The Baton and the Jackboot – Then and Now

Have you ever played that game about which famous characters you would love to be seated next to at a dinner party? For some, it might be Homer or Shakespeare or Abe Lincoln. My choice has varied over the years. Sometimes it’s historical — Brutus, for instance; other times, it’s cultural — like Christopher Marlow or a young Tolstoy. The quality of conversation would be amazing and then there are all those questions to be asked.

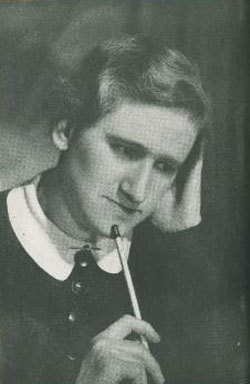

But I have just read a book, whose author is now at the top of my dinner party list. Her name is Berta Geissmar and she was born in Mannheim, Germany in 1892 and died in London in 1949. She was a doctor of philosophy, a musician, and an author who wrote one of the most compelling memoirs I have ever come across. In fact, it’s much more than a memoir or autobiography — more a work of history, starting in Mannheim after the First World War and ending in war-torn London in 1943.

But I have just read a book, whose author is now at the top of my dinner party list. Her name is Berta Geissmar and she was born in Mannheim, Germany in 1892 and died in London in 1949. She was a doctor of philosophy, a musician, and an author who wrote one of the most compelling memoirs I have ever come across. In fact, it’s much more than a memoir or autobiography — more a work of history, starting in Mannheim after the First World War and ending in war-torn London in 1943.

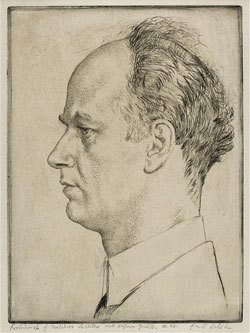

Dr. Geissmar (I just have to call her that) became, during a long career in music, the Private Secretary to the great German conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler and, later, to the quixotic English conductor Sir Thomas Beecham. Her book, The Baton and the Jackboot touches upon all the historical events of the day, but from the inside.

So, we read about life in Germany in the 1920s, and then the terrible rise of Nazism, her own persecution in the 1930s (she was a Jew who had been brought up a Protestant) and her eventual escape from Germany. She touches on all the great artists, composers, and cultural figures of the time — Richard Strauss, Bronislaw Huberman, Mengelberg, Alma Mahler, the Wagner family, Hindemith, Kreisler and Casals, all of whom she knew well.

The poignant image she creates of Germany before National Socialism is one where culture and, in particular music, was absolutely at the forefront of life. Her father, for instance, was a lawyer, but took his violin to the office to practice between meetings. And what a violin — the “Vieuxtemps” Strad. Her home and the community of Mannheim revolved around music, what with all the amateur musicians devoted to chamber music, who she reports as being of extraordinarily high standards, and drop-in visits from musicians like Joseph Joachim who came to pay his respects.

But the central story in the book is her relationship with Furtwängler, with whom she worked for 14 years, and his meteoric career from posts with regional German orchestras to the music directorship of the Berlin Philharmonic. His celebrity and star power, however, were to become his greatest liability once the Nazis were in power when he was forced to confront his nemesis Hitler and face the choice of remaining in place or emigrating. All of which we will come to in a moment.

But the central story in the book is her relationship with Furtwängler, with whom she worked for 14 years, and his meteoric career from posts with regional German orchestras to the music directorship of the Berlin Philharmonic. His celebrity and star power, however, were to become his greatest liability once the Nazis were in power when he was forced to confront his nemesis Hitler and face the choice of remaining in place or emigrating. All of which we will come to in a moment.

Dr. Geissmar’s relationship with the great conductor was very close (what Mrs. Furtwängler thought of all this we will never know), but there is a deep undertone of admiration and love for the man. There are some beautiful vignettes of the relationship too. For instance, Furtwängler takes her on a walk and introduces her to the childlike joys of eating cherries and then seeing how far one can spit the pits. (Actually I could see Simon Rattle doing that as well.)

Furtwängler’s career is astonishing. Consider the engagements: The Berlin Philharmonic, Vienna Philharmonic, Vienna State Opera, Bayreuth, the New York Philharmonic, Covent Garden. He, together with Toscanini and Bruno Walter, were the most galvanizing conductors of the first part of the 20th century. Listening to his many recordings, which are still readily available, is truly a great experience, thrilling the listener with their passion and searing commitment.

Dr. Geissmar is there throughout, organizing, making certain that the Maestro’s life runs like a well-oiled machine. The impression I have is of someone who worked with only one purpose, to serve the Maestro, and if this meant getting up at 4 a.m. to rush to the train station to reserve his favorite compartment, then that is what it took. Her organizational expertise spilled over to running the Philharmonic and its tours, which she seemed to do with consummate capability.

Then came the rise of the Nazis, and there is much that we can learn from Geissmar’s story, with direct application to events today. The Nazis would eventually control every single aspect of life in Germany — it’s called totalitarianism for a reason. But to begin with, they were chaotic and didn’t have a plan, so they pushed the boundaries to see what would happen. It was a time of incrementalism, a gigantic salami slicer of change, which went unchecked both nationally and internationally. Hitler got away with it… the disenfranchisement and subsequent annihilation of the Jews, the invasion of Czechoslovakia, the Austrian Anschluss, and no country put a stop to it until 1945 and the end of the war.

Then came the rise of the Nazis, and there is much that we can learn from Geissmar’s story, with direct application to events today. The Nazis would eventually control every single aspect of life in Germany — it’s called totalitarianism for a reason. But to begin with, they were chaotic and didn’t have a plan, so they pushed the boundaries to see what would happen. It was a time of incrementalism, a gigantic salami slicer of change, which went unchecked both nationally and internationally. Hitler got away with it… the disenfranchisement and subsequent annihilation of the Jews, the invasion of Czechoslovakia, the Austrian Anschluss, and no country put a stop to it until 1945 and the end of the war.

Hitler was known to love music, Wagner in particular, and he attended concerts and opera on a regular basis. (One of his generals remarked, not in this book, that Hitler didn’t understand music at all but liked the noise it made.) Furtwängler was Germany’s most famous musician and the Nazis wanted to exploit this as much as they could. They infiltrated the Berlin Philharmonic, eventually imposing their racial ban against Jews in the orchestra. Furtwängler opposed them in repeated meetings with Goering (who had the orchestra in his portfolio) and Hitler, often ending in long shouting matches. At the end of which, concessions would be made by the Nazis only to be reneged upon almost immediately.

“A crazy phobia on the part of the Nazis had drawn our unique organization into the power of unqualified and inept busybodies. Furtwängler’s great art, naturally, could not be touched, but the strain on his nerves due to all these complications was increased and this became more and more noticeable. With great distress, I saw how completely he had fallen a victim to the war on words. However, I concealed my feelings and did what I could.” — Berta Geissmar

Dr. Geissmar was under intense scrutiny at this time as well and was known as “that troublesome Jewish secretary.” The story of her passport being confiscated is a harrowing tale because without it, of course, she was trapped in Germany and at the Nazis’ mercy.

“… [H]e spared no effort to uphold the standards of pure art, inspired by the conviction that it was his mission to fight for what he judged to be right as long as it was in his power to do so.”

But her account does raise the perennial question of the artist’s responsibility when there is overwhelming evidence of oppression and evil. Does the artist — can the artist — stand above it all because his central concern is the primacy of art, and real world events are less important? Clearly this question was very much on Dr. Geissmar’s mind. And while she takes a defensive posture toward Furtwängler, she also quotes verbatim open letters written by the great Polish violinist Bronislaw Huberman that offer a different perspective. The violinist, who created the Palestine Orchestra that eventually became the Israel Philharmonic, declined Furtwängler’s invitation to play a concerto with the Berlin orchestra in 1933 because he, along with numerous other prominent musicians, was boycotting Germany on the strength of its racial ban on Jews. He published his reply to Furtwängler, following up in 1936 with a rebuke of “German intellectuals.” Here are several excerpts:

“…There is, however, also a human-ethical side to the problem. I should like a definite rendering of music as a sort of artistic projection of the best and most valuable in man.

Can you expect this process of sublimation, which presupposes complete abandonment of one’s self to one’s art, of the musician who feels his human dignity trodden upon and who is officially degraded to the rank of a pariah? Can you expect it of the musician to whom the guardians of German culture deny, because of his race, the ability to understand ‘pure German music’?”–Bronislaw Huberman in 1933

“…Two and a half years have passed. Countless people have been thrown into gaols and concentration camps, exiled, killed, and driven to suicide. Catholic and Protestant ministers, Jews, Democrats, Socialists, Communists, army generals became the victims of a like fate…Well, then, what have you, the “real Germans,” done to rid conscience and Germany and humanity of this ignominy… Where are the German Zolas, Clemenceaus, Painlevés, Picquarts, in this monster Dreyfus case against an entire defenseless minority?

“Before the whole world, I accuse you, German intellectuals, you non-Nazis, as those truly guilty of all these Nazi crimes, all this lamentable breakdown of a great people–a destruction which shames the whole white race…”–Bronislaw Huberman in 1936

Huberman’s open letters are separated in time by nearly 80 years from a similar letter from another great violinist, Gidon Kremer, who recently wrote about the situation we are all watching in Russian and Ukraine. The similarities are deep and disturbing:

“I fail to understand some of my colleagues, who (for their own convenience?) support the state of affairs and its political intimidation. They (no names here!) call it “patriotism”. Individually, they have the right to make their own choices. But as artists, shouldn’t their duty be to stand up for truth, while sharing positive energies?

For me, true loyalty to one’s country or to one’s audience is to serve spiritual values and not to become convenient ‘puppets’ for those politicians who are making loud but fundamentally flawed statements and expressing apparently powerful doctrines, but who actually seem indifferent to human suffering and tragedies. At the same time, cherishing the cultural traditions of the Russian past as I do, I am eager to remind our audiences of different values associated with ‘Russia.’

We should not ignore the fact that wherever terror and killings are the language of so-called “politics”, human values are at stake. By contrast, music and arts have the possibility to spread kindness and understanding. And in the light of the present situation, I feel that it is becoming increasingly imperative to focus on values of that kind.

I know that our small event is not going to change the world order and at best will have just a tiny influence on the struggle between fighting and negotiating parties. Yet at the same time I feel compelled to express my concerns and my anxiety for those in need, irrespective of whether they are in Ukraine or in Russia.

Killers and liars must be exposed and condemned. There is not a slightest chance of ever achieving a better world if we simply distance ourselves from terror. Willingly or unwillingly, all of us “participate” in the process by ignoring those who suffer. Each of us has a responsibility. And each of us has a choice – to remain indifferent and silent or find a way to speak out.”–Gidon Kremer, September 2014

So, as we look again at the example of Furtwängler, one has to ask: Who can look into the heart of another human being and understand their true motives and how can we judge? Hero or coward? What would we ourselves have done? Furtwängler, despite many offers from the U.S. decided to stay in Germany. The Berlin Philharmonic eventually became the Reich’s orchestra and its conductor remained throughout the war, eventually escaping to Switzerland pursued by the SS, with Himmler swearing to put him in a concentration camp.

There are many stories of Furtwängler helping Jewish colleagues to escape, but all this evidence was overridden by nearly universal opprobrium after the War when the conductor was denounced as a collaborator and forced to undergo “deNazification.” Only the passionate and courageous advocacy of the young violinist Yehudi Menuhin, himself a Jew, made possible Furtwängler’s partial rehabilitation.

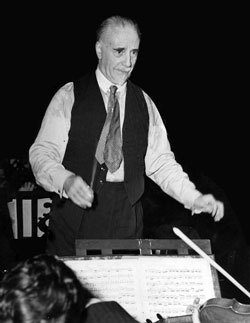

Returning to Dr. Geissmar’s personal story, she was forced to leave Germany, went to London, and started a new career as Secretary to Sir Thomas Beecham who was then running the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden as well as the London Philharmonic Orchestra. She loved London, had a flat there (which she shared with 84 rats until they were dispatched by an amazing Pied Piper), and became a part of the London musical scene. She served Sir Thomas with the same precision, insight, and charm as Furtwängler. (It is interesting to note that the conductors knew one another well and displayed mutual respect and admiration. Sir Thomas even underwrote the first UK tour of the Berlin Philharmonic because of financial difficulties.)

Returning to Dr. Geissmar’s personal story, she was forced to leave Germany, went to London, and started a new career as Secretary to Sir Thomas Beecham who was then running the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden as well as the London Philharmonic Orchestra. She loved London, had a flat there (which she shared with 84 rats until they were dispatched by an amazing Pied Piper), and became a part of the London musical scene. She served Sir Thomas with the same precision, insight, and charm as Furtwängler. (It is interesting to note that the conductors knew one another well and displayed mutual respect and admiration. Sir Thomas even underwrote the first UK tour of the Berlin Philharmonic because of financial difficulties.)

Dr. Geissmar remained in London during the blitz, which destroyed her flat and her library. She became part of that band of musical heroes who promoted music as the spiritual balm needed during a period of world destruction.

“…It has been recorded in a thousand ways, and yet no one who has not witnessed it can have an idea of the greatness shown by the people of London: the calm resolution of all the Defense Services, the patience and kindliness of those gathered in the shelters (often insufficient in the beginning), the stubbornness in carrying on after sleepless nights and harassed days, the indomitable courage of everyone, and last but not least the ever present humor, the sympathy without sentimentality–the greatness of it all.”

Her stories of musicians and audiences staying through concerts despite the bombs falling and the London Symphony Orchestra musicians manning a food canteen for rescue squads and firemen bring a tear to this eye. Indeed, a lasting impression of this book is the intense symbiosis between the general populace and the orchestra, each rising to the occasion to meet the other’s needs. (What an exemplary lesson for us today!) So, for example, after the bombing of Queen’s Hall, which destroyed not only the building but also the musicians’ instruments, the people came forward with replacements:

Her stories of musicians and audiences staying through concerts despite the bombs falling and the London Symphony Orchestra musicians manning a food canteen for rescue squads and firemen bring a tear to this eye. Indeed, a lasting impression of this book is the intense symbiosis between the general populace and the orchestra, each rising to the occasion to meet the other’s needs. (What an exemplary lesson for us today!) So, for example, after the bombing of Queen’s Hall, which destroyed not only the building but also the musicians’ instruments, the people came forward with replacements:

Having arranged to play in the Albert Hall, “…the most urgent need of the moment was the question of the instruments. The B.B.C. had kindly informed the public of the Orchestra’s difficulties. From the moment of that appeal there was no peace. There was a continuous procession from every quarter. People queued up to the Orchestra’s office laden with violins and violas. Cellos were deposited outside the doors. The Orchestra had meanwhile left with borrowed instruments for provincial concerts fixed up long before, and wherever they appeared, people turned up with instruments! During their absence the three office telephones rang incessantly with people offering instruments, and a special person had to be engaged to deal with these calls alone. By every post hundreds of letters arrived about instruments only, and an emergency staff of voluntary helpers spent days and days opening the letters.”

We leave Dr. Geissmar in 1943 writing this book, sitting in the sunshine at Adrian Beecham’s farm in Warwickshire. It is curious to think that Hitler and Goebbels and that team of brutal gangsters were still alive when she wrote her story and that the war was far from over.

I will leave her with this last word:

“How ironical it is that a movement–describing itself as ‘National Socialism’–should give the German people an empty façade of dictatorial splendor and should destroy in them the warmth of humanity and the dignity of simplicity–all that is natural and free.”

No comments yet.

Add your comment