Benjamin Franklin and the Reflective Conservatoire

I recently heard a mordantly humorous new take on Benjamin Franklin’s most famous quote: “In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes and the immutability of conservatoires.” I was at a major conference at London’s Guildhall School of Music & Drama called appropriately enough, “The Reflective Conservatoire: Creativity and Changing Cultures.” That reworking of Franklin’s quote was part of the opening salvo by David Myers from the University of Minnesota and his group of radical thinkers, who have issued a revolutionary manifesto for the College Music Society, a venerable music education consortium with a name that suggests some sort of glee club. But more of David and his merry band in a bit because I want to begin by painting a picture of what this conference was all about and why it’s important.

First off, this triennial event is much more than a conference. Conferences tend to be for managers with their Power Point slides and late night carousing. This one is different because it brings together practitioners and researchers into dialogue with managers so that information and ideas and new thinking can be shared around an agenda of renewal and innovation.

The spirit of the Conference is very inclusive and energized as it allows all sorts of major issues to surface, as well as the byways of research and new practice to be shared and valued. And the approach is to accept all comers in terms of ideas into the tent. It began in 2006 as the brainchild of Helena Gaunt, the young and very dynamic Vice Principal and Director of Academic Affairs at the Guildhall (in photo right). Hers is a key position and one that has allowed the Guildhall to stake out a unique place in the European Conservatoire network as a cauldron of cutting edge thinkers and practitioners.

The spirit of the Conference is very inclusive and energized as it allows all sorts of major issues to surface, as well as the byways of research and new practice to be shared and valued. And the approach is to accept all comers in terms of ideas into the tent. It began in 2006 as the brainchild of Helena Gaunt, the young and very dynamic Vice Principal and Director of Academic Affairs at the Guildhall (in photo right). Hers is a key position and one that has allowed the Guildhall to stake out a unique place in the European Conservatoire network as a cauldron of cutting edge thinkers and practitioners.

Helena was a professional oboist with the Britten Sinfonia and other ensembles, and has worked closely with new thinkers such as Peter Renshaw. I would describe her work as the Research and Development engine of the Guildhall approach to education, and it’s beginning to yield very positive results. Take for example, the new Guildhall Creative Entrepreneurs programme which was launched in partnership with the charitable fundraising/ development consultancy, Cause 4, which in turn is led by Michelle Wright herself a Guildhall alumna. This project offers the beginnings of a virtuous circle of training, support and development within just one conservatoire.

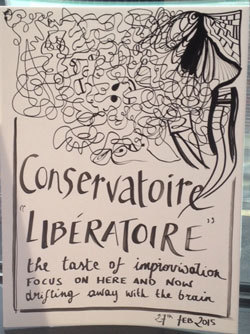

This year’s Reflective Conservatoire Conference brought together more than 400 participants from schools from all over Europe as well as the States, Canada, Brazil, Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Singapore and Estonia among others. It drew lots of students too, who were attracted by free admission to the sessions and an amazing graphic artist group called Creativeconnection which captured in images the debate and discussion as it happened in real time. The artists have allowed me to use some of their graphics to illustrate this blog.

This year’s Reflective Conservatoire Conference brought together more than 400 participants from schools from all over Europe as well as the States, Canada, Brazil, Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Singapore and Estonia among others. It drew lots of students too, who were attracted by free admission to the sessions and an amazing graphic artist group called Creativeconnection which captured in images the debate and discussion as it happened in real time. The artists have allowed me to use some of their graphics to illustrate this blog.

Session topics covered the whole gamut of current musical debate including: Conservatoires in Society; Critical Artistry; the Orchestral Musician of the Future; Peer Learning; the Conservatoire in 2020; Improvisation; and of course Entrepreneurship. I was part of one workshop session led by a great teacher and theatre director Ken Rea who guided acting students and musicians through a number of experimental performance techniques. I have to say that I have rarely seen musicians — after recovering from their initial shock and horror at what was being proposed — respond so creatively to the opportunity of returning to their childlike selves. It seemed as if the walls of performance anxiety fell into a mass of broken pieces by the session’s end. I hope so much that this is the start of a great journey for them because what I witnessed could completely change the way they communicate as artists.

I heard a young conductor David Ramael outline his new thinking about concert presentation and how he wants to select musicians for his new orchestra in Antwerp based on new skills of communication and improvisation. And Bindert Posthuma, Deputy Director of the Prince Claus Conservatoire in Groningen, The Netherlands, stated flatly and unequivocally that everything needs to change, that the students are way ahead of their institutions, as are the faculty who have learnt new skills outside of their formal training. This was all heady stuff and exploding with potential and energy and questions.

I heard a young conductor David Ramael outline his new thinking about concert presentation and how he wants to select musicians for his new orchestra in Antwerp based on new skills of communication and improvisation. And Bindert Posthuma, Deputy Director of the Prince Claus Conservatoire in Groningen, The Netherlands, stated flatly and unequivocally that everything needs to change, that the students are way ahead of their institutions, as are the faculty who have learnt new skills outside of their formal training. This was all heady stuff and exploding with potential and energy and questions.

So what of David Myers? He and his group had the most interesting discussion title of the entire conference: “A Manifesto for Radical Change in the Education of the C21 Musician.” The presentation summarized the report Myers’ task force prepared for the College Music Society, which represents over 7,500 musicians and scholars from the States and beyond. The amusing Franklin paraphrase was a reflection of what the authors described as the “inertia of the prevailing paradigm.”  Their major premise is that change is inevitable and that failure to change can be fatal. In looking at contemporary society, they discussed the role of a musician, why creativity is important, and how the curriculum needs to reflect these changes. Traditions, as they see it, are in decline as shown by the dwindling jobs in music, audiences, universities, orchestras and music programmes, which now seem to be limited to the economically privileged. They see students already living the change but the training institutions lag behind in their development and thinking. They seemed to be reiterating Simon Rattle’s oft heard crie de coeur that being a musician is now more about improvisation, composing, teaching and performing than just straight performance.

Their major premise is that change is inevitable and that failure to change can be fatal. In looking at contemporary society, they discussed the role of a musician, why creativity is important, and how the curriculum needs to reflect these changes. Traditions, as they see it, are in decline as shown by the dwindling jobs in music, audiences, universities, orchestras and music programmes, which now seem to be limited to the economically privileged. They see students already living the change but the training institutions lag behind in their development and thinking. They seemed to be reiterating Simon Rattle’s oft heard crie de coeur that being a musician is now more about improvisation, composing, teaching and performing than just straight performance.

It was a startling presentation and I look forward to reading their report, but I also wanted to check on some of these major assumptions with attendees and I found a great resource in the Conference’s own web site which contains blogs from the participants which supported much of what they had to say. Here is one from Doctor Heidi Partti a researcher, educator, musician at the Sibelius Academy Helsinki:

“The importance of supporting student’s growth into ownership of their learning process and agency as artists and professionals should be infused throughout the curriculum and practices in our higher education system. Encouraged to design and follow their own learning and career paths. How much demand do we put on students reflect our own ambitions? How much do we allow them genuine freedom to explore, take risks, and even fail in our institutions? Do we dare to urge students to stop, look, and listen, and to do this frequently and to commit frequently themselves to reflecting on their choices? How are we deliberately advancing a culture of activism within which students are empowered to see themselves as change agent and to raise their voices as artists and pedagogues for a more socially just and inclusive world?”

All these questions are the right questions and there are probably countless more we should add. Did the Conference at the Guildhall change the world? Not this time, it didn’t. But given the time and freedom to research, analyze, think, discuss, and reflect that we all need in our ever more busy lives, we could start to do things very differently. This could allow us to place music at the centre of human endeavor and innovation rather than languishing at the periphery as many see us at the moment.

Thank you, Guildhall, for providing us this expansive moment to discuss the now and the future… And let’s forget that Ben Franklin reworking.

No comments yet.

Add your comment