Guest Blogger: Joseph Swensen

“Violinist/conductor Joseph Swensen is the Founder and Artistic Director of U-HAC International; Principal Guest Conductor and Artistic Advisor of Ensemble Orchestral de Paris; and Conductor Emeritus, Scottish Chamber Orchestra. As a violinist he has recorded the Beethoven Violin Concerto with Andre Previn and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, the Bach Sonatas with NEC’s very own keyboardist John Gibbons, and the Sibelius Violin Concerto. As conductor and violinist, he has recorded concertos and orchestral works by Mendelssohn, Prokofiev and Brahms with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra. My first encounter with him was while I was running the Bournemouth Symphony and Joey came to play the Beethoven Concerto. His was a performance of great musical integrity and originality. After that occasion, I gave him some of his first conducting opportunities. I’m delighted to have him write a guest blog on a subject that I know is of passionate concern to him.” –Tony Woodcock

UNIFORMITY, ENTITLEMENT AND SOMETHING CALLED U-HAC

When I was a child, Stravinsky, Copland and Shostakovich were the living legends, the heroes, the artistic giants clearly at the top of the classical music hierarchy. The gradual “flattening out” of that hierarchy during the decades since, has had a profound effect on the world of classical music. Don’t get me wrong, I am no advocate of the return of the old hierarchy, but our community needs to become more idealistic from the bottom up. Specifically by way of the education of future generations of classical artists.

Pragmatic goals now dominate the minds of many an artist, and a valid and earnest concern for the survival of the massive artistic institutions our forefathers built is justifiable, if self-serving. These institutions span the globe and require thousands of professional musicians to fill the positions they have created. Competition for these positions is fierce and salaries are usually very good. This competition, although seemingly necessary and certainly practical, has lead inevitably to an unprecedented uniformity and orthodoxy, even among many composers. This orthodoxy has ironically and tragically resulted in what seems to me to be the near renunciation of a previously shared conviction: that the most important factor in all artistic creation is the expression of what could be called the unique, mystical center within every artist, namely the soul. Of the soul, Johannes Brahms in the year 1896 allegedly said: “the soul of man is not conscious of its powers…to evolve and grow, man must learn how to use and develop his own soul forces (sic).”(1)

In classical music training, separating the art from the craft is widely considered an essential part of the education. My violin teacher, Dorothy DeLay, was a pioneer and a revolutionary in taking this idea to the extreme. She and others like her taught us to systematically separate all technical aspects of playing an instrument from the integrated organic whole for the sake of perfecting the craft of music making, assuming the art (and soul) would take care of itself. She explained to me when I was fourteen years old that the reason she never mentioned the intangible or mystical aspects of music in her teaching was that she simply didn’t know how to speak about things she could not quantify. I remember being relieved however when she admitted to me that she nevertheless accepted these aspects of art as essential. But I complained to her nevertheless that, by choosing not to speak of the mysterious and intangible, she was giving the world the mistaken impression that she herself didn’t believe that they were important or that they even existed at all!

The musical values of our time were also deeply influenced by Igor Stravinsky. Famous for his disrespect for and dislike of performing artists, (especially orchestral musicians whom he often referred to as “nitwits”), Stravinsky demanded an unprecedented level of objective literalism in the performance of his works. In 1947 he wrote: “Interpretation is at the root of all the errors, all the sins, all the misunderstandings that interpose themselves between the musical work and the listener and prevent a faithful transmission of its message”(2) Perhaps this and other similar outbursts on the subject by Mr. Stravinsky are understandable overreactions to the irresponsible and arbitrary freedoms some mediocre early 20th century players exerted over composers’ apparent intentions.

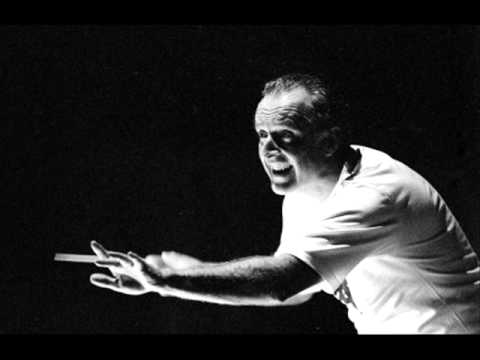

It is clear to me that it is the misunderstanding and misuse of DeLay’s and Stravinsky’s philosophies, which have become the conventional wisdom in classical music today. Consequently, a new ideal has emerged: the ideal of uniformity. For example, a good string quartet is considered to be one in which the members’ sound, phrasing and intonation is indistinguishable one from the other. Decisions concerning uniform bowings in string chamber groups are often the first and sometimes the only discussion in rehearsals. As long as we all uniformly follow Stravinsky’s admonitions, we needn’t do anything as musicians other than robotically reproduce literally what the composer wrote on the page. Almost all “good” symphony orchestras are on ”uniform and blended” mode, (and many of the most prestigious ones are by far the most uniform). Conductors have little long-term influence. Even the great Carlos Kleiber, who famously referred to the Berlin Philharmonic as “wall to wall carpeting” in the 1980′s was, in my opinion, no match at the end of the day for the power of that orchestra’s uniformity ideal.

Beethoven : Coriolan – op.62, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Carlos Kleiber

Live Recording from 28 June , 1994 ;

All this uniformity and conformity obviously leave little room for anything Brahms might have called “soul work”, or in other words, art.

I don’t know about you, but this reminds me more of a military paradigm than an artistic one. Could this mentality be the legacy of classical music’s most influential conductors? From well before Toscanini to Solti and von Karajan these conductors taught us to be exacting, uncompromising soldiers. Even now, years after the last of them has gone, we continue their work by tyrannizing each other and ourselves. Georg Solti once said, when predicting the bright future of a promising assistant: “good sergeants make good generals!” It is ironic that since the Second World War, the world has become more free and diverse, while classical music has become more regimented and uniform. This ideal of uniformity is being passed on by way of most of our educational institutions for a very good reason, the job market requires it, and we believe that we are powerless to change the values of that market. I protest. We must change those values and it is the educational institutions themselves that need to lead the way to a more inspiring and interesting future for classical music. We educators need to implore young artists to have the courage to be true to their unique souls and see themselves as part of a force for positive change, from the bottom, up. This is imperative, not only for the sake of our finding joy in music once again, but for our very survival.

I dream of a more colorful, creative and relevant classical music world and I am not alone in pursuing this dream. Great work on behalf of these ideals is being done by extraordinary people all over the world and along with my partner Victoria Eisen, I am pleased to join their ranks with the creation of a new kind of arts education and arts aid organization: Unity Hills Arts Centers International (otherwise known as U-HAC International).

U-HAC’s home-base, a historic, inspiring 15-room, circa 1776 farmhouse in Townshend, Vermont, USA, is a meeting, learning, working and living space for artists, both professional and amateur.

Here we will continue to bring together artists of all mediums and from all cultural traditions for workshops, regularly occurring seminars, and residencies. We at U-HAC want to teach, learn, work and live with the arts in a completely different way: where inspired improvisation is the absolute ideal, the starting and ending point of all great art and all real living, where the “beginners mind” of the amateur and young student is at least as highly valued as the convictions and sophistication of the professional (the term “beginners mind”, used by the Buddhists, describes the state of mind in which one feels that everything is possible), and where teaching and learning are two sides of the same process shared by all involved.

We in the classical music world need to start to think differently, we need to set out to break the mold of uniformity. (Uniformity being obviously the absolute antithesis of “beginners mind”). It is that mold of uniformity itself, which is preventing innovation, individualism, artistic freedom and for some, real joy from becoming once again a part of the professional classical musician’s daily life. Although we may be created equal, we are not meant to become uniform. This is symbolized at the U-HAC home base by the power and infinite variety of the natural surroundings.

Music making should be a personally, uniquely transformative experience for MUSICIANS, not just for the music-loving, paying public. I was therefore pleased when, after our recent August 2011 seminar, ”Total Immersion in Brahms and Bach”, which brought together instrumentalists, conductors, composers, scholars, writers, visual and culinary artists of all ages, levels and cultures, many participants called it ”a completely life-changing experience.” Our sincere hope is that everyone who spends time at U-HAC will, each in his own way, take what he experienced back into the world, sharing these fresh values with colleagues and demanding them from leaders.

Complementing our work at the home base are the U-HAC Satellites. These mobile buildings, which will be constructed from recycled materials, will be sent to underprivileged and underserved rural communities worldwide. Village life across the world is fast disappearing as more and more young people from villages seek a more prosperous life in the cities. The social, cultural, economic and ecological results of this are disastrous and U-HAC wants to play a positive role by helping to enhance the cultural life and therefore the quality of life in the world’s villages. Each of these U-HAC Satellites will offer a varied curriculum of workshops in the arts of all cultures and each will present its own world-class concert series. They will be staffed in part by a kind of ”peace corps” of dedicated artist volunteers who believe that the arts can be a powerful means for social and economic revitalization. Most importantly, all U-HAC endeavors will be carried out with the utmost care for the earth’s natural environment.

Other projects in various stages of development are the U-HAC Mentor/Apprentice Orchestral Institute, a program where orchestras will be created with one half retired professional orchestral musicians and the other half young students, sitting alongside each other for intensive workshops in orchestral playing. These workshops will take place in rural villages worldwide providing orchestral concerts for those communities in addition to providing profound benefits for the participants. The U-HAC Chamber Players, the resident ensemble at the home base and at all the U-HAC Satellites, is an ever-evolving group of about a dozen musicians which provides an invaluable, educational stepping stone in the form of performance and touring opportunities for the most accomplished and promising young artists at the very beginning of their professional careers.

Combining the vertical climb towards the highest imaginable artistic ideals with the corresponding horizontal outreach to humanity at large is the greatest challenge of the artist of today. We classical musicians have been indoctrinated with the belief that, solely due to the high art we create, we are indispensable to humanity. Like the monks of old, many among us presume that other people should finance our quest. This culture of entitlement contributed to the disappearance of most of the world’s monasteries and we classical musicians must avoid the same fate. If UNICEF provides food, and Doctors Without Borders provides medicine, we artists must create more aid organizations that provide the arts to the needy. No man should live by bread (or meds) alone and the arts are an essential nutrient for the survival of the human race.

In the USA, where the vast majority of public schools no longer even offer music in their curriculum, U-HAC International is one small organization, still in its infancy, yet full of hope, enthusiasm and energy. We are attempting to fill a void, and eager to play a role in the coming rebirth of a new and rejuvenated arts world.

(1) Arthur M. Abell, “Talks with Great Composers” (New York, N.Y.: Citadel Press, 1994) 6-7

(2) Igor Stravinsky, “Poetics of Music in the Form of Six Lessons” (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1947), 122-3