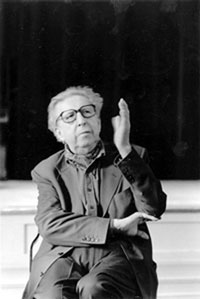

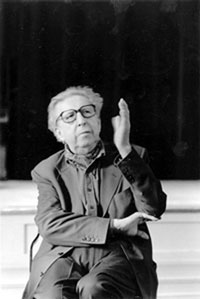

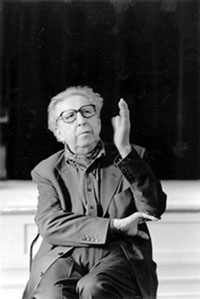

Henri Dutilleux, courtesy of New England Conservatory

Have you ever played that game where someone puts on a piece of music and you have to guess the composer and the work? It’s really fascinating because it brings into play an amazing mixture of intellectual analysis and emotion — the surprise of the unexpected, the Sherlock Holmes-like deductive musical reasoning, and that horrible ego-driven fear that you will look like a fool.

I can remember playing this game in the mid-1970’s with a composer friend of mine, Alan Ridout, who loved acting the Renaissance man and mentor to my eager youth. The work he chose to play, on black vinyl then, was one I had never heard, nor could I identify the composer, but I did hazard the guess that it was a symphony.

Alan seemed surprised that I would come to that conclusion and asked me to explain my thought process. I said that the musical ideas and themes were so strong, so memorable, and had such potential and energy for development that it had to be a symphony. And I was right.

It was the First Symphony (1951) of Henri Dutilleux, a composer who was entirely new to me then. I came to know the work well and it started me along a road of discovery of one of the finest composers of the 20th Century. Not as well known as his contemporary Pierre Boulez, and certainly without the profile of a Stockhausen, or Shostakovich, but in terms of quality and originality, he was one of the greats. When I ran the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra in the U.K. in the 1990’s I championed many of his works and eventually decided to go over to Paris to meet the great man and invite him to be our composer emeritus. This was a very exciting prospect and I wanted to give it my very best shot.

Île de Saint-Louis, courtesy of Creative Commons

Île de Saint-Louis, courtesy of Creative CommonsUnfortunately, the day I chose for this expedition was about the worst of the year as France decided to go on national strike. So no public transport, no trains. I was staying in northern France and, undaunted, rented a car, bought a map, and set off. That was the easy part. Have you ever driven in Paris? Or, more particularly, the infamous

peripherique that surrounds Paris like a poisonous snake? The quality of driving there, particularly on the peripherique, makes Boston drivers look like Sunday school teachers. The map was useless, so I decided to navigate using the beacon of the Eiffel Tower as my geographical point of reference. I had roughly worked out that Dutilleux’s apartment was somewhere to its left. The only upside to the national strike was parking…no police reading meters and no fines. I parked almost carelessly, found my bearings (just three blocks from his apartment), bought des fleurs for Madame Dutilleux and went to find his apartment — on the Île de Saint-Louis, just around the corner from the building where Chopin lived in the 19th Century.

I remember his home being quite small, quiet, beautifully appointed, with discreet pictures and some framed original manuscripts signed by Ravel. Dutilleux was the quintessential Frenchman. Charming, beautifully combed hair, a handsome smile, and an accent which was so like Maurice Chevalier; in fact we spoke together partly in French and partly English. The problem was finding that point of connection, something that would give me the opportunity to extend the invitation to accept an appointment with our orchestra. Long moments wrestling with language, waiting for the espresso to be made, and then I spied a heap of CDs, mostly of Sarah Vaughan. I adore Sarah Vaughan so started my story of discovering this most amazing voice years past. That did it. He was so delighted that we chatted about “Saara…” for ages and then he asked…and I knew I was “in” at this point…whether I would like a “weesky and a gauloise.” Johnny Walker Red Label and a Disque Blue have never tasted so wonderful.

Dutilleux, Courtesy of Creative Commons

Dutilleux, Courtesy of Creative CommonsLunch followed in his favorite restaurant on the Île about which I can only remember that it concluded with a vat of mousse au chocolat being brought and left at our table. And what followed the mousse was a friendship with this most amazing creative genius who gave us the first performance of his revised

Timbres Espace Mouvement, which the Bournemouth Symphony performed with Andrew Litton at the Royal Albert Hall to celebrate our 100th anniversary. Dutilleux’s works became a regular part of our repertoire and included the

Cello Concerto “Tout un monde lointain” which we gave at Carnegie Hall with Lynn Harrell and Yakov Kreizberg. The beauty of this work, the subtleties of its use of instrument (I say this because it is far more than just good orchestration), the “fragrance” of the orchestral sounds, and the singing line of the solo part, are things I return to with amazement and joy.

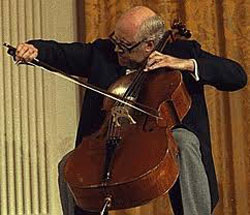

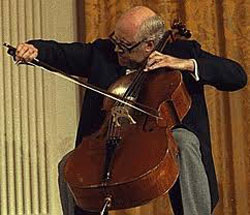

Mstislav Rostropovich, courtesy of Creative Commons

Mstislav Rostropovich, courtesy of Creative CommonsI’ll leave you with an image of the composer in the most social and relaxed of settings, post-concert at dinner with the great Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich (our soloist), Andrew Litton, and… former Prime Minister Sir Edward Heath (my wife and I always think that this line-up sounds like the start of a joke…but it really wasn’t). Picture Slava, whose personality and charisma were like being in front of an open furnace, taking the floor — much wine had circulated all evening, of course — and raising toasts to almost everyone present in the restaurant. Finally, the great cellist turns to Dutilleux with smiles and admiration and says in that inimitable Russian accent of his “but off cos…hee iz ah heenius.” And indeed he was….

No comments yet.

Add your comment