Learning Through Music – From Implementation To Improvement

At the June 2006 American Symphony Orchestra League conference, acclaimed opera director Peter Sellars threw down the gantlet to all of us in the symphonic music business when he noted that we need to be in schools with the same fervor and commitment that inspired the message of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony: that we must break down boundaries in order that we can all be the brothers that we were created to be. Peter went on to say that orchestras were the elephants in the artistic ecology that frequently took up the most space and resources. Under the guise of transparent motives of service and sharing, he proposed that orchestras begin seeing their walls not as exclusionary, but as models of shared space. What he envisioned was music without borders, music with the power to heal, and music as social action.

This inspiring message begs the questions, “where do we start, how do we begin?” and “what are our goals?” Are we in the orchestral business only concerned with being in the “beauty business,” fiddling while Rome burns?

For me, exposing kids to classical music and creating the next generation of listeners and subscribers seems to be orchestras’ paramount goal; as such, we need to knock down that self imposed wall Peter Sellers identified. I submit that Sellars’ ideas of shared space include reframing music as literacy and it must engage teachers and musicians as active participants; we share their goals, hopes and dreams for the children.

Our current attempts at outreach and/or exposure unfortunately speak to our inbred Victorian roots that belie our attempts to keep the unwashed masses at arms length. We bring them our music on our terms and we somehow believe they are improved for our efforts. But to quote the famous opossum, Pogo, “We have met the enemy, and he is us.”

Orchestras labor mightily to reach children. Most school curricula painstakingly constructed by orchestra education departments end up in the trash bin and teachers’ participation is limited to glorified babysitting. Professional development for educational endeavors is often perfunctory or non-existent, treating teachers as apostles who sing the praises of symphonic repertoire. For most orchestras, the Youth Concerts serve as infotainment, meant to expose children to music, but not really instilling anything of educational value.

I felt that my frustration was getting the better of me and I awoke from a dream where in a flash of light I saw the connection between a school, my orchestra, and a research institution that might begin to push the envelope of what an orchestra could accomplish, other than entertain. In 1999, I became music director of the Kenwood Symphony, a civic orchestra, and decided that I could use that organization to channel my frustration and reach the vision from my dream into positive change at a grass roots level.

To some extent, most orchestras share a heightened sense of idealism, coupled with an entrenched and static self-image. For the amateurs, the orchestra is their private coffee klatsch whereas our “beauty business” phenomenon is a typical self perception among professionals. Both groups get stuck in the insularity that is bred by self selection and high comfort levels. Why change when you don’t have to? Let’s face it; it’s hard enough to make Beethoven sparkle night after night. I would argue, however, that both sets of musicians are searching for new meaning in their work, a reframing of personal and organizational goals.

After being at the helm of the Kenwood Symphony for a year or so, I knew that we would never play like the Minnesota Orchestra. But, I reasoned, we might become important in the lives of children. Opportunity knocked in the form of a challenge when the orchestra was kicked out of our residence; a Catholic Church that no longer had room in their rental schedule for our Monday evening rehearsals.

After canvassing the usual religious institutions for suitable replacement, an opportunity was presented to the KSO by one of our cellists who suggested the recently refurbished auditorium of her child’s K-8 school, the Ramsey International Fine Arts Center. Meetings were arranged and the Principal and I quickly came to terms: concerts in exchange of rent.

Ramsey is a fine arts magnet school where string instruction is required between 1st and 6th grades. After that point, students may switch to wind and percussion instruments if they wish. In addition to the instrumental instruction, the students receive general music lessons as well. In an educational landscape fraught with budget cuts to music programs, this school was an extraordinary landing spot for the KSO.

While visiting the school one day, I was struck by the nonchalance of the kids as they twirled their violins in the hallway – it reminded me of the students of the New England Conservatory’s Charter Lab School program founded by my friend, Dr. Larry Scripp. There, music integration is practiced as well as preached, and I imagined that Ramsey and the KSO might begin to explore a new kind of relationship, working off the blueprint of New England Conservatory’s Charter Lab School curriculum and assessment frameworks.

However, in order to prevent these ambitious plans from letting me get ahead of myself, I had to reconcile the KSO players not only to a new rehearsal and performance venue, but also to a new paradigm of success, predicated on some new and challenging relationships. Inspired by our move, the board, executive committee, and I decided that the time was right to reexamine our mission, making children and education central to our core commitment. We revised our mission statement by adding the phrase “bring learning to life.” I imagined a powerful and galvanizing pairing between an orchestra and a school, watched and regulated by a research institution, namely, the New England Conservatory Research Center for Learning Through Music (LTM).

Our first issue was that of space; we had to move out. Already there was a gnashing of teeth among the players but our new home could not have been more welcoming. For example, in addition to our original agreement they provided valuable storage space for our tympanis and music library in exchange for a couple of public concerts performed at the school.

On the school side of the equation, the KSO was interesting as a performing group, but the idea of music integration regulated by a research institution was equally enticing. The school’s Principal, Steve Norlin-Weaver, was so committed to a fruitful relationship that he specifically put the music integration program, LTM, into the school’s five year improvement plan as part of its differentiated instruction strategy. The orchestra would deliver music integration curricula while data and assessment would be handled by the New England Conservatory Research Center in Boston. This would provide Principal Norlin-Weaver with the data he needed to validate the connection between music and learning to counter the budget cuts he faced on an annual basis.

After the institutional lines had been drawn, it became a matter of KSO musicians and Ramsey teachers learning to go outside their comfort zones; we had to develop trust and to learn each other’s languages and cultures. Professional development for the orchestra was first. Some of our players had not been inside a classroom for 60 years. Then the classroom teachers had to find the shared fundamental concepts, i.e., proportion and tone, between music and their curricula. We all worked on meeting the standards set in the curricula.

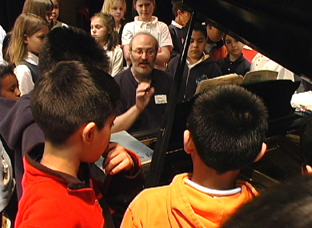

We began with a simple mentoring program that offered private lessons for students that couldn’t afford them. From there we developed our own version of the Pen Pal Program piloted at New England Conservatory: players would pair with teachers and classrooms to bring the lessons of La Boheme, Four Seasons, and Sorcerer’s Apprentice to the children. A CD and a letter were sent by players to classrooms, visits were arranged, and relationships slowly began to form. Suddenly, my players had new reasons to practice their parts. The players would appear in-person, introduce themselves by reading a story, and in some cases, team-teach the sketched out lessons of the music.

An original aspect of the program included weekend concerts, but they were ill attended in the first year. The next year, the Principal suggested that we perform more frequently throughout the year as a possible solution. He recommended we perform for the entire school on Friday mornings, then two concerts on Friday, then 3 concerts in one morning, twice a year with the kindergartners having shorter concerts Suddenly, teachers sensed our commitment to the children was sincere as players were sacrificing their paid work for them and the kids. All of a sudden, we were getting requests for repertoire by Mexican and African composers, for composers who tied their work to poetry, drama, and history. The school was “getting it.”

Financial support was provided by community leaders through the LTM Consulting Group. The LTM Consulting Group also wrote curricula and assessments that could be analyzed in Boston by the Research Center. Today there are about seven programs running in the school: musical interventions for struggling readers, 3rd grade music literacy and sight reading assessment, 4th grade opera tied to social studies, 2nd grade and 6th grade drum circles, digital composing after school, as well as the Pen Pal Project. In all projects, musical lessons are tied and measured with academic lessons. We are seeking to show the correlation between musical success and academic ability. Furthermore, we’re seeing classroom teachers coming out of the woodwork who have experience singing opera, majored in music, and are just merely curious in music as a teaching tool.

How did this all happen? Was it that the conductor stepped off the podium and took the reins to reframe the orchestra’s role in the community? Was it the reframing of the mission? Was it a rejuvenated sense of commitment and fulfillment from the players after seeing a thousand children respond personally and enthusiastically to their efforts?

My sense is all of these things contributed to the response. Moving the KSO’s rehearsal space from the church to the school forced us to reexamine many of our cherished beliefs memorialized in the mission. But it also provided a metaphor for moving out of our personal known space, our comfort zone, into new territory of philosophical real estate.

A principal and a conductor committed to a relationship and seeing where that relationship could lead are only limited by their own blinders and lack of imagination. To the children, we are the greatest orchestra on the face of the earth; we are their orchestra. We are there for the teachers, the administrators, and most importantly, for the children.

Like the musicians, redefining the insular and entrenched sense of self among the teachers has been empowering and invigorating. We invited teachers to ask and help answer their own research questions regarding music and learning as opposed to being the slave labor of the federally-mandated No Child Left Behind law. As a result of this program, increasingly better musicians are attracted to the orchestra every year. When we started, we were performing the equivalent of Telemann for every concert; now we perform Shostakovich and Mahler. Most importantly, the orchestra expects to be challenged.

Orchestras used to be an essential part of the community’s social fabric, playing at weddings, funerals, and dances. I strongly feel that our usefulness within the community has to be tied to more than the amount of beauty we send into the airwaves. We have to step off our stages and podiums to rethink the totality that is music. The effect of musical literacy on reading, the connection between keeping a steady beat and reading, and the effect that reading notes has on English as a Second Language students are all beginning to be better understood.

In the world of professional orchestral performing we take rhythm, decoding skills, and focus for granted in order to recreate the timeless beauty of the masters. Those skills essential to our success are also crucial to success in school. Rethinking our mission so that we do more than expose children to beauty, but rather teach them to read, think, and create musically helps us put music at the center of every child’s education—which is right where it belongs!

We need to refine our definition of music in education, as well as our sense of self, our self limiting blinders. It means being fearless in establishing new ties with the community by becoming activists for education reform. At the end of the day, it is about taking risks and who knows; maybe we can begin to build the audience of the future as well. An eighty year old cellist who helped found Kenwood Symphony 30 years ago helped me see this point when he paid me the highest possible compliment, saying, “This is what we had in mind when we started out all those years ago.”

Our journey of sharing space with a school has had its share of fits and starts. I organized a viola sectional one Monday night in a second grade classroom, clearing the chairs and desks for our players. When we finished we returned the chairs and desks to what we thought the class looked like when we came in. Unfortunately, we weren’t even close. The teacher called the Principal in a panic the next morning, thinking burglars had ransacked her class! Apologies were proffered all around and I learned a valuable lesson: Teachers regard their space as sacred, you should too! Mr. Sellars speaks to a model of shared space to which I would add: Cherish the space and cherish the sweetness of learning, and cherish our children. The rest will follow.

No comments yet.

Add your comment