The Composition of Intellectual Capital

The Composition of Intellectual Capital1

Dimensions of human capital and structural capital were identified in the last article (“The Typology of Intellectual Capital”) and provided by detail in table format. Also noted is that my overarching concern in the case study was to answer the fundamental question: How is IC used in community NPO orchestras?2 The use of IC is unique to NPOs that are shaped by behavioral attributes such as participation, motivations, and personal goals. In this article, I’ll explore how human capital and structural capital are not independent of each other but rather interrelated. IC is best understood in context of how human capital and structural capital are related and thus lead and guided rather than merely managed as a set of separate resources.

Interrelationships in Human Capital and Structural Capital

After attaining the list of human capital and structural capital types based on their specific dimensions, I then focused on determining how both are interrelated. Since the aim of the case study was to see how IC is used in the orchestras, I needed to determine the connections between Human Capital and Structural Capital. Specifically, how a musician skills are related to components of the process. With several notes from field observations, interviews served the purpose of exploring if any relationship existed between human capital and structural capital.

Since much of my field work and interview questions naturally focused on individuals enacting what they know during rehearsal, the processes and routines of the orchestra rehearsals became the point of focus for the study. Further data collection and analysis, therefore, centered on the rehearsal process coupled with what people did, what they used, their attitudes towards leadership and others, and their motivations. A couple of participant statements reveal the relatedness of human and structural capital elements during rehearsal:

“There’s a certain amount of anxiety in rehearsal, along with chaos, concentration, intensity, and sometimes a bit of exhaustion. But it’s needed to get the performance down for the audience.”

“Pandemonium. I’m distracted by sounds or if others don’t play right….but putting the concert program together by taking it apart….then putting it back together again. You need wits and attention.”

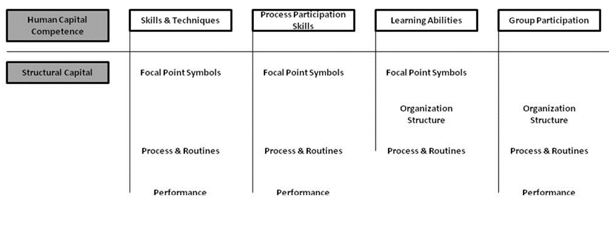

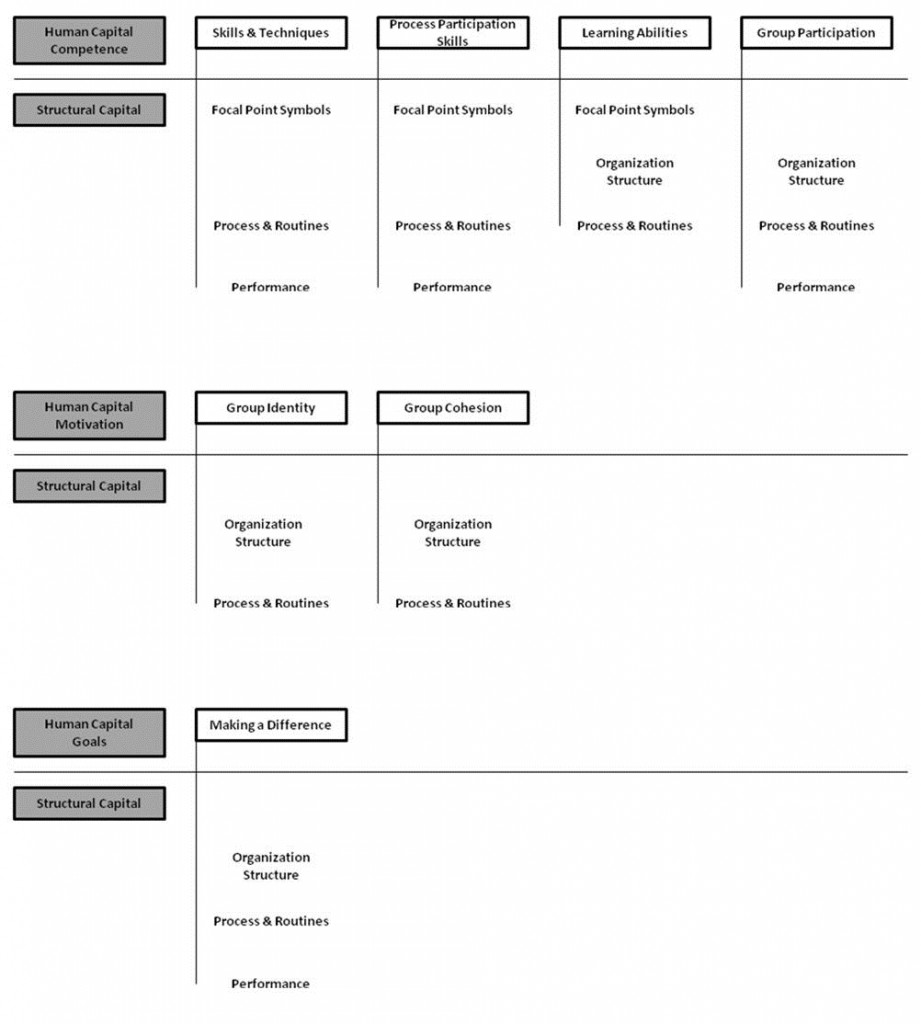

Embedded in the above statements are the rich connections between the struggles of applying skills (human capital) in the process (structural capital) of providing patrons the final product in the form of a concert. By analyzing and interpreting similar interview data via pattern matching I was able to derive some essential relationships between human capital and structural capital. Table I (end of article) exhibits the layers of interrelationships between the two capitals for community orchestras.

Dynamics of Interrelated Capitals

The following are some observations, not exhaustive, of the interrelatedness between human capital and structural capital. First, there is the concentrated interrelatedness between structural capital routines, processes, and focal points with human capital “competencies”. Musician skills and techniques are directly related to the conductor’s signals, feedback, and listening to others found in the processes of rehearsal.

“An important thing for me is giving what the conductor wants in performing the music. Not getting yelled at helps too.”

“The conductor is there to organize. By listening to him we learn. Our ears hear other sections and how we fit with them. I really use the conductor a lot, but need to focus more on his direction and not get hung up on just reading the music.”

Coordination via the conductor and established processes directly correlate with participant competencies. In addition to the conductor, musicians also listen to others in making sense of their place in the whole process. This isn’t new to musicians, but it’s an important connection to make between a person’s skill, their place in the process, and what is leading the process. The interrelatedness here is between “Group Participation” and structural capital elements of organization structure, processes & routines, and performance. As I probed deeper, participants repeatedly stated how their skill, musicianship and learning abilities hinged on the guidance and leadership of the conductor and listening to others.

“Teamwork to accomplish something is really important. Putting the music together by following the conductor is key, but hearing it with others is perfect, as opposed to practicing alone.”

“Motivations” are central to the participants’ reasons as to why they are a part of the orchestra: to make music and belong to the group. Notable in my observations and later confirmed through interviews, was the shape of conversations during rehearsal breaks. Sections primarily talked within their section and usually about music or the current rehearsal or how the orchestra sounds or how it’s important to “nail” a section down. One principle had this to say:

“We try to build a feeling of comrades. The orchestra as a whole is one big group that works together. We build one mind and a unified section in the violins. We do this by providing fingerings and bowings to the music to help the section play well. If we do that, then other parts of the orchestra can do well.”

Community orchestra volunteers participate because they enjoy making music and being part of the group. What is notable is the relationship between human capital and structural capital that point towards participants as being part of the group. This interrelatedness between the two capitals suggests the strong correlation between a person’s contributions to the orchestra, the importance of their part in the process, and their part in the performance.

“The orchestra always needs team players. A community spirit and giving back as a group feels good. As an orchestra we always need to work together. That means being prepared to rehearse too. The conductor’s image comes out as being capable if we give him and the audience a good performance. When that happens, it makes me want to be more involved.”

“The fact that we have ambition and drive and the feeling we get when we accomplish something for the public. That’s a great thing considering many people complain they are bored.”

People will continue to participate if their contribution is indeed valued. When participation is valued this increases the musician’s sense of belonging to the orchestra. Herein is the purpose of making a difference by being part of, what Peter Drucker called NPOs, “human-change agents”.

Observations and Guidelines

Some guidelines towards leading and guiding IC in community orchestras can be gleaned from the reality of how both human capital and structural capital are interrelated.

- 1. Human capital in NPOs and community orchestras requires more than mere management of a resource, it requires guidance and leadership.

- 2. Human capital (skills and competence) performs best when inspired by leaders (structural capital focal points in the processes).

- 3. Dynamics of the orchestra working together is bolstered when they begin to know each other better.

- 4. The above have a spill-over effect by increasing the motivation and reason for being volunteers in the orchestra.

- 5. Match individual talents outside of musicianship with specific needs of the orchestra and do not overload such individuals with other tasks.

IC needs to be understood in context versus discrete parts. Musician/participant skills and techniques cannot be understood as contributing to the orchestra’s purpose without:

- 1. Conductor’s competence

- 2. Orchestra’s competence

- 3. Relationships between orchestra sections

- 4. Rehearsal and other process effectiveness

NPOs constantly wrestle with the task of connecting individual talents to the processes and outcomes the NPO is to provide. What happens is that individuals are mismatched to tasks. Volunteers possess a set of limited, but strong talent set, yet are spread thin to a variety of tasks. An IC approach discourages this allocation of resources since human capital and structural capital are connected and have specific points of relatedness.

Human capital shapes and is shaped by structural capital. If you change the musician skill base to a lower level, you don’t change the conductor’s competence you change the approach the conductor takes in leading the orchestra. The mix of human capital and structural capital as a stock is dependent on the unique resource endowments and situation of each community orchestra. The key is to best leverage what is available.

Understanding how IC is interrelated is an important part of the process for NPOs and community orchestras. This interrelatedness has a network effect. That is, changes in parts of a process necessarily impact, positively or negatively, human capital dimensions like competency, motivations, and individual goals. In the final article, I will explore how human capital and structural capital are used, as resources, in the everyday work practices of a community orchestra.

Table I: Interrelationships of Human Capital and Structural Capital

- Table 1

1 Title adapted from chapter 3 of Stravinsky’s Poetics of Music, (1974); Harvard University Press.

2 This article series is adapted from my article “The composition of intellectual capital in non-profit orchestras” in the Journal of Intellectual Capital, 2010. Many modifications particularly in table content and complete findings are reflected in this article. Readers who wish to attain full detail and findings can do so in the article found in “The Journal of Intellectual Capital”.

No comments yet.

Add your comment