The Longwood Symphony: An Interview with Lisa Wong, M.D.

Ann Drinan: Describe the Longwood Symphony and tell us a bit about its history.

Lisa Wong: The Longwood Symphony (LSO) was established in 1982 to bring together medical professionals, and is dedicated to healing the community through music.

The LSO is the medical orchestra based in Boston’s medical district. It takes its name from Boston’s “Medical Main Street” – Longwood Avenue, home to Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Children’s Hospital Boston, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and the Harvard Medical School.

We have 120 members, and usually about 90 will play a concert. Members of the orchestra come from 27 academic affiliations and 19 institutional affiliations. And we have interesting “crossover” stories: a second violinist sharing a music stand with her medical school professor, or a cellist appointed chief resident for the bassoonist’s medical team.

One of my favorite “crossover” stories involves our first oboist, who was studying for his board exams. He was sitting between a radiation oncologist and a leukemia specialist who does transfusion medicine. During breaks when they weren’t playing, he’d asked the oncologist about the difference between two drugs, or the leukemia specialist about diagnosing different blood smears. Only in a medical orchestra would you find such unique conversations in the wind section!

We rehearse weekly at Boston Latin School, the nation’s oldest public school, and we give four concerts a year at New England Conservatory’s Jordan Hall. We also give a free concert at Boston’s Esplanade Shell on the Charles River in the summer.

AD: How unusual is it to form an orchestra from a medical community?

LW: We are definitely not unique. There are at least 28 such orchestras around the world, including the Albert Einstein Symphony Orchestra, the Australian Doctors Orchestra, the Doctors Orchestra Society of New York, European Doctors Orchestra, l’Orchestre des Medecins de France, Los Angeles Symphony Doctors Orchestra, Musici Medici Orchester in Berlin, and the Orchestra Medicus Japan, to name a few.

And many accomplished musicians have gone to medical school. Conductors Zubin Mehta, Sir Jeffrey Tate and composers Alexander Borodin and Samuel Zyman all graduated from medical school. Accomplished flutist René Laennec used his knowledge of wooden flutes to invent the stethoscope. So medical musicians are not particularly uncommon.

In fact, roughly 75% of people in the medical and scientific community took at least one year of music lessons as kids. The LSO was founded by trumpeter Rev. Dr. Guy Steele and violinist Rev. Charles Kessler, two chaplains at New England Deaconness, following an observation by Rev. Steele that there was a symphony orchestra walking into the medical building every day. So they started asking around and thus was born the “medical orchestra.”

AD: Is there anything unusual about a medical orchestra?

LW: I think performance anxiety is a serious problem for many of our players. Physicians are so used to being in charge, and here they’re presenting a side of themselves or a capability that isn’t as finely-honed as their medical skills. Our bassoonist, Dr. Stephen Wright, became quite interested in the phenomenon from a medical point of view – how does emotion play into gastro-intestinal disturbances, and why are some people crippled by performance anxiety while others find it gives their performance a little extra bit of excitement. Our clarinetist/oncologist, Dr. Mark Gebhardt, summed it up perfectly, “I used to get very nervous before playing a solo, until I realized, one day, that the worst that could come of a flubbed note or missed entrance would be a few moments’ embarrassment. But no one would lose a limb or die. Although I always want to do my best in concert, that thought put it all into perspective.”

AD: Tell me a bit about yourself.

LW: My father grew up in a large family in Honolulu and attended college there, and then took advantage of the GI bill to attend Northwestern Law School. He became a tax attorney, moved back to Hawaii, met and married my mother, and they raised five children. He became the nation’s first Asian-American Federal District Court judge. He was determined to provide all of us with the musical training that his family couldn’t afford to give to him. So we have three violinists, a cellist, and a trumpet player (my younger brother) in the family.

I attended Punahou School in Hawaii a few years ahead of Barack Obama, although I didn’t know him then. While in high school, I volunteered at the Shriners Hospital for Crippled Children, which had many young patients from the Polynesian Islands. I became aware of how homesick they all were, as they were treated over several weeks or longer for a genetic orthopedic problem common to Polynesians, so I began bringing music to them. The music would make them smile and forget their pain and homesickness for a while.

After high school, I attended Harvard, where I lived in the same dorm as my future husband, Lynn Chang, cellist Yo-Yo Ma, and pianist Richard Kogan – these three are still making music together all these many years later. My experiences at the Shriners Hospital had been very powerful, and I knew that I wanted to work with children, so I went to NYU Medical School to become a pediatrician. While there, I helped found the NYU Chamber Music Society, so I never stopped playing. I moved back to Boston to marry Lynn and complete my medical training. I am now a pediatrician with Milton Pediatrics and an assistant clinical professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School. And I was President of the Longwood Symphony from 1991 until 2012, and play violin and viola with them.

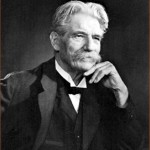

AD: You spoke at length about Albert Schweitzer at your presentation in Hartford.

LW: Yes, he’s a particular hero of mine, the greatest of all musician-physicians. Indeed, Dr. Schweitzer won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1952. He was a theologian and professional musician in Alsace, and received a Ph.D. in philosophy. At the age of 30, he learned of the primitive state of medical care in sub-Saharan Africa, so he went to medical school and moved to the village of Lambaréné in Gabon. He developed a spiritual practice called the Reverence for Life and devoted his life to his patients in Lambaréné. His life and work have profoundly inspired me and most of my colleagues in the LSO.

AD: What do practitioners of the healing arts of music and medicine have in common?

LW: A shared dedication to excellence, innovation, attention to detail, creativity and empathy. A lifetime spent seeking ways to elevate humanity.

AD: You brought up quite a few comparisons between studying to be a doctor and studying to be a musician. Can you summarize a few of these points?

LW: Both courses of study have three components: learning the basics, adapting to the world around you, and becoming part of the community.

- Learning the basics means hard science in medicine, and scales, arpeggios and theory in music.

- Adapting to the world around you means patient care, and research for and with others in medicine, and performances, ensembles, and orchestras – playing music with and for others in music.

- Becoming part of the community means research with clinical correlation, public health, and information sharing in medicine, and audience and community engagement, and playing to make a difference in music.

AD: During the event in Hartford, you introduced me to Frank Davidoff, M.D., former editor of the Annals of Internal Medicine, who published an article about what musicians can teach physicians. Thank you for that introduction – I wrote a Polyphonic blog post about his article.

LW: I found Frank’s article online and contacted him. His daughter is the librarian for the Hartford Medical Society – it was through this connection that I was invited to give a lecture in Hartford.

AD: How can an orchestra of medical professionals make a difference in the community?

LW: Let me answer that with a quote from Dr. Schweitzer: “The only ones among you who will be truly happy are those who have sought and found a way to serve.”

The mission of Longwood Symphony Orchestra is to perform concerts of musical diversity and excellence while supporting health-related nonprofit organizations through public performances.

We have three unique programs that impact the community in three different ways.

AD: Let’s take them one by one. The first one has you partnering with a nonprofit health-related organization.

LW: Yes, the Healing Art of Music program is a true collaboration between the orchestra and the partnering community organization, in an ongoing, long-term collaboration that empowers each organization and promotes self-sufficiency. LSO guides each organization to use the concert as a centerpiece of a unique fundraising event.

This program was an outgrowth of a symposium we did in 1991 with Yo-Yo Ma to celebrate Dr. Schweitzer’s Reverence for Life philosophy. It was a two-day event, with community leaders taking over public spaces to consider public health challenges such as HIV/AIDS, domestic violence, and homelessness. It culminated in the concert on the second day, with the doctors and staff of many organizations attending. We had also given out tickets to many clinics to pass out to their patients and clients. During the concert, we realized that there were many empty seats in the hall and suddenly realized that homeless clients couldn’t come because the shelters close at 10, victims of domestic violence wouldn’t attend a public performance for fear of personal safety, etc. Those empty seats resonated with us, and we resolved to do something about the people who should have been sitting there with us. Thus was born the LSO Healing Art of Music program, a program where we raise awareness and funds for organizations that care for the medically-underserved.

AD: Explain the details of how you partner with a non-profit.

LW: Our partner invests in the program with us by buying a block of tickets, about 1/3 of the house. Then we work together in putting it together: how to publicize the concert, how to connect with the media, and how to create radio spots and a tag line. We give them the opportunity to reach out beyond music critics to healthcare reporters and regional city editors for publicity.

AD: Name a few of your partner organizations.

LW: Over the past 20 years, the LSO has worked with 40 organizations, including community health centers, social service agencies, research programs, and arts and healing organizations, and we’ve raised over $1 million for healthcare non-profits. A few of our partners include Artists for Alzheimer’s, the Boston Healthcare for the Homeless program, the Shriners Burn Hospital, and the Mattapan Community Health Center.

AD: You told a very moving story about a young Korean teenager, both in your book and at the presentation. Tell us about him.

LW: Jonathan is Korean by birth and was adopted by an American family in Massachusetts. The family has two biological daughters and two adopted Korean children. He came to my office in 1989 with puzzling bruises on his legs and arms.

He had just graduated from high school and planned to attend Babson College. Instead, he spent most of his next two years at Children’s Hospital – the tests I ordered for him resulted in a diagnosis of leukemia – a form of leukemia that became progressively more resistant to chemotherapy. His two college-aged sisters began organizing bone marrow drives on college campuses across the country. The family found his biological brother living in Switzerland – he came to the US to be tested, but he too was not a match.

The LSO stepped in and partnered with the National Marrow Donor Program at its next concert; we raised awareness throughout greater Boston about the National Bone Marrow Registry. The funds raised by the concert enabled Jonathan’s sisters to organize five more bone marrow drives on campuses, which grew the Asian bone marrow registry numbers from 3,000 to over 11,000.

And Jonathan did finally find a match – his biological mother in Korea. The adoption agency had kept excellent records and was able to locate her. She gave him life for a second time through a successful bone marrow transplant, and a close relationship has developed among Jonathan, his birth mother, and his American family.

AD: The LSO also has a program that sends chamber ensembles into medical facilities throughout greater Boston.

LW: A few years ago, the LSO started “LSO on Call,” where small ensembles perform in hospitals and other patient care facilities. LSO chamber groups perform in at least one healthcare venue every month, bringing music directly to patients. One day, October 17, 2009, was particularly memorable – we had reserved that date for a morning dress rehearsal and afternoon concert, but our conductor was unable to make the date. So we decided to perform anyway, so 58 LSO musicians formed 14 chamber ensembles and performed in 21 healthcare venues across Massachusetts for 800 patients, with most ensembles giving two performances, morning and afternoon, on that date. We were coached by professionals about how to give a presentation/performance to patients.

AD: You described the experience of a string quartet performing in an Alzheimer’s unit, and each member of the quartet has a family member living with Alzheimer’s.

LW: The quartet went to a nursing home to play for Alzheimer’s patients, some of whom hadn’t spoken in months, or even years. They started with Mozart, and then moved on to show tunes. Suddenly the audience who couldn’t communicate started singing and clapping; they remembered all the words from memory. This experience was extremely moving for the members of the quartet, who all had a personal connection with Alzheimer’s, and to the caregivers and nursing staff.

Another ensemble had the experience of playing at a psychiatric hospital for several patients with severe psychotic illness. One patient would chronically either rebuke the caregivers angrily, or ignore them. She came to the performance, sat and listened calmly, and then she thanked the medical musicians for their music. I think this patient was particularly moved because her clinicians were doing something special for her.

Following the performance, a psychiatry resident and violinist said: I’ve played small ensembles at healthcare settings before, but today’s performances were moving to me in a way I haven’t felt before. The experience of performing now for those individuals as a physician as opposed to an undergraduate was deeply powerful. I felt I was touching their lives in a very different but somehow related way. This was such a privilege.”

AD: You told another very moving story about violinist Augustin Hadelich.

LW: Augustin was an extremely gifted violinist who was concertizing in Italy by the age of seven. When he was 15, he suffered severe burns to his face, upper chest and arms in a fire at his home in Tuscany. Fortunately his left hand was spared, but his right arm was severely scarred. The doctors told him he would never play again, but he refused to accept that verdict.

His face and arms still bear the scars from his burns, but his violin playing has excelled, through sheer determination. He enrolled at Juilliard to work on his Artist Diploma, and was a Gold Medalist at the 2006 International Violin Competition of Indianapolis.

Augustin was engaged to play the Glazunov Violin Concerto with the LSO in April 2007; our partner for that concert happened to be the Shriners Hospital for Children, a top pediatric burn center. I asked him if he would play for the children at the hospital – he hesitated, which is understandable, given the deep memories he had of his own time in a burn hospital. But he finally agreed.

I will never forget the flash of recognition in the eyes of those children when Augustin entered the room where the children, in wheelchairs and beds, were assembled. Albert Schweitzer’s words came to mind: “The fellowship of those who bear the mark of pain,” I thought. Without a word, he took out his violin and simply played Bach. Afterwards, he took questions. A teenage girl asked him in Spanish, “How did you do it? How did you leave here? What did you think about to get better?” He answered her in Spanish, “Imagine yourself already out of here. Think of what you want to be doing after your time here, and aim to go there.” I could see from the glow in the girl’s eyes that she understood.

AD: Perhaps the story that affected me the most is what you call “The Ballad of Ruth.” Tell us about how music changed her life.

LW: Ruth had fallen and broken her hip; she was in a dementia unit and seemed to have completely lost her memories and, with them, her “self.” She always seemed to be asleep in her chair. She didn’t respond to physical therapy. Occupational therapist Tamara Goldstein tried putting cold water on her face, calling to her, talking to her. She responded to nothing. One day Tamara turned on Boston’s classical music station, WCRB, and told Ruth that she played violin in the Longwood Symphony. Ruth opened her eyes, looked at Tamara, and said, “My husband was a composer.” It was the first thing she’d spoken in months, if not years.

Tamara asked Ruth if she liked music and she replied that she was an opera major at the New England Conservatory and proceeded to sing. Ruth became a changed woman – she began walking and smiling. It was as though music had turned on a switch in her – she began participating in simple activities and smiling as she did so. According to Tamara, “It felt like a miracle.” It’s quite possible that the music was the right kind of connection that stimulated interest in something meaningful from her past, and awakened neuro-pathways and neuro-chemicals that aroused her to consciousness.

AD: That’s such a wonderful story. What is the third type of program the LSO presents?

LW: The LSO Community Conversations. For example, in 2011 we held a symposium on music, neuroscience, and healing called “Crossing the Corpus Callosum: Neuroscience, Healing and the Arts” that brings scientists, doctors, musicians and therapists together. One of the speakers we invited was performer and composer Arthur Bloom, who spoke about his work with severely injured Iraq War veterans through a program he calls Musicorps. Professional musicians work with the veterans to confront their anger and pain through performance and song-writing. The music helps them explore and release emotions, thus helping them to cope with their PTSD symptoms.

Our third symposium is in partnership with Lesley University, Boston Arts Consortium for Health (BACH), Berklee College of Music, Harvard Medical School, the New England Conservatory of Music, and the LSO. Held November 30/December 1, 2012, it covers such thought-provoking topics as Healing by Design, Arts in the Global Community, Music and Healing, and Arts in the CommonHealth, including thoughts about universal design for the arts.

AD: In closing, you charged the physicians in attendance at your talk to find inspiration from today’s examples to integrate the healing arts in their own daily practice.

LW: We have devoted our lives to healing our community. Over the past century medical discoveries and technology have eradicated many diseases, improved quality of life, and increased life expectancy. But there are limits to what medical technology can do. As doctors, we need to return to our medical roots. Our musical training helps us to listen, not just hear, and to recognize that there is a song in every diagnosis.

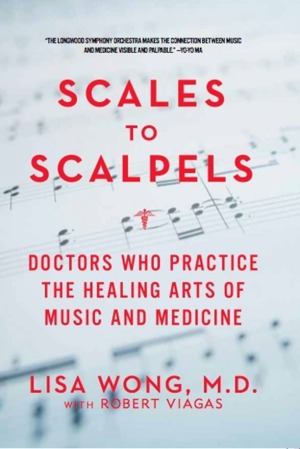

Editor’s Note: You can find out much more about Dr. Lisa Wong, her book Scales to Scalpels, and the Longwood Symphony by visiting her website.

[…] recommend not only my article, which interviews Lisa about her book and the work of the Longwood Symphony, but her book, Scales […]