The Struggle of Harmony and Invention

Timed for Halloween, with its period instrument musicians sporting masks and witches hats, and a program featuring Tartini’s Devil’s Trill, the Handel and Haydn Society (known affectionately as H+H) kicked off its Bicentennial season with great festivity last week. The undisputed star of the evening was the amazing violinist Aisslin Nosky, who directed the almost all Vivaldi programme from the first stand — that prop appropriately adorned with devil’s horns. For me, the performance made a powerful statement about all that is exciting, unique and important about the Early Music, or, perhaps more accurately, the historically informed performance movement. And it raised, once again, the question of what has happened to this movement in the U.S. and abroad. But more about that later.

Over its 200 years, H+H has been an essential component of Boston’s concert life, morphing with changing styles and tastes. In recent decades, it has had many distinguished music directors from the Early Music stable. Currently Harry Christophers is the very dynamic leader and in the past they have had Roger Norrington (Artistic Advisor for two years), Christopher Hogwood, and Grant Llewellyn. But it was Thomas Dunn who shook things up and introduced the idea of historically informed performance practice when he famously presented the annual Messiah performances in 1967 with reduced orchestra and chorus. Thereafter, he presented each year a different version of Messiah based on all the various incarnations it had during Handel’s lifetime. Dunn, however, drew the line at using period instruments in Boston’s Symphony Hall because he believed that acoustic space was too large and, at least initially, that the musicians had not fully mastered the instrumental demands. His successor Christopher Hogwood, however, took the plunge, utilizing a period instrument orchestra that benefitted from the increasingly virtuosic cadre of early music players in the area. And so it has remained ever since.

Over its 200 years, H+H has been an essential component of Boston’s concert life, morphing with changing styles and tastes. In recent decades, it has had many distinguished music directors from the Early Music stable. Currently Harry Christophers is the very dynamic leader and in the past they have had Roger Norrington (Artistic Advisor for two years), Christopher Hogwood, and Grant Llewellyn. But it was Thomas Dunn who shook things up and introduced the idea of historically informed performance practice when he famously presented the annual Messiah performances in 1967 with reduced orchestra and chorus. Thereafter, he presented each year a different version of Messiah based on all the various incarnations it had during Handel’s lifetime. Dunn, however, drew the line at using period instruments in Boston’s Symphony Hall because he believed that acoustic space was too large and, at least initially, that the musicians had not fully mastered the instrumental demands. His successor Christopher Hogwood, however, took the plunge, utilizing a period instrument orchestra that benefitted from the increasingly virtuosic cadre of early music players in the area. And so it has remained ever since.

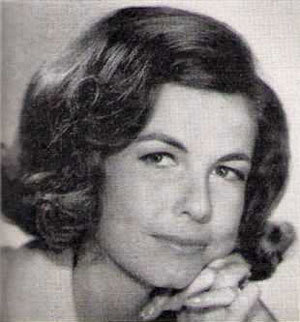

For 40 years, then, H+H has played an important role in the Early Music movement in Boston and shares its excellent position with Boston Baroque, the Boston Early Music Festival, Emmanuel Music (founded by NEC alumnus Craig Smith), the Boston Camerata, Cantata Singers, Sarasa Chamber Ensemble and many others. For those interested in exploring the concert options, try this website. Boston also became an important center for period instrument making, with, for example, two of the most famous modern harpsichord builders, Frank Hubbard and William Dowd, opening workshops here. (William Dowd in photo with a 1987 instrument from his workshop.)

For 40 years, then, H+H has played an important role in the Early Music movement in Boston and shares its excellent position with Boston Baroque, the Boston Early Music Festival, Emmanuel Music (founded by NEC alumnus Craig Smith), the Boston Camerata, Cantata Singers, Sarasa Chamber Ensemble and many others. For those interested in exploring the concert options, try this website. Boston also became an important center for period instrument making, with, for example, two of the most famous modern harpsichord builders, Frank Hubbard and William Dowd, opening workshops here. (William Dowd in photo with a 1987 instrument from his workshop.)

What is curious about this, however, is that Boston seems to be a small island of historically informed performance in a sea of more conventional music making in the U.S. The great Early Music movement that swept across Europe 30 years ago bypassed or only superficially touched much of the country, and today there are only the rich but isolated pockets of Early Music in Boston, parts of the West Coast, and NYC. There are no great new orchestras in the States challenging conventional practice such as the l’Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique (founded 1989), the Monteverdi Choir & Orchestra (1964), the English Concert (1970), the Parley of Instruments (1979), the Academy of Ancient Music (1973), Les Arts Florissants (1979), La Chapelle Royale (1977), La Petite Bande (1972), l’Orchestre des Champs-Élysées (1991) or the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment (1986). The States have not produced nearly as many great performers, conductors, and exponents in this field as Europe has what with Trevor Pinnock, Frans Brueggen, Ton Koopman, John Eliot Gardiner, Jordi Savall, Philippe Herreweghe, William Christie, Rachel Podger, Sigiswald Kuijken, Giuliano Carmignola. And this list can go on. Many musicians in this country express an interest in new styles of performance practice but this doesn’t seem to have resulted in the critical mass needed for new developments, and audiences seem little interested. There are a sprinkling of programmes in the major music schools, mostly on the graduate level, with Juilliard and Indiana having the most extensive.

In Europe the public demand for historic performance practice has proved to be one of the greatest growth areas for classical music. Today the major symphony orchestras would never dream of playing anything Baroque and are very reserved about Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. And if they do include classical repertoire in their concerts there is a very deep bow to historic performance practice with different articulation and deployment of vibrato and bow. Glyndebourne Opera, that bastion of the English elite, despite having a contract with the London Philharmonic Orchestra which goes back many years, will bring in the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment for any of its Mozart productions. The great Russian violinist Maxim Vengerov plays his solo Bach sonatas on a Baroque violin and the Berlin Philharmonic expects all its players to have wide experience in early music practice. The major conservatories have departments dedicated to historic performance practice and the quality of musicians graduating and going out into the field is generating yet more creativity and developments.

Now 80 years old, Roger Norrington continues to push the boundaries, having brought composers such as Berlioz and Schumann into the mix and even performing Mahler symphonies without string vibrato. (He maintains that the now conventional rich application of vibrato only became common practice in the 1920s!). You should hear the astonishing discoveries he makes in this so familiar repertoire by returning to the styles current at the time of composition. It all makes for a really exciting creative time of experimentation and discovery which is good for our art form.

Of course, some musicians have reacted to historic performance practice as a threat and have dismissed the whole thing as some kind of musical aberration whose perceived low performance standards are just not acceptable. One only has to listen to Aisslinn Nosky, however, to understand that performance standards in the Early Music movement can be transcendent. And, of course, there are routiniers who play in all styles.

My own epiphany with the early music world came when I was running the City of London Sinfonia [CLS] with the English conductor Richard Hickox in the early 1980s. The CLS was a modern orchestra employed on a per service basis and they were and are stellar performers. We were engaged to play for a production of Handel’s opera Alcina with Arleen Auger in the title role — a performance which I shall never forget — and then for a recording for EMI. EMI dictated that the orchestra must be a Baroque band and we were left with the very difficult task of informing our loyal players that they had lost the gig and then engaging freelance Baroque players for the new orchestra which suddenly had “Baroque” added to its title. It somehow all came together and I attended the first rehearsal with frankly very mixed feelings. We had not looked after our first orchestra and I was not really enamoured of Baroque practice anyway. Well, all that was about to change. The sound the orchestra made, particularly the strings and especially in those slow lamentoso arias that Auger sang so exquisitely, was breathtakingly beautiful and I was smitten. Today I just cannot hear certain repertoire unless it’s given this type of style and treatment.

My own epiphany with the early music world came when I was running the City of London Sinfonia [CLS] with the English conductor Richard Hickox in the early 1980s. The CLS was a modern orchestra employed on a per service basis and they were and are stellar performers. We were engaged to play for a production of Handel’s opera Alcina with Arleen Auger in the title role — a performance which I shall never forget — and then for a recording for EMI. EMI dictated that the orchestra must be a Baroque band and we were left with the very difficult task of informing our loyal players that they had lost the gig and then engaging freelance Baroque players for the new orchestra which suddenly had “Baroque” added to its title. It somehow all came together and I attended the first rehearsal with frankly very mixed feelings. We had not looked after our first orchestra and I was not really enamoured of Baroque practice anyway. Well, all that was about to change. The sound the orchestra made, particularly the strings and especially in those slow lamentoso arias that Auger sang so exquisitely, was breathtakingly beautiful and I was smitten. Today I just cannot hear certain repertoire unless it’s given this type of style and treatment.

It strikes me as a great shame that the U.S. has not experienced quite the same conversion as Europe (with the exceptions I have noted above). The Early Music movement can tell us so much not just about history but about bringing history to modern day life in the most compelling and potent ways. The Canadian early music scene appears to be far more developed and Aisslinn Nosky works as a frequent member and director of I Furiosi Baroque Ensemble based in Toronto. But in the states we lag behind in supporting this brilliant style of performance and performance practice. We should be grateful, though, that we have organizations such as H+H and the powerful direction of Aisslinn and Harry Christophers. Music making such as we heard on Halloween can only result in an increased appetite for such experiences and perhaps to further development of the movement. Let’s hope so.

No comments yet.

Add your comment