Issue No. 16: October, 2003

Publisher’s Notes by Frederick Zenone

A Bold Experiment by Bruce Coppock

Good Governance for Challenging Times: The SPCO Experience by Lowell J. Noteboom

Contract Renewal Process: Through Musicians’ Lenses

A Bold Experiment: The Processby Paul Boulian

An Orchestra Outside of the Box by Marianne C. Lockwood

About the Cover by Phillip Huscher

Toward Meaningful Change by Catherine Maciariello

Confluence: Leadership, Collegiality, Good Fortune by Marilyn D. Scholl

The Elgin Symphony Orchestra: Growth with a Plan

Orchestra and Community: Another Look by Markand Thakar

Walking in Two Worlds: A Librarian’s Perspective by Karen Schnackenberg

From Challenge to Success: What Must Change? by Gideon Toeplitz

Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra Strategic Plan

Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra 2010 Vision Statement

Publisher’s Notes

While we read almost daily about the financial challenges that American orchestras are facing, we rarely read in the popular press about a range of challenges that some orchestras are facing in collaborative and imaginative ways. In this issue of Harmony, in addition to reporting about the dramatic progress that one orchestra has made in addressing its financial crisis, we direct your attention to other orchestras engaged in addressing the challenges of changing roles, shared responsibilities, inclusive governance, bold vision, and collaborative planning. In the long term, it is likely that the core work of boards will still be governance, staff members will still manage, and musicians will still make music. But there is a new dialogue about the limitations of rigid boundaries for those roles and responsibilities.

In 2002, the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra (SPCO) completed an 18-month strategic-planning exercise that included representatives from all orchestra constituencies. Through that exercise, the organization had decided who and what it wanted to become. It now faced the question of how to get there. During the course of their strategic-planning work, members of the organization had developed a taste for rigorous cross-constituency deliberation. The SPCO invited the Symphony Orchestra Institute to help its constituencies develop a deliberative process that would take the strategic plan from words on paper to actions, while at the same time undertaking a renewal of the collective bargaining agreement between the SPCO and its musicians.

To undertake such an examination as an organization is challenging; to do so while intending to arrive at a contract renewal is an unusually bold step because it requires careful reexamination of positions and practices that have been in place for a long time. Those who participated in the SPCO’s contract renewal process became introspective in deeply deliberative, collaborative, and inclusive ways. Much of what the Contract Renewal Group addressed in Saint Paul has rarely been addressed within American symphony organizations, and if it has been addressed, the work has been done on a much smaller, single-constituency level in which it could be assumed that people were of like opinion.

In this issue of Harmony, there are four articles prepared by some of the leaders of this journey. Bruce Coppock and Lowell Noteboom have written from their respective positions as president and board chair of the SPCO. The five musicians, Kyu-Young Kim, Tom Kornacker, Sarah Lewis, Charles Ullery, and Herb Winslow, who served as members of the Contract Renewal Group, share their thoughts through an Institute roundtable. And Paul Boulian describes the process that the participants used to acknowledge their shared values and to move in the direction of making decisions as one constituency without feeling threats to their individual identities.

Trust and its care and feeding are central to the success of this kind of journey. So, too, is a belief that tension and disagreement are not necessarily destructive. Both conditions existed in Saint Paul. The SPCO’s bold experiment produced a plan unlike any other we know in American orchestras. We hope it will provoke serious thinking about our orchestra world. It is bound to produce vigorous conversation.

The Orchestra of St. Luke’s represents a different model of how an organization began and how it grew. As Marianne Lockwood, St. Luke’s president and executive director, explains, it began as a chamber music organization and only later became an orchestra. Along the way, the organization took with it the values of inclusiveness, collaboration, and shared goals that are common practice in the world of chamber music. As audience members, we know what those values produce in chamber-music performance. The Orchestra of St. Luke’s gives us a glimpse at what those values produced at an organizational level.

It is notable that as is preferred by the musicians, St. Luke’s remains a per-service orchestra. Working from a core of players, the organization adds and subtracts personnel from a select cadre of musicians on an as-needed basis, depending on the repertoire. It’s a practice reminiscent of the larger- scale London Symphony Orchestra in its earlier days as was described in Harmony #13. This structure has also been the practice of orchestras in many smaller U.S. cities. The Orchestra of St. Luke’s is a flourishing example of this model.

For the past three and one-half years, 15 American orchestras have participated in an initiative funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The effort is intended to bring meaningful change to the orchestra industry by sharing what is learned in the 15 orchestra “laboratories.” Catherine Maciariello is the foundation’s program officer for the initiative. This past June, she addressed many in attendance at the American Symphony Orchestra League’s conference in San Francisco. We are pleased to share with Harmony readers her remarks about the genesis, results to date, and future challenges of this program.

The Saint Louis Symphony could be the “canary in the mine” metaphor for many of us. And in this case, the canary has returned to the surface to sing. This orchestra has been ambitious in striving toward excellence and ambitious to present its excellence widely. The organization created practices and programs that were imitated models, but ultimately found its high ideals and broad ambitions truly beyond its financial grasp. The crisis was sobering. Harmony editor Marilyn Scholl chronicles the organization’s journey from near catastrophe toward stabilization and a bright future. It is a story of leadership, sacrifice, difficult choices, and the awakening of community conscience, all directed at saving a great community resource.

The suburbs of many American cities are homes to dozens of smaller- budget orchestras playing the classical repertoire regularly. Elgin, Illinois is one of those suburbs. The Elgin Symphony Orchestra came to the Institute’s attention by virtue of the rapid growth of its budget. When we began to inquire, we learned that the organization attributes its success to a rigorous, collaborative, annual strategic-planning process—a process that includes representatives of all constituencies—that focuses on matching a goal of ever- stronger artistic product with financial reality. We thank Doris Gallant, Michael Pastreich, Emanuel Semerad, Tim Shaffer, and John Totten for participating in an Institute roundtable to take readers inside the organization’s planning process.

In Harmony #15, we published a speech that Penelope McPhee, vice president and chief program officer of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, had delivered to a gathering of participants in the foundation’s “Magic of Music” initiative. We invited reader response to “Orchestra and Community: Bridging the Gap.” Markand Thakar accepted our invitation and offers his views as to why orchestras are reluctant to make the changes for which the Knight Foundation calls. Thakar brings to his essay his dual perspectives as music director of the Duluth Superior Symphony Orchestra in Minnesota and co- director of the graduate conducting program at Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore. We thank him for taking keyboard in hand to remind us of the value of differing opinions.

We also thank Karen Schnackenberg, chief orchestra librarian of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra and a member of the Institute’s Board of Advisors, for reminding us that not all collaborative, cross-constituency undertakings need be vast of scale. Karen is a strong proponent of the notion that orchestra librarians are both musicians and administrators, and that thought comes through clearly in her essay to describe two successful initiatives in her orchestra.

In this issue’s final essay, Gideon Toeplitz challenges readers to consider seriously what must change if American symphony orchestras are to survive and thrive. Gideon is a 30-year veteran of orchestra management and many of these thoughts have been on his mind for a long time. It was Gideon who oversaw the introduction of Hoshin to the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra (as reported in Harmony #7) and his passion for the music, as well as his determination that American orchestras work smarter, resounds in his essay.

For nine years, the Symphony Orchestra Institute has published Harmony as a periodical. This 16th issue is our largest. Harmony has become the central forum for information and discussion about better-functioning symphony organizations

However, we at the Institute have come to a time when we must ask difficult questions and make difficult decisions about how to use our resources. As you will note in the statement that follows, we are no longer able to meet the human and financial demands of periodical publishing. We do intend to pursue activities that will merit publication from time to time, whether in print or on the web.

This year, for instance, we have worked with the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra, and the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra. The work with the SPCO is reported in depth in this issue. We think it is some of the most important field work we have done. The Institute will continue to undertake different kinds of fields projects where it is felt we can be effective.

We are proud of the 16 issues of Harmony that are now archived, with search capabilities, on our website. Our newly expanded bibliography, also available on the website, is a vital resource for information about symphony organizations and their development. It will be useful for many years ahead.

This final issue of Harmony and the prior 15 issues were produced only with the time, dedication, and hard work of many. Those who have written for the journal have been reflective, informative, and often provocative while always pointing us toward positive change. We want to acknowledge the passion and expertise of Harmony editor Marilyn Scholl and the dedication of David Scholl and Katie Byrne for their work with publication, distribution, the website, and communications. Many thanks also to Phillip Huscher whose erudition and cover choices have 16 times reminded us and our readers that this is indeed a great art we serve.

To Our Readers

This 16th issue will be the final publication of Harmony by the Institute, in its present form and on a regular, periodic basis. The Institute has concluded that the content-development process, management and operational requirements, and expense of publishing Harmony on a regular, periodic basis are now beyond its human and financial resources.

We will maintain our website, <www.soi.org>, and an archive of prior Harmony content, including that of this final periodic issue, will be posted there.

Looking to the future, we plan to continue to post on the website reports, articles, dialogue, and other content—in downloadable and printable form— which we believe address, describe, and foster, in especially pertinent ways, transformational change within symphony orchestra organizations and the industry as a whole. We may from time to time publish, print, and distribute such material under the Harmony name, whenever that communication avenue will be especially effective.

The Institute will also continue to foster and pursue various forms of consultation and facilitation efforts in the field, to nurture positive changes within symphony organizations and the industry as a whole, toward the preservation and enhancement of symphony orchestra organizations and the essential musical and cultural services and value they provide their communities.

Editor’s Thanks

The Institute’s decision to discontinue publication of Harmony as a periodical is, as you can imagine, a cause for sadness on the part of this editor. But having edited all 16 issues, I also find it an occasion on which to offer my deepest thanks. To the 61 authors, dozens of roundtable participants and interviewees, writers of letters to the editor, and countless supporters of this publication, kudos! Your can-do spirit and willingness to share your work and your thinking in these pages has energized and emboldened an entire field.

I am in particular debt to Phillip Huscher who has 16 times carried forth our idea of gracing the cover of Harmony with a classical score fragment and dared you to guess what and why. Also to Beth Judy for her black- and blue- pencil proofreading of thousands of pages. And to my business partner (and spouse) David Scholl who has completed every inch of typesetting and every detail of design and production for these 16 issues. My final thanks go to Katie Byrne, our communication specialist, who has demonstrated amazing agility in knowing who you, our readers, are and where you are. You are a decidedly mobile group of more than 6,500.

Nine years ago, Marilyn Scholl was a 25-year subscriber to the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, a woman who knew and loved the music, but one who had little knowledge of orchestras as organizations. In the intervening years, you have welcomed me into your concert halls and into your conversations. My life has been enriched. For that opportunity, heartfelt thanks.

The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra

Beginning in 2002 and continuing into 2003, representatives of the Symphony Orchestra Institute worked with members of the Saint Paul

Chamber Orchestra (SPCO) family as that organization undertook a journey to take a strategic plan from words to actions and simultaneously to complete a musicians’ contract renewal. Paul Boulian and Fred Zenone designed and led the process from beginning to end. In the special section that follows, we present four views of that work.

The section opens with a sustained essay written by SPCO president Bruce Coppock, who sets the stage for the work and explains the content of the many sessions in which participants engaged. Coppock also shares the consequences of nasty financial surprises, as well as those of an extraordinary opportunity that presented itself at an awkward moment. He concludes with a compendium of the success of the organization’s “Bold Experiment.”

SPCO board chair Lowell Noteboom shares his thoughts about “Good Governance for Challenging Times.” He suggests what governance is and what it is not, and reviews pertinent literature to demonstrate how thoughts about nonprofit governance have changed over time. He then takes us step-by-step through the development of the organization’s strategic plan and contract renewal. He concludes with thoughts about the dramatically changed ways in which the organization will do business as musicians assume new levels of involvement in all aspects of the SPCO’s work.

The five musicians who served as members of the Contract Renewal Group share their thoughts about the collaborative process via an Institute roundtable. They tell us about their experiences as participants and explore how their lives as musicians will change as a result of the terms of their new contract. They conclude with thoughts for other orchestras to consider.

The final entry in this section is written by the “design guy,” Paul Boulian. Long-time readers of Harmony are familiar with Boulian’s work with the Hartford Symphony Orchestra (as reported in Harmony #5) and with the Philadelphia Orchestra (as reported in Harmony #14). Here he explains in detail how the work in Saint Paul began, how it evolved, and how it was completed.

Our Saint Paul authors present challenging material that requires thoughtful reading and reflection. We extend our thanks to them for expending the extraordinary amounts of time it took to prepare this material to share with the field.

A Bold Experiment

During the 10 months between August 2002 and May 2003, the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra (SPCO) undertook a bold experiment in contract negotiations. By design, and without predisposition as to the result, eleven members of the SPCO organization—five musicians, three senior staff members including myself, and three board members—embarked on a process to produce a collective bargaining agreement for the SPCO using a new approach, having agreed in advance that we did not wish to negotiate in the traditional way, and recognizing our fairly well-developed ability to “get along” and work well together. The SPCO environment has traditionally been warm, cordial, and polite, Minnesotan for sure, but also cohesive enough that we did not require “remedial” work in labor-board- management relations. We all were motivated by the desire to do it better than we had before, while admittedly not quite sure what better might look like.

After the orchestra and staff had agreed in the spring of 2002 that we would seek an alternative approach to our negotiations, we discussed a number of possibilities. We had recently completed a strategic-planning process that involved approximately equal numbers of musicians, staff, and board members. Demystifying the board—and its attitudes and motivations—had been very helpful during our planning. Orchestra members and staff suggested imitating that format for negotiations, and the board leadership concurred and agreed to participate. After considerable discussion, we agreed to engage Fred Zenone and Paul Boulian to lead a renewal dialogue. The SPCO’s recent background of comparative financial stability, artistic excellence, cordial organizational dynamics, and focused strategic planning all contributed to Fred and Paul’s interest in the SPCO project, as did the SPCO’s demonstrated energy to try a new approach.

The contract renewal process was by any measure extraordinary. It was an emotionally engaging, exhaustingly challenging roller coaster ride for all involved, including the orchestra with whose future we were struggling. Importantly, the process was not an outgrowth of an immediate financial crisis, although a serious financial situation did emerge and nearly upstage the contract renewal process midway. It was not a response to an artistic crisis or the departure of key personnel, although at some basic level, artistic issues turned out to be at the heart of our discussions. It was not a response to an institutional failure, such as a strike or a lockout, a decline in attendance, or bad press about artistic or organizational matters. Each of those nightmares—or worse—was, however, a possible outcome if we failed to address the SPCO’s challenges effectively.

Rather, the work of the Contract Renewal Group (CRG), and the results we produced, were our responses to something far less tangible: together we felt deep down that the SPCO simply must become better than it already is, artistically, organizationally, financially, and culturally. That was the very essence of our first stated value of excellence, as we had defined it for ourselves in our 2002 strategic plan: striving for peak performance individually and collectively throughout the organization. Not merely good performance, or even very good performance, or God forbid, good enough performance. Through our strategic planning process, the whole organization had committed itself to strive toward peak performance together collectively as an organization, and individually as players, managers, trustees, leaders, and colleagues.

Before we began this extraordinary journey in August 2002, even without the benefit of the rigorous analysis, introspection, and struggle that ensued, each of us in the Contract Renewal Group understood that grappling with the issue of excellence would demand an enormous effort from each of us. We did not yet understand what would be required of us collectively to function as an organization bound together by a deeper commitment to excellence, having intentionally and collectively made a commitment to individual and collective peak performance. That is why we sought Fred and Paul’s assistance to facilitate our discussions.

Wasn’t the SPCO just fine as it was? Hadn’t we balanced our budget for nine consecutive years, one of the longest such runs in the industry? Wasn’t the SPCO quite widely recognized as a first-rate chamber orchestra? Of course it was and is. But deep down, we all felt our organization had to be better. Success in meeting our aggressive goals would be the result of the SPCO stretching and reaching for them, not providence bestowing them upon us. We were reminded of the ancient Chinese proverb: “A peasant must stand a long time on a hillside with his mouth open before a roast duck flies in.”

At some level, to struggle openly with questions of our excellence seemed negative, self-defeating, and downright dangerous. However, three external forces, when combined with an overarching—and widely agreed upon—goal of becoming preeminent among the world’s chamber orchestras, forced us into this painful and exhilarating journey. It was a journey of reexamination of all of our organizational behaviors, our comparative standing, internal rituals and mythologies of the orchestra world, and the contract rules by which we live.

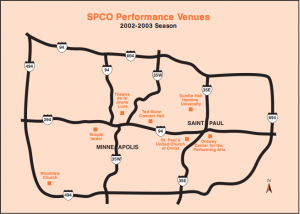

First, we operate in the most densely saturated orchestral market in the country. The Twin Cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul are the only metropolitan area in the U.S. with two first-rate orchestras offering full concert seasons. As a result, there are more orchestra tickets for sale on a per capita basis by a factor of two here than in any other market in the country (including New York, Boston, Los Angeles, and San Francisco). Unlike nearly every other major U.S. orchestra, the SPCO is not the only show in town. We not only compete directly for audience with another fine orchestra, but we also compete directly for funding, board members, and a place in the community psyche.

Second, during the past 30 years, there has been a worldwide explosion of chamber orchestras. Even more daunting for the SPCO, this proliferation has predominantly taken the form of specialty ensembles: original instrument Baroque orchestras; classical chamber orchestras; contemporary music ensembles. Check the roster of “SPCO competition” circa 1975: there wasn’t much. You won’t find many of the staples of today: the Chamber Orchestra of Europe, Ensemble Modern, Tafelmusik, Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, London Sinfonietta, the Orchestra of St. Luke’s, Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, and many others. In a suddenly crowded and very competitive field, the SPCO finds itself generalists in a world of specialists.

Third, geography and local culture. In addition to being Midwestern, generally a liability in our industry with its coastal biases, Minnesota is cold! Furthermore, Minnesota is the land where everyone is, as Garrison Keillor tells us, “above average,” which makes an overt effort toward artistic preeminence suspect.

We had gained some understanding of these dynamics during our strategic- planning process. For example, the only vote taken in 20 months of planning meetings was about whether our vision statement should articulate the future SPCO as “the” beacon of quality or “a” beacon of quality. The advocates of “the” prevailed by a single vote! Minnesotans are uncomfortable with the idea of openly trying to be the best at something; it seems snooty, and perhaps somewhat unnecessary. Indeed, some of our musicians and board members wondered aloud why the strategic plan so aggressively urged us forward to be the best; wasn’t “among the best” good enough? Wouldn’t we offend people by suggesting that we wanted to be seen as the preeminent chamber orchestra in the world? So how would that Minnesotan modesty—deeply embedded in the SPCO culture—position the SPCO to attract the most superior talent, talent worthy of the world’s preeminent chamber orchestra? After all, it takes a lot more than “very good” to attract superior artists from bucolic European homes and bustling major international cities. And where is our competition based? New York, Frankfurt, London, Paris, Berlin, Toronto, etc. The only factor we can employ to overcome geography and culture is superior performance. The artists we seek as regular members of the SPCO, and as conductors and collaborators, need a special reason to come to Minnesota: the excellence of the enterprise in all of its facets.

Fierce local competition, recently developed international competition, and the challenges of geography and culture. These were three important factors over which we had little or no control, but to which we had to find powerful responses.

Early Meetings: Feeling Our Way through Murky Stuff

Early discussions about our challenges quickly came down to understanding that overused word “excellence.” Excellence is something that we in the orchestra business tend to stipulate, even to the point of dismissiveness, perhaps because it makes everyone a little uncomfortable. Listen to orchestra managers talk: “Of course, the orchestra played excellently.” Listen to artist’s managers talk: “So and so was just fabulous . . . received a standing ovation and talk of re-engagement.” Listen to orchestra players talk: “Our orchestra can play anything fabulously . . . provided the right person is on the podium!” And listen to conductors talk: “The orchestra played fabulously for me.” And listen to what our institutions bombard our publics with: “world-class, superior, first-rate, without equal.” We act as if, with all the perils facing orchestras, the excellence of what we do should not and cannot be questioned. Is it just possible that our audiences, the very lifeblood of our organizations, are far more discriminating that we think? Even if they are unable to verbalize what was or was not compelling about a concert, at some visceral level, audience members will respond—by deciding to attend our concerts again, or by deciding to try something else. Given our highly competitive arenas, the CRG thought that examining our own behaviors around excellence was an important line of inquiry. As Tom Morris, executive director of the Cleveland Orchestra, who was a consultant to our strategic-planning process, had often reminded us, “Nothing succeeds like great concerts.” We began to allow ourselves to say out loud that maybe the SPCO was giving too many good concerts and not enough great ones.

We were struggling with very difficult issues and increasingly gaining the courage to face ourselves head on. While constantly reminding ourselves of our many successes over 44 years, we were beginning to coalesce around the idea that something wasn’t quite right at the SPCO—at its core. Maybe we ran the risk of talking the talk about the SPCO, but not walking the walk. Maybe we were indeed giving far too many good concerts and not enough great concerts; maybe we talked a lot about how, as a chamber orchestra, we are different, but we rarely acted really differently from a symphony orchestra; indeed, our collective bargaining agreement read essentially as that of any of the largest 25 symphony orchestras in America. Maybe we just weren’t as jazzed up about being the SPCO as we needed to be. In the Contract Renewal Group, we had to find a way to come to grips with all these ideas to make the pursuit of our vision of artistic preeminence a daily reality. The contract with our musicians—in the very broad sense that it defines the work to be done—had to be a central vehicle to focus our organization on addressing these tough issues.

In varying ways, each of us in the CRG struggled with these and many other issues, consciously and unconsciously, directly and indirectly during the first few meetings. As we readied ourselves to tackle each issue more specifically, none of us really knew where we would or should end up. As Fred and Paul guided us in feeling our way, we slowly became more open and candid with each other. A sense developed that there was a critical mass of readiness—some combination of dissatisfaction, a sense of adventure and purpose, and serious commitment to the betterment of the organization—that gave us the courage to explore ourselves in ways we never had before.

Where Did This Process Lead Us? What Did We Achieve?

Our process achieved a significant and early success in the form of a four- year collective bargaining agreement between the musicians of the SPCO and the Society, ratified by a narrow majority of musicians three months prior to the expiration of the prior agreement. By some measures of excellence, that constitutes success, but there is nothing novel or so special about that result, for it has been achieved many times before, here and elsewhere. Thus our success really resides neither in the contract’s ratification nor in its early completion. Rather, the success we wish to share really resides in the fundamentally different ways in which we agreed to address our many challenges. Furthermore, we ended up agreeing to very substantive changes to the scope and nature of SPCO musicians’ work, to our institution’s governance, and to organizational decision-making responsibility. We also agreed to a radical shift in the locus for artistic responsibility, and instituted a comprehensive process for feedback and professional growth for our musicians.

This new contract creates methodologies for realms of activity and organizational interaction unique in our industry. It is a bold and idealistic experiment, rooted in common values and common resolve. Its success, however dramatic, nonetheless still exists only in form: it codifies methodologies and systems for a strategic response to our circumstances as we understand them. It will be up to everyone in our organization to use these new methodologies to create more great concerts, and fewer good ones. As this article is published, we have taken some baby steps in the implementation of our new systems, and the initial results are quite positive, but it is still very early.

To suggest that progress was linear in arriving at this important base camp in our long, tall climb would be disingenuous. To suggest that critical mass sufficient to win ratification implies universal agreement would be downright dishonest. The very narrow ratification majority of the orchestra speaks to the challenges our new contract provides for all of us. There is no question that each of us in the CRG is passionately committed to this path. There is equally no question that our new agreement has angered some, threatened others, bewildered many, and exhilarated and inspired several, both within our orchestra and around the industry—musicians, managers, and trustees alike. The intensity of the responses to the new agreement tells us, at the very least, that something extraordinary did indeed take place in Saint Paul. Thus, we are keenly aware of the tenuousness of our “critical mass” and how vigorously we will need to strive to sustain this work. The initial vigor with which the many musicians of the orchestra have undertaken the new work of the SPCO is very gratifying, especially since several of the musicians now most involved were as skeptical of the CRG’s approach as they were of its results.

The Process

The process we used was devised largely by Paul Boulian and Fred Zenone, with substantive input from Herb Winslow, Lowell Noteboom, and me, in our respective roles of negotiating committee chair, board chair, and SPCO president. The CRG also participated in formulating work plans for each meeting. The process is described in detail in Paul Boulian’s companion article in this edition of Harmony. It therefore does not merit much further comment here, except to underscore the importance of process to the results we achieved. Some in the orchestra industry have dismissed our success as merely a process, signifying nothing. Others have dismissed our success as a function of the SPCO being merely a chamber orchestra. These are both erroneous suggestions. Those of us involved directly in this saga would agree that several other factors—the readiness factors—played far greater roles in making the process a successful vehicle for substantive changes to our organization.

The Readiness Factors

Five factors played vital roles in setting the stage for our agreement, and helped to create the right environment for success. Readiness factors were essential underpinnings, like a solid foundation for a house, without which we almost certainly would have failed. They are emphasized here largely to underscore their importance. Three years of readiness work preceded the contract renewal process.

Common vision. Through the highly inclusive strategic-planning process that preceded these discussions, which in its own right lasted 20 months from September 2000 through May 2002, we had together gained a common under- standing of our envisioned future. Using our own adaptation of Jim Collins’s conceptual template for institutional vision (outlined so compellingly in his book, Built to Last, co-authored with Jerry Porras), and most ably assisted by two consultants, Tom Morris and Ronnie Brooks (director of the Institute for Renewing Community Leadership in Saint Paul), we developed a clear and ambitious vision for the SPCO. Over those 20 months, this vision’s core val- ues, BHAGs (big, hairy, audacious goals), and descriptions of our envisioned future began to penetrate our organizational language forcefully enough to provide real context and framework for daily decisions. (A copy of the full plan, including the one-page vision statement, is available at <www.soi.org/ reading/index.shtml>.)

Committed, courageous leaders. To share our story accurately requires acknowledgement of the courage of the musicians and the commitment of the board and staff members who participated in the contract renewal process.

Herb Winslow and Tom Kornacker, negotiating committee chair and orchestra committee chair respectively, provided outstanding leadership to their colleagues and to the institution. Along with their three other orchestra colleagues on the CRG (bassoonist Chuck Ullery, violinist Kyu-Young Kim, and cellist Sarah Lewis), and ultimately with many other members of the SPCO, they deserve the highest praise for the quality and courage of their efforts. They engaged themselves intellectually in the artistic and strategic challenges, they listened carefully and thoroughly to the many voices from the orchestra, and they opened themselves up to highly threatening concepts. Throughout the process, these five musicians demonstrated integrated thinking skills of exceptional levels. Herb was extraordinarily adept in leading several full meetings of the orchestra.

We were the beneficiaries of equally committed leadership from three trustees, led by Lowell Noteboom, our board chair and president of the Minneapolis law firm, Leonard, Street & Deinard. He was joined in this effort by board members Don Birdsong and Sallie Lilenthal. It is one thing for management (whose job it is) and musicians (whose future it is) to devote 40 extra full days to such an enterprise. It is altogether something else for busy volunteers to demonstrate this level of commitment. The tenacity, intellectual capacity, and strategic acuity of our board members were important factors in…

THE SPCO’S PURPOSE

VISION STATEMENT

Providing innovative discovery and distinctive experience through the brilliant performance and vigorous advocacy of the chamber orchestra and chamber music repertoire.

THE SPCO’S CORE VALUES

Excellence: Striving for peak performance individually and collectively throughout the organization.

Intimacy: Striving to create powerful, deep connections between and among performers and audiences through music; fostering close collaboration and respect among all internal constituencies.

Innovation: Aspiring toward versatility and the ability to invent and do whatever is needed; being willing to risk failure.

Continuity: Aspiring intentionally to stay the course in pursuit of long-term goals.

BHAGs: BIG, HAIRY, AUDACIOUS GOALS FOR THE NEXT 10 TO 30 YEARS

To be widely recognized as “America’s Chamber Orchestra”

• Sold-out series in key American cities of artistic significance

• Unavoidable presence at major world festivals and concert halls

• Regular high-profile European touring

•Unanimous national and international critical acclaim

• The international organization of choice for special artistic projects

To be clearly distinctive in purpose and artistic profile

• Clear and focused profile as a chamber orchestra, not a symphony orchestra; three discrete repertoires (Baroque, Classical Viennese, Music of Our Time) with distinctive performance styles

• Serving the community and music in myriad ways: education, community service, collaborations, technology; extensive community engagement, out reach and education

• Innovative labor relations, and willingness to do business together in non- traditional ways

• Strong centers of concert and program activity in both Saint Paul and Minneapolis

To be the symbol of cultural excellence in the Twin Cities

• Enthusiastic, trusting and overflowing audiences • The symbol of excellence in the community • Center of the community’s broader psyche • The SPCO Board is the board of choice

• Endowment to operating costs in ratio of at least six to one • Robust financial foundation of annual revenues that support artistic initiatives, both local and international • Own or control a distinctive, innovative and acoustically superior facility (or facilities) that supports the SPCO’s unique repertoire profile and acts as a magnet for superlative musicians, composers and conductors, administrators, board members and audiences.

…our success. Their involvement in what was at its core a contract negotiation broke one of the cardinal industry rules: never let the board members into the negotiating room. Contrary to conventional wisdom, their presence contributed mightily to the outcomes we achieved.

Those of us on the staff who participated deserve credit as well, particularly my colleagues Barry Kempton (vice president and general manger) and Beth Villaume (vice president for finance and administration). Each brought to this process fervor, passionate belief in the vision, a willingness to sacrifice many sacred cows, and tenacious attention to “homework assignments” throughout.

There is a compelling thought in Jim Collins’s second book, From Good to Great, in which he debunks the notion that people are a company’s greatest asset. Rather, he asserts, having the right people “on the bus” is one of several essential factors in getting from good to great. Further, he suggests, companies that made the leap did so by getting the right people together first, and then letting them figure out the strategies that would provide for growth and improvement, rather than the other way around. We had the right people on our bus.

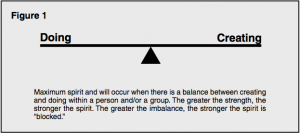

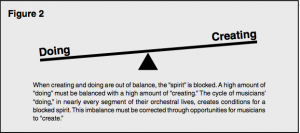

A common desire for change. Although we may have initially sensed things differently, we all seemed to grasp the notion—intuitively at first and more and more empirically as the process developed—that something was not quite right at the core of the SPCO. That core, it turned out, was hit upon in a burst of understanding—a true “aha” moment—about a month into our work. In the middle of a particularly angst-filled session about attitudes and frustrations, Paul Boulian leapt up and drew the following chart.

In seeing that chart, we all realized that it was the musical and emotional spirit of SPCO musicians that was blocked—the very people most critical to the SPCO’s ultimate success. Our united task became to define how to unlock that spirit again. However hokey, or perhaps embarrassing that may sound to some, we knew, in one of those seminal moments, that in acknowledging our broken spirit, we had faced the bitter truth head on—yet another of Jim Collins’s axiomatic factors in moving from good to great. A dispirited orchestra was not an orchestra that would make the leap we described in our plan. We were motivated to find the best ways to unleash the orchestra’s spirit anew. We were further motivated by the belief that taking the easy way out and doing nothing major to the contract was a far scarier proposition than whatever new path we might develop. We would have to make big changes to overcome the malaise of blocked spirit. The diagram in Figure 2 showed us the cycle we needed to break.

Frustration with traditional bargaining. At the end of the 2001 negotiations, musicians (and their lawyer) and management (and its lawyer) were agreed that the traditional approach used had resulted in nothing better than a stalemate. That approach produced tension, secrecy, and suspicion on both sides. Even more importantly, it had failed to advance the strategic needs of the SPCO. Even though an agreement was ratified early, and was rarely contentious, its traditional mindsets and framework produced traditional results. That frustration had fueled our common aspiration to approach 2003 differently.

Safety, candor, and willingness to live by the ground rules.Many of the members of the CRG had participated actively in the strategic-planning process during 2000, 2001, and 2002. We had come to know each other pretty well. In fact, we had become accustomed to the idea that our culture was a cooperative one, especially by American orchestra-industry standards. Our old Minnesotan notion of “above average” might have misled us into the idea that there wasn’t room for big improvement. Here, Fred Zenone and Paul Boulian brought rigor, standards, and methodologies that helped us to develop safer, deeper, and more candid conversations. Over the course of the process, our group basically clicked: we like each other, we respect each other, we appreciate each other’s limits and strengths, and we manage to tolerate each other’s idiosyncratic obsessions. Further, we followed rules of engagement that we developed together with Fred and Paul’s assistance. They were vital in developing the right atmosphere for our work. Paul discusses these principles in his article beginning on page 57.

The Discovery Phase

The first eight or ten meetings following our organizational ones were spent in discovery. How did we believe we really stood in relation to achieving our BHAGs? How well did we really live our four values? Who is our national and international competition? How do they operate? Who plays in those chamber orchestras? Who is our local competition? How do we stack up against them? What competitive advantages do they have? What competitive advantages do we have? Through the varying lenses of musicians, board members, and staff, what is the SPCO’s relative competitive position, and what critical success factors could we identify?

To discover what we thought of ourselves, each member of the CRG answered the question, “How close is the SPCO to achieving its big, hairy, audacious goals?” by rating each of our three BHAGs on a scale of one to six, with one representing “very far away” and six representing “very close/almost there.” However subjective and flawed the methodology might be, our poll told us something of crucial importance: a cross-section of the SPCO leadership—musicians, board members, and staff—believed we were somewhere between 30 and 40 percent of the way toward achieving our goals. We had a long way to go.

We then turned our attention to our stated core values by addressing the question: “How well-imbued into the fabric of the SPCO are its identified values (excellence, intimacy, innovation, and continuity)?” Again using a scale of one to six, in which one represented “scarcely imbued” and six represented “very strongly imbued,” we determined that we were slightly more than 50 percent of the way toward developing a culture based on our values. We acknowledged the work to be done.

We moved on to a variety of questions, using similar methodologies, to rank ourselves vis-à-vis our many competitors. We ranked ourselves in the arenas of musician, board, and staff recruitment and retention; we ranked ourselves against national, international, and local competition. We ranked the SPCO on such quantifiable variables as annual salaries and such ephemeral ones as “organizational sizzle.” We used highly subjective evaluation methodologies, including three versions of the smiley face—from severe frowning to intense smiling—to create a visual scale of one to five. The SPCO received overall rankings ranging from slightly better than severe frowning to slightly better than a neutral face. In general, our competition fared better, in our estimation. The point is that we looked at ourselves and our competition very closely, and we emerged from the exercise convinced that our competition was real, was farther along toward our goals than we were, and that we had to do something about it.

Perhaps we were, as a group, too hard on ourselves, but the empirical evidence and our ready agreement on qualitative matters were both startling. We likely thought more highly of our various competitors than they perhaps thought of themselves, if they could be as honest as we were trying to be. But that was not the true purpose of these exercises. What we were really doing in creating all of these competition matrices was testing ourselves over and over again to see the SPCO’s situation through different lenses and to see if we were truly ready to address the reality of our position.

Remember, our instincts had told us there was something out of kilter between our “talk”—our vision statement—and our “walk”—the ways we really functioned as an organization in the many orbits in which we compete. These exercises were invaluable in solidifying the CRG’s understanding of where we stand and provided a critical platform from which to begin to build our fabulous future. These exercises also provided the first building blocks of safety in our meetings. Painting our competitive position in such an unvarnished manner did not mean that the SPCO isn’t a very good chamber orchestra. It just sharpened us up to tackle the challenge that we had set in the strategic plan in stating so boldly that our common aspiration was preeminence in our field.

The Nature of Artistic Leadership

Before we could focus fully upon a developing vision that described precisely the nature and scope of the life of a SPCO musician, we simply had to deal with an issue that has vexed our organization for many years: the institution of the music director. Since its founding in 1959, the SPCO has had five music directors: Leopold Sipe, Dennis Russell Davies, Pinchas Zukerman, Hugh Wolff, and Andreas Delfs. Briefly, between 1988 and 1992, the SPCO also undertook an important experiment in a different form of artistic leadership: the Artistic Commission, composed of three distinctly different musical leaders: Hugh Wolff (principal conductor), John Adams (creative chair), and Christopher Hogwood (director of music). In this seminal departure from traditional American artistic leadership models, the SPCO established new territory, completely consistent with its value imperatives of innovation and differentiation, as well as its multiple repertoire missions. But the Artistic Commission was disadvantaged by the organization’s failure to maintain continuity of board and management leadership. For more than thirty years, SPCO management and board leadership has changed on the average of every two to three years, contributing to inconsistency of vision and artistic points of view. In addition, the Artistic Commission simply redistributed among three conductors and the management the prior responsibilities of the music director, without addressing the opportunities the commission might have provided for musicians to play a more active role in their artistic future. The Artistic Commission was a vitally important experiment which ended during the financial crisis of 1993, when Hugh Wolff agreed, at the board’s request, to assume a reestablished traditional music directorship.

In the CRG, we struggled hard with the difficulties that have compromised the relationships the SPCO musicians have had with their music directors over the past 40-plus years. We struggled with how a fundamentally hierarchical and traditional music directorship fit with our desires to have the musicians own greater responsibility for the artistic outcomes.

We concluded that the music director, as an institution, justified or not, had become the lightning rod for the orchestra’s blocked artistic spirit. The music directorship had become the repository for too many of our frustrations, our blame, and our excuses for not achieving “the next level.” These frustrations, of course, were disproportionate with the “sins” of any music director, past or present; each has in fact brought a distinctive artistic voice and made important contributions to the orchestra. We began to understand that we would need to consider doing something dramatic to break this cycle.

We began to ask whether we should not learn from the conceptual strengths of the Artistic Commission and better understand why it had not quite worked. That learning might provide the springboard for unleashing the orchestra’s spirit. What we were getting at was that the traditional music director model for a symphony orchestra—in place at the SPCO for many years—was not appropriate for us and now seemed antithetical to the artistic aspirations of the SPCO. We came to the powerful conclusion that having a traditional music directorship was simply at odds with what we wanted to achieve at the SPCO.

This is not written lightly, for it flies in the face of 40 years of SPCO tradition and might also be seen to be disparaging of the five music directors who have devoted enormous time, energy, and talent to the SPCO during their tenures. On the contrary, we all value the many contributions of our music directors. We were, however, now actively questioning how the positions they had held had brought the unintended consequence of stifling the artistic spirit of the orchestra.

Indeed, Andreas Delfs, appointed to the SPCO music directorship in 2000, quietly and thoughtfully behind the scenes, encouraged us—and in so doing gave us permission—to think of our future differently and without a traditional music director. Presciently and astutely, Delfs intuited both the spirit of the SPCO musicians and the structural nature of the problem. He suggested to us that we should fully explore various models for artistic leadership that envisioned shifting responsibility for many artistic matters from the music director to the musicians and staff. Delfs deserves enormous credit for his leadership in this, and for his selfless understanding of the SPCO’s dynamics.

Thus, an important conclusion of the CRG was that the power dynamics of music director and musicians had to change. Because the notion (somewhat mythological, but nonetheless real in our culture) of music director “power” was antithetical to the idea of unleashing the spirit, there was another very important dimension to our conversations: power vested in the music director was responsibility removed from musicians. We came to believe that if charged with far greater responsibility for artistic matters, our musicians would rise to the occasion. Ultimately, we decided together that the best path for the SPCO was to do indeed that: vest the musicians of the SPCO with the greatest possible responsibility for their own artistic future by transferring many of the music director’s “powers” to the musicians themselves, transforming the SPCO’s music directorship into something more akin to the position of principal conductor. While not uncommon in Europe, this system scarcely exists in America.

We also knew that whatever its official name, the concept of multiple leadership, so thoughtfully and brilliantly embodied in the Artistic Commission 15 years earlier, could vibrantly address the challenges of the SPCO’s multiple repertoire missions. We concluded that the near-term transformation from a music directorship to a principal-conductor model might even lead farther as our organization developed.

So, could the SPCO devise a different leadership model? Yes. Provided board and managers were willing to develop greater continuity and, more importantly, to delegate to the SPCO’s most stable constituency—its musicians—substantial responsibility for many of the duties of the music director. And further provided that the musicians, trained otherwise, and channeled by culture away from the difficult choices and decisions inherent in artistic leadership, would take up the mantle.

We’re not entirely sure yet what this means. But certainly it means that just as the job descriptions for musicians in the SPCO are now radically different from those of musicians in nearly every other orchestra in America, so too will the job descriptions of conductors with whom we have important relationships change radically. During the course of the next few months, we expect to develop the form that new podium leadership should take.

Does this mean we expect the orchestra to vote on every artistic decision? No. We have delegated that decision-making responsibility to a pair of joint musician-management committees called the Artistic Vision Committee (responsible for artists, repertoire, tours, media, etc.) and the Artistic Personnel Committee (responsible for auditions, tenure, dismissal, leaves of absence, seating, rotation, etc.). This shift will require much adjustment on everyone’s part.

Does it mean that the conductors have no say? No, but it does mean that they need to work directly with the two committees, and that together, we will reach decisions.

The hardest aspect of this change will be the leadership challenge for our musicians, which is, quite frankly, new and somewhat controversial within the field at large. Musicians serving on our two artistic committees are indeed working directly with the staff to make many decisions about the SPCO’s artistic future, about everything from who is in the orchestra to what conductors, collaborators, and soloists we engage, to the orchestra’s long- range artistic planning. There will be tension between traditional roles and these new ones; there will be absence of an all-powerful music director against whom to push; there will be tension between decision making based on good personal judgment informed by thoughtful discussion with the orchestra at large and mere “popular vote” representation of the orchestra’s views; there will be tension between one’s artistic responsibilities and the responsibilities of friendship and collegiality. There will be tensions and stresses innate for anyone (conductor, musician, or manager) in undertaking these solemn responsibilities on behalf of the institution.

To the credit of the SPCO musicians, these challenges have been undertaken with vigor and a very true appreciation of all of these tensions. But we should not suggest in any way that there is unanimity on these matters. There is indeed anxiety throughout our organization about the implications of the path we have chosen; nevertheless, we have chosen that path, with our eyes open to its challenges and we have done so with a critical mass of people saying yes.

We don’t yet understand how leadership, decision making, critical mass, majority votes, and minority voices all interact. Truly! But kudos to a majority of our musicians for being willing to undertake the challenge! Kudos to Andreas Delfs for embracing this radical and open-ended view of podium leadership and for encouraging us to be bold. And kudos to the board for believing enough in our musicians to include them powerfully in decisions about all artistic matters.

There is much we don’t quite understand yet, and we may need help achieving that understanding. For example, will an idea die because someone objects? Does a concept become reality because a couple of “powerful” people think it should? Are we only to do what everyone agrees to? Where is the right place on the continuum between the two unacceptable poles of leaving decision making completely to the committees and throwing every decision open to the organization for a vote? We are committed through dialogue, process, and trial and error to find that right balance.

Acceptance of the idea that a lead conductor of a group of conductors could possibly act more like a principal conductor in a European orchestra means the orchestra really has to acknowledge its responsibility for its artistic future and its artistic quality. It also means staff members must “come out of the closet” on artistic issues, bursting mythologies that managers play little or no role in shaping artistic results.

The ramifications of all this were broad and deep: the myth of music director “power” was shattered; the role of the musicians in the artistic decision making at the SPCO was redefined with broad responsibilities; the staff’s artistic responsibilities were more out in the open; and critically, the board’s responsibility to be responsive in hiring artistically proficient management in the future became paramount.

In short, these discussions implied seismic shifts of dynamics within our organization.

◆ No longer can the music director be praised or blamed for the results;

◆ No longer can the staff “pass the buck” on artistic successes or failures to the music director; and

◆ No longer can the musicians consign responsibility for the artistic results to the music director.

Thus, through changes to our contract, our musicians’ roles in the artistic future of the orchestra shifted from passive to active.

Leadership Evolution: From Directorship to Partnership; from Duties and Authorities to Responsiveness and Responsibility

In conceptualizing a structural framework for SPCO artistic leadership, we grounded ourselves in the concept that the SPCO would play its best—in its various repertoire missions—when led by specialists in their fields and when led by “play-and-conduct” collaborators making music interactively with the orchestra. This means making careful choices, but it also means removing power from the equation of artistic collaboration. We do not wish to remove inspiration or desire to please or being worked hard from the equation, but we certainly want to remove fear and power from it. Hence our choice of language to describe what we sought in our relationships: partnership, not direction; responsibility for, not authority over.

As we have begun to develop our concepts for podium artistic leadership, we have asked ourselves some litmus-test questions:

◆ Do our concepts serve to engage the orchestra meaningfully in the business of key artistic leadership functions of programming, choice of collaborative artists, and selecting and developing SPCO members?

◆ Are they clear about which responsibilities have been transferred from the conductors to the musicians and senior management?

◆ Do our concepts provide the opportunity for motivated SPCO musicians to become deeply involved in planning and developing the artistic future of the chamber orchestra?

◆ Can we function in real time?

◆ Do they allow for the possibility that the artistic profile and spirit of the orchestra will be a reflection of the orchestra’s players’ spirit rather than a reflection of one person, e.g., a music director?

◆ Will it be possible —in the absence of a traditional music director— for the SPCO to develop several strong artistic relationships with important conductors and soloists?

The answer to all of these questions, in our minds, is a resounding yes, but with some cautionary notes—the most prominent of which is, at this writing, that we have not completely settled on precisely what form this leadership should take.

◆ Decision making is inherently difficult—perhaps dangerous—in committees; learning to find the balance between judiciously seeking and incorporating input from the orchestra, and simply doing something because someone suggested it will be a steep challenge; we will have to learn to be decisive and courageous in our choices.

◆ Developing working relationships in our Artistic Vision and Artistic Personnel Committees (which will allow for strongly held opinions to be voiced and disagreement to be expressed with safety) will require patience and a willingness to learn new methods of interacting with each other.

◆ The SPCO will have to be more aggressive than ever in pursuing artistic relationships with conductors, collaborators, and soloists.

The “Stuff” Phase

Having grappled with really tough issues about our competitive position, our spirit, and the fundamental structure of artistic leadership, we now turned our attention to the real “stuff” of the contract. We set about developing a vision that described what a SPCO musician actually does, or needs to do, and how much of that “stuff” should be outlined in the contract.

In the CRG, we decided that we had to present our colleagues in the orchestra with a bold vision of what life in the SPCO could be like if we had the courage to move the orchestra, board, and artistic leadership in that direction. We knew that the SPCO musician’s life we envisioned was not described in the current collective bargaining agreement. We knew that simply changing the current collective bargaining agreement would not fly. And yet we were determined to give this new vision a chance, without unduly threatening members of the orchestra who thought that things were just fine as they were. Here, Paul Boulian and Fred Zenone came to the fore, proposing the idea of presenting a vision of the orchestra in 2010—a date far enough away to both provide comfort for those who thought this was too radical and to allow our thinking to be abstract. It was a brilliant idea. Thinking about 2010, rather than next year, was liberating for all of us. “In 2010, we can be X. In 2010, we can be Y. In 2010, we can be anything we want to be.” The ideas flowed, quickly and fluidly, from musicians, trustees, and staff alike. If someone was uncomfortable with an idea someone else expressed, the immediate retort of the group became: “Yes, but this is 2010!”

We started thinking about what a SPCO musician really needs to do to be a member of our orchestra. A few things became clear quickly.

A SPCO musician needs:

◆ first and foremost, to be a superior instrumentalist;

◆ to have time and energy to practice;

◆ the stimulation of playing great music with wonderful colleagues, led by inspiring musicians;

◆ to play chamber music—a lot of it—to maintain ensemble skills at the highest level, and more importantly, to be inspired by that music’s inestimable pleasures;

◆ to have an outlet for individual artistic interests—teaching, solo performance, composing, arranging, conducting, and perhaps other activities;

◆ to have the opportunity to grow artistically, stimulated by formal and informal feedback;

◆ to be challenged to be better, through the demands of repertoire, organizational culture, or individual drive;

◆ to understand what is going on in the larger environment of the orchestra world (listening, reading, observing);

◆ to know what is going on in the SPCO organization, its opportunities, and its challenges.

In short, SPCO musicians need and deserve a lot!

As members of the CRG, we had an obligation to figure out how to develop a collective bargaining agreement that answered these needs and truly reflected, allowed for, and compensated for this wide range of needs. This was especially true because we had already agreed that the SPCO’s success in achieving its goals depends on our musicians doing all those things extremely well. We simply cannot succeed without the invaluable resource of the orchestra itself striving constantly for peak performance. We had a duty to create the conditions for that to happen.

By New Year’s, we had reached a fair consensus about what the 2010 vision looked like, and we were eager—and apprehensive—about sharing it with the full orchestra, which we did on January 23, 2003, in a six-hour retreat. The full vision document that we shared is available at the Institute’s website. In the vision document, which was elaborately edited, we sought to define our work so far in a way that the orchestra could begin to understand and begin to challenge the results. The vision document did not in any way attempt to be a collective bargaining agreement; rather, it described our agreed-upon views about the roles and responsibilities of musicians, staff, and board within the broader SPCO organization, and went on to describe, subject by subject, what we thought the specific responsibilities of SPCO musicians should be (in 2010).

The members of the CRG were all quite nervous about the January 23 retreat, and there was understandable concern that the first meeting of the orchestra during which the negotiating committee was to explain the direction of our work would be made even more challenging by our intention to have the entire CRG—musicians, trustees, staff, and consultants—in attendance. Finally it was decided that trustees, managers, union representatives, and consultants would sit in a second row behind the orchestra members, who were seated around a large rectangular table. The setup was the idea of the musicians in the negotiating committee, and it worked brilliantly. Nearly all of the orchestra members attended, and all but three of those in attendance participated vigorously in the six-hour discussion. The participation was perceptive and thoughtful.

Prior to the January 23 orchestra meeting, the CRG worked to understand the purpose and desired outcomes of the meeting. Using the format we had developed in our 2010 vision statement, we developed a vision for the January retreat:

The purpose of the January 23 retreat is to engage the SPCO musicians collaboratively in the renewal process in a way that builds trust and allows their voice to be heard; opens them to the possibilities; makes them feel free to express their fears and misgivings so that the musicians can embrace the ideas of the 2010 Vision and have enthusiasm for implementing as many of them as possible as soon as possible.

We also outlined what we considered to be the desired outcomes of the retreat:

◆ That SPCO musicians might see the advantages of this new approach.

◆ To help SPCO musicians begin to think in terms of principles and beliefs, rather than in terms of rules and regulations.

◆ To encourage SPCO musicians to think about unleashing their spirit.

◆ To create a sense of possibility about the future.

◆ To provide the CRG with new ideas to enhance the process.

◆ To encourage the CRG to “go for it.”

◆ To build confidence in this process and its participants.

◆ To gain an increased commitment for musicians’ involvement.

There were several key concepts we wanted to share and to test with the musicians because they were the core elements of our 2010 vision. These concepts had to do with the scope of work and aligning what the collective bargaining agreement provided with the demands of the strategic plan. The CRG agreed that SPCO musicians had three kinds of responsibilities: core artistic responsibilities, core organizational responsibilities, and affiliated responsibilities. The latter included such items as concert programming discussions and planning; tour discussions and planning; rehearsal and concert hall scheduling; and chamber music, small ensemble, and orchestra casting assignments. Each SPCO musician would be expected to participate in some affiliated activities, with the explicit understanding that no musician would be required to participate in any particular activity. We also shared our belief that the SPCO contract had to contain provisions for a more complete audition and player-selection process, a more rigorous tenure review, significant revisions to the musician-dismissal process, and, most importantly, the contract had to create a platform for consistent and ongoing feedback for every musician of the SPCO.

If we could establish agreement around these concepts of responsibility, then the CRG would have clear direction about its work. During the retreat, there seemed to be agreement, with some musicians objecting to some ideas, others supporting them vocally, and others just asking lots of questions. But the CRG had its fundamental answer: to forge ahead. At the end of the retreat there was some powerful testimony. One long-standing member of the orchestra said, “I joined this orchestra believing that what you have just described was what my future looked like, and I have been waiting 25 years for it to come true.

We must find a way to make this happen. I am only sorry that I will soon be retiring and won’t be here to enjoy it.”

We had our answer from the orchestra. We had fervently hoped that the SPCO musicians would embrace our work sufficiently to send us the signal to keep going. The retreat was a remarkable event, and by the end of the day, after musicians and the negotiating team met alone, there was a clear set of signals sent by the orchestra: keep going, tell us more about what this means in contract-specific, concrete terms; respond to some of our biggest concerns; and keep us informed of what is going on.

There were many questions of how, how fast, and to what degree. But there was no longer a question of whether. We were all committed to bringing 2010 in some form into 2003. We felt that we had passed a major milestone in our work.

Tough Financial Developments: A Major Intrusion

When we began the contract renewal process in August 2002, the SPCO had just completed its ninth consecutive year with a balanced budget. While celebrating that remarkable accomplishment, everyone also knew that balancing the budget had been extremely difficult to achieve in each of those nine years, particularly the last two. We spoke often of the fact that balanced budgets did not imply financial stability. Further, even comparative financial stability did not imply financial robustness, which we defined as the ability to invest tangibly in the artistic and organizational development of the SPCO. For precisely these reasons, our 2002 strategic plan had explicitly outlined the need for $50-60 million in endowment, and an additional $12-15 million in special funds to sustain the organization over the next few years.

However, no one in the organization had accurately anticipated the impact that the economic downturn of 2002-2003 would have on our ability to sustain the SPCO’s basic revenue structure. Accordingly, as we entered the contract renewal process, we had relatively high confidence that money discussions would be of secondary importance to “stuff” discussions. We all expected modest cost-of-living increases to be part of the settlement.

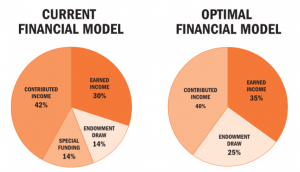

Right around New Year’s, the SPCO received a series of serious financial setbacks that not only threatened the financial well-being of the orchestra, but also threatened to undermine our contract renewal process. During the 30 days between December 20 and January 20, more than a million dollars in projected foundation support evaporated for the current fiscal year (FY03) and for the two years following. Simply put, the SPCO for several years had been quite heavily dependent on special foundation support (over and above annual fund and endowment-draw support) to balance its budget. Largely due to the recession that began in 2001 and the attendant stock market declines, expected foundation giving and the SPCO’s own endowment draw would be drastically reduced from both budget and long-term projections.

We knew by the end of January, immediately after our retreat, that this financial challenge was of an order of magnitude and character altogether different from those the SPCO had faced annually since 1993. The evaporation of expected foundation support was deep enough that, when combined with annual-fund challenges and endowment-draw limitations, it became quickly clear that “just increasing revenues” would be a flawed response. Reducing expenditures was the only recourse.

This was a major blow, dispiriting and discouraging. It felt to all of us like “déjà vu all over again.” But it was real. Responsible stewardship of the institution demanded an aggressive and immediate response. We began with a thorough discussion of the SPCO’s finances, its sources of revenue, and its categories of expense. Over our next 10 or so meetings, we dealt extensively with all aspects of the financial circumstances of the SPCO. Some of those meetings lasted as long as eight hours. We also did our best to share the financial information completely with the orchestra. The orchestra also received formal presentations about financial planning, endowment management and planning, and the full scope of marketing, public relations, and development programs. Within the CRG, everyone became satisfied that the numbers and analysis were real, and that the framework for our work on compensation needed to be that of significant cuts, not cost-of-living increases, or a wage freeze.

Within the CRG, we eventually agreed that an overall organizational cut of 15 to 20 percent was required; more broadly, the executive committee, finance committee, and senior staff concurred. In late February, we reduced the size of the staff by 10 positions, a 25 percent body-count reduction. Significant other cuts were made to the FY03 budget in an attempt to reduce the size of the projected deficit. Senior management took an immediate 10 percent pay cut.

There was agreement within the CRG that the orchestra should participate in expense reduction; there was agreement that it should be fair and proportional, and that it should be matched by senior managers and the artistic leadership. There was also an expectation that the guest artistic budget would be reduced by at least 10 percent. The challenge was to weigh all of the many variables and their differing impacts on orchestra musicians individually, the orchestra collectively, the staff individually and collectively, and the overall ability of the SPCO organization to continue to deliver very high-quality concerts to the community. Obviously, the retention and recruitment implications for both staff and musicians were of paramount importance, since approximately 60 percent of SPCO expenditures are tied to fixed expenses.

Together we ran many different scenarios, testing the many implications of solving our problem one way or another. We looked at differing levels of orchestra participation, staff participation, program and promotional budget participation, and ultimately settled on a target amount for the orchestra, which formed a frame of reference for making our choices.

During these many hours of meetings, staff and board members disagreed openly with each other; board members disagreed with each other, as did staff and musicians alike. It was painful for everyone. We ultimately settled upon an 18 percent reduction in SPCO orchestra costs, including salaries, benefits, and the costs of extra and replacement musicians. The staff as a whole took a 23 percent cut. Some within the senior management volunteered to take second cuts to match the orchestra percentage.

This is not the place to debate whether we made the right choices, for we will really only know the answers to those questions five to ten years from now. No one can accurately predict how the most important factors, recruitment and retention, will play out. However, the CRG believes that it made thoughtful and responsible choices for the institution, knowing as we did that the choices we made during this process would have direct impact on the SPCO’s ability to achieve its stated goals, positively or negatively. The stakes felt very high to all of us.

Paul Boulian and Fred Zenone were helpful in devising the right exercise through which to frame our choices. We divided into groups, with each group to consider one of four possible outcomes: insolvency, survival and status quo, progressing, and thriving. We then defined the conditions that would lead to each scenario, the implications of each, and the likelihood of each. We then tested our beliefs about financial stability. In the short term (2003-2006), we agreed:

◆ That we must accept the reality of a deficit in 2002-2003.

◆ It is fundamental that the SPCO have balanced budgets aggregated over the three years from 2003-2004 through 2005-2006.

◆ That the SPCO must make major progress on endowment funding.

◆ That there be no accumulated deficit at the end of 2006.

Which, in turn, led to an important discussion: what was the relationship between the need to reduce orchestra costs and the expansive discussions we had just completed in drafting the 2010 vision? It was a complex and delicate conversation, and one that ultimately concluded with the CRG’s consensus: if we truly believed that the 2010 vision was vital to the future of the SPCO absent the current financial difficulties, it was equally, if not more, vital to our future given the financial difficulties.

The exercise showed us that we had to forge ahead. Insolvency was an unacceptable result, and the status quo, while possibly more comfortable in the near term, ultimately led, in our view, to insolvency, and was therefore unacceptable. Progressing and thriving were the only two acceptable scenarios, and each required action on the 2010 vision and the strategic plan to stimulate the financial interest the SPCO requires in ticketing, the annual fund, special funding, and endowment funding. Progressing and thriving were our bridges to the future. But we could not progress or thrive if we lived too close to the edge financially, supported by too much as yet unsecured and precarious special funding. Cutting expenses in the right places and putting in place the contractual aspects of the progressing and thriving scenarios was, we agreed, the best path to pursue.