By Erik Elmgren

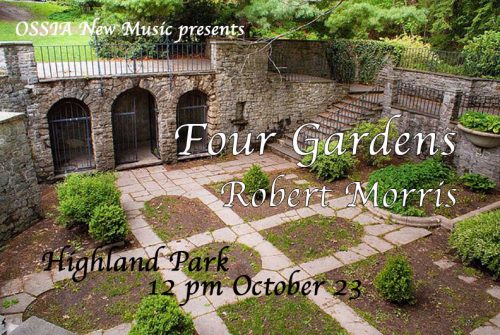

This weekend OSSIA New Music heads to Highland Park to premiere a new piece by Eastman Professor of Composition Robert Morris. The piece, entitled Four Gardens, is one of a series of pieces composed for outdoor performance and should be a unique experience for both the performers and audience. To learn a little bit more about how the piece and this collaboration between OSSIA and Eastman faculty, I spoke to the composer.

Could you tell us a little bit about the piece Four Gardens?

Four Gardens is my ninth outdoor piece. Some of these pieces are written to be performed in a specific a site—an outdoor space—usually commissions—and others can be played in different places out of doors. Four Gardens is of the latter type. Each of my outdoor pieces has a different spatial and musical idea—in this piece there are four groups of instruments placed in the four cardinal directions from each other—each has a leader, who also reads text fragments from various literatures—in this case, Japanese, old testament psalms, etc.. These texts have nature as a theme or subject. So the instrumentation is free, and the notation is adapted in each performance for their instruments in the groups.

How does the work’s unique performance space add to the piece?

The decision to play the work in Highland Park was made by members of Ossia and me together. We walked about in the city of Rochester, looking at interesting places and agreed that the top of Highland Park near the Reservoir was ideal. The four groups are situated on the edges of a circular gathering place. We like this place also because, people who are just visiting the park for fun or walking their dogs will find the piece being played as a surprising event. We hope the fall colors will be out in great array on Sunday.

This is just one of many pieces you have written to be performed outdoors. Could you talk a bit about your interest in performing pieces outside?

I have spent some time hiking in various places in the US and in Asia. The experience of being in nature–indeed being a form of nature–is very important to me. It influences all my compositions in one way or another. But the outdoor works are special because they are meant to function in the way natural events evolve and are structured. (They are also made so they can be performed with only a few hours of rehearsal (since many of them are for large ensembles)). The audience takes this music in a very different way than in the concert hall. People listen to the sound of the work attentively and don’t find the sounds dissonant or inappropriate for music—they enjoy the sounds as such. The pieces are also slow paced—the minute is the basic unit of time structure–, just as cloud formations, waves on the beach, wind and weather change—slowly and with subtle variation. I find that people enjoy these works because they can listen with an open mind and within a lovely environment. Moreover, they can come into a piece or leave it at any time since these compositions are not based on narratives, either specific or abstract.

How do you compose music meant to be performed outdoors differently from that which is presented in a concert hall?

To answer that question, here are a few passages from a little essay that I wrote in conjunction with my first outdoor piece called Playing Outside, performed by Ossia and other instrumental groups in 2001 in Webster Park.

It appears that the sounds of nature are not aesthetically arranged; they are purely functional–the outcome of what’s necessary for natural processes to continue. Bird-calls alert or attract, for instance. There are no melodies, phrases, chords in the woods, just textures and single sounds, sometimes groups of sounds. So how can my music “harmonize” with the woods sounds, rather than drown them out, or impose others? And not to imitate, either.

I take my cue from the forms in the woods, where nothing is exactly uniform or symmetrical. For instance, each leaf is different from another, even if they grow from the same branch. Processes are neither completely smooth or completely discontinuous. Each item and event–leaf, tree, path, rainfall, dispersion of seeds–is unique, its own world. And each family of thing is fuzzy: trees, bushes, vines intertwine–it’s hard to tell them apart. In other words, figure and ground are not of opposite poles, there’s camouflage too.

The rhythm of outdoors is usually slower than the social rhythms of music in cultural settings, but sometimes faster too, as with birds and insects. It is a relaxed rhythm with beginnings and endings not clearly defined, often overlapping. Sound and silence share the sonic space.

So this music has no “themes” or “accompaniments”, no clearly articulated voices, no sections, nothing exactly repeated. Its form is flow. Not the fixed forms or formulas of some traditional music, but formation and transformation, multiple processes of growth and decay, continuously developing, not without points of repose or abrupt change. Flux again and again.

Sunday, October 23, 2016 – Noon

Highland Park Overlook

450 Highland Ave, Rochester, NY

In case of rain the work will be performed inside in Annex 902 at ESM