The Phenomenon of Intellectual Capital in Community Non-Profit Orchestras

The Phenomenon of Intellectual Capital in Community Non-Profit Orchestras1

Over the span of nine months, I conducted an in-depth case study of two comparable community non-profit orchestra organizations. My aim in the study was to essentially identify what constitutes the knowledge resources or intangible resources found in community orchestras and how are they used. What I found were the essential resources and creative people that represent what leaders should guide rather than merely manage. This article will describe the basic characteristics of these “invisible resources”, also known as Intellectual Capital (IC) and how it can serve as a strategic resource for community orchestras and professional orchestras.2

Two community orchestras in the Denver, CO metro-area, were the participants in the case study. Both orchestras were comparably similar with respect to the following: number of musicians; the mix of individuals that comprise the board; approximately 6 concerts a year, a 9-month season; and each orchestra performing in a performance hall that holds approximately 200-300 attendees.

NPO Community Orchestras

Understanding the significance of how IC is a resource for organizations, particularly NPOs (like community orchestras), means recognizing the significance of what is at root of what motivates volunteers in the NPO or community orchestra. Why do community orchestras exist?Why do they perform?Community orchestras exist to do their part in preserving orchestral music. They do so for their community and for future generations. In fact, community orchestras act out what Peter Drucker argued should be the very purpose of all non-profits: to change human lives and thus contribute to human flourishing. Drucker called non-profits (NPO) “human-change agents”.3

A leading researcher in how NPOs can leverage IC, Eric Kong, tells of the need for NPOs to identify their intangible resources and use them to their advantage.4 And if community orchestras are to act out their purpose they must do so with a level of excellence in light of thriving in a knowledge economy where music has taken on the characteristics of a commodity displacing an experience that enriches lives.

In a review of the Symphony Orchestra Institute literature (over 8 years of articles, opinions and studies) I found a recurring pattern that community orchestras are an important piece in the preservation of orchestral music. Additionally, members of community orchestra are motivated to participate because they just enjoy making music and want to participate with the group. As such, the community orchestra is an important human-change agent. While the study is on community orchestras and not the professional flag-ship orchestras that represent the icon of classical music, they are an important part of preserving orchestral music. Community orchestras are well situated to preserve classical music for the following reasons: (1) members of the orchestra are part of the community; (2) community orchestras are in the community rather than downtown; (3) tickets for a community orchestra performance cost less than for a professional orchestra; (4) the orchestra is the community’s. Emphasis is to be placed, however, that community orchestras play a part in preserving orchestral music; they are not THE basis for the future of preserving orchestral music. Rather, they work in tandem with the remarkable performances of live orchestral experiences provided by professional orchestras. Coupled with the motivation that members just enjoy making music, we have two suggestions to what constitutes intangible resources in community orchestras.

The Relevance of Intellectual Capital in Orchestras

Like any organization, orchestras have a pattern of recurring issues. Indeed, these issues are not permanently solvable, but require the constant attention of thoughtful participants and leaders as does a garden requires careful attention through cultivation. Three of the major issues that emerged during my examination of the SOI Harmony archives are: social structure problems, organizational culture divisions; and the difficulty of maintaining strategic intent. Recent articles in Polyphonic.org attest to the excellent tools of cultivation in addressing these issues.

A principal means to address problems in NPOs and orchestra organizations alike has been to apply the templates of for-profit models of organization structure, resource management, and organizational change. While these models do provide insights into how NPOs can be better managed, NPOs are also uniquely different in resource structure, patron (customer) structure, and management structure.Moreover, NPOs, such as community orchestras, provide a service to the community where organizational performance cannot be fully measured in terms of revenues or expenses. As mentioned, orchestras operate to preserve orchestral music; they work to make it accessible to a community; they perform music so that people can experience it a deep and contemplative level; and they perform music as an alternative to the current stream of entertainment options.The mix of employees in NPOs and community orchestras, varied funding resources, and limited funding contributes towards the complexities unique to the NPO community orchestra and professional orchestras. As such, for profit models can fall short towards informing NPOs and community orchestras on how to manage resources and lead people.

IC provides an alternative to strategically managing resources and guiding creative personnel for community orchestras that serve as human-change agents. IC, as Thomas Stewart of Fortune magazine defines it, represents organizational resources that create wealth through the investment and cultivation of knowledge, information, intellectual property, and experience. IC basically is classified into three components: Human Capital; Structural Capital; and Customer or Relational Capital.

Intellectual Capital

Human capital represents a set of “competencies”. For example, human capital can represent skill sets in employees or know-how, abilities, education, and training. But it can also encompass “what” or “type” characteristics like the quality of employees, efficiency of training programs, or learning abilities. From a reporting and cost stance, human capital can be defined as employee expenses, training expenses, productivity, and efficiency. Human capital, then, can be a set of “competencies”. Defining the range of competencies will be dependent on the type of organization and to what purpose human capital is to be leveraged.

For a community orchestra, there are varied elements of human capital that may contribute value to the organization or are supportive of the orchestra as a whole. Loyalty and motivations are also important for NPOs and community orchestras alike since it represents the longevity of competence provided by the volunteer/employee to the organization’s current resource mix.

Structural capital includes organizational structures, organization designs, work flow, processes, routines, authority structures, and varied types of labor. Organizational culture can also be a part of structural capital as it provides an underlying meaning to why and how certain processes take precedence over other processes. Also, structural capital represents the very routines and processes of which individuals (those holding the human capital dimension) participate.

Like human capital, structural capital can vary from organization to organization. In fact, it should have some degree of variation since organizations have a history of specific decisions, by certain individuals, with a certain endowment of resources. Thus, structural capital for a community orchestra can be a basis of managerial importance since leaders should know the ways of work indigenous to the organization that ultimately create the final product, or in this case, concerts.

Relational capital represents the organizations relationship to customers, patrons, stakeholders, funding entities (for NPOs), and the like. In a basic sense, relational capital is what the organization makes of its relationship with its environment, industry, community, and customer. Organizations interact with their constituencies, but the level of what the organizations receives and what it provides is rarely measured.

Summary of IC

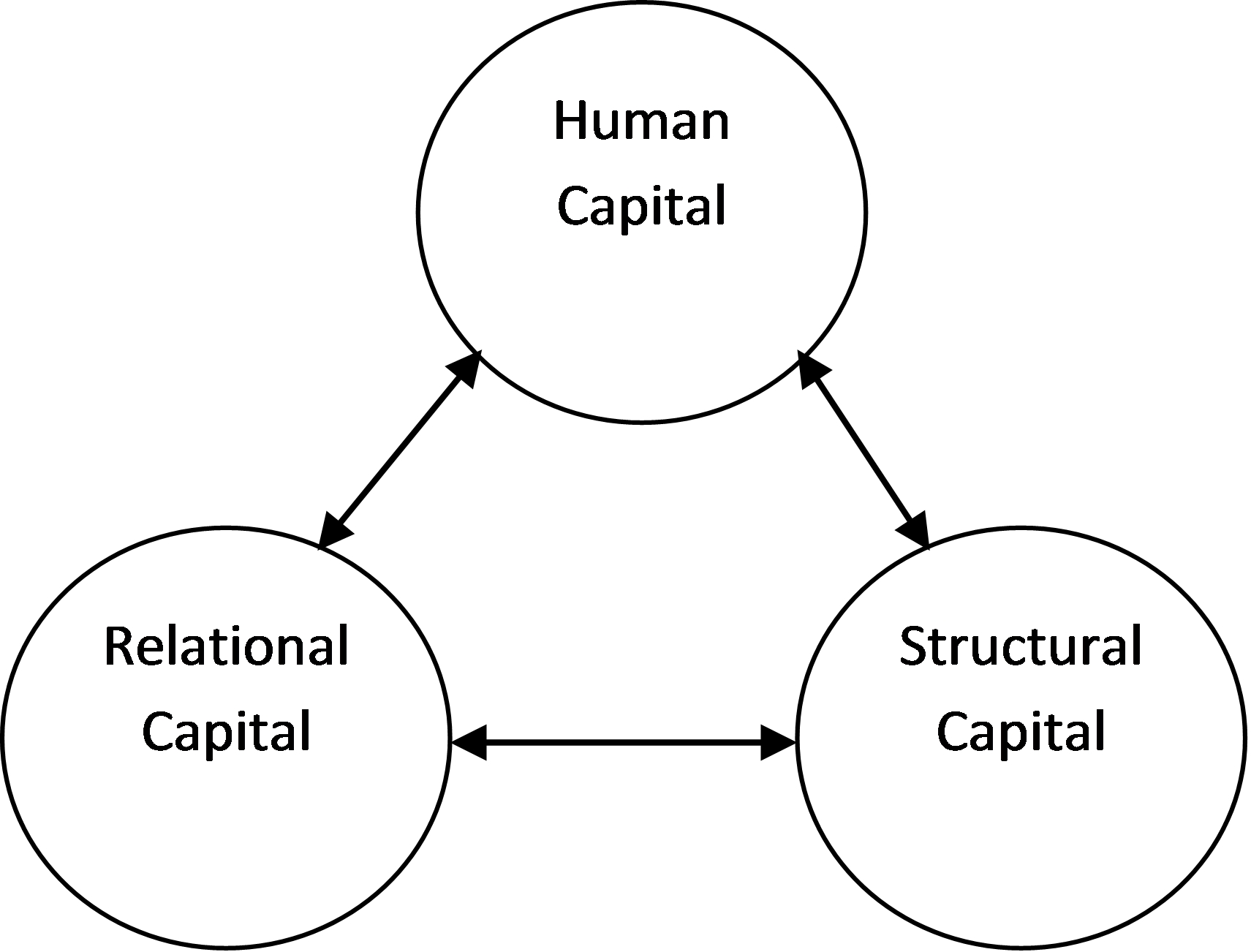

The following diagram provides a simple map of the interrelatedness of IC as a construct for leading and managing.

Note that it’s important to recognize that IC is made up of separate components, but all are interrelated. For example, human capital, while distinct in its attributes of “competencies”, needs to be understood within the context of structural capital and relational capital. This is the case for each component of intellectual capital—each represents a specific part of IC, but is also inseparably related.

The next article will provide the findings of what constitutes IC in community orchestras.

1. Title adapted from chapter 2 of Stravinsky’s Poetics of Music, (1974); Harvard University Press.

2. This article series is adapted from my article “The composition of intellectual capital in non-profit orchestras” in the Journal of Intellectual Capital, 2010. Many modifications particularly in table content and complete findings are in that article. Full detail can be accessed in the scholarly article.

4. Kong, Eric. (2007), “The Strategic Importance of Intellectual Capital in the Non-Profit Sector”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 8, No. 4, pp. 721-731.

5. See Kong, Eric (2006), “The development of strategic management in the non-profit context: intellectual capital in social service non-profit organizations”, International Journal of Management Reviews, Vol. 10 No. 2, pp. 281-299.

6. See Boaz’s excellent findings on the “Symphony orchestra organizations in the 21st century” at http://www.esm.rochester.edu/iml/prjc/poly/harmony/11/Orchestras_21st_Century.pdf.

No comments yet.

Add your comment