By Erik Elmgren

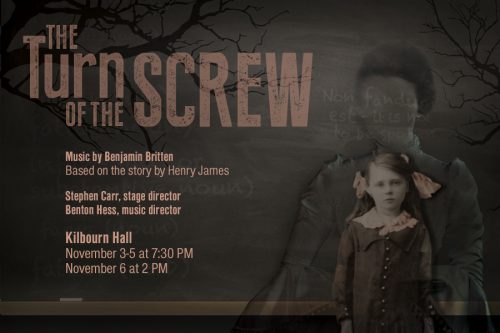

This week, the Eastman Opera Theatre will present Benjamin Britten’s The Turn of the Screw (performance dates and times are listed at the end of this post). The performances will feature two rotating casts of Eastman School of Music undergraduate and graduate students. Benton Hess, Distinguished Professor of Voice, serves as music director for the production and stage direction is by Stephen Carr, Associate Professor of Opera and Musical Theatre Studies. I had the opportunity to interview several principals in the student cast and ask them about their experience preparing to perform this show.

Yvonne Trobe is one of two students playing the Governess in The Turn of The Screw

Tell us a little bit about yourself?

Yvonne Trobe: My name is Yvonne Trobe, I’m a second year Masters degree student in Vocal Performance and Literature from the studio of Kathryn Cowdrick. I’m from Rochester; I grew up here and went to the Eastman Community Music School. I did my undergraduate degree at the Crane School of Music at SUNY Potsdam, where I studied with Donald George.

Natalie Buickians: My name is Natalie Buickians. I’m originally from Los Angeles and I am a second year DMA student in the studio of Kathryn Cowdrick. I also did my master’s degree here, and my undergrad is from Azusa Pacific University near Los Angeles.

Nick: My name is Nick Huff. I am a second year Master’s student in Voice Performance and Literature here at the Eastman School of Music.

What is your role in the opera?

Yvonne: Even though Natalie and I each play the Governess, I think we have very different interpretations of the role. One particular line I have, which I think encapsulates the character, is “innocence, you have corrupted me.” My interpretation of the character is that she is a young girl called in to be the governess of this large house and she is finally experiencing freedom in her own right. So, for the first time, she is on her own and she develops feelings for her employer (whom she has only met once), and she is in a place of trust and respect with her job. All of these intoxicating feelings come together to cause her descent into madness.

Natalie: I agree with a lot of what Yvonne just said. I think that line is really interesting because you would think that innocence isn’t corruptible. It is supposed to represent everything that is virtuous and wonderful, and so this line comes across as very paradoxical. I think this is her realizing that she doesn’t know anything about what is around her, because at the start of the show she thinks she knows what she is doing, but by the end of the show she has lost all of that confidence.

Nick: I play Peter Quint, the valet of the country estate, Bly, who died before the action of the opera begins. Whether I am real and seen as a ghost, or a fiction of the Governess’ slowly decaying mind, is a constant question in the original novel, and this ambiguity is, to a slightly lesser extent, maintained through much of the opera.

Nick Huff plays Peter Quint in The Turn of the Screw

Tell me a little bit about the opera in your own words. What makes it unique and worth performing at Eastman?

Yvonne: Well, it’s a ghost story, so it’s the perfect time to be doing it! It explores many different levels of horror, from undertones of pedophilia, manipulation, especially between adults and children and vice versa, manic depressive disorder, and other psychological conditions. The opera tells a story about things which you couldn’t talk about when it was initially written, which heightens the terror. It is never explicitly said what is happening, but instead it is told through the minds of the characters and the audience.

Natalie: I think the most important part of this opera is that every audience member walks out with a different interpretation of what happened, of what kind of horror they just witnessed. Nothing is ever explained and everything is ambiguous; everything is double-sided. We are almost dealing with parallel universes. One is represented by Quint, who is this free, liberated spirit, and then we have the Governess, who represents Victorian standards, that sort of rigid society where you can’t talk about anything and you often can’t express yourself. In the show, those two worlds collide, and what’s really wonderful is that you never know what is reality and what isn’t, so we don’t know what is in the Governess’ head and what is really happening.

Nick: This opera touches on the taboo and the otherworldly in a way few others do. With themes of sexual impropriety with children, control, death and desperation, and the idea of diminishing or corrupted innocence. As the opera progresses, it lives up to its name and simply digs in deeper and deeper until the situation falls out of control altogether. We all have to address these kinds of demons in our life. Whether it’s your first year away from school or setting out after studies with no idea what’s next, we will all be challenged to live our lives under a lot of pressure and still be basically good people – this show demonstrates that this is much easier said than done.

What is your role in the opera?

Yvonne: Even though Natalie and I each play the Governess, I think we have very different interpretations of the role. One particular line I have, which I think encapsulates the character, is “innocence, you have corrupted me.” My interpretation of the character is that she is a young girl called in to be the governess of this large house and she is finally experiencing freedom in her own right. So, for the first time, she is on her own and she develops feelings for her employer (whom she has only met once), and she is in a place of trust and respect with her job. All of these intoxicating feelings come together to cause her descent into madness.

Natalie: I agree with a lot of what Yvonne just said. I think that line is really interesting because you would think that innocence isn’t corruptible. It is supposed to represent everything that is virtuous and wonderful, and so this line comes across as very paradoxical. I think this is her realizing that she doesn’t know anything about what is around her, because at the start of the show she thinks she knows what she is doing, but by the end of the show she has lost all of that confidence.

Nick: I play Peter Quint, the valet of the country estate, Bly, who died before the action of the opera begins. Whether I am real and seen as a ghost, or a fiction of the Governess’ slowly decaying mind, is a constant question in the original novel, and this ambiguity is, to a slightly lesser extent, maintained through much of the opera.

What has the rehearsal process been like while preparing for this opera?

Natalie: This is the fastest opera I’ve ever put together. The first two weeks consisted of music coachings with Benton Hess. That in itself was very difficult, because it was the first time we all tried to put our parts together and the music by Britten is very difficult. At the end of that we had a memorized sing-through with both casts. Then we started the staging process. Working with Stephen Carr is great, because he works very quickly and he has a very clear outline of where everyone moves at first. Once everyone has rehearsed where to move and what to be singing at those points, we start working on the characters and putting intention behind each word. The week of we put it with the costumes and set and then run it a couple times before the show.

Yvonne: I think a lot of us would agree that because this music requires such detail, and we have prepared it at such a pace, that it has made us all better musicians. It really forces to use everything we have learned from all of our music education: it has solo work, ensemble work, musicianship, aural skills, and so many other things. I almost feel like I’ve had to learn every one else’s part in order to successfully perform my own. The more we work on it, the more I feel like I unlock little secrets in the score, that I’m sure our audience won’t catch on a first listen, but if they come back once or twice or even three times they might hear some of those things like musical themes or a particular Latin text.

Nick: It has been quite a bit of fun! This opera, as dark and foreboding as it is, has a lot to offer a performer. For instance we all portray British characters and, as such, need to do a fairly proficient accent, which was fun to apply to all the notes as a diction challenge. It’s quite a challenging piece, in terms of the music; it has a unique and progressive harmonic language to navigate as well as really wickedly difficult counting in some moments, but it is very satisfying to prepare. I think a lot of the cast feel a lot of pride at conquering this thing!

What is your favorite part about performing in this opera?

Yvonne: I love Quint’s music. It’s not overly lush or dramatic, but there’s something about the melismas that just draws you in. Every time Quint sings, I find myself needing to listen. It’s so interesting, almost spell-like in a way, which makes you come closer, even though perhaps you shouldn’t. I also really enjoy how different each cast is. People should come more than one time because each cast performs the opera in a very different way, both musically and with regards to interpretation. Especially since the opera is already so ambiguous from the audience perspective, that if you see it on different nights you will come away with a different perspective on the story, or maybe a completely different story altogether.

Natalie: It’s a very different experience for me when I listen to it versus when I perform it. I find that when I watch the other cast performs, there are certain scenes that I feel much more intensely than when I am performing it. I hope that soon those two different feelings will unite a bit more. I also really enjoy delving into the insanity of the character; it takes you to a really interesting mental place, especially when exploring that in rehearsal.

Nick: Tenors get a lot of romantic leading man-type roles in the repertoire; it’s a bit more rare to play a pedophilic, remorseless ghost. Obviously nobody wants to identify with such an unsavory character, but in the end we are generally products of our experience and genes and it is unceasingly interesting to me that, given the right context, if I hadn’t grown up with the healthy childhood I did, or there had been some trauma in my life, say; I might have turned out as bad as Quint, anyone could have. As an actor you have to go to a deep place to find all the components of the kind of world-view Quint must possess. It’s very dark, but very telling of what it means to be good, or not good, or whether those ideas are erroneous. I think my favorite part was to sort of find the spin, so to speak, that could justify everything Quint did, or what it is implied that he has done. No bad guy thinks he’s bad.

Eastman Opera Theatre’s performances of Britten’s The Turn of the Screw are as follows:

Thursday, November 3, 2016 – 7:30 p.m.

Friday, November 4, 2016 – 7:30 p.m.

Saturday, November 5, 2016 – 7:30 p.m.

Sunday, November 6, 2016 – 2:00 p.m.

All performances take place in Kilbourn Hall at Eastman. Pre-performance talks take place one hour before in the Ray Wright Room, Main Building.