The Ever-present Past

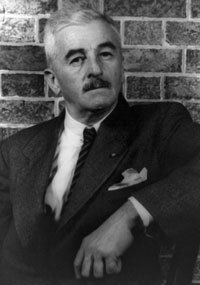

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” — William Faulkner

Faulkner’s truism from his strange novel/play, Requiem for a Nun, is one of my favorite lines and has been much quoted. Presidential candidate Barack Obama used a paraphrase of it in that eloquent 2008 speech defending his friendship with firebrand minister Jeremiah Wright. More recently, I found it curious to watch the progress of a lawsuit in which the Faulkner Literary Rights company sued Sony Pictures, distributors of Woody Allen’s best film in years, Midnight in Paris, for unauthorized use of the quotation by a character in the movie. (Literary Rights lost.) Actually, I don’t even remember the scene in question, but I do remember the wicked parody of Hemingway and his “grace under fire.” Presumably Hemingway’s estate is not so sensitive. But I digress…

Faulkner’s truism from his strange novel/play, Requiem for a Nun, is one of my favorite lines and has been much quoted. Presidential candidate Barack Obama used a paraphrase of it in that eloquent 2008 speech defending his friendship with firebrand minister Jeremiah Wright. More recently, I found it curious to watch the progress of a lawsuit in which the Faulkner Literary Rights company sued Sony Pictures, distributors of Woody Allen’s best film in years, Midnight in Paris, for unauthorized use of the quotation by a character in the movie. (Literary Rights lost.) Actually, I don’t even remember the scene in question, but I do remember the wicked parody of Hemingway and his “grace under fire.” Presumably Hemingway’s estate is not so sensitive. But I digress…

For me, the quote comes to mind whenever I contemplate an artwork from the past and experience that shock of contemporaneity that great works of genius so often ignite. No matter how far removed we might be in time and technological distance from, say, Homer or Thucydides, Shakespeare, Holbein, or Beethoven, they speak to us of a human condition we recognize. Our humanity, our humanness has never fundamentally changed. We still confront the same questions — about love, war, compassion, the existence of god and our relationship to the deity, the meaning of life, the right form of governance, jealousy, hatred, passion, joy, illness, death and what may or may not come afterward.

Here are a few of those moments in which the ever-present past becomes the ever-present present:

“Our Constitution does not copy the laws of neighboring states. We are rather a pattern to others than imitators ourselves. Its administration favors the many instead of the few: that is why it is called a democracy. If we look to the laws, they afford equal justice to all in their private differences; if no social standing, advancement in public life falls to reputation for capacity, class considerations not being allowed to interfere with merit; nor again does poverty bar the way, if a man is able to serve the state, he is not hindered by the obscurity of his condition.”

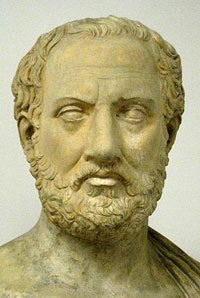

This extract comes from a book written over 2,400 years ago! The author is the Greek writer and historian, Thucydides, and he is recording his firsthand experiences in the Peloponnesian Wars, the major conflict from those ancient times between Athens and Sparta, a conflict that so resembles the political tensions of Russia and the U.S. during the Cold War and now, sadly, today. The quote comes from the funeral oration of Pericles, the ruler of Athens and was recorded by Thucydides at the time.

This extract comes from a book written over 2,400 years ago! The author is the Greek writer and historian, Thucydides, and he is recording his firsthand experiences in the Peloponnesian Wars, the major conflict from those ancient times between Athens and Sparta, a conflict that so resembles the political tensions of Russia and the U.S. during the Cold War and now, sadly, today. The quote comes from the funeral oration of Pericles, the ruler of Athens and was recorded by Thucydides at the time.

Thucydides’s writing has continued to cast resonating ripples throughout history. I think of John Adams (1725-1826), author of the Massachusetts Constitution, collaborator on the U.S. Constitution, second U.S. President, who was greatly influenced by Thucydides and urged his work (in the original Greek) on his son John Quincy: “You will find it full of Instruction to the Orator, the Statesman, the General, as well as to the Historian and the Philosopher.” Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address also echoes Thucydides as Gary Wills, pointed out in his book, Lincoln at Gettysburg.  And I thought of Thucydides again recently during the NEC performance of Joseph Schwantner’s New Morning for the World, narrated by Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick, with its settings of Martin Luther King’s texts. There was that astonishing line from the “I have a Dream Speech” where MLK envisions a future in which his children will “not be judged by the color of their skin but on the content of their character.”

And I thought of Thucydides again recently during the NEC performance of Joseph Schwantner’s New Morning for the World, narrated by Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick, with its settings of Martin Luther King’s texts. There was that astonishing line from the “I have a Dream Speech” where MLK envisions a future in which his children will “not be judged by the color of their skin but on the content of their character.”

There are also numerous paintings that have brought me up short with their startling contemporaneity. Consider several by Hans Holbein the Younger (1479-1540), Two of them hang in the Frick Gallery in New York City. The portraits of Sir Thomas More (Lord Chancellor of England) and Thomas Cromwell (Privy Councilor, Chancellor of the Exchequer, Secretary of State) glare at one another across the ancient enmity of 500 years, both in their fine robes of office as favorites of King Henry VIII (but not for long), frozen in their power and tragedies. Their rivalry seems a metaphor for all the poisonous competition for political favor across the centuries.

But another, even more extraordinary Holbein painting confronts me with all the power of a modern-day blow to the head. That is his depiction of The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb, (1520-22) housed in the Kunstmuseum, Öffentliche Kunstsammlung, Basel. A strikingly narrow horizontal work that mimics the claustrophobic confines of a coffin, this shockingly realistic portrayal shuns any romanticizing of the dead Christ. As scholar Barbara Fister has described it in a 1996 Kentucky Foreign Language Conference:

But another, even more extraordinary Holbein painting confronts me with all the power of a modern-day blow to the head. That is his depiction of The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb, (1520-22) housed in the Kunstmuseum, Öffentliche Kunstsammlung, Basel. A strikingly narrow horizontal work that mimics the claustrophobic confines of a coffin, this shockingly realistic portrayal shuns any romanticizing of the dead Christ. As scholar Barbara Fister has described it in a 1996 Kentucky Foreign Language Conference:

“The Holbein Christ is a naturalistic painting of a dead body. Its horizontal position, contorted hand, detailed musculature and disturbing face, with its eyes open but rolled back in the head, the mouth parted slackly, all emphasize death. The coloring of the painting is cold earth tones, emphasizing brown, gray, and muddy green, and the flesh tones are pale and bloodless. The only color is provided in the blood of the wounds.”

The possibility of this mortal being resurrected, of conquering sin and death for all mankind — the fundamental tenet of Christian faith — seems completely implausible.

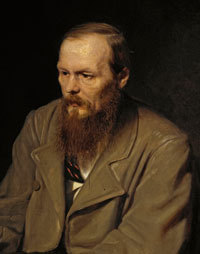

Indeed, the great Russian writer Feodor Dostoevsky was so haunted by the painting that he incorporated it in his novel, The Idiot. Hanging in the home of the murderous Rogozhin, the painting elicits very different responses from the “truly good man,” Prince Myshkin, and the villainous Rogozhin. The latter likes to look at the troubling image. The prince, however, is deeply repelled by it. “‘At that painting!’ he exclaims. ‘At that painting, a man could even lose his faith from that painting.’ ‘Lose it he does,’ Rogozhin suddenly agreed unexpectedly.”

Indeed, the great Russian writer Feodor Dostoevsky was so haunted by the painting that he incorporated it in his novel, The Idiot. Hanging in the home of the murderous Rogozhin, the painting elicits very different responses from the “truly good man,” Prince Myshkin, and the villainous Rogozhin. The latter likes to look at the troubling image. The prince, however, is deeply repelled by it. “‘At that painting!’ he exclaims. ‘At that painting, a man could even lose his faith from that painting.’ ‘Lose it he does,’ Rogozhin suddenly agreed unexpectedly.”

How amazing, how modern that a 16th-century painter could and would question orthodoxy in so blatant a manner. Without resorting to words, his picture embodies the rationalist’s doubt, expresses the questions that clearly existed in many 16th-century minds, centuries prior to the Enlightenment. And these are questions that still challenge us today.

Music from the past can also impress me with its modernity. A work that never ceases to amaze is Beethoven’s String Quartet Op. 130, written at the very end of the composer’s life in 1825. Like Holbein, it is contemporary, totally innovative, weird, compelling, strange and beautiful in the way difficult things can attract and become beautiful. It lasts between 45 and 50 minutes, has six movements, or seven if you count the substitute finale that replaced the Great Fugue.

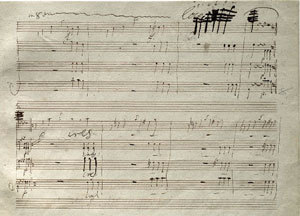

I have an old recording of the work by a great quartet that had a huge reputation for compellingly musical and intellectual interpretations in the first part of the 20th century — the Busch Quartet. I love this recording because there’s no attempt to sanitize the work’s oddness. The two-minute Presto, arrives and is then gone, but leaves an indelible image of desperate energy.  Just look at Beethoven’s scrawl as he is seemingly carried away with the direction he is trying desperately to capture on paper. The Alla danza tedesca, with its accordion-like swellings in every bar, is angular and remote and vulnerable. But the Cavatina… now that’s something. Its idea is simple, just as the title suggests, a small song. However, then, there is a central section that sounds as though it has arrived from Saturn’s moon “Enceladus” or from an improvisation by Thelonious Monk. It always makes me puzzled and awestruck in equal measures. The last movement, the Great Fugue, I have never come to terms with after all these years. And I’m not the only one. As one commentator has remarked, “If ‘difficult’ was ever perfectly applied to Beethoven’s music, the Great Fugue is the single most deserving work beyond question.” And it’s not so much that it was a fugal movement closing a string quartet but one extraordinary for its length (about 16 minutes), expressive intensity, and unrelenting dissonance. That’s what makes it so fascinating and so modern seeming. Indeed, no less a composer than Igor Stravinsky famously remarked about the Great Fugue, “[it is] an absolutely contemporary piece of music that will be contemporary forever.”

Just look at Beethoven’s scrawl as he is seemingly carried away with the direction he is trying desperately to capture on paper. The Alla danza tedesca, with its accordion-like swellings in every bar, is angular and remote and vulnerable. But the Cavatina… now that’s something. Its idea is simple, just as the title suggests, a small song. However, then, there is a central section that sounds as though it has arrived from Saturn’s moon “Enceladus” or from an improvisation by Thelonious Monk. It always makes me puzzled and awestruck in equal measures. The last movement, the Great Fugue, I have never come to terms with after all these years. And I’m not the only one. As one commentator has remarked, “If ‘difficult’ was ever perfectly applied to Beethoven’s music, the Great Fugue is the single most deserving work beyond question.” And it’s not so much that it was a fugal movement closing a string quartet but one extraordinary for its length (about 16 minutes), expressive intensity, and unrelenting dissonance. That’s what makes it so fascinating and so modern seeming. Indeed, no less a composer than Igor Stravinsky famously remarked about the Great Fugue, “[it is] an absolutely contemporary piece of music that will be contemporary forever.”

P.S. Oh, and by the way… if Beethoven were a student today studying at NEC, he would be a key member of our Contemporary Improvisation department!

No comments yet.

Add your comment