Being in Tune

The Guildhall School of Music & Drama, housed at the Barbican in London, is an extraordinary cauldron of invention. It teaches some of the finest young musicians and actors, has community partnerships across the whole of London, and promotes vigorous and highly creative collaborations with the Barbican Centre itself and its major resident company the London Symphony Orchestra.

The Guildhall School of Music & Drama, housed at the Barbican in London, is an extraordinary cauldron of invention. It teaches some of the finest young musicians and actors, has community partnerships across the whole of London, and promotes vigorous and highly creative collaborations with the Barbican Centre itself and its major resident company the London Symphony Orchestra.

Besides having a stellar faculty and excellent programs in opera, chamber music, orchestral studies and jazz, the school also extends its work into research and knowledge exchange illuminating the inter-relationships between repertoire for the 21st Century, the science and art of artistry, and performance practices. It also has a Masters pathway in leadership, the intention of which is to extend the boundaries of performance through improvisation, group composition, cross arts collaboration, creative workshops and international placements (NEC and the Guildhall are already discussing a collaborative project in Tanzania for next year).  In September this year the School opened the brand new Milton Court, a multi-million dollar building funded through a public/private partnership which includes a 600 seat concert hall, a 223 seat theatre, a studio theatre, and rehearsal space, all supported by state of the art technology. It is an astonishing development and one that has created a great deal of interest in the city.

In September this year the School opened the brand new Milton Court, a multi-million dollar building funded through a public/private partnership which includes a 600 seat concert hall, a 223 seat theatre, a studio theatre, and rehearsal space, all supported by state of the art technology. It is an astonishing development and one that has created a great deal of interest in the city.

Like all schools managing change and re-examining training and their place in the world, the Guildhall is a wonderfully rich mix of the conservative and the cutting edge. For over 30 years it has questioned the orthodoxy of arts training and provoked debate and analysis of the place of the arts in our contemporary world. This attitude has become part of the institution’s DNA, and informs its overall culture.

A key person responsible for this highly developmental approach to higher education is Peter Renshaw (in photo, left, with this writer), whom I first got to know in the early 1980s when he was Principal of the Yehudi Menuhin School in the U.K. He had arrived at the Menuhin School in 1975 having taught philosophy at the University of Leeds Institute of Education and the University of York. He trained as a violinist playing in the National Youth Orchestra and studying at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. But it was his desire to specialize in Philosophy of Education at the University of London and his Master of Philosophy thesis, “A Concept of a College of Education,” which heralded his critical and intellectual approach to every aspect of education and its place in society.

A key person responsible for this highly developmental approach to higher education is Peter Renshaw (in photo, left, with this writer), whom I first got to know in the early 1980s when he was Principal of the Yehudi Menuhin School in the U.K. He had arrived at the Menuhin School in 1975 having taught philosophy at the University of Leeds Institute of Education and the University of York. He trained as a violinist playing in the National Youth Orchestra and studying at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. But it was his desire to specialize in Philosophy of Education at the University of London and his Master of Philosophy thesis, “A Concept of a College of Education,” which heralded his critical and intellectual approach to every aspect of education and its place in society.

At the Menuhin School he changed the culture of training for purely “hot house” instrumentalists by redirecting that talent outward. He encouraged young musicians to interact with a wide swathe of the community, much of it underserved. In so doing, he set the stage for the students to broaden their roles, their responsibility, and understanding as musicians.

Peter moved to the Guildhall in 1984 where he continued to develop this line of thinking and finally retired in 2001 as Head of Research and Development. During his tenure and up to the present day, his teaching, research, and engagement touched the lives of many musicians. Indeed, many new leaders are carrying on his legacy, such as Helena Gaunt, Assistant Principal (Research and Academic Development) at the Guildhall, and Sean Gregory, Director of Creative Learning, Barbican and Guildhall.

But to say he has retired would be so misleading. Since 2001 he has continued his engagement with music training across Europe, writing provocative and stimulating papers, and generally making himself available to anyone and any organization demonstrating a move away from the status quo. At age 77 he is as young and vital in his thinking and firm beliefs as when I first met him all those years ago. He still asks the most difficult questions.

But to say he has retired would be so misleading. Since 2001 he has continued his engagement with music training across Europe, writing provocative and stimulating papers, and generally making himself available to anyone and any organization demonstrating a move away from the status quo. At age 77 he is as young and vital in his thinking and firm beliefs as when I first met him all those years ago. He still asks the most difficult questions.

He has just produced what I consider to be an important provocation paper for the Guildhall entitled Being–in Tune: Seeking ways of addressing isolation and dislocation through engaging in the arts. Its intent is to encourage discussion and debate, to allow us the space, time and opportunity to ask challenging questions about the arts and our responsibilities to society so that we can “respond creatively to the massive changes taking place in society.” This “Provocation” is full of passion, energy, ideas, some frustration and just a smidge of righteous indignation. It also demonstrates an idealism about the power and transformative effects of the arts and how they could be used and developed in our society to a much greater degree than we imagine at the present, and about the place of conservatories in providing training and re-evaluating their priorities and assumptions. Daniel Barenboim is invoked with some of the keen questioning he has been posing: “Classical music is trapped in an ‘ivory tower’ that has become far too specialized — a specialized audience listening to specialized people play. Both have lost a great part of the connection between music and everything else.”

Renshaw calls for a new paradigm to address the key issues confronting learning and development in the arts. He seeks a model that will connect social and artistic imperatives, access and quality, context and excellence, creativity and risk taking, research and professional development. He envisions a paradigm that will create more interconnectedness for the arts in addressing the needs of our rapidly changing world.

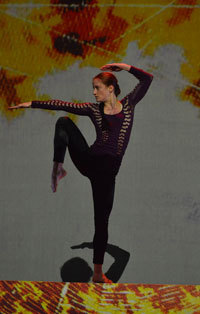

The paper contains some compelling examples successful interconnections based on this paradigm. They include Blue Boy Entertainment (see photos above) based in East London which trains young talent using dance, and Barbican Drum Works also working in East London with young people aged 11-23. Each of these projects demonstrates how the arts strengthen self-esteem and self-respect, and break down feelings of alienation and isolation.

Renshaw feels strongly that conservatories do little to “prepare students and emerging artists for the wide-ranging demands of a work force that is far more differentiated than that of the past. Are the old tried-and-tested models of professional preparation sufficiently flexible and responsive to meet changing needs?” Renshaw invites us to reflect, question, analyze, debate, “to ensure that there is a synergy between the social and the artistic — a synergy that brings with it a sense of dynamism and a confidence in risk-taking.”

I found his paper demanding, provocative, and at times challenging to read. I wanted more context: an analysis of curricula, a study of music and arts in the public school system, research in changing demographics, the place of the major arts institutions, resource allocation. But I suppose such reports exist elsewhere and that’s where I should look. Essentially then, I responded to his concerns for our changing world and society, and the unique contribution that the arts could be making beyond the traditional and historical methods of delivery that we often unquestioningly leave in place. His reflective invitation is to join him for a conversation, open to questions and new thinking in a context of tolerance and intelligence. Who knows where that could take us, but it would be an enthralling conversation to have with his wise and fascinating intellect. And maybe it would help us all in Being — In Tune with our world.

Images of Boy Blue Entertainment’s production of The Five & The Prophecy of Prana by photographer Hugo Glendinning courtesy of the Barbican Centre

No comments yet.

Add your comment