Lincoln Portrait and the Fourth of July

Copland’s Lincoln Portrait is not terribly popular with orchestra musicians, mostly (I suspect) as a result of over-exposure to bad performances. It invariably gets scheduled on pops programs and outdoor concerts, usually with the lowest-ranking staff conductor who’s in town at the time, and generally with narrators chosen more for who they are rather than how they can actually … narrate. (The list of those who have narrated the work is both long and strange; it includes Hugh Downs, Katherine Hepburn, Margaret Thatcher, Willie Stargell, and Julius Erving.)

The story of how Copland’s most popular work came to be is worth recounting. A few weeks after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the conductor Andre Kostelanetz (who, among other achievements, virtually originated the genre of “easy listening”) commissioned Jerome Kern, Virgil Thomson, and Aaron Copland to write musical portraits of “eminent Americans.” Kern wrote Portrait for Orchestra (Mark Twain) and Thomson wrote musical portraits of both Fiorello La Guardia and Dorothy Thompson. Copland originally proposed Walt Whitman, but Kostelanetz expressed reluctance about commissioning two portraits of writers, so Copland went on to Lincoln – who was not even on Kostelanetz’s proposed list of subjects. (Thomson reportedly advised Copland against Lincoln on the grounds that Lincoln was too big a subject for Copland to be able to do justice to. Copland himself was skeptical of the whole project, writing at one point “I had no great love for musical portraiture… and I was skeptical about expressing patriotism in music—it is difficult to achieve without becoming maudlin or bombastic, or both.”) All three works were performed for the first time by the Cincinnati Symphony on May 14, 1942.

So why did Lincoln Portrait become a staple of the outdoor orchestral repertoire, while Kern’s and Thomson’s efforts vanished into obscurity? No doubt the fact that only Copland chose to feature narration helped. Lincoln was the finest writer of political prose in American history; his only rivals in the Anglosphere are a bare handful of English statesmen (including, of course, Winston Churchill). Lincoln’s words are very stirring all on their own. But Copland’s music, while not his very best, is still first-rate: a solid and beautifully-crafted example of his “wide-open prairie” style that captures the melancholy and tragedy that surround both the reality and the myth of Abraham Lincoln.

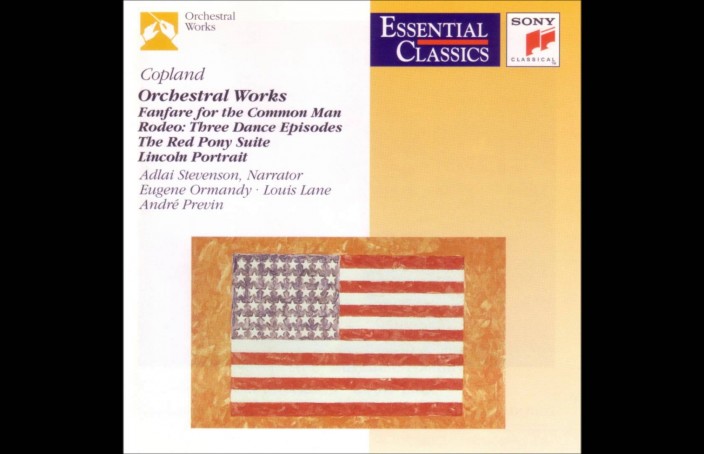

I was lucky enough to grow up with a great recording of Lincoln Portrait long before I was over-exposed to bad performances. In 1964, the Philadelphia Orchestra and Eugene Ormandy recorded the work with Adlai Stevenson, a name not well-remembered today, but a former Governor of Illinois, two-time Democratic nominee for the Presidency, and John F. Kennedy’s UN ambassador. More relevant to his role as Lincoln Portrait narrator was his descent from a long line of Illinois politicians, one of whom was Lincoln’s campaign manager during his 1858 Senate run.

Whatever the reason and the background, the end result was a narration of unsurpassed calm, dignity, and lack of pretension. If you have been subjected, over this or past Fourth of July weekends, to some local celebrity’s attempt to endow Lincoln’s words with “character” or “drama” or other form of excess, you will feel cleansed by listening to Stevenson’s version (start at 7’45” here).

This Fourth of July, Lincoln Portrait is more relevant than ever. Copland, of course, was gay – not something he kept secret from his friends, but one he did not make public. As well as being the normal choice for LGBT persons in the cultural mainstream through much of the 20th century, this also turned out to be a very wise decision in light of his being targeted for his political views by both the FBI and the House Un-American Activities Committee. I suspect that Copland never imagined that the country he knew might someday become one in which the concept of “freedom” would include the freedom for him to marry someone he loved. On the other hand, he might have been deeply disappointed to learn that the Civil War and the system of slavery and racial discrimination that was its cause still resonated so deeply with so many Americans, 150 years after the end of American slavery and 75 years after he quoted from Lincoln’s great prose.

As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy. Whatever differs from this, to the extent of the difference, is no democracy. – Abraham Lincoln, 1858

Robert,

Very nicely written. More often than not, the narrator part – as you mention – seems to be an afterthought and, as you have noted, marketing ploy or political bone. Which is unfortunate since the words are very moving and powerful – as equal and important as the music itself. Thanks for posting. Dileep

Robert writes a lovely tribute to Aaron Copland’s piece, which has indeed been performed in so many places. When listened to appropriately, it is a very moving composition indeed.

But I must share a story. Back in the early 1970s, I worked for SummerThing, a program in the city of Boston that brought the arts to people all throughout Boston. The culmination was a concert at the Hatch Shell on the Esplanade, and they asked my uncle, Fr. Robert Drinan, S.J., a newly-elected Congressman from Massachusetts and a Jesuit priest, to narrate Lincoln Portrait. Bob played clarinet as a kid, and was very eager to do this.

Half-way through the performance, we got “streaked” (for you young’uns, this means a naked person running through the crowd). Bob turned to look at me in the viola section, totally freaked, question all over his face. I gesticulated and mouthed, “KEEP GOING!” and somehow we brought it all to conclusion. It was really too funny then, and when I recounted the story to my colleagues a few months ago when we played “Lincoln Portrait” on a kiddy concert, discovered that it’s still pretty funny!