Issue No. 15: October, 2002

Publisher’s Notes by Fredrick Zenone

Paul R. Judy Awarded Gold Baton

About the Cover by Phillip Huscher

The Wolf Report and Baumol’s Curse: The Economic Health of American Symphony Orchestras in the 1990s and Beyond by Douglas J. Dempster

Orchestra and Community: Bridging the Gapby Penelope McPhee

Collaboration and Transparency: The Oregon Symphony Music Director Search

Explorations of Teamwork: The Lahti Symphony Orchestra by Robert J. Wagner and Tina Ward

Field Activities and Research

Improving the Effectiveness of Small Groups within the Symphony Organization by Robert Stearns

A New Avenue for Musicians’ Outreach: Music and Wellness by Penny Anderson Brill

Book Review: by Robert C. Jones, William L. Foster, Margery S. Steinberg Leading Teams: Setting the Stage for Great Performances

Publisher’s Notes

Once again, America’s symphony orchestra community is in a state of heightened anxiety about the fiscal condition of many of our orchestras. Over the past two years, worrisome fissures have surfaced in some of our gold-standard organizations, and in some smaller orchestras, these fissures appear to be of life-threatening proportions. From time to time, perhaps with a sense of déja vu, it can be helpful to take a long look backward in order to see ahead more clearly. What have we learned? Are we repeating mistakes of the past? Did we ask the right questions in the past? Are we asking the right ones now?

In the world of the performing arts, it is sometimes said—quietly to be sure— that members of the academic community do not understand, or perhaps care very much, about our world of applied arts. But there is increasing evidence that there are thinkers who are committed to using academe’s unique resources and position to influence policy and cultural affairs.

Douglas J. Dempster is such a citizen of the academy. Doug is currently senior associate dean of fine arts at the University of Texas at Austin. He formerly served as dean of academic affairs at the Eastman School of Music. There he created the Orchestral Studies Program in collaboration with the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra. He is committed to developing orchestra musicians who are not only accomplished performers, but who also have an awareness and curiosity about our orchestra organizations as institutions. For years, he has included the Wolf Organization’s report, The Financial Condition of Symphony Orchestras, as part of his curriculum.

In 1990, the American Symphony Orchestra League commissioned the Wolf Organization, Inc., to study the financial condition of America’s orchestras. Thomas Wolf delivered the findings of that study during the League’s 1992 conference, and ever since, the study has been referred to throughout the industry as the “Wolf Report.” It was for years the subject of vigorous debate, not only for what its implications seemed to be for the future, but also for some of the Wolf Organization’s hypotheses for future change. In this issue of Harmony, 10 years after the Wolf Report’s publication—Doug Dempster, having the perspective afforded by time and the advantage offered by the extensive discussion the report initiated—takes a new look at the study. It is a serious look, it is thoughtful, and it is provocative.

The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation has a long history of being among the most interested and generous supporters of the performing arts and the manner in which arts organizations relate to their communities. Ten years ago, the Knight Foundation began to consider a new initiative which, two years later, became known as the “Magic of Music.” At yet another 10th anniversary, the Knight Foundation, in order to see ahead more clearly, is having a good hard look at what its funding has accomplished.

Penelope McPhee is the foundation’s vice president and chief program officer and occupies a learned place from which to comment on the field of symphony orchestras. In April of this year, Penny delivered a speech to a convocation of Knight orchestra grantees in Portland, Oregon, and we are pleased to share that speech with Harmony readers. She is eloquent about lessons learned and she brings a sobering reality to those lessons. She conveys the foundation’s deep commitment to our art and to our organizations. Transformational change is slow and difficult, but it must happen. Sometimes difficult lessons feel like tough love.

Two years ago, in Harmony #11, members of the Oregon Symphony family shared with enthusiasm the results of their work to change their organizational practices. In this issue, we again converse with members of that organization about their recently concluded search for a new music director. They make a compelling case that the changed practices have taken the organization to an even higher level of participation in making important decisions. Their search process provided for broad participation and meaningful delegation of responsibility, and fostered a level of energy they say would not have been possible otherwise. Bravo to the Oregon Symphony for finding a unique process that worked so well for them as they searched for a new music director. And our thanks to roundtable participants Niel DePonte, Kathryn Gray, Lynn Loacker, Mary Tooze, and Tony Woodcock for sharing the story.

Some participants in and observers of our industry think symphony organizations ought to be structures created to allow artists to go about their art without concern for more secular matters. They often describe the seemingly “ivory tower” conditions of European orchestras for which, historically, private funding has not been an issue. Robert Wagner and Tina Ward are American symphony orchestra musicians who thought we might all learn something by observing the practices of a selected group of European orchestras. Funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation made it possible for Tina and Bob to visit with members of those orchestras to learn firsthand about their organizations. One of the orchestras they visited was the Lahti Symphony Orchestra in Finland. There they found some enlightened practices which were made even more interesting to the Institute by the fact that Osmo Vänskä, the chief conductor in Lahti, is the music director designate of the Minnesota Orchestra. My reaction to Bob and Tina’s Lahti discovery is a new resolve to watch developments at the Minnesota Orchestra closely.

Many of the positive organizational change practices that have been put forward in Harmony have involved initiatives undertaken at the overall- organization level. In Harmony #7 and Harmony #11, Robert Stearns related the success he had demonstrated as the “Hoshin guru” of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. But Bob has a more diverse tool kit. In this issue, he shares ways in which organizational change can also proceed from microcosm toward macrocosm. If a single constituency within an orchestra organization seeks ways to function more effectively, the efforts can eventually permeate the overall organization. Bob uses specific examples from projects he has facilitated to elaborate on this thesis.

In this issue’s final essay, Penny Anderson Brill brings to our attention a way in which bad personal news led to leading-edge organizational practice. We each try to deal with personal crises as best we can while continuing our commitments to our work and to those with whom we work. Penny, an orchestra musician, did better than that. She addressed a serious illness by engaging her deepest discipline and need for music with her longtime participation in the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra’s evolving organizational practices. The result has been a remarkable discovery of yet another way in which an orchestra can serve as a valuable community resource.

From time to time, the Institute recommends new publications we think have relevance for our readers. J. Richard Hackman, a professor of social and organizational psychology at Harvard University, has been a friend of the Institute from its beginnings. In the Institute’s earliest years, he chaired the Research Advisory Board. Richard has published important research about symphony organizations internationally and continues to be a vigorous observer of symphony orchestra organizations in the United States. In July of this year, Harvard Business School Press published his new opus, Leading Teams: Setting the Stage for Great Performances. It is not a book about symphony organizations, but as I read it, I began to feel—as a lifelong member of symphony organizations— that maybe Richard was speaking to us, too. At the Institute, we thought we should test my reaction. We invited three people to review Leading Teams—one from the vantage point of an experienced executive director, another from that of an orchestra musician, and a third through the lens of a former board chair. We thank Robert Jones, William Foster, and Margery Steinberg for their thoughtful commentary.

On page 54, we update information on the Institute’s field activities, and on the conclusion of the Conductor Evaluation Data Analysis Project (CEDAP). On page 78, we report the financial status of the Institute for its most recent fiscal year.

If you read music, you have probably identified the score fragment on the cover of this issue of Harmony, at least in its most well-known form. But can you identify its full orchestral connection? And identify what the composer and the Institute’s founder have in common? Phillip Huscher explains all beginning on page xiii.

In the pages immediately following these notes:

◆ We celebrate Paul Judy’s receipt of the Gold Baton award during the American Symphony Orchestra League’s national conference.

◆ We acknowledge and extend our heartfelt thanks to the nearly 160 symphony orchestra organizations that have offered support of the Institute’s activities this year.

◆ We recognize the commitment of individuals from every constituency of North American symphony orchestra organizations who have made contributions to the Institute as Advocates of Change.

In the course of these notes, I have twice referenced others who have looked back in order to move forward. As the Institute enters its eighth year of activity, I have done a bit of looking back myself. The list of individuals who have authored material for Harmony is long and distinguished. The publication’s readership is loyal and encouraging of our efforts. The list of those who have served on the Board of Advisors includes some of the most forward-thinking participants in the industry. The list of orchestra organizations that have undertaken serious organizational development activities is showing signs of growing exponentially. I extend a personal thanks to each of you who has contributed to and guided the Institute’s work for the past seven years. While not discounting those worrisome fiscal fissures I mentioned in the opening paragraph, we now look ahead to continue those activities that the Institute does well, to discard a few noble experiments that have failed, and to direct our energies toward the continued development of our symphony orchestras as effective organizations.

During the 57th National Conference of the American Symphony Orchestra League, which was held in June in Philadelphia, Paul R. Judy, founder and chairman of the Symphony Orchestra Institute, was awarded the League’s Gold Baton.

The award, the League’s highest, has been presented annually since 1948, and honors distinguished service to music and the arts. The Gold Baton recognizes institutions and individuals whose contributions to the American orchestra world extend beyond a single orchestra to influence and advance the cause of orchestras and symphonic music throughout the country. Past recipients include Leonard Bernstein, Pierre Boulez, Carnegie Hall, Aaron Copland, and Isaac Stern.

Paul Judy formed the Institute in 1995 to foster positive change in the ways symphony orchestra organizations function, to enhance their value in their communities, and to help ensure their preservation as unique and valuable cultural institutions. In December 2001, he stepped back from the Institute’s day-to-day activities, but continues as the organization’s chairman.

The award was presented by Robert Levine, principal violist of the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra and, at the time of the presentation, chair of the International Conference of Symphony and Opera Musicians (ICSOM). Robert’s words of presentation and Paul’s words of acceptance follow.

Robert Levine:

It is a great honor to be able to present this award to Paul. I have presented batons before, generally to conductors who accidentally lobbed them in my direction. But I’ve never been happy doing so; it feels too much like giving them a second chance to hit the target.

I first met Paul Judy in 1994, when he was visiting orchestras and people in the field to learn about the state of our business and to figure out what he could do to make a difference.

Three things struck me about him, aside from the obvious force of his personality. The first was that he asked good questions, the kind of questions that were hard to answer because they were questions I should have been asking myself, but could not see clearly enough to do so. The second was even more unusual; he listened very carefully and very intently to my attempts to answer those questions. It was actually quite daunting to be listened to with that degree of attention. The third thing that became clear to me about Paul was that he was driven not only by a desire to make a contribution to our field (which many of us share), but also by a curiosity about why things happen the way they do—a curiosity as strong as my own. It was as though I had just met another member of a very small secret club. Paul had, of course, a different perspective, in the strictest sense of the word, from mine. But the fascination with the uniqueness of our field was the same.

It’s been most interesting to watch the co-evolution of Paul Judy and his Institute. I’ve benefited directly from his search to find ways to influence the field for the better. Few musicians get to work with their fathers so publicly as Paul invited my father and me to do in the pages of Harmony. It was an opportunity that meant even more to my father, perhaps, than it did to me, and something for which I will always be grateful.

It was probably inevitable that someone with Paul’s long history of making things happen, rather than simply studying why things didn’t happen, would move towards an active effort to encourage change. And it was equally inevitable that, with his fascination for organizational dynamics, the change that he would try to encourage would be systemic institutional change, rather than just trying to show us how to do what we were doing better than we had.

When we talk about institutional change, it’s important that we try to understand why we should talk about change at all. It’s easy to turn change into a panacea. In a sense, it’s a truism that, as the bass sings in the great aria in part three of the Messiah, “we shall all be changed,” whether we wish it or not. But the kind of change that Paul and the Institute study and work toward is not a panacea, nor is it inevitable. In some ways, orchestras are among the most static institutions in Western civilization. I have no doubt that if I were transported back in time to, say, the premiere of a Beethoven symphony and handed a viola, I could sit down in the viola section and manage not to get noticed for at least a movement or two. Of very few professions or institutions in Western society could that be said.

We have some profoundly successful and stable orchestras in this country that, frankly, don’t need to change to survive; they will survive anything short of a large asteroid. And we have a few orchestras which no conceivable institutional change will rescue from a permanent state of crisis or worse. For some orchestras, institutional change is a necessary condition of survival. But the others either don’t need it to survive or it won’t help.

And for no orchestra is institutional change a sufficient condition for survival. Such change—if successful—will make orchestras easier to lead. But it will not obviate the need for leadership, on all levels and within all constituencies. Leaders may be made and not born, but the making is still a black art at worst and a very labor-intensive process at best. I learned most of what I know about leadership from spending almost two years in the pocket of a very gifted labor leader during a horrible period in my orchestra’s history. The rest I learned from making lots of mistakes and getting very frank feedback from those who were affected by them. Is there any other way to learn leadership except lots of practice and one-on-one instruction?

The real imperative for institutional change isn’t, at the end of the day, practical; it’s a moral imperative. There is a scene in a book I grew up with that makes this point wonderfully. The book is Hornblower and the Atropos by C. S. Forester. The scene is one in which young Captain Hornblower has just been presented to the King by Admiral Lord St. Vincent, First Lord of the Admiralty. Hornblower is taking his rather nervous leave of St. Vincent.

St. Vincent stood looking at him from under his eyebrows.

“The navy has two duties, Hornblower,” he said. “We all know what one is—to fight the French and give Boney what for.”

“Yes, my Lord?”

“The other one we don’t think about so much. We have to see that when we go we leave behind us a navy which is better than the one in which we served. . . . Choose carefully, Hornblower, if it ever becomes your duty. One can make mistakes, but let them be honest mistakes.”

I believe we have a moral obligation to leave our orchestras better than we found them—especially when there’s so much room for improvement. And that means we need to change our institutions. Just looking from where I sit, we’ve created workplaces where orchestra musicians enjoy a living wage or better, wonderful benefits, lots of time away from the workplace for leisure or other professional pursuits, and tremendous job security. We owe a great debt to those who made this possible—board members and funders working together (although some would be surprised to hear it) with the trade union activists among us who practiced activism when it was very unpopular with our employers and even our own union.

But what we haven’t created is a workplace that the musicians enjoy. And given the nature of the work—using the skills we learned for the sheer joy of playing to experience some of the greatest creations of the human mind—that is quite sad. If I don’t speak of the equivalent challenges and waste of human potential among staff members, volunteers, and even those who stand above us with baton firmly in hand, it is only because I don’t fully understand them.

So there is lots to do yet, even within the limits posed by the fundamental nature of the orchestra (not to mention human nature). But one more thing needs to be remembered if we are to be successful. Ken Pfaff, head of Teamsters for a Democratic Union, told the first-ever joint conference of the American Federation of Musicians’ Player Conferences in 2000: “Union reform is not a sprint; it’s a marathon.” Institutional change, like playing an instrument, is a wonderful topic for daydreams. Making it happen, just like getting to Carnegie Hall, takes lots of time and lots of work, some of which will be far from enjoyable. Paul’s personal commitment to the future of the Symphony Orchestra Institute is the same message of endurance and commitment simply said in a different language.

But as systemic institutional change comes to our field, I believe few will be seen to have been more instrumental in making it happen than Paul Judy and the Institute that he created. With that in mind, before I actually hand over the Gold Baton to Paul and you all give him the applause he so richly deserves, I would ask you to consider a more concrete gesture of support and appreciation. I would suggest you visit the Institute’s website, as I did a few months ago, and join the Advocates of Change. It’s a small step for an orchestra manager or a board member or a musician. But, if enough of us do it, it will begin to look like a giant step for our field.

Congratulations, Paul, and thanks.

Paul R. Judy:

My thanks, Robert for your thoughtful words and your long-time support of the Institute. And thanks, too, to Henry Fogel and the League board, as well as Chuck Olton and the League staff, for their roles in selecting me to receive this award. My thanks also go to Neil Williams and Cathy French for their early support of the Institute and to Fred Zenone for his long assistance, support, and succession in the work of the Institute.

I am very pleased, flattered, and humbled to receive this award! I do so on behalf of all symphony organization participants in America and Canada who are dedicated to healthier, more personally and professionally rewarding, more effective, and more sustainable symphony institutions.

You in this room—and all other attendees to this League conference—compose an important portion of that dedicated group. You are joined by many other symphony organization participants who are not with us today, especially many key board members and orchestra musicians. All together, we must find ways for symphony institutions—as total networks of employees and volunteers—to become more collaborative, more collegial, more inclusive, more robust, and more joyful.

The symphonic institution, as a central musical arts organization, is vital to the cultural development of its community. We must advance this cultural development. To do so, we must become advocates of organizational change, adaptation, and innovation. We must question and challenge many inherited and imbedded patterns of symphony organizational behavior, practices, policies, and structures which reduce our effectiveness and sap our strength. We must find fresh and invigorating alternatives.

We must find ways to unleash the enormous levels of intelligence, energy, and passion which exist in our symphony organizations. Organization development principles and methodologies to help in this process of change have already been created. We must study, understand, and then apply these insights to the wonders and complexities of the symphonic workplace and to the range of activities and community services which flow from it.

We can handle this challenge. We have the human capacity to change, individually and organizationally. Some organizations and participants are already in the process of doing so. Others are on the verge of action. Let’s broaden and accelerate this progress! We can do it! Or, perhaps more directly, you can do it!

Once again, my very warmest thanks for this wonderful award!

About the Cover

If you look closely at the score on the cover of this issue, you will notice a fanfare woven into a page of symphonic music. The fanfare is one of America’s best-known pieces, Aaron Copland’s Fanfare for the Common Man, and the symphony is his Third, which Leonard Bernstein called a great American landmark, “. . . like the Washington Monument or the Lincoln Memorial.”

Copland wrote the fanfare first, in 1942, on a commission from the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra—he was one of ten composers asked for works to begin each of the orchestra’s concerts that season. The other nine fanfares are now forgotten, but Copland’s quickly became one of his signature

pieces. It has enjoyed many lives, from wartime morale-booster to television theme music, and it still knows no peer when it comes to conveying uplifting, spine-tingling patriotism. (It has also inspired its own “feminist” sequel in Joan Tower’s series of Fanfares for the Uncommon Woman.) But Copland knew that it was too good to be doomed to the existence of a mere curtain-raiser, so he put it to good use to open the finale of his Third Symphony, his major postwar composition.

Copland’s fanfare belongs to the long tradition of short pieces composed to open concerts, dedicate buildings, crown royalty, launch military battles, start stag hunts, announce presidents, and, in general, make a festive noise for a special occasion or person. He dedicated his fanfare to the everyday people among us who, each in his or her own way, make extraordinary things happen.

And so why have we picked Copland’s fanfare for this issue? It is our way of paying tribute to Paul Judy, the latest recipient of the American Symphony Orchestra League’s Gold Baton, which Copland himself received in 1978. Paul is, of course, a man of decidedly uncommon strengths and ideals, from his grand vision of a Symphony Orchestra Institute right down to the idea of putting a piece of orchestral music on the cover of Harmony when he founded this publication in 1995. Paul, this fanfare’s for you!

EDITOR’S DIGEST

The Wolf Report and Baumol’s Curse: The Economic Health of American Symphony Orchestras in the 1990s and Beyond

A decade ago, the report of a study commissioned by the American Symphony Orchestra League was presented during the League’s

national conference. The subject matter of the study, and the report, was an analysis of the economic status of the symphony orchestra industry in 1991. Harmony readers who were involved in the industry at that time will recall the hue and cry prompted by “The Financial Condition of Symphony Orchestras.”

Author Douglas Dempster, in the pages that follow, revisits the 1992 report. He begins with a recapitulation of the report’s history and conclusions. He then adds to the mix an explanation of “Baumol’s Curse,” the classic analysis of performing arts economics published in 1966, and an underlying tenet of the report’s conclusions.

The author next fast-forwards to the current year and inquires, “Where does the orchestra industry find itself 10 years after Thomas Wolf’s address to the League?” He then proceeds with a detailed analysis.

Paradigm Shift?

In the 1992 report, Thomas Wolf called for a “paradigm shift” in the way orchestras did business as the only possible solution to the dire future he foresaw. Dempster suggests that such a shift did not occur and explains why.

The author completes his analysis with a discussion of what has gone right for the industry over the past 10 years, and what has gone wrong. He concludes with a tantalizing question.

This essay is, indeed, technical. We are fortunate that Douglas Dempster is a talented analyst who makes the material easily comprehensible. The topic is worthy of consideration by all symphony orchestra organization participants. We encourage you to read on!

The Wolf Report and Baumol’s Curse: The Economic Health of American Symphony Orchestras in the 1990s and Beyond1

Ten years ago, in June 1992, Dr. Thomas Wolf stood before the national meeting of the American Symphony Orchestra League and delivered the bad news. America’s orchestras were in trouble, trouble with a capital

“T”—a “T” that rhymed with “D,” for deficits.

If orchestras could not learn to pursue their art and deliver music to their audiences in a fundamentally different fashion—Wolf called for a “shift of paradigms”—then the industry would continue to sink, inexorably, beneath a tide of growing deficits, aging audiences, and increasing cultural isolation and irrelevance as classical music became an elite and unaffordable cultural tradition.

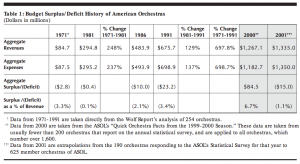

Without “changes . . . in the way orchestras do business—changes that are substantial and systemic . . .”—including significant downsizing of the core orchestra, reduction of concerts and services, consolidation of municipal orchestras into regional orchestras, a move away from performing in grand venues in city centers, and even de-emphasizing the live-concert experience— the Wolf Report projected that the industry would, by the year 2000, have sunk over $64 million into deficit2— twice the aggregate deficit of orchestras in 1991.3 This “status quo” trend projected deficit spending accelerating relative to revenue growth: the report projected total industry revenues, into 2000, at just over $946 million for the industry as a whole,4 a 40 percent increase over total industry revenue of $675.7 million for 1991.

Wolf’s dire projections were based on a simple extrapolation from the five years preceding the 1990-1991 season. Yet, as the report clearly pointed out, economic conditions could change, government support could become more generous, labor negotiations could become more amicable, private giving could save the day; any number of conditions that aggravated the economics of orchestras during the 1980s could, over the short run, delay the outcomes projected by the report.

However, the report took a long, historical view of orchestra economics and argued, from sound cultural economic theory, that the trends sooner or later…

How Many? How Much? How Representative?

The American Symphony Orchestra League (League) estimates a “world” of 1,800 American orchestras. That number includes youth, student, collegiate, and community orchestras. Approximately 900 of these are members of the League. Of these, nearly one third are wholly nonprofessional orchestras. The remaining two thirds, 625 members, are, in some sense, “professional” orchestras. The League Statistical Survey categorizes these orchestras into eight “groups” by size of budgets. In a typical year, approximately 200 of these professional orchestras respond to the League’s statistical survey. The statistical survey for 2000-2001, includes responses from 190 orchestras, whose expenses range from as little as $26,000 for the season to as much as $70 million. The League, in monitoring the economic status of the industry, must extrapolate from self-selecting respondents to the entire range of professional orchestras.

An overwhelming percentage of the measurable economic activity among professional orchestras is attributable to a comparatively small number of the largest-budget orchestras: approximately 70 percent of all expenditures and revenues in the industry are generated by the largest 55 orchestras—fewer than 10 percent of all professional orchestras. Because of the lopsided nature of the data, most discussions of the economic health of the industry focus on these top 10 percent of orchestras. But it would be a huge misrepresentation to equate this top 10 percent with the orchestral culture of the United States. These 55 orchestras, though economic heavyweights, produce only about one third of the annual professional orchestral concerts in the United States. Obviously, were we to add in the concerts of nonprofessional orchestras, the overwhelming majority of all U.S. symphonic concerts would occur outside the scope of these economic analyses.1

1 Membership data provided by League Research Department.

…would lead to the same place: artistic expenses, inexorably, outpacing earnings; private giving less and less capable of closing the widening gap between earnings and expenses; and public support for the arts continuing to wane. The Wolf Report was uncertain on the question of “when,” but was utterly unequivocal on the question of “whether” the industry faced this crisis. Without a “paradigm shift” in the way that orchestras were doing business, growing deficits would erode the viability of the industry and threaten the culture of orchestral performance.

The Wolf Report was a thorough economic analysis that was also very sensitive to the realities of the orchestral culture. It was based on the American Symphony Orchestra League Statistical Survey, the best and most extensive data available on any one segment of the performing arts world. The economic theory underlying the analysis, William Baumol and William Bowen’s seminal work5 on the economics of the performing arts, is accepted wisdom for the field. The lead researcher, Thomas Wolf, took an unbiased view of the orchestral industry and was motivated by a lifelong passion for the legacy and future of the American symphony orchestra.

It’s all the more puzzling, looking back 10 years later, to realize that none of the report’s simple projections was even close to being right. The financial health of American orchestras improved steadily throughout the 1990s. For the 1999-2000 season, the League reported total revenues of $1.267 billion, a $591 million increase over aggregate revenues in the 1990-1991 season, as reported in the Wolf Report. More importantly, the industry enjoyed this expansion and prosperity while restraining its appetite: the League reported an industrywide $84.5 million surplus, above expenses that grew at a comparatively slower pace than revenues.6

Of course, growing prosperity and restraint have been balanced by comparatively bad seasons in 2000-2001 and 2001-2002, as the economy entered and worked through a recession. The coming season, 2002-2003, for various reasons that will be discussed later, is likely to be as, or even more, challenging than the past two seasons. All this needs to be considered in reflecting back on the Wolf Report and looking forward to the future economics of the industry.

How was the crisis averted? Did the orchestral industry shift its paradigm? If not, how did it avoid the sobering forecast of the Wolf Report? Did the booming 1990s simply forestall the inevitable outcomes predicted by Wolf? And will the current downturn in the economy unleash the crisis once again? Alternatively, how could so thoughtful an analysis as the Wolf Report seem to get it so wrong?

History of the Wolf Report

In 1990, The Wolf Organization, Inc. was contracted by the League to do an analysis of the economic status of the symphony orchestra industry. Everyone knew that the analysis was not likely to bring good news: orchestras had struggled through the 1980s with many labor disputes and financial challenges. By design, the analysis by Wolf and his associates was intended as “Phase I” of a three- phase reform program instigated and led by the American Symphony Orchestra League. The Wolf Organization’s report—which is formally titled “The Financial Condition of Symphony Orchestras,” but has been known since its completion as the “Wolf Report”—was to be followed by a more forward-thinking investigation of ways that the industry might reform itself. This second phase was completed and the results were published as Americanizing the American Orchestra.7 These first two phases were intended to provide the research and

blueprint needed for a third and final phase that would lead to sweeping reforms supported by external funding.

The strategy never came to fruition. The Wolf Report and the Americanizing document touched off such controversy that no major, national funding initiative grew out of the effort. A feel for this controversy can be found in reactions to the Wolf Report. Some, like Deborah Borda, then managing director of the New York Philharmonic, read the Wolf Report as a call to arms for the industry:

Therein lies the first and crucial step. The “Holy Deadlock” that exists today between most boards, orchestras, and staffs must be broken. If we can’t find a more productive way of working together toward genuine change, we will eventually drive off that cliff. For any of the valid issues and questions posed by Wolf to be addressed so as to create meaningful change in our industry, we must begin to consider some fundamental changes in our governance functions. We must create a new protocol.8

Older hands like Peter Pastreich, then executive director of the San Francisco Symphony, took the unflappable view that crises come and go; that orchestras need to respond, but not panic:

We do have a critical financial problem. The orchestras are spending more than they are taking in, and if they don’t stop doing that soon there will be some disrupted seasons and lowered living standards for musicians and administrators. But the situation is not critical, not serious, and music will survive. What we don’t need to do is to allow the financial problems which have developed from over optimism, poor management, and admirable generosity to drive us to “solutions” which are worse than the problem. What we do need to do is balance our budgets: take in more money and spend less. And continue to be an innovative, living force in the American cultural scene.9

The reliably cranky critic Samuel Lipman had this to say in the New Criterion about the League’s efforts through the Wolf Report and Americanizing the American Orchestra: “[S]o great is this disgrace that it provides ample grounds for the dissolution of the American Symphony Orchestra League. The League clearly does not have in mind either the interests of our beloved symphony orchestras and their audiences or the future of great music.”10

Though the initiative represented by the Wolf Report and by Americanizing the American Orchestra never led to a third, funding phase of reforms, it would be a mistake to underestimate the influence of the reports. Both reports were broadly disseminated and digested. They set off a widespread debate and, without a doubt, had an enormous influence on the expectations of managers, musicians, board members, funders, training programs, and others with a stake in the orchestral culture and business of the country.

The Wolf Analysis

The Wolf Report made a simple argument based on excellent data and sound economic theory. Professional orchestras had managed to cover approximately 40 percent of their operating expenses out of earned income, including ticket sales, fees for performances, and recording income. The balance of operating expenses were covered by private and foundation gifts, public subsidies, and endowment income.11 However, the Wolf Report’s analysis showed an increasing earned “income gap” over a 20-year period. In 1971, earned income provided 44 percent of the cost of providing 13,000 concerts, leaving an income gap, per audience member, of $2.78 that had to be raised from other sources. By 1981, earned income had sunk to 37 percent of expenses for 20,100 performances. Combined with revenue and expenses that had nearly tripled in 10 years, this left a per-audience-member income gap of $7.95 that had to be raised. In 1991, earned income had improved as a percentage of expenses, coming in at 39 percent, yet revenue and expenses, again, more than doubled over that 10-year period, creating a per-audience-member gap of $15.91 to be covered by unearned revenue.12

On the face of it, this trend would seem to be reason for celebration: the numbers revealed a rapidly growing nonprofit performing arts industry with a record of being able to generate additional revenues to fuel growth. Beneath the surface, however, the Wolf Report saw that the industry was dependent on revenue growth, both earned and unearned, that would somehow have to keep pace with very large, annual cost increases. The report was soberingly pessimistic about those traditional revenue sources being able to continue the same rapid growth that was affecting orchestras on the expense side.

Government spending on the performing arts showed only faint signs, in 1991, of any growth. The “Culture Wars” had so politicized public support for the arts that there was, at that time, every reason to think that the public sector might get out of arts sponsorship altogether.

In spite of spectacular growth in general philanthropy through the 1970s and 1980s, the report worried about the trend toward symphony orchestras and the performing arts generally receiving a shrinking share of that overall giving. If philanthropy overall were ever to flatten or decline, orchestras could expect declining revenues from individuals, foundations, and corporations.13

Finally, the report foresaw few prospects for ticket prices, expanded services, or endowment growth to close the growing earning gap.

Why not assume that orchestras, like other businesses facing diminishing income, could control expenses? Why, in 1991, did the Wolf Report’s analysis not project that orchestras would and could react to growing deficits and the growing income gap through constraining costs? The answer to this is complicated.

In the Wolf Report’s analysis, the growing gap between earned income and expenses was a trend being driven largely by artistic expenses. Why, exactly, the report came to this conclusion is puzzling; the supporting data are, at best, ambiguous. The report admitted that “. . . the real growth of artistic personnel expenses over the past five years [i.e., 1986-1991] was about the same for expenses overall.”14 The report went on to say, however, that:

The figures provided represent aggregate totals for the industry and there are many individual orchestras in which artistic personnel expenses did drive overall expense increases. This was particularly true for larger orchestras where artistic personnel expenses kept significantly ahead of inflation. . . . The largest orchestras (those with budgets in excess of $8.5 million) saw real growth in average weekly salaries of 6.2% between 1986 and 1991 after adjusting for inflation.15

Given that fewer than 10 percent of member orchestras in the League make up more than 70 percent of all economic activity in the industry, a highly inflationary trend in the compensation of musicians in top orchestras was reason for genuine concern.

The report also speculated that the increasing cost of other expenses such as marketing and fundraising, though they kept pace with artistic expenses, were also, in effect, artistic costs. “The decision on how many concerts to play seems not to be established by audience demand, but instead by the collective bargaining with musicians.”16 Better compensation for musicians has meant extended seasons and more services, which have in turn required expanded marketing, more savvy programming, civic partnerships, and greater fundraising to create or find audience demand or, simply, to stimulate more giving. The picture painted by the report is of an industry expanding under pressure from the supply side—musician and union insistence on expanded contracts—rather than being drawn into growth by expanding audience demand.

What’s puzzling about this analysis is that even through 1991, the industry had done pretty well at managing a very rapid…

Comparing Apples and More Apples

Comparing figures on the orchestral industry is tricky business. The American Symphony Orchestra League Statistical Survey collects financial data for orchestras grouped by size of expenditure. Averages, medians, and ranges in this survey are a consequence of which orchestras choose to respond. Large, well-staffed orchestras are more likely to report, other things being equal, than smaller orchestras or orchestras facing financial hardships. Any orchestra with good news is more likely to report than an orchestra with bad news. Response rates in the statistical survey are high for high-budget orchestras—virtually 100 percent for Group 1 orchestras— and diminish for smaller-budget orchestras. Fewer than 15 percent of the lowest-budget professional orchestras responded to the League’s statistical survey for 2000-2001.

The Wolf Report, which aggregated data from 20 years’ worth of surveys, included 254 professional orchestras, including the largest orchestras, but avoided the dicey business of generalizing to a larger population. The League does some aggregate financial reporting on the overall industry in its “Quick Orchestra Facts,” but these aggregate figures are based either on samples different from those selected by the Wolf Report or on “extrapolations” from those samples. The author’s review of the 2000- 2001 statistical survey included 190 participating orchestras with extrapolations being made to a population of approximately 625.

In sum, comparing aggregate numbers that have been derived by different methods, from different surveys, with different groups of self- selecting, respondent orchestras is inherently error-prone. Nevertheless, by exercising caution, some broad tendencies and trends are conspicuous enough.

…expansion as measured by aggregate budgets, number of orchestras, number of concerts, and the aggregate size of the audience. Even deficits, which grew during the 1980s, were kept comfortably in scale with the expansion of revenues.

To be sure, aggregate deficits grew rapidly between 1986 and 1991, calling for some strong fiscal medicine. But the spectacular expansion of the professional orchestral industry in the United States dates back at least to the mid-1960s. In fact, the Wolf Report’s own analysis shows aggregate deficits for the industry— taken as a percentage of aggregate revenues—growing insignificantly over that 20-year period (see Table 1). Deficits actually declined between 1971 and 1981, the industry’s period of most rapid expansion, proving that orchestras were capable, at least during that period, of rapidly generating revenues to match the rapidly increasing costs of expansion.

Baumol’s Curse

Part of the reason for interpreting these industry trends in a most pessimistic fashion has to be found outside the data themselves. William Baumol and William Bowen published their classic analysis of the economics of the performing arts in 1966.17 Among many observations, their most important insight was to explain a feature of the economics of performing arts organizations that they referred to as the “income gap,” but which has since come to be called “the cost disease,” “productivity lag,” or sometimes just “Baumol’s Curse.” The Curse foresees that “performing organizations typically operate under constant financial strain—that their costs almost always exceed their earned income,”18 and that “rising costs will beset the performing arts organization with absolute inevitability.”19

While Baumol and Bowen’s explanation is elaborate, the underlying idea is simple enough. Orchestral musicians have supremely specialized talents that have been developed, typically, over a lifetime of training. Nonetheless, as Baumol and Bowen observe, over time, orchestras draw from the same talent pool as universities, hospitals, software developers, automobile manu- facturers, or the mining industry, for that matter. Some professions are more remunerative than others, but Baumol and Bowen’s insight was that the cost of talent in any one of these industries is affected by the comparative cost of talent in other industries. Electrical engineers don’t, of course, compete with bass players in orchestral auditions. But in the long run of an economy, the orchestral industry competes with other industries in attracting talented, young people who have a choice of professions.

Some sectors of an economy, especially manufacturing industries, are able to achieve great advances in worker productivity through technological innovation. Greater productivity, to an economist, is simply more units of output, whether that’s goods or services, per unit of labor input. Obviously, industries that achieve greater productivity per labor unit are able to generate more income for some fixed amount of labor. That greater income affords the opportunity to raise wage or compensation rates in a competitive labor market. Increasing compensation rates in one industry have, then, an indirect effect on the compensation rates in other industries—whether or not those industries have been able to achieve comparable gains in productivity. Industries that are not able to improve the comparative productivity of their talent pools are faced, as a result, either with a deterioration of the talent attracted to the industry or with the need to increase compensation rates without offsetting gains in earned income. Whence the “income gap.”

Technological Innovations

Radio, the LP, CDs, and the Internet all stimulated the audience and market for classical music. As technological innovations, they also presented a gigantic potential for gains in economic productivity for orchestras. A large concert hall can accommodate a few thousand patrons, but a radio broadcast or CD can reach tens of thousands or even millions. Alas, you can’t put “potential” in the bank. Orchestras, notoriously, have had a terrible time realizing any direct income from electronic media. There may be some consolation in knowing that the same is true for the overwhelming percentage of all commercial recordings: few break even regardless of musical style or format, even without the huge overhead costs of recording an orchestra. However, for many professional musicians, electronic distribution of their work is more nearly a marketing cost that enhances concert attendance and ticket prices. Viewed as such, these technological innovations may greatly enhance the productivity and perceived value of an orchestra.

Baumol and Bowen considered all “service industries,” (e.g., education and food preparation, as well as the performing arts) as opposed to manufacturing, to be vulnerable to the Curse.20 (More recently, Baumol has called these the “stagnant services.”21) They single out the performing arts as the very best example of a stagnant service industry that benefited very little, in terms of productivity, from technological innovations. A string quartet still requires four musicians a fixed amount of time to perform, regardless of 250 years of technological innovation since the genre became well defined.

So, in sum, the cost of talent rises “inevitably” in a growing economy, yet the unit productivity of performers does not. Ergo, the cost of presenting a performance to an audience inevitably outstrips the earning potential of that performance. Trouble with a capital “T.”

Now this is, of course, a vastly oversimplified account that should, properly, raise all sorts of questions and challenges. Radio, various generations of recording media and playback devices, and more lately, the virtually mediumless distribution of music over the Internet have created enormous potential for increased productivity in various entertainment industries, including orchestral music. Larger concert halls and summer festival venues are, in effect, technological innovations that increase the

audience capacity for a concert or an orchestra. Educational and other programming formats that tend to require less rehearsal preparation are also ways of increasing the productivity of an orchestra.

Be that as it may, whatever innovations may marginally improve the productivity of orchestras, Baumol and Bowen argued that, as an industry, the performing arts were at a technological disadvantage relative to other industries, and that this was enough to ensure that the performing arts would struggle with an ever-growing gap between earned income and expenses.

In many ways, the Wolf Report was simply a case analysis of the orchestral industry viewed through the prism of Baumol and Bowen’s theory of the economics of the performing arts, and it confirmed, 25 years later, their pessimistic forecast for the performing arts.

Ten Years Later

Where does the orchestra industry find itself 10 years after Thomas Wolf’s address to the League? For the 1999-2000 season—the season for which the Wolf Report projected a $64 million deficit—the industry posted, according to the League, an estimated $84.5 million surplus (extrapolated from 203 responding orchestras to approximately 1,800 orchestras). Total revenues and expenses for the season were, respectively, $1.267 billion and $1.183 billion.22 The Wolf Report projected 2000 revenues at $946.5 million and expenses at $1.01 billion, greatly underestimating the prospects for growth in the industry.

“Extrapolations” and “self-selecting respondent orchestras” are likely to cause suspicion among statisticians. Deficit trends, perhaps in different sectors of the industry, may be hidden in industrywide, aggregated averages. However, when the League controls for that kind of error, the outcomes are equally impressive. When the League looked at a constant sample of reporting orchestras over the nine years between the 1990-1991 and the 1999-2000 seasons, there were 109 orchestras that, in aggregate, produced an overall surplus in 1999-2000 of $12 million. That same group of orchestras, in 1990-1991, reported an overall deficit of $26.7 million.23

The Wolf Report’s surplus/deficit projections were clearly mistaken. Given the controversy that swirled around the report, that’s the outcome that will matter most to many reading this article. However, it could easily distract us from a more important, if less salient, prediction: the report was remarkably accurate in predicting the scale of growth that the industry enjoyed through the decade of the 1990s. The Wolf Report calculated that industry revenues and expenses, in nominal dollars, grew nearly 800 percent in the 20 years between 1971 and 1991, a period of spectacular growth. By contrast, between 1991 and 2000, in nominal, non- inflation-adjusted dollars, the industry grew only 90 percent over a nine-year period, a healthy but much slower rate of growth than in previous decades. The Wolf Report clearly anticipated the trend toward deceleratinggrowth, which may, in the end, prove far more significant to the industry than its periodic slumps into modest deficits.

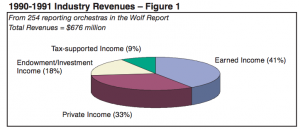

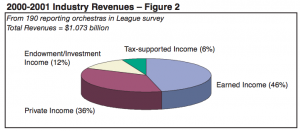

The 30-year trend toward growth and prosperity seemed to continue through the 1990s, with expenses growing rapidly, and revenue, in the form of earned and unearned income, keeping pace. Over this period, according to the League,24 income from ticket sales (i.e., part of overall earned income) rose more than 50 percent. By 1999-2000, individual giving had doubled the rate of a decade earlier, growing from $90.5 million to $188.5 million. Business and foundation giving improved very significantly, though not at the huge rate of individual giving. Public subsidies, not surprisingly, seem to have shrunk for orchestras during the 1990s from the approximate range of 9 percent of total revenues reported by the Wolf Report for the 1990-1991 season to approximately 7 percent for the 2000-2001 season (see Figures 1 and 2). But even this has to be understood against the background of orchestra budgets having nearly doubled through the decade. Though public subsidies shrank as a percentage of budgets, total public funding for orchestras grew very substantially through the 1990s.

This growth and prosperity, so at odds with the forecast of the Wolf Report, might be chalked up to a booming economy throughout the 1990s, which surged, as a matter of good luck for all, right through the season of 1999-2000, the arbitrary year chosen for the Wolf Report’s projections. We might wonder, naturally enough, whether the underlying reality of a growing income gap was just waiting to wreak its “inexorable” deficit havoc once the economy leveled off or declined.

There’s no need to speculate about this. The 1980s ended with a slowing economy that entered a genuine recession in 1990 and 1991, which influenced, in part, the projections of the Wolf Report. The economy of the 1990s behaved very similarly, surging into the second half of the decade and cycling, we now know, into a recession in the first three quarters of 2001.25 In fact, the last two quarters of 2000 saw a dramatically slowing economy, even before entering the 2001 recession. Consequently, this weak economy fell, without warning, on the entirety of the 2000-2001 season and fiscal year, making it the most challenging season in the previous 10 years.

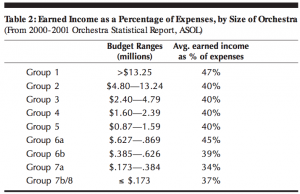

How did orchestras fare? In spite of bad news from Toronto, St. Louis, Baton Rouge, San Jose, and most alarmingly, at the fiscal gold-standard for the industry, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, one would have to conclude that the orchestral industry as a whole managed very well. All together, orchestras did suffer an aggregate deficit for the 2000-2001 season, but they did not come close to the 7 percent deficit (i.e., expenses in excess of revenues) projected by the Wolf Report in 1992. The 190 participating orchestras in the League’s 2000-2001 statistical survey reported a cumulative deficit of $17.5 million, only 1.6 percent more in expenditures than revenue. Most impressively, of a total $1.083 billion in revenues, those 190 orchestras earned $488.5 million through concert income and other services.26 That’s fully 45 percent of total revenue from earned income, a significant improvement over the 41 percent earned income for the 254 orchestras represented in the Wolf Report (see Figures 1 and 2). The largest 25 orchestras, which constitute 71 percent of all the measured economic activity in the industry, earned 47 percent of their expenses during the 2000-2001 season.

That’s not quite the same thing as increasing productivity, in the strict sense of the economist, but it is a clear indication that orchestras are resisting a fate projected by the Wolf Report and foretold by Baumol’s Curse. Contrary to the warnings of the recent Rand report on the performing arts,27 the author’s analysis of earned income among orchestras responding to the 2000-2001 statistical survey showed no special disadvantage for mid-sized orchestras. If anything, it’s the smaller orchestras that seem least able to cover their expenses through earned income.

The news is not all good, of course. Orchestras are performing many more concerts than ever in order to reach the same number of audience members. According to League estimates, total audience attendance for orchestra concerts has grown little, if at all, over the last several years. By contrast, the number of concerts performed, again according to League estimates, has grown and continues to grow by leaps: by as much as 23 percent since the 1995-1996 season and by as much as 45 percent since 1990-1991.28

On the face of it, that represents an extraordinary loss of productivity that would have to be offset by rapidly increasing ticket prices or other sources of income. Indeed, average ticket prices increased 70 percent between 1985 and 1995.29 The truth, however, may not be so alarming: the real measure of productivity is in the number of performance services orchestras require to generate a fixed number of concerts or ticket sales. Performances that require less rehearsal time, or programs that can be frequently repeated, allow an orchestra to increase the number of concert events without increasing underlying costs. Nonetheless, it’s certainly not a good thing that many more concerts are required to reach the same size audience, especially not if that comes only with less variety in programming, with fewer rehearsals, and at a higher cost to the audience.

The decline in public subsidies for orchestras is worrisome, but no surprise (Figures 1 and 2). Between 1991 and 2001, tax-supported revenues for orchestras shrank from 9 percent to 6 percent of total revenues for the industry. This was in spite of the fact that total government appropriations for the arts grew steadily through the decade of the 1990s. However, as has been well understood for some time, larger appropriations are being divided among more and more constituencies through the very politicized process of public arts funding. That orchestras have even held onto such a large share of these subsidies (even while that share shrinks as a percentage of rapidly growing budgets in the industry) is a political and economic success for the industry.

A much greater concern—perhaps the single greatest concern—is that endowment and investment income has declined relative to other sources of revenue (Figures 1 and 2). Between 1991 and 2001, endowment and investment income for all orchestras declined from 18 percent of total revenues to 12 percent, fully a one-third reduction. The author was not able to obtain data on orchestra endowments. However, the fact that endowment income did not grow at the pace of earned income or private giving suggests that too little revenue has been invested for future income, even when private sponsorship was at all-time highs. The industry has to be concerned that orchestras may have been balancing budgets, even during a boom economy, by drawing too aggressively on their endowments. Now, as the economy recovers from a recession, with the threat of decreased public and private support, orchestras may not have the endowment resources they should in order to cushion against imminent declines from these other sources of income.

Having weathered the 2000-2001 recession, the orchestral industry, though having the advantage of being on guard, is likely to face worse in the next two seasons. The 2001-2002 season was, of course, rocked by the disaster of September 11. In the end, however, the economic effects of September 11 will prove less significant than many other factors. As this article is being written in the summer of 2002, personal income has recovered very rapidly after the 2001 recession. Consumer spending remains strong and consumer confidence is recovering, with vacillations, from a hard fall after September 11 and a recession. Inflation is modest. New claims for unemployment are going down. Manufacturing inventories are climbing again. That’s the good news.

The bad news is that much of the unearned income raised by most orchestras is threatened from an equities market that has lost as much as one-third of its value over the last 18 months. Individual, foundation, and corporate contributions and sponsorships, influenced by the value of these equities, will, with certainty, go down or take longer to be realized. Orchestra endowments, which are not as large as they should be after a decade of strong economic growth, will have grown little or will have even shrunk over the last year. Unless orchestras have a very conservative investment and endowment- spending discipline, short-term loss of income from endowments will be very painful.

State and local tax revenues, a very significant part of all public subsidies for orchestras, have been stagnant since 2000.30 For fiscal year 2002, for the first time in six years, total appropriations to state arts agencies decreased from the previous year, from $446.8 million

in 2001 to $411.4 million in 2002.31 The industry as a whole, then, can expect reduced tax-supported income in 2002-2003. (The bad news about reduced overall public funding for the arts has to be balanced against the good news that a majority of states have actually increased appropriations for the arts, and that the National Endowment for the Arts has seen the single largest increase in its appropriation in more than 15 years, an initiative that came out of the U.S. House of Representatives.)

Many orchestras are struggling to contain deficits incurred in 2001-2002. Early anecdotal indications are not encouraging. However, costs and deficits are much more containable than they were 20 years ago, just by virtue of the much greater size and diversity of many orchestral programs and operations. Though painful and regrettable, orchestras can make up large savings by reducing administrative staffs, cutting noncore programs such as tours or recording projects, controlling operational overhead, and scaling down marketing costs. All of this can be done before cutting into the core artistic and/or educational mission of the orchestra. Admittedly, these can be drastic remedies with a potential for setting off a spiraling decline; the perils of cost reduction have to be weighed prudently against incurring deficits and carrying debt burdens. But the important point is that an economic downturn for the industry needn’t trigger a trend toward the uncontrollable income gaps and deficit spending predicted by the Wolf Report and Baumol and Bowen’s economic theory of the performing arts.

Did the Paradigm Shift?

To avoid, or forestall, the fulfillment of Baumol’s Curse, Thomas Wolf, in 1992, called for a “paradigm shift” in the way orchestras did business. Did that paradigm shift occur? Is that why orchestras enjoyed nearly 10 years of growth and prosperity and seem to be weathering an economic recession in comparatively good health? Did the Wolf Report help avert the Curse?

The most obvious and straightforward answer is a simple “no,” nothing like the called-for paradigm shift happened. In fact, the last decade seems to have been business as usual, just more so. The size of full-time “core” orchestras has not shrunk noticeably. Greater productivity has not been achieved, as Wolf urged in 1992, by shrinking the number of concerts or consolidating municipal orchestras into regional orchestras. In fact, the number of concerts presented has grown nearly 50 percent over 10 years, rather than shrinking, even though total audience participation has been stagnant. In Tokyo, Japan, two of the city’s nine major professional orchestras, the Japan Shinsei Symphony Orchestra and the Tokyo Philharmonic, did merge in 1999. The only comparable merger in the United States is the recent decision to combine the Utah Symphony and the Utah Opera.

Perhaps most surprising, the grand, centrally located, urban concert halls— shining palaces for the performing arts—have not become the victims of suburban sprawl, as suggested by Wolf and others. If anything, constructing grand concert venues has become more crucial to the marketing strategies of orchestras than ever before. Indeed, for many cities struggling to remedy the loss of business and retail anchors in the urban core, arts and entertainment, including grand concert halls for classical music, have provided an answer. Heidi Waleson, in a recent article on the subject in Symphony magazine, concludes that “. . . after decades of moribund development and suburban flight, downtown is hot again— and concert halls are a prime component of the turnaround.”32 A 1993 study by the Association of Performing Arts Presenters showed that fully one-third of all performing arts venues in the United States had been built between 1980 and 1993, with the pace of construction apparently accelerating in the 1990s.33

New, major concert halls, often in multipurpose performing arts centers, have been recently completed or are in various phases of planning and construction in Newark, Seattle, Philadelphia, Fort Worth, Atlanta, Los Angeles, Detroit, Kansas City, Austin, Nashville, and Denver. Many other major concert halls across the country, such as Avery Fisher Hall in New York City, are being planned for major renovations. The early success of the Philadelphia Orchestra in Verizon Hall, part of the recently completed $265 million Kimmel Center, will not be lost on other orchestras and their communities. The Philadelphia Orchestra reported, as a result of resold subscription tickets, 102 percent attendance for concerts presented in the new Verizon Hall34 (concerts overall for the season reached 99 percent of capacity), in spite of the fact that top price for single tickets in 2001-2002 was $110 and next season will go to $130.35 As early as June 2002, the orchestra reported a 78 percent subscriber renewal rate for the 2002-2003 season.

Orchestras have also been largely frustrated in their efforts to reach larger audiences through electronic media, one of the imperatives of Wolf’s new paradigm. Very few orchestras can any longer attract recording contracts that satisfy union pay scales. The recording industry, which is seeing shrinking profit margins on the few recordings that can get beyond a break-even point, is more reluctant than ever to subsidize high-cost recording projects with symphony orchestras. The core symphonic repertoire, which makes up the backbone of classical recording sales, has been exhaustively recorded by orchestras around the world, overwhelming record buyers’ appetites for collecting.

It’s worth pointing out as well that the quality of carefully performed and engineered recordings is generally so high, that for the vast majority of the record- buying public, there’s an indiscernible difference in interpretation and quality of performance between one performance of Ein Heldenleben and the 72 other recordings currently available through the Amazon.com listing. For the vast majority of the listening public, there’s insufficient product differentiation in orchestral recordings to justify the abundance of choices.

There’s little doubt that the total “extended” audience for classical music— and by that I mean the radio-listening, CD-buying consumer, as opposed to that special class of listener, the live-concert attendee—has grown enormously as a result of electronic access to a diverse range of high quality, “classical” music. That vastly increased audience is a pool of at least minimally literate listeners: listeners who are familiar with Mozart, Beethoven, and Tchaikovsky. While the aficionado may denigrate the “casual” listener, at least the casual listener hears differences and similarities in these compositional and performance styles, though he or she may have trouble expressing these observations. More importantly, even the casual listener will have, however naïve, preferences for music within the tradition—“I like Beethoven and Leonard Bernstein, but you can keep that ‘modern’ stuff.” These naïve preferences are the stuff that more sophisticated musical appreciation—and perhaps even an appetite for live-concert experiences—are made of. Cheap, abundant, electronic access to high-quality classical music has been a huge stimulus to the culture and industry of classical music. Orchestras are, in spite of the frustrations of turning a buck on classical recordings, clearly enjoying the economic benefits of that enlarged audience base. To that extent anyway, the industry has “shifted” in the direction pointed out in the Wolf Report. But marketing and performing through radio and recordings hardly seems an innovation for the industry.

Thomas Wolf proposed other important aspects of the industry paradigm shift:

◆ greater ethnic diversity among orchestra players, management, and board members;

◆ more innovative programming strategies;

◆ educational programming designed around more thoughtful pedagogical assumptions;

◆ the need for orchestras to pursue more creative community partnerships; and

◆ the importance of greater player involvement in orchestral governance and strategic planning.

Progress toward these goals has been mixed. The ethnic diversity among orchestral musicians, managers, and board members seems to have changed little if at all over the last 10 years, in spite of various efforts among training programs and orchestras. With the sponsorship of organizations such as the Knight Foundation, programming strategies, at least among the prosperous organizations that can afford to experiment with their audience bases, have become more inventive. Orchestras are investing much more in educational programming. They are reforging strong community partnerships that have, with little doubt, been key to the prosperity of many. And orchestral governance and organizational culture are subjects of broad discussion and occasional innovation.

Progress is progress, even if modest, and as such, worthy of recognition and applause. But these modest advances hardly seem so sweeping as to constitute a “paradigm shift” in the industry, hardly seem a change in the fundamental way of going about the orchestral business, and hardly seem an explanation of how the industry averted the grim projections of the 1991 Wolf Report. That’s the simple answer, anyway.

What Went Right? What’s Gone Wrong?

The more complicated answer is that the Wolf Report, and the subsequent Americanizing report, very likely did much to frighten the industry into fiscal sobriety. Looking back to the American Symphony Orchestra League’s national meeting of 1992 and the exchange between Thomas Wolf and various orchestra representatives, Peter Pastreich’s veteran advice seems to have called it closer than anyone. The industry was facing a challenge and not a crisis; orchestras were spending more than they were taking in. In Pastreich’s sober judgment, they would all have to cut that out. Not a paradigm shift, but shrewder management; more aggressive marketing and fundraising; program innovations; cost controls; and more efficiency where efficiencies were possible. More and better concerts; better programming; better business.

The most important and remarkable fact is that orchestras have, somehow, done what accepted theory in cultural economics seems to say they should not be able to do. Stagnant service industries, Baumol warns us,

. . . suffer from a rise in their costs that is terrifyingly rapid and frighteningly persistent . . . as financial stringency becomes more pressing, it is understandable that spending on these services is cut back or, at most, increased by amounts barely sufficient to stay abreast of the overall price inflation in the economy. But since the costs of the stagnant services are condemned to rise, persistently and cumulatively, with greater rapidity than the rate of inflation of the economy, the consequence is that the supply of these services tends to fall in quantity and quality.36

Orchestras have, indeed, seen nearly a doubling of average annual expenditures over the past 10 years. That would be terrifying but for the fact that the percentage of total expenditures covered by earned income has actually increased over that period. Baumol and Bowen’s theory predicted that the earned- to-unearned income ratio would inevitably decrease as the income gap steadily widened.

The theory would also lead us to expect that the expense of artistic personnel would steadily grow in comparison with other aspects of an orchestral operation, such as financial management, marketing, stage operations, fundraising, and education, all of which can benefit from technological efficiencies. But that hasn’t happened either. The cost of artistic personnel in orchestras has remained stable at 51 percent of total expenditures for many years. In fact, the largest and most prestigious orchestras (League Group 1 Orchestras, with average budgets of $30 million)—those in which the cost of artistic personnel is not only the highest but also the most critical to the orchestras’ success—spent, on average, only 48.7 percent of total expenses on artistic personnel in 2000-2001.37

In the face of such facts, the theory would predict a deterioration in the quality of the talent and concerts, or in the quantity of performances offered by the industry, as a result of the industry’s constraining the cost of artistic labor in a competitive labor market. But the opposite seems to be true.

Clearly, there’s something wrong with the underlying theory. Or, more likely, there’s something wrong with the assumption that the orchestral industry is a “stagnant service” industry. In fact, if we take the theory seriously, it would be something of an economic enigma that there is anything like a 150-year-old orchestral industry at all. One would expect the business to have wasted away long ago due to the long-term debilitating effects of the cost disease.

While the performance of a Beethoven symphony takes the same number of musicians the same number of minutes (within a few musicians and minutes, anyway) to perform as it did 200 years ago, greater productivity may have been achieved in other ways. For instance, orchestras may be finding ways to decrease the rehearsal time required to prepare and stage a concert. Or the absurdly large number of American music students (i.e., something on the order of 8,000 music students graduate from accredited music programs each year) being trained for the profession of orchestral performance, and trained at higher and higher levels, is infusing orchestras with extremely high-caliber musicians. This bears more careful study.

Or perhaps the theory is neither ill-conceived nor mistaken in its assumption about the “stagnancy” of the orchestral industry. After all, being a “stagnant” service industry means only that an industry cannot achieve gains in productivity comparable to other industries competing for talented employees. There’s little question that the orchestral industry is “stagnant” relative to computer manufacturing or pharmaceuticals, and even in comparison with other enter- tainment industries, such as spectator sports, which have achieved enormous productivity—albeit one-time gains—through the mass media.

The real problem may not be that Baumol and Bowen’s theory is mistaken in some fundamental way. Indeed, their work made a compelling argument for the performing arts not, as a rule, ever being able to flourish without subsidies that exceeded their earning power. Indeed, without that understanding, there would be no orchestral industry in this country to speak of.

In the end, the problem with the theory—and with the Wolf Report that applied the theory—is not that it is mistaken so much as that it explains so little, as a theory, about the economics of the orchestral industry and other performing arts. The orchestral industry is “stagnant.” It does suffer from the cost disease. In spite of that, it has prospered and grown, steadily, over a 40-year period. Few orchestras of any importance have dissolved over that period, and those that have, such as the San Diego Symphony, were, in short order, reorganized and revived. Rather than a theory that explains how vulnerable and nonviable these organizations are, we need to understand why they are so durable and resilient— in spite of the validity of Baumol and Bowen’s theory. In spite of Baumol’s Curse, most orchestras have been able to close the income gap through unearned income that has managed, somehow, to keep pace. But “somehow” explains little. We need to better understand how these nonprofit, high-culture performing arts organizations have cultivated such generous, and growing, private and public subsidies and what the long-term prospects are for this trend.

Most important, orchestras have managed to keep the income gap, as a percentage of total revenue, from growing over the last 10 years. In fact, the industry has gained some ground, improving the ratio of earned to unearned income by better than 10 percent over the period. There are several reasons for this, but one of the clearest and most significant has been the ability to pass along highly inflationary costs to the audience through greatly increased ticket prices. The performing arts, like education and health care, have grown not through greater productivity, but through greater perceived value. In each case, consumers have proved a willingness and the wherewithal to spend a larger and larger portion of their incomes on these “stagnant services.”