Issue No. 14: April, 2002

Publisher’s Notes by Fredrick Zenone

Personnel Notes

The 21st Century Music Director: A Symposium

Explorations in Governance and Leadership: The Philadelphia Orchestra by Paul V. Boulian

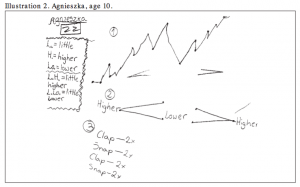

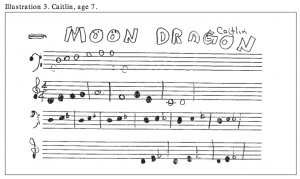

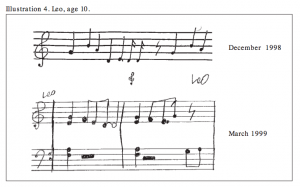

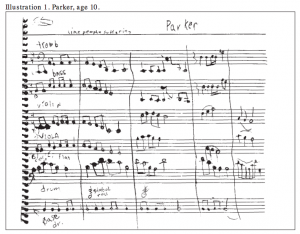

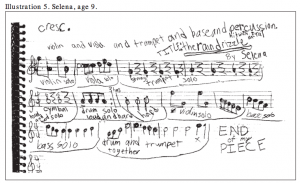

Children’s Creativity and the Symphony Orchestra: Can They Be Brought Together? by Jon Deak

Building Leadership in a Young Symphony Orchestra by Roland E. Valliere

San Francisco: A History of Long-Tenured Board Leadership

Organization Change

About the Cover…by Phillip Huscher

There is much attention given these days to the fact that the musical leadership in a large number of prominent North American orchestras is changing. The New York Philharmonic and the Philadelphia Orchestra have designated conductors who have previously led large American organizations. The orchestras in Atlanta, Boston, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Houston, and Minnesota have named music directors who are important musicians, although they have not previously been the artistic leaders of large American symphony organizations.

It seems reasonable to assume that in all those search processes, there was considerable discussion about how each organization defined and described the position of music director, and what combination of assets were needed to address the organization’s issues. For many of our symphony organizations, recent issues have included the place of the symphony orchestra in the community; the growth of the audience for symphonic music; performance of new and recent music; the current place of the arts in public education; and anxiety about our ability to fund our symphony institutions.

American symphony organizations are unique in the way they function. They are funded differently from those in other countries; their governance structures and responsibilities are different from those in other countries; and perhaps we feel somewhat differently about our roles and responsibilities in society. It is likely that decisions are made somewhat differently here than elsewhere. In the midst of all the artistic leadership change taking place in America’s orchestras, it is appropriate to ask what we want from our new artistic leaders.

In August 2002, the Boston Symphony Orchestra hosted a symposium at Tanglewood to ask important questions about the role of the music director in the orchestra of the 21st century. The Institute is pleased to publish the report of that symposium, as prepared by Thomas Wolf and Gina Perille of Wolf, Keens & Company. The symposium looks to be an important first step in a process the Institute hopes will become an ongoing discussion within and among symphony organizations. We use a constant term—symphony orchestra—to describe a constantly changing entity. It therefore is imperative to define the role of music director in ways that are appropriate for today’s orchestra organizations, as well as for those of the future.

Because we remain committed to fostering positive change in symphony orchestra organizations, it is with considerable pride that this issue of Harmony presents the report of the Symphony Orchestra Institute’s work with the Philadelphia Orchestra. The report, authored by Paul Boulian, represents the Institute’s work as part of a larger facilitated change initiative taking place within the Philadelphia organization. It details ways in which representatives of the orchestra’s constituencies examined governance, leadership, and professional development issues within the organization. The result is a set of recommendations to the orchestra’s board of directors.

The specific recommendations were designed for the Philadelphia organization. In reporting the recommendations, the Institute does not intend to put them forward as appropriate for other organizations. But we do hope the report can provide a structure to help other symphony organizations that want to examine their own thinking about governance and leadership.

When we think about the place of the American symphony orchestra as a community resource, it is inevitable that education comes quickly to mind. All our orchestras play concerts directed specifically toward young people. Sometimes those performances are didactic in nature, sometimes exploratory, sometimes entertaining. Jon Deak is a prominent American composer who, in one of his other lives, is a bassist with the New York Philharmonic. His music is widely performed and his unique, identifiable voice is one of his most remarkable gifts. He chose to try to make the symphony orchestra available to children in a new way. It is not very difficult to imagine that a composer would be sensitive to the creative process, but this composer imagined that he could guide young children through the creative process of writing music for the symphony orchestra. Along with his desire to have young children experience the joy of that creativity, he values them as composers and, as a result, they quite naturally trust that he understands their vulnerability as creators. When I read his story, my wish is to have been a child in the company of Jon Deak.

Site visits with supporting orchestra organizations have been a regular part of the Institute’s field program. These visits make certain we are familiar with current thinking and practices in the industry. About 18 months ago, I was invited to visit with the Cleveland Orchestra. At one point, while casually looking around the beautifully renovated Severance Hall, I wandered into the “rogues’ gallery,” the room in which the Musical Arts Association displays the portraits of past board presidents. I recognized the portrait of Ward Smith, about whom I have come to think as a model among symphony board presidents. There beneath the portrait, the term of his tenure was indicated. I thought it was a remarkably long term; he served as president from 1983 to 1995. But as I went around the room, it became apparent that a long term was the norm among Cleveland board presidents. It was the first time I had seen so dramatic a representation of a culture of long-term leadership in an American symphony organization.

It made a strong impression because, nearly always when I visit a troubled symphony organization, I find that tradition or bylaws have established a practice of short-term board leadership. We at the Institute resolved to look more deeply at the tenure issue. The result is the section in this issue of Harmony that puts forward the leadership-tenure culture of three organizations: two of long-standing prominence, and one which those of us with hindsight of a short 25 years might think of as a remarkable turnaround. All were asked to contribute to this issue

◆ We report the support and encouragement of the Institute’s work over the past 12 months by symphony orchestra organizations.

As I complete my first introduction to Harmony since becoming the Institute’s president in December 2001, I want to thank not only those who have generously contributed to this issue, but also the many colleagues and friends who have communicated to wish me well. The Institute is a work-in-progress—as are our beloved orchestras. My energy for the work is high, and I look forward to your input and encouragement.

Personnel Notes

Kathleen A. Byrne

We welcome Katie Byrne, who serves the Institute as communications specialist. Katie hails from Northbrook, Illinois, and holds her B.A. in English from Boston College. She served as an editor for two publishing houses in Boston for several years and has recently returned to Chicago.

Board of Advisors

Members of the Board of Advisors are active participants in or close observers of symphony orchestra organizations. They offer ongoing advice about programs, policies, and the general direction of the Institute’s work. Additionally, they foster greater awareness of positive organizational changes and advances in effectiveness within symphony orchestra organizations.

The 2002 Board of Advisors is composed of eighteen members, six of whom are new to the board and twelve who continue to serve. We extend our thanks to Carter R. Buller, Julie Haight-Curran, Justine LeBaron, and John David Sterne who completed their service in 2001.

We welcome the new advisors:

Carole Haas Gravagno

Carole Haas Gravagno is a vice chair of the board of directors of the Philadelphia Orchestra and chairs the education and community partnerships committee. She previously chaired the artistic and education committee.

She is active in civic and cultural affairs in Philadelphia and currently serves as president of the board of the National Liberty Museum and as vice chair of the Morris Arboretum and the People’s Light & Theatre Company. She sits on several additional boards, including the Philadelphia Chamber Music Society, the Settlement Music School, and Philadelphia Hospitality, Inc.

Carole holds a B.A. from Lenoir-Rhyne College in North Carolina and an M.Ed. from Temple University.

Joan Greabeiel

Joan Greabeiel is executive director of Orchestra London Canada. She previously served as director of finance for the Calgary Philharmonic and in a similar position with the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra. She also served the Edmonton Symphony as director of marketing and festival coordinator. In May 2002, she will become general manager of the Edmonton Opera.

Joan holds her bachelor’s and M.B.A. degrees from the University of Alberta and has a diploma from the Hochschule für Musik in Vienna, Austria.

William Helmers

Bill Helmers has been a member of the clarinet section of the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra since 1980. In addition to his work with the symphony, Bill performs with the Milwaukee Chamber Orchestra, and with Present Music, and teaches at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. He has also twice chaired the Milwaukee Symphony’s orchestra committee.

In the summers, Bill has been a member of the Santa Fe Opera Orchestra and has performed at the Washington Island Chamber Music Festival. He is also active in the performance and recording of new music; he gave the American premiere of John Adams’s clarinet concerto, Gnarly Buttons, in 1997.

Bill holds a B.A. from the Eastman School of Music and a M.M. from the Juilliard School. He also attended the Music Academy of the West, Tanglewood, and the Conductors’ Institute at the Hartt School of Music.

Karen Schnackenberg

Karen Schnackenberg is chief orchestra librarian of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra. She previously served in the libraries of the New Orleans Symphony, the Santa Fe Opera, the Oklahoma Symphony, and the Chamber Orchestra of Oklahoma City. She is also a violinist and performs periodically with the Dallas Symphony and other area groups.

Karen is an active member of the Major Orchestra Librarians’ Association and has served as that group’s president. For 12 years, she was classical music columnist for the International Musician, the U.S. trade paper for professional musicians.

She holds bachelor’s of music education and master’s of music in violin performance degrees from the University of Oklahoma.

Margery S. Steinberg

Margy Steinberg is an associate professor of marketing at the University of Hartford and also serves as executive director of the university’s Center for Customer Service. She consults in the areas of marketing research and marketing training with both corporate and nonprofit clients.

She has published and lectured extensively, and is an active member of the National Retail Federation, the Marketing Research Association Institute, the Connecticut Business and Industry Association, and the American Marketing Association.

Margy is a member of the board of directors of the Hartford Symphony Orchestra, which she served as president from 1996 to 1999. She also serves on the Boston Symphony Orchestra Tanglewood Committee and on the board of directors of the Greater Hartford Arts Council.

She holds a B.A. from Boston University and M.A., M.B.A., and Ph.D. degrees from the University of Connecticut.

Allison Vulgamore

Allison Vulgamore is president of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra. She previously served the New York Philharmonic, the National Symphony Orchestra, and the Philadelphia Orchestra. She began her career as a member of the first class of the American Symphony Orchestra League Fellowship program.

She is a trustee of Oberlin College in Ohio, and has regularly served on committees for the National Endowment for the Arts and the American Symphony Orchestra League. She is also active in civic affairs in Atlanta, serving on the board of the Midtown Alliance and as an advisor to the Boys & Girls Clubs of Metro Atlanta.

Allison holds a bachelor of music degree from Oberlin College Conservatory.

We extend thanks to the 12 advisors who agreed to continue their service:

Deborah R. Card

Deborah Card is executive director of the Seattle Symphony, a position she has held since 1992. She previously served as executive director for the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra and as orchestra manager for the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

She has been active in numerous music and arts organizations throughout her career. Deborah currently serves on the board of overseers of the Curtis Institute, as well as on the boards of the Seattle International Music Festival, the Association of Northwest Symphony Orchestras, the Downtown Seattle Association, the BH Music Center, and NPower, a Seattle-based organization providing technical support in the areas of technology and e-commerce to nonprofits nationally. She also serves as a faculty member for management sessions of the American Symphony Orchestra League’s Orchestra Leadership Academy.

Deborah holds her bachelor’s degree from Stanford University and an M.B.A. from the University of Southern California.

Jon Deak

Jon Deak is a well-known composer who is also associate principal bassist and creative education associate with the New York Philharmonic. His compositions have been performed at music festivals around the world and by major symphony orchestras and chamber groups throughout the United States. His Concerto for Contrabass and Orchestra was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

Jon is an avid mountaineer and is active in bringing new music to young people. He has taught in public schools in Denver and New York City and is currently developing and implementing a technique that allows elementary and middle-school students to compose directly for the symphony orchestra.

He attended Oberlin College, holds a bachelor’s degree from the Juilliard School of Music, and a master’s degree from the University of Illinois. As a Fulbright Scholar, Jon completed his graduate study at the Conservatorio di Santa Cecilia in Rome.

Douglas Dempster

Doug Dempster is Senior Associate Dean in the College of Fine Arts at the University of Texas, Austin. He previously served as Academic Dean at the Eastman School of Music and was founding director of Eastman’s Arts Leadership Program.

He has published extensively in the areas of philosophy of music and music theory, philosophical aesthetics, arts and the law, and the philosophy of language.

Doug holds a B.A. from St. Lawrence University, and an M.A. and Ph.D. from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

William Foster

Bill Foster is assistant principal violist with the National Symphony Orchestra, of which he has been a member since 1968. His son, Daniel, is principal violist with the National Symphony—wonderful testimony to the musicality of the Foster family.

Throughout his career with the National Symphony, Bill has been active in the overall affairs of the organization. He has served several terms as chair of the orchestra committee and has served on the artistic advisory committee. He has also served on executive director and music director search committees and on several board long-range planning committees. He is currently a member of the national Electronic Media Forum.

He holds a bachelor’s degree from the Oberlin Conservatory and a master’s degree from the Cleveland Institute of Music.

Valborg L. Gross

Val Gross is a violist with the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra. She has been an active participant on the team of musicians that developed the Louisiana Philharmonic into the only fully cooperative professional symphony organization in North America. She served as president of the board of directors during the 1997-1998 season.

Before joining the Louisiana Philharmonic, she performed with the Syracuse Symphony, New Jersey Symphony, Orquesta Sinfonica de Maracaibo in Venezuela, Florida Symphony, Santa Fe Opera, and the Aspen Music Festival. During summer months, Val performs with the American Sinfonietta at the Bellingham Festival of Music in Washington state.

She holds a bachelor’s degree from Vassar College and a master’s degree from the Manhattan School of Music.

Carolynn D. Loacker

Lynn Loacker is the immediate past chairman of the board of the Oregon Symphony Orchestra. She previously chaired the governance committee and served as a member of the executive committee.

She has been active in community service in Portland since she moved to the area in 1984 and has served on the boards of the Portland Zoo, the Franz Cancer Research Leadership Cabinet, and as a committee member for Women and Philanthropy. She is also active with conservation and wildlife organizations in the Pacific Northwest.

Anne Manson

Anne Manson is music director of the Kansas City Symphony, a position she has held since 1999. She previously served as music director of the Mecklenburgh Opera in London.

She has performed with symphony orchestras and opera companies throughout Europe, including the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, the London Philharmonic Orchestra, the Royal Scottish National Orchestra, the Ensemble Inter Contemporain, and the Grand Theatre de Geneve. In the United States, she has conducted the Washington Opera, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Houston Symphony, and the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra.

Anne holds her bachelor’s degree from Harvard University and trained at King’s College London and at the Royal College of Music on a Marshall Scholarship. She was also a Fellow in Conducting at the Royal Northern College of Music.

Robert H. Mnookin

Bob Mnookin is Williston Professor of Law at Harvard Law School. He is also director of the Harvard Negotiation Research Project and chair of the steering committee for the program on negotiation. He previously served on the law faculties of the University of California at Berkeley and Stanford University, where he also served as director of the Stanford Center on Conflict Resolution.

He has published extensively on the topic of conflict resolution and has mediated a number of landmark commercial disputes. Readers of Harmony are familiar with his group’s work with the San Francisco Symphony as published in the October 2001 issue. Bob has also served as a consultant to the Boston Symphony Orchestra concerning governance.

Bob holds an A.B. from Harvard College and an LL.B. from Harvard Law School.

Victor Parsonnet, M.D.

Victor Parsonnet is the Medical Director of the Pacemaker Center and the Director of Surgical Research at Newark Beth Israel Medical Center. He is also chairman of the board of the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra.

An accomplished surgeon and researcher and a pioneer in kidney and heart transplantation, coronary bypass surgery, and cardiac pacing, he has served on the boards of many professional societies and on the editorial and advisory boards of prestigious medical and surgical journals. He has published extensively and holds five patents.

Victor holds a bachelor’s degree from Cornell University and received an M.D. degree from New York University College of Medicine and Dentistry.

Michael Pastreich

Michael Pastreich is executive director of the Elgin Symphony Orchestra in Illinois. Under his leadership, the Elgin Symphony Orchestra has become Illinois’s second largest orchestra. During his term as an American Symphony Orchestra League Management Fellow, he interned with the symphony organizations in Louisville, Pittsburgh, and Indianapolis. He then completed service on the staffs of the San Jose Symphony, the New World Symphony, and the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra.

Michael holds a B.F.A. from Washington University in Saint Louis and completed studies as a Fulbright Scholar at Lahden Muotoiluinstituuti in Lahti, Finland.

Ronald Schneider

Ron Schneider is a french hornist with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. He has been an active participant in the governance of the Pittsburgh Symphony, serving as an orchestra representative to the board of directors and as chair of the orchestra committee.

He has taught at Penn State University, Duquesne University, and Chatham College and is an active participant in Pittsburgh chamber music groups.

Ron holds a bachelor’s degree from the Eastman School of Music and completed graduate work at Northwestern University.

Thomas H. Witmer

Tom Witmer is a member of the board of advisors of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. For the past several years, he has served as a catalyst and key participant in the orchestra organization’s Hoshin and related organizational performance programs.

Throughout his career, he has been recognized for his commitment to quality, business performance excellence, and entrepreneurship. From 1982 to 1998, Tom served as president and chief executive officer of Medrad, Inc., a Pittsburgh- based manufacturer of medical equipment. Prior to that, he served as president and chief executive officer of Union Carbide Imaging Systems.

Tom continues as a director of various corporate and nonprofit organizations, including the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh and four corporations.

The 21st Century Music Director: A Symposium

This report was prepared by Thomas Wolf and Gina Perille of Wolf, Keens & Company. The sessions were facilitated by Bill Keens. Grateful acknowledgment is offered to the funders that made the symposium possible: William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and David & Lucile Packard Foundation.

In August 2001, as reported at MusicalAmerica.com, Ronald Blum of the Associated Press wrote a story about symphony orchestra music directors. “Around the world, it is a season of farewells. At the end of this season, Seiji Ozawa, Christoph von Dohnányi, and Kurt Masur will leave the Boston Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, and New York Philharmonic, respectively, and Wolfgang Sawallisch will depart the Philadelphia

Orchestra after the 2002-2003 season.” Blum’s list of conductors changing in Europe included the Berlin Philharmonic’s Claudio Abbado and the London Royal Opera’s Bernard Haitink. If there was ever a time to take stock of the role of music directors in orchestras, this was the moment.

During the same month the article appeared, the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) convened a symposium at the Tanglewood Music Center to grapple with the question of the role of orchestra music directors in the 21st century. The topic had been prominent for the BSO ever since it began its own search for a music director to follow the quarter-century tenure of Seiji Ozawa. The Tanglewood Music Center—the BSO’s summer home and educational arm—had discussed the topic as well in thinking about its training programs for conductors. With the broader field of symphony orchestras increasingly focused on the issue, it seemed an appropriate time to encourage and document a discussion by a group of experts.

Tanglewood has also, throughout its history, been a place where people have come together to think about and discuss important issues relating to classical music. This symposium was an extension of that tradition.

Approximately 30 music directors, musicians, orchestra administrators, managers, trustees, and funders attended the two-day symposium. Co-hosts Peter Brook (BSO board chair), Mark Volpe (BSO executive director), and Ellen Highstein (director of the Tanglewood Music Center) spoke about the importance of the symposium and the reason for convening it.

Trends and Market Forces

There are various trends and market forces changing the way orchestras operate. A number of these are external to the organizations:

◆ Audience patterns are changing and, in many places, demand for the symphony product is down.

◆ There is increasing competition from other forms of art and entertainment.

◆ Evolving technology is increasing the options for the delivery of music both within, and especially outside, the concert hall.

◆ A changing urban landscape, with new demographics, calls for new roles and respon- sibilities for orchestra institutions.

◆ In many places, there is a greater focus on education and community concerns.

◆ Orchestras currently face great economic pressures. Some of the trends and forces shaping change are internal:

◆ Power is being redistributed within orchestra institutions.

◆ Musicians are playing many roles within their organizations, beyond the traditional ones of playing concerts.

◆ There is less reliance on traditional top-down authority and leadership.

These trends have the potential to alter the role of the music director, as well as the roles of others who have the responsibility of leading orchestra organizations.

One Size Does Not Fit All

The group acknowledged that there is no single response to questions about the role of the music director in the 21st century.

◆ Orchestras are not dealing with a single monolithic problem. Each is dealing with a different mix of challenges.

◆ The realities orchestras face vary according to their size, their character, and their communities.

◆ The role of the music director, and the way that role is perceived, will differ for major international orchestras, community orchestras, and those in between.

◆ Even when the external forces shaping orchestras and music directors are similar, the responses will vary widely.

For example, what is the music director’s appropriate role in responding to community concerns?

◆ For a major orchestra, the answer may well be that this is a minor part of the job. The role of music director in such an organization focuses on maintaining and building musical excellence at the highest level. The orchestra may require many things from its leadership in the area of community outreach, but generally this will not be the primary focus of its music director, who often does not possess, nor is willing to pursue, the proper grounding for this role.

◆ In a smaller orchestra, building musical excellence is also important. But the music director of a smaller orchestra must be more involved in such other activities as building community connections, meeting with the city council or the Rotary Club, or taking an active role in educational activities.

The Cult of Personality and Evolving Leadership

We live in a society in which the cult of personality is highly developed. The music director fills the role of public personality for an orchestra. That fact feeds a number of trends:

◆ Many conductors believe that they should build their careers and name recognition by appearing widely throughout the world.

◆ There is a perception of a shortage of star talent among conductors, and also that these individuals operate in a “seller’s market.”

◆ There is competition among orchestras and communities to secure the services of the top talent.

◆ There is little pressure for the music director to “stay at home” and build the orchestra institution.

◆ Many individuals hold multiple music directorships. ◆ There is a public perception that the music director is (or should be) the “leader” of the institution.

At the same time, there is a trend among orchestras to become more inclusive in the way they are managed, governed, and led and to develop new kinds of power-sharing arrangements. This participatory culture can cause confusion in an institution in which the music director is perceived, at least publicly, as the leader.

◆ Who is really in charge?

◆ What is the relationship among the music director, the executive director, and the board chair? Does this so-called three-legged stool really work?

◆ Can someone who is present in the community only 10 to 15 weeks a year really be the sole leader of the institution?

◆ What roles might musicians play, and what new power-sharing configurations are appropriate?

◆ Are musicians willing to assume the new roles that are being contemplated for them? As an example, do they really want to be involved in peer review of their fellow musicians?

This seems to be a time when internal relationships are shifting and must be defined institution by institution. The profile, expectations, and job description of the music director must be carefully worked out in relation to others in the institution and customized for each situation.

Training

The changing landscape has implications for training. Conducting students often receive inadequate preparation for the many roles, responsibilities, and expectations orchestras have for their music directors. Conservatories and other training institutions might address this issue, and several are beginning to modify the ways in which they prepare people for the field.

But there are challenges. It is absolutely essential for conservatories to concentrate on the musical elements of conductor training, which involves a lot of time. Conservatories cannot graduate people who are deficient in these areas, so artistry appropriately becomes the main focus of a curriculum. Conducting students must understand that musical excellence is a prerequisite for developing a career, and their teachers also want to focus on music. Even if conservatories were to provide ample opportunities to garner knowledge and experience beyond musical training, students often would not take these other areas as seriously while they are in school.

◆ One area is leadership. A music director needs to know how to inspire and lead 80 to 100 players and how to mobilize section heads and others in service of that goal. But leadership is not a central part of a conductor’s training.

◆ Another area is program planning.

◆ Others include dealing with the media, designing educational programs, and learning how to improve the level of orchestral playing through hiring, firing, promotions, demotions, and so on. Within the context of a unionized ensemble, the latter can be very sensitive.

◆ Familiarity with labor issues and understanding the overall financial structure of orchestras may also be important knowledge areas for music directors.

Most of this extra training will probably not happen in conservatories. Internships, on-the-job training, mentorships, and mid-career opportunities for learning are important. Much as lawyers who find that law school did not really prepare them for their professions, conductors (and musicians generally) may need ongoing programs of continuing education to address the real challenges they will encounter on the job. Experienced artist managers can play an important role in helping conductors understand and interpret the realities and mandates of the field. But there may be a need for more formal vehicles. Most major business schools have training for young and mid-career executives. Would something similar be appropriate for music directors, or is the making of a music director simply too idiosyncratic for any one formula?

What We Can Learn from History

Joseph Horowitz was asked to prepare for the symposium a history of the music director position in the United States. In looking at orchestras in Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York, as well as the Theodore Thomas Orchestra—the first full-time orchestra in the United States—Horowitz identified certain trends that were assets in orchestras of the past:

◆ Conductors stayed at home and built their ensembles artistically.

◆ Conductors served as missionary educators introducing audiences, often for the first time, both to the symphonic canon and to important new music. This music was not as widely available outside the concert hall as it is today.

◆ Conductors were regarded as the cultural leaders of their communities. This enhanced the institution’s visibility and gave it an important place in the life of the community that most orchestras do not occupy today.

Changes have occurred, and this profile of the music director no longer applies. A new structure is evolving. On the artistic side, the idea was put forward that musicians could be more involved in artistic planning. The use of a broader artistic staff, including artistic advisors and consultants, must be acknowledged as playing a larger role in supporting an often absent music director.

Musical Excellence

What is the place of musical excellence in the job description of a music director? Most agreed that it is the very core of the description, and that the fundamental responsibility of the music director must be building the musical excellence of an orchestral ensemble. Several participants who had been through music director searches recalled formulating broad profiles and job descriptions for new music directors only to realize that no one had all the desired attributes. Musical excellence, combined with real leadership ability, turned out to be the fallback and primary criterion.

One musician from a major orchestra recounted how, in the process of developing the ideal profile, desired attributes eventually gave way to this single requirement:

The committee convened and we discussed what we were looking for in a music director. The musicians wanted someone who would raise the artistic level of the orchestra even beyond what we are accustomed to. Board members were looking for someone who could walk into a room and galvanize donors to write bigger checks. Management wanted someone who would tend skillfully to personnel issues, planning seasons, and associated administrative tasks. Some people wanted a music director who would spend a lot of time in town working for the orchestra. Others said it should be someone who could communicate well in the community—perhaps an American. A few thought it might be nice to find a rising star whose stardom could grow to match that of the orchestra. But in the end, as we distilled the attributes down and when we looked at a list of 100 potential candidates, the list shrank rapidly as we decided the one most important factor we needed was a truly great musician. We could give up on a CEO, a community spokesperson, a fundraiser, but we could not give up on someone who could make music at the highest level—someone whose artistic excellence would propel the orchestra to new heights.

Two other orchestra representatives concurred:

A great conductor has the most inscrutable kind of skill, an elusive and special kind of thing. It is probably better and more important for him or her to be on the podium searching for musical truth than at the Rotary giving a speech.

We have to remember that a great conductor never stops studying and spends many hours each week with scores. It is not a situation in which one learns technique, artistry, and repertoire as a student and then the learning process is over. They are lifelong students of music.

Implications of the Musical Excellence Paradigm

If musical excellence is key, and if the growth of a musician/conductor is itself a life’s work, then there may be some obvious corollaries:

◆ The so-called “music director” may appropriately function more as a chief conductor than a true music director in many institutions, given the limited available time to attend to the myriad tasks and responsibilities required in the modern orchestra. This individual might be the one charged with preserving and enhancing musical excellence, while another person would take on the missionary role of outreach and education, as well as other functions.

◆ Given the realities of the field today, the individual will probably not be in residence for the majority of the season, thus further reducing the time available for extramusical activities.

◆ The power dynamics of an orchestra are complex, and the music director is not a CEO in the traditional sense. The perception of him or her as the single leader with total and exclusive authority must be corrected.

◆ The more extended responsibilities that one might want from a music director need to be shared among numerous individuals (assistant conductors, artistic administrators, musicians) including some who may not now be in the orchestra institution.

◆ If the mandate is musical excellence, then perhaps other things, such as giving the individual more rehearsal time, will need to change in order to make that goal easier to achieve.

Other Forms of Excellence

As the discussion of musical excellence progressed, many questions surfaced. What is the consequence of holding out musical excellence as the paramount criterion in choosing a music director? The financial investment an orchestra makes in a music director is generally considerable. Are there other returns they should seek for that investment? Should orchestras make investments in good halls, customer service, and community service, to name a few? The list of

desired attributes in a music director beyond musical excellence might also be long, and might include leadership ability, communication skills with the broader community, skill in educational programming and mentoring, and organizational management skills.

The conversation became heated when it was argued that large investments in marginal increases in musical quality might not be in the best interests of the institution because the money might be needed elsewhere, and that a diminishing number of people in orchestra audiences can even distinguish the differences between great and good. The response to this assertion was swift. According to one of the music directors present, “As soon as we start underestimating audiences, we are making a serious mistake.” One of the funders, in asserting a different point, cited recent research commissioned by the Knight Foundation that indicates that many audience members do not even list excellence of performance as a primary incentive for attending a concert. Others countered that people may think they cannot tell the difference, but often they can.

Certainly for every incremental improvement, an orchestra will have to increase its financial investment. Orchestras need artistic, financial, and institutional stability, and they should not aspire to a level of artistry that they cannot sustain. An orchestra must do the best it can with the resources it has, and it must face choices wisely and realistically.

The Commitment to Audience and Community

Audiences: It was suggested that in developing a profile for a music director, selection committees would be wise to consult more with audience members. The Knight Foundation-sponsored research cited earlier indicated that large portions of today’s classical music audiences have very little musical background. Further, the research indicates that there appears to be little correlation between audience members’ levels of enjoyment of concerts and their levels of musical training. Finally, audiences attend concerts for many reasons, only some of which relate to the singular high quality of the performance. If ticket sales are becoming a problem in many orchestra institutions, should there not be a clearer focus on how audiences can be better served? Might an investment in a music director who is less distant from audiences be more prudent in some cases (especially if musical excellence is still reasonably high)? Or is meeting audience needs someone else’s job?

The Community: This view was amplified by a funder who said that the musical quality of an orchestra is only one criterion used by many foundations in determining grants. This foundation, for example, is deeply focused on the orchestra’s role in the community, and its ability to reach out to a broad segment of that community. Perhaps this is not the music director’s job, though the community sees the music director as the institutional leader and so takes cues from the way that person behaves. Even if the music director should not be focused on community concerns, the question still comes down to resources—both financial and human. What kinds of resources will the institution devote to audiences and community? Is it more important to tour Europe with a well-known music director or to perform in local neighborhoods? In the end, it may depend on the orchestra and its priorities.

Broadening the Team

Another funder acknowledged the importance of both musical and nonmusical goals for the orchestra institution and spreading responsibility for these goals among a team of individuals:

Orchestras today clearly must have multiple goals, and they need to find multiple structures and various individuals to carry out these goals. Whenever you try to optimize on several characteristics, you won’t find someone who is A+ on all of them. Inevitably, if artistic merit has to be A+ for the music director, then you will need to find other ways to offload other functions. You don’t need to give them up.

Training and Career Development

What is the ideal training for a music director? A small subgroup from the symposium came up with an outline for discussion:

Artistry

◆ Study of instruments, piano,

◆ Composition, ear training,

◆ Repertoire, including opera,

◆ Score analysis,

◆ Singing (rhythm and pitch). It is important for conductors to be able to demonstrate to the orchestra players through singing.

Cultural literacy

◆ Contextualization of musical content, with high degree of broader cultural understanding (literature, history, visual art, architecture, theatre, etc.).

Physicality of conducting

◆ Study of movement,

◆ Gestural grammar.

Podium time Understanding orchestra operations and activities including:

◆ Labor issues,

◆ Personnel issues and how to manage them,

◆ The financial structure of orchestras,

◆ Education (adults and young people),

◆ The relationships among music director, management, and board,

◆ Fostering the idea of giving back to art itself.

Other

◆ Serving as an ambassador of an orchestra and a city,

◆ Dealing with the world of artist managers,

◆ Dealing with the media (print, TV, radio),

◆ Understanding the recording industry,

◆ New media and its potential impact on the distribution of music,

◆ Intellectual property issues,

◆ Interview skills.

Not all of this training can occur in a conservatory or even while an individual is in his or her “student” period. But there are various forms of preprofessional training possibilities including:

◆ Workshops,

◆ Apprenticeships,

◆ Internships,

◆ On-the-job mentoring. (Mentoring, though rare, could be offered both by individual conductors, from an orchestra itself, and from others in the business.)

Two additional suggestions were made about connecting training institutions more closely to orchestras:

◆ Leaders of musical training institutions should be in contact with those who actually run symphony orchestras, just as law professors tend to be well- connected with firms that do the hiring.

◆ Orchestras might look to conservatories to provide cover conductors from their graduating classes. A young person coming in to cover for several weeks would learn a great deal, and the orchestra would gain a talented young person as a potential replacement in an emergency.

Recruitment and Selection

Another small group discussed an appropriate process for recruiting music directors.

Formulating a vision for the orchestra

◆ The process must begin with the orchestra clarifying its vision for the future. How does it see itself in five to ten years, and how should a new music director play a role in achieving this vision?

Process of selection

◆ The process of selection must be clearly articulated so that everyone in the orchestra institution (and those outside who are interested) understands it.

Questions to be answered might include:

◆ Will there be a selection committee? How will it be composed and who will decide who serves? What is its role?

◆ Who will make the final decision?

◆ Who will be consulted in the process and when?

◆ How will opinions be solicited?

◆ What role will musicians have—not only those on the selection committee, but others as well? (Would a conductor be hired whom the majority of musicians did not want?)

◆ Will all candidates be required to guest conduct?

◆ What information will be shared with press and public, and when?

◆ Who will be spokesperson?

◆ Who will meet with the candidates and when? (This often cannot be an ironclad rule because some candidates will not allow themselves to be official candidates until the job is offered so interviewing has to be a quiet process, often with a small subgroup).

Selection Committee

◆ The committee is generally composed of a mix of musicians, trustees, and management.

Questions to be answered might include:

◆ Are musicians appointed by peers or selected in some other way?

◆ How are decisions made (by majority vote, consensus)?

◆ How often will the committee meet?

Job description and profile

◆ The job description describes the tasks and responsibilities associated with the position, as well as the reporting structure.

◆ The profile describes the attributes of the person to be hired.

◆ Residency requirements (if important): For some orchestras, specifying the minimum number of weeks of residence, as well as conducting, may be important.

Special challenges

◆ An orchestra is always looking (or should always be looking) for its next music director even when it is not in a search. This means that the selection of guest conductors has a special importance. Sometimes the current music director is not helpful in this process for obvious reasons.

◆ The press can be a detriment to a smooth process, spreading incorrect speculation, scaring off candidates, or undermining a “normal” conducting opportunity by raising the stakes so high that the candidate does not perform well.

It was generally agreed that musicians today are increasingly driving the process of music director selection and that their strong involvement can be a genuine benefit to orchestra institutions.

Institutional Structure and Authority

A third group dealt with the question of institutional structure and authority.

◆ How should orchestras be led and by whom?

◆ How does the music director fit in?

The group posed six templates of organizational structure as follows:

Musician-run orchestras. This model is found mostly outside this country in such cities as Vienna, Berlin, and London. The Orpheus ensemble in the United States, though a chamber orchestra, has attributes of this model. So do many orchestras that have been restructured from bankrupt predecessors, such as those in Colorado and Louisiana (though these have evolved toward more

traditional structures as they have moved away from their initial entrepreneurial phases to those of maturing businesses).

Conductor as CEO. This was a more common structure in the early days of orchestras in the United States. The conductor was the autocrat who commanded the orchestra, had complete artistic control, and worked with a board and manager who supported him. Birmingham, England, had something similar more recently, though does not today.

Artistic Director or General Director. This model is more common in opera companies or smaller organizations such as chamber music festivals. A single person at the top has both artistic and administrative people reporting to him or her. The individual can be a conductor, administrator, or even a scholar. In an orchestra, a general director might hire all the guests,

including a chief conductor, though perhaps not make the personnel decisions among orchestra members (this might be the role of the chief conductor).

Music Director with additional artistic support (creative chair, dramaturg, artistic administrator). With the trend toward absentee music directors, there is increasingly a need for additional people to support the artistic planning side of orchestra operations. This is particularly the case when complex, thematic, and/or highly creative programming is involved.

Three-legged stool (board, music director, executive director). This overused metaphor describes what has been the most common structure for American orchestras in recent years. It suggests a shared power arrangement among the volunteer head, the administrative head, and the musical head. There are often tensions—especially between the two latter positions—over who really has authority to make decisions that straddle the line between artistic and administrative.

Four-legged stool (musicians added into the mix). With musicians assuming greater responsibilities, the conventional three-legged stool appears to be evolving into one in which the musicians play an increasingly prominent role. Their involvement in the selection of music directors is an example of this trend.

Which of these models makes most sense for orchestras today and how does the music director’s role influence that structure?

“ With the trend toward absentee music directors, there is increasingly a need for additional people to support the artistic planning side of orchestra operations.”

◆ If the music director does not have the time to tend fully to the artistic side of the operation (especially if he or she is in residence only a short time each season), then musicians should have a strong voice in artistic policy and procedure. It should never be assumed that the music director speaks for the musicians.

◆ Wholly musician-run orchestras, on the other hand, have proven to be largely unstable organizations in the United States. The demands of fundraising and administration require specialized expertise and a lot more time than musicians can or are willing to give, generally speaking.

◆ Non-musician board members in musician-run organizations worry about the relationship between authority and accountability. (Will the musicians assume legal liability for their actions?) There is also sometimes a misalignment between empowering and enabling (i.e., are musicians qualified to do the jobs that the power structure gives them?).

◆ In the three-legged stool model, orchestras have often found a misalignment between authority and expertise. Those with the legal authority to make decisions—trustees—often know the least about the business.

◆ In the four-legged stool model, there are some inherent tensions in making “labor” a part of the governance and decision-making structure, but it has been accomplished successfully in many organizations.

If orchestras are to make the transition from the three-legged to four-legged stool model, which many at the symposium endorsed, several things have to happen:

◆ The process must be intentional. Orchestras cannot drift in the direction of musician empowerment, but must be explicit in how they will accomplish the change.

◆ The music director must understand and buy into the change and the structure.

◆ The process must be accomplished slowly through education and commitment to change on the part of all parties.

◆ The orchestra must be personalized and humanized.

◆ Change is effected more smoothly by finding ways to use the talents of musicians more creatively (e.g., through service conversion, on planning committees).

◆ There must be clear definitions of responsibility and authority.

What Needs to Change

Change is inevitable in the orchestra field, though it occurs slowly. Participants identified four areas of change that are critical to the 21st century world of music directorships:

Orchestras must develop profiles for their music directors that directly relate to the vision, needs, and capacity of their organizations. There is no single profile of the perfect music director. An individual is ideal only in relation to a specific orchestra in a specific community. The cult and prestige of a star personality is alluring. But orchestras should ask themselves the key questions: Who are we? Who do we want to be? What can we realistically achieve? What sort of person can help us realize our aspirations?

The job descriptions and expectations for music directors must be ambitious but realistic. During the symposium, participants discussed two rhetorical questions. Do we expect too much from our music directors? Do we expect too little? Both are often true. The expectations that many have built up about music directors are unrealistically molded by a time when music directors stayed at home, built their orchestra institutions, had complete artistic control, and did not have to deal with today’s harsh financial realities. We cannot have the same expectations today. But we must expect music directors to fulfill the responsibilities established by a mutually agreed job description, and we should expect the field to provide music directors with the proper preparation to do so.

The structure and authority arrangements within the orchestra must continue to evolve. Music directors are often treated as though they have enough time and a large enough mix of talents to lead an institution in multiple areas. Even in the artistic realm, this is often not fully possible. Roles and responsibilities need to shift. Musicians are taking on new and expanded roles and responsibilities in some institutions. But orchestras must also be open to the fact that new categories of people may be required in their organizations to get the job done.

The training of conductors must change. In particular, post-conservatory training must prepare conductors for the brave new world of music directorships in 21st century symphony orchestras. In the future, opportunities and structures may be required to fulfill these needs that go well beyond the training opportunities that now exist.

The symposium began with representatives of the Boston Symphony Orchestra discussing the inevitable changes that will occur as a result of the departure of a long-term, charismatic music director. As the symposium ended, other participants acknowledged that their institutions also face the inevitable uncertainty that comes with turnover in the music director’s position. What will the future hold for these orchestras? It is too soon to tell. What is clear is that changes are inevitable, and to the extent that orchestras can shape these changes, they will be blessed with stronger institutions in the decades ahead.

Participants

The Boston Symphony Orchestra and Tanglewood Music Center express their gratitude to those who participated in the symposium. Titles and organizational affiliations of the participants were current as of the date of the symposium.

J. Thomas Bacchetti, executive director, Colorado Symphony

Melanie Beene, program director, The James Irvine Foundation

Carmelita Biggie, committee member, Helen F. Whitaker Fund

Alan Black, principal cellist, Charlotte Symphony Orchestra

Paul Brest, president, The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation

Peter A. Brooke, chairman, Boston Symphony Orchestra

Gary Burger, program director, Community Partners Program,

John S. and James L. Knight Foundation

Peter Cummings, chairman of the board, Detroit Symphony Orchestra

Roberto Diaz, principal violist, The Philadelphia Orchestra

Jo Ann Falletta, music director, Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra and Virginia Symphony

Miles J. Gibbons, Jr., executive director, Helen F. Whitaker Fund

Nancy Glaze, director, Arts Program, David & Lucile Packard Foundation

Marian A. Godfrey, director, Culture Program, The Pew Charitable Trusts

Ellen Highstein, director, Tanglewood Music Center

Joseph Horowitz, historian, writer, artistic consultant

Edna Landau, managing director, IMG Artists

Keith Lockhart, conductor, Boston Pops; music director, Utah Symphony Orchestra

Michael Morgan, music director, Oakland East Bay Symphony

Lowell J. Noteboom, chairman of the board, Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra

Joseph Polisi, president, The Juilliard School

Joseph Robinson, principal oboe, New York Philharmonic

Don Roth, president-elect, Aspen Music Festival and School Robert Spano, music director, Brooklyn Philharmonic Orchestra; music director designate, Atlanta Symphony Orchestra

Roland Valliere, executive director, Kansas City Symphony

Mark Volpe, managing director, Boston Symphony Orchestra

Karen Wolff, dean, School of Music, University of Michigan

Edward Yim, director of artistic planning, Los Angeles Philharmonic

Explorations in Governance and Leadership: The Philadelphia Orchestra

Over the last several years, members of the Philadelphia Orchestra community—board, staff, musicians, and volunteers—have invested many hours in discussion and analysis of their governance and leadership

processes. Beginning in the fall of 1997, representatives of the Symphony Orchestra Institute engaged groups and individuals from the organization on topics of organizational performance and relationships among key constituencies.

In 1999, the board determined that it was time to revisit the organization’s strategic plan. As the conversations progressed, leaders of the constituencies agreed that the planning process itself should reflect a growing view that multiparty leadership was necessary for success. With that thought in mind, the planning process began in earnest in 2000.

Rather than having a designated committee develop a long “to-do” list for the next few years, planning- process leaders focused on four conceptual topics:

◆ Mission, vision, artistic direction,

◆ Venue,

◆ Marketing, and

◆ Governance, leadership, and professional development.

Work groups (representing all four constituencies) were formed for each topical area, with each group composed of at least 12 members plus a skilled facilitator. It was also determined to be wise to have a 16-member “integration group,” composed of representatives of the work groups and the process facilitators, in order to ensure that the recommendations of the separate teams would be aligned for the overall organization.

Symphony Orchestra Institute representatives worked most closely with the governance, leadership, and professional development group (GLD), and it is that story we detail here.

Because the GLD’s recommendations were likely to have significant impact on the organization’s long-term thinking, and because constituency leaders needed to have high stakes in the recommendations, the chair of the orchestra members’ committee, immediate past president of the volunteers, current and immediate past board chairs, and president of the orchestra all agreed to serve on this committee.

Laying the Foundation

Early in the process, the GLD decided it needed to understand why its assigned topic was important. Committee members reached the following conclusions:

◆ The years ahead hold significant challenges that will require the best thinking of all members of the Philadelphia Orchestra community.

◆ The most effective response to challenges requires unified leadership and multiconstituent agreement.

◆ In the current organizational environment, effective decision making and action is difficult, due to governance or leadership concerns.

◆ All agreed that they had a strong desire to create new and more effective ways of working together.

The committee also recognized that it had been given a formidable charge to improve the overall governance process of the organization, as well as that of each constituency. Committee members had also been asked to examine and improve the relationships among and within constituencies, the quality of overall group leadership, and the professional development of constituency members.

As readers should well expect, this charge was more extensive than any committee could address in six months, so the group focused its attention first on the governance process, agreeing that thoughts about leadership and professional development would follow.

An additional part of laying the foundation involved agreeing to a basic flow of work. With guidance from the facilitators, the committee agreed to the following:

◆ It would first determine the scope and boundaries of its work. All participants needed to understand what was included in the work and what was not. This step included defining terms.

◆ They would then develop a governance, leadership, and development fact base for the organization as a whole and, separately, for each constituency.

◆ They would work through the following steps sequentially for each area:

❖ Develop shared values and beliefs.

❖ Develop strategies for achieving those values and beliefs.

❖ Develop designs for action to carry out the strategies.

❖ Create a set of integrated, comprehensive recommendations.

Establishing Scope, Boundaries, and Definitions

In establishing the scope of its work, the committee understood very quickly that by agreeing to address governance of the organization overall, as well as in each constituency, they were extending accepted thinking about the topic. For example, when one says the word “governance,” most individuals immediately think “board of directors.” However, in a multiconstituent organization such as a symphony orchestra, the governance processes within individual constituencies should have great influence on the governance process of the board itself.

The committee identified several subtopics which members agreed needed to be addressed:

◆ Current and future roles of the orchestra members’ committee, the board and its executive committee, board committees, the volunteer association, staff and executive management, and the media company.

◆ Current and future roles of key individuals, including the orchestra members’ committee chair, the board chair, the president of the orchestra, the president of the volunteer association, and the music director.

◆ Decision making within and across groups, including consideration of how input is and should be sought, who is and should be involved, and what processes are currently and should be in place.

◆ The values of the various constituencies and the level of agreement within and across groups as to whether the values needed to be modified in order for the culture to evolve in a more effective way.

◆ The leadership of key individuals, including the music director, both within and across constituencies.

◆ Working relationships, including consideration of ways to develop trust and respect, and to improve relationships over time.

As they worked to locate the boundaries, committee members agreed that such important topics as collective bargaining and organization performance would be addressed tangentially, but not as core governance topics. They also agreed to working definitions of five terms: governance, leadership, professional development, beliefs, and values.

The process of defining terms provoked some lively discussion. For example, the committee did not come to immediate agreement on an operational definition of governance. Members agreed early on that governance is not about having musicians on the board, nor is it about the decision-making process at the board level alone. They ultimately agreed that governance is about what items require decisions, where, how, and when decisions are made, and who is involved in making decisions. With scope and definitions now established, the committee turned its attention to developing a fact- base.

Developing the Fact-Base

Effective strategic planning requires agreement about facts, although when the topic is qualitative (governance), what constitutes a “fact” may itself be debatable. The GLD approached this phase of its work by asking the representatives of each constituency to develop facts relating to their particular subgroup. This process required several meetings and involved assembling information that was readily available, asking questions to learn more, reporting, and discussion. The committee agreed that when all members of a constituency shared a belief, it would be viewed as a “fact.”

When the fact-base was complete, it was summarized as themes that appeared across several constituent groups. These were considered to represent a pattern of behavior throughout the organization.

Examples of facts as developed by the GLD include:

◆ There exists a high level of interest and energy to be involved in the organization’s activities in a meaningful way. However, many of these desires are not currently being fulfilled.

◆ Many constituency members do not view their participation in and input to the organization as valued.

◆ The constituencies do not currently view one another as partners, but there is a strong desire to develop strong partnerships and working relationships.

◆ In many cases, the current governance process assures that there will be reaction on the part of those groups that were not involved in the initial thinking and decisions.

◆ Many of the issues that exist within and across constituencies are due to the lack of good processes, knowledge, and skill in addressing very difficult and complex topics. They are not due to a lack of will to do a good job.

◆ There are structural and process challenges unique to each constituency.

◆ There is currently not a shared vision, set of values, and strategy within and across constituencies to serve as a coalescing force.

With the fact-base in hand, the committee turned its thinking to the process it would use to develop strategies and designs for action. The facilitators suggested a rigorous process that involved working to establish key values and shared beliefs, and only then turned attention to concepts, strategies, and designs for action.

Key Values and Shared Beliefs

Organization development professionals have demonstrated repeatedly that one way to create alignment of a team relative to the future is to establish agreement in two areas:

◆ The key values, or what the group sees as important to them relative to the future.

◆ The shared beliefs, or what the group holds to be true about the topic.

The GLD developed a set of key values related to governance that the entire organization should hold:

◆ Trust,

◆ Shared participation and broad involvement,

◆ Respect among constituencies,

◆ Commitment to artistic integrity,

◆ Maintenance and growth of financial viability,

◆ Synthesis and integration of the parts,

◆ Pursuit of excellence,

◆ Customer service, internal and external,

◆ Meeting the needs of all stakeholders, and

◆ Diversity.

At first blush, these values might seem obvious. But a rigorous planning process explores current values and contrasts them with ones desired for the future. For the Philadelphia organization, the current values and those desired were, in some cases, at odds. For example, everyone agreed that the organization had currently and should continue to have “a commitment to artistic integrity.” But discussions of participation, meeting the needs of stakeholders, customer service, and diversity revealed ongoing actions that contradicted this value.

The discussion of values was often difficult. However, it provided great insight into the organization’s culture and served as a springboard as the group began

to develop a set of beliefs that would guide “outstanding” governance for the organization.

Governance Beliefs

The process of establishing a set of beliefs about governance began with each committee member formulating his or her own set of beliefs. The committee then convened and reviewed all entries. The full set of beliefs was categorized and culled for duplication, and then discussion began. Over many hours, committee members worked to reach consensus and to determine the implications of pursuing each belief. When the group had agreed to a full set of beliefs, they tested their work for consistency and discussed the implications of the total set.

The agreed governance beliefs fell into three broad categories:

◆ Beliefs that focused on the overall organization.

◆ Beliefs that focused on the constituencies and the ways in which they work together.

◆ Beliefs that focused on each individual constituency.

Overall Organization Beliefs

The GLD agreed to five beliefs that would serve to guide the overall organization:

◆ Within a mutually agreed time frame, all decisions regarding direction, strategy, vision, and mission will be made through consensus-based processes that meaningfully involve all constituencies.

◆ A permeating and shared vision will energize what we do and assure that we can be outstanding.

◆ If we buy into our mission/vision at the highest personal level, we will create will and passion across the whole organization.

◆ All constituencies will respect the musicians’ legal right to “organize.”

◆ The total organization will address the great majority of issues, with a limited number of issues to be addressed in a traditional labor-management context.

The discussions that led to this set of beliefs was extended and often difficult. As an example, to reach agreement on the first belief, committee members needed to resolve several paradoxes and challenges. The board holds fiduciary responsibility for the organization, yet the staff has administrative and operational responsibility.

Current operational processes created conditions by which several constituencies became involved only after fundamental decisions had been made, which often led to polarization. Decisions were often challenged after the fact or defended as part of their presentation. The core question became: could each constituency agree to involve the others earlier and more fully in the decision-making process? In the end, the committee’s answer was “yes.”

Adoption of the last two beliefs also had deep philosophical and practical implications for all constituencies. While there was recognition of the reality of “organized” musicians as a Philadelphia Orchestra constituency, a number of GLD members were uncomfortable with that fact. Ultimately, the group worked through the tensions and agreed that the organization must have the systems, processes, and leadership to work in its actual environment.

Beliefs for Constituencies Working Together

The GLD also adopted five beliefs to guide the ways in which the constituencies work together:

◆ We will make decisions that are informed by what is “best” for the total institution.

◆ We will make better decisions and will be better able to implement these decisions by having broad involvement and participation.

◆ If people are better informed, and are able to learn about and have input into decisions, they will have a greater “buy-in” to those decisions.

◆ We are a more effective organization if each group has well-defined processes for making decisions and ways to communicate decisions within and across constituencies.

◆ When speaking to the outside world, all constituencies should speak with one voice.

The formulation of this set of beliefs also came only after extensive discussion. For example, agreeing with the first belief created two new accountabilities:

◆ To ensure that all constituencies know what is going on. That would involve developing processes to attack the exclusivity that currently existed within and across constituencies.

◆ Ensuring that decisions are made in the best interest of the whole organization.

No longer could a constituency plead ignorance, choose not to be included, or exclude others. And no longer could a constituency make decisions that did not take into account the organization as a whole.

Beliefs for Individual Constituencies

The discussion that led to the development of the beliefs for the constituencies collectively also uncovered the need to recognize that three of the constituencies are legal entities with their own charters and bylaws. That fact gave rise to the development of the following:

◆ Each constituency maintains its unique integrity, and all other constituencies will recognize that integrity.

◆ Each constituency will have decision topics that are unique and confidential.

As they discussed the ramifications of making decisions in the best interest of the whole organization, committee members recognized that this might be interpreted as usurping the integrity of an individual constituency. They agreed that under no circumstances should that threat exist. These final two beliefs recognize the tension that must exist within and across constituencies. The GLD agreed that tension, when addressed productively and positively, created excellent outcomes.

Overall, this set of beliefs recognizes that an effective organization must have excellence in information sharing, involvement of participants beyond their core constituencies, and respect for the confidentiality and uniqueness of each group as a legitimate entity.

New Governance Strategies

As we turn to a discussion of governance strategies and designs for action, readers are reminded that three additional strategic-planning work groups were simultaneously addressing the topics of mission, vision, and artistic direction; venue; and marketing. Before the GLD began its further work, the 16-member integration group convened to reflect on the work of the four strategy teams and to ensure that there was basic agreement with each group’s tentative conclusions. There was consensus that the direction being set by the GLD was correct, and the group was charged to develop specific, actionable ideas to implement the beliefs.

Beliefs form the roots of strategy. If one believes something to be true, one can develop a strategy to implement the belief. From the strategy, one can develop specific designs for action.

Over a period of several months, committee members developed six fundamental strategies. They believed that these strategies would have profound and lasting impact on the Philadelphia Orchestra.

Create systems and structures to ensure multiconstituent involvement in and information for fact-based decision making within constituencies and across the total institution.

GLD members acknowledged that in the current environment, information- sharing and decision-making processes were neither systematic nor structured. Further, working from fact—especially shared facts—was not a common practice. This strategy implied a desire for significant change.

Build common decision-making and conflict-resolution processes within and across all constituencies.

Common language and thought processes enhance the ability of groups to reach agreement, especially on difficult issues. Using identical tools for decision making, discussion, and conflict resolution gives groups the ability to work on the content or substance of differences. Committee members believed that this strategy would be required as the Philadelphia Orchestra organization addressed complex challenges in the future.

Identify individuals with governance and leadership expertise. Develop and improve their capabilities. Nurture and develop future leaders in all constituencies.

Committee members agreed that, in general, the constituencies did not have effective succession plans and had not made it a priority to develop effective future leadership. They agreed that in order to move the institution forward, this strategy was needed for the overall organization, individual constituencies, and current and emerging leaders.

Create structures for regular information sharing and for participation in decision shaping by appropriate, broad cross-departmental or organizational groups. Create visibility to the organization of the projects and efforts that are in motion.

The committee agreed that formal processes should be put in place to ensure that information was shared more on a “right to know” basis and less on a “need to know” basis. This implies volunteering information about ideas being considered or in motion and reduces reliance on the grapevine or “fishing expeditions.” Decision-shaping involvement implies that while every group may not be involved in every decision, there will be an awareness of what is being considered “before the concrete hardens.”

Create a minimum number of groups to complete the work of the organi- zation effectively.

This strategy underscored the committee’s recognition that a proliferation of groups would tax the organization’s resources and ultimately backfire. They agreed that the groups should be focused and not redundant. For example, an overall artistic committee might replace the current musician, staff, and board artistic committees.

Develop methods and processes to assess and assure the performance of individuals and groups.

Many organizations experience situations in which leaders do not meet the expectations of individuals and groups. Meeting expectations is a multidimensional process: the incumbents must understand the expectations; the expectations must be shared both among incumbents and those who have an interest in incumbents’ performance; the means of assessment against expectations must be understood; and the process must be mutually confirmed. In other words, performance assessments can be truly fair only if everyone understands the rules of the game. Committee members agreed that individual constituencies and the organization as a whole needed a more formal process for assessing performance, providing performance feedback, and providing developmental opportunities.

Members of the governance, leadership, and professional development committee understood that these strategies would test the will of the organization to make effective and meaningful change. They also recognized that successful implementation could not rest with one or two constituencies or with one or two key leaders.