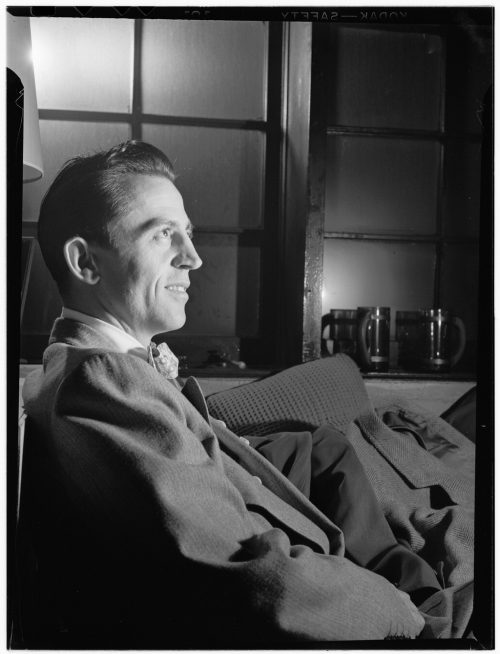

Arranger and bandleader Boyd Raeburn in the 1940s, photographed by William Gottlieb

By Dan Gross

Eastman Chamber Jazz, led by Jeff Campbell, will be playing the music of Boyd Raeburn tonight, November 8, at 8 p.m. in Kilbourn Hall. The Raeburn Band did not have much commercial success, but it played some very interesting music. There were a lot of great players in the band: Dizzy Gillespie, Shelly Manne, Britt Woodman (Ellington), Oscar Pettiford Serge Chaloff, Trummy Young, and Mel Lewis. Eastman received this music about 8 years ago, after — in Jeff Campbell’s words — an “out of the blue phone call” from a New York vocalist named David Allyn, who sang with Raeburn in the 1940s and went on to record with Bill Holman and Johnny Mandel. Dan Gross interviewed Jeff Campbell about the music on tonight’s concert, Boyd Raeburn’s career, and the road to acquiring his band’s arrangements.

The general public thinks of jazz as “niche,” but there are many jazz musicians who are household names; Dizzy Gillespie, Glenn Miller, and Benny Goodman come to mind. But who is Boyd Raeburn?

Well, he’s kind of an enigma. He was never known to be a soloist, he didn’t sing. He did play saxophone, but they always gave him a modest part, usually on the bass saxophone. He was never a real charismatic figure, he wasn’t a good-looking, handsome person that the media would have liked, but somehow he organized this band. He got a band together, and they did all this crazy music, “crazy” meaning adventurous. He had two or three key composers, one of them was this guy named Hal McKusick, one was named George Handy, who was the most adventurous of them all. They did these adventurous recordings. One was called “Boyd Meets Stravinsky,” and they had these titles like “Hep Boyds,” or “Little Foolish Boyd…”

Boyd Raeburn was married to a singer named Jenny Powell, so there was a lot of vocal music in there as well. She was a great singer.

So Duke Ellington loved this band, I think he gave Boyd thousands of dollars just to keep the band going. And a lot of people who were famous played in the band. You mentioned Dizzy Gillespie. The original version of “A Night in Tunisia” comes from the Boyd Raeburn band.

Oscar Pettiford was playing bass on that recording too, correct?

Yeah, the sheet music we have has his name for the part.

What Boyd did was adventurous, and critically beloved, but the sad side is that he went bankrupt multiple times, even though so many incredible musicians played with him. He would often go bankrupt, and then come back with a completely different lineup.

Could he just not carve out a niche because there were so many other great bandleaders during his time?

Yeah, he never really caught on, and I think so. I think probably the right combination of all the perfect storms of bad luck, that kind of thing. But he kept trying. He never composed, but he always got good composers to write for him, and he let them do whatever they wanted to. Unlike Glenn Miller, who had a very specific sound in mind, who was kind of a tyrant, and a strong leader, Boyd was loose and let the players be themselves. It was a players’ band, as far as I’ve read.

What was the usual instrumentation?

It was typical of the era in that it had four trumpets, three trombones, five saxophones – now Boyd would make the sixth sax, which was a little unusual – piano, bass, drums, and guitar. But what was unusual is that he augmented with a French horn sometimes, and used harp too.

We have two or three pieces that use harp, and we have a French horn in the band as well. If we can get our act together, we’ll have a harp for a couple.

A couple of composers combined to make the “Boyd sound.” You wouldn’t say it’s modern music – it still sounds like the 40s – but at the same time, the harmony has this post-bebop sound. Is that what kept him going?

I think so. I think that he was also kept alive because good players played in his band, and they were able to say that Boyd was a part of their legacy. I first heard of Boyd Raeburn because of Mel Lewis. He played in Boyd Raeburn’s band. I’m a Mel Lewis fan, so I knew Boyd’s name from him. I should also mention David Allyn, and that’s how we got this music. David Allyn was a very important part of the band, and they wrote arrangements specifically for him that featured his voice and his range.

Looking back, do we still feel Boyd’s influence today?

I think we do in a way, but it’s not exactly Boyd, it’s George Handy, the composer. I think because of the Stravinsky-esque attitude, we look later to people like Bob Brookmeyer, people like that who were taking the elements of adventurous and new techniques in classical music and putting them in a dance band setting. He took this swing music that was meant for dancing, we get the Ellington influence, we get the Basie thing, we get all these other bands, and even Woody Herman and the Ebony Concerto, written by Stravinsky. This band had the idea and the opportunity to take these elements of new adventurous classical compositions with harmonies that were more dissonant, and even meter changes. We have several piece where the tempo is bumping along in 4/4, and all of a sudden there are a couple measures of 5/4, just right in the middle of nowhere. That was something you’d see more in the music of Stravinsky. There are character changes in these pieces.

These are short pieces too. They’re not extended works for fifteen minutes, but they were in the confines of the big band sound. Earlier on the music was only three minutes because of the recording technology, the 78s. Some of the music goes to four, five, and six minutes. So I don’t know what was going on with the recording technology at the time, but this band wasn’t a 1935 band, like Benny Goodman.

It was a middle forties band. More around the war era, as opposed to the swing era… A little bit later.

Do we see this influence in other music? I think we do in bands like Stan Kenton’s, that kind of approach.

That’s interesting comparison between Boyd’s and Kenton’s bands. George Handy and Bill Holman respectively were the sounds of those bands, and we were doing fairly similar things.

So was it really that simple? Handy was the reason for Boyd’s success, albeit limited? You did mention that he wasn’t especially good-looking or marketable.

I think so; and the band was an interesting place to be. His son, Bruce, but I’ve never met except through emails, has been very kind to me and offering up some lost parts and support, so I look forward to asking him ore questions at some point. I myself just knew Raeburn by name, not his music.

I say he’s not good looking, because I read that, not because that’s my opinion. People said that his charisma on the bandstand was not like others, who had a magnetic personality, who would draw an audience not just because of the music, but because of themselves as an interesting person.

I’m glad you mentioned his son, because this is a legacy project of sorts. There’s a very interesting story about how you got this music.

I was sitting in my office and the phone rings. And once in a while when the phone rings you pick it up, and someone’s there. This person says “My name is David Allyn, I’m a vocalist.” I had never heard of him before, and I just listened to him. He said: “I have a large collection of music, and I’d like to donate it.” I asked for more information, and he said he sang for Raeburn.

I talked to Bill Dobbins, and I asked what he knew about the music of Boyd Raeburn. Bill said that Rayburn Wright – one of our great faculty – talked about the band and said it had great music. Bill said that if we could get the music, we should do it.

It took about sixth months of phone calls with David Allyn and myself. There was some intrigue. I still to this day don’t know what it was, but David would say that he wanted to give it to Eastman, and then he said he wouldn’t, then he would, but he would want to sell it. It was back and forth. Finally he said that he would sell it to us for several thousand dollars. I told that him that we don’t have the resources here to do that, you’ll have to find someone else. He called me back the next day, saying he’d give it to me.

So I drove to Connecticut with my daughter, who was fifteen at the time – I took her out of school for a daddy-daughter trip. David told me I needed a moving van to bring all this stuff back. I said, “What about a minivan?” He said that could work.

We said we were going to meet at the Denny’s in New Haven, Connecticut, so after six hours of driving we get there, and says, “follow me.” By the way, David was about 92 at the time. I follow through David through the cold, and we did to this palatial storage unit. I’ve never seen anything like it, it looked like a hotel. We get there, and David doesn’t have the $45 to pay the last month of rent. I pay for him, and we follow him through this labyrinth of hallways, and I’m getting more anxious as we go along. We finally get back to this door, and he can’t get the lock open.

This sounds like a Dan Brown book.

I can’t wait, and finally he gives me the combination, I bust the door open, and in this giant space are two small black boxes on a trolley. “I’ve been duped!” I think to myself. We lug this stuff out, and he says follow me. We go to that Denny’s, I buy him lunch. We sit there, and he tells me his story.

He was a young guy from New Jersey, grew in up an Italian family with an Italian name, though he changed it to “Allyn” to “Anglo-ize.” He grew up with Frank Sinatra. They were young men friends in the business, and they were buddies. Allyn joined Rabeurn’s band, and Sinatra joined Tommy Dorsey’s band…

So he says, again, “follow me. I think I have some more stuff at my house.” We go back to his apartment, and all respect to our elders, but they keep everything really warm, so we get back to his place, and it’s all hot and sweaty. He goes through all these things, and keeps pointing out boxes. So now we’re starting to find some stuff.

I look in this boxes, and here all this Boyd Raeburn music … all kinds of music. He also gave me all the band fronts; the music stands, fronts, and a box of other bandleader stuff. It was very kind.

I’m back at my place, and I start looking through this stuff, and I have piles of charts. Within these other boxes with Raeburn music, I find original penned scores of Bill Holman, and Johnny Mandel, one of a kind things. I had to sort through all this personal stuff too while getting the Raeburn charts together.

Within this stuff, there was music from Frank Sinatra too, since they were friends. There was Quincy Jones music from “Sinatra at the Sands.” We have about fifteen of those things.

David Allyn actually died two years after this. We had kept in touch that whole time, and unfortunately we couldn’t get him up here to do a clinic with that music, we couldn’t sort through it in time. There were probably about 150 charts, and some were incomplete.

We put them in the library, and Donna Iannapollo organized that stuff for us. We’ve wanted to do this concert for a while, and now the students are having a ball putting this together. There were no scores, so I had to make them!

With the big band lineup?

Yes, with the French horn and harp, hopefully as well. It’s really fun music, but some of it is really hard. This is one piece, with those Stravinsky sounds, an arrangement of “Over the Rainbow” that has meter and texture changes. It’s a Jekyll and Hyde version of “Over the Rainbow.” It just keeps changing personalities in a four-minute piece.

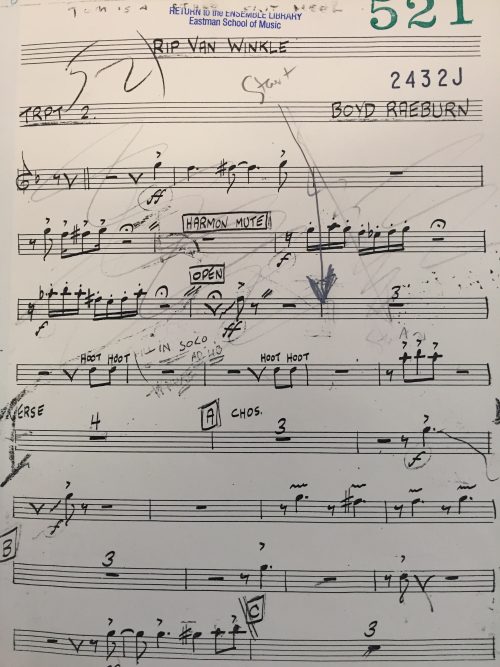

The other really fun one is “Rip Van Winkle,” originally for Jenny Powell. It’s the story of Rip Van Winkle waking up in 1943 and seeing that music was now called “swing.” It’s a fun novelty piece. It’s hard to put together, since there’s dialogue at the beginning.