The Typology of Intellectual Capital

The Typology of Intellectual Capital 1

Intellectual capital (IC), intangible resources of organizations, was suggested in the previous article as a possible area to manage for orchestras to consider. IC is made up of human capital, such as competencies and individual attributes; structural capital, such as routines and processes that coordinate the orchestras purpose; and customer or relational capital, the relationship the organization has with its customers and external constituents (i.e. stakeholders). This article will continue and examine the types of intellectual capital found in the nine month case study of two community orchestras.2 The focus of this article will be the identification of human capital and structural capital both of which are a part of a community orchestra’s stock of resources.

Dimensions of Human Capital

In the previous article, human capital was defined as consisting basically of skill and know-how. Human capital, which pertains to belonging to individuals, spans a vast array of attributes: competence, performance in jobs, efficiency of training, learning abilities, abilities, education, previous training, previous job experience, employee trust towards the organization, perceptions of organizational climate, motivations, career development, job satisfaction, and job retention. Drawing from the above descriptions human capital can be framed through an organizational behavior lens of participation, motivation, and personal goals. To make human capital a manageable application for orchestras, a general taxonomy provides a common set of traits that are: competency based, motivated based, and goal fulfillment based.

|

Human Capital |

Attributes |

| Competency | Skills and know-how |

| Motivation | Trust, loyalty, and knowing others |

| Goals | Enrichment and purpose to work |

Source: Adapted from Mesa (2010) Journal of Intellectual Capital 3

Dimensions of Structural Capital

Structural capital represents formal routines, informal routines, processes, ways of doing work, common practices general to an industry, practices unique to the organization, organization structure, workspace, and organizational culture. German sociologist, Max Weber, defined three basic elements of an organization which are useful in allocating types of structural capital: authority structures, labor divisions, and things that coordinate work and practice. In essence, this triad, called social structure, can be identified as social artifacts. Artifacts in that they are essential to getting work done (think of decisions, processes, and common things that coordinate our work) and social in that people engage and use these things everyday in their work.

|

Structural Capital |

Attributes |

| Social Artifacts | Authority, labor division, coordination |

Source: Adapted from Mesa (2010), Journal of Intellectual Capital 4

I used the above in the course of collecting case study data towards identifying what makes up IC in community NPO orchestras.

Comments on Collecting Case Study Data

A brief note is in order regarding the types of data collection I used in the case study. Field observations, interviews, and surveys were used in gathering data. I used field observations to first glean what could be identified as the dimensions of human capital and structural capital. The purpose of this method was to immediately identify manifestations of human capital and structural capital merely by observing. I also reviewed the orchestra web sites for information about the concerts, members, and importantly mission and purpose.

Field observations have their limits. I had to discover individual motivations and reasons for participating in the orchestras. For this task, interviews were used to mine out what participants thought, felt, and believed as being part of the orchestra. As a summary of the general scope of interview questions, I asked participants to describe their perspective of the rehearsal process and how they contributed to the whole. I asked them to explain how they use their instruments and how others in the orchestra contribute towards the whole; and I asked what constitutes success in meeting the orchestra’s mission. All questions focused on grappling with identifying the attributes of human capital and structural capital—intangible resources crucial to the organizations purpose and function.

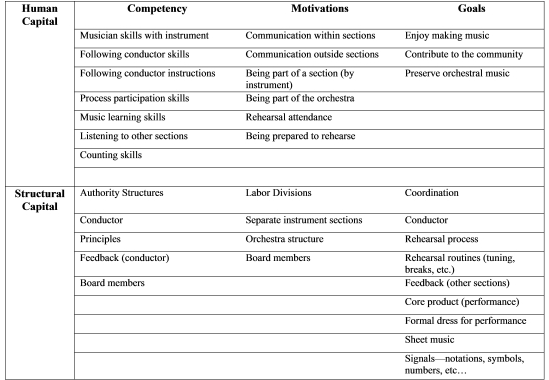

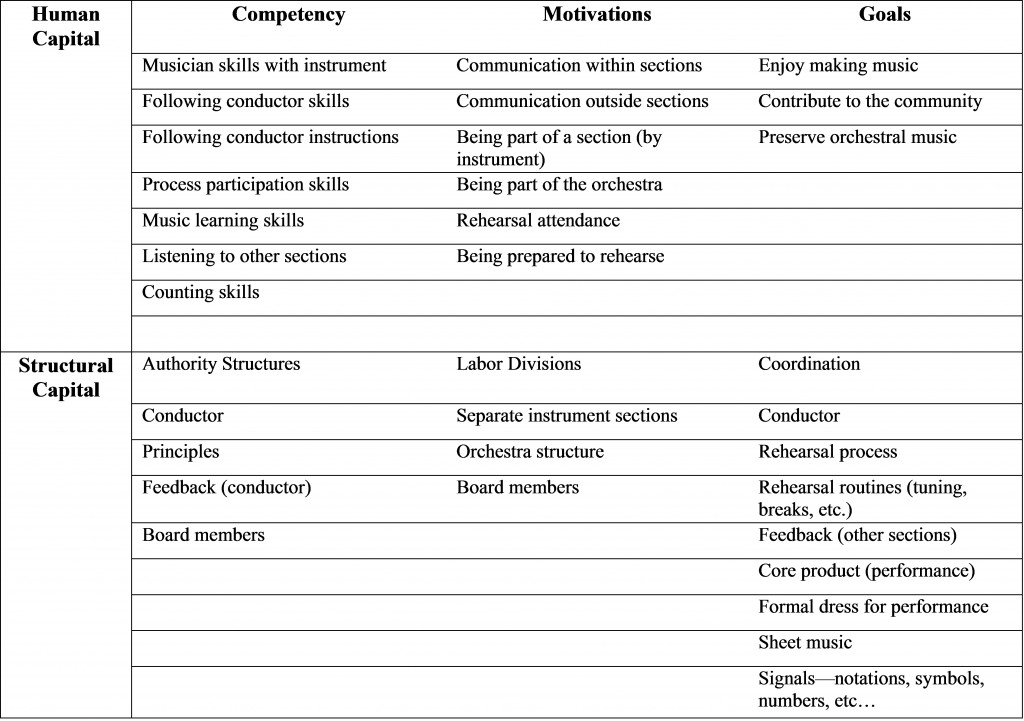

Stravinsky posits that finding contrast in music is readily easy to find. Discovering the familiar, however, is more challenging.5 Sifting through pages of field observation notes and interview responses, contrast immediately jumps out. Finding the familiar threads and themes, though, are what yield value towards identifying the IC resources of the orchestras. Interpreting observation and interview data required using pattern analysis—finding common threads that reflect the dimensions of human and structural capital identified above. Table I lists the basic human capital components of competencies, motivation, and goals.6 Also included is structural capital with attributes of authority, labor division, and how work is coordinated.

Table I: Community Orchestra Human Capital and Structural Capital

Source: Adapted from Mesa, (2010), Journal of Intellectual Capital 7

Identified Human Capital and Structural Capital

Managing and leading in an NPO community orchestra, largely made of volunteers, means understanding the dimensions of motivations, aspirations, and identities of its members. The mix of largely volunteers in NPOs makes them inherently more complex and difficult to manage than for-profit entities. An IC approach links the social nature of an NPO community orchestra’s mission with the mix of volunteers and unique resources.

Human Capital

Leveraging the most of skills and techniques people bring into the orchestra needs to be done within the context of why people participate and what shapes their motivations. It’s important to understand why a member feels the way they do about being a part of the orchestra. These are issues and questions of identity. Recognizing how people perceive the orchestra’s purpose and how it functions is just as crucial. Participants also have certain goals about being in the orchestra; knowing those goals and linking them to participating in the purpose of the orchestra can yield a greater cohesiveness of a diverse group of volunteers.

Motivations and goals of participants as human capital are sources of both why individuals are part of the orchestra. They provide the source as to why individuals may or may not be suited towards added tasks in the organization. Initial identification of human capital in motivation and goals suggests musicians enjoy being part of the orchestra allowing them to do something for the community. That “something” was preserving music for future generations, for current family and friends, and the community. Curiously, though, I found participants couldn’t state or even clearly identify the mission of their respective orchestras.

“I don’t know what the mission is. I guess it’s to bring culture and music closer to home. But I love doing it.”

Several statements point towards the enjoyment of making music, being part of the group, and the “duty” of contributing something to the community. Motivations and goals are important towards understanding what will make the organization most productive and towards the organization’s ends. Volunteers in NPO community orchestras are passionate about their craft. They participate with the intent of making a difference to others. When such aspirations are met, individuals generally will continue to participate.

Summary:

- 1. Individual motivations drive musician’s participation in the orchestra.

- 2. Individual goals and orchestra goals: do they align or are they different? How and where are they different?

- 3. Trust and loyalty of members are essential to the community orchestra and provide cohesion and consistency.

- 4. Individual skills, varying in range, can still be leveraged given motivations and goals for the individual shape and are shaped by the orchestra’s goals.

Structural Capital

The orchestra, by virtue of reflecting a written score, has separate instrument sections being a part of social structure. Most interestingly, though was the evidence that pointed to separate sections and motivations about being a part of the orchestra. Conversations were predominantly within sections and rarely did a different instrument section interact consistently with another instrument musician. Musicians identify within being a part of the orchestra by being a part of the section. One interviewee said:

“It’s our section; it’s what we play; it’s what we do. Other sections play different instruments.”

I found that structural capital was identified as being routines, processes, and reference points with an example being the conductor. These reference points facilitate coordination within the rehearsal processes. When I asked musicians what’s most important to them during rehearsals, a couple of answers stand out as being characteristic.

“…the conductor’s time management, how he works with individuals and places them in the whole puzzle. By following the conductor I have a good idea that I’ll be with the rest of the group.”

Structural capital here is made up of sections, a conductor, the organization structure, and processes that give life to IC that requires constant attention and guidance. What’s needed is guidance of both human and structural capital since they are inherently human activities.

Summary:

- 1. Being part of a specific group within the whole is important.

- 2. Coordination, particularly from an authority, is central to the community orchestra.

- 3. Processes and routines are the bulk of community orchestra activity.

Conclusion

While both human capital and structural capital have been identified, a more important question drove the case study over the nine months: How is IC used in community orchestras? Answering that fundamental research question would yield a framework on leading and guiding the leveraging of IC as a resource. In the next article, I’ll provide how human capital and structural capital are interrelated which suggests to leaders an understanding on how to guide human capital and structural capital.

1 Title adapted from chapter 4 of Stravinsky’s Poetics of Music,(1974); Harvard University Press.

2 This article series is adapted from my article “The composition of intellectual capital in non-profit orchestras” in the Journal of Intellectual Capital, 2010. Modifications particularly in table content and complete findings are reflected in this article.

3 Mesa, William B. (2010), “The composition of intellectual capital in non-profit community orchestras”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 11 No. 2 Special Issue IC and Non-Profits in the Knowledge Economy.

4 Mesa, William B. (2010), “The composition of intellectual capital in non-profit community orchestras”, Journal of Intellectual Capital,Vol. 11 No. 2 Special Issue IC and Non-Profits in the Knowledge Economy.

6 For greater detail on what makes up human capital and structural capital, please refer my article in the “Journal of Intellectual Capital”.

7 Mesa, William B. (2010), “The composition of intellectual capital in non-profit community orchestras”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 11 No. 2 Special Issue IC and Non-Profits in the Knowledge Economy.

No comments yet.

Add your comment