Spotlight on Australian Symphony Orchestras: the past, the present, the future

Background

Australia is a country with roughly the same landmass as the continental United States, but only has a population of just over 20 million. There are six states (New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, Tasmania, Western Australia, and Queensland) and two territories (Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory), although the bulk of the population lives on the eastern edge of the country. In each state, the largest city (in Australia, this is always the capital) is more than twice the size of the second largest, a phenomenon which is known as the primate city. This means that larger regional centers do not have populations large enough to support major arts organizations and rely on ‘the big smoke’ to provide them. Australia is also very liberal politically and has long traditions of social security and public education. The arts are largely publicly funded both through the Australia Council for the Arts and directly from the state and federal governments. There is virtually no tradition of philanthropy and arts organizations do not typically have any endowment whatsoever. The season runs with the calendar year, due to the seasons in the Southern Hemisphere.

There are currently six symphony and two pit orchestras in Australia as listed below:

Sydney Symphony Orchestra (SSO)

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra (MSO)

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra (ASO)

Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra (TSO)

Western Australian Symphony Orchestra (WASO)

The Queensland Orchestra (TQO)

Australian Opera and Ballet Orchestra (AOBO)

Orchestra Victoria (OV)

The Past

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) is the national (federally funded) radio, online and television broadcaster. In the 1930s and 1940s, the ABC collaborated with the state governments and the then amateur orchestra societies to form full-time professional symphony orchestras. Their purpose was to perform concerts and radio broadcasts. As a result of the ABC’s involvement, all musicians were treated as government employees with excellent superannuation (retirement) packages (health care in Australia is free, so health insurance is never offered as a benefit). However, in the 1990s it was decided that the orchestras should be more distinct, with government funding administered directly to each orchestra. At this time Symphony Australia was formed to continue to provide professional services to the orchestras, albeit at a cost.

Symphony Australia continues to provide vital services to the orchestras such as the National Music Library (NML). Although each orchestra maintains a small private collection, much of the music they use is borrowed from the NML. Although the larger orchestras in Sydney and Melbourne would be able to fund larger orchestral libraries, this pooling of resources reduces the need for the regional orchestras to maintain their own collection.

The Present

Paul Blackman, ASO bassoonist and National President of the Symphony Orchestra Musician’s Union (SOMA) was kind enough to provide me with a copy of the ASO’s Enterprise Bargaining Agreement 2006 (Master Contract). The following facts about orchestral employment are taken from this and “A New Era: Report of the Orchestras Review 2005”, known as the Strong Report

Working conditions for Australian musicians are fairly good compared to many of their US counterparts. As of January 1, 2007, all symphony orchestras are now totally independent of the ABC and as a result some current industrial arrangements are being renegotiated. Players who were members before the break from the ABC still receive government superannuation (retirement) packages, which are deemed to be superior to those in the private sector. Newer employees may well be offered considerably less. The Australian government requires by law that all employers contribute an amount equal to a minimum of 9% of each employee’s income to a superannuation fund. Across the country, musicians also receive a range of a dress allowances ($140 per annum in the ASO is one of the lower payments), and instrument allowances.

Orchestral players generally play 32 calls per four-week cycle. Call counts include non-playing calls such as auditions and meetings. Each call is 2.5 hrs long, except for dress rehearsals, performances, and operas. They receive five weeks of annual leave (plus 17.5% loading) plus a one-week mid-year break and generous sick leave. After ten years of service, musicians are able to take long service leave, which entitles them to 3 months of leave at full pay plus loading (percentage bonus), or 6 months at half pay.

In 2003, starting tutti salaries at the orchestras ranged from AUD $37,350 – $64,000 for inexperienced players to AUD $46,630 – $76,800 for the more experienced, with yearly incremental increases. In addition, total salary packages include allowances as above, leave loading, and may include parking (this is significant for the SSO – their home is now the Sydney Opera House). Currently, players who perform in a smaller ensemble of fewer than 8 members receive a 33 1/3% loading, although this may change in the near future.

The ongoing issue of Loss of Proficiency is addressed in the ASO Agreement and is formalized with specific guidelines. There is also a clause regarding the use of hearing protection: “Notwithstanding the loss of proficiency provisions detailed in this agreement, where loud works are to be rehearsed and certain players use hearing protection, it is recognized that the wearing of such devices may compromise the player’s best performance standard. It is also recognized that hearing protectors make playing in tune and with correct attention to balance more difficult, and therefore criticism of a player on these grounds alone during a period when any musician is required to wear hearing protection adequate for the industry, shall not, of itself, provide evidence of an unacceptable decline in playing ability and overall performance. ” This is designed to encourage players to use hearing protection even though it may affect their overall performance.

All of the orchestras also provide players with the Tempo Chairs . These ergonomic chairs were designed in consultation with the players of the SSO and the stage technicians of the Sydney Opera House and are almost infinitely adjustable. The front and rear leg heights are independently adjustable, as is the height of the backrest and depth of the seat. They are also designed specifically for orchestral musicians so they look attractive and appropriate on stage.

There are two unions covering players in Australia: the Musician\’s Union of Australia (MUA) and the Symphony Orchestra Musicians Association (SOMA), part of the giant Media, Arts and Entertainment Alliance. For all practical purposes, the MUA has lost relevance in the workplace. Although membership to these unions is not compulsory, well over 90% of orchestral players are members of SOMA with over 620 members nationally. This level of membership by percentage is among the highest in the country for all unions. SOMA represents musicians in much the same way that the American Federation of Musicians does in the US and Canada.

Auditions for the orchestras are advertised on the Internet and in the major Australian newspapers. Positions are auditioned at least twice for Australian residents before they may be opened up to international applicants. The procedure for auditioning is much the same as US orchestras, except that excerpts are generally not released until two weeks before the audition. At this point, players may pick up their audition packet from their local orchestra. A full set of the music required will be contained in this packet, with the excerpts marked clearly. Other differences include the solo repertoire required. For example, viola auditions may require both a classical and romantic concerto, whereas in the US, only the romantic concerto is required. This is more in line with European orchestras.

All of the orchestras offer tenure to their players, typically after a six-month trial. In the ASO agreement, the trial process has been formalized with review and feedback dates.

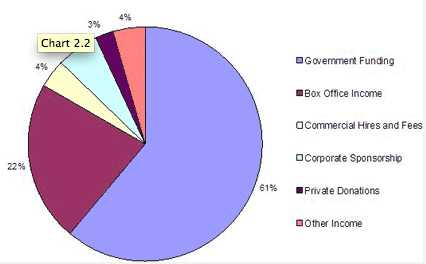

Australian orchestras face slightly different challenges when it comes to revenue, as they were never conceived as self-supporting organizations. Funding for the orchestras (as a total) comes from a variety of sources: government (61%), corporate sponsorship (6%), box office (22%), commercial hires (4%), private donations (3%) and other sources (4%) .

As each capital city supports a full-time orchestra, regardless of the population, the budget for each is not necessarily commensurate with the size of the audience pool. The table below shows the size of the orchestra, population of the city and the operating budget for 2003.

As we can see from the above data, Hobart, the home city of the TSO has a very small population. It is therefore not reasonable that they should be able to be self-funding from box office and other revenue. Box office sales can also be compared to the population over 18 years of ages. The TSO shows the highest number of paid attendances per 1000, at 98.5; and TQO the lowest at 23.3 . The total audience in the period 2001-2003 is almost a million per year – a substantial percentage of the total population.

The Future

Australian orchestras do face similar financial challenges as elsewhere, and a major report was commissioned by the Australian government into the future of orchestras in Australia. “A New Era: Report of the Orchestras Review 2005” was lead by James Strong, a prominent figure in the business world, having been the CEO of Qantas Airways from 1993-2001. This report had many recommendations to secure the future of the orchestras and is interesting as it was carried out from a private sector point of view. It was not suggested that government funding ever be removed, but that orchestras should strive to be more financially viable.

Interestingly, one of the key recommendations was that each orchestra should fully extricate themselves from the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) and become public companies. Each state government would then eliminate all accrued deficit in order for the companies to begin at ‘ground zero’. Other recommendations (currently up for renegotiation), which more directly affect musician’s working conditions include the following: new employees of the orchestras should have a superannuation scheme more in line with the “current community standard” , exclusion of non-playing calls from the call count, removal of the chamber loading, reduction of the loss of proficiency provision from 77 weeks to 48 weeks, development of formal structures to assess loss of proficiency. The report also recommended that TQO, ASO, and TSO reduce their size to double wind orchestras, although after a vigorous campaign in the media by SOMA and the correspondingly strong public reaction, this recommendation was dropped. The full implications of this report have not yet been felt, and orchestras have recourse to the state governments regarding an increase in funding as well as federal lobbying tactics.

Following the recommendations of the Strong Report, as of January 1, 2007, all of the orchestras became fully divested of the ABC. This time of upheaval and transition may change the face of Australian Orchestras. It will be very interesting to see how the future of the Australian orchestra plays out.

Bibliography

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra http://www.aso.com.au/

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra http://www.mso.com.au/

Sydney Symphony Orchestra http://www.sydneysymphony.com/

Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra http://www.tso.com.au/

Western Australian Symphony Orchestra http://www.waso.com.au/

The Queensland Orchestra http://www.thequeenslandorchestra.com.au/

A New Era: Report of the Orchestras Review 2005. Australian Government, Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts. http://www.dcita.gov.au/orchestras

Tempo Chairs http://www.tecno.com.au/tempo_index.php

Acknowledgements

Paul Blackman, National President, Symphony Orchestra Musician’s Union

Karen Frost, Orchestral Manager, Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

Di Kidd, Communications Coordinator, Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

2. A New Era: Report of the Orchestras Review 2005. Australian Government.

3. A New Era: Report of the Orchestras Review 2005. Australian Government. pp. 45

4. Adelaide Symphony Orchestra Musicians Agreement 2006.

5. Adelaide Symphony Orchestra Musicians Agreement 2006. p. 27

6. http://www.tecno.com.au/tempo_index.php

7. A New Era: Report of the Orchestras Review 2005. Australian Government. pp.27

8. Data taken from orchestra’s websites, listed in bibliography

9. A New Era: Report of the Orchestras Review 2005. Australian Government. pp.26

10. A New Era: Report of the Orchestras Review 2005. Australian Government. pp.32

11. A New Era: Report of the Orchestras Review 2005. Australian Government. pp.15

12. A New Era: Report of the Orchestras Review 2005. Australian Government. pp.9

No comments yet.

Add your comment