A Visit to Spillville

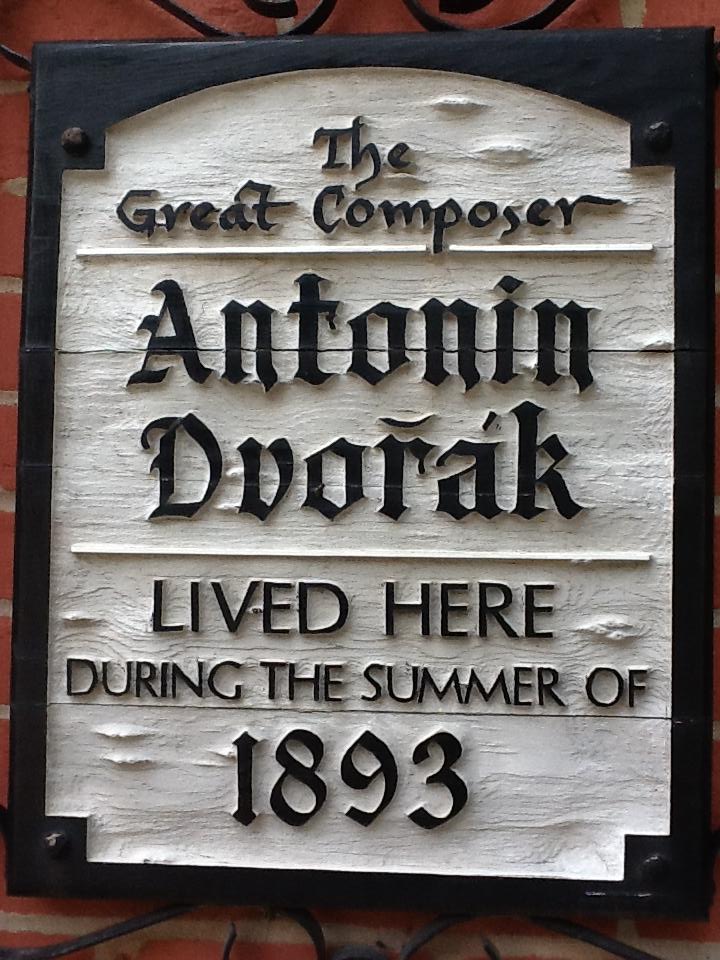

Dvorak and his family lived in this home, now the Bily Clocks museum, in Spillville, IA during the summer of 1893.

Spillville, Iowa is not exactly a popular tourist destination. Located in the northeastern part of the state in the midst of endless cornfields, it’s the quintessential rural midwestern town: a main street with small, family-owned stores, a couple of sleepy neighborhoods, and a few churches as old as the town itself. But that’s as typical as Spillville gets–for smack dab in the middle of this quiet Iowan retreat is a museum dedicated to the great Czech composer Antonin Dvorak.

For those unfamiliar with Dvorak’s Iowan connections, here’s a quick refresher: in the summer of 1893, after spending the past academic year teaching and composing at the National Conservatory of Music (Juilliard’s precursor), Dvorak desired a change of pace from the busyness of city life. But, unlike modern-day Juilliard professors, he did not have the luxury of escaping to the Aspen Music Festival, so he chose Spillville, with the hope that the city’s predominantly Czech population might cure his homesickness for Bohemia. The choice proved to be a wise one, as it turned out to be an extraordinarily productive summer for the composer: some of his best-known chamber music works, the “American” quartet and the viola quintet, were written in Spillville, in addition to a variety of other small-scale pieces. As a result, Spillville has become an almost sacred site for Dvorak enthusiasts, and even hosted a Dvorak Festival in 1993 to commemorate the one hundredth anniversary of the composer’s visit.

Last month, I had the opportunity to visit Spillville myself. My father, a professional cellist and the biggest Dvorak fan this side of the Mississippi, had planned a epic family road trip from Chicago to Wyoming, and figured that as long as we were heading west we might as well make a stop in the Dvorak Capital of America (I wasn’t entirely confident that this was really “on the way,” but I wanted to go, too, so raised no objections to the itinerary). Subsequently, around four ‘o clock on a muggy August afternoon, the Preucil family van pulled up on Spillville’s Main Street, just yards away from the house where Dvorak once lived. It’s a museum now; the lower floor is dedicated to a fascinating display of ornate clocks crafted by the Bily Brothers, who lived in Spillville some time after Dvorak, but the top floor is an extensive exhibit of relics and memorabilia from Dvorak’s time there. Stepping into the room where the master had composed was a little surreal; I could almost hear the scratching of his pen as he worked out the cello solo in the second movement of the American quartet, unfazed by the clip-clop of horse hooves echoing from the dusty street below. One especially interesting feature of this room was a display of the actual harmoniums Dvorak had used to compose and perform on that summer; they’re still in playable condition, although visitors are implored not to touch them.

After visiting the museum, we made the short drive over to the Turkey River, where Dvorak had routinely taken walks in the early hours of the morning. It is documented that he used to come up with melodies during these constitutionals and scribble them on his shirt cuffs, to the evident displeasure of the maids. A large rock monument sits along the riverside today, inscribed with the titles of some of Dvorak’s most famous works: “Rusalka”, “Humoresque”, the “American” quartet, and the “New World Symphony”, to name a few. Standing there in the uncut grass, swatting aside a unusually persistent swarm of mosquitoes and looking out at the water that sparkled in the late afternoon sunlight, it occurred to me that this place probably hadn’t changed all that much in the one hundred and twenty years that had elapsed since Dvorak had stood here, his imagination alight with ideas for some of the greatest works ever written. He had seen these trees, these waters, and had probably dealt with the ancestors of these mosquitoes. Putting myself in Dvorak’s undoubtedly muddy shoes, I felt as though I was able to glean a fresh understanding of the music that owed this place its existence. The vast expanse of prairie around me was the majestic opening viola solo of the American quartet; the exuberant trills of the birds above was the repetitious first violin part in its third movement; and the droning insects in the grass below had surely inspired the murky ostinato given to the inner voices in the melancholy slow movement. I was halfway across the country from the Sibley Music Library in Rochester, yet I was having an educational experience unlike any I could obtain from reading a history book there. I was experiencing the very forces of nature that had inspired music, and that brought me closer to Dvorak’s mind than any scholarly dissertation ever could.

The destination for that evening was Mitchell, South Dakota, which was at least another six hours away, so Dad (somewhat reluctantly) announced it was time to go. But as we drove out of town, we were treated to an unexpected musical surprise: the “American” quartet was being broadcast on our favorite satellite radio station. We chuckled at the coincidence–what were the odds?–but soon settled back and enjoyed the masterpiece, while Spillville faded into the distance and never-ending fields of dusk-colored corn soared past the windows. Sitting there in the backseat, wedged somewhat uncomfortably between the ice chest and my brother’s suitcase, I realized that the experiences I’d just had caused me to perceive the music I was hearing on a whole new level. Now, it wasn’t simply a string quartet that was written a hundred and twenty years ago. It was a living, breathing piece of art, as vibrantly alive as the birds, mosquitoes, and crickets who lived in their eternal home along the Turkey River.