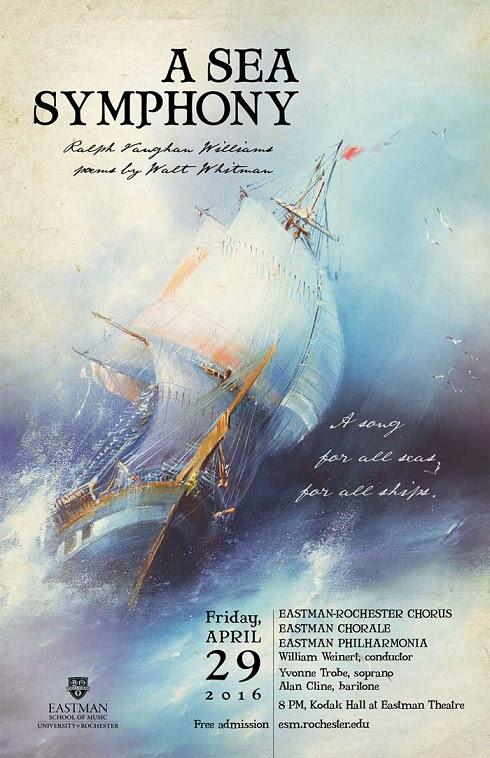

This Friday, April 29 at 8 p.m. in Kodak Hall at Eastman Theatre, the Eastman-Rochester Chorus, Eastman Chorale, and Eastman Philharmonia, all under the school’s Director of Choral Activities, William Weinert, with baritone Alan Cline and soprano Yvonne Trobe, present one of the great works for chorus and orchestra: Ralph Vaughan Williams’s A Sea Symphony. The following essay on the work appears in the program for the concert.

By Andrew Psarris

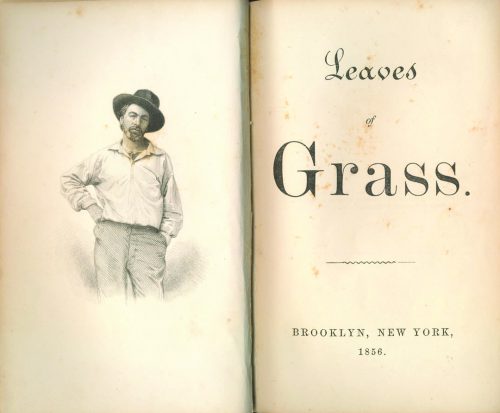

The first edition of Leaves of Grass, with a portrait of Walt Whitman as frontispiece

Let us begin where Vaughan Williams began — with Whitman’s celebrated poetry collection Leaves of Grass. Walt Whitman had a uniquely American, sometimes controversial, and often revered perspective on life. Perhaps more than any other visionary writer of mid-19th-century America, Whitman had a deep faith in democracy, and an unusual knack for recognizing its virtue in the common people. Leaves of Grass accomplishes three tasks: exploration and celebration of individuality, and personality; a eulogy for a budding nation; and poetic expression of thoughts on life’s great enduring mysteries: life, death, and rebirth. It was the second of these three points that drew Vaughan Williams’ magnificent musical representation. No one knows why Vaughan Williams chose Whitman’s poetry for his oceanic setting, but Ursula Vaughan Williams, in her biography of her masterly husband, wrote:

“…Whitman challenged English attention as a crusader, a rebel against the status quo, who furnished to a few ardent minds a means for both social and personal improvement. It was as a moralist and a prophet rather than as an artist that he threw the gauntlet to the English, and English recruits marched to its banner because they found in Leaves of Grass disturbing intimations of a new social dispensation, a renovated humanity, deriving its vitality from the transcendent personal magnetism that the poet was said to exemplify in his own life.”

Whitman, the champion of American individuality, aided the liberation of England from the influence of European literature. Vaughan Williams, similarly attuned to his own beloved nation’s mores, sought to free English music from the grip of the continental Austro-German framework. Vaughan Williams, like Whitman, drew inspiration from the auspicious vision of a world adrift in a sea of humanistic inspired vanity. This long-awaited renaissance drew from the ashes of British music one of its greatest works — A Sea Symphony, Vaughan Williams’s first symphony.

Although the Sea Symphony is one of the greatest pieces of the early twentieth century, Ralph Vaughan Williams was at first an unremarkable musician. He was not blessed with the natural talent of Mozart or Mendelssohn, or even that of Holst or Britten; his success was a product of single-minded determination. He was an unsuccessful practitioner of the violin and piano, though he showed an aptitude for composition. Vaughan Williams’ musical interest was a consequence of his upbringing in a well-to-do, intellectual family that included the likes of Charles Darwin. (Indeed, one of Vaughan Williams’ earliest memories was of his mother’s answer to his question about Darwin’s controversial On the Origin of Species: “The Bible says God made the world in six days. Great Uncle Charles thinks it took longer, but we need not worry about it, for it is equally wonderful either way.”) Music was important to the family and to the young Vaughan Williams, but it wasn’t his only interest. He was a passionate reader of Shakespeare, and he loved architecture.

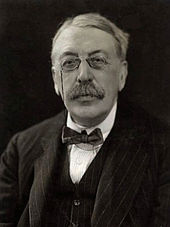

Vaughan Williams’s teachers Sir Hubert Parry (top) and Sir Charles Stanford

He was descended from great lawyers and eminent judges, but to his family’s dismay, he went into music—a career for which they thought him ill-suited. At the Royal College of Music he studied with Charles Villiers Stanford and Hubert Parry, who introduced him to the great British choral tradition. In 1892, Ralph went to Trinity College, Cambridge, to study both music and history. At Trinity he studied with the eminent church musician Charles Wood. From Parry he learned about the choral tradition; from Wood he developed his penchant for church music. Vaughan Williams showed no wish to follow in the footsteps of his teacher Stanford’s idols, Brahms and Wagner. He let Stanford know this in no uncertain terms, but beneath the guided façade of Stanford’s hardheadedness lay a recognition of talent in the young composer.

Soon after the turn of the century, Vaughan Williams begun to establish a name for himself as a composer of tuneful songs; then two things happened to him that, in the words of Michael Kennedy, set him on a path towards history. He accepted an invitation to edit the music for a new English Hymnal, and began his tireless collection of traditional English folk songs. The stage was set for his greatest works.

Dr. Ralph Vaughan Williams – The English Composer, Conductor and Organist, b.Gloucestershire 1872, d. London 1958 credit: ArenaPAL

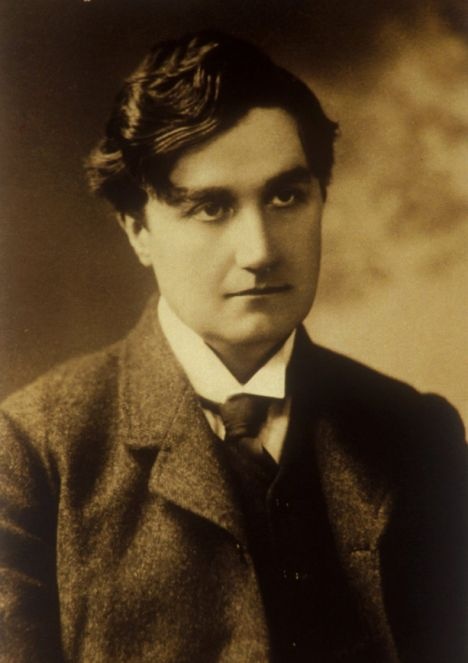

Vaughan Williams in about 1910, the year of A Sea Symphony’s premiere

A Sea Symphony premiered at the Leeds Festival on October 12, 1910, under the baton of Vaughan Williams himself. Its gestation took nearly six years. A Sea Symphony is a monumental work, with bold sweeping orchestral gestures amidst a sea of vocal waves. It defies precedent; with its masterly handling of the English- inspired melodies interspersed with sonorous moments of orchestral color, it takes its seat in the hall of the great pieces as a clarion voice of the resurgence of British music.

The chorus’s opening bars in A Sea Symphony

A gleaming yet foreboding fanfare in the brass leads inexorably to the chorus’s shout of “Behold!” fortissimo in B-flat minor. And then, with the addition of timpani and organ pedals, “the sea itself” is sung on a five-and-a-half octave D-major chord—the tonic. “The opening two chords produced an almost visual effect upon the hearers as though a curtain were drawn back and the expanse of the sea revealed,” in the words of an anonymous contemporary reviewer for the New York Times. This two- chord motif (I-bVI) occurs throughout the four movements

The first movement, “A Song for All Seas, All Ships,” comes from a poem by the same name and in part from a poem entitled “Song of the Exposition” from Whitman’s thirteenth book of the Leaves of Grass. The text is a rhapsody for the sea and for all those “Pick’d sparingly without noise by thee old ocean, chosen by thee…” The baritone enters declamatorily celebrating the ships, their waves spreading, spreading as far as the eye can see—in contrast to what Whitman calls, in his text, “a rude brief recitative.” The pretense is broken on the word “surge,” revealing the clash of a C# augmented chord. Vaughan Williams continues to use the baritone to describe the nobility of the great sea captains, but he drops the orchestra completely, casting the chorus in a four-part eulogy for those few “…taciturn, whom fate can never surprise nor death dismay.”

The opening fanfare interrupts again before the soprano entrance, “Flaunt out, O Sea, your separate flags of nations!” Two of Whitman’s lines—“But do you reserve especially for yourself and for the soul of man one flag above all the rest/A spiritual woven signal for all nations, emblem of man elate above death”—are paramount. With these lines, Vaughan Williams tempers the glorious pageantry of the sea with a nod to the human soul in the midst of this expanse—the central subject of A Sea Symphony. “Token of all captains…” is the development’s highest point, begun by the soprano on a high A. The music begins to fragment, with motives circling each other, until the baritone and chorus initiates a recapitulation on “A pennant universal.” For the final climax, “one flag above the rest,” everyone on stage is playing and singing together for the first time. The ending is hushed and dark, for it comes in the key of C minor, striking a shadowy tone in the context of D major.

The second movement, “On the Beach at Night Alone,” involves a single poem of Whitman’s, Clef Poem, in stark contrast to the multiple texts used in the first movement. It opens with a dark C minor chord resolving to E major, the same relationship as the first movement’s opening gesture of B-flat minor to D major — although in an undeniably darker mood. It is scored for baritone solo and semi-chorus. The baritone leads this existential dance, contemplating, “A vast similitude interlocks all … All distances of place however wide, All distances of time…” Although the baritone leads the movement, the intimation that here are reflections too deep for words leads Vaughan Williams to put his final assurance in the orchestra. The serene postlude of this movement puts him among the greatest British composers.

The scherzo, “The Waves,” begins with a brief trumpet fanfare and a choral phrase built on two chords, the first in minor, the second in major. This bravura movement stands in direct contrast to the introverted second movement. It avoids the metaphysical, and while putting aside the robes of philosopher-king, dons the sparkling suit of a circus performer. It is an exciting pictorial of the ocean’s surface. Like the text, the music is: blithely prying, buoyant, yearning, flashing, frolicsome, fragmented, and undulating. It plays between the two keys of G minor and B-flat major before closing in G major. The setting for the last word, “following”, the composer happily admitted, is cribbed from Beethoven’s a capella choral setting of “Gloria” in his Missa Solemnis.

The finale, “The Explorers,” is the longest of the four movements. This has been the destination all along. Whitman and Vaughan Williams no longer muse on palpable images of ships, flags, and waves and the philosophical extension of their interconnectedness. They structure this deeper metaphysical vision outward from there, extending the promises of those earlier sections to the greatest vessel of all — man himself. The opening pages of the finale include another admitted crib, from Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius. As quickly as Elgar came, he goes, as the music turns modal for a darkly contemplative moment in contemplation of creation: “Wherefore unsatisfied soul? Whither O mocking life?” The poet answers with the climactic outburst: “Finally shall come the poet worthy that name,/ The true son of God shall come singing his songs.”

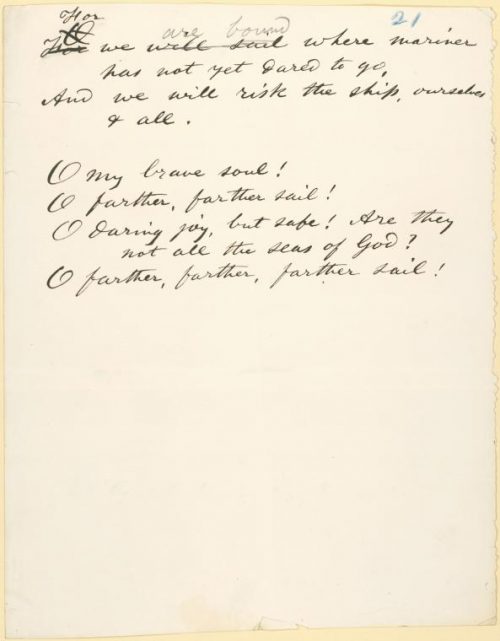

But this isn’t the end. The soprano and baritone rise up again, adjuring the soul to set sail: “Sailing these seas or on the hill, or waking in the night,/Thoughts, silent thoughts, of time and space and death, like water flowing.” The baritone sings, “Swiftly I shrivel at the thought of God.” (The composer’s use of his soloists in this ecstatic movement recalls many soprano-baritone duets – dialogues between the human soul and Christ — in the cantatas of RVW’s beloved J. S. Bach.) Vaughan Williams provides a musical answer to this chilled introspection of meeting the creator as the soul is “bidden to hoist the anchor” and to set out for “deep waters.” With the sensitivity of a far more experienced composer, Vaughan Williams does not write a monumental ending. Instead he brings about an eloquent, hushed epilogue. In a final reverent moment, the soprano adds: “O my brave soul! Oh farther, farther sail!”

Lines from A Passage to India set by Vaughan Williams, in Whitman’s handwriting

This mammoth, hour-long work is unconventional. It gives us hope: hope for a renewed identity, hope in the contemplation of things unknowable, and a reminder that time is our companion on the journey across God’s sea. What will shake us from our despondency? Vaughan Williams gives us our answer in his music; from a foreboding clef of its opening minor-key fanfare, to the hushed tones of strings receding to a place we know not where.