A MAP TO READING AND FINDING TOPICS IN HARMONY: Eight Years of Research, Studies, and Articles

For eight years, 1995-2003, the Symphony Orchestra Institute (SOI) published Harmony. As a journal, Harmony was the application of the SOI mission that focused on improving the effectiveness of orchestras as organizations both in how they operate and how they are to be a vital part of their communities. Harmony provided a rich landscape of case studies and opinions surrounding orchestras, their operations, and their place in the community. Specifically, the journal focused on: (1) a place where field case studies on orchestras were documented; (2) a central forum allowing American orchestras to read on the developments surrounding organizational effectiveness; (3) a place where those in the industry may voice their ideas or approaches to the problems orchestra organizations face.

This paper will provide a map to the key issues that emerged from the eight years of publishing Harmony. The themes outlined are the result of the variety of opinions, ideas, and case studies in Harmony. Readers may find they disagree or agree with how topics are addressed or with a set of topics that have emerged. Such was the intent of Harmony: to stimulate discussion and evaluate how to further preserve the richness of the symphony orchestra in our society!Importantly, the themes that emerged are the work of several contributors in Harmony. This paper merely structures and organizes the work of many authors to guide the reader into investigating in greater depth topics of interest. The use of terms, such as “customer”, “audience”, “product”, and “program”, therefore, are drawn from the articles.

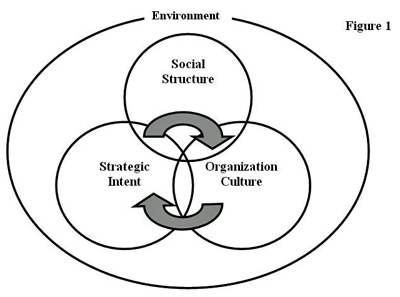

In the process of mapping out all the articles published in Harmony over its eight-year life, four characteristic domains or categories emerged.(Figure 1.) The domains are: social structure; organizational culture; strategic intent; and changes in the environment.

Representing pressures to the orchestra, which require orchestras to adapt, is the general environment. As such, the environment also provides for the context of the internal domains identified in the Harmony literature: social structure; organizational culture; and strategic intent.

Importantly, each organizational domain is both interrelated and partially a causation to the other domains as indicated by the arrows and overlapping circles. Put another way, the domains are related and causally ambiguous. The reader should see the domains not in an order of causation where one domain must cause the next specific domain to emerge.Rather, it is more useful to see that they simultaneously cause other domains to emerge given their close relationship to each other and overlapping characteristics. This approach to seeing the model removes the assumption that one domain must first be present before the next emerges. It is more useful to see that if any changes in orchestra practices are applied, or any attempt to understand orchestra organization dynamics, that they will necessarily be accomplished through understanding all three domains of social structure, organizational culture and strategic intent.

Each organizational domain that emerged was a result of (1) orchestras implementing changes resistance by musician and/or public occurs; and/or (2) writers articulating that if changes occur, resistance by musicians and/or the public will also surface. This parallel’s Boulez (1986):

“Try, for instance, simply as a matter of organization, to modify the constitution of an orchestra. You will see that you will almost encounter deep hostility, from both public and players, who will tell you that it has worked very well as it is: why should it not continue to do so, with a few adjustments?”

Implementing changes, discussing changes, or suggesting changes necessarily challenges established structures, cultures, and organizational purpose.

As a map to further reading the eight years of Harmony, each domain is examined in greater detail below by identifying key organizational elements.Following each domain, Tables I, II, III and IV list articles by author, title, and issue for further reading and/or research in Harmony. Note that articles between the three domains will overlap since each domain is closely related.For example, the topic of integrating musician input into the process of concert programming necessarily lends itself to the topics of organizational culture, governance, and even strategic planning.

Social Structure

Social structure is the different divisions, departments, work skills, tasks, leadership, and their relationship in the organization. Max Weber (1964) conceived of social structure as being in three parts: hierarchy of authority, division of labor, and coordinating mechanisms (formal procedures and rules). Each part of a social structure is characterized by differentiation. For example, there are different levels of authority and different types of authority; there are different skill sets, knowledge sets, and organizational tasks; and there are various procedures, processes, and routines that coordinate the varied authority and task differences.In essence, differentiation drives the need for integration. (Hatch, 1990)

Social structure is characterized by this dual tension of differentiation and integration. For an orchestra, social structure is the varied instrument sections, management, the board, the conductor, and musicians.It is within these differentiated areas where Weber’s scheme sheds light on some fundamental problems associated with integrating the orchestra social structure.

Many elements of the structure problems documented in the course of eight years of Harmony were the result of orchestras attempting to move away from established modes (i.e. traditional) of operation to revised modes of operation: orchestras attempting to apply organizational change—a driving and central theme of Harmony. A vision of organizational change in orchestras can be seen early in Harmony with Boulian, (1997), Judy (1997), and Editorial commentary (1998) all of which focus on generating progressive solutions for orchestra’s social structure, strategic, cultural, and environmental challenges. However, implementing changes generates resistance from both the orchestra and even the public (Boulez, 1986). Importantly, as studies and opinions in Harmony focused on moving towards organizational change in orchestras, the following problem elements of social structure emerged:

Social Structure Problem—a lack of integrating differentiated sections of the organization in support of instituting organizational change.

Elements of the domain problem under Weber’s construct: Hierarchy of Authority

- Governance, Structural Ambiguity, and Structural Experimentation Division of Labor

- Management, Conductor, and Musician tensions/disagreements Coordination Mechanisms

- Musician input towards developing organization direction (artistic, governance, etc).

Hierarchy of Authority: Governance and Structural Ambiguity

Orchestras attempting to institute organizational change encountered the pressures associated with integrating the organization. Specifically, making changes required new forms of integration. Areas requiring change and in turn creating integration pressures were found in the board/management and the conductor. Orchestras have functioned under traditional structures and assumptions for years and breaking the crust of such tradition was the essential challenge set forth by a number of authors. Yet changing traditional structures brought about integration problems based on long-held assumptions of management v. musician tensions.Authority and governance structures seemed ambiguous or experimental because changes implemented generated new problems of integration.

A dominant area that characterized the structural change in governance—the hierarchy of authority—was that of musician input (Pollack, 1996) and the problem that such input either does not exist or is limited in scope.(Levine and Levine, 1996) This type of organizational change has a direct impact on traditional modes of operation for orchestras. Given the assumption of management v. musician, the lack of trust between the groups further heightened the need for determining the role of authority structures in orchestras, yielding a degree of disorientation, ambiguity, or lack of clarity for boards, conductors, and management.

Areas of discussion were self-governance through a network of committees (Zenone, Judy and Scholl, 1999; Editors, 1999; Lehman, 1999) in conjunction with examining orchestra board effectiveness. (Goodell, 1999; Judy, 1999) Structures that emphasized equality, self-governance and like minded visions were imperative towards furthering the need to integrate the social structure of orchestras given new authority structures. (Editors, 1999; Lehman, 1999) Fogel (2000) provided an incisive examination on the nature of the existing governance structure with practical areas for improvement such as including musicians on orchestra decisions and generating trust throughout the organization. By suggesting the alignment of board duties to reflect those of corporate boards, Fogel’s (2000) model provides a basis for orchestras to integrate the diversity of constituents toward a common goal. One way to confront the challenges of changing the structures was to narrow the scope of Board duties (Noteboom 2002) since successful orchestra organizations were linked to strong boards and leadership.(Morris, 2002; Boulin, 2002; Valliere, 2002; Editors, 2002)

A second area of authority structures that went through changes was the role, place, and leadership of the conductor. The place of the music director, while critically examined in many Harmony issues, was best evaluated in Editors (2001(c)) and Levine (2001). While the current conductor model in orchestras is efficient, (Levine, 2001) as in industrial production, it contributes less towards a fully integrated post-industrial approach. (Levine, 2001; Zenone, 2001)No alternative models exist, yet the model engenders ill organizational health by not integrating the full resources of musicians at different levels. (Levine, 2001; Zenone, 2001; Editors, 2001(c); Starr, 2001) Since music direction is centered on the conductor, the lack of musician input—the producers of the music experience—remains untapped in many orchestra organizations. (Zenone, 2001) Importantly, Wolf and Perille (2002) emphasized defining the conductor’s role in relation to the unique qualities of different orchestras.The “one size does not fit all” was a common theme in devising and defining processes—a progressive step in integrating the social structure of orchestras in a way that reflects post-industrial organizations. (Stearns, 2002; Wagner and Ward, 2002; Editors, 2002(a))

Division of Labor: Management, Conductor and. Musicians

Differentiation of skills, tasks, perspectives, and roles punctuated the long-held tensions between management, musicians, and the conductor.Rooted in management v. musician assumptions, (Levine and Levine, 1996; Freeman, 1996; Schnitz, 1996) lack of musician input with regards to the organization was a natural outcome. The first issues of Harmony in 1997 examined the problem of limited musician input which continued to remain a topic of examination over the eight years of publication. Subcultures and the development thereof in organizations were defined as barriers that potentially limit integration. (Eisen, 2000; Editors, 2000) Metaphors, such as the Starfish, provided provocative analogies to understanding how organizations that are not effectively integrated move different directions. (Eisen, 2000) Different directions pull apart the organization, and therefore, impede organizational change.

While the conductor—orchestra modelis efficient, many issues were critical of the type of organizational health such a structure created. Again, differentiation of tasks and roles—between the conductor and musicians—generated pressures to integrate.Because organizational change implemented musician input, new pressures to integrate and define each role between the conductor and musicians were attempted through committees, meetings, and other group approaches.

Coordination Mechanisms: Participatory Structures

Coordination mechanisms are used towards integrating differentiation in an organization. They can be rules, processes, and procedures.Harmony introduced various forms of integrating the tensions between management, musicians, and conductors. Since artistic organizations thrive on creativity, integration of the social structure is a sound goal to achieve.(Maciariello, 2003; Toeplitz, 2003)

Participatory structures were introduced where musicians become parts of committees or decision making or through examples of other orchestras. (Maitlis, 1997; Judy, 1997; Editors, 1997; Bachetti, 1997, Editors, 2001(b)) This approach of participatory structures is both an organizational change and a tool of integration. Participatory structures and the use of techniques to further develop organizational trust were approached as a means to integrate the organization, while potentially tapping into the creativity of all internal constituents in an orchestra. (Stearns, 1998; Toeplitz, 1998, Editors, 2001(b)) Varied participatory structures like committees, task groups, and other self-governing tools also serve to bring together varied subcultures. Though structures were participatory in idea and application, the board in orchestras was seen to provide vision, direction and strategic intent.

Additionally, the use of appreciative inquiry techniques, questioning that keeps the strengths of the organization as the subject, were described as approaches in defining values and purpose of orchestras with the intent towards integrating the social structure. (Stearns, 2002; Wagner and Ward, 2002) By examining processes and recognizing the lack of processes were at fault and not people, was another step towards changing and integrating the structures of orchestras. (Stearns, 2002) Table I details the articles in chronological order by Social Structure Domain and by Author.

Click here to see Table I: Social Structure

Organizational Culture

An organization’s culture constitutes the basis of what individuals believe, hold valuable, and act out in everyday activities. As such, organizational culture provides explanations as to why certain individual actions are legitimate within the organization. Schein (1992) posits that organizational culture is based on three levels: assumptions, values, and norms. Basic underlying assumptions are unconscious, taken-for-granted beliefs, perceptions, thoughts, and feelings—all are the ultimate source of values and action (Schein, 1992). Values specify what is important to individuals and norms establish the basis for behavior between individuals.

A clash between implementing organizational change and held cultural assumptions, values, and norms provides for the dominant pattern over the eight years of Harmony. That is, implementing organizational change was a direct contrast to an established organizational cultural found in orchestras. Three areas emerged as problems based on the implementing organizational change vs. organizational culture of orchestras: the persistence of organizational traditions; the tensions of making progress while attempting to preserve the past; and the acceptance of the management, musician, and conductor tensions in relationships. The following table details the relationship of the three areas found in Harmony with Schien’s (1992) levels of organizational culture:

Organizational Culture Problem—Orchestra culture is characterized by rigid structures based on held traditions and deeply rooted assumptions that are in contrast to organizational changes designed to alter how orchestras operate.

Elements of the domain problem under Schein’s 3 levels of culture:

Each problem area identified in organizational culture is a manifestation of Schein’s three levels of culture.

Persistence of Organizational Traditions

- Assumptions—taken for granted ways of thinking about the orchestra’s traditional ways of operating.

- Values—important values that define how routine work is accomplished.

- Norms—expected ways of acting out values and traditional ways of operating.

Tensions of Progress v. Preserving the Past

- Assumptions—taken for granted ways of thinking about what orchestras do in contrast to implemented organizational changes.

- Values—important values defining routine work are challenged by organizational changes.

- Norms—expected ways of behavior are challenged—particularly the differences between management, musicians, and conductor.

Accepted Tension between Management, Musicians, and Conductor

- Assumptions—taken for granted tension of management, musicians, and conductor.

- Values—defined expectations about others and their place in the orchestra.

- Norms—expected ways of behavior between individuals.

Persistence of Organizational Traditions

Questioning practices of orchestra organizations in the early issues of Harmony (1995 and 1996) was an indication that some degree of change was required for orchestras in the 21st century. (Judy, 1995 and 1996; Freeman, 1996; Hope, 1996) Orchestras had to realize that abandoning certain practices and traditions may be essential to future viability. (Hope, 1996; Freeman, 1996) That traditions needed to be abandoned emerged as a theme since organizational changes being applied clashed with the existing culture in orchestras. Common traditions examined were how concerts are prepared; the relationship between management, musician, and conductor; how concerts are presented to the public; and the type of music that will be part of the program.

Virkhaus (1997) posited that metaphors and myths are integral to how orchestras operate and as such, suggested revitalizing such myths and metaphors rather than completely displacing them.Revitalizing the myths and revising them at the same time provides a vision of where the orchestra can go while also generating mutual responsiveness in the organization. (Virkhaus, 1997; Fischer and Jackson, 1997) Traditionally, the three areas of musician, management, and conductor have operated as being at odds with each other. Bringing musicians into both the decision process and planning process yielded a structural change requiring a re-examination of cultural values. (Zenone, 2000, Eisen, 2000)

Judy (1999) stated that the orchestra organization is being “dragged, kicked and screaming into the 21st century” given its deeply held assumptions.These are assumptions surrounding the conductor, musicians, artistic direction, repertoire, and boards, yielding cultural inertia. (Spich and Sylvester, 1999; Judy, 1999)In sum, the imperative of abandoning traditions behind required a mind shift. (Toeplitz, 2003; Maciariello, 2003)Orchestras seem to “preserve ignorance of forward thinking” (Toeplitz, 2003) and resistant to solutions or learning outside antiquated and existing orchestra organization models. (Maciariello, 2003)Yet, such traditions can be revitalized rather than completely displaced.(Fischer and Jackson, 1997) The pair of abandoning, yet revitalizing traditions is the next theme examined.

Tensions of Progress v. Preserving the Past

In his essay, Tradition and the Individual Talent, T.S. Eliot describes the tensions of preserving the past yet progressing forward in poetry. Thematically, orchestras face the same tensions in attempts at instituting change since organizational culture provides the fabric of meaning to what and how orchestras accomplish their purpose. This tension was characterized by the necessity of orchestras continuing to preserve the classical repertoire, yet at the same time, change operationally how the repertoire is presented.How the repertoire is preserved is based on long-held traditions, which are in contrast to changes made in how orchestras operate.

Changes in the organizational culture were needed and could be accomplished by understanding how behaviors were tied to traditions.(Orleans, 1997; Starr, 1997; Fischer and Jackson, 1997; Virkhaus, 1997) Values in orchestras, the domain that specifies what is important to individuals, clashed with organizational change applications. Yet focusing on an organization’s values provides a basis to measuring the nature of change in the organization. If values are the imperatives that drive orchestras, success could possibly be evaluated or measured. (Zenone, Judy and Scholl, 1999; Goodell, 1999; Spich and Sylvester, 1999; Judy, 1999(a)) Cultural inertia, though, keeps orchestras from moving towards full organizational change—moving from the safety of traditions and mimesis. (Spich and Sylvester, 1999; Judy, 1999(a))

Judy (1999(a)) asserts that a culture in the orchestra must exist towards meeting organizational effectiveness. In other words, if orchestras are to change how they operate, then the culture must first change. Wiegold (2001) posits that regenerating an existing culture from one in stasis to one that can preserve tradition while generating the new is imperative. Yet accomplishing “preserving and progressing” simultaneously requires immense effort. (Wiegold 2001) Abandoning traditions in order to implement changesrequires a mind shift for all constituents in orchestras. (Toeplitz, 2003; Maciariello, 2003)

To conclude: Preserving a rich tradition while simultaneously moving forward was a tension identified as problematic since orchestras do preserve a classical repertoire yet the means to generating (i.e. operations) the music needs changing. Thematic in examining traditions in orchestras was the idea of revitalizing such traditions while also abandoning some traditions.

Accepted Tension between Management, Musicians, and Conductor

Long held assumptions of differences in management (including the Board), musicians, and conductor remained a topic of Harmony over the eight years of publication. Barriers based on differentiated skills and tasks from different groups; differences in opinion on orchestra purpose;differences in labor negotiation values; differences in program content; and differences in what constitutes leadership, all contributed towards further cultivating held assumptions of accepted tensions between various groups in orchestras. As such, the tensions between the groups heightened by various barriers separating each group, was centered on the lack of musician input with regards to the organization.(Levine and Levine, 1996; Freeman, 1996; Schnitz, 1996) The first issues of Harmony examined the problem of limited musician input which continued to remain a topic of repeated examination over the eight years of publication.

Accepting the given tension, or at least notable differences, between management, musicians, and conductor punctuated the need of bringing together the different groups in the organization as a whole. (Judy, 1998; Cahn, 1998; Toeplitz, 1998; Stearns, 1998; Spich and Sylvester, 1998) While an organization may exhibit organizational inertia, (Spich and Sylvester, 1998) it can do so even with different culture groups operating together. (Stearns, 1998; Spich and Sylvester, 1998) By integrating groups, levels of trust increase and the move to integrating the social structure begins.(Stearns, 1998; Toeplitz, 1998) The result of integration yields a common vision to the music—the very tradition of preserving the repertoire.

Improving the elements of communication to reduce management versus musician tensions was approached as a means to revitalize the organizational culture. (Goodell, 1999) Since assumptions are deeply held organizational wide, opening up the lines of communication through shared values was an approach to not changing the entire culture, but to tap into the culture where agreements of assumptions could be found. (Goodell, 1999; Zenone, Judy and Scholl, 1999)

Cultural groups were again identified in some of the 2000 Harmony issues.(Editors, 2000; Eisen, 2000; Zenone, 2000; Fogel, 2000) Specifically, the tensions between musicians and management was highlighted, (Zenone, 2000; Eisen, 2000, Editors, 2001(b)) as in other issues, as subculture groups develop their own shared assumptions about the organization. (Eisen, 2000; Fogel, 2000)Subcultures create barriers, which fostered mistrust and mistrust fueled continual cultural inertia and lack of social structure integration. (Eisen, 2000) While each group cultivated its shared assumptions, ambiguity of focus resulted. (Zenone, 2000) The starfish metaphor was used to illustrate how each subculture group—an arm of a starfish—would move different directions effectively generating a self-destructive pattern for a starfish. (Eisen, 2000)

Critical areas of cultural antagonism between musicians and a conductor were pointed out in Levine (2001): the music director (conductor) determines performance and artistic direction; the music director is the chief performer; there is audience applause when the conductor appears on stage; the focus of the audience seems to be on the conductor who is standing and in front versus the faceless mass of the orchestra.Such perceptions further cultivate tensions between management, musicians, and conductor. (Schuller 2001; Wiegold, 2001; Starr, 2001; Levine 2001). Continued pockets of antagonism persist since it is easier to harbor old assumptions versus questioning assumptions which can generate changed values. (Schuller 2001; Starr, 2001; and Levine 2001)

Changing organizational culture requires action that proves alternative assumptions can in fact be reliable and thus relevant (Schein 1992).Organizational culture is to be collaborative and thus social structure changes can provide a path towards implementing new values (Valliere, 2002). The value of musician input is demonstrated by including them in teams and ad hoc committees in working towards organizational goals. (Boulian, 2002; Editors, 2002; Wagner and Ward, 2002; Stearns, 2002) Taking such action yields proof that new values can potentially transforms an antagonistic organizational culture (Wagner and Ward, 2002).

Table II details the articles in chronological order by Organizational Culture Domain and by Author.

Click here to see Table II: Organizational Culture

Strategic Intent and Action

Strategic intent means an organization can set a vision, sustain a purpose, plan, and remain focused while adapting to changing conditions in the environment (Hamel and Prahalad, 1989). Strategic action is making the intent real and played out using the capabilities of the organization.

The pattern found in Harmony was that strategic intent and action by orchestra organizations was difficult to achieve principally because of un-integrated social structures and cultural inertia.Dominant problems in strategic intent and action were in the lack of strategic intent or strategic planning; mimesis—doing what “worked” in the past;product development/innovation; building audiences/customers.

A better understanding of the strategic problems in orchestras is accomplished by framing them using two key concepts in management theory. First is Porter’s (1985) construct of SWOT—Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats. Second is Barney’s (1991) construct of the Resource Based-View of Organizations—RSBV.

First, a brief definition of SWOT: Strengths and Weaknesses are directly related to what the orchestra is capable of doing and not doing with respect to Opportunities and Threats found in the environment outside of the orchestra. Opportunities are positive characteristics in the environment that are favorable for orchestras where as Threats are negative and potentially dangerous to an orchestra’s continued operations. Second, what is RSBV? The resource-based view holds that organizations are bundles of resources that are configured through strategic planning and action in response to environmental opportunities and threats. Thus, Strengths and Weaknesses describe the merits of the configured resources and capabilities of an organization.

In this section, all of the strategic problems are primarily connected with Strengths and Weaknesses. And since the focus is on Strengths and Weaknesses, the discussion centers on the resources and capabilities available to orchestras that can be configured for strategic advantage through intent and action. Opportunities and Threats, the external environment of the orchestra, is covered in the next section. The following table summarizes the strategic problems under the SWOT and RSBV framework.

Strategic Intent and Action—thinking and acting strategically are primarily constrained by fragmented social structures and the persistence of cultural inertia.

Domain problem based on SWOT & RSBV:

Strengths/Weaknesses

- Lack of Strategic Intent/Need for Strategic Planning

RSBV: Generating intent by developing strategic thinking and evaluating available resources.

Strengths/Weaknesses

- Mimetic Responses—doing what “worked” in the past.

RSBV: Ignoring strategic intent and action by reverting to actions that feel “safe”.

Strengths/Weaknesses

- Product Development/Innovation

RSBV: Intent into action using existing resources and capabilities.

Strengths/Weaknesses

- Building Audiences/CustomersRSBV: Intent into action using existing resources and capabilities.

The Need for Strategic Planning and Thinking

In the area of planning and thinking strategically, the issues of Harmony in 1996 introduced findings that strategy is not necessarily an ongoing activity, or concept, or a developed way of thinking in orchestras. (Freeman, 1996; Judy, 1995) Deliberately implementing a plan to strategically grow and respond to the environment was a relatively new approach for orchestras that have operated out of static tradition and fragmented social structures. (Hope, 1996) Articles discussed the possibility of abandoning traditions while developing strategic thinking; unique strategies that reflect different types of orchestras; vague mission and purpose; misalignment of orchestra purpose and pot.

No comments yet.

Add your comment