by Garrett Wellenstein

The Eastman School Symphony Orchestra (ESSO) will present its second concert of the semester tomorrow, Saturday, February 20, 2016, in Kodak Hall. Maestro Neil Varon opens the concert with a bang, conducting Alexander Borodin’s Overture to Prince Igor, followed by the lush, mystical harmonies of Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis for double string orchestra, conducted by second-year MM student Garrett Wellenstein. Sergei Prokofiev’s bold and colorful Suite from Lieutenant Kijé, conducted by first-year MM student Samuel Pang, will end the program. The vibrancy and intense colors of the Borodin and Prokofiev serve as a perfect foil to the darker, moodier Vaughan Williams, and the orchestra has been hard at work over the past two weeks to render the scores to their fullest potential.

This concert also showcases Eastman’s master’s conducting students, who are guided every step of the way in their preparation of the orchestra by Professor Varon. Eastman’s graduate conducting program is unique among those around the country in terms of the amount of time student conductors receive in front of the orchestra, working with the students in a hands-on capacity to prepare works over the course of several weeks of rehearsal. The works they conduct are chosen in careful consultation with Professor Varon, who seeks to highlight each student’s strengths in performance while helping the students grow and mature as musicians in front of the ensemble. In addition to their time in front of the orchestras, graduate conductors serve as assistants to ESSO and Eastman Philharmonia.

Second-year MM student Garrett Wellenstein leads the Vaughan Williams, a piece scored for strings alone but divided between a solo quartet, a nonet of strings set apart from the ensemble, and the larger remaining contingent of the string section. Each group contributes its own unique color to the overall texture, and the sound goes from wispy and delicate to full-bodied and ecstatic over the course of the piece.

First-year MM student Samuel Pang will lead the Prokofiev, a work excerpted from his score to the 1934 film Lieutenant Kijé. One of the most widely-performed of Prokofiev’s works, the score features dazzling splashes of orchestral color, particularly in the “Troika” movement, and also features the solo timbres of a tenor saxophone and a double bass, used to moving effect in the lushly-scored “Romance,” as well as a cornet solo, marked “in the distance,” which begins and ends the piece. Its sumptuous melodies and vibrant orchestral textures have added to the work’s enduring popularity, and its hummable tunes will linger with audience members long after the concert has ended.

Program notes for Saturday’s ESSO concert:

Costume design from an early production of Prince Igor

Alexander Borodin: Overture to Prince Igor

Borodin was the illegitimate son of a minor Russian prince, and was well educated by his mother. He trained as a doctor and chemist and even founded a medical school for women, which he considered his greatest achievement, but posterity remembers him as a composer. His greatest musical achievement is his opera Prince Igor, which he worked on for 18 years, from 1869 until his death in 1887.

Borodin played the Prince Igor overture on the piano for his friends Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Glazunov, but by the time of his death the overture had yet to be orchestrated. After Borodin’s death, it was reported that Glazunov took to completing its orchestration from memory. Glazunov utilized his rare gift of eidetic memory and the overture, as recorded by Glazunov, is Borodin’s to the note.

The overture is a neat sonata-allegro movement that begins with a slow introduction in the strings and winds. It is interrupted with glorious fanfares in the brass, leading to a bold Russian theme. Mammalian vitality and yearning are the underlying compulsions. Three easily discernable melodies appear throughout the exposition: a quasi-oriental melody first played by the clarinet; a ceremonious melody realized by the full orchestra; and a lyrical horn solo. A fragmented but substantial development leads to a recapitulation of all the earlier themes and then a coda, rounding out one of the small masterpieces of 19th-century music.

Andrew Psarris

An artist’s impression of Thomas Tallis (or “Tallys”), produced nearly a century after his death

Vaughan Williams – Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis (1909)

In a period of worldwide artistic nationalism, British composers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries indeed sought to recapture the glory of their musical past. Vaughan Williams, given the task of editing the expansive English Hymnal in 1906, became exposed to the music of the famous English Renaissance composer, Thomas Tallis (c. 1505-1585). Inspired by a particular modal melody that Tallis wrote for the Psalter of 1567 for the Archbishop of Canterbury, Matthew Parker, Vaughan Williams composed the single-movement Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis. The work was premiered on September 6, 1910 at the Three Choirs Festival in Gloucester, England.

The form of a fantasia is characterized by the development and variation of a theme, but free of the clichéd “theme and variations” structure. Holding true to this framework, Vaughan Williams juxtaposes the original Tallis tune—somber and exotic to the ear due to its Phyrgian mode—with his original themes that derive from fragments of the original theme. The main tune, once sung to the words of “When rising from the bed of death”, appears unassumingly in the lower strings beneath an ethereal upper string trembling. The theme is transformed through the textures of the ensemble, and is repeated at full volume across the full string orchestra in a soaring gesture. A secondary melody is first stated by solo viola, transformed by the solo violins and cello, and spun out by the entire orchestra, fluidly combining with the original Tallis tune and building to a passionate and inspirational climax.

The fantasia is scored for three string ensembles set apart from one another: a full-sized string orchestra, a smaller orchestra containing a single desk for each section and a string quartet. The instrumentation and distinct spacing suggests the antiphonal character of sixteenth-century church music. The three distinct groups of performers create an enchanting effect: the quartet offers a modal, monastic chant, ritualistically supported by an orchestral congregation. Then, the sound of the smaller orchestra echoes that of the larger to create a glowing spatial effect.

John Fatuzzo

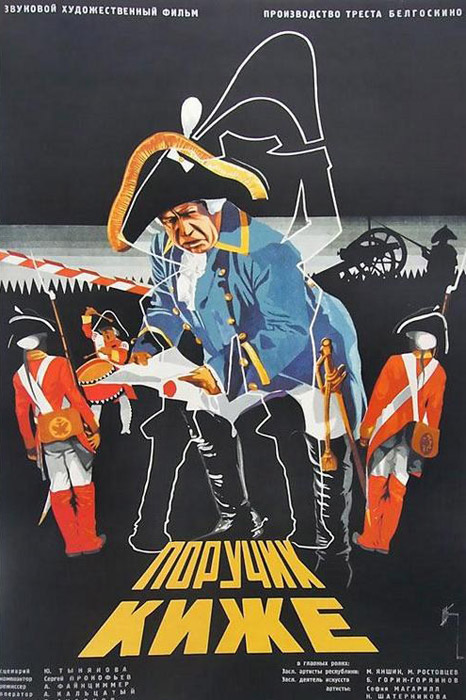

Poster from the original release of Lieutenant Kije (1934)

Prokofiev: Lieutenant Kijé, Symphonic Suite, Op. 60

In 1932, several years before his permanent return to the Soviet Union, Prokofiev was asked to write his first film score, for an adaptation of Lieutenant Kijé (or, in a spelling closer to the Russian, Kizhe), a satirical short story, well known to Russians, by Yury Tynianov (1894-1943).

In the 1940s Prokofiev would write two of the most imposing of all film scores, for Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible. His first film score was a much lighter affair; the original soundtrack consisted of 16 short pieces. When Moscow Radio commissioned Prokofiev to write a suite based on the film music, he gave it a thorough rewrite and reorchestration. The result has far eclipsed the original film in popularity (but you can watch Lieutenant Kijé, and more or less hear Prokofiev’s original score, on YouTube).

Lieutenant Kijé is, in the words of Prokofiev’s biographer Harlow Robinson, “a witty attack on official stupidity and the profoundly Russian terror of displeasing one’s superior.” The fictitious Kijé is born when a clerk repeats two letters (in Russian, “zh” and “e”) in writing a list of soldier’s names. When the (definitely not fictitious) Tsar Paul I reads the list, he demands to know more about the soldier with the unusual name. Not daring to tell the Tsar he is in error, clerks and courtiers, soldiers and clergy invent an entire life cycle for Kijé, from his rise in the military ranks, his disgrace and return to favor, his marriage … and, inevitably, his death and pompous military funeral (with an empty coffin).

Prokofiev was initially reluctant to write Lieutenant Kijé, but after realizing that its whimsy, slapstick, and even its 1800 military setting suited him to a T, said “I have absolutely no doubts about the musical language for this film.” He also saw the less amusing implications of the story, particularly for Russians soon to experience Stalinist purges and show trials; as another composer, Dmitri Shostakovich, drily put it, “It tells how a nonexistent man becomes an existing one, and an existing one becomes nonexistent. No one is surprised by this.” So Prokofiev’s colorful, tuneful music occasionally turns a shade serious, though it is never solemn.

The five movements of the suite neatly delineate Kijé’s rise and fall. The Birth of Kijé is heralded by a trumpet solo over a very quiet snare drum roll. The balance of the movement, starting with a jaunty piccolo tune, evokes Kijé’s military exploits. The Romance offers the double bass a rare chance to play a sentimental, slightly lugubrious, solo. A few minutes of romance lead to Kijé’s Wedding, a lively polka, followed by an even livelier Troika, a musical sleigh ride complete with sleighbells and (thanks to pizzicato strings and piano) balalaikas, based on an 18th-century Russian drinking song (also appropriated by Sting for his song “The Russians”). For the Death and Burial of Kijé, many of the themes heard previously make a final appearance, singly or combined. Kijé’s theme finally returns on the solo trumpet, and dissolves into silence: an oddly poignant farewell to a man who never existed.

David Raymond