Canadian Perlustration

In my relatively brief tenure as Director of Symphonic Services for the AFM Canada, I have had the opportunity to visit orchestras from Halifax, Nova Scotia, to Victoria, British Columbia, and I have to say that the Canadian orchestral community represents the diversity of the national culture. We have internationally renowned major symphony orchestras, chamber orchestras, baroque ensembles, opera and ballet orchestras, contemporary music ensembles, training orchestras, youth orchestras, and community orchestras. As in the U.S., symphonic music here is thriving and slowly moving forward despite a challenging funding environment.

For example, as many of you may be aware, one of our fine orchestras, the Kitchener-Waterloo Symphony, has been in crisis this past month. I am happy to report that the threat of bankruptcy has been averted and operations will continue.

The Kitchener-Waterloo Board of Directors and musicians ratified a new four-year collective agreement in September 2006. Shortly afterwards, the KWS musicians were told that the accumulated deficit, combined with poor ticket sales, had brought about an immediate cash-flow emergency. If ignored, this would force the organization to cease operations at the end of October.

As a result, the orchestra embarked on an ambitious fundraising campaign to raise CA$2.5 million by October 31st. The city rallied behind the orchestra, and to date CA$2.3 million has been raised, mostly through individual donations, and the campaign continues. Consequentially, the musicians have agreed to take an immediate 15% pay-cut.

It is worth noting that KWS is a unique situation. The problems there go back to the acrimonious dismissal of Music Director Martin Fischer-Dieskau in November 2003. The controversy garnered significant media attention, including front-page stories in the regional daily newspaper, The Record, for over a year.

Canadian Operating Environment

The arts in Canada suffered funding cuts in the late 1990s. There were numerous financial problems which led to bankruptcy threats, strikes, and lock-outs. The Canadian orchestral community, through the leadership of Orchestras Canada (the Canadian equivalent to the American Symphony Orchestra League), began a comprehensive analysis of the situation through a project called Soundings.

The project identified four main orchestral organizational issues: governance, artistic development, community relationships, and capitalization. The content of the report was intended to inspire dialogue and assist the orchestral community in addressing these issues in a collaborative manner with a view to finding common solutions. A number of long-term strategies were recommended. They are structured around five modes of activity: Advocacy; Assembly and animation of best practices; Research; Training and professional development; and Other initiatives.

Following is an outline of the areas of recommendations:

1. Advocacy

1.1 Adequate core federal and provincial funding

“First and foremost, what is needed is a commitment by the government to adequate, stable, multi-year funding for the sector as a whole.” (Canadian Conference of the Arts- Bulletin 19/04.)

1.2 Tax Incentives for Philanthropic Giving

1.3 Cross-Sectoral Advocacy

1.4 Increased Municipal Funding

1.5 The Correlation between Music Education and Academic Achievement

2. Assembly and Animation of Best Practices

2.1 Establishing Core Principles and Shared Values

2.2 Improved Internal Communication

2.3 Implementing Governance Procedures

2.4 Musicians and Governance

2.5 Hiring and Nurturing Music Directors

2.6 Performance Presentation

2.7 The Correlation between Financial Health and Community Value

2.8 Diversification of Activity

2.9 Successful Media Strategies

3. Research

3.1 Market Research

3.2 Research and Development of the “Intervention Model”

3.3 Research and Development of the “Sustainable Multi-Purpose

Orchestra Model”

4. Training and Professional Development

4.1 Music Directors

4.2 General Managers

4.3 Musicians

4.4 Musicians, Management and Boards

5. Other Initiatives

5.1 General Management Development

5.2 Organizational Models

Implementation of these recommendations has been slow. Orchestras Canada suffered a funding cut from the Canada Council and has had to re-examine its mandate. Following is an excerpt from the Report of the Chair to the Orchestras Canada Annual General Meeting last June which describes the change in focus of the organization:

“The last several years have seen an evolution and refinement in the strategic direction of Orchestras Canada, and the pace of this evolution has accelerated in 2005-06. Through the considerable efforts of staff and board members this year, we have set out what we believe is a workable future direction for members’ approval today, one that provides the optimal delivery model for relevant programs and active services to Canada’s orchestral community, within sustainable financial resources.

This major overhaul has been required for a number of reasons. The amalgamation of the Association of Canadian Orchestras and Orchestras Ontario into Orchestras Canada in 1997 resulted in a carryover of objectives and responsibilities which, in hindsight, we believe contributed to the dilution of OC’s efforts. The Soundings report of June 2003, which documented the significant issues facing Canada’s professional orchestras, made over thirty specific recommendations for action by OC.

Restructuring of the OC organization was undertaken in September 2003 to provide an operational plan whereby OC could address the findings of Soundings. The financial forecast that supported the plan depended not only on continued government support, but also on developing new government and private revenue sources. By March of 2005, we realized that this plan was not sustainable. The responsibilities to the existing diverse membership base were significant. Our need to develop new sources of funding to provide the additional services and programs identified in the operational plan of September 2003 called for new approaches and further staff, which in turn further diverted OC’s focus from its core service commitment.

We grew concerned that OC was becoming less effective in fulfilling its mandate, and that concern was shared by OC’s principal operational funders. We realized that it was time to further rethink our direction, and we looked to develop a “modest plan, well executed”. At weekend meetings in October 2005 and January 2006, the board and staff redefined OC’s mandate in terms of members, core services, and programs.

The proposed membership is now concentrated on professional and semi-professional orchestras, overhead costs of the organization have been substantially reduced, and we have started to focus our networking and communications efforts on caucuses within the membership, using both face-to-face meetings and the technological means at our disposal.”

Funding

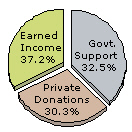

Funding for Canadian orchestras is almost evenly divided between government, individual, and earned income sources.

Orchestras in Canada depend on government funding from municipal (local), provincial (state), and federal governments. A recent comparative report by Orchestras Canada shows that orchestras with budgets of over CA$1 million depend on earned income for 37.2% of budget, private donations for 30.3% and government support for 32.5%. Federal support comes through the Canada Council for the Arts, by way of grants awarded through a peer review process.

The Canada Council for the Arts is a national arm’s-length agency created by an Act of Parliament in 1957. According to the Canada Council Act the role of the Council is “to foster and promote the study and enjoyment of, and the production of works in, the arts.” To fulfill this mandate, the Council offers a broad range of grants and services to professional Canadian artists and arts organizations in dance, interdisciplinary and performance art, media arts, music, theatre, visual arts, and writing and publishing. It also promotes public awareness of the arts through its communications, research, and arts promotion activities. The Council has suffered from chronic under-funding.

After a strong, unified advocacy campaign from the entire arts community in 2005, the major federal political parties agreed to substantial increases in Council funding. But alas, we had a National election which brought the current Conservative government to power. They have decided to reduce and delay the promised funds, much to our communal frustration.

Employments Status

Employment status is an interesting topic of discussion in Canada. In some orchestras the musicians are considered to be employees but in others they are considered to be self-employed independent contractors. An orchestra’s budget size makes little difference in determining status. There are even a couple of orchestras were there is a core of salaried employee musicians, supplemented by self-employed musicians.

There are pros and cons to each status. Employees are limited in the amounts they can deduct from their taxes for instruments, but are eligible for Employment Insurance (known as Unemployment Insurance in the U.S.) in the off season and Worker’s Compensation if they are injured. Employee orchestras also have an easier time negotiating benefits into their collective bargaining agreements, such as supplemental health and dental insurance.

Self-employed musicians can deduct more items from their taxes, but are ineligible for Employment Insurance or Worker’s Compensation. Currently the AFM Canadian Office is working with the Canadian government on initiatives to raise the instrument deductible for employee musicians and to have Employment Insurance and Worker’s Compensation made available on some level for self-employed musicians.

There was a period of time when the Canada Revenue Agency (the Canadian equivalent to the Internal Revenue Service) tried to change the status of some orchestras from self-employed to employee in an attempt to collect back employment taxes. The sudden cost nearly brought about the demise of the Thunder Bay (Ontario) Symphony, and it caused a panic throughout the industry. Recent tax court rulings seem to restrict the Canada Revenue Agency from initiating this kind of exercise in the future.

Training Tomorrow’s Musicians

Canada has numerous opportunities for young musicians aspiring toward orchestral careers. Each summer the National Youth Orchestra gathers talent from all over the country for intensive residences followed by a concert tour. The Academy Orchestra in Hamilton functions much like the New World Symphony in Miami by providing mentored, on-the-job training.

The Royal Conservatory system in Canada provides systemized training and evaluations for young musicians from beginners to very advanced players. In Quebec, there exists a similar French-language Conservatoire that has produced many excellent musicians who perform in orchestras in that province. Universities from coast-to-coast boast excellent performance faculties, with many instructors drawn from the local professional orchestra.

Health Care

Canadian collective bargaining deals with supplementary health care items, which comprise a much smaller part of their orchestra’s budgets as compared to peer ensembles in the U.S.

One major difference between U.S. and Canadian orchestras is the issue of health care coverage. Before coming to the Toronto Symphony in 1986, I was for seven years a member of the Jacksonville Symphony. Having dealt with HMO forms and rules, I can honestly say that I prefer the Canadian universal health care system. Some American musicians performing in Canadian orchestras have complained about wait times for service and have not felt that the quality of service was the same as in the U.S.

This has not been my personal experience. My family has always received prompt, professional treatment. There is great comfort in knowing that medical care is available without hassle and without having to examine your bank account. While U.S. health care is a major item in negotiations and a huge organizational expense, Canadian bargaining deals with supplementary prescription, dental, and non-covered health items. These supplemental health care issues comprise a much smaller and more stable part of an orchestra’s budget.

Broadcasting

Broadcasting in Canada works differently than in the U.S. Our national broadcaster, the Canadian Broadcasting Company (CBC), transmits live concerts from across the country for broadcast throughout all of Canada. The AFM-CBC agreement calls for a specific amount of money to be spent on AFM musicians for these broadcast endeavors. This results in most professional orchestras receiving nation-wide air play.

The fees for CBC broadcasts are based on the number of times a concert, or portion of a concert, are played over a specific number of years. The rates for Canadian musicians are generally higher than for U.S. musicians performing U.S. broadcasts. Over the last few years, the numbers of concert broadcasts have decreased and there is fear that this trend may continue.

Compensation & Season Length

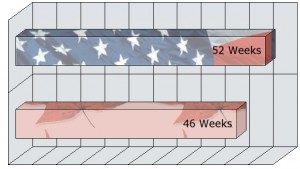

Canadian jobs tend to pay less than American jobs and that holds true for orchestral jobs. There are no 52-week seasons in Canada. The longest seasons are 46 weeks, and only two orchestras fall into that category: the National Arts Centre Orchestra in Ottawa and the Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal.

Weekly salaries in these orchestras are considerably lower than comparable U.S. ensembles. As a consequence, a significant number of talented musicians migrated southward in the past. There are American musicians, as well as other foreign nationals, in orchestras throughout Canada. Our “international” auditions truly are just that. Once an audition has gone to the International level, there is no preference given to Canadian candidates.

Conclusions

Despite the many challenges, the Canadian orchestral industry is moving steadily forward after a time of crisis. Orchestras are pursuing interesting educational initiatives and reaching out to younger adults and ethnic communities. A tour of orchestra websites across the country reveals interesting programs, excellent soloists, and fine conductors. Canadian cities are blessed with talented musicians who have put down roots, raised families, and greatly enhanced the artistic and educational life of their communities.

No comments yet.

Add your comment