Dayton Philharmonic

Orchestra Spotlight: The Dayton Philharmonic

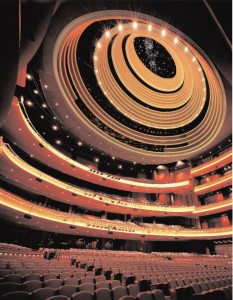

The Dayton Philharmonic celebrated their 75th anniversary in 2008 and released an anniversary CD (featured here on our Spotlight), but their big celebration was in 2003, when they moved into the new Benjamin and Marian Schuster Performing Arts Center that March and started performing in the breath-taking Mead Theater. In honor of the occasion, they published a commemorative book full of historical photos and the history of the orchestra. I attended the ROPA conference in Dayton in August 2009, and the delegates were given a tour of the arts center. Spectacular, gorgeous, and envy were the predominant comments / emotions.

Built in a block that formerly housed an empty department store, the Schuster Center was designed by architect Cesar Pelli & Associates of New Haven CT with a very futuristic motif. It includes a 2300 seat Mead Theater, a smaller theater, a restaurant opening into the Wintergarden complete with palm trees set against a block-long, glass-enclosed atrium, and a tower with offices and condominiums above.

The interior was designed to celebrate the role the Wright Brothers played in Dayton’s history. The very top of the hall’s dome has a fiber-optic replica of the galaxy, known as the Starfield, as it appeared to Orville and Wilbur Wright the night before their first flight, December 16, 1903. The width of the Starfield is the exact width of the Wright Flyer’s wingspan, and the length from the Starfield to the back wall of the hall is the distance of the Wright Brothers’ first flight. The hall has hundreds of fiber-optic lit crystal knobs lining the entryways and corridors that carry the star theme throughout the hall, for a spectacular yet warm effect.

The DPO was founded in 1933 by Paul Katz, a Dayton violin prodigy who would lead the orchestra for several decades. On their tenth anniversary, they moved from the Victoria Theater into Memorial Hall, and throughout the 40s and 50s the DPO grew in number of musicians and concerts offered. By the late 1950s the DPO was presenting 12 Young People’s concerts, causing traffic jams downtown because of all the school buses. Much of the DPO’s growth was owed to the generosity of Miriam Rosenthal, who died in 1965; the Miriam Rosenthal Trust Fund continues to support many of the DPO’s activities, including its 75th anniversary CD recording. The Dayton Philharmonic made its first recording in 1967 as a fund-raiser for the National Audubon Society.

After 42 years of service, Paul Katz stepped down from the podium in 1975 and, after a search, the baton passed to Charles Wendelken-Wilson (aka Maestro Two-Ws), assistant conductor of the Boston Symphony under Erich Leinsdorf and principal conductor of the New York City Opera. In 1983 the DPO released a commemorative album celebrating their 50th anniversary, Enriching your life with music, and the League reclassified the DPO as a “regional” orchestra (up from “community” orchestra).

In 1987 Isaiah Jackson, former associate conductor of the Rochester Philharmonic, was named the third music director of the DPO. In 1988 the Dayton Concert Band came under the auspices of the DPO and was renamed the Dayton Philharmonic Concert Band — they continued to give concerts until just recently. This year also marked the 50th anniversary of the Dayton Philharmonic Youth Orchestra, celebrated with a performance at Carnegie Hall.

During his seven years as music director, Maestro Jackson forged alliances with the African-American community in Dayton with a new series called “Focus on Our Heritage” featuring Andre Watts, among others. Curtis Long joined the DPO as Executive Director in 1994 and served in that capacity (renamed President) until 2008, when he was succeeded by current President Paul Helfrich.

A music director search resulting in five finalists from 200 applicants culminated in Neal Gittleman accepting the position in 1995: “My mission as the DPO’s next music director is to take a very good orchestra and make it a great orchestra.”

The DPO launched SPARK (School Partners with Artists Reaching Kids) in 1997 — a unique program that provides intensive musician interaction with the same classes of children over six years. Gloria Pugh, Director of Education, will be presenting more details in a forthcoming Polyphonic article. The DPO offers more educational programs than any other orchestra in the country — over 1,000 educational performances a year!

The DPO recorded its first CD in 1999 with the premiere recording of Tomas Svoboda’s two piano concertos, with the composer and Norman Krieger at the piano; the CD was released in 2001. Also in 1999, in honor of the Dayton Peace Accords, the DPO welcomed the Sarajevo Philharmonic for an historic Concert for Peace as they began a two-week USA tour.

In 2004 they recorded a CD of flight-related pieces by William Bolcom, Steven Winteregg, Michael Schelle, and Robert Xavier Rodriguez, honoring the Wright brothers’ first flight.

The current economy has been difficult for Dayton, as for so many other orchestras, but their 2010 negotiations are concluding with mutual cordiality and an understanding of what must be done to continue the excellence of the orchestra in demanding times.

This spotlight features 7 voices from the DPO:

On Page 2, Neil Gittleman, Music Director, gives his overview of the DPO as he enters his 15th year with the orchestra, lauds the musicians as their greatest asset, and describes the various concert series offered by the DPO.

On page 3, Chad Arnow, Bass Trombone and member of the Players’ Committee, talks about the current issues facing the musicians of the DPO, and the relationship of the musicians with management and music director. He also tries to explain the amazingly complicated world of DPO musician contracts — 9 contracts specifying specific seats in the string section and various principals and assistant principals — each with a different guarantee!

On Page 4, Paul Helfrich, President, gives a history of Dayton and its current economic situation (late 2009), describes the governance structure of the orchestra, and explains how it was possible for a regional orchestra like Dayton to build such a beautiful hall and make recordings (another coming out in 2011).

On Page 5, John Kurokawa, Principal Clarinet and Chair of the Players’ Committee, gives his insights on intra-orchestral politics, discusses those blue denim shirts, and concurs with Neal Gittleman that the musicians are what make the DPO unique.

On Page 6, Wendy Bohnett Campbell, President of the Board, talks about Dayton, why she loves living there, and its economic structure. She is quite proud of the Stained Glass series she helped start, in collaboration with area African-American churches.

On Page 7, Gloria Pugh, Director of Eduation, describes in detail the remarkable education programs presented by the DPO — they present more educational concerts than any other orchestra in the USA! In particular the SPARK program should be of interest to every orchestra — Gloria and I are working on a detailed article for Polyphonic explaining in depth how SPARK works.

On Page 8, Colleen Braid, Assistant Principal Viola and a SPARK musician, describes how she puts together the programs she presents to the children.

Ann Drinan, Senior Editor, March 2010

Interview with Neal Gittleman, DPO Music Director

Neal Gittleman became Music Director of the Dayton Philharmonic in 1995. He introduced the Classical Connections series to Dayton, and has won the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) award for Adventurous Programming of Contemporary Music seven times since coming to Dayton. Prior to his appointment with the DPO, Maestro Gittleman was Resident Conductor with the Milwaukee Symphony.

Ann Drinan: Tell me what’s unique about the Dayton Philharmonic.

Neal Gittleman: The musicians – there’s a spirit here that’s really very special. So many guests who come toDayton – soloists and guest conductors – all say the same thing: the musicians have a unique attitude – they like to work. It’s a no‑nonsense approach to music-making; they come to rehearsal ready to play and work. “We’re just here for a short period of time, so let’s focus.” There’s not a lot of attitude or fooling around. Some orchestras seem resistant to nitty-gritty work. But not ours. When I guest conduct in other places, I sometimes encounter orchestras whose character is less open. There seems to be a shell. They put on their armor and only then are ready when they come to work – the DPO musicians don’t seem to need the shell to make music. A lot of touring artists assume that there’s an inverse proportion between nice and quality, and are shocked to find a good orchestra that’s also very nice.

The DPO has a tradition of being a commuting orchestra. When I arrived in town, one-quarter of the musicians lived inDayton. But now it’s shifted and many more people live here, and some of those who live inCincinnatihave moved to the northern suburbs to be closer.

AD: What does your season look like?

NG: We have 9 pairs of classical concerts, 6 pairs of Pops concerts, 4 singles of Classical Connections, 4 Families, 3 sets of Young People’s, and LOTS of educational programs. These really interested me when I came here as a candidate because I believe education to be important. In some larger orchestras, there’s a conflict because they want to minimize the number of educational services in order to maximize the number of services available elsewhere. InDayton, we have the same tension between educational services and services that have more revenue-generating potential. But we recognize the intrinsic value of education concerts.

And I think we’re getting even better at connecting to the community. Community service seems to be part of the DNA of the orchestra. This was true even before I came here. It’s a nice match up of the way I think a Music Director should be, and how the community thinks an orchestra should be.

AD: Describe the Classical Connections concerts.

NG: I started doing them inMilwaukee when I was Resident Conductor there. At the MSO a separate series with 3 or 4 concerts focusing on particular pieces or composers. When I came toDayton we created a new series out of what we were already doing. With our Classical concerts, in odd-numbered months, we did doubles, and in even-numbered months we did singles. So Connections now makes those even-numbered months’ concerts into doubles. Now all of our Classical programs are doubles, and with Connections we now do triples four times a year.

The Connections concerts are similar to the old Bernstein Young People’s concerts but they’re aimed at an adult audience. I use the Lenny’s approach of taking the music apart and showing what’s going on. But I get more into how the music works, rather than telling stories about what the composer was eating at the time. My intent is to plant some little land mines in the consciousness of the audience that will go off when we get to that point in the music. This gets the audience to become more active as listeners and more connected to the music we’re playing. They’re not as passive in the way they listen.

AD: Can you give me an example of how you constructed a Connections concert?

NG: Sure. The opening concert this season was Tchaikovsky’s 2nd symphony. So we opened the Connections concerts with the Sleeping Beauty waltz – a short curtain-raiser. We did demonstrations of the Ukrainian folk songs in the symphony and how Tchaikovsky used them, often by repeating the folk tune in changing contexts. To close the first half we played Glinka’s Kamarinskaya – a repeating tune over and over with different accompaniments – which is where Tchaikovsky got that technique. Then after intermission we did a complete performance of the symphony followed by a discussion session.

AD: Who comes to the Connections concerts?

NG: Some only come to the Connections, and some die-hards will come to both the Connections and the “real” concerts linked to them. Some look to it as an introduction to classical music – they need just a little more information than the die-hard music geeks.

We sell subscriptions to the Connections concerts. But we also offer a Friday night subscription of six concerts which is a mix of some regular and some Connections. The tone of the concerts is more relaxed than the regular Classical series programs. We used to wear blue denim shirts (with the sponsor’s logo) for the Connections concerts. But now we’ve switched to all-black, which everyone seems to like better.

The Connections concerts are easy to do because they’re fun to do. The question I always ask myself is, “What is it about this piece that really gets to me? What really excites me? How can I try to communicate that to someone else?” But it’s also a lot of extra work for me, and for our librarian, Bill Slusser. Bill prepares separate books just for the demonstrations, which is a lot of work, but it makes it much easier for everyone in the end.

AD: What kind of education programs do you present?

NG: When I arrived here some of our education programs were very much like what we do now – three Young People’s, a week of Magic Carpet concerts for little kids in community centers, and sending several ensembles into the schools.

Some of the changes we instituted include, the SPARK program, which was a major addition. We also added a high school concert, which became the 4th Young People’s concert. But the biggest changes have been content-wise – we’re working hard to make everything we do curriculum related in some way. This is most practical because of all the NCLB and state curriculum requirements. If teachers can’t easily see the hook to hang something that relates to a state mandate, they’re not inclined to do it. We try to make it clear to teachers how the concerts relate to the state requirements.

AD: Tell me about the SPARK program.

Neal Gittleman: The SPARK program has infected the other education programs we do. In the classroom it’s one musician, one teacher, and the students. Say the kids need to work on math and fractions, so one of our clarinetists developed a lesson that involves measuring the clarinet and the different sizes of its pieces.

At the beginning of the year we have a session with the musicians and teachers together to work out what they’re going to do. The schools release the teachers for a half-day to come. The first meeting is early in the fall, and they have another planning meeting later on. Musicians do six classroom visits, usually after the first of January. We’ve learned what’s important to teachers – we’ve make the presentations more relevant to what they’re doing in the classroom. Fundamentally it’s the musicians playing in the classroom, but we try to wrap it around a concept that’s important to the teacher’s goals. The kids have six visits from musician and a visit from me or Patrick Reynolds, our Assistant Conductor. SPARK develops a connection between the kids and “their” musician; it’s a really nice connection, especially for the younger kids. Towards the end of the sequence, we do a series of concerts for each grade level, K – 5. Now we have a whole flock of kids who’ve come through their primary school career and have been connected to the orchestra every year, getting to know a different musician each year. Music and the orchestra have been a part of their lives all through elementary school. This will change the way they think about orchestras when they grow up.

AD: How do you pick the schools involved in the program?

NG: It’s very competitive. The process was developed by Artsvision, run by Mitchell Korn, who’s now Education Director in Nashville and, I believe, still runs Artsvision as a side business. He’s done a lot of programs with larger orchestras – San Francisco, Baltimore, Milwaukee… SPARK was the first time he did something similar with a smaller-sized orchestra. Now it runs on its own without Mitchell’s oversight.

SPARK serves a mix of schools – public, private, parochial, inner-city, and suburban. The most revealing thing is how different the kids can be within a given school and how it’s the teacher that makes the difference. I might be in an inner-city 2nd grade class and it’s what you might expect from the stereotype – the kids can’t focus, etc. But then I’ll go right next door and it’s a totally different. Same school. Same cohort of kids. But a different teacher changes everything. Being a good teacher in the classroom means that you know what you’re planning on doing but you must pay attention to the kids and adapt. Sometimes have to throw out your plan. It’s not all that different from what a conductor does in rehearsal. I don’t always rehearse just the list I prepare ahead.

AD: What are some recent highlights of your performances?

NG: We did Mahler 9 last February [2009] – it was really something. Really good. We surveyed the audience and so many people in the audience and our trustees had the same response – they realized what an achievement it was to play the piece. TheDayton musicians had mastered it; it was like climbingMount Everest – they hadn’t just survived but they actually summitted!

We played Beethoven’s 5th to end this past season – it’s an interesting experience because I had a revelation while studying the piece. I was going through the same issues, as I’ve done it many times. This time, however, I decided to do it the old-fashioned way – not being just hell-bent on keeping the tempo up. We played it the way we remember from the old recordings of Ormandy – more romantic. It was really fun. I had to get rid of that notion that “this” is the right way to do it and everything else is wrong!

AD: What do you see as the future of the Dayton Philharmonic?

NG: The biggest thing is, can we keep doing what we’re going with the economy as messed up as it is. A lot of it is psychological – some wealthy patrons are scared to write the same check they were writing in the good years. We need to figure out how to get through the next few years.

I tend to be a very optimistic, if worried, person – if we keep one nostril above water we’ll be able to come through on the other side. But we’re performing without a net now. It’s a scary proposition. We figure out ways to make the impossible possible – but these are scary times. We’re an important part of the community with all our education programming . Foundations like to fund education activities, but they’re giving out less money. And education concerts don’t bring in significant ticket revenue. Tough decisions have to be made – what are our core operations? What things do we really have to protect at any price? What sacrifices do we make to keep the core things safe?

Interview with Chad Arnow, Bass Trombone and Committee Member

Chad Arnow is the Trombone and Tuba Instructor at Xavier University and the Low Brass Instructor at the College of Mt. St. Joseph. He holds MM and BM degrees from the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music (CCM), where he is currently working on a DMA.

Ann Drinan: How would you describe your relationship with your management?

Chad Arnow: Generally it’s a positive relationship. Obviously we’re always working from opposite sides of the table – they want more work for less money and we want more money for less work – but it’s a respectful relationship even if we don’t agree. We’re all in agreement that we can’t make it so difficult that the other side can’t do their job.

We’re finishing up the last bits of negotiating right now– it looks like there will be cuts. I don’t know if this is round 1 of cuts or if there will be more in the future. I don’t want to comment more because we’re still negotiating – we still have a few points to agree on, and then the memorandum of agreement must be prepared and voted on.

AD: The economy in Dayton must be difficult right now – not optimal for contract renewal discussions.

CA: We’ve lost a lot of manufacturing jobs. Several automotive plans have closed (Ford and GM), and Delphi automotive parts had a couple of plants shuttered or operating way below capacity. NCR and other big corporations have left town as well. The economy is bad everywhere, but because we’re a manufacturing town we are hit a little harder in this kind of economy. Finding a donor base and keeping them engaged can be a problem in good times – it’s so much more challenging in this economy.

AD: Do you have musicians on the board? How does the DPO governance structure work?

CA: We have no musicians on the board, although a few former musicians (including our retired tuba player) are now members, but that’s coincidental. We are invited to board functions as observers. When we did our search for a new President two years ago, we had two musicians on the committee (John Kurokawa and myself). We have representatives on all board committees, though they are non-voting. We’re not official members but we are a part of things.

AD: How is your new president working out?

CA: The management and board have been much more communicative than we’ve seen in the past. Paul [Helfrich] does a really good job of communicating frankly, where we didn’t feel we had such a direct, open line of communication in previous administrations. When we have interactions with Wendy [Campbell, Board President], she is very forthright. She has a very strong business sense – she was interim President when we were searching for a new President – and she makes people live up to their projection numbers. She holds departments accountable. She may not be familiar with the whole collective bargaining experience for musicians but she’s very open and honest, even when the information is not pleasant. She’s been sitting in on the negotiations – this is the first time a member of the board has been so involved in negotiations in my memory.

AD: Are there disagreements or tensions among the musicians?

CA: It’s always a challenge to balance the different levels of work guaranteed to different musicians – some are guaranteed only 70 services while others are guaranteed upwards of 150. Principals and front of section strings who do the 40 ensembles services are guaranteed around 200 services right now.

So some musicians earn what passes for a living wage, while for others it’s very much a part-time job. Scheduling is always an issue; some prefer daytime services, but this is difficult for the people playing only 70 services. Our per-service rate is around $120 – it’s grown a lot over the years. My guarantee was 64 services 10 years ago when I joined the orchestra, and it’s now at 129; I was actually offered 101 services that first year and 134 this season. We’ve expanded our season quite a bit, though it’s contracting over the next season a little bit because of the economy.

AD: What do the musicians think of the SPARK program?

Chad Arnow: SPARK – it’s a curious thing because there’s nothing in our contract that specifies how many musicians will be involved in SPARK each year. That is sort of outside the CBA, so they could change the number of musicians without negotiating the change. But it’s a well-funded program, so it’s not affected as of yet.

The SPARK musicians (including our conductors) do lesson planning, and go by themselves into the classroom to work with the kids and their teachers. It’s really outside what we all learned in music school. Sometimes the meetings are earlier in the AM than our SPARK musicians might prefer, but if that’s the biggest complaint they have about the program, they’re not doing too badly!

AD: How many different contract levels do you have?

CA: Nine – A through I. Each contract has a different number of services guaranteed for specific positions. For example, the A contract guarantees 150 service to most principals. However, the level B contract guarantees 147 services to the principal trombone, and the level C contract guarantees 144 services to the principal percussion. My guarantee, level E, is 129 services for 2nd and bass trombones, first violin chairs 7 & 8, and second violin chair 6.

AD: I’ve never heard of such specific guarantees for individual chairs!

CA: Yes, it’s all by position. Most people have historically been offered more than their minimums, but nothing is guaranteed beyond what’s stated in their contract.

Some people make around $30,000, which combined with teaching can be close to a living wage in Dayton. Some of us are school teachers, and some are part-time or full-time college professors, teaching at the University of Dayton (a Catholic school), Wright State University, Central State University (a historically African-American college), Cedarville University, a Christian school, Xavier University, and the University of Cincinnati among others. Others have “real jobs” that include things like piano tuning; one of our cellists is an anesthesiologist.

AD: Do most of your musicians live in Dayton?

CA: About 40% of us live within 20 miles of downtown Dayton. Cincinnati is only about an hour away – Columbus also.

AD: What do the musicians think of Neal Gittleman?

CA: We get along generally very well – over the last few years, more and more it feels like he’s on our side in an increasing number of ways. He obviously must work the rehearsal schedule to minimize or maximize who’s on a given service, so the low brass may not be needed for certain rehearsals for example, but that’s to save money for the organization. He’s respectful of the musicians, and we of him. Our relationship is good, and he’s certainly not difficult to follow, he knows his scores, and the community loves him. He’s pretty hard to hate – we could do much, much worse!

Interview with Paul Helfrich, President

The 2009-2010 season marks Paul Helfrich’s second season as President of the DPO, succeeding Curt Long. Prior to coming to Dayton, Paul served for 12 years as Executive Director of the West Virginia Symphony Orchestra. He has also held positions as Executive Director of the Erie Philharmonic and Marketing Director of the Kalamazoo Symphony Orchestra. He is a proud graduate of the Indiana University School of Music.

Ann Drinan: Tell me a little about Dayton.

Paul Helfrich: Dayton is like a number of other cities in the Midwest – in transition from an industrial economy to the economy of the future, whatever that may be. Old heavy manufacturing will never return. If you were to go back about 30 years, you could characterize people by where they worked – the Cash [NCR – National Cash Register], the Fridge (which was the Frigidaire refrigerator plant), the GM plant – they were big employers with all sorts of ancillary businesses. They have scaled back operations and just this past June, we finally lost NCR for good. They’ve maintained their headquarters here but now they’re moving to Atlanta. They’ve been here for 125 years, founded by John Patterson. Several streets are named after him, as is Wright Patterson Air Force Base.

The Wright brothers are another source of city pride, part of our history of innovation and invention. Dayton also had Charles Kettering (there’s a suburb named after him) – the founder of Delco (Dayton Electronics Company); he invented the electronic starter for automobiles. There’s still a lot of technology and innovation in Dayton, but now it centers around Wright Patterson Air Force Base, which is a facility that’s benefited from the BRAC process (military base closures) because of its budgetary efficiency. As other bases are scheduled to be closed and still others are consolidated, Wright Patterson has expanded. Quite a number of small high-tech firms have grown up around the base.

AD: In your opinion, what is the current state of the orchestra?

PH: The challenge for the orchestra is that our philanthropic connections have typically been to the industries of the past – to their executives, lawyers, accountants, etc. As they’ve left Dayton and the banks have consolidated, we’ve lost those connections in terms of individual and corporate philanthropy. We need to cultivate relationships with the technology companies that are involved with the Air Force base and the defense industry. But we don’t have that history, so we have a lot of catching up to do.

There are many models of communities that have made the same transition that Dayton is facing, such as Pittsburgh with its steel industry and mills all gone. Dayton is now a regional center for education and health care. We call it “Eds, Meds, and Feds.” We must look to the University of Dayton, Wright State University, and Miami Valley Hospital and other health care centers for our new audience base, even though the orchestra and most of its colleagues in the performing arts don’t yet have the right the connections with Eds, Meds, and Defense.

We have urgent and important needs – the long-term viability of the region is dependent upon our being able to attract new jobs. The arts serve as a drawing card; we have a really good symphony and a modern, new, state-of-the-art concert venue. Certainly this is a factor in attracting physicians to Dayton’s hospitals, and engineers to the new technology firms.

AD: The economy must be really hurting the symphony’s bottom line right now.

PH: Ohio’s economy tends to get hit first in a recession and recover more slowly – statistics show that Ohio’s state-wide unemployment is above the national average. But the other big factor to consider is what happened to the stock market this past year. During the recessions of the early 90s and post 9/11, there was a sense that we were going through hard times but I always sensed that for people who had wealth, it didn’t affect them in nearly the same way that it did working people. Now we have people with a history of major support suddenly worried about whether they’re going to be OK or whether they’ll outlive their money. People on the cusp of retiring are reconsidering their contributions to the DPO. People do cherish the symphony, along with the Art Institute, ballet, and opera, but the state of their personal means has definitely been challenged.

AD: Tell me a bit about your education programs.

PH: We have cultivated the relationship of the orchestra with the school systems and have sought to make education a key part of our mission rather than an ancillary part of it. Many orchestras are coming around to this. When I was in West Virginia, they were moving in this direction and had embraced a Dayton-like model, but Dayton was a real leader in establishing that critical connection with the school systems.

I give a lot of credit to Neal [Gittleman}, to Curt Long my predecessor, and to Gloria {Pugh] because she has such longevity here. The musicians of the orchestra have really bought into SPARK – we’ve never had a SPARK musician quit the program (other than by moving away from Dayton). The participating musicians really enjoy the program and find it meaningful.

AD: Your new hall at the Schuster Center is really beautiful. How was Dayton able to afford to build such a wonderful facility?

PH: There are lots of analogies between Charleston and Dayton. The West Virginia Symphony played in a big barn (Municipal Auditorium) with 3400 seats. Memorial Hall here in Dayton was very large, and not designed for symphonies. Both West Virginia and Dayton moved into new halls in 2003. The buildings had different architects but the same acoustician: JaffeHolden. The Mead Theatre in the Schuster Center has 500 more seats than the Clay Center in Charleston, but both cities went through a similar process of determining that new facilities were needed, marshalling support in the community, and finding the resources.

The orchestra played a key role in both communities as well. Neal’s arrival in Dayton was key to that here, in that the orchestra, under his leadership, began to achieve ever higher levels of artistic excellence. And Neal is a great advocate for the orchestra – his example and presence in the community had a lot to do with the new hall becoming a reality.

AD: Do you have to share the hall with other arts organization and touring shows?

PH: The hall is used for most DPO performances, Dayton Opera does three staged productions, and Dayton Ballet does the Nutcracker there. Most touring Broadway productions use the Schuster Center as well, although there is also an old theater from Vaudeville days across the street, Victoria Theater, that seats about 1000.

There is an enlightened scheduling process in place; we’re working two years ahead of time so that the DPO is able to secure a schedule that makes sense for us. The hall doesn’t bring in big shows in a way that hurts the orchestra. When funds were being raised for the building, it was touted as the new home of the DPO, opera, ballet, and theater association, and it’s run in such a way that benefits all those constituent organizations.

AD: Dayton was recently named one of the 10 fastest-dying cities by Forbes magazine. You had a symposium with the other cities in that article. What was the outcome?

PH: We exchanged success stories about economic development, and restoring and maintaining the vitality of downtown. And we talked about the vital role that the arts can play in maintaining their communities. Dayton is changing – it’s different than it used to be. Negativity is everywhere. But even though its population is declining, it’s still a very vital community. We are going to keep our heads up and fight our way through this. It may be a bumpy road, but we’ll get through it.

AD: What’s the governance structure of the DPO?

PH: I’ve been in Dayton since the late fall of 2008. Before coming to Dayton, I negotiated four agreements with the West Virginia Symphony. We have a good but a traditional relationship with the musicians. The primary interaction of the board and management with the orchestra here is through the Players’ Committee. A few committees of the board have musician representation, but not all of them. The Artistic Advisory Committee looks at the surveys from the musicians after every concert. Many conductors wouldn’t deign to for such a process to even happen, never mind pay attention to the results. But Neal’s view is, “I’ve been here for 14 years. If I don’t make a conscious effort to keep things fresh, then they won’t be fresh.” So he really listens to feedback from the players. This type of collegiality means a lot to the orchestra.

We do have an issue in that a significant number of players don’t live in Dayton. Many live 45 minutes to an hour away, and that’s been a factor in our scheduling.

The board is in transition, much like the community. We have fewer CEOs and executives on the board than in years past because the number of companies in Dayton has diminished, and those that remain don’t have the same sense of community involvement.

When a city mounts a major effort to build a new facility, that can pull some of the board talent in that direction. The marketplace for board membership in Dayton does seem to have become more competitive in recent years. The board had 32 members when I arrived and the bylaws would allow for 10 more than that. The board has become a bit complacent about getting its numbers up. I agree with Henry Fogel – that orchestra boards should be big, which can make governance messy, but that is more than balanced by the gain in advocacy, community engagement and fundraising.

AD: Tell me about your current recording project. How is an orchestra your size able to afford to record?

PH: We premiered and recorded Lowell Liebermann’s Clarinet Concerto in early November 2009 with Jon Manasse, and we’ll perform and record his Trumpet Concerto in January 2011 with Ryan Anthony. The recording will be made by E1 Music (formerly Koch Classics) and released in 2011.

The funding for the Liebermann project comes from a private patron of Mr. Liebermann’s. Other CD recordings we’re planning will be funded by a generous foundation in Dayton – the Miriam Rosenthal Memorial Trust Fund, which has been supportive of many of our past special projects. The first phase of the Rosenthal “New Media Initiative” has allowed us to stream our concert broadcasts on the internet.

One of our challenges, now that we’ve moved into the Schuster Center and found a new home at a level befitting the quality of the orchestra, is to determine what is next for us in this industrial Midwest city in transition. Carnegie Hall? A European tour? We’re going to have to find things that make sense for this community. I like to say that “quality may be universal, but relevance is local.” The goals of The Cleveland Orchestra may not be the right goals for the Dayton Philharmonic; we need to find our own way.

Interview with John Kurokawa, Principal Clarinet and Chair of the Players’ Committee,

John Kurokawa joined the DPO as Principal Clarinet in 1996, after completing an MM degree from the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music (CCM) and a BM degree from Bowling Green State University.

Ann Drinan: How would you describe your relations with management?

John Kurokawa: Paul [Helfrich] has been very transparent, open and honest, and very communicative. He’s really quick on the draw when it comes to communications; he moves things along very quickly, which is great for us. We got started negotiating a lot earlier this time than we usually do. The negotiations are difficult but very professional on both sides, in the face of what’s been happening with the economy and the state of the orchestra. I’d describe relations as very congenial.

AD: What about your relation with the music director?

JK: In my opinion, the DPO is vey lucky to have Neal [Gittleman]. Musicians always have complaints about their conductor, but not too many orchestras have a music director who lives in the community and works tirelessly to raise money. He’s great at fundraising, and he’s donated large sums of money to the orchestra. Neal is a real presence in the community.

AD: What do the musicians think of the Classical Connections concerts?

JK: The appeal of the Connections series is that it’s like Music for Dummies – I often encounter musicians who say, “I didn’t know that!” I find them interesting, and family members and patrons I’ve talked to really appreciate them. They draw in a different crowd because it’s a different concert format; they appeal to people of all levels of interest. Musicians too. For example, with a Beethoven symphony, Neal will take a specific section’s theme, and take the audience through the first 2-3 drafts of that theme. And the musicians like them because we don’t have to wear tails.

AD: Do the players like wearing those blue denim shirts I saw on the DPO website?

JK: We don’t wear those anymore. The Dayton Daily News used to sponsor this series, and they provided the blue shirts. Now we have a different sponsor, so we wear pit black. We also like these concerts because they’re sandwiched in the middle of the subscription concerts – it’s a nice little break for the musicians.

AD: How is the orchestra’s relationship with the local?

JK: We have a really good relationship with the local. The President, Kareem Powell, is very supportive of the players committee, and is very involved in the negotiation process. And Secretary/Treasurer Don Sutton is excellent at keeping track of our finances.

AD: You play in such a beautiful hall – must be nice!

JK: It is beautiful, and acoustically it’s one of the nicest spaces I’ve ever played in.

AD: What makes the DPO special?

JK: One of the things that makes DPO special is the humanity of the musicians – the supportiveness of the musicians to their colleagues. It’s just a very pleasant place to go to work. I’ve played in other orchestras where that’s not the case. I guess what makes us special is our lack of controversy – our ability to get along.

Interview with Wendy Bohnett Campbell, Board President

Ann Drinan: Tell me a bit about yourself and how you got interested in the DPO.

Wendy Campbell: One interesting fact is that my brother, David Bohnett, is Board Chair of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and my cousin, Jim Mabie, is Vice Chair of the Chicago Symphony. My family has always been big on community involvement – David loves LA and I really like Dayton, but we’re all from Chicago. We believe in making an investment in the community; it’s our ability to give back to the community that’s truly meaningful for us. Both David and I are very touched by music; it gets to my soul.

AD: Tell me about your involvement with the orchestra.

WC: I’ve only been the Board Chair for a few months [since June, 2009]. I was interim Executive Director between Curt Long and Paul Helfrich – that was the best training possible for becoming Board Chair. I’m good at running organizations, and that gave me the inside knowledge I needed to be an effective Board Chair. I’m not from corporate America or big money. In fact, I’m a new model for a symphony Board Chair – a single mother who’s made her own way.

When I was appointed Board Chair, I took every new board member out for a personal meeting over lunch or breakfast, so I could get to know their interests. New board members are often much more engaged; once I identified their interests and strengths, I could steer them to the right committees, so they could become more productive very quickly.

AD: Tell me about Dayton. What makes it unique?

WC: I’ve lived here since 1974 and really like it. Dayton has a low cost of living, no traffic jams, and it’s very accessible.

Dayton is the birthplace of aviation – the Wright brothers had a bicycle shop here, and Huffman Prairie was where their first flight took place. They later took their plane to Kitty Hawk because of the better winds there.

Wright Patterson Air Force Base is the major employer; I believe they have had as many as 30,000 employees. It’s probably closer to 10 – 20 thousand now. I was a manager in R&D at Wright Patterson. As a manager, I’ve built relationships where I’m seen as a member of the team. I’m much more approachable than many managers.

AD: How is Dayton faring during this recession.

WC: The big news is that NCR [National Cash Register] is moving to Georgia – they’ve been headquartered in Dayton since 1884!. The biggest employer is Wright Patterson Air Force base, and the DPO needs to target defense contractors, but their home offices just aren’t here. We have only satellite offices in Dayton. We lost a big GM truck plant recently. LexusNexus is here, but they’re outsourcing.

AD: How big is your board? What sort of governance structure do you have? Are the musicians involved with the board?

WC: We have 35 people on the board, and we invite members of the Players’ Committee to attend every board meeting, plus ask musicians to serve on many committees throughout the year. The president of our volunteer association, which is a separate 501(c)3 entity, is on the board. We’re increasing our governmental affairs presence; we’ve been advised to do so by people who are knowledgeable to get a better presence in Columbus. We need to be a bigger player in state politics.

AD: Tell me about your community engagement efforts.

WC: I helped start the Community Advisory Committee; we started a free Stained Glass series where we paired ourselves with three African-American churches. We give concerts at their church on a Sunday afternoon and pair it with a reduced ticket price to our regular concerts. We give them about 75 tickets for $5 and $10 each, which brings a lot of the church to one concert. It’s been a very successful long-lasting relationship with the churches, where we’ve established a real relationship. It’s important to make the community believe that we’re the community’s orchestra. Whether people attend our concerts or not, they do see the value of the orchestra to the overall community.

We have a really good model with these Sunday afternoon concerts. Neal often spotlights African-American composers with a mini-Connections program, and then the church hosts a reception. Within a month, we invite them to come to “our home,” thus encouraging the church to come together again. The music we play may not be all that familiar to them, so it’s easier for them to come with their friends who also aren’t as familiar. We recognize them from the stage, and their church choirs are involved in the last part of the concert. We block out the seats so they can all sit together, and we have a special reception at intermission.

AD: What sort of special events do you hold?

WC: The Dayton Philharmonic Volunteer Association gives us a lot of support in fundraising. We’ve held successful bi-annual designer show houses – in fact we just finished one. They are also tremendously helpful in support of our education programs.

Interview with Gloria Pugh

Ann Drinan: Tell me about your involvement with the Dayton Philharmonic. How did you come to be the Education Director?

Gloria Pugh: I’ve been with the DPO for 17 years. I used to teach elementary general music, taught piano lessons, and worked in the music business. I volunteered to be a Dayton Philharmonic Volunteer Association docent when we first came to Dayton. Docents go into the schools to prepare the kids for our Young People’s concerts. So I was first a volunteer docent, then the script writer for the docent presentations, then chair of the Education Committee of the volunteer association, and finally the DPO Director of Education.

AD: I’ve heard great things about your SPARK program. How does it work?

Gloria Pugh: SPARK stands for School Partners with Artists Reaching Kids – we send individual musicians into the schools. The strength of the SPARK program is that the musicians plan directly with their partner teachers. The primary goal of the program is to more directly link music to classroom curriculum.

SPARK is quite distinct in that one musician is assigned to a school and a grade level, and that musician presents a series of six lessons. It’s very intense for the musicians because they must develop six viable lesson plans. For some of them it means that they must step way outside their comfort zone, as they’re used to performing in a group. Here they partner with a teacher in the classroom, but they are the sole creators of the programs. The classroom teacher is somewhat of a teaching partner. Most regional orchestras’ education programs provide one lesson to several schools; here we provide six lessons to the same school – to the same students.

The programs are planned with the teachers in the school building, according to their needs. We have six musicians going into each school, each at a different grade level; we now have nine schools in the SPARK program. If a child stays in the same school for six years, s/he will know six DPO musicians really well, having seen each of them for six lessons in a year, and s/he will also have seen them in six orchestra concerts. S/he’ll also know Neal Gittleman and Patrick Reynolds [DPO Assistant Conductor] really well, because they also visit the classrooms.

For kindergarten – 3rd grade we have special SPARK concerts given in the community. For grades 4 & 5 we have Young People’s concerts at the Schuster Center. The SPARK orchestral concerts deal with music and family, music and tales, musical mysteries (i.e., problem solving), and musical moods. The February Young People’s concert always focuses on a particular culture.

AD: How do you decide which schools will participate?

GS: We started with three pilot schools, and chose them according to their demographics. We wanted schools with broad demographics and who expressed an interest in a cross-curriculum adventure. Originally we had one Dayton public school and two suburban schools in the SPARK program. When we wanted to add another Dayton public school, two others also requested to join us. So we developed a rigorous application process for adding the second Dayton school. A firm prerequisite is that the entire building has to buy into the program – everybody must be on board.

AD: How are the musicians compensated for SPARK?

GP: SPARK is not part of their guaranteed compensation. We pay them a set fee per classroom performance, but we also pay them for five services for their time in planning their programs, meeting with the teachers and me, and evaluating the success of their programs.

Several musicians were quite taken aback when we started SPARK, but they have since expressed to me how much this program has meant to them. When they come back to the workshops in fall, it’s the same group of teachers and everyone catches up with each other. Some musicians even ask to do more programs. I try to balance out the work among all the musicians who want to be involved.

AD: How do you decide who gets to participate in SPARK?

GP: Typically we only have openings when we add a grade level to a new school, or if someone moves or leaves the orchestra. This year we had a musician retire and added a school, so we had four openings but we ended up with more people being interested than I had space for.

AD: How many musicians participate? Are they part of a core?

GP: We currently have 24 musicians in SPARK. It’s all extra work for them. We don’t have a core in the DPO. Some SPARK musicians are retired school teachers, and many teach privately.

SPARK has informed all our traditional programs. The ensemble programs have changed because of their experiences in SPARK. Our Young People’s concerts are now much more geared to cross-curriculum themes.

AD: Tell me about your ensembles. Their performances are not part of SPARK, right?

GP: Correct. We have five ensembles – all together they gave 352 performances last season. It’s a separate side contract, where they’re guaranteed 40 services and are paid by the service. They give two performances within a 2.5 hour service, and often give four performances in a day [for two services]. The ensembles [one string quartet, one string quintet, a brass quintet, a woodwind quintet, and the DPO trio: trumpet, bass, and percussion] have different programs for different grade levels.

AD: And then you have full orchestra educational programs…

GP: Yes, the Magic Carpet concerts, which use about 40 musicians, are for pre-school and primary school children and are given at various sites around the city, such as in temples, churches, and local universities. Then three Young People’s concerts, with around 60 musicians, are each given twice at the Schuster Center, and there’s also a special concert for high school students. This year we’re presenting Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet with an actor.

AD: That’s a huge commitment on the part of the DPO to educational concerts and being a strong part of the music education lives of Dayton students.

GP: Well, we also have two youth orchestras: a Junior String Orchestra, conducted by Betsy Hofeldt, and the Dayton Philharmonic Youth Orchestra for grades 9 – 12, conducted by Patrick Reynolds. The Junior String Orchestra was originally a feeder string orchestra for the Youth Orchestra and was just grades 6-8. But students that weren’t making it into the DPYO still want to play, so it’s now for grades 6-12. We used to have a high school concert band performance every fall and always sold out two performances.

What is amazing about the DPO is that, in a community of this size, we have an education program as large as it is – both in its breadth with the ensembles and orchestra concerts, and its depth in the SPARK partnerships. It’s a real tribute to the boards over the years that have been willing to support such a wide variety of education programs.

AD: You mentioned at the beginning of our conversation that you were a volunteer docent before you joined the staff. What do the docents do for the orchestra?

GP: The docent program began as a way to preview the concerts for those students coming to Young People’s concerts. It is a program which is created and run by the Dayton Philharmonic Volunteer Association. They create a script for each of the concerts and send the docents out in teams of two to meet with students in every school coming to a concert. The previews are meant to give the kids information about the composers, the music, the themes, and also basic concert manners. Traditionally they’ve done the presentations with posters and props. However, last year they put it all into a PowerPoint presentation which had great visuals. The DPVA won a Gold Book award at the League conference in 2009!

The Young People’s audience is so well prepared because of the docents. We did a Rhythms of Africa concert with drummers from Cincinnati. They started doing exercises about polyrhythms and all the kids already knew the name; the presenter was flabbergasted!

We’ve also created a program called The Orchestra and You. It’s an interactive program for 2nd grade where the docents bring in Lucite mockups of orchestra instruments. We create mini orchestra in the schools, and show the students how to hold the instruments, play recorded examples, and then form an orchestra and play a full orchestra tape. It’s a great interactive introduction to what is an orchestra.

AD: I’m amazed at your creativity in using volunteers to complement your education programs! How much training do the docents have in order to do these presentation?

GP: The education committee from the DPO volunteer association writes the script. We all go on a mini retreat, where I give them input about curriculum, and then write the three scripts. We have about 30 active docents, and they go to every school. Docent training is in the fall. They have three sessions with Neal and Pat. We get everyone comfortable just talking about the music and the themes of the concerts. Then we create the script and record the music segments. And now we also create a PowerPoint presentation with graphics, animation, sound clips, and transitions.

Click here to view the DPVA’s award-winning PowerPoint presentation.

Interview with Colleen Braid, Assistant Principal Violist and SPARK Musician

Colleen Braid as been with the Dayton Philharmonic for 35 years, and plays in both the SPARK program and the DPO’s string quintet. She is married to Jim Braid, a violinist with the Cincinnati Symphony, pictured here with Colleen and their first grandchild.

Ann Drinan: Tell me about your personal involvement with the SPARK program.

Colleen Braid: I’ve been involved since the start of the program – 13 or 14 year ago. The first year we went out in pairs and we only went to kindergarten and 1st grades, but then they added more grades, so we started going out alone.

It’s always a bit of a challenge. This year I’m working with four kindergarten classes in two very different schools – a Dayton public school, which is an inner-city school, and a private school in the suburbs.

The inner-city school has very large classes and the students not as advanced – sometimes they’re just learning to write their letters, and learning how to sit and behave themselves, when I come in December. The private school kids are very bright; they get a lot of attention from their parents and have had learning experiences before entering school, while the other kids may have had no experience in a school situation. They’re noisier but equally enthusiastic. The private school classes are very attentive, quiet, and quick to pick up activities. The public school classes are twice as big, so it’s a challenge for their teachers as well.

I love working with this age level – many of the children are seeing instruments and hearing music that they’ve never experienced before. I really enjoy doing the SPARK programs – the kids are so much fun. I’ve taught inner-city school kids before (I taught part-time for 20 years in the public schools), and I’m happy to work with the real young ones. Sometimes there are discipline problems, but that can happen in any school.

AD: How do you structure your lessons? You go to each class six times, right?

CB: Yes, I prepare six lessons. Each lesson has a story connected with it. I use a different book that the teacher reads, and I interject little bits of music during the page turns or between sections.

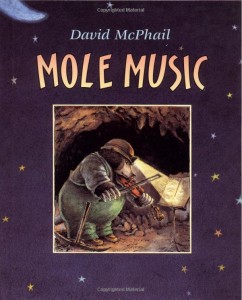

For example, the first lesson is about the book Mole Music – it’s about a little mole that lives underground, and who works digging big tunnels during the day. He sees a violinist on TV, wants to play one himself, orders it, it arrives, and he can’t do much with it. He learns one note at a time, sounding pretty awful and scratchy, and eventually he learns a couple of tunes. He plays his violin at night in the tunnels, thinking no one can hear him. Above ground, a tree is looking into the hole with dismay – as the mole gets better, the tree grows and blossoms. There are themes of music going through the tree, which indicate what I should play: Ode to Joy, themes from Beethoven’s Sixth, the last movement of Brahms’ First…

AD: What concepts do you present to the kindergartners?

CB: At the first session, I introduce them to the viola – how it works, what is bow hair, and vibrations – I let them pluck the strings of a cheap violin, and we play with rubber bands.

Last year I added a letter to each lesson – they use the letter to spell words for that lesson. The first is V for viola, violin, vibration; at the second lesson I introduce other families of orchestra – so it’s F for flute and fast; the brass family is T for trumpet, trombone, tuba, tempo, etc.

The climax of each lesson is when the teacher reads the story and I play. I used My Family Plays Music for the last lesson. It’s about a family that plays all kind of music; one of the children plays percussion, so I bring hand percussion instruments, like a triangle and maracas, and the kids take turns playing them as part of the story. They play along with me. I play blue-grass music, a little jazz piece…

The overall theme of the six lessons is about family – their family and the instrument families. My connection to their core curriculum is basically language arts, but I also work with patterns (math) and social studies (as in The Chinese Violin book).

AD: What are the six book you use for the six lessons?

CB: I use a different book for each lesson:

- Mole Music by David McPhail [described above]

- Barn Dance by Bill Martin Jr. and John Archambault, where a little boy hears a scarecrow playing the fiddle

- The Remarkable Farkle McBride by John Lithgow, about a young musical genius

- And To Think That We Thought That We’d Never Be Friends by Mary Ann Hoberman, where people move in next door and play music all night, annoying their neighbors. It ends up with everyone joining in and having a parade around the world, crossing the oceans on dolphins and sharks.

- The Chinese Violin by Madeleine Thien, about a little girl and her father who move to Vancouver, where it’s so different and hard for her. She learns to play the Chinese violin, which makes her special.

- My Family Plays Music by Judy Cox [described above]

AD: How is your relationship with the classroom teachers?

CB: I’ve been working with the same teachers for 5-6 years, which is a big help to me in the classroom. We have meetings at the beginning of the year where I go over the lesson plans with them. I try to change one or two things every year, such as different games that we play, or I’ll use a new book.

AD: Do the kids remember what you present to them from year to year? At the end of six years, they’ll have had 36 programs from 6 different musicians, plus at least orchestra concerts.

CB: We present a different program for each grade level, and they do remember from year to year. The feedback I get from other teachers is that, in the following years, they remember what we talked about – especially with reinforcement in the following years. These programs also make a great connection in the community.

AD: How are you compensated?

CB: I do four different classes – 2 kindergarten classes in each school. I get paid $75 for each in-school class, so $300 per lesson times six lessons. Plus we have five meetings, observations, and wrap-up sessions – we get paid a per-service rate for those, at principal scale.