Deep Song

Amy Winehouse’s death just a few months ago was a great tragedy and has deprived us of a unique voice and creative spirit. Her career was brief, meteoric, self-destructive and full of moments of amazing achievement.

The response that she was able to command from her fans was at once affirming and provocative and in many ways enabled her worst excesses. Her followers seemed to will her down a path towards an inexorable conclusion. But in a way she was living out the covenant that any extraordinary artist has with their public. The public demands more and more of its heroes; it has expectations of performance that are excessive and rapturous, but with only one way for the artist to meet that need–with a self-sacrificial outpouring of gifts and soul.

We love the romantic notion of artists who have given everything, whose talent is extinguished too early, whose covenant with us is ruptured by an untimely ending. Just think of our relationships with Mozart, Schubert, Lorraine Hunt Lieberson, Jimi Hendrix, Jacqueline du Pré, Kurt Cobain, Maria Callas: we are suffused by an inner yearning still for more but with an acknowledgement of what was given and sacrificed. Some of the artists I have selected for this article certainly fall within this category, but others do not and are alive and well, playing wonderfully, and enjoying happy family lives. But they all share a characteristic for deep song, the ability to sing or play through the ground from the soles of their feet, and into their voices and fingers and, by doing so, to change the world.

My first is a young violinist whose career never really happened. Only glimpses of performance have been captured, and we are left with just a handful of recordings. These were made by the legendary impresario Walter Legge, who discovered in 1940 a boy of sixteen studying with the great teacher Carl Flesch and took him into the recording studio to perform a few salon pieces.

His name was Josef Hassid (1923-1950), and there were many extravagant claims made about his playing and artistry. Fritz Kreisler heard him and was quoted as saying, “A Heifetz violinist comes around every 100 years, a Hassid every 1000.” When you listen to his rendition of Sarasate’s Playera, you can recognize what he means. It is as though he has stood on a New York bridge with Sonny Rollins [i] focusing upon producing just one note, and he allows its sound to transmute into every dark colour imaginable.

The work is not a virtuoso showpiece; instead, it is a song expressing profound emotions of pain and knowing.

As a result of his very candid autobiography Straight Life, Art Pepper (1925-1982) provoked all sorts of “voyeurism” when he came to London to perform at Ronnie Scott’s Club in 1980 with Milcho Leviev. In his past life he had turned to drugs, to criminal behavior, had served time in St. Quentin, but had emerged from this cauldron of desperation and experience with so much to tell us. And in the album “Blues for the Fisherman,” written by him and Leviev , he lays out his soul. His Make a List, Make a Wish is for me the supreme example of his artistry as a performer and composer. Bassist Tony Dumas has a really strong riff that is repeated and repeated, and every repetition is different—subtly and transformationally. Above it there are two long solos, first from Pepper and then, after a climax that has burnt and smoldered, Leviev takes us structurally to almost the same place but in a different way.

Jacqueline du Pré (1945-1987)

Jacqueline du Pré (1945-1987) enjoyed a meteoric solo career of little more than ten years during which time she consumed music and communicated her love and passion. In 1973, I heard her play the Elgar Concerto in London, a work forever associated with her. This was during the period of her very brief return to the concert platform after a two year break before her illness overcame her. Sir Neville Cardus, who wrote with equal passion about cricket and music, and who was knighted by the Queen for his services to both, wrote this astonishing description of her Elgar, “She went to the heart of the matter with a devotion remarkable in so young an artist so that we did not appear so much to be hearing as overhearing music which has the sunset touch on it, telling the end of an epoch in our island story and also telling of the composer’s acceptance of the end. The bright day is done, and he is for the dark. And she got the wounding juice out of this self-revealing work.” The Saint-Saens First Concerto from 1971 which I have selected is not musically on the same page as the Elgar but in terms of performance and sound, Du Pré will stop you in your tracks.

Lionel Hampton

Now this one is a total must. Lionel Hampton (1908-2002) with his All Stars playing “Stardust” from the Civic Auditorium, Pasadena, in 1947. Something was happening that night. The band took the standard and never looked back. Each solo builds on the next and is in itself unique. Willie Smith on alto sax is downright dirty. Corky Corcoran’s tenor is floating, sensuous, seductive. Charlie Shavers’ trumpet is virtuosically humorous. Slam Stewart, bass, does that astonishing improvisational trick of playing and singing what he is playing at the same time, at the distance of an octave. I adore this sound. Every one of them is sensational. The best ever. Then . . . in comes Lionel Hampton on vibes with an extended break which leaves everyone else at home. This is music making shaking with energy and discovery. And Hampton knows it. He knows how good it is and that this is a new place. It becomes more and more fluent, finding inspiration in every phrase of the standard. I played this once to my good friend and colleague the conductor Andrew Litton in his car just before an important dinner. He couldn’t leave and just sat there, transfixed.

Sarah Vaughn (1924-1990)

Sarah Vaughan (1924-1990) recorded a live album in 1957 at Mister Kelly’s in New York City with her trio—Jimmy Jones, Richard Davis, and Roy Hayner. It contains a track called “Be anything but darling be mine,” in which she demonstrated not just her voice and total command but her ability to sing as though she was an instrument rather than a voice—particularly the saxophone. Her muted, covered voice in certain passages takes us to new colours and feelings.

Eddie South (1904-1962)

Eddie South (1904-1962) was an African-American jazz violinist, classically trained, who, because of the savage racism of the time, could not pursue a career in a symphony orchestra. Instead, he developed into perhaps the greatest jazz violinist of all time and, in the 1930’s, became the mentor of Stéphane Grappelli when he visited Paris. His sound and imagination are extraordinary. Listen to his “Eddie’s Blues” (with Django Reinhardt accompanying him with a variety of rhythms and harmonic punctuations) for a great example of his originality as a performer and composer. What he produces in this recording dating from 1937 (and just think of the great violinists dominating the string world at that time) is a new sound and method of playing the violin. It is fluently virtuosic but only to expressive purposes. The sound is overall very sweet, but he can turn a note as well as a slide with a variety of different vibratos and colours. And then there is the percussive use of the bow adding punctuation to his phrasing. The first time I heard this track I could not believe what he was achieving, and each time I listen to it, I find new points of originality which amaze.

South’s accompanist, Django Reinhardt (1910-1953), is most associated with the Quintet of the Hot Club of France and Stéphane Grappelli. Reinhardt, Grappelli, and South collaborated many times, including some experimental crossovers with a jazz version of the Bach Double and this was many years before Jacques Loussier or Ward Swingle. Reinhardt was a gypsy born in Belgium to the Manouche gypsy family. At the age of eighteen, he was severely burnt in a caravan fire and suffered major damage to the third and fourth fingers of his left hand. His doctors stated that he would never play again. They were wrong. How he plays with basically two operational fingers defies belief. This is acoustic guitar playing in a totally different world from anything before or after. Only Jimi Hendrix in the 1960s created something as original. Reinhardt makes a unique sound. It had unspeakable character and colour and a sensuous quality which strokes the air. His virtuosity is given sometimes to amaze, always within character, but held in reserve as something that he has facile dominance over. He recorded a few purely solo works of his own composition. “Parfum” is full of simplicity and gentle, exotic chord sequences. The melodic line is sung with an accompaniment as delicate and soft as though from another instrument.

Last summer my wife and I traveled to Lisbon, Portugal, for a first visit. One of the main attractions for us was to experience the musical form, Fado, a sort of mixture of the blues and Flamenco. We went to many Fado clubs and heard some amazing singers. The format was always the same. Four different singers, performing for not longer than fifteen to twenty minutes each. No amplification. A small instrumental group of two guitars and a mandolin playing melodic lines and melismas and the voice hauntingly telling its story in thunderous declamatory form.

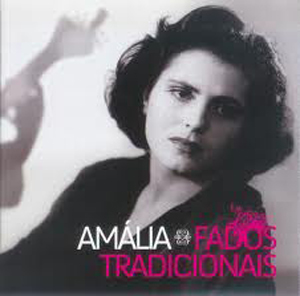

Amalia Rodriques (1920-1999)

All the performances we saw were given in cellars using the natural excellent acoustic provided by arches, the sound filling a room usually seating 100-200 people. It is a sound of the greatest complexity speaking to our humanity. The Queen of Fado was Amalia Rodrigues (1920-1999), whose recorded legacy shows how it can be done.

I first came across British Baroque violinist Rachel Podger about eight years ago when someone played for me her recording of the Bach Solo Sonatas and Partitas. It was a revelation in terms of blowing new life, energy, and insight into these masterworks. Consider this excerpt, the Gavotte and Rondo from the E-Major Partita. Podger works as a soloist, but in reality she is a confirmed collaborator. Her Bach Violin Concerti, in particular the last movement of the A minor, is a case in point. Instead of the old-fashioned virtuoso playing with a large orchestra accompanying rather like a herd of wildebeest with the contrapuntal lines so lost and muddy, we hear everything with the solo line merely part of the musical counterpoint and argument rather than the only line. It is like a chilled glass of San Pellegrino with lime, full of familiar and unfamiliar tastes. It is Bach reinvented. If you can get hold of it, I highly recommend it. (We at NEC were delighted to host Podger in a public masterclass in September 2010 where she worked with several of our string players in works of Bach.)

Jascha Heifetz (1901-1987)

So I will end with the last public performance given by Jascha Heifetz (1901-1987), the doyen of violinists and one of the greatest virtuosos of the 20th century. In his last recital at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in 1972, he amazed as always with his showpieces, but with his final works he toned the brilliance down and instead elected to play short melodic pieces, often with mute. The Manuel de Falla “Nana” is for me the best example of simple melodic playing coloured by the articulation and ornamentation of Flamenco. It is as though he had walked away from the power Ferrari of his virtuosity and sat quietly in the melting sun allowing his soul to sing.

[ii]

[i] Rollins famously reinvented his playing by practicing his sax on the Williamsburg Bridge in NYC during a two-year musical sabbatical beginning in 1959. Returning to performing, he named his comeback album The Bridge.

![]()

No comments yet.

Add your comment