Breaking the Sound Barrier: The Sphinx Organization and Classical Music

I would like to thank everyone at Chautauqua for inviting me to be here with you today representing the Sphinx Organization, of which I am the Founder & President and which I am proud to say has had the opportunity to partner with the Chautauqua Music Festival for over five years!

Ashley Montagu was one of the great humanists and intellectuals of our time. His research and writings helped launch or contribute to significant social movements, including the emancipation of the disabled through his book The Elephant Man, and the women’s movement through his book The Natural Superiority of Women.

He also had a huge impact on the issues of race and how it was considered in the scientific world when he published Man’s Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Race, which fought the growing popularity at the turn of the century of the idea of scientific racism. However, despite these great contributions to the elevation of the human race, the reason I mention such a man today is that he is quoted with words that touch a chord with me and my own life experiences.

The deepest defeat suffered by human beings is constituted by the difference between what one was capable of becoming and what one has in fact become.

When I hear those words, I think to myself, what shall I consider of those whose accomplishments not only meet expectations but exceed what anyone might have thought them capable of?

As I share with you my story and the work of the Sphinx Organization, I ask you to consider the accomplishments of so many musicians, many of whose achievements have gone unrecognized for far too long. I will also share a poem or two that I have written that reflects the topic or period in my life that I am discussing, as I feel that the artistic word can often share more with less than mere prose. I hope you will indulge me.

I have a rather unusual history, which I think would have made it quite difficult for anyone to even remotely try to determine what I might be capable of becoming. Certainly by any statistical norms, being born a bi-racial baby on September 11, 1970 to an un-wed white mother in a small village outside of Monticello NY, and being immediately given up for adoption, did not set the stage for the highest expectations in terms of my future capabilities. So, what could have taken place that brought me to be here on this stage before you this morning? Well, without going into too many details of my background, I do want to give you a snapshot of how I came to be standing here today as it defines the work that I do everyday.

I was born to an African-American father who was a Jehovah’s Witness and a white Irish-Catholic mother in 1970, when interracial marriage was still illegal in several states. Given society and other pressures at the time, my mother was forced to give me up for adoption. I was then adopted at the age of two weeks by a white Jewish family in New York City. By the age of 13, curiosity had taken hold and I began what was to become an almost two decade-long journey in search of my birth parents. For those of you who may not know, current laws make it next to impossible for an adoptee to locate their birth parents.

So it is all the more surprising then when, after all my fruitless efforts, I was reunited with them about five years ago at the age of 31 through the website adoption.com. Not only were my parents together but I was to find that they had eventually married and that I had a full sister. We have since had the most amazing relationship, and my sister now attends my alma mater, the University of Michigan. People sometimes ask me why I care so much about diversity and why I have dedicated my life to pursuits that further that end. I have the easiest response to that question: “I am a black, white, Jewish, Irish Catholic, Jehovah’s Witness who plays the violin. I am the definition of diversity. I don’t have a choice but to do what I do.”

When I was five years old, my (adoptive) mother, who was an amateur violinist, became motivated to play her instrument again by Nathan Milstein’s recording of the unaccompanied Bach Sonatas & Partitas. Her practicing inspired me and as a result, I took a great interest in the instrument and began vigorously studying myself. I was also very lucky to have the opportunity to study with Vladimir Graffman as my first teacher. He was one of the great Russian teachers and taught the likes of Josef Gingold, who became one of the great violin teachers in America. I wrote a brief poem about my time with Graffman and called it My First Teacher.

Mr. Graffman was old,

Russian immigrant.

His apartment was brown, I remember,

I was only seven, it was East Side, mid-town.

He’d always say, you no talk you play.

He was dedicated

With my talent evident. He would sit at the big black grand piano,

Ejecting praise, criticism like a little Hobbit,

I’d correct the mistakes quickly, muttering,

He would question my practice hours sincerity.

He’d always say, you no talk you play.

I was Black,

Boy, that was different.

After Lalo was concluded, his offerings complete

Anguishing, I gauged his satisfaction,

rarely recognizing his mood.

Passing the bar meant one of those candies,

my pick of color even,

From that crystal jar sparkling on the side table,

oasis amongst the Earthen tapestries.

He’d always say, you no talk you play.

I’d loosen my bow, pack my violin,

Music and sugar succulent.

More often than not, savoring,

I’d return home with orange tongue, my favorite flavor.

Sliding the rickety gate shut,

as I pulled the elevator lever,

always returning to the lobby late.

That ride almost as fun as the Bartok duets;

There was no practice time to prepare for when he died.

That time I would have complied.

He’d always say, you no talk you play.

I remember sitting in Carnegie Hall when I was 8 years old listening to Isaac Stern perform. The impact that experience had on me and the sense of awe it built in me about music has stayed with me all these years. However, I do not recollect seeing Sanford Allen around the same time. Who, you might ask, is Sanford Allen?

Well, in 1961, this young man sat on the stage of Carnegie Hall as not only the first black member of the New York Philharmonic in the orchestra’s history, but as the first full-time African-American member of a major American orchestra. One might wonder what people thought he was capable of as he was growing up? And I wonder why no one told me about Sanford or his accomplishments, or the fact that he entered the Juilliard School at the age of ten, or that he premiered Sir Roland Hanna’s Sonata for Violin and Piano at the Kennedy Center or premiered Blue’s Forms, a piece written for him by Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson, a leading African-American composer. Why had no one told me or seemed to take note of these remarkable differences between what someone had become and what had been expected they would be capable of?

When I was 10 years old, my family moved from Manhattan to Hershey PA – a drastic social change for me, transitioning from the center of the world’s great metropolis to a town that had at the time (despite the constant smell of chocolate in the air) only one chocolate-colored family in my school. I wrote a poem about the experience and entitled it Moving.

Cement courtyards

giving way to landscaped lawns.

From the streets where

everyone’s a stranger,

To pleasantries provided

on every block.

Bustle and rush

slowing into serenity,

Five dollar movies

down to two-fifty.

Fair-weather friends replace

life-long companions,

Public school grounds

becoming selective suburban campus.

Blackness not uncommon

to uncommon being black,

Homeroom filled with fifty

slimmed to barely twenty-five.

Crustacean in an ocean

evolved to sea bass in a bowl of goldfish,

Comfortable happiness,

haphazardly disintegrating.

Trepidation, random rebellion,

ostracization succeeding,

Mosaic Manhattan extermination;

procreation Hershey.

After beginning my studies with Graffman at the 92nd Street Y in New York, I continued developing on the instrument through lessons at the Peabody Preparatory Music Institute in Baltimore, and served as Concertmaster of the Harrisburg Youth Symphony. I then spent my junior and senior years of high school at the Interlochen Arts Academy in Michigan. After Interlochen, I began my tenure as a college student at Penn State, where I was Concertmaster of the Penn State Philharmonic, and then went on to complete my Bachelors and Masters in Music at the University of Michigan. In all of those musical environments, I was either the only or one of less than a handful of minorities.

Interestingly enough, it was not until I was working on my degrees at the University of Michigan that I first learned there were any black composers. I literally went into a lesson one day and my teacher said, “Do you have any interest in playing music by black composers?” I looked at him kind of startled and said, “You mean black classical composers?” He smiled and began to pull volumes of works off his shelves. This then led to the incredible expansion of music I performed as I focused on the works of black and Latino composers for my undergraduate and graduate recitals.

And it led me again to question why no one had told me of William Grant Still, Coleridge Taylor-Perkinson, David Baker, Joseph Boulogne St. George (an Afro-French contemporary of Mozart’s), or the countless other minority composers whose accomplishments litter the annals of the classical music repertory. Why had no told me about George Polgreen Bridgetower, a well-known black violin virtuoso who was good friends with Beethoven and who premiered Beethoven’s famous Kreutzer Sonata with him in 1803 in Vienna. Beethoven wrote the work for him, which is why you see, in Beethoven’s original manuscript, the inscription, “Sonata mulattica composta per il mulatto.”

Why had no one told me that the great Frederick Douglass played the violin or that his grandson, Joseph Douglass, was the first black violinist to tour the United States as a recitalist in the early 1900s? And so, it was within the context of these questions and my immersion in the incredible music that I had recently been exposed to, combined with the lack of any minorities to be seen in the audiences or on stage at classical music concerts, that I was led to found the Sphinx Organization.

It was also at this time that I began to reflect on all the feedback that I received as I was growing up from peers and adults. And their comments were often not supportive of understanding the role of minorities in classical music. On the contrary, they sought to distance me from my racial heritage, and this led to my authoring the title poem of my book of poetry They Said I Wasn’t Really Black.

Born from white and brown young skins,

I was so diff’rent from the pack.

Adopted by Caucasians at just 2 weeks of age,

They couldn’t of known about the other people;

They said I wasn’t really Black.

A violinist I was destined for,

Early on I showed them the knack.

It was Mozart for me and Beethoven too,

I never got to memorize Jackson 5 lyrics so;

They said I wasn’t really Black.

School bells and cafeteria food,

I sat there with my brown lunch sack.

There was no fried chicken in my zip-lock bag,

No confrontation between watermelon and black-eyed peas;

They said I wasn’t really Black.

I’d stroll into the rehearsal room

Wishing I was the Daddy-Mack.

I didn’t even go to the games, let alone sport the jersey,

Hell, I wasn’t even in the band and I wonder why;

They said I wasn’t really Black.

I didn’t talk the talk and couldn’t walk the walk,

Familial prec’dent I did lack.

At first it seemed correct by design,

It took me years ‘til I was uncomfortable when;

They said I wasn’t really Black.

There were those who made me feel different,

And few who I thought had my back.

I could have taken all the racial slurs

If only it wasn’t my friends around when;

They said I wasn’t really Black.

All I sought was acceptance,

Any clique’s shell I could not crack.

They feared the anomaly, too bad for me,

That I got good grades, couldn’t play spades ‘cause;

They said I wasn’t really Black.

Then it settled down on me,

Weighting unease upon my back.

Like the line and rhyme of these words I write,

I had only just begun to fight when;

They said I wasn’t really Black.

The first African Queen I was to know

Drew me in like the sweet lilac.

She shut those doors, supposedly wanted more,

But I knew the reason behind because;

They said I wasn’t really Black.

For a time I had an Afro,

It should have got me on the track.

Foolish me, to think they’d see, what I wanted to be. Why did they all have to agree?

My skin was just a racial gi. Hopelessly, eventually;

They said I wasn’t really Black.

I’m glad I found out that they were wrong,

I ain’t born in Uncle Tom’s shack!

I guess they wish that color was not what it is,

But what they wanted it to be when;

They said I wasn’t really Black.

I have come to terms with what I cannot fight

I yearn no longer to attack.

The title I sought without emerged from within.

There was serenity in complacency when imperious to chagrin while;

They said I wasn’t really Black.

Every moment I burst with pride,

I toss a memory in my sack.

Their jibes ebb like the tide, as I open the flood-gates wide, It was quite a ride,

Over now save the rare aside, I wish I wouldn’t have cried, I kinda hope they lied when;

They said I wasn’t really Black.

One of the key things I want to provide you with is a brief overview of the Sphinx Organization and our various programs. However, I also want to share with you some background as to why the work we do is so critically important, and what the issues are of overcoming the challenges of increasing diversity in the arts. We must have some context in which to present these ideas – a context of where we are at now, and what is the distance we must travel to achieve “success.” Can we even define what success might looks like?

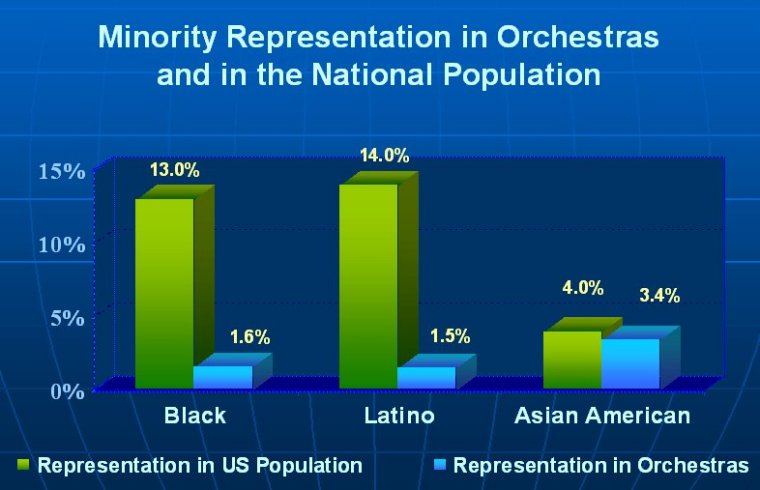

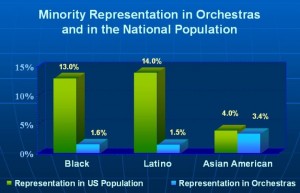

First, one of the best gauges is to look at American orchestras in terms of the percentage of minorities and when we do, we find that orchestras are 93% white, 1.6% black, and 1.5% Latino, with the remaining 3.5% primarily representing Asian-Americans. Anecdotally those statistics mean that when 3 ½ years ago the Chicago Symphony hired Tage Larsen, a black trumpeter, he was the first African- American ever in the history of the Chicago Symphony. The NY Philharmonic, back in the 1960s, hired Sanford Allen. Today there is still only one full-time African-American member of the NY Philharmonic.

It’s important to look at these statistics in terms of their representation in the overall population. Our goal is not to be the affirmative action entity within classical music; rather our goal is to achieve diversity within the field of classical music. Our goal is not segmented to a particular cultural or racial group, but rather to identify what groups are under-represented. We see the dramatic under-representation of blacks and Latinos in orchestras (1.5%) versus their representation in the overall population, at 13-14%. Sometimes I am asked, why not also focus on Asian-Americans? Because in classical music there is not the same under-representation for Asian-Americans, especially in orchestras, as they are 4% of the population yet make up 3.4% of orchestras.

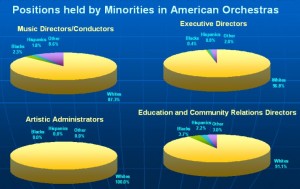

You see on stage that there is very little diversity. But the problem is much deeper than that. So it’s important to look at orchestras as an entire entity. What is it about their music directors, conductors, and staff that impacts their connection on communities? We find that almost 90% of music directors/conductors are white, with 2.3% black, 1.8% Latino, and 8.6% other. With executive directors – the key leadership position of an orchestra – we find that less than ½ of 1 percent (0.4%) are black and only 0.8% are Latino, with 2% other. And with artistic administrators, the key artistic leadership position in an orchestra, we find that there are no blacks and Latinos – statistically 0%. Even if we look at the education and community relations directors, where many orchestras will place a minority on their staff, we find that only 3.7% are black, 2.2% are Latino, with 3% other. These statistics give you a sense of the lack of diversity in our orchestras.

Programming – what are orchestras performing? If we look at the overall top ten composers performed by orchestras, we find that 0% are minority. Now that is not a big surprise, as there are a lot of European composers in that category. But even if we pull out the top ten most frequently-performed North American composers, still it’s 0% minority. What if we had a magical milestone, where our goal is to have just 1% of the music being performed by American orchestras be that of minorities? Unfortunately we’re not even close to a milestone such as that.

Now let’s consider what’s coming down the pike. If we look at the overall student body in music schools, we find that blacks represent 6.6% and Latinos 4.9%, with Asians at 4.8%. There is some sense that things are growing. However, when we compare all degrees, we find that the 6½ % of black bachelors’ level students drops to less than half of that, at 2.5%, at the doctoral level, Latinos remain about the same at 5.3%, but Asians make up 17.4% of doctoral candidates, a significant increase. Again, there is a dramatic under-representation of blacks and Latinos in music schools compared with their representation in the overall population. But when it comes to Asian-Americans, they are dramatically over- represented in doctoral programs (17.4%) compared to their percentage in the population (4.0%). It’s important for us at Sphinx to quantify this, so that we know where we are and we know what impact we are having.

Music school faculty is another key area to look at; here we see that whites make up about 90% of the total faculty, with 4.8% black, 2.7% Latino, and 3% other, but when we look at full professors, blacks are down to 3.5% and Latinos down to 1.9%.

Finally let’s look at youth orchestras, because this gives us a sense of even before college, where are we looking in terms of our young people. And unfortunately we see very, very similar statistics to music schools, with whites making up 75% of youth orchestras, blacks at 3.5%, Latinos at 4%, with 17.5% other, mostly Asian-Americans.

So now, with this understanding of the current environment of classical music, I hope you have an appropriate context in which to understand the necessity for the Sphinx Organization. The Sphinx Organization’s website http://www.sphinxmusic.org/ has a short video that presents the highlights of our work and accomplishments.

When you see Sanford Allen in that video, whether he was playing as Concertmaster of the Sphinx Symphony or sitting as a juror or giving a master class, I hope you can see that the impact he has on our young Laureates is literally immeasurable. I sit and I think about what his words mean to them as they build the skill sets and life experiences that will determine what the difference will be between what they are capable of becoming and what they will in fact become. What is the standard that has now been set out before them? Is it different than what I was taught or was exposed to when I was their age? Have we at Sphinx been able to build a platform upon which these young people can build successful careers?

One of the key events we hold each year, to celebrate the talents of our young artists, is our Sphinx Concert at Carnegie Hall presented by JPMorganChase. This unique concert, which sold out last year, takes place this year on Tuesday, September 25th and features the Sphinx Chamber Orchestra, the Harlem Quartet, and other top Sphinx soloists. The Harlem Quartet is a Sphinx ensemble where every member is a past First-Place Laureate of the Sphinx Competition. In addition to conducting residencies around the country, they serve as Visiting Faculty at our Preparatory Music Institute and Senior Faculty at the Sphinx Performance Academy.

The Sphinx Chamber Orchestra is comprised solely of Sphinx alumni and has received rave reviews for their past performances, with the New York Times stating that they were, “more beautiful, precise and carefully shaped than fully-professional orchestras that come through Carnegie Hall, first-rate in every way.”

My mother was the reason for my starting and loving the violin. Everyday through our various programs at Sphinx, I try to recreate for our young people at least a part of the inspiration that she gave me. As I conclude, I would ask each and every one of you to contemplate this issue of diversity in and access to the arts, and consider not if but how you will act to play some role in impacting what is truly one of the last fields left in our country lacking the representation of our citizenry as a whole.

Martin Luther King said it best when he said,

Change does not roll in on the wheels of inevitability, but comes through continuous struggle. History will have to record that the greatest tragedy of this period was not the strident clamor of the bad people, but the appalling silence of the good people. Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.

And I submit to you, this work we do matters! If you are a teacher or arts educator, ensure that your students and curriculum reflect the whole community in which you live and work. If you are a student, learn not just the works of the traditional repertoire but seek out the incredible contributions of minority composers who have not received the same level of exposure, yet nonetheless represent the greatest our art form has to offer. If you are an arts leader, do not rest until your respective institutions have developed and implemented strategies and policies that embrace the diversity in our field. If you represent a corporation or foundation or have individual resources that can be brought to bear to create the sustainable evolution that our field needs to truly impact not just the lives of young people but of our entire society, then do not hesitate to join Sphinx and the other organizations that are making a difference today to change our tomorrow!

I began our time together by sharing part of my personal story with you and, as you think about Sanford Allen, the many composers and performers I have mentioned, and our professional Sphinx musicians and young talented students, I hope I am leaving you with a renewed sense of Ashley Montagu’s words,

The deepest defeat suffered by human beings is constituted by the difference between what one was capable of becoming and what one has in fact become.

Your potential role in affecting that difference in another may have quite an impact on how you determine what you have become.

[…] a focus on inclusion.” (For a fascinating look at Aaron Dworkin’s background, read a lecture he gave at the Chautauqua Institute a few years […]