Commencement Into This New World

May is the season of Commencements and as New England Conservatory and other schools of music prepare to graduate a new class of wonderfully gifted, creative, and idealistic young musicians, one can’t help but contemplate the world in which they will make their way.

May is the season of Commencements and as New England Conservatory and other schools of music prepare to graduate a new class of wonderfully gifted, creative, and idealistic young musicians, one can’t help but contemplate the world in which they will make their way.

For music and the arts in general, we are living out the famous Chinese curse: these are “interesting times.” (Well, yes, we do know that the phrase is not really Chinese. Nor is it a curse. Nor is harm or danger intended by it. Click here for more on that. ) There is clearly turbulence in the education and arts world, although there are different opinions about what that means. Some would say we are at an inflection point in our evolution. Others, more Panglossian, might suggest that all is well with our orthodox approach to the arts and education and the world in general. Still others might suggest that we need a massive revolution to stir the pot and take us out of our complacency.

As I look at the world our students will enter, I recognize both huge problems but also a giant opportunity to put our energetic arms around the issues and do something about them. Indeed, we must do this. This is our world after all and we are responsible for what happens now and for the future.

I have always considered education as a given in our society. Something that is prized as a priority supporting the essential upward trajectory of our world and, at its very best, available to all. But that view is up for debate these days with the value of liberal arts education, in particular, being questioned and the cost of education putting it beyond the means of ordinary people.

The emphasis is very much upon families with resources and the technical side of education that promises an immediate return on tuition investment. The so called STEM curricula: science, technology, engineering and math, are now considered the gold standard. By contrast, the arts are clearly not valued–at least in certain quarters. Which leads us to ask: are we looking at a purely technocratic world for the future, one that is easily understood in engineering or scientific terms but whose creative essence is lost in an equation somewhere?

The emphasis is very much upon families with resources and the technical side of education that promises an immediate return on tuition investment. The so called STEM curricula: science, technology, engineering and math, are now considered the gold standard. By contrast, the arts are clearly not valued–at least in certain quarters. Which leads us to ask: are we looking at a purely technocratic world for the future, one that is easily understood in engineering or scientific terms but whose creative essence is lost in an equation somewhere?

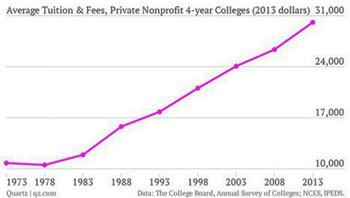

Just as contentious is the cost of education, an issue that seems to be brewing up a storm on a global basis. Having spiraled over recent years (see graph), annual tuition in the U.S. is typically in the region of $50,000. This has resulted in what is often referred to as the “scholarship arms race,” with various institutions competing for the best students with the best possible discount rate. And this, in turn, has placed even greater strain upon colleges’ campaigns to raise money for endowment funds. In Europe, which has traditionally subsidized higher education at 100%, governments are cutting back; the UK, for example, is now charging £9,000 annually. Only countries like Germany and Norway still offer full tuition discount, but for how long is to be questioned. Does this portend a draconian shift of policies, new curriculum priorities, and escalating personal costs?

Just as contentious is the cost of education, an issue that seems to be brewing up a storm on a global basis. Having spiraled over recent years (see graph), annual tuition in the U.S. is typically in the region of $50,000. This has resulted in what is often referred to as the “scholarship arms race,” with various institutions competing for the best students with the best possible discount rate. And this, in turn, has placed even greater strain upon colleges’ campaigns to raise money for endowment funds. In Europe, which has traditionally subsidized higher education at 100%, governments are cutting back; the UK, for example, is now charging £9,000 annually. Only countries like Germany and Norway still offer full tuition discount, but for how long is to be questioned. Does this portend a draconian shift of policies, new curriculum priorities, and escalating personal costs?

Within this Darwinian analysis of higher education, what is the state of play in the performing arts and where exactly is their place in our contemporary world?

The performing arts tend to be highly conservative and resistant to change, which makes them vulnerable and often weak. As someone once said, failure is not fatal, but failure to change can be fatal, and we have seen this played out across the U.S. in recent years. Numerous opera companies and orchestras have gone out of business or are operating with drastic reductions in budget, output and personnel.  Those that have survived–like the Detroit and Minnesota orchestras–are slowly recovering from debilitating internecine warfare. Such crises usually ignite a cauldron of blaming and shaming instead of collaboration and partnering. Yet this is exactly where opportunity can surface and creative, flexible minds can envision a new course far more relevant to contemporary society. That’s not to say that we should dumb down the arts. Far from it. It’s about preserving what we love while building the new relationships and establishing the new priorities we need now.

Those that have survived–like the Detroit and Minnesota orchestras–are slowly recovering from debilitating internecine warfare. Such crises usually ignite a cauldron of blaming and shaming instead of collaboration and partnering. Yet this is exactly where opportunity can surface and creative, flexible minds can envision a new course far more relevant to contemporary society. That’s not to say that we should dumb down the arts. Far from it. It’s about preserving what we love while building the new relationships and establishing the new priorities we need now.

The arts really are among the most powerful forces in our culture. Access to the arts and a meaningful interactive experience should be the birthright of all, not merely the highly educated elite. This is a basic tenet I think we would all defend. Nonetheless, there is dissonance between this tenet and the current arts delivery system, which has buried itself too often in tradition and reliance upon accepted relationships. We need to be striving for the full democratization of the arts which would redefine and sustain its legitimate place in society and move it away from the periphery and into the center.

Our agenda for the future should be about bringing all the elements together: a changing world, the arts’ place in that world, the need for a training and educational program which are reflective of all these needs, and arts and education leaders who have the thoughtful insights and courage that make change happen at all levels. This would involve how resources are used, how we plan, where the relationships are, who the audiences should be, and, most significantly, what the role of artists should be in the C21. (See an interesting article on this subject.)

Such a thorough reassessment is a daunting prospect. Many artists might be tempted to throw up their hands in despair. They could understandably claim that they didn’t go into the arts or music or the theater or dance for that kind of job. They would rather just perform, realize their passion. Well, they can do all these things but with a different understanding of what is needed. Traditional forms of employment–never plentiful–are melting away. Getting a permanent job where a company or institution look after you, pay you a regular salary, and offer healthcare benefits and generous pensions has never been more difficult. And it’s not because artists aren’t good enough but because the economic landscape is changing, and we need organizations and training programs that will take all this into account. Then, when we enter the professional world, we can devise some models of good practice, or continue with research and development. But what is clear is that the artist’s mission must be to strive and reflect and respond in partnership with society as a whole, not as a small element in its elite wing of entertainment and prestige.

Such a thorough reassessment is a daunting prospect. Many artists might be tempted to throw up their hands in despair. They could understandably claim that they didn’t go into the arts or music or the theater or dance for that kind of job. They would rather just perform, realize their passion. Well, they can do all these things but with a different understanding of what is needed. Traditional forms of employment–never plentiful–are melting away. Getting a permanent job where a company or institution look after you, pay you a regular salary, and offer healthcare benefits and generous pensions has never been more difficult. And it’s not because artists aren’t good enough but because the economic landscape is changing, and we need organizations and training programs that will take all this into account. Then, when we enter the professional world, we can devise some models of good practice, or continue with research and development. But what is clear is that the artist’s mission must be to strive and reflect and respond in partnership with society as a whole, not as a small element in its elite wing of entertainment and prestige.

No comments yet.

Add your comment