ben Pasternack, a Copland specialist. The concerto is difficult for both the pianist and the orchestra. Copland wrote it in 1926 when he was still experimenting with jazz. We also performed and recorded the Copland-sanctioned arrangements of the Old American Songs set for chorus, and the suite from The Tenderland.

AD: Tell me about the proposed new hall.

BH: There’s ahuge probability that it’s going to happen. The big issue remaining is whether it will be a multi-purpose hall or a concert hall. There is a movement afoot to try to bring Broadway to Elgin. The symphony feels that, while Broadway could be a nice thing to bring more folks to the downtown, it is difficult to mount and sell – especially since Elgin has no history of producing Broadway at any level. Elgin already has a wonderful orchestra. Why not capitalize on the orchestra by building a world-class concert hall?

AD: How would you describe the health of the ESO?

BH: Very good. Our financial position is good; we’ve had very few deficits in our entire history, and they’ve been insignificant amounts that were made up the next year. The relationship with our players is the best it’s ever been. We have some of the best principal players in the region, and we have an excellent conducting staff. Our associate conductor, Steve Squires, is excellent. Our education conductor, Randal Swiggum, who does all our educational programs including planning and conducting the concerts, taught in public schools for 12 years. We also have a very able cover conductor, Andrew Lewis, who also conducts the Elgin Choral Union.

We have great community support, and a very engaged board of directors. When I arrived in 1974, the ESO was a true community orchestra with three concerts a year, rehearsing every Thursday night whether we needed it or not! Originally the orchestra ran on the town and gown concept – it was a college orchestra but amateurs from the community played in it. In 1981, I helped form the first board of directors. Ed Brody was the first president of the board and he pulled in all the important community leaders – it was a dream board. Thus we were able to grow and become “the” regional orchestra in the state. The board is still made up of movers and shakers in the community.

I’m only the third music director in the ESO’s history – Douglas Steensland conducted from 1949 to 1971, Margaret Hillis was music director from 1971 to 1985, and me from 1983 to present (I was co-director with Margaret for two years after serving as her assistant for 9 years). We became a union orchestra in 1985. Because we’ve had only three music directors, there is a lot of musical continuity with the past.

AD: What are the current budget issues?

BH: The budget is increasing every year – when we have a new hall, there will be huge jumps in the budget. We’ll have more seats, a higher level of guest artists, etc. We’ve done very well with meeting our budgets.

AD: How would you describe the support from the community?

BH: We have phenomenal community support – there’s a loyal audience base that is so proud of the orchestra. It’s really gratifying being part of this organization. 20 years ago or so, the city hadn’t been giving us much support. Now they’re using the orchestra as an attraction for developing the downtown. There’s a major urban renewal project ongoing, with condos being built on the river, the downtown being revitalized, the largest indoor fitness center in the country, a new public library, etc. The city realizes what the symphony can bring to this revitalization by bringing in the right people. One of our board members is building a large condo complex on the river; he began coming downtown because of the symphony and saw the opportunity. Another board member is donating the land for the concert hall, close to the river.

AD: Tell me a little about Elgin.

BH: Elgin was home to the Elgin Watch factory in the mid 19th century. Borden’s Milk Company also started here. The Elgin Watch factory moved to South Carolina in the late 1950s. Elgin has diversified with other types of industries and, with Interstate 90 providing easy access to O’Hare Airport, is one of the fastest growing cities in theregion. We have the 2nd largest school district in the state, and there are about 2 million people within 30 minutes of our hall (less than 30% of subscribers come from an Elgin address). The city just annexed an area that’s twice the size of the current city.

Elgin is a full-service city with at least a 30% minority population, and it’s definitely not a suburban bedroom community. Many old-Elgin families still live in the area, and there are wonderfully-preserved historic districts with 150 year old buildings and homes.

AD: What else makes you unique?

BH: One other interesting project is that we have begun to do historically-informed performances. We call them HIP performances. For the last five years, we’ve brought in specialists in early music to work with our string players particularly to try to recreate the sounds of early music using modern instruments. We don’t want to become an early music ensemble. However, I feel full-service orchestras are losing baroque and classic period repertoire to early music groups. We must all learn to be versatile and include early music on our regular subscription concerts.

Ken Slowik from the Smithsonian – he heads their chamber music/early music program – came in two times. First, he conducted (and played harpsichord) Brandenburg V and Fireworks Music. Last year, he did Tartini’s Gamba Concerto paired with Beethoven’s Eroica. Two years ago, I paired Brandenburg 1 with Bruckner’s 6th. Krista Benion Feeney, concertmaster of Mostly Mozart and St. Luke’s in New York, came and did a play/conduct of The Four Seasons, which we paired with Beethoven’s 8th. Gonzalo Ruiz, baroque oboist, was here last year playing Mozart, and Elizabeth Blumenstock, concertmaster of the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra of San Francisco, will come next season to play Vivaldi.

We also have an on-going year-to-year project called In Search of the Great American Symphony. In this project, we systematically program at least one symphony by an American composer each season. We’re very careful in programming these American symphonies to complement our season and the concerts in which they are performed. To date we’ve performed Copland’s Third Symphony, Roy Harris’ Third Symphony, Samuel Barber’s First Symphony, Alan Hovahness’ Second Symphony, and next month we perform Leonard Bernstein’s Jeremiah Symphony. Our audiences find this an interesting way to hear 20th century American works and enjoy comparing the styles of the various composers.

An Interview with Michael Pastreich, Executive Director

Michael Pastreich became the executive director of the Elgin Symphony Orchestra in 1996. Since his arrival, Michael has worked with the community, board of directors, and musicians to build the Elgin Symphony Orchestra into Illinois’ premier regional orchestra. During his tenure, the ESO has seen tremendous increases in ticket sales, and growth in individual, foundation, and grant support. He earned his BFA in Silversmithing from Washington University. Upon graduation, he participated in the American Symphony Orchestra League’s Orchestra Management Fellowship Program.

Michael Pastreich: We are a suburban per-service orchestra that serves Northeastern Illinois. We have very clearly defined our goal as to draw the upper half of a “C” around the city of Chicago. We are not trying to penetrate into – or below –Chicago, but rather are focusing on north and west of the city.

MP: Elgin has the huge advantage of the Chicago player pool right around the corner. My observation of some other orchestras is that they try to figure out how much money they can raise, then how many tickets they can sell, and then use that money to pay the musicians as much as they can. We want to get the Chicago players on our stage and then market them. If we do both of those things – have a great orchestra playing to full houses – fundraising will be much easier.

MP: Our budget is $2.7 million this year; next year it will be $3.2 million. It’s a big jump – we’re adding a Friday matinee concert to our Classic series next year, so they’ll go from triples to quadruples, and we’re adding an extra week to our Pops series.

In the last nine years, we’ve had one planned deficit and one unplanned deficit. The planned one was when decided to stick with adding a seventh week of Classics concerts in 2002, despite 9-11. The unplanned one was two years ago, and was almost 2% of budget. On the other hand, we’ve never had a large surplus either. We’re not flashy – we stick to our knitting in a very disciplined manner. We don’t do projects that attract great foundation support, nor do we reinvent the wheel or redefine what a symphony is. We try to understand how the book was written and we stick to it.

AD: What are your recent musical highlights and what plans do you have for the future?

MP: Well, we just finished a great Copland festival, and we’ll perform Mahler 5 next year. During my tenure, the highlights started when our general playing took a great leap forward during the 1999-2000 season. Since then, we have had everything from our first state tour in 2000 to our first Naxos recording last week.

AD: How do you harness the Chicago free-lance player pool?

MP: The City of Elgin incorporated just a couple of years after Chicago – Elgin was the economic center for a large agricultural area. A decade ago, the suburbs of Chicago hit Elgin, so it’s the best of all worlds: people are used to coming to us, we can tap the Chicago bedroom communities, and we have the Chicago player pool just around the corner.

Given this ideal set of circumstances, we needed to decide how best to format our orchestra. I believe we need to stay a per-service orchestra. At the same time,musicians I really respect have discussed the need to move towards becoming a full-time orchestra. It’s important for the musicians and management to agree on which direction to go, so we sat down and had a series of discussions on the topic.

1) megas (New York, Cleveland, Chicago)

2) orchestras that need to get the best musicians in the area

3) orchestras that need musicians to move to their areas

The two models we discussed were the Dayton Philharmonic and Orange County’s Pacific Symphony. Both are well-run, financially-healthy organizations whose musicianship is improving; so growth and wisdom are not the issues. Dayton seems to be pushing toward becoming full-time; their attendance policy and how they pay their musicians reflects this. From what I can see, Pacific says, “We’re the nation’s biggest per-service orchestra and we’re going to stay that way.”

Elgin is a per-service orchestra – we’re paying for what we need. At the same time, our musicians can take whatever job is best for them because we’ve loosened the attendance policy. We work at making sure we’re where the musicians want to play. Before 1997, we had a much tighter attendance policy, but we have much better attendance now – we were always making exceptions for our best players back then. We’ve aggressively tried to become the best paying gig in terms of pay per service and the number of services; we work hard to treat the musicians well; and we try to be sure the staff who interact with the musicians understand why we are here.

In the end, I think we came to consensus – if not agreement – that the per-service model worked best for all of us.

Another way to look at it is that a decade ago, we were one of many suburban orchestras – a lot of Elgin community members were in the orchestra. Then in the late 1990s, we embarked on an endowment drive whose primary purpose was to raise the pay for musicians. We then actively tried to get the best musicians from Chicago’s free-lance pool.

Since then, many of our Chicago free-lancers have moved to Elgin. They can afford to buy houses in Elgin, so they do the reverse commute into Chicago for their free-lance jobs.

AD: Tell me about your plans to build a new hall.

MP: The challenge we’re facing is that we’re in a building, The Hemmens Cultural Center, which was built 40 years ago and which was built just to get it up – it was not meant to be a building that would last forever.

When Hattie Hemmens died in the mid 1960s, Elgin was at an all-time low. The Elgin Watch factory had just closed and the city had very little money. She left money to build a community center, but did not leave enough money, so the city had to cobble together enough money to cover the balance. They then ran into all sorts of underground water problems and had to value engineer as much money out of the building as possible. Now, 40 years later, it’s not lasting. We’re faced with the potential crisis of not having a viable building 15 years from now.

- a concert hall, which is meant for an orchestra to perform in.

- a fly-tower, where you can have first-run Broadway shows.

- in the middle – a flexible space with the ceiling, floors, walls, and audience rake of a concert hall, but that has a variety of flexible features so that many different things can happen on the stage.

A concert hall is unlikely for us – the current debate is between options 2 and 3.

A flexible space has the ability to do everything currently done in Hemmens but with much better sound. It would be different from the other halls in the region, but you wouldn’t be able to have Broadway.

The Elgin Symphony, Nathaniel Stampley, and the St. Charles Singers recording an all-Copland CD for Naxos

We need to figure out how much it will cost – we’re early in those negotiations. The city might build the building and we might raise an endowment to cover part of the subsidy of the building, perhaps the difference between the current subsidy of Hemmens and the future subsidy of a new building. We might also raise money to add niceties to the building, such as changing cement finishes to wood or granite.

AD: How did you decide the amount of money you were capable of raising for this project?

MP: We sat down with a group of community leaders and talked to them about what Bob [Hanson] saw as top priorities for the orchestra. They ultimately decided that we needed to build a new hall. We made it clear that they were the ones who had to make it possible. We came out of it with a group of individuals intent on building the hall. Over a 6-month period, we decided we were going to raise $5 million – all we had were some drawings of what the building might look like. We succeeded; six gifts made up the $5 million, and only one person said no.

MP: We had a really tough negotiation in 2000 – when we came out of it, we tried to figure out what the root cause was. One of the things we identified is that we weren’t an orchestra but rather were a bunch of freelancers coming in for a gig. We had to figure out how to become an orchestra. We’ve started feeding the musicians between services, and have asked the staff and board to join the musicians, to build a sense of a team. Dinners between services, parties, and other social gatherings for the musicians to spend time together have certainly helped improve relations. We now also involve the musicians as true partners in both long-range and artistic planning. I think they feel like they are now a part of the solution.

AD: What makes Elgin unique?

MP: When I first arrived,Bob and I made a list of 7 points about how to run the ESO. We decided not be competitive for audience but to be deeply competitive for musicians. We don’t want to compete with the Chicago Symphony – if we do a good job of presenting and marketing the concert, people will come. Where we really shine is when you look at our long-term tracking – we remain financially healthy, subscriber numbers grow, the quality of our musicians grows, and the number of concerts grows.

But how do we differentiate ourselves in the Chicago market? Bob and I spent a lot of time discussing that issue. I have never asked them, but our read is that the Chicago Symphony didn’t want to become a museum piece, so they played a lot of new music. The Chicago Sinfonietta is a cool, funky orchestra that does pipa and tap dance concertos, and is very good at getting multi-ethnicity on stage and in the audience. Music of the Baroque does music from the Baroque era. Bob and I decided to play music that people like. It’s a missionary view – some of our staff has been frustrated that we’re not pushing the envelope. But we want people who don’t know much about classical music to leave thinking that they really like classical music and want to hear more of it.

AD: I hear you have a lot of support from the community. What is your view of the orchestra’s role in the community?

MP: I’m a giant fan of business writer Jim Collins, whose Good to Great is a phenomenal book. He’s written a supplement for the non-profit social sector [Good to Great and the Social Sectors].

One of the concepts he discusses is the need to find what you can do better than anyone else in the world. To apply this to us, we have to decide what the Elgin Symphony Orchestra can do better than anyone else. I don’t believe it is Beethoven 9 – Berlin will do that better than us for a long time. What we can do better than anyone else in the world is to bring highly-educated people, wealthy people, and opinion setters into downtown Elgin. That needs to be key in all our decisions. A lot of orchestras take the phrase “serve the community” and interpret it as programming for segments of the community who do not attend their concerts. I’m not sure that’s how we can serve Elgin best. Elgin has a history of being blue collar; we had real gang problems in the past. The downtown is becoming great – if we bring people into downtown and show them what is happening, we can add great value to the city for everybody.

In some ways, this almost has turned us into a department of the city – we’re as important as the Parks Dept. or the Police Station. We have a very close relationship with the city government.

In the end, we think we are doing a lot of things right, but we also cannot forget for a moment that our success really is due to our location, the fact that there’s not a lot of competition in Elgin, a lot of upper income and educated people are moving in along highway 90, and that this is the age of the suburban orchestra.

An Interview with Sean Stegall, Assistant City Manager of Elgin

Sean R. Stegall is the Assistant City Manager and Budget Director for the City of Elgin IL. In his role as Budget Director, Sean is responsible for the preparation, execution and monitoring of a budget of $277,000,000. Sean also works directly with the Elgin City Council and the City Manager on all critical projects and issues related to the formulation of city policy, and serves on the board of several non-profit agencies. Sean came to Elgin from Batavia NY, where he was Assistant City Manager/Director of Administrative Services.

Ann Drinan: Tell me a little about Elgin and its recent growth.

Sean Stegall: It’s difficult to talk about Elgin because, unlike most cities, it is changing so rapidly and so many projects are going on at the same time – I don’t know where to begin. Elgin is a community undergoing rapid growth; we have several thousand new residences each year, with urban redevelopment occurring in the downtown. A city usually has one or the other, but we have both, at significant levels, at the same time.

Eglin is diverse; it’s 35% Hispanic, 8% Laotian, 7% African American, and the rest is Other. We’re going from a very middle-class community to a younger and more affluent community – this is happening to a lot of communities in the greater Chicago area. So we’re redefining ourselves: over the past five years, we’ve embraced the arts more globally, in addition to the symphony. We’re trying to make a major statement as a regional arts center and are positioning ourselves as a viable option to Chicago, where we serve as the secondary market.

SS: I come out of a budget, finance, and urban-planning background. When I came to Elgin almost 7 years ago, one of my assignments was to manage the Hemmens Performing Arts Center, which I didn’t know about when I accepted the job. Over the course of time, though, by being exposed to the symphony as our largest tenant, I know much more than when I started, which was nothing. I now know what an acoustician is and that it’s a science, not hocus pocus. I know the different components of the orchestra. Through the tutelage of the board, the executive director, and the entire organization, I’ve become a true believer.

SS: Elgin went through some difficult times in the late 1970s and mid-1980s, much like Cleveland and Pittsburgh – we were losing our manufacturing base, as we’re part of the rust belt. But we still had the Elgin Symphony, which had really grown and was performing at a high level. With all the difficult things going on, the residents were proud of the symphony. Because of that, as Elgin is changing –our reputation is well beyond what it used to be and there’s great excitement at the renaissance of downtown – more than ever there’s a close connection and bond with the symphony.

Now that the city has the resources, we want to do a lot for the symphony. It was the one thing we had to be proud of then; they were there when we needed them.

The experience economy [a phrase taken from a 1999 book by B. Joseph Pine II and James H. Gilmore with the same name] tells us that, if we build a beautiful concert hall, we will have many people who will come because they can appreciate the beauty of the facility and admire the artists creating the music. The actual music, for many, is a secondary consideration. I understand the importance of the symphony as an economic development tool, and I can admire the craft and artistry involved. If you build a beautiful building, it has an effect on people’s emotions and perception of Elgin. It’s much more than a concert hall. For example, I can enjoy watching a cellist do something amazing, and I can separate that perception from the music itself, which doesn’t move me as much as it does others.

The new hall will be the focal point of people’s perception of the revitalized downtown. You can build a hall that’s a 10 on an acoustic scale but if it doesn’t have the fine finishes, so that it’s part of a greater idea of a special experience in a great place, the music will not be enough to sustain it.

SS: We’re talking about a flexible space. but that’s the great debate. Will it be a pure concert hall or something more versatile? The technology continues to change. At this point, the decision will come down to our overall goal. If the main driving force is to see the symphony maximize its potential, well, a pure concert hall is held in higher regard than the best possible performing arts center. We went to Dallas and visited Bass Performance Hall, which is a multi-purpose hall, and Myerson Symphony Center, which is a pure concert hall. We heard performances Friday in Bass and Saturday in Myerson, and you really could tell the difference.

Seven years ago, the Hemmens Center seemed great, but now it seems inadequate. The symphony’s growth and its ability to generate more and more interest makes us realize that it’s time to move on and grow with them.

AD: What type of financial support do you give to the symphony?

SS: Our annual support has gone up – we helped to underwrite their recent recording and the new Friday matinee concerts they’re adding.

The riverboat casino has helped immensely. We were struggling economically, so we applied for the license. Now we’re realizing $25 to $30 million a year from the riverboat. So over three years, we’ve had $300 million to fix up the streets and old buildings, support arts groups, build a new golf course, rehab parks, tear down vacant and dilapidated houses in older neighborhoods,and fix up historic homes. You can do all that in 10 years if you have that kind of money earmarked for revitalization.

AD: How would you describe the relationship of the symphony with the city?

SS: Our relationship with the symphony’s management is a close one, because of the role that the symphony plays in the city. Typically, what’s in the symphony’s best interest is also in the city’s best interest and vice versa. And it doesn’t hurt that we have the financial resources to help meet their needs.